By Al Hemingway

Hero or scapegoat? Even with the passage of nearly 144 years since the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg was fought in the rolling hills of southern Pennsylvania, controversy still shadows the role—or lack of role—played by one of General Robert E. Lee’s most trusted lieutenants, Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart. Did Stuart venture irresponsibly on a “joy ride,” as some have suggested, depriving Lee of his “eyes and ears” on the eve of the war’s most pivotal battle, or did Stuart merely follow Lee’s orders to the letter and in an attempt to provide him with invaluable intelligence on the movements of the Army of the Potomac?

In their new offering, Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg (Savas Beatie, New York, 2006, 428 pp., illustrations, maps, photos, index, $32.95, hardcover), authors Eric J. Wittenberg and J. David Petruzzi have done a wealth of research in an attempt to answer those and other pertinent questions surrounding the mysterious disappearance of Stuart’s horsemen during the crucial period just prior to the battle.

In their new offering, Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg (Savas Beatie, New York, 2006, 428 pp., illustrations, maps, photos, index, $32.95, hardcover), authors Eric J. Wittenberg and J. David Petruzzi have done a wealth of research in an attempt to answer those and other pertinent questions surrounding the mysterious disappearance of Stuart’s horsemen during the crucial period just prior to the battle.

The writers traced every foot of Stuart’s ride, from the moment he departed Salem, Va., on June 24, 1863, until he finally reached Lee’s command on the second day of the battle on July 2. They gleaned information from every possible source in an attempt to provide unbiased answers to the myriad questions that fostered heated arguments among veterans of the battle and carried over to Civil War historians down through the years to the present.

Much has been written about Stuart’s interpretation of Lee’s orders and his supposed failure to provide the Confederate Army with the proper screening and intelligence. The authors, however, discovered an overlooked dispatch from Stuart to Lee warning him of the movement of the Army of the Potomac four days prior to the clash at Gettysburg. Obviously, the all-important letter never reached Lee’s hands. Lee further wrote in his official report that “Stuart acted within the scope of his orders in making his ride.”

In spite of all the finger-pointing directed against Stuart, Lee had ample cavalry at Gettysburg to gather information on the Union Army’s whereabouts. Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins’s brigade was with Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s corps on the battlefield, and Brig. Gens. William E. “Grumble” Jones and John D. Imboden were ordered by Lee to remain in Maryland and provide a line of retreat for his army. Consequently, they played virtually no role in the battle, although they could have been summoned if Lee thought it was necessary.

As for a “joy ride,” it was anything but that for the gray horsemen. The ride to Gettysburg was a grueling test of man and animal. Most Confederate mounts were in dire need of feed and shoes when Stuart’s men fortuitously captured 150 wagons of oats and supplies. Some of Stuart’s detractors have made an issue of this, charging that the cumbersome vehicles slowed down his rate of march. That is undeniably true but, as one of Stuart’s officers later commented, the captured food was a “godsend” for the horses.

The Union cavalry also deserves at least a portion of the credit for the Confederacy’s defeat at Gettysburg. Stuart’s men fought some nasty scrapes against the Federals in towns such as Westminster, Hanover, and Hunterstown, where the blue riders fought brilliant delaying actions to further impede his progress. The 1st Delaware Cavalry’s brave stand at Westminster and the suicidal charge of the 11th New York Cavalry at Fairfax Court House are but two such instances that the authors cite in their book.

Stuart deserves a portion of the blame as well. Instead of opting for the Hopewell Gap route, as suggested by his scout John Mosby, Stuart elected to take Glasscock’s Gap instead. By doing so, he ran headlong into Maj.

Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps. He then waited for Mosby for 10 long hours at Buckland Mills before continuing his ride, a decision that further disrupted his fragile schedule.

“If Stuart disappointed anyone at Gettysburg, he more than redeemed himself during the retreat to Virginia,” Wittenberg and Petruzzi write. “His performance during those difficult days, as well as that of his vaunted cavaliers, to whom the previous few weeks must have seemed a lifetime, was nothing short of magnificent. As we hope this study has demonstrated, no single person or condition can or should be made to shoulder the blame for the crippling Southern loss at Gettysburg. Rather, a combination of circumstances led to the Confederate disaster.”

To the Limit: An Air Cav Huey Pilot in Vietnam, by Tom A. Johnson, Potomac Books, Va., 2006, 409 pp, photos, maps, index, $26.95, hardcover.

To the Limit: An Air Cav Huey Pilot in Vietnam, by Tom A. Johnson, Potomac Books, Va., 2006, 409 pp, photos, maps, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Helicopter pilots, sometimes called “rotor heads,” were a special breed during the Vietnam War. They often ignored regulations by sporting handlebar mustaches, unconventional dress, and an open disdain for authority. But ask any Vietnam veteran who ever needed a medevac or resupply, and they will tell you that there were no braver individuals in the war.

