By Mark Simmons

It was the humid season on Malta that September of 1943. The hot Sirocco winds from North Africa blow from August to October across the cool sea, raising humidity. The local sailors do not like them because the seas have time to build up and on land they can bring bad dust storms to the Maltese islands and Sicily. However, the weather was clear on the day the Italian fleet came to surrender.

On September 11, Admiral Andrew Browne Cunningham, commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, known affectionately as ABC, was able to signal the Admiralty in London: “Be pleased to inform their Lordships that the Italian Battle Fleet now lies at anchor under the guns of the fortress of Malta.”

The people of the island rejoiced as the Italians surrendered. Malta was en fete, with the people wild with jubilation and many of the streets draped in flags. Among others, the parish priest of shattered Senglea contiguous to the dockyard and therefore one of the main targets of air attack announced the Italian surrender from his pulpit.

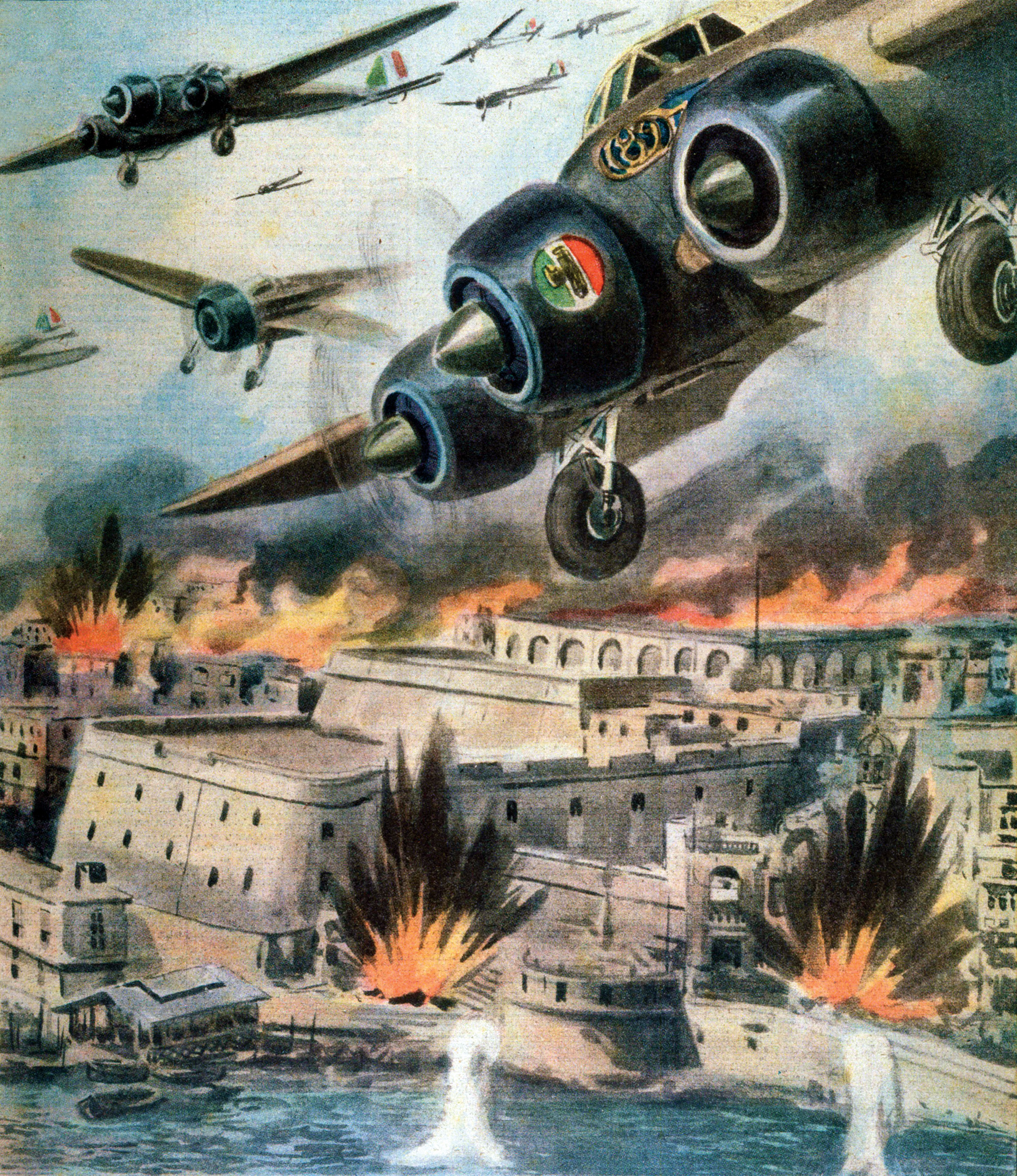

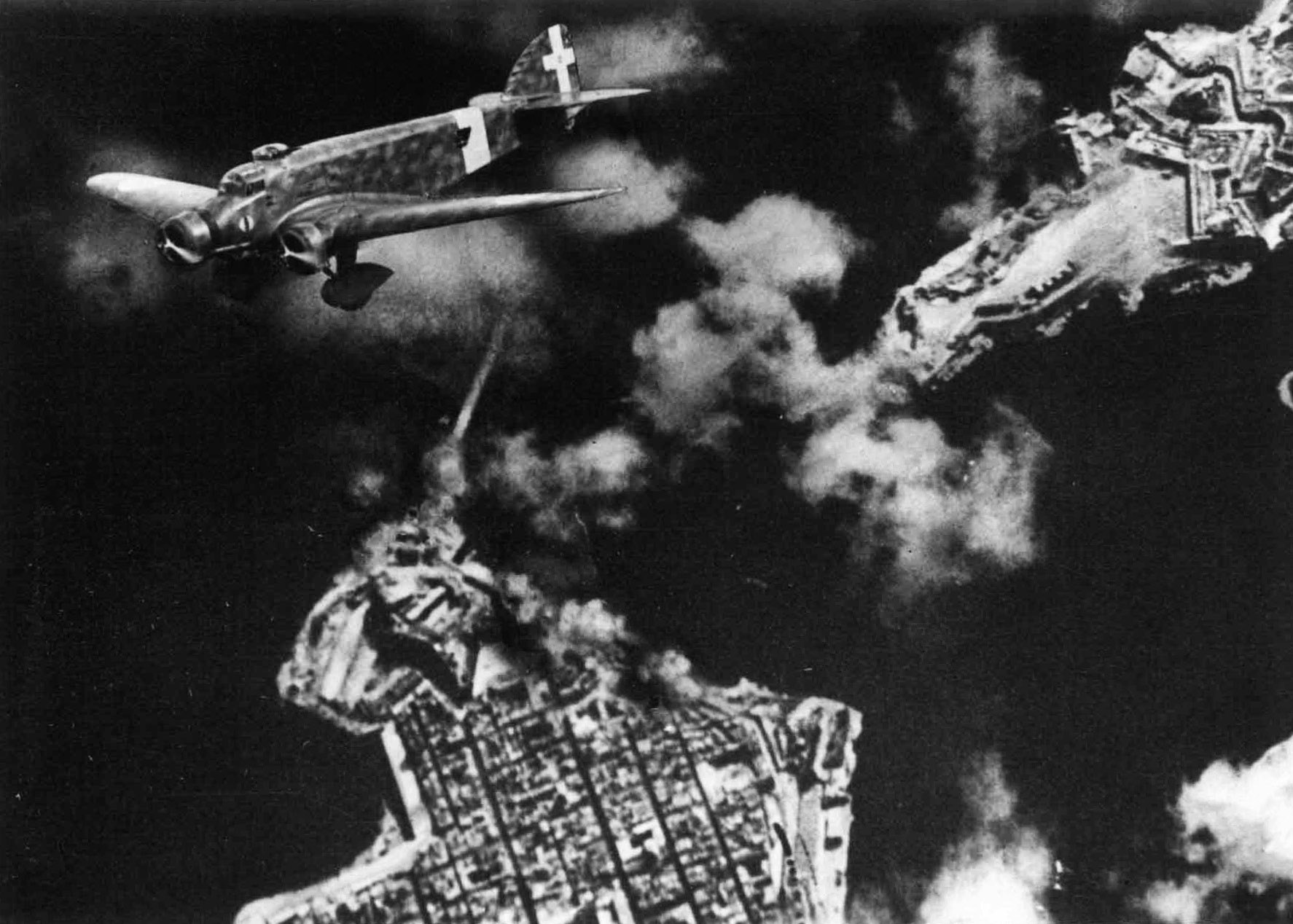

The outlook in June 1940 could hardly have been more different; on June 10 Mussolini had declared war on the side of Germany at midnight, and the first air raid on Malta by Italian bombers took place at 6:55 the next morning. Admiral Cunningham had withdrawn the heavy units of the fleet to Alexandria some time before, thus there was little to resist the air attackers who bombed at will.

Two weeks later France fell, and the whole balance of naval power in the Mediterranean changed. The western half of the sea, previously covered by the French, was laid wide open; a Royal Navy squadron, later to be named Force H, was formed at Gibraltar to cover it. The battleships of the Mediterranean Fleet, without air cover, could not operate from Malta.

The high command in London considered abandoning the island and the eastern half of the sea. In the inter-war years the island had been written off as indefensible by the British Royal Air Force and Army given the financial constraints of the time—against the protests of the Navy. However, Prime Minister Winston Churchill overruled this, ordering that Malta must be held.

So began the epic struggle to keep Malta supplied and to build up its striking power. The islands of Malta consist of Malta, Gozo, and Comino and have an area of about 100 square miles.

The Maltese archipelago has been a coveted possession through the ages as they lie right across the main sea routes of the Mediterranean, being about equal distance from Gibraltar (1,150 miles) and Alexandria (960 miles), as well as being central on the route from mainland Italy to North Africa (about 400 miles), and only 60 from Sicily. The island, according to one historian, has one of the “largest and finest of natural harbours in the Mediterranean.” In 1940 the population was around 250,000, 95 percent of which were Maltese.

Admiral Cunningham early on argued that the Mediterranean Fleet must be reinforced and seen to be active in the eastern and central areas. He soon decided to keep Malta in the fight, but he needed to deliver two convoys each month of 40,000 tons of stores, a formidable target.

On a personal note, he was glad when his wife and daughters evacuated to Alexandria from Malta: “I was delighted to get my wife and the two girls out of Malta. Bombed practically every night and often by day, they had not enjoyed it. My wife had chalked up 72 raids from the day Italy entered the war until the time she left, a period of 29 days.”

The inability of the RAF and Army to garrison Malta while there was still time was matched by the Italian failure to capture the island while they had overwhelming forces available.

Commander Marc Antonio Bragadin wrote in his History of the Italian Navy in World War II, “As for Malta, its ports and airfields were practically in the very heart of Italy’s most strategic area. In fact, since 1938 the Navy had maintained that the occupation of the island was a primary and indispensable condition for conducting any such war as the present one against Great Britain. When it first appeared possible that Italy would take part in the war, the Navy presented a plan for the conquest of Malta to the Supreme Command.

“But the Supreme Command gave up the idea because of the presupposition that the war would be a short one, and also because it was believed that the Italian Air Force would be able to neutralize the island’s military usefulness.”

So the British felt they could not hold Malta because they did not have the means to do so, while the Italians with the means to invade did not think they needed to occupy the island.

However, the British ability to make do and muddle through came to the fore. Eight crated fighter aircraft (in crates marked “Boxed Spares—Property of the Royal Navy”) were found in a hangar at the naval air station at Marsaxlokk Bay. They were obsolete Gloster Gladiator fighter biplanes, left behind by the aircraft carrier Glorious when she had left Malta for the Norwegian campaign. Four were immediately turned over to the RAF and quickly assembled; they were soon in the air fighting the Italian bombers, albeit against heavy odds.

For weeks these aircraft fought valiantly, bringing down several of the raiders for the loss of one of their number. The other three were nicknamed Faith, Hope and Charity; they soon became a symbol of Malta’s growing resistance. They were joined in July by five Hawker Hurricane fighters which had arrived, staged through France and Tunis shortly before the French collapse.

No. 830 Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm, with nine Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers originally based at Toulon to work with the French Navy, arrived and became the islands’ only offensive arm. Antiaircraft gun defenses for Malta amounted to only 34 heavy and eight light guns, with one radar set.

Mrs. Queenie Lee was on the island during the entire siege and spoke of the early days during a broadcast on June 29, 1943: “In June 1940 when Italy came into the war, no one quite knew what to expect. Our first raid was six hours after war was declared––at dawn on June 11. There was what seemed then a terrific amount of noise. I didn’t know the difference between guns and bombs, as I sat in an old boathouse under some fortifications with other women at war work. We felt comparatively safe as we’d been told it was an air raid shelter and we could sleep there.

“There was excitement in the Island that June … families seemed to think that movement was the solution to all problems. Hundreds of them packed up a few possessions and went to seek safety in the centre of the Island, and the squares near the coast and harbour were dead except for battalions of hungry cats.

“I remember going along the seafront between raids, and seeing no-one but a solitary old man sitting on the edge of a bomb crater, serene in the belief that two bombs never fall in the same place…. In a few weeks, raiders were treated with contempt and most people returned to their homes and life became normal except for the inactivity in the creeks and harbours.”

