By Marcus Brotherton

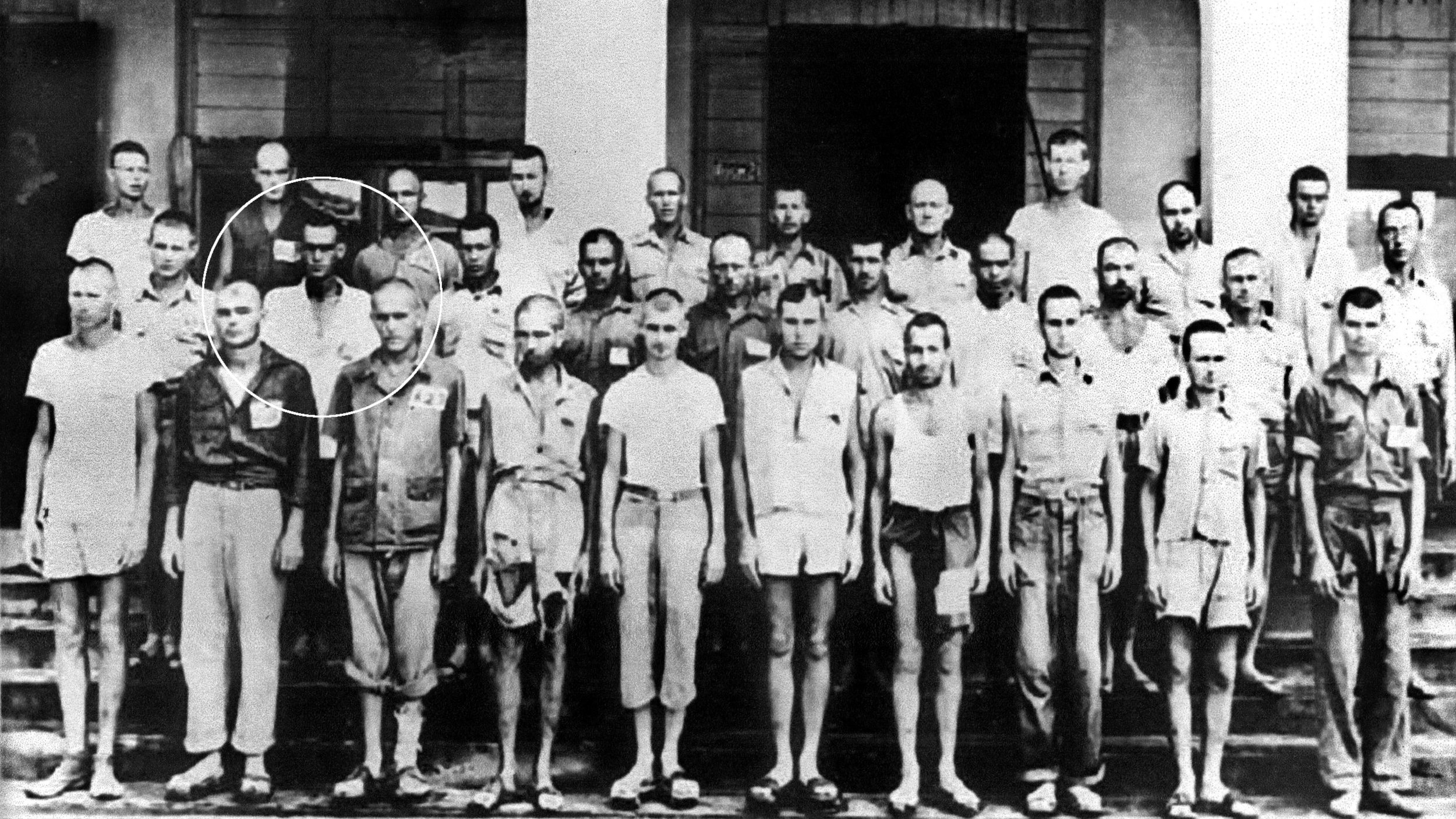

Private Joe Johnson wakes on the floor of the Pasay schoolhouse, a few miles south of downtown Manila, capital of the Philippines. He sits upright, rubs his eyes, and peers through the gloom. It’s spring 1943, and Joe checks his canteen, mess kit bowl, and spoon to make sure they haven’t been stolen during the night. Besides the clothes on his back, they are his only possessions.

Joe knows he ought to lie down and try for more rest before the wake-up order is given, but he wills himself to stay sitting. The daylight has almost come. Across from him in the schoolroom is a chalkboard covered with Japanese words scrawled phonetically with English letters. Joe squints and looks closer as the light grows. If any prisoner believes he has learned a phrase, he writes it on the board for the others to learn. Hurry up. Come here. Lift this. Carry that. The more of the Japanese language a prisoner knows, the fewer times he is hit.

Joe studies the board for a few minutes, grabs his mess kit and canteen, pockets his spoon, and trots outside toward the latrine. He looks both ways then carefully closes the door behind him. In any spare moments, Joe grinds his spoon against a stone in the latrine, sharpening the handle to a razor’s edge. He likes the idea of carrying a hidden weapon.

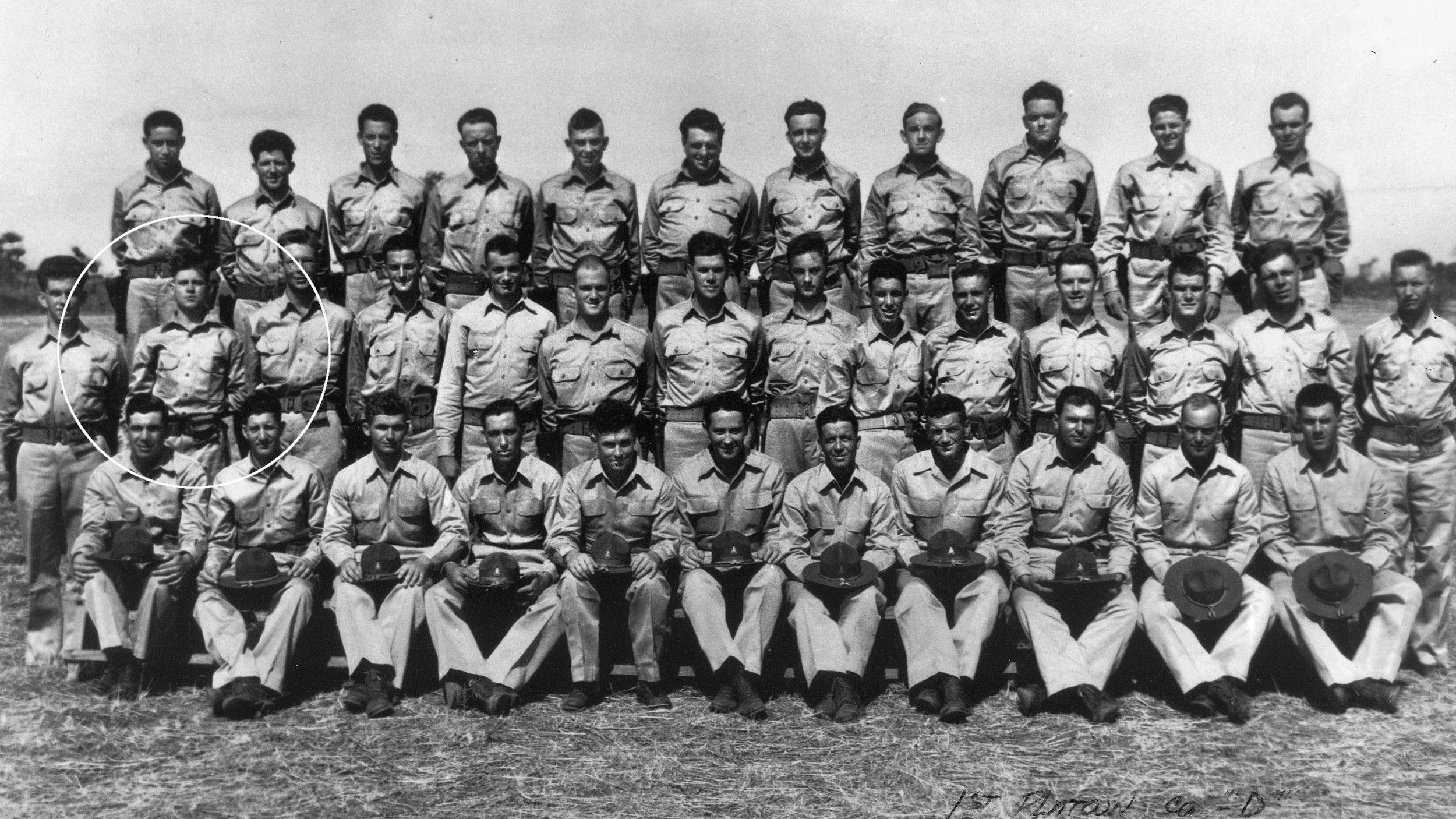

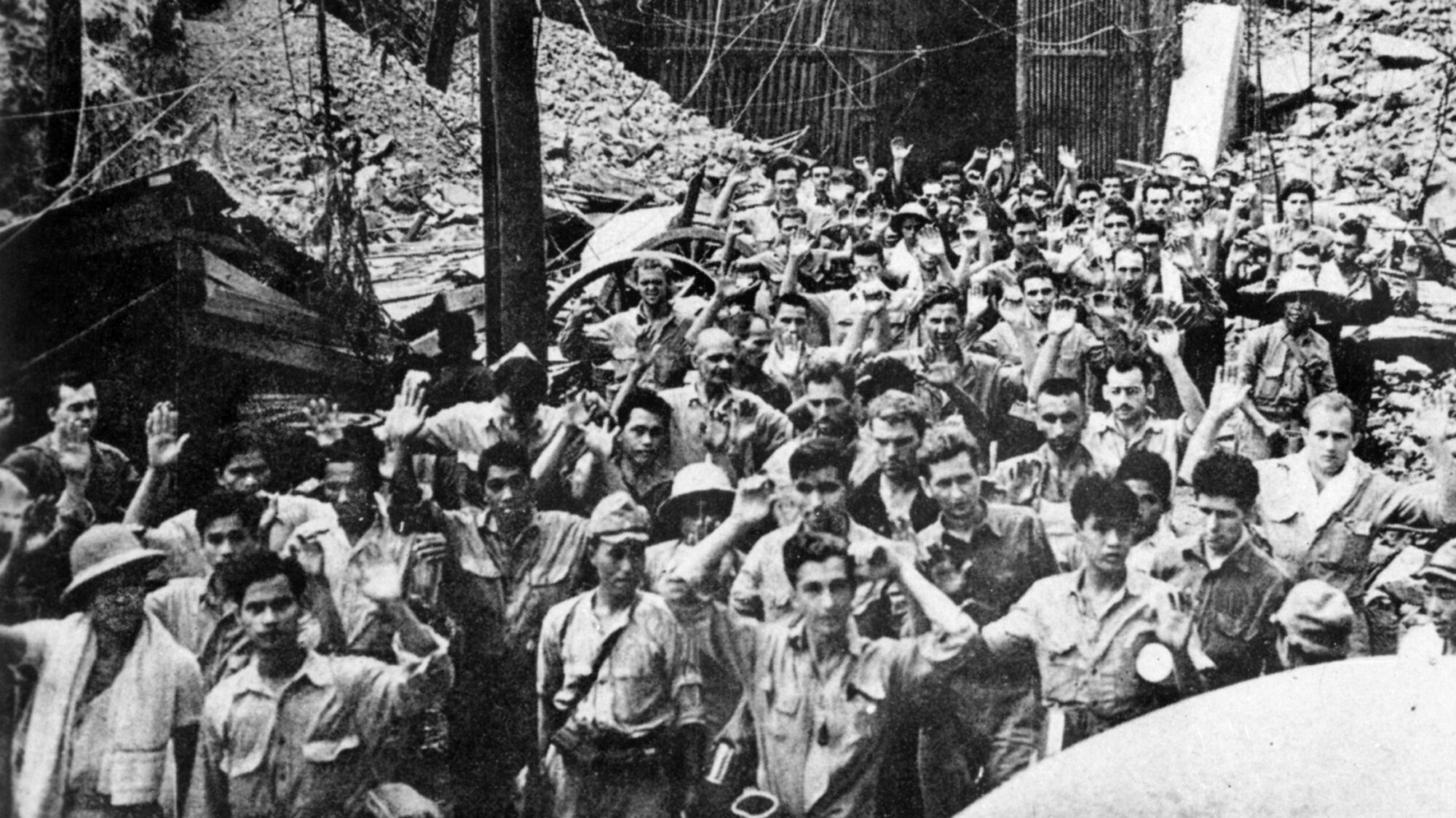

He shouldn’t have been in the Army to begin with. At age 14, a year before Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Joe had run away from home and fibbed about his age to enlist, claiming he was 18. After being sent to the Philippines, he’d served as a bugler until the Japanese invasion. He’d picked up his rifle and fought on Bataan until its surrender on April 9, 1942, then fought on Corregidor until it fell a month later. Outgunned, outmanned, starving, and disease-ridden, the U.S. troops had few options. At last, General Jonathan Wainwright had raised the white flag. Young Joe Johnson became part of the largest group of U.S. troops ever to surrender.

Now, a year into his stint as a prisoner-of-war, Joe has just turned 17. As he eats a meager bowl of morning rice, he reminds himself to keep a sharp lookout during the day ahead. The prisoners are counted and marched from the schoolhouse to the Nichols Field worksite, a 45-minute trek by foot. The enemy is forcing POWs to extend an airstrip by hand. It will become the longest runway in the Pacific. Joe is handed a pickax and ordered to work.

Prisoners are already hacking into a ridge to his right, ripping away at the rocks and dirt with pickaxes. More prisoners shovel the debris into railway carts, while others lug the loads to a destination he can’t see. Sweat runs across bone and sinew. Every man is a scarecrow.

A young prisoner off to the left has angered the guards. The work slows slightly as the others watch in short, furtive glances. Guards surround the prisoner. It’s barely noon, and a guard nicknamed El Lobo beats the man across the back with his cane. Another guard strikes him hard across the mouth.

It’s not the first beating that Joe has witnessed at Nichols Field. Most beatings don’t last long, but some are known to stretch through the afternoon if the guards feel so inclined. For this man, the guards stop the beating and make him dig a hole. Joe knows this can’t be good. The prisoner is tired and cut up, yet all afternoon he is forced to dig until it’s late in the day.

Near sunset, the commandant appears and strides over to the prisoner. He’s dug his own grave. As the soft diffusion of twilight descends over the field, the commandant beheads the man. Joe’s stomach lurches but he has no choice but to continue working until the order is given to stop. Joe has no boots.

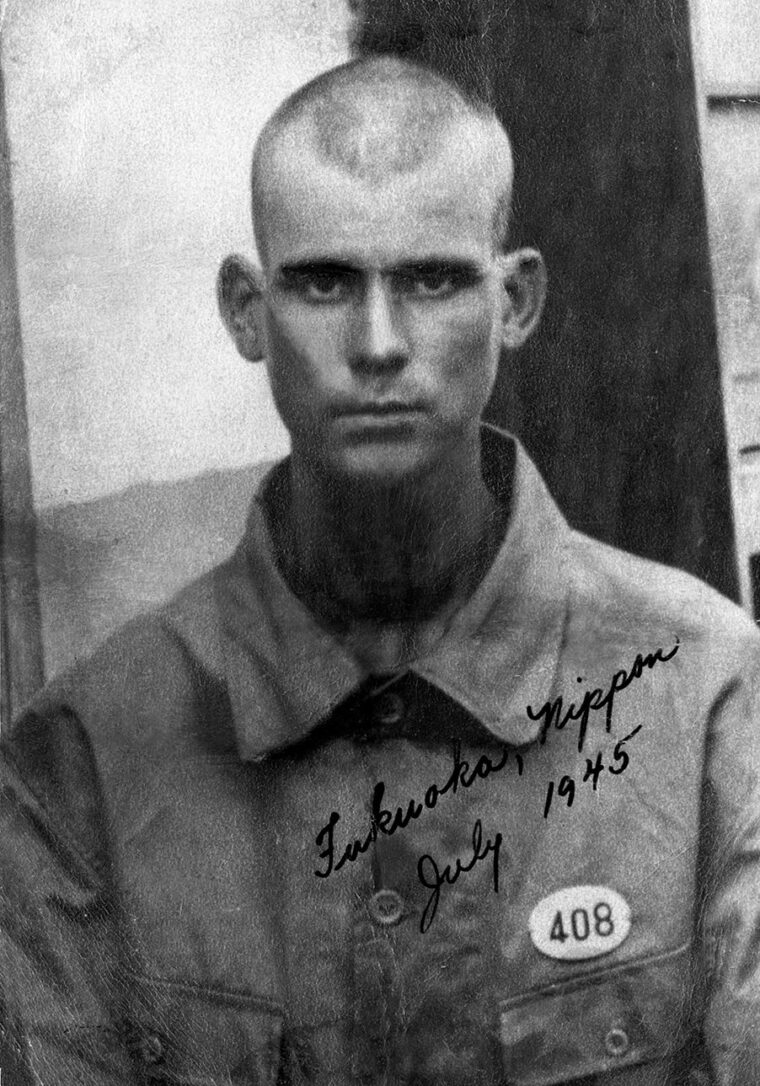

They rotted away in the rainy season. He has scaly sores on his legs and ankles. He runs a constant fever—his body sometimes burning, sometimes freezing—and he often shakes throughout the night. He’s lost some of the feeling in his hands and feet. The membranes of his mouth and nose are inflamed. His gums are bleeding and swollen. His stomach hurts continually. He’s grown to over six feet tall but weighs less than 110 pounds.

One of the rooms at Pasay is a small infirmary, and a medic has diagnosed him with dry beriberi, pellagra, scurvy, and a persistent case of malaria. The hard labor and starvation diet intensify the mix of ailments that steadily beat him down.

A season passes, and when summer 1943 arrives, the commandant raises the pressure. He wants the runway completed soon. Quotas are upped. Beatings become more frequent. One prisoner is shot without provocation. Another is beheaded. Several try to escape but are caught and executed. Joe notes the heightened irritability of the guards and vows to keep his head down.

But late one afternoon Joe’s luck runs out. His crew is sluggish. The men are exhausted. Joe tries to rally the men. He picks up the slack on behalf of the others.

But El Lobo strides over to check things out.

“Speedo!” El Lobo shouts to the men. It’s the one English word all guards seem to know. He clubs the closest with his cane. It’s Joe. El Lobo shouts again. Again Joe is hit.

“Can’t you see we’re trying,” Joe mutters, his eyes focused on his work. El Lobo snorts and clubs Joe a third time.

The burning fuse reaches the dynamite. Explodes. On reflex, the boy snatches the cane out of the hands of El Lobo and breaks it across his knee. The moment the broken cane clatters on the gravel beneath his feet, Joe realizes he is dead.

El Lobo yells for support. Two guards run over and grab Joe. The other prisoners in Joe’s crew glance in his direction and shake their heads. The guards hustle Joe to a guardhouse at the main entrance of the work area. They order the boy to stand at attention while they take turns hitting him in the ribs with their rifle butts. Another guard runs over and joins the fray. They hit his face. Shoulders. Arms. The side of his head. Kick him in the crotch. They shout in Japanese: “Why did you break the cane? Tell us! Why?”

Joe refuses to answer. Silence is his final dignity.

An American officer, a fellow prisoner, sizes up the situation and sprints over. He bows to the guards then shouts at Joe to answer his captors. “Tell them something. Anything! You can’t just stand with your mouth shut when they’re asking you questions.”

The guards interpret Joe’s refusal to answer as defiance. Joe knows this but doesn’t care. He’s hungry. Sick. Worn out. Furious. He tries to spit at the guards, but his mouth is so dry nothing emerges. Blood runs from one ear and marks a red trail down his face. His nose is bleeding all over his chin. One eye is swelling shut. He’s lightheaded and feels like vomiting. He has lost the desire to live.

He hears the American officer yelling at him once more. The guards have started up again on his face. Joe’s world swirls and turns black. He collapses. A bucket of muddy water is thrown on him. He awakens to find two guards pulling him up and off the ground. They prop him against a shed and point to a shallow hole that two prisoners are already digging to receive him.

The prisoners have been ordered to hustle; they’re a foot deep already, and one pauses with his shovel long enough to say, “Damn it, man. Just speak to them. They’re going to bury you if you don’t.”

Joe hears the words but doesn’t move his lips. A crowd gathers: several guards, a couple of American officers, and El Lobo. The guards are laughing at Joe, shaking their heads. For reasons he never understands, the two prisoners are told to stop shoveling. Work on his grave halts, and Joe is shoved back in line as the prisoners march back to Pasay for the night. Maybe it’s dinnertime for the guards, too. Nobody likes to kill on an empty stomach.

With the help of his fellow prisoners, Joe stumbles the three miles back to the schoolhouse. All he hopes for is a chance to lie down. But the prisoners are lined up in the inner courtyard for evening roll call, and El Lobo stands with his arms folded. He calls Joe’s number. Slowly and painfully, Joe steps forward. El Lobo and two guards drag him to the commandant’s office at the front of the schoolhouse.

The commandant is finishing some paperwork behind his desk and doesn’t look up when Joe enters. His second-in-command also stands before the desk. He’s a tall, thin officer known as “Cherry Blossom” due to an insignia on the collar of his dark green uniform. Cherry Blossom has called in the U.S. Army medic who runs the dispensary. The medic looks at Joe but says nothing until the commandant looks up, stares for a moment at Joe, and says in English, “Examine this man. He can’t talk. See what’s the matter.”

The medic pulls out a tongue depressor, steps in front of Joe, and says, “Open your mouth.” Joe complies. The medic looks long and hard down Joe’s throat before stepping back and answering: “He has a badly infected and swollen throat. No wonder he can’t speak.”

The commandant returns to his paperwork. Without looking up again he says, “Okay. We need all prisoners working. Try to cure him. Dismissed.”

The medic grabs Joe by the elbow and ushers him outside and to the infirmary. Once inside he says, “You lucky sonuvabitch. I don’t know what you did to land yourself in there, but they bought my bull. You’d better sleep here tonight. I’ll try to clean you up. They messed with you good.” Joe slides to the floor while the medic grabs alcohol and bandages and hustles to swab Joe’s throat with iodine.

Cherry Blossom stands in the door. His voice is sudden, quiet yet firm. “Stand up, number 1176.”

Joe struggles to rise.

Cherry Blossom hauls the boy to his feet. Like the commandant, he speaks fluent English. “I have a son in Japan who is about your age. We have a strong bond, and I wish to return home and see him again, just like I know your parents wish to see you again someday. Your survival has caused a loss of face for the guards. If you do not go to work tomorrow, you will be killed.

“But if you go to work, it will show them a strong character. They respect courage. Go to work tomorrow, and I will find you. I will arrange for you to have an easier job for the next few days. But you must show me that I have not misjudged your character. Am I understood?”

Joe nods. Cherry Blossom turns and leaves the infirmary.

The next morning Joe can barely walk to Nichols Field. Other prisoners in his column encourage him along. Once inside the work area, a guard singles out Joe from formation, leads him over to a cooking area, and points to two huge cast-iron pots filled with water. Another prisoner is already building a fire underneath the pots.

“You’re supposed to help me today,” the prisoner says to Joe. “Frankly, I’m surprised to see you alive. Everyone is. You stoke the fire and boil the water. Look useful. You’ll live.”

Every day for the next two weeks, Joe boils water and ladles it into five-gallon tin buckets to cool for drinking. Each day during the lunch break, Cherry Blossom sidles over to the fires and passes Joe some of his food. Rice. Eggplant. Slender white-root radishes called daikon.

Joe can’t help seeing the camp’s second-in-command in a new light. Some guards are kind. After two weeks, Joe is healed enough to hoist two five-gallon buckets of water onto a pole and carry them to the guards on the worksite. He makes the rounds several times a day and soon is on a first-name basis with many of the guards. Some warm to him. One, named Tanaka, is even friendly.

“You know ‘My Blue Heaven?’”

Tanaka asks one afternoon.

“The song?”

“Hai. I like very much. Teach me the words.”

Joe chuckles. Soon Tanaka is crooning the song all over camp.

It’s a brief reprieve; Joe is still in pain, though he’s healing from the beating. Cherry Blossom notices the improvement and stops sharing his food. Joe is still feverish from malaria. His stomach aches. The open wounds on his legs and ankles aren’t getting better. His weight is dangerously low. He knows they’re going to return him to pick-and-shovel work soon. Either the work will get him, or the diseases will.

The walk to and from the field each day is becoming harder and harder. Escape is not an option—other prisoners have tried, only to be hunted down and executed. He stops trying to learn Japanese words on the blackboard. Joe knows he’s going to die at Nichols Field. It won’t be long now.

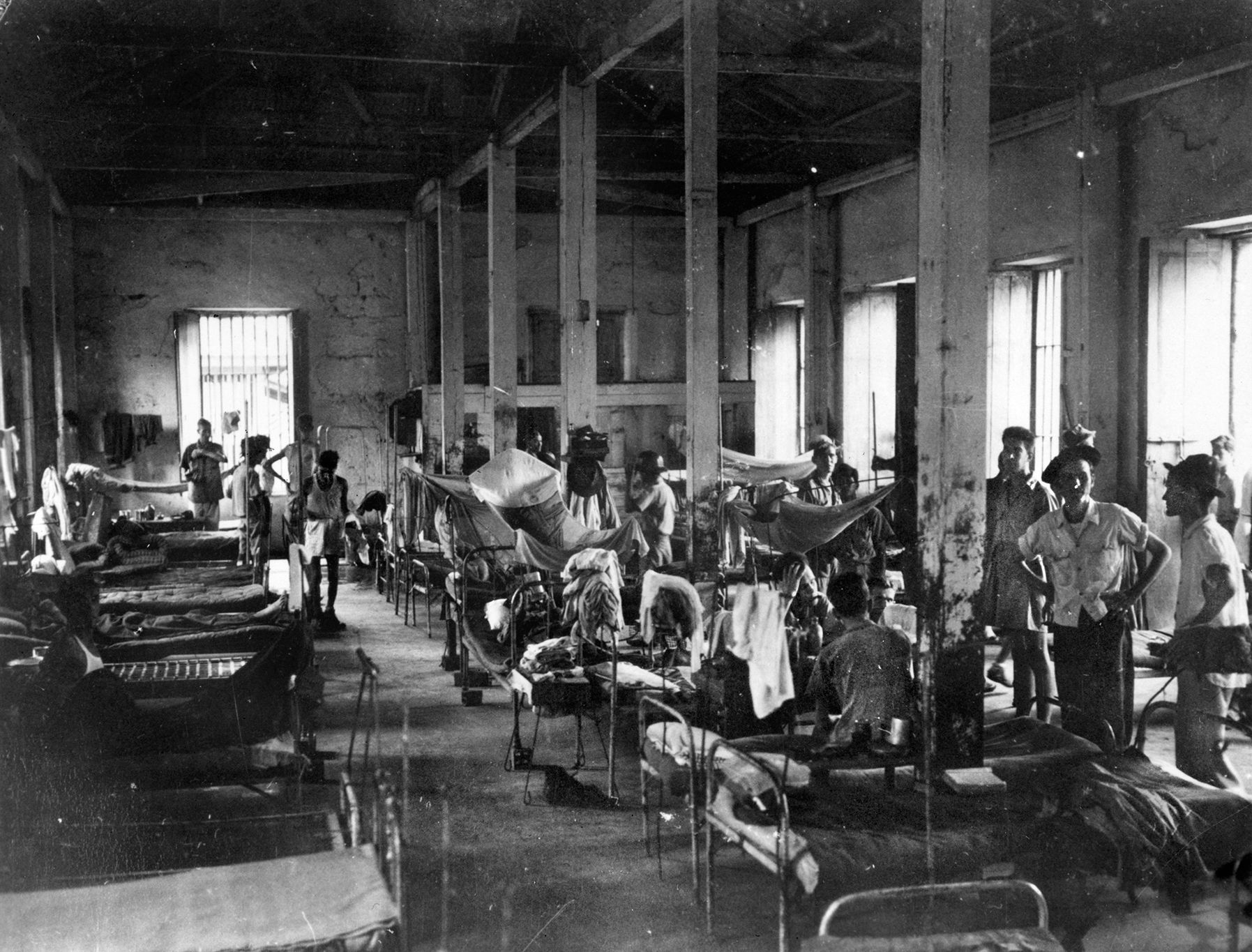

A dark plan begins to form in the boy’s mind. He remembers when a prisoner had gone insane, the Japanese had given the man a wide berth. Mental illness was to be avoided in that subculture, even feared. Manila’s Bilibid Prison houses a hospital where prisoners with mental illnesses are detained. The rations are more plentiful at Bilibid, and American doctors work there—still prisoners, but allowed to practice. If Joe can get to Bilibid, maybe he’ll live.

Joe knows he must be utterly convincing. His new plan is so desperate—so bold and beyond common sense—he needs to pull off the performance of a lifetime.

The next morning Joe heads to the worksite. Walking up to the first guard he sees, Joe removes his shirt and whips out his sharpened spoon. The boy shouts in a string of semi-fluent Japanese: “I’m going to cut your throat from ear to ear!”

The guard blinks. Joe slices into his own arm and counts in Japanese. “Ichi. Ni. San. Shi. When I get to 21, I’m gonna cut you!” The guard stares transfixed, his eyes growing larger. In a flash he emerges from his trance and runs the other direction with a shout: “Crazy!”

Blood spurts with every heartbeat. Joe has cut deeper than planned. Guards gather and stare at the commotion. Still yelling, Joe slices three long lines up his right arm. He drops his weapon and smears his face and upper body with blood. The guards shudder. They motion for two prisoners to grab Joe. He puts up a token resistance before he’s restrained.

All the rest of that day, Joe lies hogtied on the dirt of Nichols Field, bleeding, fearing he’s gone too far. At day’s end, guards prod him to his feet, tie a long rope around his neck like a dog, and march him back to the schoolhouse. The blood has congealed on Joe’s face and body, although many wounds remain open. Joe can barely stand.

Outside the entrance of Pasay lies an “eiso”—a boxlike cage made of rough-hewn lumber—about half the size of a coffin. The guards strip Joe, force him into the eiso, and padlock it shut. No prisoner, to Joe’s knowledge, has ever left the eiso alive.

Joe cannot sit or lie flat. He holds a naked fetal position throughout the sleepless night. No food or water is given to him the next morning. Prisoners whisper encouragement to him as they march toward the field. Guards yell at them to shut up. The day passes. Another night.

At daybreak, a guard pushes a rice ball through a small opening in the cage. Joe takes a bite and spits it out. It’s loaded with salt, inedible—a taunt. That afternoon, two guards poke him through the slats with bamboo sticks.

At nighttime, a sharp wind blows from the north, slicing through the cage. Joe shivers and prays for death, shaking so hard he rattles the eiso. The skies open with rain. Water seeps in around the boards. The boy twists his head and drinks. Rain falls the rest of that night. All the next day. All the next night. All the next day. Afterward, Joe loses track of time. The water keeps him breathing, but he’s finished.

Sunlight emerges at last. Voices surround him, mocking. He can’t understand the words. The door of the eiso is flung open. His eyes strain to adjust. Hands grab his ankles and drag his body across the boards. The pain is unbearable and he tries to cry out, but no words emerge. Other hands grab his wrists. His body lands on the splintery bed of a truck. His eyes stare ahead but cannot see or comprehend.

The ride is a slurry of bumps and bounces, swords of brightness and smothering blackness. He hears curses. Senses a sudden quietness. Lies still in a hushed room. A voice comes from above him. “Take it easy, son.” A needle enters his arm. He no longer feels pain.

When he awakes, Joe’s mind begins to clear. He opens his eyes, starts to understand his surroundings. Comprehends the voice.

“You’re at Bilibid Prison, son. I’m an American doctor. You’re going to make it.” Joe begins to laugh. He laughs and laughs, although the sound is only a croaking whisper. He closes his eyes and sleeps in triumph.

His audacious acting has brought down the house.

This article is adapted from Marcus Brotherton’s latest book, A Bright and Blinding Sun, a biography of Joe Johnson.

Things like this fully justify Hiroshima and Nagasaki.