One such person was CW2 (Chief Warrant Officer) Tom Johnson, who served with the prestigious 229th AHB (Assault Helicopter Battalion) from 1967-68. His unit received numerous accolades for performing outstanding service, from the Ia Drang Valley to Hue City to Khe Sanh. Johnson’s account of his service is both funny and poignant. He pays due homage to those who gave the ultimate sacrifice during the conflict. The death rate among helicopter crews was extremely high: one out of 18 was killed. Nearly 2,200 pilots and 2,300 crew members died in Vietnam.

Surviving the war, Johnson returned home and became a successful businessman. His awards are numerous and impressive: the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with five Silver Leaf clusters, and a Bronze Star. He logged an astronomical 1,600 hours flying time in his year tour of duty. Today, one of the choppers he piloted is located at the Smithsonian Institute’s Air and Space Museum. Another is situated at the Pacific Coast Air Museum.

To the Limit is an absorbing book. Whether or not you served in the military or ever flew in a helicopter, it will grab you and hold your attention.

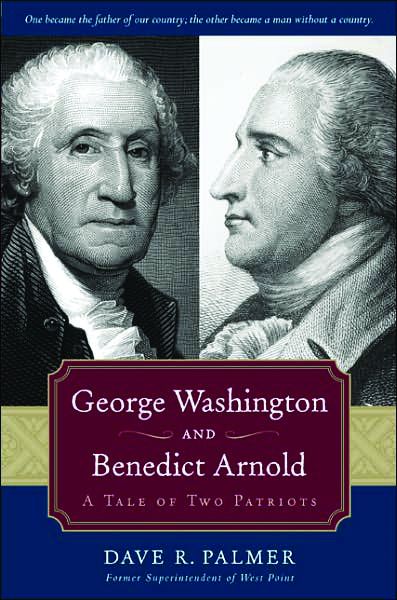

George Washington and Benedict Arnold: A Tale of Two Patriots, by Dave R. Palmer, Regnery Publishing, Inc., Washington, DC, 2006, 412 pp., maps, illustrations, $29.95, hardcover.

George Washington and Benedict Arnold: A Tale of Two Patriots, by Dave R. Palmer, Regnery Publishing, Inc., Washington, DC, 2006, 412 pp., maps, illustrations, $29.95, hardcover.

“One became the father of our country, the other became a man without a country,” writes military historian Lt. Gen. Dave R. Palmer, USA (Ret.) of George Washington and Benedict Arnold, two individuals who started out on identical paths and ended up in radically different camps during the American war for independence.

In the beginning, both men felt the same patriotic fervor toward their new country. Both were passionate about the personal freedom and liberties the fledgling United States had to offer. In the early days of the Revolutionary War, Washington suffered a series of setbacks, while Arnold’s star shone. Realizing that he had a competent officer in Arnold, Washington favored the younger man by promoting him to brigadier general. Jealousies within Washington’s officer ranks stymied Arnold’s career, and he was overlooked for promotion to major general (Arnold finally received the higher rank, but was junior to other officers, he felt, were incompetent).

Arnold’s patriotism faded, and the Connecticut merchant planned to desert the Continental Army and offer his services to the British. Before his departure, he met with British Major John Andre to plan the surrender of West Point, a key military installation on the Hudson River in New York. Arnold’s scheme was uncovered and he barely managed to escape, while Andre was captured and later hanged as a spy. As a result of his treachery, Arnold’s name has been synonymous with “traitor” ever since.

Although undeniably brave and competent in battle, Arnold lacked the one essential ingredient that makes a person stand out—character. Washington, on the other hand, was the very embodiment of such qualities. As David Abshire, former president of the Center for the Study of the Presidency, has remarked: “The heart of Washington’s leadership was pure character.”

Mud: A Military History, by C.E. Wood, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2006, 190 pp., illustrations, $23.95, hardcover.

Mud: A Military History, by C.E. Wood, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2006, 190 pp., illustrations, $23.95, hardcover.

Ask a soldier from any war about the terrible weather conditions he endured, and he would probably place mud at or near the top of the list. Not only did the infantryman have to slog through the mire, but trucks, jeeps, tanks, artillery pieces, and other equipment bogged down in the slurry mixture as well.

Not even the greatest strategists could foresee the effects from mud. As the author explains, if Napoleon had not waited for the mud to dry, the Battle of Waterloo might have had a very different outcome. The gooey slime also stopped the seemingly indestructible German Army during the Russian campaign of World War II, and the Nazis were forced to wait for colder weather to freeze the mud and allow them to continue their advance. By then it was too late—“General Winter” had become their greatest enemy, and the Russians’ greatest ally.

During the Vietnam conflict, the United States attempted to seed the clouds so that torrential monsoon rains would continue for a longer period and curtail the movement by North Vietnamese Communists of supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. As the reader learns, a simple thing such as mud “can be a very significant factor of success or failure on the battlefield.”

Crystal Clear: The Struggle for Reliable Communications Technology in World War II, by Richard J. Thompson, Jr., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., NJ, 2007, 230 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $54.95, hardcover.

Crystal Clear: The Struggle for Reliable Communications Technology in World War II, by Richard J. Thompson, Jr., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., NJ, 2007, 230 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $54.95, hardcover.

Whether you are commanding a regiment, battalion, or division in battle, the ability to communicate with your subordinates is paramount. Movement of troops, artillery, and other supporting arms is essential to defeating the enemy. Prior to today’s modern technology, commanders had to rely on runners or couriers mounted on horseback to deliver their messages in a timely manner.

World War II ushered in a whole new world of communications with the widespread use of the radio. From its infancy, quartz crystal was only used by amateur radio aficionados. With the start of the war, however, the American military quickly grasped its importance. The mineral, they realized, could vastly improve their ability to communicate.

Second only to the Manhattan Project in its scope, the U.S. government set out to mine quartz and transport it to laboratories to create a quartz crystal unit. Engineers designed a crystal oscillator, but then had to go back to the drawing board to repair a major flaw called “aging.” In the end, however, the effort proved to be a huge success.

Because of their efforts, quartz is commonly used today in such electronic devices as watches, color televisions, cell phones, and computers. This is an engrossing story of one of the lesser-known projects of World War II and how it improved our way of life tremendously.

Soldier Slaves: Abandoned by the White House, Courts, and Congress, by James W. Parkinson and Lee Benson, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 249 pp., illustrations, index, $28.95, hardcover.

Soldier Slaves: Abandoned by the White House, Courts, and Congress, by James W. Parkinson and Lee Benson, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 249 pp., illustrations, index, $28.95, hardcover.

The ordeal of those who endured and survived the horrific Bataan Death March in April 1942 has become legendary. But what happened to the surviving POWs after their infamous trek? Most faced three and a half years of forced labor. In essence, they were slaves of the Japanese government, required to work long, grueling hours at one of the 169 camps dotted throughout the country. If they stepped out of line, they would suffer beatings or inhumane torture by sadistic prison guards.

Upon their return, the men were told to remain silent concerning their terrible treatment, and for years nothing was mentioned about their horrendous suffering. Finally, their plight became public knowledge and their case went before Congress to receive compensation from the Japanese government. With the assistance of Senators Joseph Biden and Orrin Hatch, a team of lawyers tried unsuccessfully to have long overdue reparations given to the survivors.

James Parkinson, a lawyer who was on the case, and journalist Lee Benson have written a compelling story of the human tragedy. As suggested by the book’s title, the brave men who were abandoned at the outset of World War II were abandoned once again six decades later. The Japanese government has still not made adequate restitution or reparation to the victims of their sadism—American or otherwise.

D-Day Survivor: An Autobiography, by Harold Baumgarten, Pelican Publishing, 2006, 176 pp., illustrations, index, $25.00, hardcover.

D-Day Survivor: An Autobiography, by Harold Baumgarten, Pelican Publishing, 2006, 176 pp., illustrations, index, $25.00, hardcover.

There has been a plethora of books on D-Day depicting the exploits of the famed 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions’ battles behind enemy lines attempting to secure vital objectives for the advancing troops. And all of these accounts deserve to be told. The heroic exploits of these men must never be forgotten.

However, one unit that landed at Omaha Beach on that fateful day in June 1944 has received scant attention. These were the soldiers of the 29th Infantry Division. The 29th, dubbed the “Blue and Gray Division,” has a long, proud lineage in the U.S. Army, dating all the way back to the French and Indian War.

Harold Baumgarten landed with the 116th Infantry, 29th Division, on D-Day and was wounded five times before being medically evacuated. Before 8 am that day, his unit sustained an incredible 85 percent casualty rate. He wrote this vivid description of the terrible events on Dog Green Beach to let people know of the sacrifices endured by him and, more importantly, his comrades.

After the war, Baumgarten received a bachelor of arts degree from New York University and a master’s and medical doctorate from the University of Miami. Today he lectures on D-Day, especially on the role of the fabled 29th Division, throughout the country. Baumgarten has received numerous awards and accolades over the years, but the highest honor that is bestowed upon him and his comrades is simply being a “Twenty-niner,” a soldier in one of finest units in the United States Army.

Grace Under Fire: Letters of Faith in Time of War, edited by Andrew W. Carroll, Doubleday, New York, 2007, 160 pp., illustrations, $16.95, softcover.

Grace Under Fire: Letters of Faith in Time of War, edited by Andrew W. Carroll, Doubleday, New York, 2007, 160 pp., illustrations, $16.95, softcover.

At no time in a person’s life does the specter of death weigh so heavy as during time of war. The old adage that there are “no atheists in a foxhole” illustrates the fear that accompanies those individuals on the front lines. Andrew Carroll of the Legacy Project has gathered a series of letters, from the American Revolution to the present-day men and women fighting in the war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan. Before each piece of correspondence is a brief synopsis explaining the events in that particular period of our nation’s history.

Grace under Fire offers the reader a glimpse at the life of a serviceman in a combat situation through his or her own words. Some letters are lighthearted, while others express the sadness at losing a friend in battle. It is an inspirational work that details the religious beliefs not only of those men and women in uniform, but also of the gallant clergymen who also risk their lives to bring solace to the soldiers under fire.

Army: An Illustrated History, by Chester G. Hearn, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2006, 192 pp., illustrations, $29.95, hardcover.

Army: An Illustrated History, by Chester G. Hearn, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2006, 192 pp., illustrations, $29.95, hardcover.

From its humble start as a motley group of militia in the American Revolution to the present day high-tech force of the 21st century, the United States Army has served our country honorably for over two centuries. Military historian Charles Hearn not only provides the reader with a comprehensive look at the Army’s past exploits, but also delves into the Army of the future. The book has numerous black and white and color photographs of the weapons, garments, and equipment that will be used by our soldiers in the ensuing years.

One interesting area the author mentions is the rapid advance of electronics in tomorrow’s Army. Hearn writes, “Weapons engineers have told General Peter Schoomaker, army chief of staff, that by 2010 computers will be replaced by electronics so tiny they can be embedded in clothing or eyeglasses and broadcast on the human retina.” With all the new technology being incorporated for use, the U.S. Army will indeed be a force to be reckoned with around the globe.

Wilson’s Creek, Pea Ridge & Prairie Grove: A Battlefield Guide with a Section on Wire Road, by Earl J. Hess, Richard W. Hatcher III, William Garrett Piston, and William L. Shea, University of Nebraska Press, 2006, 282 pp., maps, illustrations, $19.95, softcover.

Wilson’s Creek, Pea Ridge & Prairie Grove: A Battlefield Guide with a Section on Wire Road, by Earl J. Hess, Richard W. Hatcher III, William Garrett Piston, and William L. Shea, University of Nebraska Press, 2006, 282 pp., maps, illustrations, $19.95, softcover.

For anyone planning a trip to the Wilson’s Creek, Pea Ridge, or Prairie Grove battlefields, this book would be an excellent choice to take along as a handy reference guide. Considered by historians as the “three most important battles fought west of the Mississippi River,” the battles are still little known by the public at large. The authors have sought to address that anomaly by assembling detailed directions to the historic sites as well as brief summaries of the action, people involved, and letters from the common foot soldiers involved in the fighting there.

Each map has a stopping point where the Civil War enthusiast can gain a better knowledge of the campaigns and the reasons why the commanders utilized the strategies they did at the time. In the back of the book, the authors list all the units involved in the battles as well. This indispensable guide is the first of its kind for these three crucial battles fought in territory that each side considered vital to its successful prosecution of the war.

Concise History of the World: An Illustrated Time Line, edited by Neil Kagan, National Geographic, Washington, D.C., 2006, 416 pp., maps, illustrations, $44.00, hardcover.

Concise History of the World: An Illustrated Time Line, edited by Neil Kagan, National Geographic, Washington, D.C., 2006, 416 pp., maps, illustrations, $44.00, hardcover.

One of the premier publishers of one of the longest running magazines in the United States has produced a coffee table book that will delight any history buff. The editors begin at the dawn of time and follow each century, touching upon individuals, battles, religions, diseases, inventions, and other epochal events of the age. Each chapter begins with a brief essay that puts that era into historical perspective. The timeline then examines different parts of the world and explains what was occurring in the world at the time.

Middle school and high school students will find the book a tremendous asset in their social studies classes. It is easy reading and filled with breathtaking black-and-white and color photographs that bring the accompanying text to life. National Geographic has provided the reading public with another excellent reference source for people of all ages.

The Hungarian Revolution 1956, by Erwin A. Schmidt & Laszlo Ritter, Osprey Publishing, 2006, 64 pp., illustrations, index, $17.95, softcover.

The Hungarian Revolution 1956, by Erwin A. Schmidt & Laszlo Ritter, Osprey Publishing, 2006, 64 pp., illustrations, index, $17.95, softcover.

Osprey Publishing of Great Britain has long been one of the leaders in printing brief accounts of historical episodes, military equipment, battles, and fortifications. Their newest offering dealing with the Hungarian uprising in 1956 is no exception. The authors explain how the political climate of the period shaped the Hungarian nation after World War II. But it was a peaceful student demonstration 11 years after the war, in October 1956, that sparked a gallant if short-lived revolution in Hungary. Word soon spread that unarmed civilians had been fired upon. This report enraged and spurred the population to take up arms against their Russian occupiers.

Although the Hungarians fought bravely, the revolt was crushed by the mighty Soviet military machine that November. The writers have delivered an excellent overview of that tragic moment in European history, and its ultimate bearing on the fall of European Communism in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Finding the Target: The Transformation of American Military Policy, by Frederick W. Kagan, Encounter Books, 2006, 444 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Finding the Target: The Transformation of American Military Policy, by Frederick W. Kagan, Encounter Books, 2006, 444 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Military analyst Frederick W. Kagan has written a thought-provoking book on the future strategic policies of the American military. Tracing the metamorphosis of the military from Vietnam, when it underwent a gigantic rebuilding process, to the present-day crisis in the Middle East and North Korea, he discusses the shortcomings of the strategy supported by the Pentagon and other defense agencies.

Kagan maintains that the heavy dependence on the technological aspect of the armed services is secondary to the most important aim of any war, which is the “use of force to achieve political objectives.” The basic tenets of war, written by Carl von Clausewitz in his influential study, On War, written over 175 years ago, still remain true today, Kagan observes. To be successful on the battlefield and achieve victory, Clausewitz maintained, one must successfully control the “trinity of war”—the people, the government, and the army. “A theory that ignores any one of them,” he wrote, “or seeks to fix an arbitrary relationship between them would conflict with reality to such an extent that for this reason alone it would be totally useless.” One wonders whether the architects of the current war in Iraq bothered to read Clausewitz’s book.

Troubled Hero: A Medal of Honor, Vietnam, and the War at Home, by Randy K. Mills, Indiana University Press, 2006, 167 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Troubled Hero: A Medal of Honor, Vietnam, and the War at Home, by Randy K. Mills, Indiana University Press, 2006, 167 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Ken Kays was a baby-faced 20-year-old college dropout when he went to Vietnam as a conscientious objector. Even though he was refused the official status by the U.S. Army, he was assigned to an infantry platoon as a medic. Just two and a half weeks into his tour “in country,” the Illinois native saved numerous lives when his firebase came under a savage ground attack from Vietnamese Communists. As a result of his bravery, Kays was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Kays’s real war, however, began upon his return home. Haunted by the ghosts of Vietnam, he increasingly withdrew and refused help from concerned friends and family. Sadly, he committed suicide in 1991—another casualty of the Vietnam War as surely as if he had died there. This is a heartbreaking tale of a legitimate hero who just wanted to live in peace. It should be read by all Americans to understand the peculiar plight of the combat veteran upon his homecoming.

Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military Campaigns, by Owen Connelly, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, New York, 2006, 269 pp., bibliography, index, $24.95, softcover.

Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military Campaigns, by Owen Connelly, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, New York, 2006, 269 pp., bibliography, index, $24.95, softcover.

Napoleon Bonaparte can arguably be called the greatest military commander of all time. His uncanny ability to “read” the battlefield to strategically place his cavalry, infantry, and artillery for maximum effect to assure victory was second to none on most occasions. Military historian Owen Connelly asserts, however, that Napoleon made tactical blunders at many of his famous victories. One such example came when the “Little Corporal” erred in locating Baron Karl Mack von Leiberich’s army in Germany during the Ulm Campaign in 1805. Realizing his mistake, Napoleon was forced to backtrack and engage the enemy miles away. Despite the mix-up, he was still able to achieve a stunning victory.

Miscalculations did not discourage Napoleon—quite the contrary. When he recognized his errors, he quickly improvised and altered his plans to adapt to the ever-changing conditions on the battlefield. Like a quarterback scrambling to find a receiver downfield in a football game, Napoleon became a master scrambler. “War is composed altogether of accidents,” he wrote in the waning days of his life while imprisoned on St. Helena. “A [great] commander never loses sight of what he can do to profit by these actions.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments