By Matthew Peszek

The Eighty Years’ War between Spain and the Netherlands, which lasted from 1568 to 1648, developed not only from economic difficulties but also from religious tensions that eventually resulted in several Dutch riots in 1566. The riots caused the Spanish monarch to send Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, the Duke of Alva, to regain control of the situation, but his harsh tactics and personal cruelty caused many Dutch to see him as an oppressive tyrant. As a result, people who considered themselves loyal subjects of the Spanish Empire revolted. The revolt would turn quickly into a full-fledged rebellion.

After the duke’s arrival and his subsequent cruelty to the populace, the Dutch instigated a low-level guerrilla war against the symbols of a hated government, as personified by Alva. Through the use of inflammatory prints and engravings, Dutch opponents transformed the duke into an icon of all-encompassing evil. These prints continued to be published into the early 17th century, well after the duke’s death in 1588. Memories of his reign were conjured in prowar prints and pamphlets in order to create anti-Spanish sentiment and perpetuate the war.

Violence against the Catholic Church began in the southern Netherlands town of Steenvorde on August 10, 1566, when a mob stormed the church, broke stained-glass windows, and smashed religious statuary and altar pieces. From Steenvorde, the rioting spread quickly to the surrounding towns of Belle, Ieper, Poperinge, Dirksmuide, and South Winoksbergen. The outbreak then moved east to Oudenaarde on August 18 and Antwerp on August 20. From Antwerp, the riots spread throughout the towns in the province of Brabant, and within a few days the fervor had made its way into the northern Netherlands as well, where it spread throughout the province of Holland and into the neighboring provinces of Friesland and Groningen.

The ongoing violence against the Catholic Church forced King Philip II of Spain to act. Accordingly, he dispatched the Duke of Alva to the Netherlands to provide a Spanish military presence, punish those responsible for the riots, and restore religious unity among the population by wiping out heretical sects. The regent of the Low Countries, Margaret of Parma, wrote to Philip II begging him to reconsider. Margaret argued that Alva’s presence in the Netherlands would create an even more volatile situation between Spain and the general populace, since the duke was known for his heavy-handed measures. Philip rejected her petition, and the Duke of Alva and his army arrived in the Low Countries, establishing themselves in Brussels and building a citadel in Antwerp, where anti-Spanish sentiment remained strong.

The duke was not long in providing ammunition for his critics. The arrest and execution of Lamoral, Count of Egmond, and Philippe de Montmercy, Count of Hoorn, occurred almost immediately after the duke’s arrival in Brussels. Convicted of treason, the counts were condemned to death on June 4, 1568, and beheaded the next day in Brussels. The creation of a so-called Council of Blood also emphasized Alva’s tyranny of the populace. While the council was originally meant to find and punish only those directly responsible for the 1566 riots, over time it evolved into the indiscriminate persecution of Calvinist preachers, their congregations, and anyone suspected of supporting rebellion against Spain. Alva’s imposition of various tax systems, most notably the “tenth penny,” a 10 percent tax on all transactions, was also highly unpopular. While the tenth penny was never collected, the mere idea of such a cumbersome tax created the perception of Alva as a greedy Spaniard.

Such moves ultimately helped to create a “black legend” of Alva and the Spanish reign in the Netherlands. When Philip II gave him the mission of regaining control of the seemingly uncontrollable Low Countries, Alva made it clear that he intended to act ruthlessly since he believed that it was “better that a kingdom be laid waste and ruined through war for God and for the king, than maintained intact for the devil.” As far as Alva was concerned, he would rather see the nation totally destroyed than fail in his mission. His disdain for the Low Countries and its inhabitants helped solidify his image as a heartless tyrant and would ultimately lead people to throw their support behind the exiled Dutch champion, William of Orange.

Thanks to Alva’s draconian actions, opposition printers and engravers had much at their disposal to create a negative image of the duke. Not only did his harsh actions negatively impact his perception in the public mind, but his personal appearance also played into the image of cruelty. Contemporary sources described the duke as “tall, thin, erect, with a small head, a long visage, lean yellow cheek, dark twinkling eyes, a dust complexion, black bristling hair, and a long sable-silvered beard, descending in two waving streams upon his breast.” His gaunt and devilish appearance provided additional fodder for propagandistic prints depicting the duke as the devil incarnate and perpetuating the idea of an oppressed Dutch people living under a “reign of Satan.”

