By Duane Schultz

On July 28, 2018, at the Doubletree Hilton Hotel near Dulles Airport, outside Washington, D.C., Mariusz Winiecki, a 42-year-old Polish professor, told an audience of Americans about his experiences growing up in the small town of Szubin, 150 miles southeast of Warsaw. Everyone in the audience knew where Szubin was and what it had been during World War II – a Nazi POW camp.

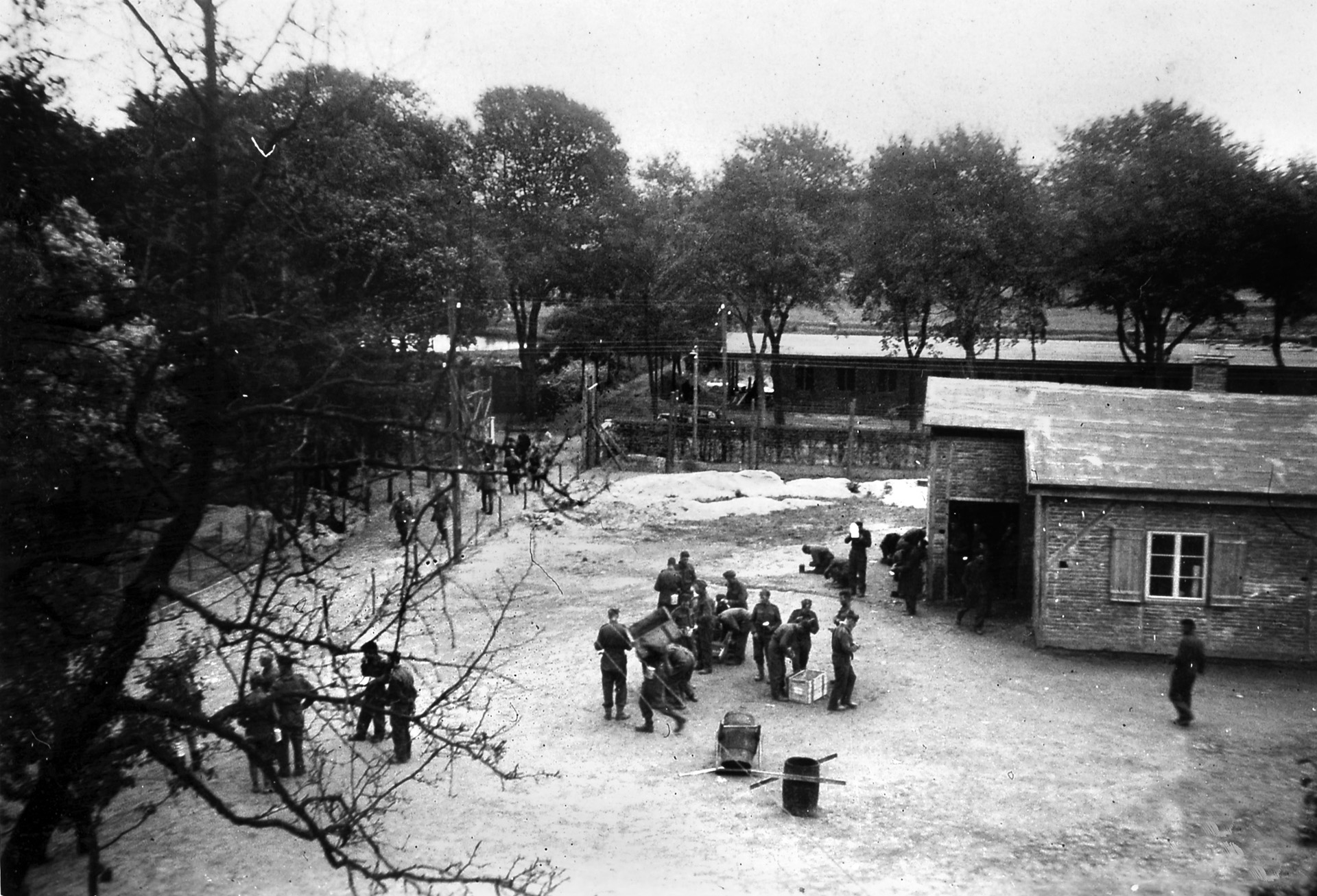

Szubin had been the site of Oflag 64 (an abbreviation of the German term Offizierslager, meaning “Officers’ Camp”). Formerly a boys’ school, it consisted of a large, white, three-story stucco house surrounded by newly-built wooden, brick, and stucco barracks to house the American POWs. The quarters for the Kriegies, as they called themselves (short for Kriegesgefanganen or “war prisoner”), were among the best to be found in any German POW camp.

High-ranking American officers lived four to a room in the main building; each room had its own toilet and sink, rare items in any prisoner-of-war camp. The rest of the officers lived in the barracks. Lieutenant Brooks Kleber, captured at Normandy, recalled, “We lived in dormitories. We were not overcrowded. We had cubicles made out of beds and lockers. Our mattresses were stuffed with straw, which was tolerable.”

Lieutenant Sidney Thal spoke about the camp at age 95 in 2008. He remembered, “We were never abused. We were never mistreated. We operated, acted and reacted solely by the Geneva Convention as much as we could, and so did the Germans.”

The Americans ran the camp inside the barbed wire, while the Germans controlled the outside, and Szubin developed the reputation of being among the best of all the German POW camps. Still, no American ever forgot that it was a prison, and none of them knew how long a sentence they would have to serve. Or if the Germans might decide to kill them all when they started losing the war.

The American commander was Colonel Charles “Pop” Goode, who administered the camp of some 1,400 men with strict discipline, just as if it were an army base back home. The men shaved and exercised every day and kept their uniforms as neat as they could. At a reunion in 2011, Annette Nelson, the widow of Lieutenant Richard Secor, one of the POWs, said that her former husband had told her that the men “wanted to maintain military discipline and create some order to their lives.”

Pop Goode’s executive officer, Lt. Col. John Waters, had been captured in North Africa in 1943. Waters was the son-in-law of General George S. Patton. Both Goode and Waters worked hard to keep up the soldiers’ morale. To this end, Goode acquired a set of bagpipes. Not everyone liked the sounds it made, but each appreciated why he kept playing them—to boost their spirits. In addition, the men acquired a shortwave radio, which was kept hidden and on which they could listen to the BBC news.

The daily lives of the Kriegies were also made more pleasant by a Swedish attorney, Henry Soderberg, known to the Kriegies as “The Welcome Swede,” who visited the camp every two to three months as a representative of the YMCA. He brought books, supplies, and equipment to enable the men to have a variety of recreational programs to help pass their time in confinement.

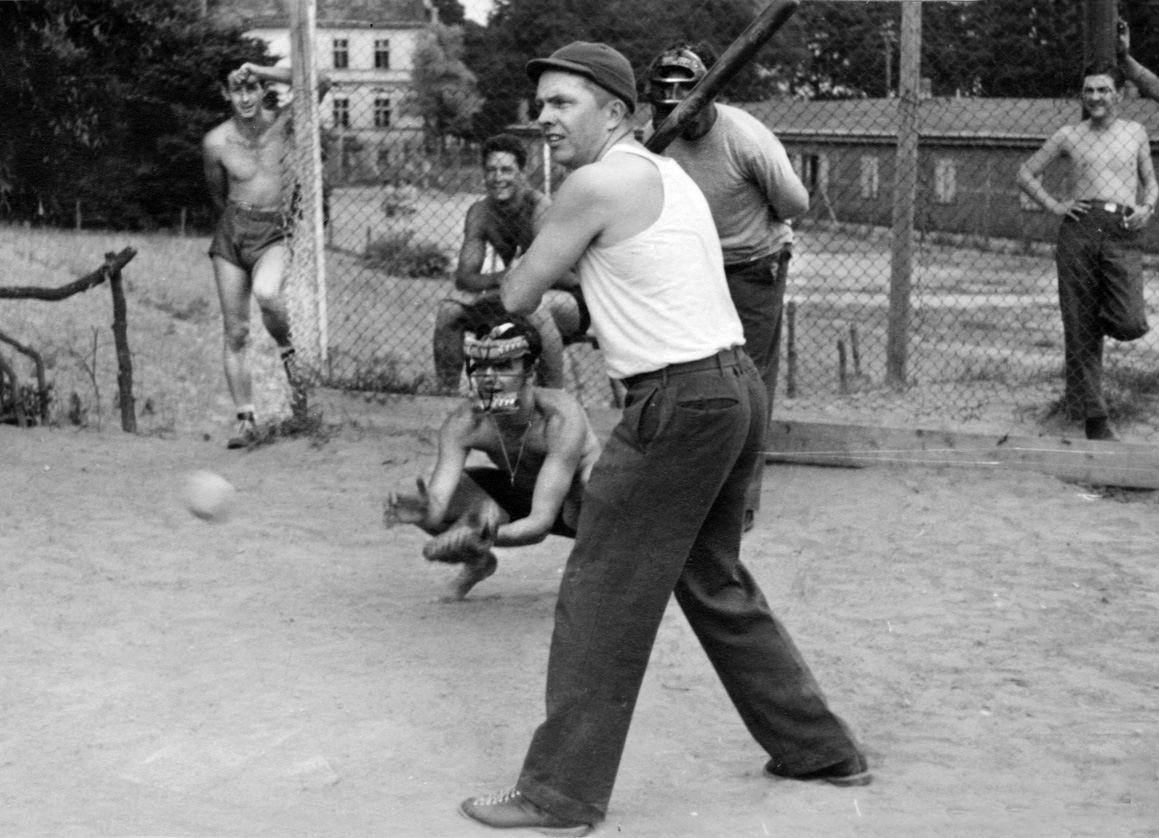

“We had an incredible amount of activities,” Lieutenant Kleber said. “We had a 3,000-book library. We had ‘Szubin Prep,’ in which high-school and college-level courses were taught by the prisoners. We had a jazz band, a classical orchestra. There was a baseball league and a touch-football league.” And, of course, there were the never-ending bridge tournaments.

Polish residents from Szubin would hide in the bushes outside the barbed wire to listen to the musical performances. Wilbur Blaine “Bill” Sharpe recalled that the shows the Kriegies put on and the camaraderie they fostered “kept us alive frankly. That’s what kept us going.”

The Kriegies published a monthly, single-page newspaper, The Oflag 64 Item, which was printed by Anna Kricks, the wife of Willi Kricks, who had owned a printing plant before being conscripted into the German Army. The German-camp administration approved of the project and never interfered with its publication. The Oflag 64 Item continues as a quarterly publication by the active survivors.

The Red Cross brought a food parcel for each man once a week to supplement the meager rations supplied by the Germans. The packages included meat (shared equally by all in the dining hall), as well as milk, chocolate, cheese, and raisins. Nevertheless, the men were almost always hungry. The Germans provided only a near-starvation diet of thin, watery soups, ersatz coffee that tasted so bad many men used it for shaving, and one-sixteenth of a loaf of bread per person per day.

Lieutenant Jay Drake remembered, “Barley was added to many of our soups. Along with the barley you also got meal worms, which, when soaked, sank to the bottom of your bowl. Since you could not afford to discard any food, you never looked into your bowl as you spooned out the last of your soup.”

The lack of food was not the only problem facing the Kriegies in Oflag 64. Despite the programs and activities they set for themselves, their greatest enemies were boredom and apathy, particularly when winter set in. Some succumbed to a type of stupor and lay in bed much of the day throughout the long, cold season, too dispirited to continue trying to be active. Morale plunged with the falling temperatures.

One hardship the Oflag 64 inmates did not have to deal with in Szubin, in contrast to those in other German camps, was brutality on the part of the guards. The Oflag 64 guards left the Americans alone to run the camp, for the most part; some even became friendly.

Lieutenant Colonel Waters said in a 2012 interview that the Americans “could ‘tame’ almost any German soldier if we gave him a D-Bar (the four-ounce Hershey ration chocolate bar that came in Red Cross parcels) and cigarettes. Those poor bastards were hungry. They were smoking dried blossoms from the basswood trees with a little bit of tobacco mixed in with it. They had no decent soap; they had no chocolate bars and with the D-Bar and cigarettes, we could get just about what we wanted from the German enlisted men.”

On a day in early June 1944, three German guards burst into the camp to tell the Americans about the Normandy landings. These guards had previously served on the Russian front. Waters described them as “…those poor damn cripples who were guarding us. Frozen feet, frozen fingers. Broken arms and legs, but [they] couldn’t get in there fast enough to tell us that the U.S. had invaded. They were so pleased about that; they were fed up with the war.”

The Kriegies went wild with excitement when they heard the news, certain that the war would soon end and they would be going home, maybe in only a few weeks. But the fighting dragged on through the summer and into the beginning of winter again. On October 1, 1944, Lt. Col. Waters wrote a cryptic line in his notebook (he called it Remembrances) which echoed the thoughts of most of the men. “And so another month begins. When will this end?” In 2017, Waters’ son, George, visited Szubin, carrying his late father’s faded notebook.

Soon it was time for another melancholy Christmas. “Morale got lower and lower,” Lieutenant Brooks Kleber wrote. “The Red Cross parcels stopped. Weather got colder. The guards told us the Russians were getting closer. Sometimes we thought we heard fighting.”

By mid-January 1945, the Americans noticed daily streams of refugees filing past the camp, trudging west through the snow and bitter cold. The Kriegies watched the endless columns with mounting excitement. Then, on January 20, the German authority told them to prepare to move out in the morning; they were going to a new camp. The German guards, too, aimed to get out of Poland before the Russians came.

The next morning, 1,350 Kriegies started their march to the west; only 490 would reach their destination. Some escaped, others made their way back to Szubin, and some died along the way. It took five weeks to travel 362 miles. “We had blizzards,” Waters wrote. “We had snow; we had sub-zero weather; we had rain; you name it and we had it. It was bitter.”

When they finally reached the new location, Oflag 13-B, near the town of Hammelburg, Germany, the American POWs thought their worst nightmares had come true. Their first sight of the place brought a feeling of oppression; they were about to be locked in like animals. They never imagined they would feel homesick for Oflag 64, but the conditions of the camp at Hammelburg, and of the POWs already confined there, were deplorable, the worst any of the Szubin men had ever seen.

A month after their arrival, on March 27, 1945, an underequipped and undermanned U.S. Army task force of 300 men was sent 60 miles behind German lines. The operation was ordered by General Patton, ostensibly to rescue the POWs at Hammelburg. Patton’s real aim, however, was to save his son-in-law, John Waters. General Omar Bradley later wrote that the mission “began as a wild goose chase and ended as a tragedy.” The noted British historian Alex Kershaw called it “a tragic fiasco.”

Almost all of the men in the task force were killed, wounded, or captured, along with a number of the Kriegies. Colonel Waters was so seriously wounded that it took multiple surgeries over the course of a year before he could return to active duty. The remaining prisoners at Hammelburg, including those who had come from Szubin, were marched to the east in the following days. They suffered from hunger and cold and from the Allies’ bombing and strafing raids. The number killed during this agonizing trek remains unknown.

Considering the misfortunes at Hammelburg and its aftermath, it is hardly a surprise that so many of the Kriegies looked back on the Oflag 64 camp as almost more a haven than a prison. They formed an active survivors’ association that held reunions beginning in 1947, and many of the men and their families traveled to Szubin in later years to relive their memories.

And that explains why a Polish professor so captivated the audience in the hotel outside Washington, D.C., more than 70 years after the end of the war. The Americans listening to him were the children and grandchildren of former POWs, along with one camp survivor, Bill Sharpe, then 96 years old.

Professor Mariusz Winiecki told them how, as a boy, he had walked through a cluster of rundown buildings partially enclosed by a barbed wire fence on his way to school every day. As he got older, he became more curious about what the place had been. When he found out it had been a German POW camp for Americans, he was eager to learn more.

“My generation does not know what happened in the camp,” Winiecki said, “because during the long Russian occupation, the Polish people were not allowed to celebrate, or even recognize, anything to do with the role of American soldiers in World War II.” The more he learned about the camp, the more determined Winiecki became to make the residents of Szubin “aware of World War II and the atrocity that war can cause.”

Winiecki told his audience in 2018: “I want to tell your stories, your fathers’ stories.” And how better to do that than by establishing a museum at the site of the camp, to recreate the life of the American POWs who lived there?

The children and grandchildren of the POWs agreed, as did the lone survivor. “I just figured it would be nice to preserve it even though it was a place of adversity,” Bill Sharpe said. He recalled that his weight dropped from 150 to 96 pounds during his 19 months in captivity. But he also noted that he had “a lot of pleasant experiences there,” such as the theater and the music, and how the prisoners all tried to take care of each other.

And so, as one of the last survivors of Oflag 64, Sharpe volunteered to take the lead role in raising funds for the commemorative museum.

Once he returned to Poland, Winiecki worked with Szubin’s mayor and the head of the reform school that now occupies the prison compound, and he persuaded the national government to turn over ownership of one of the remaining prison buildings to serve as the site of the museum. He also started a blog, OFLAG 64 RECORD, on which he regularly posts reports of his progress.

His hope is that sometime this year, the 75th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe, the memorial to the Kriegies of Oflag 64 will be open as a tribute and a testimony to those who were there.

Duane Schultz has written numerous articles and books on military history, including Crossing the Rapido, Into the Fire: Ploesti, and Patton’s Last Gamble. See www.duaneschultz.com.