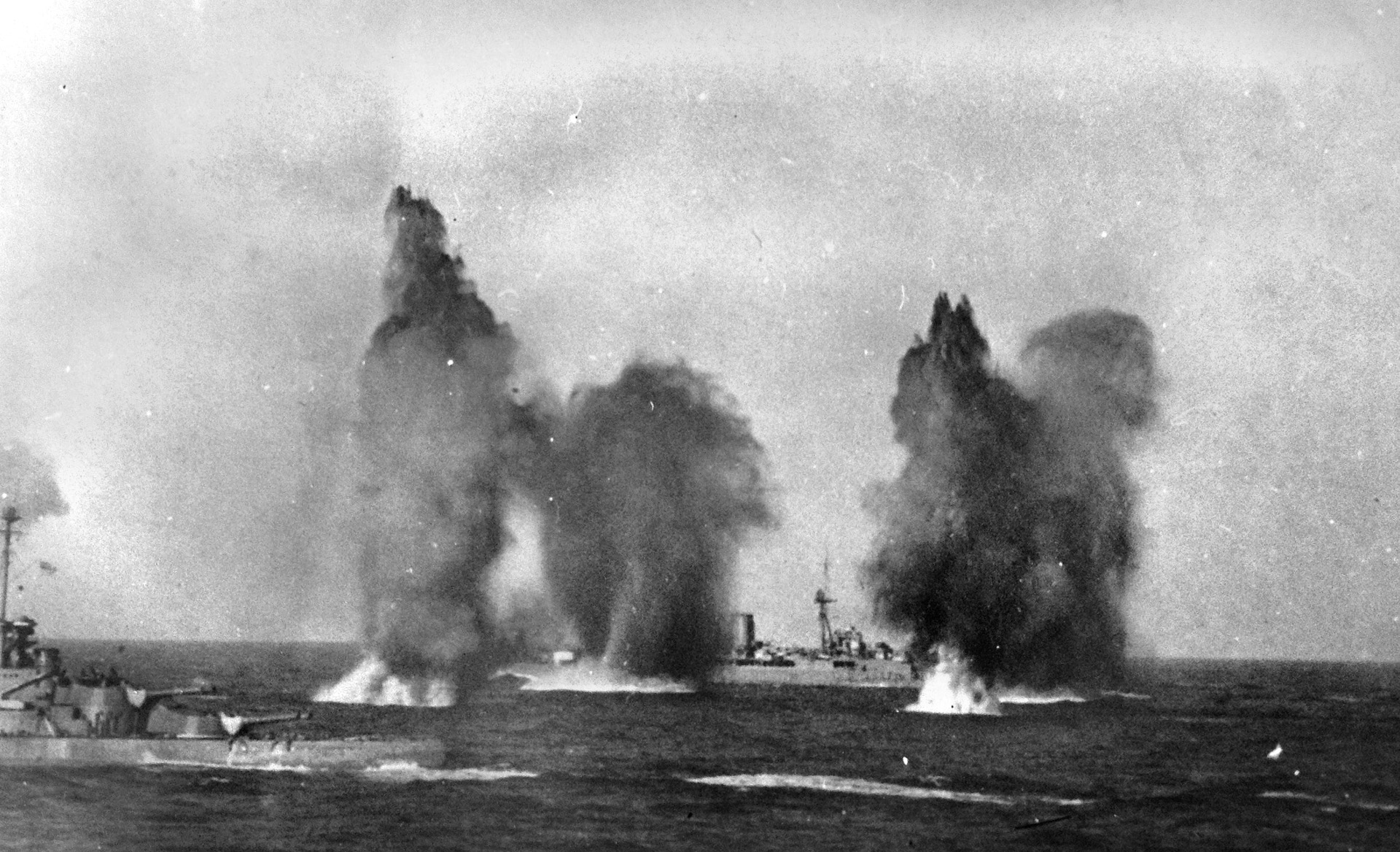

Early in July, Cunningham’s fleet put to sea to cover two convoys from Malta to Alexandria. On July 8, after 22 air attacks, observers on the flagship, the battleship HMS Warspite, counted no fewer than 300 bombs dropped around her.

Late the next day, the cruiser Gloucester of the 7th Cruiser Squadron was hit, the bomb falling on the bridge and killing the captain and 17 men. However, the Italian Air Force was unable to prevent Royal Navy operations during daylight in the central Mediterranean.

That afternoon Cunningham learned that the Italian Fleet was at sea. He hoped to bring it to action by placing his fleet between the enemy and its base; he therefore steered toward Taranto. The Italian command ordered their fleet commander, Admiral Inigo Campiani, to avoid action until the next day when the British would be within range of more Italian bombers from mainland airfields.

At 3:50 pm the next day the two fleets clashed, both sides exchanging fire; the Italian battleship Cesare was hit by a 15-inch shell from Warspite. Campiani withdrew under smoke screens. At about 4:40 Cunningham turned away, concerned about destroyer or submarine ambushes. Indeed, Campiani’s plan had been to try and lure the British across a line of submarines; however, these craft were far to the south.

By this time the British fleet was only 25 miles from the coast of Calabria. More high-level bombing attacks developed over the next four hours, during which the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force) even managed to bomb its own fleet—much to the fury of Campioni—although failing to hit any ships.

The safe arrival of the British fleet and two convoys in Alexandria brought the operation to an end. Material damage to both sides had been negligible, but what had happened clearly demonstrated the problems facing both sides, though at the time neither fully understood it.

Captain Donald Macintyre wrote, “To both it was demonstrated that a British fleet operating from Alexandria could not prevent the safe passage of Italian supply convoys to Africa. From the Italian point of view, this supported their contention that there was nothing to be gained from sending their battle fleet out to seek action as an end in itself.

“What the Italians failed to see was that this situation must sooner or later force the British to strain every nerve to restore Malta … as an air and naval base from which to attack their convoys to Libya. The only certain way to prevent this was by capturing it while it yet lay virtually defenceless…. But both the Italian and German Supreme Commands believed they could achieve their object merely by neutralising the island by air attack. It was to prove a fatal mistake.”

The lack of British fighter aircraft on Malta had become critical, so in August the old carrier Argus, operating with Force H from Gibraltar, flew in 12 Hurricanes from a position south of Sardinia in Operation Hurry. In November Argus flew in 12 more in Operation White; however, due to navigational problems, only four of these arrived.

On Malta a general call-up had taken place and a Home Guard formed. Both the island’s regiments—the Royal Malta Artillery and the King’s Own Malta Regiment—had been expanded. Steps were taken to prevent hoarding food. Stray cats and dogs were destroyed. Agriculture was stimulated, and even the precious golf courses and polo grounds were dug up to produce crops.

The air raids continued; there were more than 200 in 1940. Fortunately, military and civilian casualties were few. Social life continued with dances at clubs. The popular cinemas remained open, although electricity was restricted to the projection rooms, the public having to grope their way in and out. Bars remained popular, although prices rose as stocks dwindled.

On October 28, Italy invaded Greece unprovoked. By November 6, Count Galeazzo Ciano, Benito Mussolini’s son-in-law, wrote in his diary that the unexpected counterattack “by the Greeks is slowing down and they had no reserves.” On November 12 he wrote, “A black day. The British have attacked the Italian Fleet at anchor in Taranto.”

Swordfish torpedo bombers from the carrier Illustrious had struck the Italian Fleet at its base at Taranto in a night raid. Out of five serviceable battleships, three had been severely damaged, and the Cavour beached after being hit and was never to be seaworthy again.

While General Archibald Wavell’s desert army pushed the Italians back to the Libyan border in the Western Desert, Admiral Cunningham, after covering another convoy, sailed his fleet back to Malta, taking the flagship Warspite into Grand Harbour on December 20.

“As we moved in with our band playing and guard paraded,” Wavell wrote, “the Barracas and other points of vantage were black with wildly cheering Maltese. Our reception was touchingly overwhelming. It was good to know that they realised that though the fleet could not use Malta for the time being, we had them well in mind.”

The next day Wavell went to the dockyard where he “was mobbed by crowds of excited workmen,” and “I had difficulty in preventing myself from being carried around, and had to make more than a dozen impromptu speeches telling all and sundry how greatly the fleet depended on them.”