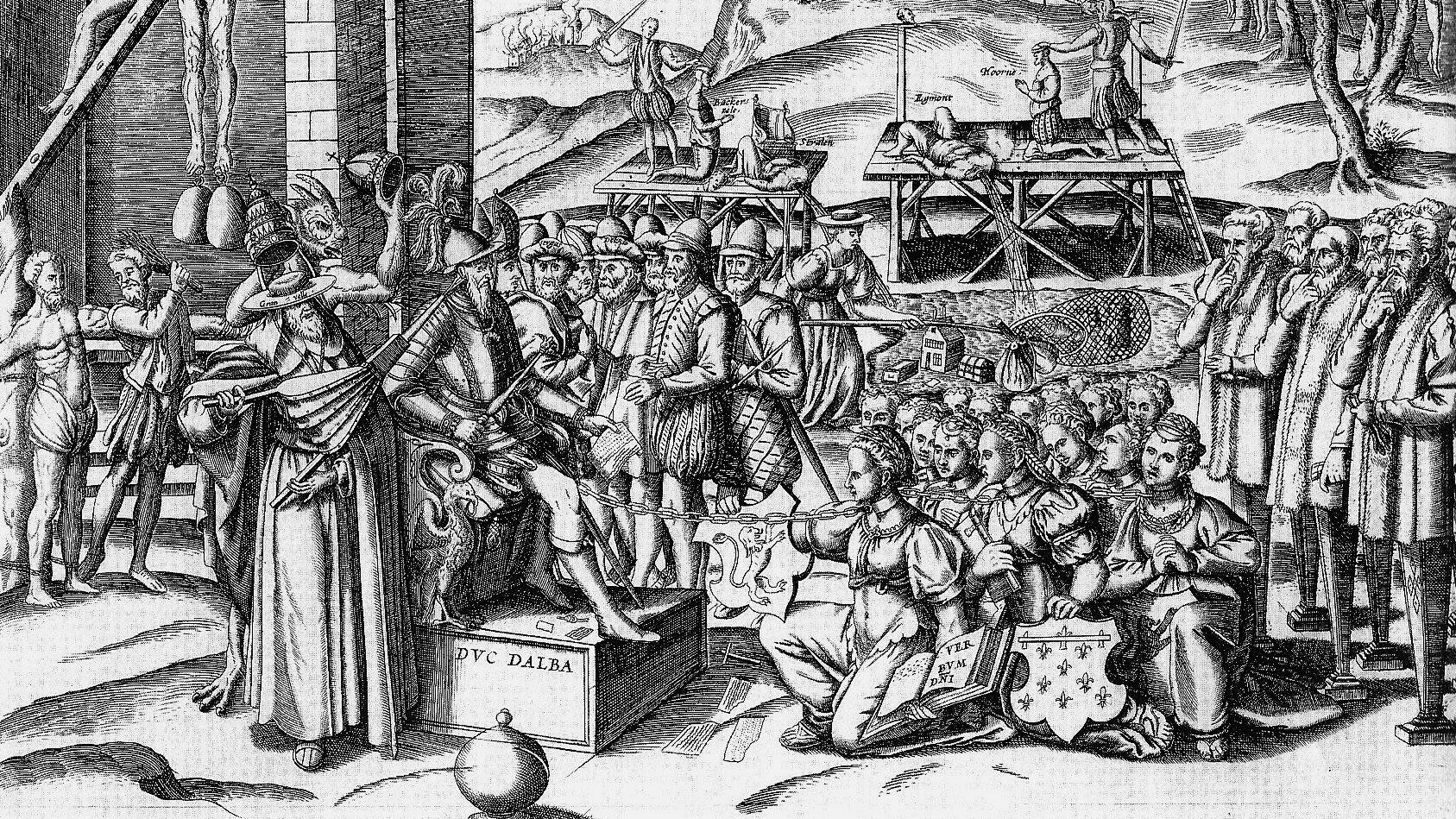

The print Throne of the Duke of Alva (Figure 1) from 1569 shows the duke sitting on a throne while Cardinal Granvelle blows a bellows in his ear symbolizing the bellows of hell. Above the two men is a winged demon placing the papal tiara on the cardinal’s head. The act of being crowned by a demon is a direct attack on the idea of a monarch’s divine right to rule and emphasizes that the duke’s rule was not ordained by God but by Satan. To the side are various members of the Council of Blood, including two labeled “Vargas,” and “Del Rio.” They represent Juan de Vargas and Lodewijk del Rio, who were members of the council and well known Alva yes-men. Kneeling in front of the duke are personifications of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands, bound together in chains, symbolizing their enslavement to the Spanish Empire. Standing behind the provinces are members of the States General, who have pedestals instead of legs, connoting their ineffectiveness during Alva’s reign. Behind the duke’s throne are two scenes of torture. In one, a man is getting scourged at a pillar, while the other depicts a victim being strung up with weights on his feet.

