By Major General Michael Reynolds

By December 24, 1944, the commander of the Sixth Panzer Army’s strongest battlegroup, SS Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Jochen Peiper, was facing the ultimate military nightmare. His Kampfgruppe was surrounded, virtually out of fuel, short of ammunition, and reduced to about a quarter of its original strength.

As a leading participant in Hitler’s last great offensive in the West, Peiper’s lightning dash through the thin American defenses in the northern Ardennes Forest had been halted in only three days by a combination of factors— bad planning, administrative weaknesses, a series of brilliant small-unit actions by the Americans, and bad luck! His small force of just over a thousand men and 25 tanks was by this time concentrated in an all-around defensive position in the tiny Belgian hilltop village of La Gleize, some 100 kilometers from his starting point behind the West Wall.

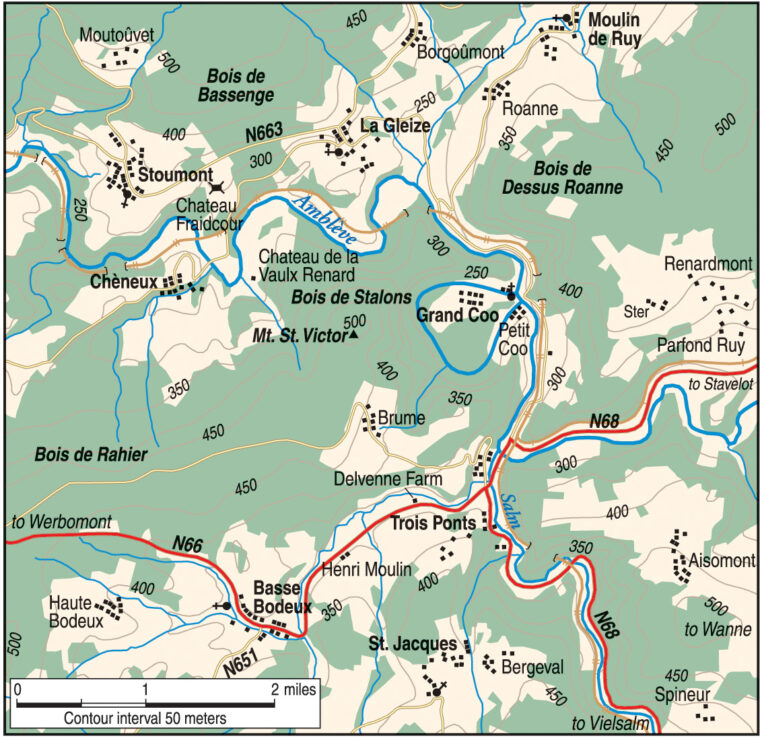

After failing to break through the 30th Infantry Division’s defenses in the Amblève Valley just to the west of Stoumont on December 19, and facing a serious fuel shortage, Peiper had gone on the defensive in the villages of Cheneux, Stoumont, and La Gleize, an area nicknamed “The Cauldron” by his men. His hopes of being resupplied and reinforced were soon dashed by the failure of the Germans to capture Stavelot. Further, a task force of the U.S. 3rd Armored Division had broken through and blocked the N-33 road north of Trois Ponts on December 20, ending forever any possibility of relief by other parts of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler.

Attacks by elements of the 82nd Airborne Division on his garrison at Cheneux and by the 30th Division and a task force from the 3rd Armored against Stoumont on the 20th and 21st forced Peiper to abandon these villages, but not before his men had inflicted grievous casualties on the Americans. Nevertheless, by the 22nd the remnants of his once mighty Kampfgruppe of nearly 5,000 men and 117 tanks, including 45 Tiger IIs, had been forced back into a perimeter of less than two square kilometers around La Gleize. These forces soon came under heavy attack from the north, east, and west. The Amblève River protected the German southern flank.

Powerful task forces from both the 3rd Armored and 30th Infantry Divisions, supported by a hundred 105mm and 155mm guns and 36 medium mortars, launched heavy assaults against Peiper’s perimeter on the 22nd and 23rd. None was successful, and the Americans resorted to heavy shelling rather than risk further casualties.

An attempt to resupply Kampfgruppe Peiper with fuel and ammunition by air during the evening of the 22nd failed when 90 percent of the canisters fell outside the tight defensive perimeter. Extraordinary measures, such as trying to float fuel drums down the Amblève River, also ended in failure.

Conditions within La Gleize were appalling. Even before the withdrawals into the final perimeter, the village was being reduced to rubble by American shelling. The majority of the civilian population had fled before being engulfed by the fighting, but some 50 Belgians remained, including the village priest, and they took cover in the substantial cellars of the mainly brick and stone houses. In one cellar alone 22 people spent six days and nights.

The Panzergrenadiers dug foxholes and took up firing positions in houses. Tanks, antitank guns, and machine guns covered all approaches, but apart from a few sentries to warn of American attacks, all remaining personnel took cover in cellars or other protected areas. Some 170 American prisoners, mainly captured in the fighting for Stoumont, were also held in cellars throughout the village and in the church. The German Aid Station was sited in a cellar of the priest’s house alongside the Kampfgruppe headquarters. The doctor and his staff had no anesthetics or drugs and were able to administer little more than first aid or carry out essential amputations. Peiper set up his personal quarters in the cellar of another house just to the north of the church.

By Saturday, December 23, hardly a building in La Gleize was habitable, but the strong cellars ensured the safety of most of their occupants. Since the Americans lifted their artillery fire immediately before each attack, the German tank crews were able to man their vehicles and the Panzergrenadiers were able to occupy their firing positions without danger. After repulsing each attack, everyone again took cover and tried to rest. Hunger haunted soldiers and civilians alike, and the cold was intense.

The condition of Peiper’s force is well described by his senior American prisoner, Major Hal McCown. He was the commanding officer of a battalion of the 30th Infantry Division and had been captured in the Stoumont fighting. In an official report made immediately after the battle, McCown, who ended up as a major general during the Vietnam era, said, “An amazing fact to me was the youth of the members of this organization—the bulk of the enlisted men were either 18 or 19, recently recruited, but from my observation thoroughly trained.”

McCown continued, “There was a good sprinkling of both privates and NCOs from the years of Russian fighting. The officers for the most part were veterans but were also very young. Colonel Peiper was 29 years old, his tank battalion commander was 30; his captains and lieutenants ran from 19 to 27 years of age. The morale was high throughout the entire period I was with them despite the extremely trying conditions. The discipline was very good…. The physical condition of all personnel was good, except for a lack of proper food…. The equipment was good and complete with the exception of some reconditioned half-tracks.

“All men wore practically new boots and had adequate clothing. Some men wore parts of American uniforms, mainly the knit cap, gloves, sweaters, overshoes and one or two overcoats. I saw no one, however, in American uniform…. The relationship between the officers and men, particularly the commanding officer, Col. Peiper, was closer and more friendly than I would have expected. On several occasions Col. Peiper visited his wounded.”

Peiper Finally Given Permission To Break Out

Although the American attacks were being beaten off, Peiper and his senior commanders knew that it was only a matter of time before they would have to surrender. They also knew that as members of the feared Waffen SS, they could expect little mercy from their enemies.

Peiper’s request for permission to break out had initially been refused by Sixth Panzer Army Headquarters, but authority was eventually delegated to Divisional level and SS Gruppenführer (Major General) Wilhelm Mohnke, Peiper’s immediate superior, finally agreed at 1400 hours on the 23rd. Stories that Peiper was ordered to bring out all his wounded, vehicles, and weapons are nonsense. It was clearly out of the question; indeed, his tanks had been virtually without fuel for over two days.

Peiper’s morale remained high after a week of fighting, a week that had seen his Kampfgruppe shattered and fail in its mission. Hal McCown gave his views, based on impressions gained during six hours of conversation with Peiper during the night of the 21st.

“He [Peiper] and I talked … our subject being mainly his defense of Nazism and why Germany was fighting,” noted the American officer. “I have met few men who impressed me in as short a space of time as did this officer.… He was completely confident of Germany’s ability to whip the Allies. He spoke of SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler’s new reserve army at quite some length, saying that it contained so many new divisions, both armored and otherwise, that our G-2s would wonder where they all came from. He … told me that more secret weapons like those (V-1 and V-2) would be unleashed.”

Although Peiper’s own morale may still have been high and his confidence in ultimate victory undiminished, this did not apply to all his men. According to his personal staff officer, Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Gerd Neuske, one member of the Kampfgruppe who was caught removing his SS collar runes, was reported as a potential deserter, put against the La Gleize church wall, and shot on Peiper’s orders.

Preparations for the final withdrawal began as soon as permission was received. Peiper held an immediate conference with his senior commanders: Werner Poetschke, commanding the remains of the 1st SS Panzer Battalion; Hein von Westernhagen, his Tiger Battalion commander; and Jupp Diefenthal, his Panzer Grenadier Battalion commander. He was apparently very calm. There was only one possible escape route, and that was to the south over the Amblève River, south again, and then east to join the rest of the division on the hills around Wanne.

It was agreed that the lightly wounded would accompany the marching column. Weapons that could not be carried were to be rendered useless, but vehicles and tanks were not to be blown up or immobilized except during artillery fire for fear of warning the Americans that a withdrawal was imminent. The badly wounded would have to be left behind, and those in less serious condition were given the task of sabotaging as many tanks and heavy weapons as possible after the main body had departed. One of Colonel Otto Skorzeny’s commando officers who had ended up by accident with Peiper’s Kampfgruppe was ordered to find a safe way over the Amblève as soon as possible. Assembly for the march out was planned for 0200 hours on Christmas Eve in the village square, just outside the church.

The commando officer and two of his men returned from their reconnaissance to say that both the railway viaduct at La Venne, 1,500 meters south of the village, and the wooden bridge beneath it were intact. Between the viaduct and a railway tunnel just to the east of it, American paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division had established a small observation post in a railway workers’ hut. Otherwise, the way south seemed to be clear. The reconnaissance group was told to eliminate the American post just before the planned river crossing at 0300 hours on Christmas Eve.

Shortly after 0200 hours on Sunday the 24th, Peiper’s column of some 800 men set off up the path known as La Couleé, passed over the Dinheid feature, and made its way down to the Amblève. It was a clear, bitterly cold night, and there was snow on the ground. The men were hungry, exhausted from lack of sleep and the stress of battle, and mentally drained by the knowledge that they had failed in their mission. They knew that they had to penetrate American lines and that any route their commander chose would lead them through extremely difficult country with a minimum of two river crossings.

The escape would inevitably be a supreme test of stamina, determination, and leadership. What the Germans did not know was that, by an extraordinary quirk of fate, the Americans in the area Peiper was planning to cross would also be moving—right across their path. Due to a serious penetration by the Germans on his southern flank, the commander of the American XVIII Airborne Corps had decided to shorten his lines and pull the 82nd Airborne back to a new and more defensible position running west from Trois Ponts. Orders for this withdrawal were given half an hour before Peiper moved out of La Gleize.

By means of four separate eyewitness accounts from men who took part in this march, it is possible to build a reasonably clear picture of the final hours of Kampfgruppe Peiper. The accounts are those of Major McCown, whom Peiper took with him as a type of hostage; Karl Wortmann, a member of Peiper’s 10th SS Anti-Aircraft Company; Yvan Hakin, one of two Belgians who were forced to act as guides in the early part of the withdrawal; and a member of the Luftwaffe flak unit attached to the Kampfgruppe, Feldwebel (Sergeant) Karl Laun.

(This author was able to interview Hakin shortly before his death and was present when Karl Wortmann returned to the Ardennes with other veterans in 1985 and 1991 to discuss the events of December 1944.)

Peiper knew that other elements of his division were holding the Coo area east of the Amblève on the morning of the 23rd. Whether he knew that they had been forced to pull back to the south that afternoon is unclear, but in any case they were the nearest German forces to him, and that is presumably why he made the bridge over the Amblève at the Coo cascade his first objective. He planned to reach it by crossing two footbridges over the “dead arm” of the river, just to the west of the cascade.

“A Sea Of Fiercely Burning Vehicles”

The railway viaduct and tunnel between La Gleize and Coo would have been a much shorter and easier route, but Peiper, having passed under it on the 18th, knew that the viaduct had been blown. A major span had, in fact, been destroyed by the Germans during their earlier retreat on September 9. What he did not know was that the Coo cascade bridge had also been blown by the Americans.

