By Blaine Taylor

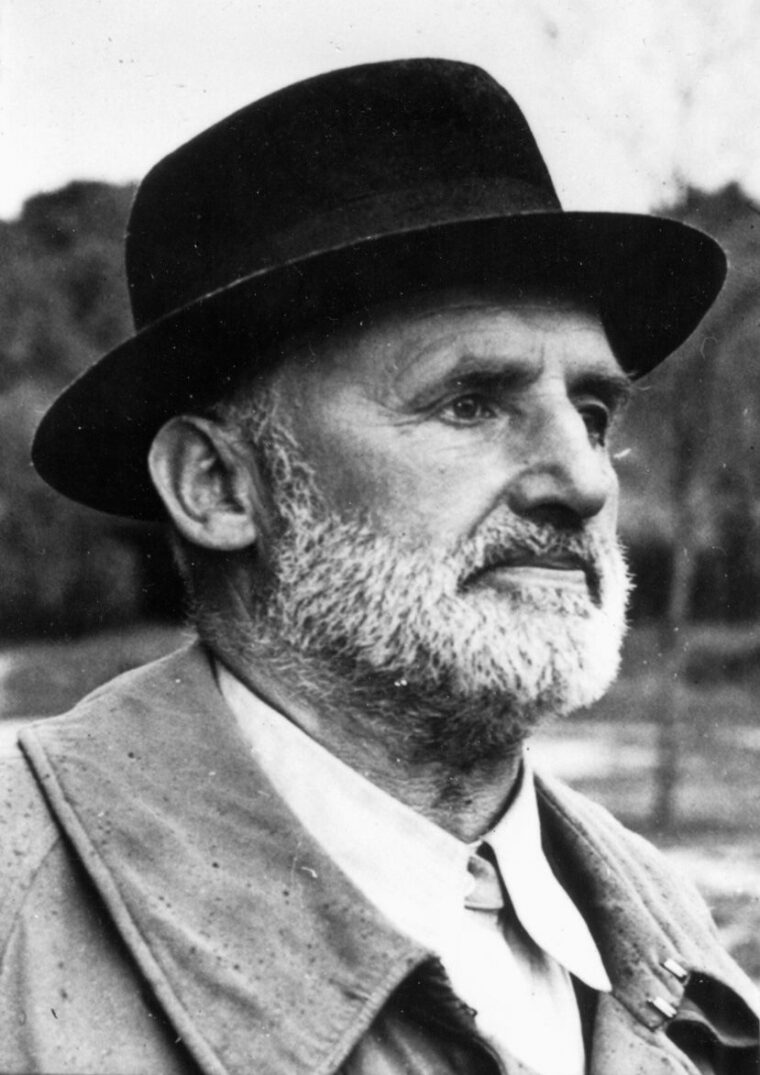

It was May 23, 1945, roughly a year before the execution of Julius Streicher, founder and publisher of the vilest anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda of the war. A jeepload of American GIs of the 101st Airborne Division, commanded by Major Henry Blitt, pulled up in front of a Bavarian farmhouse near Berchtesgaden for a drink of milk. Speaking Yiddish, the Jewish-American major began a conversation with a bearded man whom he mistook for the farmer, addressing him as “papa.”

The man insisted that he was an artist and understood nothing about either politics or the just defeated Nazis, leading Major Blitt to declare, “But you look like Julius Streicher,” whose warrant mug shot he had just seen. Startled, the “painter” blurted out, “How did you recognize me?” and thus it came to pass that the 59-year-old man with the shaggy beard, uncombed hair, blue striped shirt, and ragged trousers was arrested for being the accused notorious Nazi war criminal that he actually was. Ironically, the world’s most infamous Jew baiter had himself been found out by a Jew.

Streicher, a former schoolteacher and holder of the coveted Iron Cross for his service in the German Army in World War I, was also an honorary Nazi SA Storm Troop leader and former Gauleiter (regional leader) of Nuremberg and Franconia, as well as an elected member of the national Reichstag in Berlin.

He had been the all-powerful boss of Nuremberg, site of the massive Nazi Party congresses of 1927-1939, until he angered Adolf Hitler’s number two man, Hermann Göring, in 1940 by suggesting that the latter’s daughter was a test tube baby and not fathered by the “Iron Man” at all. Enraged, Göring insisted that Streicher be fired, and Hitler banished him from his high posts for the rest of World War II.

Julius Streicher: “Dirty Old Man” of the Prison

In the Allied prison at Nuremberg after the war, Streicher also soon established himself as the third most controversial prisoner, after Göring and Rudolf Hess, for his jailhouse antics. When the prison physicians asked him to undress for the standard physical examination, a female Russian interpreter stepped to the door and looked away, leading a leering Streicher to ask, “What’s the matter? Are you afraid of seeing something nice?” Disgusted, the girl shivered in revulsion and remained turned away from him.