The background shows various execution methods such as burning at the stake, impalement, hanging, and beheading. The figure about to be executed is identified as Jehan de Casembroot, a writer, secretary, and counselor to Count Egmond. The figure already beheaded is identified as Antoon van Straelen, a friend of William of Orange and the mayor of Antwerp. Both Casembroot and van Straelen were Catholics who had sworn loyalty to Philip II but were executed by Alva nevertheless. This indicates Alva’s irrationality, cruelty, and heavy-handed methods, even to those who considered themselves loyal subjects of the Spanish king.

A second print casts Alva as an image of tyranny and contrasts him with his Dutch rival, William of Orange. The engraving, possibly by Theodoor de Bry, William of Orange and the Duke of Alva (Figure 2) shows the two opponents facing each other with allegorical personifications representing the character of each leader. William is holding a morning star, which can also be seen as a commander’s baton. He is about to be crowned with a laurel wreath, a symbol of victory, by the personification of Honor, while Wealth lies at his feet and offers bags of money from her pot of gold. Meanwhile, the elderly figure of Wise Counsel reclines slightly behind William. On the right, Alva holds shears and a commander’s baton as well. He is about to be given the Spanish crown by personifications of Falsehood and Envy. At the Duke’s feet lies Poverty, which symbolizes the Dutch people, and standing behind Poverty is a nude representation of Belgica, symbolizing the Netherlands. Belgica is nude, while Alva holds shears to strip away her wealth.

This form of propaganda follows a common motif in which one side is associated with a list of virtues and the other is associated with vices that are opposite of the virtues. William of Orange is associated with Wealth, while Alva is associated with Poverty. William is shown in other prints with personifications of Humility, Justice, Truth, Love, and Generosity, while the Duke of Alva is given the opposite vices of Pride, Injustice, Falsehood, Hatred, and Greed. This idea also applies to historical and biblical figures as well, with William portrayed as a leader of oppressed people such as Moses and King David, while Alva is shown as Pharaoh, Herod, Nero, and Attila the Hun.