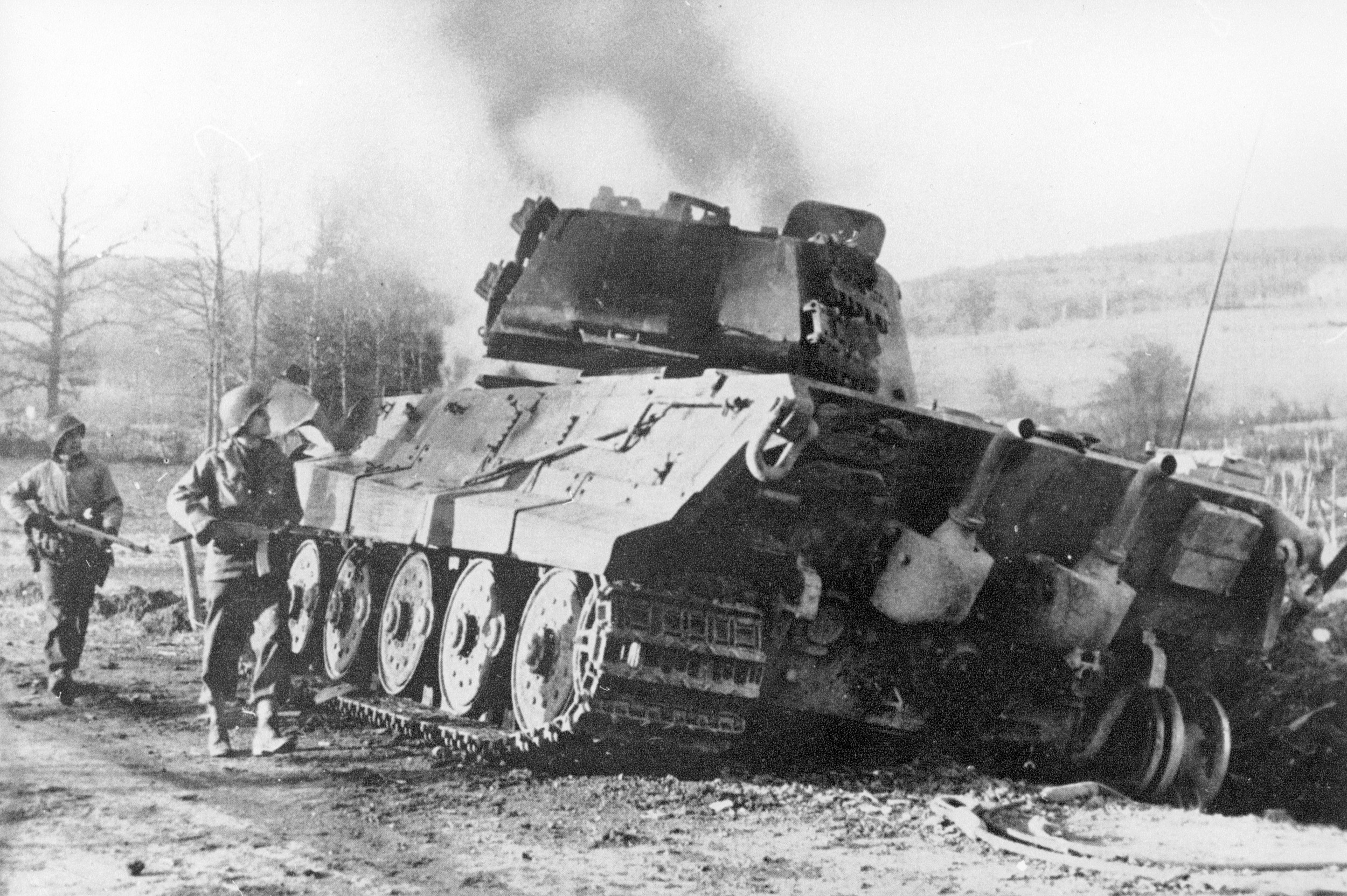

On reaching La Venne, the Germans chose Hakin and another Belgian from a group of civilians sheltering there to act as guides through the thick forest known as the Bois de Stalons. McCown makes no mention of these guides but says, “Col. Peiper and I moved immediately behind the point, the remainder of his depleted Regiment following in a single file…. We crossed the Amblève River near La Gleize on a small highway bridge immediately underneath the railroad bridge and moved generally south, climbing higher and higher [through knee-deep snow] on the ridge line. At 0500 we heard the first tank blow up and inside thirty minutes the entire area formerly occupied by Col. Peiper’s command was a sea of fiercely burning vehicles, the work of the small detachment he had left behind to complete the destruction of all his equipment.”

Karl Wortmann put the time of this destruction an hour later, which accords with other American reports; he recalled thinking it was his sixth Christmas at war!

Soon after first light, the Americans advanced on La Gleize from three sides, and to their great surprise and relief met only light resistance. The few skirmishes that did take place were with the stay-behind parties and a few Germans who had not received the order to withdraw. Between 100 and 300 prisoners were taken, most of them badly wounded, and 170 American GIs were released. Thirteen Belgians were killed as a result of the fighting in and around their village.

Meanwhile Peiper had reached the heights of Mont St. Victor (520 meters) where he could see that the bridge over the Coo cascade was blown. There was more bad news to come. A reconnaissance party reported the dominating village of Brume occupied by Americans (A Company of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment). With his direct way to safety blocked and U.S. spotter aircraft already searching for his column, Peiper had no option but to lie up until dark. He chose the deep gully known as the Trou des Mouchettes, just east of Beauloup. It has been suggested that the Germans ended up in this area after ignoring the advice of their Belgian guides and getting lost. While it is true that Peiper vetoed attempts to lead the column along the widest and most obvious forest trails and insisted on using more discreet routes, the decision to remain in this covered ravine during daylight was quite deliberate.

According to McCown, while his men rested, “Col. Peiper, his staff and myself with my two guards spent all day of the 24th reconnoitering a route to rejoin other German forces.” The route chosen passed the Calvary de la Croisette on the approach to Brume, bypassed that village to the west, and then ran down the steep slopes of the Bois de Toirbaileu toward the tiny hamlet of Henri Moulin on the main N-23 Trois Ponts to Basse Bodeux road.

McCown remembered, “At 1700, just before dark, the column started moving again…. We pushed down into the valley in single column with a heavily armed point out ahead. The noise made by the entire 800-man group was so little that I believe we could have passed within 200 yards of an outpost without detection. As the point neared the base of the hill I could hear quite clearly an American voice call out ‘Halt! Who is there?’ The challenge was repeated three times, then the American sentry fired three shots.

“A moment later the order came along the column to turn around and move back up the hill. The entire column was halfway back up the hillside in a very few minutes. A German passed by me limping. He was undoubtedly leading the point as he had just received a bullet through the leg. The Colonel spoke to him briefly but would not permit the medics to put on a dressing; he fell in the column and continued moving on without first aid.”

The Belgian version of this incident confirms that one man was wounded and says the point did not return fire in order to maintain the secrecy of the withdrawal. In the confusion caused by the incident the two Belgian guides managed to escape and return to La Venne.

“The point moved along the side of the hill for a distance of half a mile, then turned again down into the valley, and this time passed undetected through the valley and the paved road which ran along the base,” added McCown. “The entire 800 men were closed into the trees on the other side of the valley in an amazingly short period of time. Several American vehicles ‘chopped’ the column.”

The commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, Major General Jim Gavin, later confirmed the presence of one of the U.S. vehicles: “Earlier in the night a jeep driver had reported that as he was driving in the vicinity of Basse Bodeux he encountered troops wearing full field equipment walking in the woods towards the east. They hit the ground and took cover and acted very evasive as his jeep neared them.”

The German column moved over the N-23 in small groups in the region of the Delvenne farm. Karl Laun describes “packs of 20 men each” and Wortmann mentions a sharp 20-minute clash during the crossing, which resulted in at least two Germans being wounded.

The SS men continued south, climbing the hill past Mont de Fosse and reaching the high ground around Bergeval.

Col. Peiper Makes A Mysterious Disappearance

“I could tell then that Col. Peiper was basing his direction of movement on the explosion of American artillery fire as the probable location of his friendly forces,” McCown mentioned. “His information as to the present front lines of both sides was as meager as my own as he had no radio and no other outside contact…. We continued moving from that time on continuously up and down rugged hills, crossing small streams, pushing through thick undergrowth and staying off and away from roads and villages.

At around 2200 Col. Peiper, his executive officer and his S-3 [Neuske and Hans Gruhle] disappeared from the forward command group. I and my two guards were placed in charge of the Regimental surgeon whose familiar Red Cross bundle on his back made it easy for me to walk behind. I tried in vain to find out where Col. Peiper went; one friendly enlisted man of his Headquarters told me that Col. Peiper was very tired, and I believe that he and a few selected members of his staff must have holed up in some isolated house for food and rest, to be sent for from the main body after they had located friendly forces.

“The change of command of the unit also wrought a change in method of handling the men. A young captain in charge of the leading company operated very close to me…. I heard him tell my guards to shoot me if I showed the slightest intention of escaping, particularly when we neared Americans. Whereas Col. Peiper had given a rest break every hour or so, there were no breaks given under the new command from that time until I escaped. The country we were now passing through was the most rugged we had yet encountered.

“All the officers were continuously exhorting their men to greater effort and to laugh at weakness. I was not carrying anything except my canteen, which was empty, but I know from my own physical reaction how tired the men with heavy weapon loads must have been. I heard repeated again and again the warning that if any man fell behind the tail of the column he would be shot. I saw some men crawling on hands and knees. I saw others who were wounded but who were being supported by comrades up the steep slopes.”

Laun described how the men suffered during the wearying march: “A burning thirst, which is caused by the dry cold, bothers us most. The men tear the ice-covered snow from the trees and suck it. Others, animal-like, throw themselves over each puddle and drink the muck…. The men are becoming more and more exhausted. Here one falls by the wayside, there another breaks formation…. When we take a five minute break some fall asleep on their feet, don’t wake up when we resume the march—and in the darkness we don’t see them again…. We stumble over rocks, get stuck in bogs, tear ourselves on the primeval undergrowth.”

“We approached very close to where artillery fire was landing, and the point pushed into American lines three times and turned back,” McCown remembered. “I believe the Germans had several killed in these attempts. [It seems reasonably certain that these attempts occurred near a place known as St. Jacques, 500 meters southwest of Bergeval on the road to Fosse.] Finally, the commander decided to swing over the ridge and come down in the next valley…. I was firmly convinced by this time that they did not know where they were on the map as there were continuous arguments among the junior officers….

“I heard the captain say that he would attempt to locate a small village where the unit could hole up for the rest of the night. At approximately 0100 I believe I heard word come back that a small town [almost certainly the hamlet of Bergeval] was to the front which would suffice…. My guards held me back near the position which was occupied by the covering force between the village and the west….

“The outpost had hardly moved into position before firing broke out not very far from where I was standing. My guards and I hit the ground, tracer bullets flashed all around us and we could hear the machine-gun bullets cutting the trees very close over us. The American unit, which I later found out was a company, drove forward again to clear what it obviously thought was a stray patrol…. The mortar fire fell all around the German position… . Shrapnel cut the trees…. I could hear commands being shouted in German and English…. There was considerable movement around me in the darkness. I lay still for some time waiting for my guards to give me a command.

“After some time I arose cautiously and began to move at right angles from the direction of the American attack, watching carefully to see if anyone was covering or following me. After moving approximately 100 yards I turned and moved directly toward the direction from which the American attack had come. I can remember that I whistled some American tune but I have forgotten which one it was. [He later recalled it was “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”] I had not gone over 200 yards before I was challenged by an American outpost of the 82nd Airborne Division.”

The American unit involved in this fighting was Captain Archibald McPheeter’s I Company of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. The unit history gives more details: “Most units were able to do so [withdraw], but some of the 3rd Battalion, and I Company in particular, had to fight its way through. The main body of the company was able to get through without serious casualties, but one platoon left at the river [Salm] as rear guard was especially hard hit and lost over half its men before it could extricate itself.”

The final obstacle for Peiper’s exhausted men was the Salm River. A Belgian farmer in Bergeval was forced to act as a guide for a major part of the column, and he showed the way to Rochelinval via a lane running over the Fosseuheid crest. The river there was a raging torrent.

“Most of the comrades sat along the high railway embankment,” wrote Wortmann. “Three meters below us we saw the rushing water of the Salm. The foam sprayed a cold shower down our backs. We then had to make our way over stones that some hearty comrades had lain in the ice-cold water. A human chain was assembled, and each man was pulled by the next, stone by stone, sometimes waist-deep in water, to the far bank…. Several times the chain was broken when comrades stumbled from the stones. Day was already dawning as the last man reached the other bank.”

Karl Laun was less than enthusiastic about his reception on the far bank and gives an interesting view of his Waffen SS comrades: “I am icy-wet when I reach the opposite bank. The reception committee already awaits us—one of our SS friends. One can’t recognize his rank in the darkness, but he shows his superiority by dealing out curses and kicks to the stragglers. On the other side of the river these courageous gentlemen were quiet and subdued; but now, knowing the last Americans are safely behind them, they at once assume again the typical SS arrogance.”

On Christmas Day, 770 survivors of Kampfgruppe Peiper reached the sanctuary of the east bank. They had covered roughly 20 kilometers in almost exactly 36 hours and only 30 men had been lost on the way. As far as this author can establish, every officer under Peiper’s command who had crossed to the north bank of the Amblève survived to reach Wanne. In any other army these men would have been treated as heroes, fêted and sent to the rear, or even home, to rest and recuperate. However, that was not the way of the Waffen SS, particularly with Hitler’s Reich facing defeat and invasion from the East and West.

Within three days the survivors of Kampfgruppe Peiper were fighting with the rest of their division near Bastogne, and within two months they would be leading their Führer’s last offensive of the war—against the Red Army in Hungary.

Peiper Sent Back Into Final Battle

Jochen Peiper reported to his divisional commander, Wilhelm Mohnke, at the Château Wanne on Christmas morning and was ordered to establish his headquarters at Petit Thier, seven kilometers to the southeast, in anticipation of a further task. The fact that Peiper was physically and mentally exhausted seems to have been of no consequence. However, he took no part in the 1st SS Panzer Division’s actions in the Bastogne area. It is this author’s belief that he was in fact evacuated to Germany almost immediately for convalescence.

Peiper’s name appears on no staff list of divisional appointments, and all senior appointments are shown being filled by other officers. Accusations made later that he ordered a stray and exhausted American soldier to be shot at Petit Thier on January 10, in the presence of two brother officers, one of whom was von Westernhagen, the commander of the Corps’ Tiger Battalion, can be dismissed. By then the division had been fighting near Bastogne for two weeks. There is no way its two senior tank commanders would have been left behind in an area held by a Volksgrenadier division!

The first mention of Peiper after the escape from “The Cauldron” was on February 6, 1945, when a press release mentions him receiving the swords to his Knight’s Cross from Hitler two days previously. His next appearance with the 1st SS Panzer Division was in Hungary on February 14, 1945, in command of the Leibstandarte’s ‘Panzer-Gruppe’.

Click here to read all about Joachim Peiper’s grisly death after his military career…

Two things stand out about this account that attempts a lame exoneration of the events at Malmedy. First is command responsibility. Several of the enemy were hanged after the war from both the Western front and Southeast Asia for just that reason. Second, several of those at Malmedy survived being shot and described the events as being Peiper’s actions. Also, in the German Army, no underling would have made a decision of that nature. Side note: The later assassination of Peiper in France received the level of investigation it warranted in view of the number of potential “suspects”.

This is an apologist spin on an the actions of a homicidal war criminal. Please exert better editorial control on your content.

I believe the author, Major General Michael Reynolds would take issue with the characterization that this story is an “apologist spin.”

Much of the story is quoted from the recollections of American Major (later General) Hal McCown, who accompanied Peiper as a POW during the German escape. General McCown’s recollections seem honest, and straight forward, but also without emotion, which might be why some of the narrative seems somewhat sympathetic to the plight of the Germans. Other quotes come from German participants, likely more sympathetic in recalling their experiences.

General Reynolds wrote a number of stories for us before he passed away in 2015. I spoke to him several times, and on one occasion we discussed Peiper briefly. Reynolds was adamant that whether Peiper was present, or not, during the killing of POWs and civilians, as the commander of his men, he bore total responsibility for their actions. That Peiper was a zealous Nazi is clearly stated in the story.

General Reynolds was a combat veteran of the Korean War. He also served as Nato’s Allied Command Europe Mobile Force (Land) in Germany, and later as Director of Nato’s Military Plans and Policy Division. You can find his obituary, with more information on his military service here: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/12035846/Major-General-Mike-Reynolds-obituary.html