Ominous movements, however, were beginning to take place that would test Maltese and British resolve to keep the island in the war during the coming year. Germany was coming to the aid of her Italian ally. In December orders were issued for Fliegerkorps X from Norway, a unit that had specialized in attacks on shipping, to move to airfields in southern Italy. By mid-January 1941, 186 aircraft of all types were established on Sicilian airfields. Their first priority was to attack British shipping, with the carrier Illustrious high on the list of targets. Next was to neutralize Malta.

However, the RAF struck first when Vickers Wellington bombers of No. 148 Squadron from Malta bombed the Italian harbors of Brindisi, Bari, and Taranto where supplies for the Axis armies in Greece were shipped. Naples, where the Italian Navy was now concentrated, was also hit; the cruiser Pola and battleship Cesare were damaged, which resulted in the capital ships being moved north to Genoa. Thus, for the time being, the operations of both British fleets were relieved of the threat from large Italian surface ships.

On January 10 the entire Mediterranean Fleet was at sea to take over escorting an eastbound convoy from Gibraltar, a maneuver called Operation Excess. Force H took the convoy as far as the Sicilian narrows, where Italian aircraft bombed the convoy with no success, losing two aircraft to the carrier Ark Royal’s Fairey Fulmar fighters.

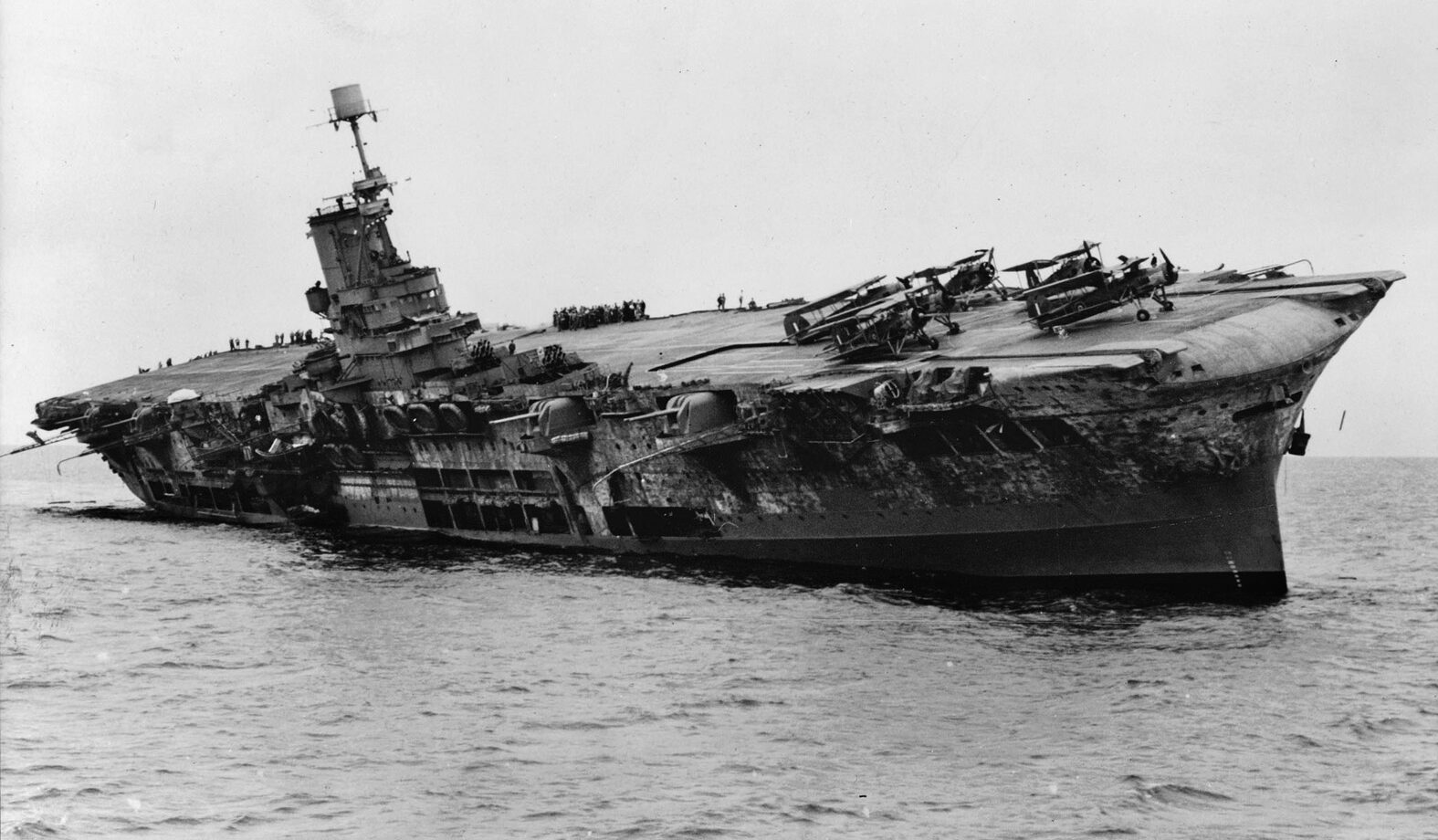

As the convoy neared Malta with its close escort, Cunningham’s fleet took over with the battleships Warspite and Valiant and the carrier Illustrious. At about 1 pm a host of aircraft was seen gathering. These were Junkers Ju-87 (Stuka) dive bombers followed by Ju-88 bombers. Illustrious flew off more fighters to join the standing patrol, but they needed time to gain altitude. The Stukas attacked first, concentrating on Illustrious. In precision attacks they hit the carrier six times, sank a cruiser, and damaged another.

Stoker Albert Jones of Illustrious recalled, “Things then began to happen so fast and changed to near chaos as the Germans began to score hits on us. With each successive explosion and the gunfire up top, a horrendous cacophony could be heard…. Suddenly there was a tremendous explosion and the ship shuddered from stem to stern under the impact, as if some unknown force had struck us with a gigantic sledgehammer.”

By 1:30, Illustrious was severely damaged. Bombs had wrecked the flight deck, destroyed nine aircraft, put half her guns out of action, and set the ship afire fore and aft. For three hours the crew struggled to regain control; the steering gear was disabled and the ship turned in circles. Control was finally regained using the engines to steer.

With great difficulty the carrier was nursed into Grand Harbour and berthed at Parlatorio wharf in French Creek. When she was damaged, 12 of her Fulmar fighters were in the air; these had flown to Malta, refueled and rearmed, and were in the air again to cover the ship.

Malta struck back on the night of January 12, 1941. RAF Wellingtons bombed the Luftwaffe airfields at Catania in Sicily. Buildings were hit and 30 aircraft destroyed on the ground.

On January 16 the first attacks by Fliegerkorps X began on the harbors of Malta and on Illustrious, as her crew and the dockyard workers struggled to make her ready for sea. The carrier was hit again but suffered only minor damage. The same could not be said for the surrounding area.

Civilian Joseph Caruana watched the plight of Illustrious: “The aircraft carrier was across the creek from Senglea, and my town was well within the target area. The noise and commotion was fantastic and my memories are a kaleidoscope of terror. The whining war cry of the diving Stukas, the loud and incessant firing of the AA guns; the terrifying shaking of the ground and house with each explosion….

“After the raid I remember people staring, dazed and awed, at the destruction while others worked with frantic haste to rescue people buried under the demolished houses … while that area of the town abreast the moorings of Illustrious was pulverised into a carpet of rubble. Illustrious was still afloat and apparently undamaged.”

Kathleen Norman, a naval wife, recorded the scenes around and on board Illustrious: “Each day, as we came in at the gate, there was some fresh scene of devastation. Workshops lay piled in rubble and glass. Iron girders were twisted and torn…. [The crew] had lost most of their gear. They were dressed in old boiler overalls, in grey flannel trousers and sweaters—any old garment they had managed to rescue from the wrecks of their cabins. The surgeon of the ship had done wonderful work in the battle at sea. He was pale, and his face was very, very, sad.”

Surgeon-Commander John J. Keevil was awarded the DSO for his work on Illustrious and ashore on Malta. Mrs. Norman went on board the battered carrier: “It was the first time I had ever been on board a wounded ship. When I saw Illustrious’s great torn decks, the aching chasm that reached into her bowels, the little sickbay that had known such horror, I felt almost as near to tears as when I talked with her tired seamen.”

Three days later the attack was renewed by swarms of Stukas and fighters. They concentrated on Malta’s airfields at Hal Far and Luqa; six aircraft were destroyed on the ground and many damaged. Illustrious, it was hoped, would sail on the 20th, but heavy attacks on the 19th in the dockyard areas resulted in underwater damage to her keel plating, requiring further repairs. Finally the Vice Admiral at Malta, Sir Wilbraham Ford, was able to report the carrier ready for sea on the evening of January 23.

At dusk that day, Illustrious crept out of the harbor unobserved by the enemy. At Suda Bay, destroyers and cruisers had been assembled to cover her passage. Two merchant ships left just before her to take advantage of this cover as well. That night she ran up to 24 knots. The cruisers and destroyers missed her, not expecting such a turn of speed from the patched-up vessel. They came under attack by enemy aircraft but suffered no heavy damage. Illustrious escaped unscathed, helped by poor visibility. At noon on the 25th, Illustrious steamed into Alexandria harbor, to be cheered by every ship there.

Admiral Cunningham noted, “I sent a message to the Vice-Admiral at Malta expressing our warmest appreciation of the work done under conditions of great difficulty to get the ship away. The men of Malta dockyard deserved all the praise we could give them.”

After the departure of Illustrious from Malta, Fliegerkorps X’s first onslaught on the island abated. Hitler’s directive No. 22 to the air fleet said to attack British naval forces in the eastern and western Mediterranean to protect Axis transports crossing to Africa and to attack British forces in Cyrenaica. Erwin Rommel, by February 1941, was ashore in Africa and demanding more air units transferred to support his troops.

The Germans first had to neutralize Malta. The strength of Fliegerkorps X had increased from 243 aircraft in February to a peak of 443 at the end of March; however, it suffered heavy losses and could not fulfil all its tasks.

In January 1941, there had been 58 air raids on Malta, with bombers concentrating on warships and dockyards. No. 2 drydock was badly damaged, and No. 3 drydock was also damaged, as was the destroyer Imperial, in it at the time. Unexploded bombs were widespread and had to be dealt with; a wide range of storage facilities were also damaged.

In February, the Germans changed tactics. Instead of daylight raids, they hit the island every night with up to 45 bombers. On moonlit nights, the airfields at Luqa and Hal Far came in for particular attention. On February 12, Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters started daylight sweeps with the object of destroying Malta’s fighter force while bombers began dropping mines in the harbors.

Toward the end of the month, bombers returned to daylight raids, destroying six Wellingtons on the ground. After heavy raids on March 5 and 7, Air Vice Marshal Forster Maynard advised that the Sunderland flying boats and Wellingtons should leave; both squadrons departed for Egypt during the month.

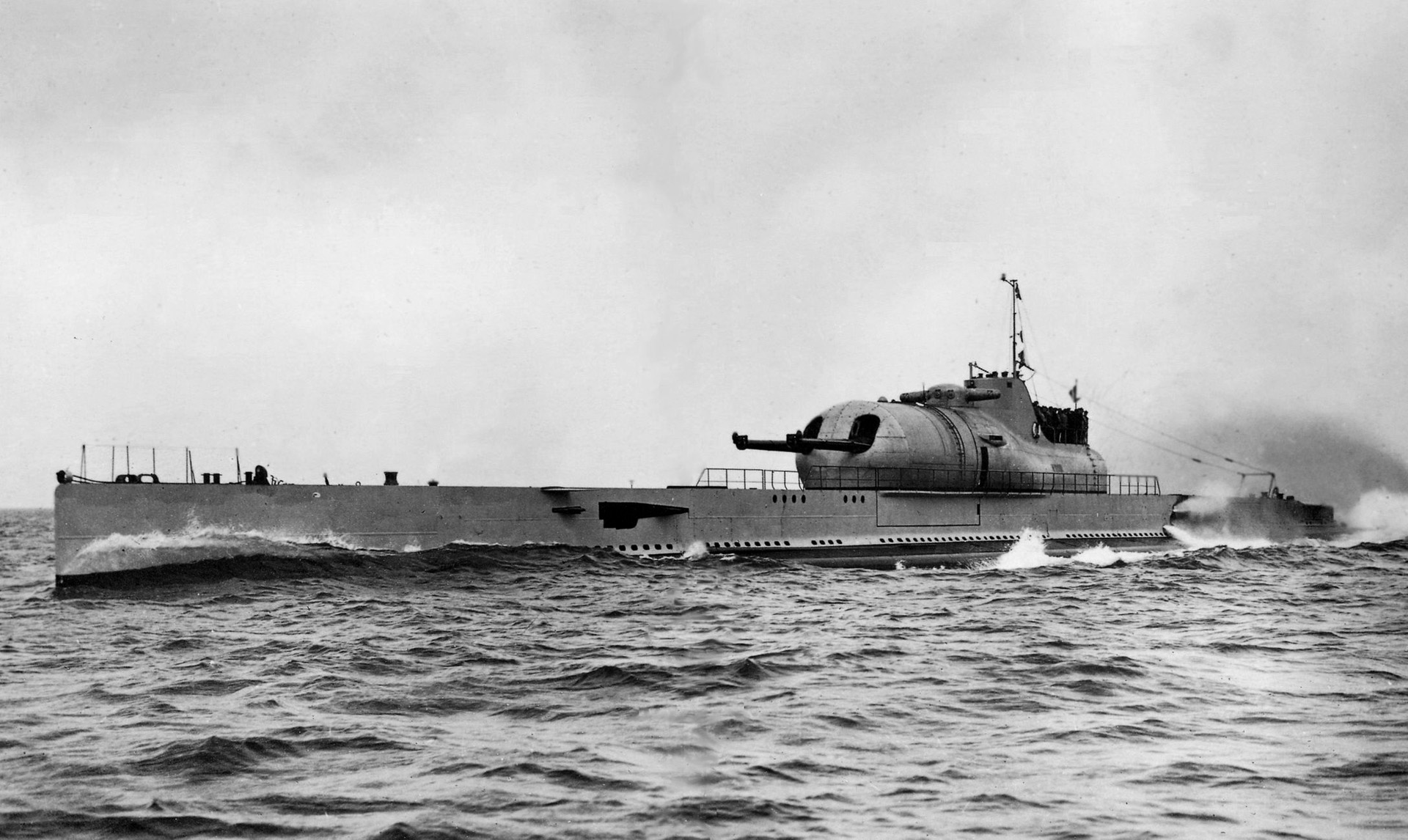

However, the island’s submarine force was by this time hitting the Axis convoys to Africa. On average, three or four submarines were on patrol at any one time, and 16 successful attacks were made in January through April, while the Swordfish of No. 830 Squadron sank two ships.

Force K arrived at Malta in April to join the striking forces, consisting of the 14th Destroyer Flotilla supported by the cruiser Gloucester. On arrival the ships refueled and went out after an Axis convoy but missed it. The next day a southbound convoy was located, but again the flotilla failed to intercept it and was bombed on the return in the Comino Channel between Malta and Gozo.

However, on April 15, they did catch a convoy and sank five heavily laden transports and their escort of three Italian destroyers, for the loss of the destroyer Mohawk.

Fighter aircraft reinforcements also were beginning to arrive through a series of operations; 600 new fighters were delivered in less than two years by aircraft carriers. On April 3, 12 Hurricanes were delivered by Argus with Ark Royal supporting.

Ark Royal was well known to the Maltese before the war; she would help deliver 327 fighters to the island until her loss in November 1941, when she was torpedoed by a German U-boat east of Gibraltar on the return from one of these ferrying operations.

In March 1941, the Mediterranean Fleet scored a notable one-sided victory over the Italian Fleet at Matapan. Ultra decodes of Enigma signals between the Italian Fleet and the Luftwaffe gave Admiral Cunningham a marked advantage in the battle, which he exploited to the full, the first use in action of the famous Enigma decodes.

However, it was imperative that this advantage was not discovered by the enemy. Thus a Sunderland flying boat was ordered to track the Italian Fleet and make herself visible to the enemy. Meanwhile, Cunningham’s fleet was actually at sea moving to intercept hours before the Sunderland was even in the air.

Ewen Montagu wrote about the success of attacks on Axis shipping from Malta using Enigma decodes from Room 13 at the Admiralty: “We got a huge series of messages with convoys carrying urgently needed petrol, ammunition, etc., across the Mediterranean to Rommel. These were included in the Orange Summaries because of their background value on whether Rommel could or could not carry out his plans, but they were dealt with operationally simultaneously by the O.I.C. (Operational Intelligence Centre). These enabled us to sink a large proportion of these supplies than we would otherwise have done, and thus cripple Rommel’s Army.

“Incidentally, much praise is due to those who so managed our operations that they drained Rommel of supplies without compromising our sources of information; no naval sweep, no submarine patrol, and no bombing flight was ordered to be right on the spot at the right time to intercept. Either one of several air reconnaissance sent to different areas—including, of course, the right one—sighted the German-Italian convoy first or seaborne sweeps were ordered which would ‘just happen’ to reach the right spot at the right time, on a neat piece of navigational planning.”

(Orange Summaries were the summaries of nonoperational deciphered signals with comments provided to the First Sea Lord and the heads of naval operational staff twice a day by Section 17M (M for Montague). None of the operational ships, submarines, or aircraft on reconnaissance knew they were working with the benefit of Ultra intercepts.)

On one occasion, a convoy of five Italian ships sailed from Naples with vital supplies for the Afrika Korps. In this case there was no time for reconnaissance—the decision to attack solely based on Ultra went directly to Winston Churchill. The ships were all sunk by a precise attack that aroused Axis suspicions. To cover this, a radio message was sent to a fictitious spy in Naples, congratulating him for his success—a message that was known the Germans would be able to decode.

In May, the battle for Crete took place; by June 1 the British had evacuated Crete after a disastrous defense. The Royal Navy had suffered severe damage supporting the Army with virtually no air cover. Three cruisers and six destroyers had been sunk, two battleships and a carrier damaged beyond hope of local repair, and a further three cruisers and six destroyers damaged.

However, the losses suffered by the German airborne forces were enough to convince Hitler that no further such operations would take place—such as the proposed invasion of Malta and/or Cyprus.

Also, Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia, was about to start. Fliegerkorps VIII, which had been involved in the campaign against Greece and Crete, was withdrawn for Russia along with elements of Fliegerkorps X; the remainder now took over cover for the rest of the Central and Eastern Mediterranean.

With a total of 351 aircraft, and with so many commitments, the Germans could barely keep 200 of these aircraft operational. They were based mainly in southern Greece and Crete, giving up their Sicilian airfields—but this was to prove a costly mistake. Air raids on Malta fell by a third and were mostly carried out by Italian aircraft. Malta was bolstered by more Hurricanes arriving from the decks of Ark Royal, Furious, and Victorious.

A trickle of supplies to Malta was maintained by cargo submarines. However, in July, six large, fast merchant ships were assembled at Gibraltar to run through in Operation Substance. It was known that the Italians now had five battleships and 10 cruisers ready for service, so Force H was strengthened by ships from the Home Fleet: the battleship Nelson and three cruisers. Bristol Beaufighters from Malta would come out to cover the convoy once Ark Royal and the heavy ships turned back short of the narrows; eight submarines sailed from Malta to watch for the Italian fleet movements, while Wellington bombers attacked the Sicilian airfields.

The convoy got through with some light losses. However, an Italian MTB (motor torpedo boat) managed to torpedo the merchantman Sydney Star; damaged, she reached Malta down by the bows but still under her own power. The convoy brought in 65,000 tons of stores including torpedoes, Hurricane engines, antiaircraft guns, and a large stock of foodstuffs to feed the population and garrison. It was a major landmark in Malta’s survival.

Just after the convoy arrived on the night of July 26, the Italian 10th Light Flotilla, under Commander Vittorio Moccagatta launched a daring raid on Grand Harbour. The dispatch boat Diana was loaded with nine explosive motor boats and sailed from Augusta, Sicily, on July 25. The objective of the raid was to blow a way into the harbor through the bridge on the St. Elmo arm of the breakwater, attack the recently arrived ships, and plant underwater charges on the submarines.

The operation did not go well. Once again the Italian Navy was let down by the Air Force, which was supposed to raid Valletta at 1:45 am to give the attacking craft direction and launch two later raids to cause a distraction. The first raid did not take place, and the other two were late.

The leading human-piloted torpedoes were to blow a gap in the bridge, but once launched they were never seen again, so two explosive motorboats and their pilots were blown up trying to force a way in. However, all they succeeded in doing was bringing the bridge down. By now the shore guns opened up on the remaining MTBs, and all were sunk; Diana escaped back to Sicily. Fifteen of the raiders including Commander Moccagatta were killed and 18 captured.

Commander Marc Antonio Bragadin wrote of the raid, “So ended the Malta failure, the cruellest and bloodiest of all the operations ever undertaken by the crews of the assault craft, but also the focal point of circumstances so extraordinary as to render it without doubt the most glorious of failures; so glorious that any navy in the world would be proud of it.”

At the end of July, further troop reinforcements arrived on the island. Malta’s striking force of submarines and aircraft continued to take a heavy toll of the Axis convoys. From June-October 1941, these forces sank 38 enemy ships totaling 176,588 tons. Malta had survived its first great crisis and was hitting back.

Oliver Ormond was an RAF Pilot Officer of 19 when he flew his Hurricane off the carrier Argus on November 12, landing at the Hal Far airfield on Malta. “This island is odd. It protrudes abruptly out of the sea, yet no point on the island rises to any great height. It is like a uniformly even piece of rock at a distance from the air.