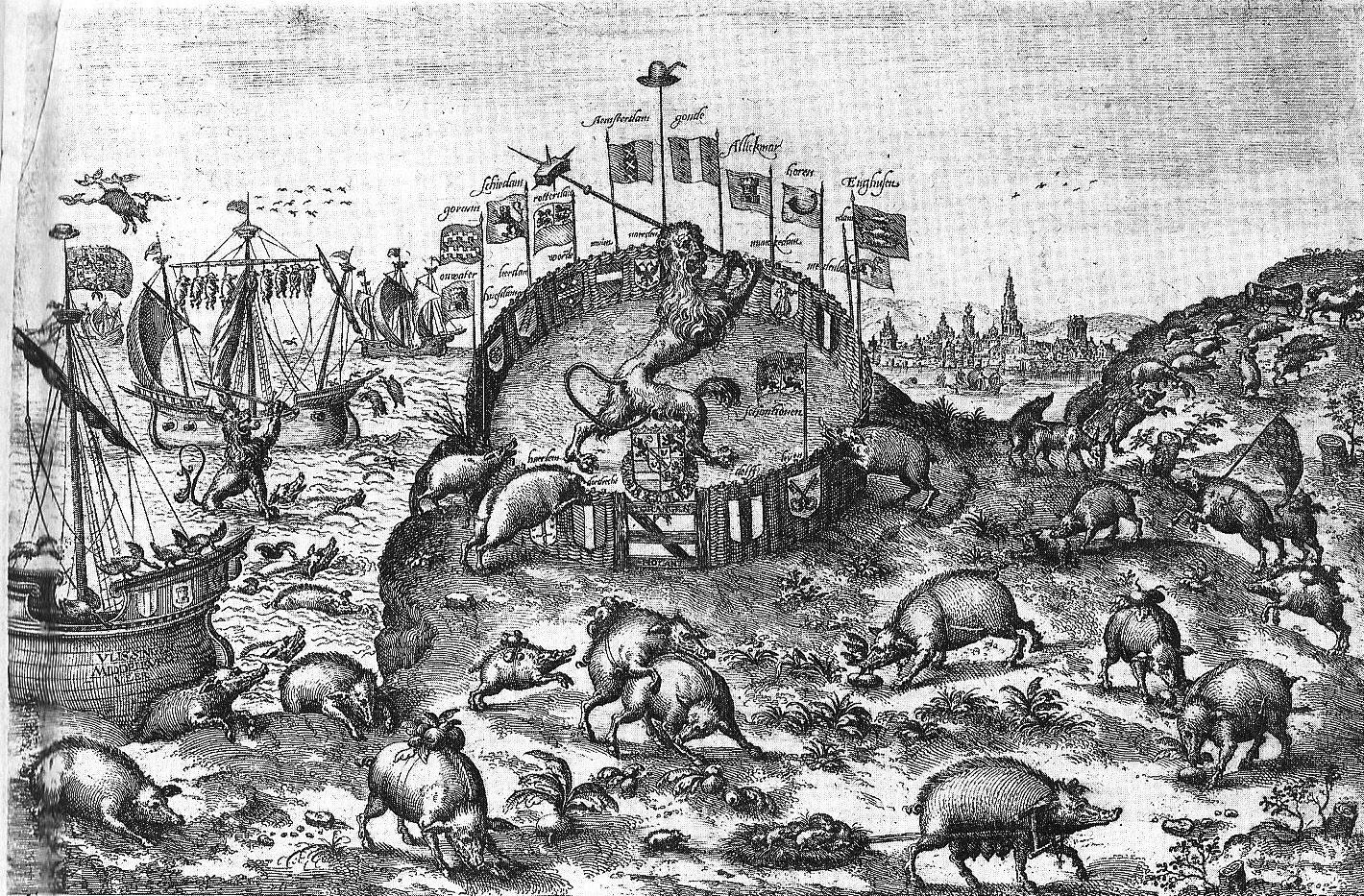

The next type of print is more humorous in nature, yet still biting. It features personifications of animals representing the opposing nations. Stop Rooting in My Garden, Spanish Pigs (Figure 3) shows a large number of pigs roaming about eating the food of the land. While some pigs scour the land, others assault an enclosure bearing the coat of arms of various cities in the northern Netherlands, including Amsterdam, Gouda, Haarlem, and Dordrecht. In the center of the enclosure is the Netherlands lion, fighting off the approaching pigs with a two-handed mace. On the left of the print is a battle between geese and pigs. The geese refer to the Dutch and allude to the “Sea Beggars,” who conducted hit-and-run guerrilla attacks against Spanish galleons and treasure ships. In the battle, flocks of geese chase the pigs off the boats and attack them in the water. One pig is carried off by a flock of geese, while a ship’s rigging is strung with a row of hanged pigs.

After the Duke of Alva’s death in 1588, his image was still being used in prints and books as a catchall symbol for Spanish tyranny. After Philip II’s death in 1598, the Netherlands passed into the hands of his daughter, Isabella, and her husband, Archduke Albert of Austria, who became the new governor-general of the southern Netherlands. This created a split between the Seventeen Provinces. While some of the provinces wanted to make peace with Spain, others wanted to continue the revolt started by William of Orange.

The Slaughter of Zutphen (Figure 4) was created after the death of Alva in 1588. The print appeared in 1620, almost 50 years after the actual event. Historically, the slaughter of Zutphen was carried out in November 1572, when townspeople were thrown into the icy river to freeze or drown. Zutphen was one of the cities in the province of Gelderland that had thrown support behind William of Orange. After Spanish forces managed to recapture Gelderland, the Duke of Alva’s son, Don Fadrique, ordered the execution of the townspeople to send a message to other provincial cities to capitulate. After the massacre at Zutphen, the cities of Bolsward, Sneek, and Franeker hastily surrendered to Spanish forces.

The print shows soldiers in Spanish clothing and armor attacking a group of naked victims whose hands are bound and clasped in prayer. Several of the dead have been dumped into the icy waters, while others are about to be. In the background, six men hang from a tree while another man hangs upside down with his hands also clasped in prayer. This print was one of a series of 16 created in the Spiegel de Spaansche Tiranny in Nederland [A Mirror of the Spanish Tyranny in the Netherlands], which was meant to whip up anti-Spanish sentiment to continue the war against Spain by reminding people of the pain and suffering they had endured under the reign of Alva.

Despite the fact that the latter work was printed in the early 17th century, almost half a century after the actual event, it was meant to keep alive the memory of Alva for political purposes. Such efforts worked. The devilish duke is still remembered today for creating a system of terror under which all Netherlanders lived “in the shadow of the gallows and the stake.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments