By Michael D. Hull

Near the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and beside the grave of world heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis in Arlington National Cemetery is the resting place of a film star who chose to be remembered first and foremost as a U.S. Marine.

Lee Marvin achieved acclaim with many film and television portrayals, but he never forgot that he had found a home in the Marine Corps and was proud to be a wounded veteran of the Pacific theater in World War II. His life echoed the familiar refrain, “Once a Marine, always a Marine.”

As a leatherneck and as an actor, on the screen and in real life, he worked and played hard —a rough-hewn maverick who brawled frequently, drank too much, and never hesitated to defy authority. He said that he learned an important lesson in the corps: “Life is every man for himself. You can’t ever let your guard down, and the most useless word in the world is ‘help.’” But the oft unruly free spirit could be kind, understanding, and steadfast.

Marvin was born in New York City on February 19, 1924. He and his brother, Robert, who became an artist and teacher, were the sons of Lamont Marvin, a decorated World War I Army captain and advertising executive, and Courtenay D. Marvin, a fashion writer and beauty consultant. Lamont collected guns and instructed his sons in handling firearms.

When Lamont became advertising manager for the Florida Citrus Commission in 1940, it was decided that Lee should attend St. Leo’s Preparatory School, near Dade City, Florida. The lean, muscular youth hated it as he had previous schools, but he shone in track and field. In his free hours, he hunted feral pigs with a bamboo spear in the woods near the campus. He was expelled just shy of graduation for his habitual flouting of regulations. He then attended a high school for three years before dropping out.

By this time, America was at war, and the restless rebel knew what he wanted to do— join the Marine Corps. “I knew I was going to be killed,” said the fatalistic Lee. “I just wanted to die in the very best outfit. There are ordinary corpses, and Marine corpses. I figured on the first-class kind and joined up.”

His father was delighted and decided to get into the war himself. At the age of 51, he went back into the army and was shipped to England, where he helped to set up antiaircraft gun emplacements that destroyed a number of German V-2 rockets in 1944-45. Lamont survived the war as a top sergeant with more decorations.

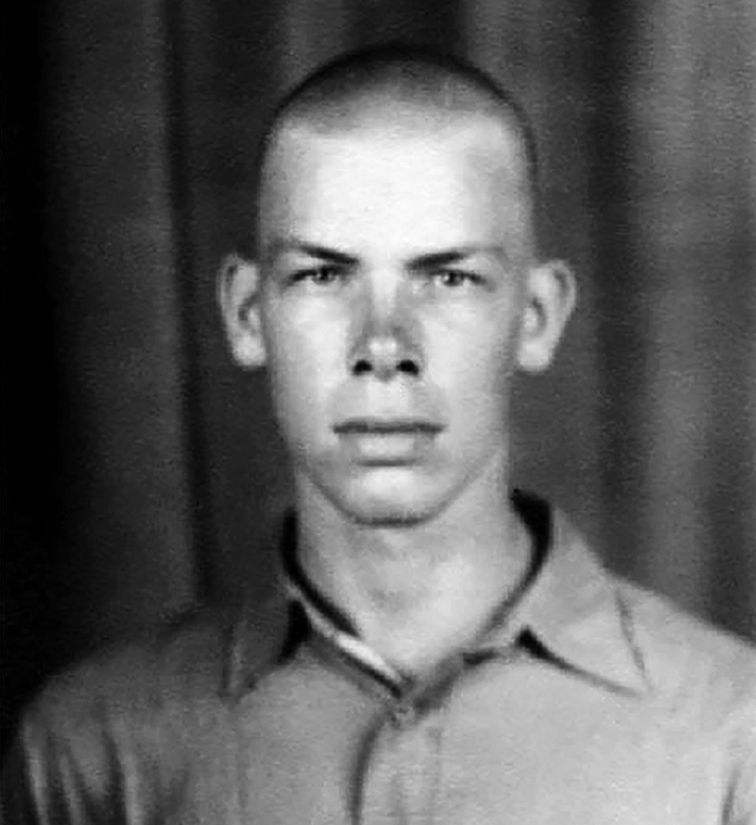

After his brother joined the Army Air Forces, 18-year-old Lee enlisted in the Marine Corps in New York on August 12, 1942. He underwent basic training at the Parris Island, South Carolina, Recruit Depot and the New River, North Carolina, Marine Base. He excelled in boot camp, and, thanks to his father’s influence, made sharpshooter. He missed expert status by one point. He was promoted to corporal at New River, assigned to a service company at Camp Elliott, near San Diego, California, and received instruction in demolitions. He mastered combat training but was still rebellious, and some minor scrapes saw him reduced to private, confined to barracks, and assigned to a month of mess duties.

Disgruntled and eager to see some action, his chance finally came when he was assigned to D Company of the 4th Tank Battalion, 4th Marine Division. The scout-sniper unit, soon to be redesignated as a reconnaissance outfit, shipped out for the Pacific theater in January 1944 to take part in Operation Flintlock, the invasion of the Marshall Islands by leathernecks of Major General Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith’s Fifth Amphibious Corps and Army troops of Major General Charles H. Corlett’s 7th Infantry Division. The Marshalls’ sprawling chain of 32 atolls included two major Japanese bases, Kwajalein and Eniwetok.

Marvin’s role as a scout-sniper with the reconnaissance company of the 24th Marine Regiment was more suited to his personality than the spit and polish of other outfits. Rank and regulations were set aside, and the emphasis was on physical prowess, independence, and camaraderie. Paddling in small rubber boats, Marvin and his comrades were sent in to reconnoiter Kwajalein on the night before the invasion early on Tuesday, February 1, 1944. His introduction to the chaos of combat was a rude awakening.

“If you were fired on, you were supposed to throw a poncho over your head, whip out a blue flashlight, and draw an ‘X’ on the map where the fire was coming from,” he reported. “Well, I don’t think anybody actually threw a poncho over their head, and nobody fired back, either. Because once you fired, you were dead. Of course, we’d all get miserably lost and screwed up.

“The next morning, if you got that far, the sun would come up, and there would be the whole U.S. Navy out there because it’s D-Day. And they would be shelling you because if they saw you they figured you were Japs and nobody told them otherwise. So, God, it was absolute confusion. You’re hit by friend and foe. So you eventually swim out to a reef and pray, and hope, goddam it, that somebody’s listening.”

The Marines captured Kwajalein on February 4, and Marvin saw more action later that month. He and his comrades scouted Eniwetok before landings by Marines and Army troops on the atoll’s Engebi and Parry Islands on February 18-19. Marvin’s luck held through several more missions before he was shipped to Maui, Hawaii, for leave. After receiving some more training, he was then assigned to I Company of the 3rd Battalion, 24th Marine Regiment. His next stop would be Saipan in the Marianas. The 70-square-mile island was needed as a forward base for B-29 heavy bomber raids against Japan.

General Smith’s 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, supported by the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, started landing on the morning of Thursday, June 15, 1944. The leathernecks were reinforced two days later by Major General Ralph C. Smith’s 27th Infantry Division. Saipan was fiercely defended by 32,000 Japanese troops, and the month-long campaign was bitter and costly.

After going ashore on Yellow Beach 2, Marvin and his company crawled forward through brush and into large cane fields, where stood thousands of sticks topped by sake bottles. Marvin assumed that they were being used as insulators for wires which had been knocked down, but he was wrong. They were artillery markers.

“They had us nicely pinpointed on a checkerboard,” he reported. “They didn’t miss. The artillery got very bad, and all the bombing was coming down real heavy.” Casualties began to mount, but Marvin and his surviving comrades pushed forward and took shelter in a long trench. By the end of the day, he estimated, the Marines and the enemy were only 30 yards apart.

After losing more men that first night, I Company pushed toward Aslito Airfield, which was eventually taken by the 165th Infantry Regiment, a New York National Guard outfit, and renamed Isely Field. After getting pinned down and losing more men, Marvin’s company was pulled out.

On Sunday, June 18, the fourth morning of the campaign, I Company headed into “Death Valley.” Its objective was 1,554-foot limestone Mount Tapochau, an extinct volcano. But the company was ambushed before it could start its ascent. Shellfire from 27 Japanese emplacements rained on the leathernecks. In 15 minutes, the company was reduced from 247 men to six. “It was just decimation,” said Marvin, one of the survivors.

Then it was suddenly his turn. His luck ran out and he “got nailed” by an enemy machine-gun round. Ripping through his lower back, narrowly missing the spinal cord, and severing his sciatic nerve, it tore a nine-by-three-inch hole in Marvin’s buttocks. “Jesus Christ!” he yelled. “I’m hit!” Another leatherneck shouted, “Shut up, we’re all hit.” Marvin said later, “There are two prominent parts of your body in view to the enemy when you flatten out—your head and your ass. If you present one, you get killed. If you raise the other, you get shot in the ass. I got shot in the ass…But I was alive and still had my .45 automatic, which gave me some blast if I needed it.”

Marvin was placed on a stretcher, given a shot of morphine, and laid with the other wounded men. A few seconds after he had gulped some water from a plasma bottle, a captured Japanese ammunition dump 150 yards away exploded. The tremendous blast blew Marvin off his stretcher, and he landed squarely on his lacerated behind.

As the wounded were carried back to the beach, Marvin and another man were placed into a jeep. The vehicle started off but headed into enemy-held territory. The driver realized his mistake, however, and swiftly wheeled around and made it to the beach. That night, Marvin was loaded into a passing landing craft and taken out to the hospital ship USS Solace. After six months of combat, during which he assaulted 21 enemy-held beaches from Kwajalein to Saipan, the war was over for him and he was finally safe. But he wept for the men who were not and experienced nightmares for the rest of his life.

Marvin spent the next 13 months in naval hospitals. He was awarded the Purple Heart while in a hospital on Guadalcanal, and later received a Presidential Unit Citation, a letter of commendation with ribbon, and campaign medals. At the Boston Naval Hospital, he learned that he had closely escaped being permanently paralyzed. He was discharged on July 24, 1945, at the Philadelphia Marine Barracks with a modest disability pension.

Marvin was soon reunited with his father and brother when they returned from Europe. Like many returning veterans, the three men were bewildered and depressed. A few months later, Lamont, who had soldiered in both world wars, suffered a total breakdown. Courtenay Marvin, meanwhile, gave up her career and moved the family to a new home in the small Ulster County town of Woodstock, New York.

After trying unsuccessfully to rejoin the Marine Corps, Marvinb worked odd jobs and became a plumber’s assistant. It was a humble existence, but it eventually led him to a new career.

A local doctor befriended the veteran who mowed his lawn, inviting him on fishing trips. On one trip Marvin met the manager of Woodstock’s Maverick Theater. While working on the theater’s backed-up toilet one day, Marvin’s attention was diverted by the bustle of a summer-stock rehearsal.

He was intrigued by the camaraderie and tension, reminiscent of his Marine days. The director had asked the theater manager to find a tall, boisterous man to fill in for a sick actor. Marvin got the bit part.

With the aid of the GI Bill of Rights, he studied at the American Theater Wing in New York, and from 1948 to 1950 played minor roles off-Broadway, on live TV, and in repertory. He was in Herman Melville’s Billy Budd on Broadway in 1951.

That same year, Marvin made his film debut in You’re in the Navy Now, a comedy about a hapless destroyer crew, starring Gary Cooper. Impressed with Marvin, director Henry Hathaway enlarged his role, and introduced him to an agent in Hollywood.

In a series of westerns and melodramas, Marvin was usually a mean gunman, gangster, or social misfit, before landing better roles. He appeared with Tyrone Power and Patricia Neal in Hathaway’s 1952 Cold War thriller, Diplomatic Courier, and the following year in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat, a police drama with Glenn Ford, and The Glory Brigade, with Victor Mature and about Greek infantry in the Korean War.

Marvin had a breakout year in 1954. He played Marlon Brando’s snarling rival, Chino, in The Wild One. He was in The Raid, based on a real-life attack on a Vermont town by escaped Confederate prisoners. In The Caine Mutiny with Humphrey Bogart, Marvin played a slovenly sailor. In 1956, he was in two more landmark war films—as a wounded soldier in The Rack, with Paul Newman, and as a colonel in Robert Aldrich’s Attack!, starring Eddie Albert as an infantry captain in the Battle of the Bulge.

After landing roles with John Wayne in two John Ford films—the acclaimed western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and the comedy, Donovan’s Reef (1963)—Marvin finally established himself as a star in 1965. In the western comedy, Cat Ballou, starring Jane Fonda, he won a best actor Academy Award with his dual role as a drunken gunman and his desperado twin.

In 1967, Marvin gave one of his best leading performances in the box office hit, The Dirty Dozen. Cast with former Marines Robert Ryan and Robert Webber, Navy veteran Ernest Borgnine, and ex-B-29 tail-gunner Charles Bronson, Marvin portrayed hard-bitten Major John Reisman. The film was nominated for four Oscars.

Marvin starred in two low-budget war films released in 1968. In Sergeant Ryker, he was an Army sergeant court-martialed for alleged treason during the Korean War. In Hell in the Pacific, he and Toshiro Mifune were opposing soldiers, one American and one Japanese, stranded on a deserted atoll.

His later films were less than memorable, with the exception of Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One (1980). Marvin was cast as a sergeant and World War I veteran nurse-maiding four young riflemen as the U.S. 1st Infantry Division slogs through North Africa, Sicily, France, Belgium, the Rhineland, Germany, and Czechoslovakia.

The Saipan veteran did more than turn in one of his best roles. Seeing his fellow actors had no idea of how to handle weapons, he acquired M-1 rifles and ammunition and had them fire blanks off the set. He held target practice and taught them how to break down and clean their weapons. He even had them take rifles home at night for cleaning.

Fuller’s masterpiece was seen as one of the most telling films about the European war. A Big Red One veteran and Silver Star winner, Fuller also had directed The Tanks Are Coming, The Steel Helmet, Fixed Bayonets, and Merrill’s Marauders.

Marvin could be unruly and unpredictable, but his loyalty to the Marine Corps was unshakable. He was proud to have served and missed the esprit de corps. He often attended reunions of the 4th Marine Division Association. In 1986, he told a Leatherneck writer, “When I see a young Marine in the airport, I think about how this guy is getting his presence together—that boot camp is doing its job. There’s a mettle to him standing in the airport wearing that uniform with his rifle badge. Yeah, I guess I see myself.”

Marvin, 67, died of a heart attack on August 29, 1987. His Arlington headstone reads, “Lee Marvin, PFC, U.S. Marine Corps, World War II, Feb. 19, 1924-Aug. 29, 1987.”

Lee Marvin stormed 21 beaches in six months??????

Mr. Seeds,

Thank you for subscribing to Warfare History Network and taking time to ask a question. In response, I would offer that a number of tactical and small-scale amphibious operations occurred in the Pacific War during the six months between Kwajalein and Saipan. For example, in the days immediately following Kwajalein the following took place: Ebeye Island on 3–4 February, Engebi Island on 18–19 February, Eniwetok Island on 19–21 February, and Parry Island on 22–23 February. The author was certainly not alluding to major amphibious operations but to those smaller landings that were carried out to eliminate small Japanese garrisons and secure other islands and atolls in the vicinity of US personnel. Author Hull has written for our publication for years, and his research has been proven reliable. Many thanks for your question and for engaging us. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Regards,

Michael E. Haskew

Editor

WWII History

A really interesting article about one of my favorite actors.