Nor was she the only one at Nuremberg to turn her back on the man who allegedly washed his face in his sparse cell’s toilet bowl, the so-called “dirty old man” of the prison. Indeed, almost all of his fellow accused war criminals considered Streicher unfit to socialize with. He also rated the lowest on the prison-administered intelligence quotient tests, and even his own defense counsel wondered whether his lewd sexual perversions and rabid anti-Semitic writings and speeches did not in fact spring from a diseased mind.

The official psychiatric conclusion, however, was that, although he suffered from a neurotic obsession, he was not clinically insane and therefore was both mentally and legally competent to stand trial for his life. The guards despised him for calling out lewd remarks in the prison whenever a woman appeared, while his fellow Nazis recalled with disgust when, during his days in power, Streicher strutted about Nuremberg, whip in hand, lashing out at Jews and others and openly trying to seduce German women as well.

Former German finance minister and Reichsbank president Dr. Hjalmar Schacht told one of the prison doctors, “You just have to look at that worm Streicher on the stand and see the kind of man Hitler protected to the very end! Ugh! That man Hitler had no conception of decency and honor and dignity. He kept the criminal scum in power.”

The Self-Described “Fate-Ordained Apostle” of Anti-Semitism Responsible for Der Sturmer

Oddly, Streicher began his Nuremberg defense from the dock of the accused by denouncing his own attorney for not conducting his case along the lines that the defendant wanted.

He then launched into a self-defeating, bombastic oration, describing himself as the “fate-ordained apostle” of anti-Semitism. He said that when he first met Hitler, he envisioned the latter with a halo encircling his head. As the judges listened quizzically, his fellow defendants in the dock sat in embarrassed silence. Göring buried his head in his hands as if he were sick, while former grand admiral Karl Donitz shook his head. Alone among them, former interior minister Dr. Wilhelm Frick thought that Streicher had spoken well.

Aside from hurting his case by orations such as this, Streicher was also convicted by his own writings in his former newspaper Der Sturmer (The Stormer), in which his anti-Jewish opinions were given full-scale publication for all 12 years of the Third Reich, read and approved by Hitler himself.

The paper featured crude but vivid anti-Jewish cartoons, photographs, and articles that have been viewed as the very nadir of Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda ever since. They formed the basis of the hate that later, in the view of the International Military Tribunal’s justices, underlaid the gassings of 1941-1945. The world’s media, though, dubbed Julius Streicher “the high priest of stupidity.”

Both within the Third Reich and in the dock before his accusers, however, Streicher proudly accepted full responsibility for everything that appeared within Der Sturmer’s pages, including the special issues that were devoted entirely to alleged Hebraic ritual murders.

A Common Denial of Knowledge of the Holocaust

During the daily trial lunch breaks, Streicher’s fellow defendants soon discontinued even discussing him and his case as they considered the topics beneath contempt and believed they gave all the rest of them a bad name. There was, however, at least one domain in which they all made common cause, and that was in their full denial of anything even remotely having to do with Hitler’s Holocaust against the Jews, Gypsies, and other Nazi racial undesirables.

For his part, Streicher repeatedly said that even if he had read those things, he would not have believed them. He had spoken like Hitler about exterminating the Jews but had not meant it literally, he claimed.

Indeed, when the infamous atrocity film was shown to the court on November 2, 1945, Streicher watched it, immobile except for an occasional squint, while another in the dock recoiled and later asserted, “I don’t believe that. Perhaps in the last days.…” Sitting alone in Cell No. 25, Streicher called the film “terrible” without any feeling and asked the guards if they could not be quiet at night so that he could sleep.

The prosecution, however, quoted in open court Streicher’s own words of 1925: “Let us make a new beginning today, so that we can annihilate the Jews!” Speaking to one of the prison psychiatrists on July 13, 1946, Streicher did admit, “There was no doubt that Hitler had ordered the extermination of the Jews, and had, as a matter of fact, expressed that intention before the war. Early in the war, he must have realized that he would have to die and decided to take the Jews with him. But that was no solution, because you would have to exterminate all the Jews, and there are still many Jews in all countries, so Hitler’s idea of exterminating the whole race was obviously impractical.”

The prosecution indicted Streicher for having preached the central ideology of the Nazi movement, the one article of faith that all the others really agreed on, namely that the Jews had been the main cause of the loss of World War I, and of the subsequent economic disaster that had befallen defeated Weimar Germany.

The Making of a Gauleiter

Who was Julius Streicher? Born on February 12, 1885, he was one of nine children in the family of a Swabian schoolteacher, the same locale that had produced Erwin Rommel. In the Great War, Streicher, too, was an infantry lieutenant and, like Hitler, served in the Bavarian Army, where, also like his future Führer, he was awarded both the first and second class of the Iron Cross. Following the lost war, Lieutenant Streicher returned to his own chosen profession of teaching in an elementary school.

By the time he became one of the first to join the embryonic Nazi Party, Streicher also had his own small band of anti-Jewish followers, all of which he brought with him into Hitler’s thin ranks, a boon that his Führer never forgot. Streicher began his political career as a German left-wing socialist and then moved to the right, into the ranks of the Nazi labor movement that believed that the Jew was the ultimate symbol of rapacious German capitalism.

Streicher founded his own splinter party in 1920 that was based entirely on anti-Semitism and presented it as a gift to Hitler the following year. His extracurricular political activities got Streicher into hot water in his daily role as a schoolteacher, however, as he required the children in his classes to greet him with “Heil Hitler!” Before that salutation became mandated legally, he alienated his fellow teachers by accusing them of being anti-German and angered his superiors by taking sick leave to attend Nazi rallies.

On November 9, 1923, Streicher spoke to Munich street crowds during Hitler’s abortive Beer Hall Putsch and marched with Hitler and Göring into the hail of police gunfire that ended it. In 1925, a grateful Führer named Streicher as a Nazi Gauleiter.

In 1928, the school commission brought charges against Streicher in the form of an 87-page report. Found guilty of conduct unbecoming a teacher, Streicher was fired from his post.

Surviving the War, But Not the Trial

After Hitler was named to the chancellorship in 1933, there was, reportedly, virtually no limit to Streicher’s importance in his home district of Franconia, despite his many party enemies in both Munich and Berlin.

When asked at Nuremberg why Hitler backed both his continued publishing of Der Sturmer and his political standing within the Nazi Party, Streicher replied, “Oh, well, you know that I marched in the front rank with him in the Munich putsch, and he never forgot that, and I remained faithful, too, while he was in prison. Even after I was kicked out [in 1940], he sent Goebbels and [Dr. Robert] Ley to visit me a couple of years ago to ask if I desired anything. So I told them [with a dramatic gesture], ‘Tell my Führer that I desire nothing except to die beside him in case a catastrophe should befall the Fatherland!’” Streicher held the pose for a moment and then added, “And that impressed him no end.”

In 1945, however, Streicher went into hiding instead. Once accused in the German civil courts of rape, defendant Streicher was also sued several times for libel before the Nazis took office, and he also had to pay small amounts for damages. Sometimes, he was even sentenced to jail for a few days’ duration.

In 1933, Streicher began taking his revenge on the Jews, even personally setting in motion the crane that destroyed Nuremberg’s main Jewish synagogue. He was also a notorious thief of Jewish money and seized properties to benefit himself, not the party, and by 1940, these corrupt expropriations had reached such a level that Göring chaired a commission of investigation.

The immediate result was that Göring was able to return 63,938.92 reichsmarks to the vaults of the Reich, and it also emerged that Streicher had been a tax evader. Fired from his post as Gauleiter, Streicher was still permitted, however, to retain his editorial position at Der Sturmer until war’s end.

It was not until he came before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and was convicted of “crimes against humanity” that he was threatened with death by hanging. That one count cost Streicher his life. Nazi radio producer Hans Fritzsche noted, “Well, they’ve put a rope around his neck after all.”

A Justified Execution?

In 1991, the late Nuremberg jurist and author General Telford Taylor gave as his reconsidered opinion that Streicher had, perhaps, been unjustly convicted and hanged for his writing alone. British writer Hilary Gaskins, quoting lawyer Daniel Margolies, said, “They had some problems with Streicher … He did write terrible stuff, but you don’t normally hang people for that. They scrounged around and found that he had killed somebody … Somehow, nobody wanted to acquit him.”

Oddly, Streicher in 1945 was said to have boasted that he had his political rival, Nuremberg mayor and fellow Nazi Willy Liebel, murdered during the last days of the regime. Mayor Liebel had also been a deputy to Hitler’s armaments minister, Dr. Albert Speer.

Just prior to his execution by hanging on October 16, 1946, Streicher stated in his cell that he actually admired the Jews for fighting, resisting, and sticking together: “Even if Hitler was living now, he would also admit that they are a spunky race. I would be ready to join them now in their fight! No, I am not joking!”

Did anyone have a kind word to say for Julius Streicher? His first wife, Kunigunde Roth, a brewer’s daughter whom he married in 1913 and who bore him two sons, died in 1943. Early in 1945, Streicher married again, this time to his secretary, Adele Tappe, so that they could die together in Nuremberg in a projected last-ditch defense of the city in which they did not take part after all.

Adele’s visits to the prison during 1945-1946 created a sensation, as everyone wanted to see what kind of woman would marry Julius Streicher. She testified on his behalf that he was a nice man, but the Allied prosecutors did not bother to cross-examine her.

Blaine Taylor is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has written numerous books and resides in Towson, Maryland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments