By William E. Welsh

In 1194 English King Richard I returned to England from his long absence on the Third Crusade and set about recovering the castles his younger brother John had taken in his absence. Upon learning Richard had returned safely, the garrisons of most of the castles held by John yielded without a fight. But not the stubborn garrison at Nottingham Castle.

On March 25 Richard arrived at Nottingham determined to take the stronghold by force. Richard donned harness and helmet, for he was always in the thick of the fray. As he moved about, several bodyguards carried large shields in front of him. Richard’s knights and men-at-arms fought their way into the barbican and outer bailey on the first day. The next day, Richard deployed catapults against the castle walls.

On the third day of the siege, two defenders were allowed into the king’s presence to confirm that he had indeed returned to England and that there was no hoax being perpetrated against the garrison. “Well, what can you see?” he asked them. “Am I here?” This was enough to convince those who doubted Richard was among the besiegers. The garrison surrendered on the fourth day.

Richard pardoned the garrison troops, but he made each one pay a fine. This move was intended to expand his coffers, for he was gathering funds by every conceivable means to finance a protracted war on the Continent against French King Philip II to regain lands that were his by right of being the Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou.

Richard had perfected his fighting skills on the Third Crusade. Even before he was crowned king of England on September 3, 1189, Richard had begun preparations to participate in the crusade. The young monarch took the cross not only to atone for his sins, but also as a chance to demonstrate his martial skills against the Muslims.

Richard quite literally fought his way to the Outremer. While in Sicily, his troops stormed Messina. Afterward, he conquered Cyprus by defeating its Byzantine despot. He arrived in Acre on June 8, 1191, to find a siege already in progress. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa had died in Anatolia on his way to join the crusade. Richard shared command with Philip, who had reached Acre a short time earlier.

Acre fell to the crusaders in mid-July. Both Philip and Richard had fallen ill with a scurvy-like disease called arnaldia. Philip used his illness as an excuse to depart, but he really left to address pressing political matters back home, one of which was a succession crisis in Flanders.

Although Richard failed to take Jerusalem largely because he believed it too difficult to capture and hold, his army captured a number of Muslim-held ports and towns in Palestine that shored up the Kingdom of Acre and helped it survive for another century. Richard’s victories against An-Nasir Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, better known to the West as Saladin, in pitched battles at Arsuf and Jaffa solidified his reputation as a first-rate commander. The experience enhanced his logistical, administrative, and leadership skills.

Richard was keenly fond of war. He fought alongside his troops not only to inspire them, but because he loved fighting. The upshot was that he exposed himself to great personal danger on a regular basis. Because of this, the odds were high that he would one day die in battle.

On his way home from the Third Crusade, Richard was taken prisoner in December 1192 by Duke Leopold V of Austria because of a grudge stemming from the siege of Acre. When Leopold, who took command of the German contingent after Frederick died, had placed his banner next to Richard’s on the battlements of the captured city, Richard’s troops tore down the banner and threw it into a ditch. They did this because they believed that the Germans had done little to contribute to the fall of the city. Whether Richard ordered them to take it down is not clear, but he did not tell them to put it back, either. From that point forward, Leopold considered Richard his sworn enemy.

Richard’s mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, paid her son’s ransom of 100,000 silver marks. Richard was freed in Mainz on February 4, 1193. Before sailing to England, he forged key alliances in the Rhineland, Flanders, and Holland that would pay handsome dividends in the future. Richard arrived at Sandwich in Kent on March 13. John’s intrigues against Richard came to nothing for his older brother retained the loyalty of his subjects.

In preparation for his journey to Normandy, Richard put in place a new land tax called a carucage in which the amount of tax owed was determined by the size of the estate owned by the taxpayer. In addition, the king and his chief justiciar, Hubert Walter, entered into various agreements with individuals and groups by which the party agreed to pay a fee in return for privilege or protection. After a crown-wearing ceremony on April 17 at Winchester Cathedral designed to show his subjects that he was in good health, Richard began assembling an expeditionary army for a long campaign in Normandy.

Richard was anxious to sail to France, for he knew that Philip had not only been seizing castles in eastern Normandy, but also in the Loire Valley. Elsewhere, rebel lords in the Duchy of Aquitaine also caused trouble for Richard. John had been Philip’s willing accomplice. Richard’s younger brother, who desired the English throne for himself, had ceded all of Normandy east of the Seine River, except for the capital of Rouen, to the King of France.

The Vexin region of Normandy was a source of continuing conflict between the Duke of Normandy and the French crown. Richard’s father, King Henry II, became the first Angevin monarch of England when he ascended to the throne in 1154. Two years earlier, Henry had wed Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the wealthiest women in Europe. Through his marriage and his inheritance, Henry ruled England, Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Touraine, and Aquitaine.

King Henry II had made substantial improvements to many of the castles in the Vexin to prevent their fall to Philip, who had ascended to the French throne in 1180. One castle in particular, Gisors, was coveted by both sides because it was situated in a key location on the Vexin’s eastern frontier. In 1193 Castellan Gilbert de Vascoeuil surrendered Gisors to Philip. Many of the nobles in the Vexin were torn between supporting Richard, who they believed might not return from captivity, and Philip, who put heavy pressure on them to join him. Some barons tried to have it both ways. Known as “cross-border nobles,” they tried to remain loyal to both the Duke of Normandy and the King of France, but it was a strategy fraught with peril should one or both of their sovereigns decide to punish them by taking their lands. Many had sided with Philip during Richard’s captivity on the grounds that if they did not submit to Philip they faced the loss of their lands and financial ruin.

Philip had taken possession of more than two dozen of the castles in the Vexin by the time Richard was ransomed. Some had been taken by storm, and others had simply lowered their drawbridge to avoid a siege. Philip had tried but failed to capture Rouen, the capital of Normandy, in February 1194.

Philip continued his aggression in the Vexin in May while Richard was bottled up in Portsmouth waiting for stormy weather in the English Channel to subside before embarking for the coast of Normandy. Philip’s target was Verneuil Castle in the southern Vexin.

After an absence of four years, Richard crossed the English Channel with a fleet of 100 ships laden with men, horses, and siege equipment. On March 20 he arrived at Barfleur where he was received with great fanfare by his Norman subjects.

Richard’s first stop was Lisieux where he met with the Count of Alençon. While at Lisieux, 27-year-old Prince John arrived to beg his older brother’s forgiveness. Richard magnanimously forgave his younger brother on the grounds that John had been deceived by enemies who pretended to be friends. “You have gotten into bad company, and it is those who have led you astray that will be punished,” said Richard. Count John became one of Richard’s subordinate commanders, although Richard had far more trustworthy commanders.

As a show of good faith to Richard, John marched against the stronghold of Evreux determined to claim it for Richard. Earlier that year, Philip had given John control of the town. John had the townspeople and garrison slaughtered and installed an English garrison in their place. The heavy-handed manner in which John behaved reflected his true nature. He lacked the diplomatic skills characteristic of great leaders.

Richard’s first objective was to relieve the garrison at Verneuil. For operations in Normandy and the Loire Valley, he could count not only on Anglo-Norman forces, but also on his Navarrese allies. Richard had married Princess Berengaria of Navarre in May 1191 in Cyprus during the Third Crusade. Eleanor of Aquitaine arranged the marriage largely to forge an alliance with Navarre that would protect Aquitaine’s southern border from foreign incursions. To assist Richard against Philip, King Sancho VI of Navarre sent an army into France.

The situation at Verneuil was dire, for Philip’s siege machines had already knocked down one wall of the fortress. Richard divided his army. He sent a small force of knights, crossbowmen, and infantry to break through the siege lines and reinforce the garrison. The forces entrusted with this objective achieved their mission. The rest of the army he sent on a raid to cut Philip’s supply lines. The day after the English reinforced the garrison, Philip raised the siege and departed. Richard chased the retreating French and captured their siege train.

Richard needed professional troops who were skilled and reliable. He set about building a quasi-standing army in which the recruits served for a one-year minimum. His army included English, Normans, Navarrese, Welsh, Genoese, and Brabanters. The Brabançons were an unruly lot who had no compulsion about slaughtering noncombatants when the occasion arose for brutality. Richard’s army included a number of veteran crusaders as well as a small number of Saracens.

After his return from Aquitaine in early summer, Richard began rolling back Philip’s gains in the Loire Valley. The English king captured and demolished Montmirail Castle on the Maine-Perche border. Afterward, he marched into Touraine where he successfully stormed Loches Castle on June 13, 1194.

Philip grew increasingly alarmed at the gains Richard was making in the Loire Valley, and so in early July he marched south from Paris to Freteval on the frontier of Anjou. Richard had anticipated the move, though, and had moved into a blocking position at Vendome. Philip, who was afraid he might lose a pitched battle with Richard, made a hasty retreat north on July 4. Richard once again gave chase, and this time he captured Philip’s baggage train.

The war did not always go in favor of Richard and his captains, however. When John and William d’Aubigny, Earl of Arundel, besieged Vaudreuil Castle in the Vexin, which the French had captured five months earlier, Philip rushed to save it. The French king fell upon the Anglo-Norman camp at dawn, achieving a much-needed victory.

Philip and Richard entered into a truce on July 23. The Truce of Tillieres set forth that the two sides were to refrain from hostilities until November 1, 1195. It was unlikely that the truce would last long owing to the chaotic local politics of the Norman Vexin, though.

Richard decided during the truce to win back key areas in southwestern France that he had surrendered to the French when he ascended to the throne in 1189. He led the Brabançons in a whirlwind march of conquest in mid-summer through the County of Berry. At the outset of the expedition, Richard captured Issoudon Castle. Situated on the upper Loire, it was a natural gateway to Touraine and Poitou. Then, Richard sent the Brabançons into the County of Auvergne where they secured several key fortresses and took the pro-French Count of Auvergne into their custody.

Philip marched against Issoudon Castle in mid-November. When Richard learned of Philip’s expedition, he rushed to the castle’s relief. When he arrived, he pierced the French siege lines and reinforced the garrison. More Angevin forces followed, and they encircled Philip’s small army. Philip had to agree to terms set by Richard before he was allowed to depart on December 5 with his army intact.

Philip and Richard held a peace conference in January 1196. The Peace of Louviers was an interim settlement. The terms of the agreement were favorable to Richard because by that time he had gained the upper hand. The agreement required Philip to acknowledge Richard’s gains in the Vexin, County of Berry, and Duchy of Aquitaine. In regard to Aquitaine, Philip was compelled to recognize that several rebellious counts were indeed Richard’s vassals.

Richard then prepared to assert his control over the Duchy of Brittany. In the spring of 1196 he summoned Duchess Constance of Brittany to attend his court with her son and heir, nine-year-old Arthur. Arthur, like Prince John, was a potential heir to the English throne.

Breton rebels intercepted and kidnapped Constance and Arthur while they were on their way through Normandy. Richard responded by invading Brittany, so the rebels took Arthur to Philip’s court to keep him out of Richard’s hands. Philip responded by granting asylum to Arthur. While Richard had tried to gain control of Brittany, Philip had been hard at work forging alliances with the counts of Boulogne, Flanders, and Ponthieu.

A large Franco-Flemish army subsequently attacked Aumale, a fief in the northeastern section of the Norman Vexin, in July 1196. Richard countered by capturing Nonancourt in the southern Vexin. Richard then tried to relieve Aumale but was unsuccessful. The Angevin garrison at Aumale surrendered on August 20, and Richard was forced to pay 3,000 marks to secure its release.

Richard had been thinking throughout the first half of 1196 of ways to get a decisive strategic advantage over Philip. One of his ideas was to entice both Count Baldwin of Flanders and Count Raymond VI of Toulouse to abandon their respective alliances with Philip.

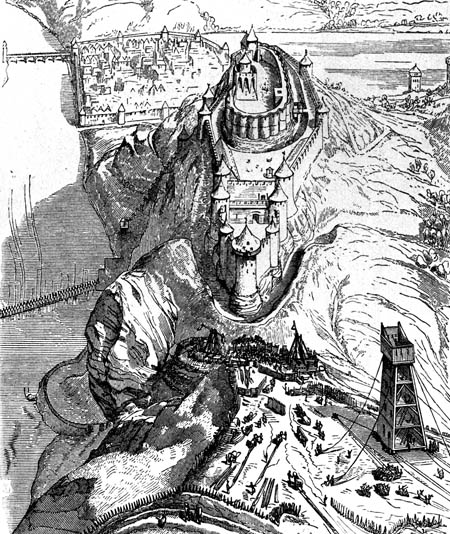

The other idea was to begin construction of a new castle on the Seine that would serve as a base camp for a concerted campaign to reconquer the remaining fortresses in the Vexin. The castle itself would be built upon the Rock of Andeli, a towering cliff overlooking the river. The castle would be the centerpiece of a fortified complex whose grounds would be large enough for an army to encamp.

He faced two political problems in regard to the site selection. First, the Treaty of Louviers signed in January 1196 by Philip and Richard forbade either one to fortify the site. Richard simply ignored this. Second, the Manor of Andeli was owned by Archbishop Walter of Rouen, one of Richard’s Anglo-Norman friends and supporters. Despite their friendship, the archbishop declined to give the land to Richard. The reason the archbishop refused the request was that he had established a tollhouse on an island in the river to collect dues from boats carrying cargo up and down the river. Because his archbishopric had suffered a decline in revenue as a result of the ongoing war, the archbishop badly needed the tolls derived from the river commerce.

Richard began construction of Chateau Gaillard despite the archbishop’s objectives. The archbishop subsequently departed for Rome to make a personal appeal to the Pope Celestine III. Before setting out on his journey, the archbishop placed an interdict banning all church services in the Duchy of Normandy as retaliation against Richard’s occupation of the manor.

Construction on the castle and the associated fortifications began that summer. In addition to the castle sited atop the 300-foot limestone promontory overlooking the river, Richard constructed a fortified town on the north side of the castle known as Petit-Andelys. A bridge connected Petit Andelys to the river island, and another bridge connected the island to the far bank. Richard had his laborers construct an outer wall on the opposite side of the river that enclosed the land inside a wide bend in the river.

Richard had considerable math, engineering, and design skills that made him a master builder. In addition, he had an extensive knowledge of siege warfare and incorporated not only contemporary concepts used in Western Europe, but also design features from the Christian and Muslim castles he had seen during the Third Crusade. The work on Chateau Gaillard was completed in just two years. Richard oversaw the process, and he allowed nothing to interrupt or delay it. The total cost of the project was 21,203 pounds sterling, and it amounted to three times what Richard spent on improvements to all of the castles in England during his reign.

The completed castle was an engineering marvel for its time. It incorporated existing rock into its design and had a three-tiered defense in depth to frustrate besiegers. The castle was protected to the west by the river and to the north and east by steep slopes. This left the south side as the only viable avenue of attack for a besieging army. The castle had an outer bailey, middle bailey, and inner bailey, each with protective stone walls and towers.

The triangular-shaped outer bailey was surrounded by a moat and featured one large circular tower and three smaller semicircular towers in walls that were 30 feet high and 12 feet thick. The only way to reach the middle bailey from the outer bailey was to cross a causeway laid out with a zigzag turn designed to thwart an attacker from rolling a siege engine from the outer bailey to the walls of the middle bailey.

The middle bailey, which housed a chapel overlooking the river, also had three semicircular towers, one on each corner facing the outer bailey and one on the front. The inner bailey, which was enclosed by the middle bailey, had a keep but no towers on its walls; however, its walls were 39 feet higher than those of the middle bailey. Like the outer bailey, the inner bailey also had its own moat with a bridge carved out of the natural stone.

Richard added a number of clever touches based on his observations of castles in the Holy Land. The base of the walls were buttressed to make it difficult for miners to dig through or under them and also so that obstacles dropped from machicolations above would ricochet off the buttresses and strike the attackers at the base of the walls. Additionally, the towers were rounded and placed close enough to each other to furnish covering fire and ensure that there was no dead space between them where an attacking force would have cover from defensive fire.

While the builders worked continuously throughout 1197 on Chateau Galliard, Richard forged alliances with Baldwin of Flanders and Raymond VI of Toulouse. Richard won over Count Baldwin by lifting an Angevin embargo on Flanders. He also gave him 5,000 marks and a large volume of wine from the fertile vineyards of Aquitaine. As for Count Raymond, Richard gave him his sister Joan’s hand in marriage, renounced his ducal claims to Toulouse, and restored the disputed Quercy region to the Count of Toulouse.

In 1197, Baldwin attacked the French-held region of Artois while Richard attacked the remaining French strongholds in the County of Berry. This stretched Philip’s resources and forced him to fight a two-front war. The King of France moved against Baldwin for the attack on Artois threatened neighboring French royal lands. Baldwin fought a brilliant campaign. He lured Philip into chasing him by conducting a feigned retreat. When Philip gave pursuit, Baldwin sent forces west to surround Philip’s army. In the meantime, Richard captured 10 French-held castles in Berry. In September 1197, Philip and Richard agreed to another truce, which was scheduled to be in effect until January 1199.

Truces were routinely ignored, though. Philip found himself under attack in the autumn of 1198 by both Richard and Baldwin. The Count of Flanders invaded St. Omer. The people of the region appealed to Philip for relief; however, Philip could do little to help them because he was preoccupied with the defense of his fortresses in the Vexin.

After Chateau Gaillard was completed in 1198, Richard immediately set out to capture Philip’s remaining strongholds in the Vexin. He captured Vernon, Neufmarche, Gamaches, Courcelles, Boury, Serifontaine, and Dangu. Having a large base camp at Chateau Gaillard was paying handsome dividends.

In response to Richard’s completion of Chateau Gaillard, Philip reinforced the strongholds of Gisors and Le Goulet. A memorable incident occurred in late September 1198 when Richard’s troops surprised Philip’s army while it was on patrol. Finding his force outnumbered, Philip made for the safety of Gisors. When French knights and foot soldiers swarmed onto the drawbridge in an effort to escape the English, it collapsed, sending them into the moat. Philip, who was among those wo fell into the moat, very nearly drowned.

At that point in the war, Richard held the majority of the castles in the Vexin. A few of the strongest castles in the French Vexin remained in Philip’s hands largely because Richard lacked the siege equipment needed to capture them.

In December 1198, papal legate Peter of Capua arrived to negotiate a peace between the two rivals. Pope Innocent III wanted the two warring kings to put an end to the war so that they could support a new crusade that Innocent was preaching. Richard did not think much of the idea since he had encountered difficulties with the Church of Rome while conducting the Third Crusade. After berating Peter of Capua, Richard set off for Aquitaine in early 1199. He had a score to settle with the Count of Angouleme and the Viscount of Limoges, two steadfast supporters of Philip in Aquitaine.

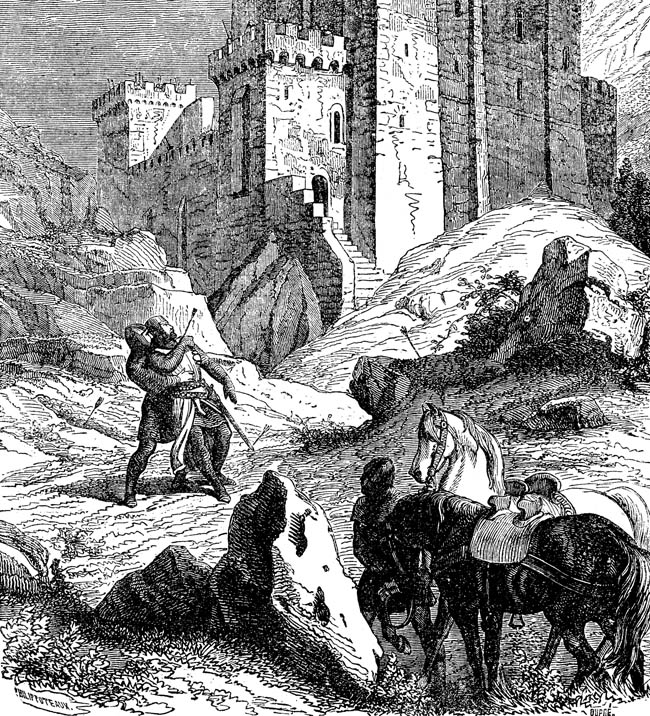

Richard was an unconventional warrior. Rather than fight only during the warm months as was established custom, he waged war throughout the year. He carefully prepared a campaign against these two enemies. In March 1199 Richard besieged Chalus-Chabrol, the viscount’s castle. On the third day of the siege, Richard was walking along the siege lines exhorting his sappers to hurry with their mining of the castle walls. His archers maintained a steady fire designed to keep crossbowmen on the battlements pinned down, but one in particular could not be suppressed. This intrepid crossbowman used a frying pan as a shield whenever he exposed himself to fire. He succeeded in firing a bolt that struck Richard in the shoulder. Richard quietly retired to his tent where he tried to extract the long iron barb himself. A surgeon eventually cut it out. The wound turned gangrenous, though, and Richard died on April 7.

Richard’s untimely death enabled Philip to move in strength against the Angevin territories in France that he had so long coveted. King John, who succeeded Richard, lacked the firm resolve and broad skills that Richard had possessed in warfare. In the coming conflict, Philip would rely on force of arms and feudal law to defeat John.

The following year Philip invaded Maine. At the outbreak of the war, John was in Normandy. John faced serious problems defending Normandy for many of its fortresses were in a state of disrepair and morale was low.

John had very few supporters in the counties of Maine, Anjou, and Touraine. For that reason, it was easy for Philip to conquer them. As for the approximately 50 lords in Poitou, they desired independence from John. To assert their independence, the Angevin counties denounced John in favor of young Arthur, who by that time held the title Duke of Brittany. Philip demanded that John turn over the three counties to Arthur and possession of the disputed Norman Vexin region.

It was absolutely essential that John retain Anjou and Maine if he wanted to retain his continental fiefs. Many of the principal roads in western France passed through these regions, and if he lost control of them he would no longer have a clear route north to Brittany and Normandy from Aquitaine. Of particular importance was the stretch of road connecting the towns of Angers and Tours that roughly paralleled the Loire River.

Philip led an army into Maine and seized and razed Ballon Castle. Philip and John signed the Treaty of Goulet in May 1200. For King John, the treaty ensured that the Angevin Empire remained intact and made Arthur his vassal. In exchange, John acknowledged that the counts of Flanders and Boulogne were French vassals. Additionally, John gave Philip 20,000 marks sterling as receipt of various lands and for his overlordship of Brittany.

When a marriage between 12-year-old Isabella of Angouleme and Hugh IX de Lusignan, Count of La Marche, threatened to strengthen the ties of powerful families in west-central France that could impede Angevin interests in Poitou and Aquitaine, John married the young heiress on August 24, 1200. Isabella had been engaged at the time to Hugh, and the Lusignan family was highly aggrieved by John’s move. Although John might have offered them compensation and assuaged their wounded pride, he made no effort to do so.

At that juncture, the Lusignans turned to King Philip for a remedy. John made matters worse by insulting the Lusignans. As if that were not bad enough, in 1201 John invaded the County of La Marche and the Norman County of Eu, which was held by Raoul, Hugh’s brother. The Lusignans redoubled their pleas for redress to the French king.

In his position as Duke of Aquitaine, John was Philip’s vassal. Philip summoned the duke to appear before him. When John failed to appear, the French royal ruled on April 28, 1202, that John was to forfeit all of his continental fiefs and embarked on a campaign to secure them by force. Chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall wrote that John and his predecessors “had long neglected to render all of the services due from the lands and had nearly always disobeyed the summonses of their lord and king.”

Following the French court’s ruling, Philip plotted a two-pronged attack in the summer of 1202 on the Angevin lands. An expert at siege warfare, Philip intended to systematically roll up the Angevin-held Norman castles east of the Seine while Arthur led a Breton army, reinforced by the Lusignans, in a march of conquest north of the Loire River to secure Anjou, Maine, and Touraine.

Philip knighted the young prince at Gournay in Normandy in July. Before Arthur departed, Philip warned the young warrior to be cautious, but Arthur’s enthusiasm for the upcoming campaign was boundless. Philip sent him off to Angers with a core of 200 knights and funds to raise more troops.

Arthur rendezvoused with Poitevin Baron Savery de Mauleon, Hugh and Geoffrey de Lusignan, and various other anti-Angevin barons. He then marched against Mirebeau Castle, which was situated between the towns of Angers and Poitiers, to capture his grandmother, Eleanor of Aquitaine. He intended to use her as a bargaining chip in negotiations with John. Arthur’s army arrived on August 1 but soon found it would take more time than he initially thought to compel the garrison to surrender.

William de Roches, Seneschal of Anjou, urged the English king to launch a surprise attack on the French besieging Mirebeau. John responded enthusiastically and marched south from Le Mans in late July. The surprise attack on August 1 was a great success. The English scattered the Breton army; in the process, John captured Arthur, de Mauleon, the Lusignans, and the other prominent barons.

John sent Arthur to Falaise Castle in Normandy. He was never seen again, and it is believed that John ordered his murder. John singled out the Lusignans for harsh treatment ordering them confined in chains until they were ransomed.

King John’s erratic behavior so alienated de Roches that he changed sides and John replaced him with one of his cronies. When word spread of the English king’s capriciousness, many of the lords on both sides of the Loire quit his service. Some tried to remain independent, while others gladly joined with Philip.

With Arthur’s vassals defending his interests in the Loire Valley, in the spring of 1203 Philip focused his attention on the conquest of Normandy. Philip’s ultimate objective was the capture of the late King Richard’s seemingly impregnable Chateau Gaillard.

Englishman Robert de Lacy, Constable of Cheshire, was John’s castellan at Chateau Gaillard. Before he could besiege the chateau, Philip had to reduce a number of lesser satellite castles in order to isolate the main prize. He began his march on the west bank of the river. Some of the barons willingly capitulated, sparing Philip a siege. This was the case with the castles of Montfort-sur-Risle and Beaumont-le-Roger. The most important supporting stronghold for Chateau Gaillard was La Vaudreuil. Philip braced himself for a protracted siege, but to his surprise the Norman castellan raised the drawbridge for the French troops.

Philip besieged Chateau Gaillard in September 1203. His first step was to construct a circumvallation ditch fortified with 14 towers to isolate the garrison. In an effort to make operations difficult for the attackers, De Lacy ordered the bridge over the Seine destroyed so that the French could not transfer supplies and siege equipment across the river. Philip responded by constructing a pontoon bridge.

Two English relief forces, one moving upstream on the Seine and the other marching overland, failed in their efforts to force Philip to raise the siege that autumn. In the hope of drawing off Philip, John launched a chevauchee into Brittany. But that ploy failed, too.

As the siege progressed, the French bombarded the walls of the outer bailey with trebuchets and constructed siege towers, known as belfries, to reach the top of the walls and a covered way to protect sappers. The French had to level the land on the south side of the castle in some places so that their troops could roll the belfries up to the walls.

The residents of Petit Andelys had taken refuge in the fort before the siege began. In an effort to preserve his supplies, De Lacy ordered them out of the fort. At first Philip allowed them to pass through his lines, but he eventually stopped allowing them to leave. This left several hundred poor souls trapped between the lines. They were exposed to missile and artillery fire as the siege continued. Philip eventually relented and allowed the starving noncombatants to depart.

The French not only tried to breach the walls of the outer bailey with a direct assault using troops in belfries, but also employed skilled miners to try to collapse them by setting fire to the wooden props holding back the earth in the tunnels. The latter was a particularly successful technique provided that a fort was not constructed atop solid rock as were some in the Holy Land.

In February 1204 the French succeeded in breaching the outer bailey as a result of a successful mining operation. Sappers tunneled under the wall and then fired the props that held up the tunnels. A portion of the wall collapsed, and the French fought their way through the breach.

Yet the miners were unable to dig beneath the foundation of the walls enclosing the middle bailey because they could not reach the lowest foundation. A lucky break came when a French soldier noted that a latrine emptied beneath the chapel on the west side. He scaled the path and from there entered the chapel through an unbarred window. A small number of soldiers followed him. Once inside the chapel, they made as much noise as possible to deceive the defenders into thinking that a large force had forced its way into the building. An effort to smoke out the assault party failed. A coordinated attack at the main gate to the middle bailey unnerved the defenders of the middle bailey, who were forced to fight both on their front and flank, so they decided to withdraw to the inner bailey.

The assault party in the chapel then opened the gate to the middle bailey for their fellow soldiers. The reinforced base of the walls enclosing the inner bailey thwarted attempts to mine them, so Philip ordered his trebuchets to batter the high stone walls. While the trebuchets pounded the walls, the miners found that they could tunnel into the wall under the stone bridge. The defenders dug a counter tunnel, hoping to frighten the French sappers, but the combination of two tunnels so weakened that section of the wall that sections began to fall off. When a wide enough breach opened, the attackers swarmed through it. The surviving 20 knights and 120 men-at-arms tried to escape on March 6, 1204, but were discovered and forced to surrender.

Philip then set about systematically conquering Normandy. Taking great pains to avoid a costly and time-consuming siege of Rouen, he began by conquering Lower Normandy. He reduced the main pockets of resistance in that region by capturing Argentan, Falaise, Caen, and Cherbourg. He then besieged Rouen. Unable to come to its relief, John authorized its surrender. Philip took possession of Rouen on June 24, 1204. He ordered the Norman keep torn down and in its place erected a circular donjon. From that point forward, Normandy was a province of France.

John also was unable to prevent the loss of the rest of his Angevin territories. When Arthur had paid homage to Philip two years earlier, the French king had just cause to take possession of Anjou, Maine, and Touraine. The decision by a coalition of 10 of the most powerful barons of the region to pay homage to Philip further strengthened the French king’s position relative to the Angevin lands. Guilluame des Roches, who was the seneschal of the three counties, switched to Philip’s side and secured the principal English garrisons in the region for Philip.

Philip’s campaign of conquest against King John of England from 1199 to 1204 proved that Philip was a master strategist, a skilled practitioner of siege warfare, and a firm and resolute monarch. The siege of Chateau Gaillard was a high point in the French conquest of the Angevin lands and stands as one of the most famous sieges in Medieval Europe.