“Four of us share a large, comfortable ante-room…. This is a building called Hal Far House. Maltese architecture is rather pleasing…. The stone buildings seem to resist air raids well, for it just chips bits off instead of the whole building collapsing.”

Two days later Ormond made his first trip into Valetta in a petrol truck. “The petrol lorry was very antique and the driver persisted in sounding his horn at frequent intervals for little or no apparent reason. The town seemed full of happy little children … while goats amused me by disappearing through the front doors of houses or standing haughtily on the pavements.”

In October Malta’s strike forces ratcheted up the pressure on the Axis convoys, and the submarines patrols were increased. A new Fleet Air Arm Squadron of Albacore aircraft arrived at Hal Far. No enemy sea traffic from Sicily to Tripoli was detected after October 18, and Force K with the cruisers Aurora and Penelope and two big fleet destroyers returned to Malta after a five-month absence. Three large cargo submarines arrived to maintain supplies. On each trip one of these boats could carry enough aviation fuel to keep the aircraft based on the island in the air for three days. Air raids remained at a fairly low level, 56 during the month.

The Axis supply convoys were suspended due to the losses. However, Rommel’s troops were desperate for reinforcements and supplies because only a trickle could be flown in. So a convoy of seven merchant ships sailed from Sicily on November 8 for Tripoli, and strong forces were sent to cover the convoy. Enemy submarines were on patrol around Malta to detect the sailing of Force K, and six destroyers were with the convoy, while a covering force of two cruisers and four destroyers was in support.

The convoy was spotted late in the afternoon, and Force K put to sea promptly at dusk; the Italian submarines missed their sailing. That night, in a brilliant moonlight action, Force K attacked the convoy and sank all the supply ships plus two destroyers, while two other destroyers were damaged.

The British ships used their advantage of radar to the utmost. Force K returned to Grand Harbour having suffered neither damage nor casualties. Near dawn, Lt. Cmdr. Malcolm David Wanklyn’s submarine Upholder sank the Italian destroyer Lebeccio.

In November Axis losses had risen to 63 percent of ships sailing to North Africa. The situation had become intolerable; the Italian Merchant Marine was being wiped out and Rommel was crippled by lack of supplies, which led to his defeat by the British Eighth Army in Operation Crusader, followed by the relief of the Tobruk siege in December.

The year 1941 ended with Axis air raids on the island increasing, in particular daylight attacks on the airfields, which met with some success. It had become clear to Hitler that to win the war in the Mediterranean Malta had to be subdued. On December 2, he ordered Fliegerkorps II transferred from Russia to Sicily. Together with Fliegerkorps X, it would form Luftflotte 2 under the command of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring. Four German U-boats were ordered to join six that had entered the Mediterranean in September.

U-81 sank the carrier Ark Royal within sight of Gibraltar on November 13; at that time the British had no modern carrier available to take her place, thus the ability of Force H to cover convoys and fly fighters into Malta was greatly reduced. Twelve days later the battleship Barham was sunk by U-331. She was hit by three torpedoes, and a cataclysmic explosion tore the ship apart; 868 men went down with her—the loss of life at that time only second to the loss of the battlecruiser Hood. This fact was kept from the British public for some months.

The Germans also resurrected the planned invasion of Malta, codenamed Herkules. The landings would take place in two phases; first paratroops would land in the south of the island away from Grand Harbour and would spread out to capture the three main airfields, thus allowing gliders full of troops to land (the small, stone-walled fields of Malta would not allow gliders to land elsewhere). Then a strong Italian force would land by sea in Marsaxlokk Bay.

The Germans even carried out a beach reconnaissance, but little was learned and one party was captured. However, doubts soon gathered in Hitler’s mind: the heavy losses the paratroops had suffered in Crete, the lack of landing craft, and the strong defences of the island.

Count Ciano spoke with the Italian Chief of Staff Marshal Ugo Cavallero on a trip to Salzburg. “During the trip, Cavallero talks to me about the Malta operation. He realizes that it is a tough nut. The preparations under way are being made with a maximum of attention and care, and with the conviction that the attack must take place.

“This is to give the maximum incentive to those concerned with planning. But whether the operation will take place, and when, is another matter, and in this regard Cavallero makes no commitment. As is his nature, he hides behind a great quantity of ifs and buts.”

Rommel’s successful advance in North Africa was continuing, thus the invasion was postponed. Mussolini proclaimed that the advance on Cairo and Suez was the first priority, although Kesselring and Cavallero continued to see the supply route the main necessity.

Now came the climax of Malta’s epic battle as the air assault intensified. In a period of six weeks the towns in the small area around Grand Harbour received a total of 6,700 tons of bombs (by comparison, the November 14, 1940, blitz on Coventry did not exceed 250 tons). In the same period, 21 Royal Navy ships were sunk in the harbors and approaches, and another 13 were damaged. There were 275 raids in March and 283 in May.

On April 14, 1942, Malta lost probably her most famous submarine, the Upholder, with Wanklyn in command, set out on his 28th patrol. The submarine and crew were not seen again and were believed to have been sunk by Italian warships. During 15 months of operations, Upholder sank 11 Axis merchant ships and damaged four others. Also it sank one destroyer and a minesweeper and damaged a cruiser and, remarkably, two Italian submarines—amounting to 128,353 tons of Axis shipping.

For sinking the heavily defended troop transport Conte Rosso a year earlier on May 24, 1941, without a working ASDIC (the British version of SONAR), Wanklyn was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Pilot Officer Oliver Ormond wrote in his diary on Sunday, April 19, 1942: “Yes! I have been awarded the DFC. Today being Sunday, I must wait until tomorrow to go to Valetta to send my mother a cable and buy the ribbon.” That was the last entry in his war diary. He was 20 years and three days old when shot down over the island. His body was not found for five months, as it had landed on a roof. He is buried on Malta at the Capuccini Naval Cemetery.

King George VI would also award the George Cross to Malta to “bear witness to the heroism and devotion of its people.” The medal was displayed in the villages and towns of the island so that every citizen could see it and be aware of their share in earning it.

The Germans also escalated their efforts, increasing the number and size of their raids and sweeping across the island using the latest Messerschmitt fighters, to which the Hurricanes were inferior. Air Vice Marshal Hugh Lloyd arrived to take command of the air defense; he knew the battle would be lost if he did not obtain more Supermarine Spitfires.

In late February the first Spitfires had been flown in from Eagle and Argus, then came two large batches flown in from the carrier USS Wasp, which brought them directly from the UK. After a direct appeal for help by Winston Churchill to President Franklin Roosevelt, the prime minister congratulated the Wasp after her second trip: “Many thanks to you all for your timely help. Who said a wasp couldn’t sting twice?”

Wasp delivered 47 Spitfires in March and a further 61 with Eagle in April. The arrival of the first group from Wasp was tracked by the German radar on Sicily; they reacted quickly. Ninety minutes after the fighters had landed, bombers raided the airfields. Every serviceable Spitfire was put into the air, but nine were destroyed on the ground and a further 29 damaged by rock splinters. The Stukas were diving on each individual plane on the ground, and only pens built of rocks and sand-filled petrol cans prevented much heavier losses. In that one day the Luftwaffe dropped 1,470 tons of bombs on the two main fighter bases.

Argus and Eagle were to fly in 225 more Spitfires in the next four months, while Furious added another 100.

Meanwhile, the Maltese population, holding on amid the shattered buildings, continued with their fast. As the food situation went from bad to worse, superhuman efforts were required, as Joseph Attard noted: “The guns kept firing and shooting down the enemy with the same precision, the fighters kept flying and fighting against bigger odds. Troops, policemen, and civilians—Maltese and British—worked around the clock on airfields filling craters and clearing debris to keep them serviceable. Farmers toiled in their blackened fields, trying to do the impossible.”

The cities of Senglea, Vittoriosa, Valetta, and Floriana were being systematically destroyed. The people had taken to living underground in the great fortress of the Cottonera Lines behind the cities, and ancient tunnels and galleries were enlarged to house thousands of people; caves were dug into rocks, while the disused railway tunnel under the ancient bastions became home for more.

The food situation was rapidly becoming precarious, along with oil and antiaircraft ammunition. The governor estimated that Malta could only hold out until the end of June.

In May the 10th Submarine Flotilla was forced to withdraw to Alexandria as its boats were now being attacked and sunk in harbor. Malta was losing its sting; Italian convoys were passing to North Africa in relative safety with light escorts.

By June it was decided two convoys would be passed through to Malta to ease the situation. Escorting one was the submarine HMS Vigorous from Alexandria with 11 merchant ships, and Harpoon from Gibraltar with six escorted the other. Vigorous, faced with Italian surface forces, including battleships, and heavy air attacks, was forced to turn back. Harpoon, with the benefit of carrier air cover, managed to get two ships through to the beleaguered island and unloaded 43,000 tons of stores, easing the pressure on Malta.

However, much of the supplies were war materials; fuel and food remained strictly rationed. Malta’s weekly ration in mid-1942 consisted of 73 ounces of bread, 3 ounces of fats, 1.75 ounces of cheese, 1.25 ounces of coffee, 3 pints goats milk, 3 pounds of tomatoes, 1.5 pounds of potatoes, plus 8 gallons of water per day. There was no sugar, tea, oil, butter, soap, or meat, and, when the coal ran out, no electricity; the staple diet for months was soup and bread. The only other supplies arriving after Harpoon came from the fast minelayer Welshman and from two cargo submarines, which could get in and out during hours of darkness.

In July there were 188 air raids. However, with 100 operational Spitfires, it was becoming increasingly costly for the Axis air forces (153 of their aircraft were shot down that same month). With better air defenses, the 10th Submarine Flotilla returned early in July. Beaufort torpedo bombers also made successful sorties, sinking 48 ships that month totaling 100,000 tons.

Yet Malta still desperately needed another convoy. Food was becoming critical; if supplies in bulk did not reach the island soon the residents would be starved into surrender. Thus a large convoy was planned; clearly such a big undertaking came to the attention of the enemy. Extra bomber squadrons, E-boats, and submarines were deployed to meet it.

The convoy escort for Operation Pedestal was large: two battleships (Nelson and Rodney), three aircraft carriers (Indomitable, Victorious, and Eagle), three cruisers, and 14 destroyers. The convoy’s close escort, which would sail right through to Malta, consisted of four cruisers and 11 destroyers. The carrier Furious with destroyer escort would deliver another 38 Spitfires to Malta. The 14 merchant ships were all fast, modern vessels.

The Pedestal convoy sailed from the Clyde and Scapa Flow on August 2/3, passing through the Straits of Gibraltar during the night of August 9/10. Early the next day they were spotted by an Italian submarine and the battle was on. The first loss was the carrier Eagle to U-73. The ship had played a large role in the defense of Malta and was a sad loss. By August 15, after an epic struggle, five merchant ships reached the island.

When the American tanker Ohio came slowly into Grand Harbour with a destroyer lashed on each side to keep her afloat after being hit by a torpedo and bombs, she was met by a large crowd, bands were playing and flags waving everywhere along the ancient ramparts and the Barracca Gardens.

The stores (12,000 tons of fuel oil, 3,600 tons of diesel fuel, and 32,000 tons of general cargo) were rapidly unloaded and the tanker pumped out as she settled on the harbor bed. The cost had been high: nine merchant ships, one aircraft carrier, two cruisers, and one destroyer were sunk. Badly damaged were one aircraft carrier, two cruisers and a destroyer—500 men lost.

The supplies brought in with Pedestal at such a heavy cost did not raise the siege, but they did increase the people’s rations and brought fresh hope. Pedestal was the beginning of the end.

The Italian and German Air Forces were now diverted away from Malta to combat the increasing Allied attacks on the convoys from Italy and Sicily to Libya, and several German squadrons were diverted to the Russian Front. The number of raids rapidly dropped in September; there were 20 raid-free nights.

In October there was a brief return to the intensity of air raids suffered in the worse periods, with 1,400 sorties flown against Malta in the first week; 114 Axis aircraft were shot down for the loss of 27 Spitfires. This was during the great battle of El Alamein when the Axis tried to neutralize Malta’s strike forces. Yet, in this month 40 percent of the supplies sent to the Afrika Korps were lost.

In the autmun of the epic year 1942, in which the Axis forces had tried to subdue Malta, knowing that if they failed they would lose North Africa, the Times of Malta clearly identified the island’s role shortly after the victory of El Alamein on October 26: “El Alamein delivered Malta, but Malta delivered Egypt.”

Then in November came Operation Stoneage; four merchant ships, covered by cruisers and destroyers from Alexandria, got through intact, and this convoy did raise the siege. The next convoy, Portcullis, arrived the following month—again with no trouble.

Commander Bragadin, in his History of the Italian Navy in World War II, wrote, “Malta proved to be without doubt the principal factor in the Allied victory in the Mediterranean––on land, at sea, and in the air.”

On June 20, 1943, after the defeat of the Axis forces in North Africa and before the invasion of Sicily the following month, King George VI visited Malta. It was only a year since the island had been on the point of surrender. Admiral Cunningham accompanied the king on his visit. They sailed on the battle-scarred Aurora that had been involved in so many of the Malta convoys and actions in the Mediterranean.

Cunningham wrote, “For obvious reasons the visit had been kept a dead secret, but at 5 am the Maltese were informed of His Majesty’s impending arrival. It was time enough. The Baraccas and all other vantage points were thick with cheering people as the Aurora, flying the Royal Standard, passed through the breakwater at 8 am and moved to her buoys. The king stood on a special platform built in front of the bridge so that all could see him.

“I have witnessed many memorable spectacles; but this was the most impressive of them all. The dense throngs of loyal Maltese men, women and children were wild with enthusiasm. I have never heard such cheering, and all the bells in the many churches started ringing when he landed….

“The King made an extensive tour of the island and we all lunched with the Governor, Field Marshal Viscount Gort, at Verdala Palace. It was the first time a Sovereign had landed on Malta since 1911, and the effect on the inhabitants was tremendous.”

The siege of Malta had cost the Maltese population dearly—1,300 of their number had been killed and 30,000 buildings destroyed or damaged, and it had lasted almost 21/2years—from June 1940-November 1942. But the steadfastness of the people, along with the courage and determination of those who came to save the island, was one of the great British achievements of World War II.