By Don Hollway

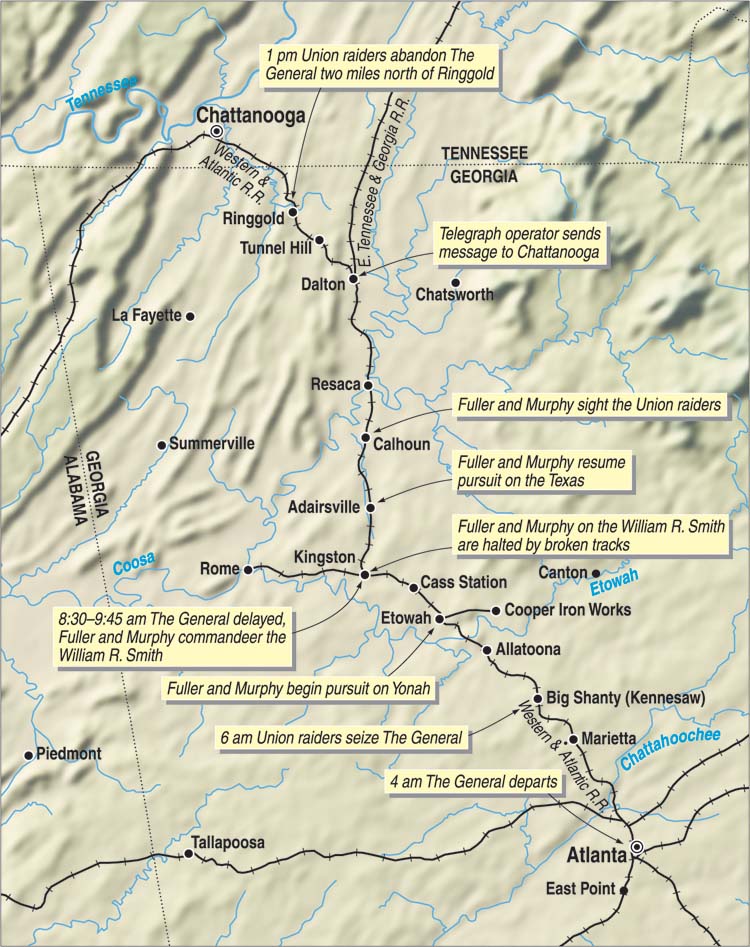

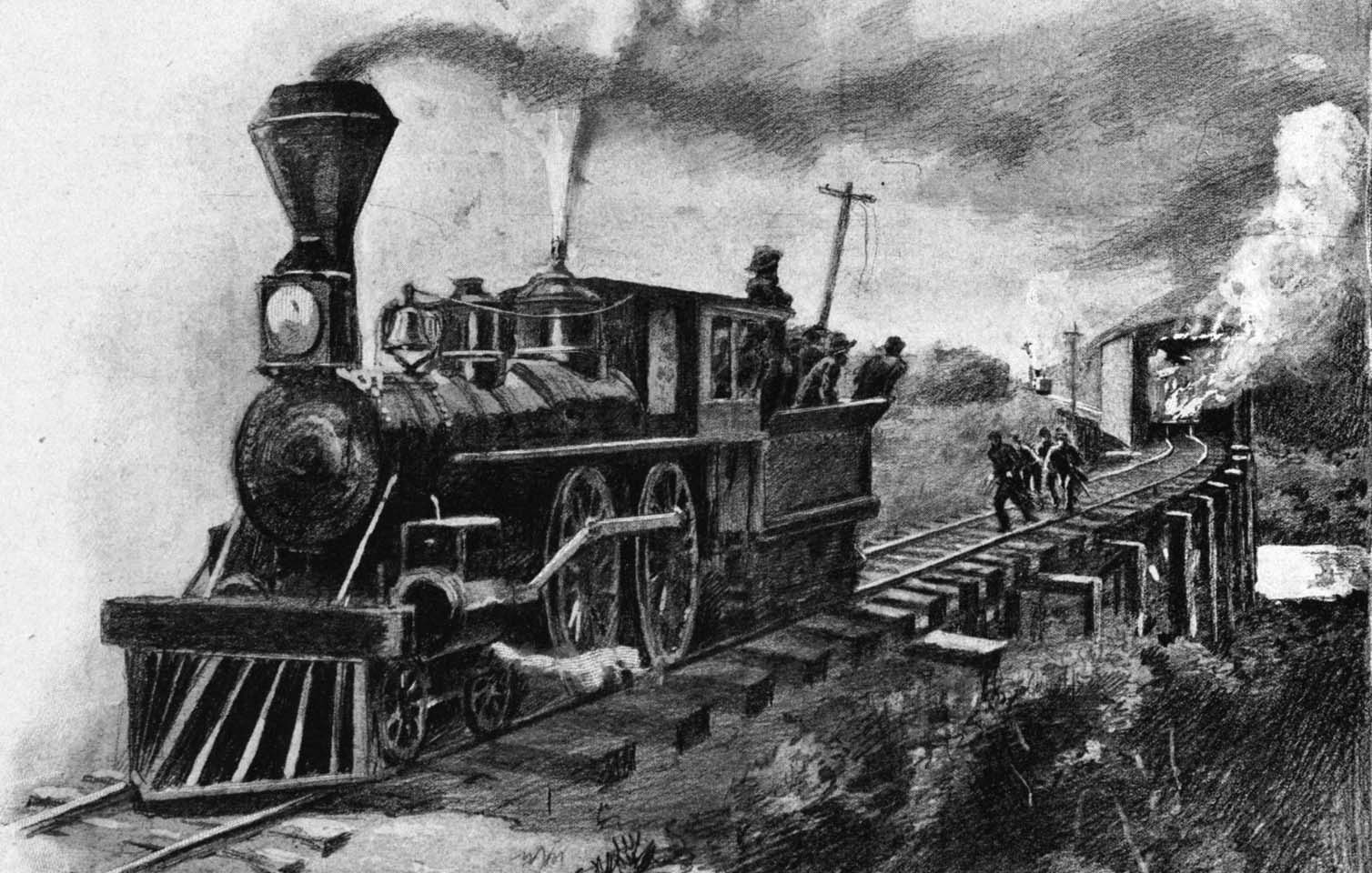

By early April 1862, the Civil War was already closing in on the South, but the trains still ran on time. When the Western & Atlantic Railroad’s Saturday morning run from Atlanta pulled into Big Shanty, Georgia, at 5:20 am, passengers had just 20 minutes for breakfast at Mr. and Mrs. George Lacy’s trackside hotel. Conductor William Fuller and engineer E. Jefferson Cain, however, had barely paid their two bits and sat down to their grits and eggs when their locomotive, The General, let out a chuff of steam and began to move. Their guest at the table, W&A foreman Anthony Murphy, shouted, “Someone is running off with your train!” Everyone bolted out of the door, too late to stop the unscheduled departure.

Fuller’s first thought was that Confederate deserters from a militia camp just across the tracks were making an escape and would likely abandon his train as soon as it ran out of steam. A train conductor, though, is the captain of his ship. A deserted, powerless locomotive blocking the way and causing tie-ups up and down the only rail line north to Chattanooga would be on Fuller’s head. “I must follow as fast as possible,” he recalled thinking, “and try to get it back before I get very badly out of time.”

Fuller was only partly wrong. It was not a handful of deserters who had stolen his train, but rather a team of 20 Federal soldiers led by a Northern spy, James Andrews. And the raiders did not plan to abandon the locomotive before they cut Tennessee off from Georgia by burning every railroad bridge between Atlanta and Chattanooga. Fuller was correct, however, in knowing that The General would quickly run out of steam—as the raiders soon learned to their distress when, a short distance out of the station, the locomotive abruptly lost power, slowed, and stopped dead on the tracks. Corporal William Pittenger, one of the raiders riding in the three boxcars stolen along with the engine, recalled the moment. “We were to have serious trouble at the outset,” he wrote later. “There had been just one burst of speed, and then this sickening and alarming failure of power.” They could only sit there, in the heart of the Confederacy, and wait for their would-be engineers to figure out the trouble.

Barely Soldiers, And No Professionals

The Andrews raiders were not train experts—they were barely soldiers. A week earlier their leader had been a mere smuggler, taking black market quinine south and information north. His volunteers were ordinary infantrymen chosen almost at random from Brig. Gen. Ormsby Mitchel’s 3rd Division of the Army of the Ohio. Only four had ever worked on a railroad; few had any experience of subterfuge, sabotage, or combat. “Never before, for so extraordinary an attempt,” one division officer observed, “was so incongruous a band assembled.”

The raiders had met Andrews on a farm outside Shelbyville, Tennessee, six days earlier. The raid, Andrews explained, was timed to coincide with Mitchel’s initial assault on Huntsville, Alabama, on April 11. Andrews issued Confederate money and ordered the men to split up, cross enemy lines by threes and fours, and catch the Western & Atlantic south over the very route they planned to destroy. “Boys, we are going into danger, but for results that can be tremendous,” Andrews assured them. “If we burn those bridges, General Mitchel can take and hold Chattanooga. But we’ll have to be prompt. The last train for Marietta leaves Chattanooga at five in the afternoon. Be sure to catch it not later than Thursday.”

“No start to a long journey could have been less promising than ours,” remembered Pittenger. “The night was pitchy dark, the rain poured down, and the Tennessee mud was now almost unfathomable.” Adding to the difficulties, enemy troops were on the alert for Federal infiltrators in civilian guise. To avoid giving themselves away, two raiders were forced to volunteer for a Confederate artillery unit defending Chattanooga. The going was so tough that Andrews, figuring the Federals could not possibly take Huntsville on schedule, delayed the mission by a day. The conspirators gathering at the Chattanooga train station were shocked to learn that Mitchel had slogged his division through the rain, after all, and had taken Huntsville by surprise that morning. “With General Mitchel in Huntsville, there would be little room to hope for our success,” recalled one of Andrews’ engineers, Private John Alfred Wilson. “It would cause the road to be crowded with trains flying from danger, and it would be difficult for us to pass them all in safety. But it was too late now to change the program. We must make the effort, come what might.”

The last train out of Chattanooga was jammed with Confederate soldiers and refugees fleeing the imperiled city. The raiders spotted numerous trains standing in stations along the way; any one of them might well block their own train the next day. They were even more disconcerted to see a large enemy training camp at Big Shanty as they passed through. Not until midnight did the train pull into Marietta. The raiders’ chief engineer, Corporal Martin Hawkins, and Private John Porter had arrived earlier and taken a room at the Marietta Hotel. Across the town square, the others crowded into two rooms at the Fletcher House to catch a few hours’ rest before an early call in the morning. “We were now almost in the center of the Confederacy,” Wilson recalled. “By the setting of another sun we might be hanging to the limbs of some of the trees along the railroad, with an enraged populace jeering and shouting epithets; or we might leave a trail of fire and destruction behind us and come triumphantly rolling into Chattanooga and Huntsville. Such thoughts as these weren’t calculated to make for sound sleep.”

Fuller Starts His Day; Andrews Calls for Last-Minute Council

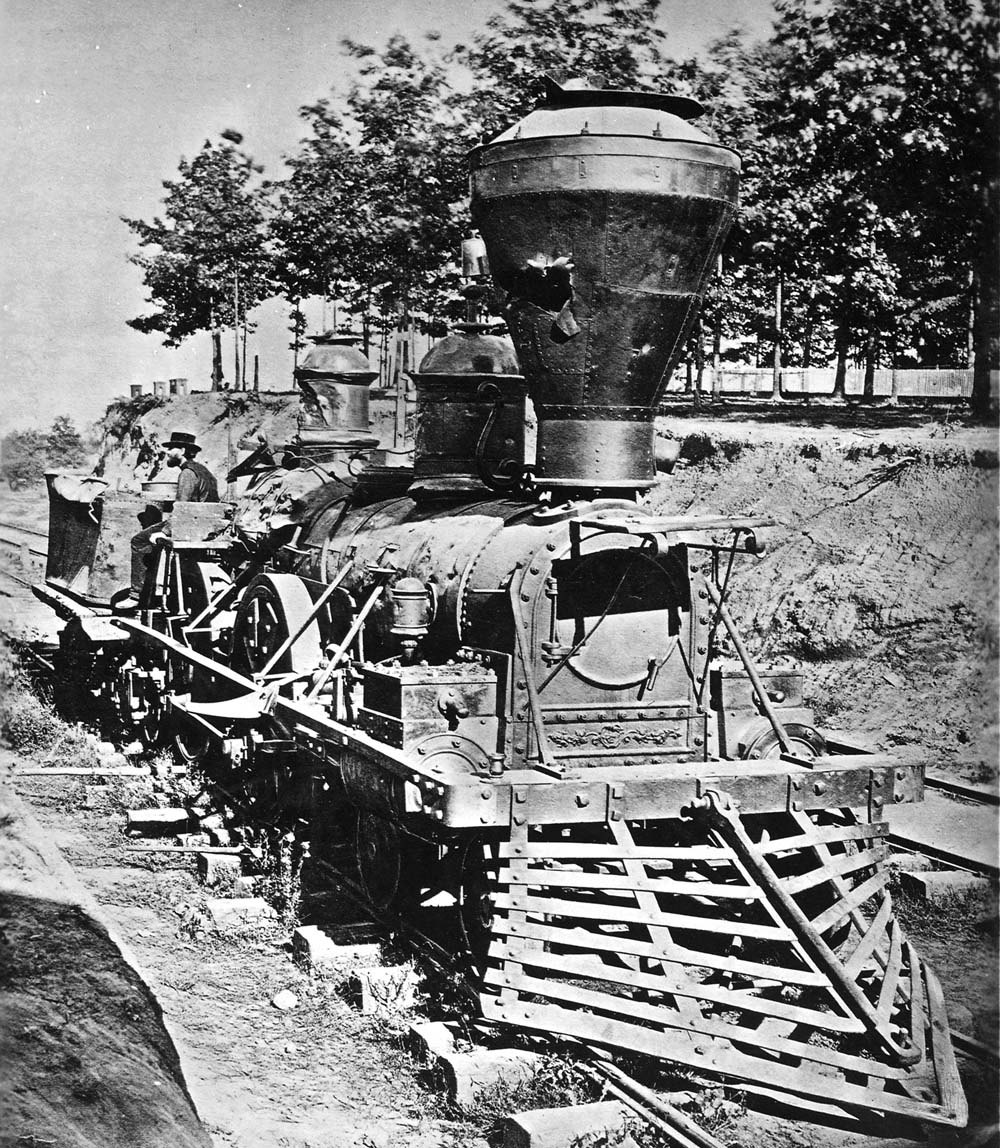

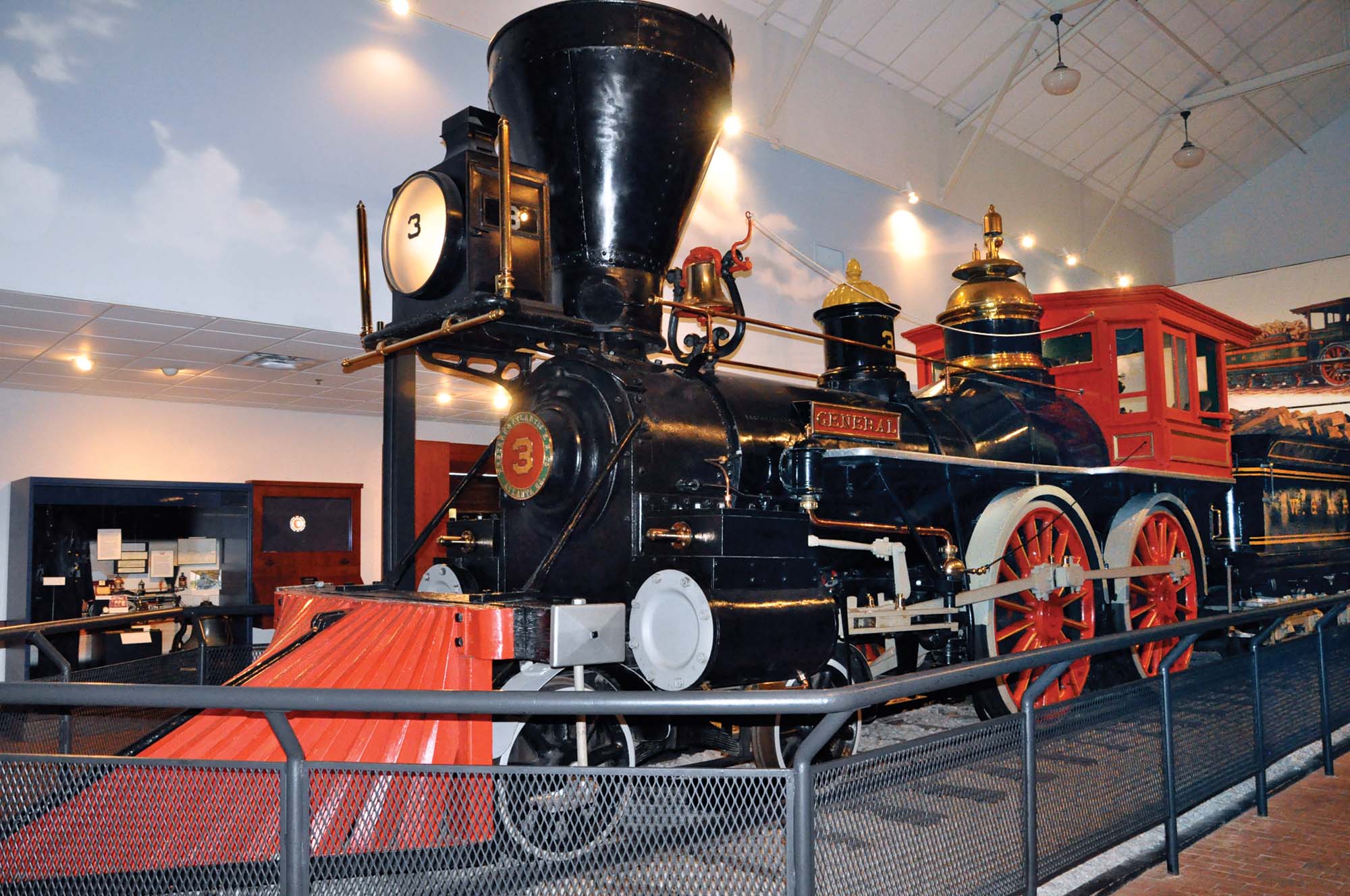

At about that same time, farther down the line in Atlanta, William Fuller was just waking up. Three days shy of 26 years old, Fuller had been employed by the railroad since the age of 19, working his way up from rail hand to flagman to brakeman to conductor. He was an ardent Southerner who, at the onset of war, had attempted to join a militia company, only to learn that railroad men were deemed more valuable at their jobs than at the front. At the train depot in the center of town, engineer E. Jefferson Cain had already warmed up their locomotive, resplendent in dark green with red wheels and piping and a gold-lettered nameplate on each side spelling out GENERAL. Its three boxcars were to be filled with surplus provisions evacuated from Chattanooga before the Federals could take the city. Foreman Anthony Murphy was headed up the line to make certain it was supplied with vital wood and water; locomotives burned a cord of wood every 35 miles. Their train pulled out promptly at 4 am for the 12-hour run to Chattanooga.

Meanwhile, in Marietta, Andrews roused his men for a last-minute council of war. “Get seats near each other in the same car, and of course say nothing of our business on the way up,” Andrews advised them. “When the train makes the Big Shanty breakfast stop, keep your places till I tell you to go. If anyone interferes, shoot him, but don’t fire unless you have to.” Any man not aboard when the signal to go was given was to be left, Pittenger remembered, “Since a delay of thirty seconds after our designs became clearly known could result in the slaughter of the entire party.”

They were already down two men. Unknown to the rest, Hawkins and Porter had failed to tip their hotel staff, who therefore neglected to give them a wake-up call. “Hawkins and Porter being left that morning was a serious loss,” recalled Wilson, “for Hawkins was the most experienced engineer of the party, and the one originally selected to take first charge of the engine.” With no time to look for them, Andrews ordered Wilson and former engineers William Knight and Wilson Brown to take over the locomotive when the time came. Some of the others wondered aloud if the mission ought to be abandoned, but the alternative was to split up and make their separate ways back to Union lines. Andrews declared that any man was free to go, but that he was carrying on with the mission. “I’ll succeed or leave my bones in Dixie,” he vowed. To a man they followed Andrews to the station, where The General was just pulling in. All found seats in the forward passenger car. They did not, however, go unnoticed. “The conductor looked narrowly at us,” recalled Pittenger, “for it was an uncommon thing for so many persons to enter in a body as we did at Marietta. It was possible, if his suspicions were aroused, that we’d have a fight in trying to take his train.”

“Come On, Boys; It’s Time To Go.”

“Deserters had been reported slipping off from the camp [at Big Shanty],” remembered Fuller, who had orders to arrest anyone boarding without a pass. But, he conceded, “On men going to the camp, as anyone from below Big Shanty would be, we weren’t keeping such a close watch.” He accepted the raiders’ tickets and moved on. Recalled Pittenger, “As we drew into the Big Shanty stop, we could see the white tents of the Rebel troops and even the guards slowly pacing their beats.” While Fuller and his men disembarked with the passengers for breakfast, Andrews and Knight stepped down on the other side, facing the camp. They went forward to confirm that the crew had vacated the cab, then came back to where the last boxcar joined the first passenger car. “Uncouple here,” Andrews told Knight, “and wait for me.” While the engineer unpinned the passenger cars, he told his men, “Come on, boys. It’s time to go.”

Wilson and Brown joined Andrews and Knight on the locomotive. The rest clambered aboard the last boxcar. “All this time a Rebel sentry was standing not a dozen feet from the locomotive,” remembered Pittenger, “casually watching, as if this were the most ordinary proceeding.” Andrews signaled Knight, and the engineer threw on full power. The drive wheels spun and screamed on the rails, but before anyone could take alarm they got purchase, and The General was off.

As the train disappeared into the distance, consternation reigned in Big Shanty. “We didn’t know what to do at first,” Murphy would recall, “but it wouldn’t do to stand there.” He sent a man on horseback to the nearest telegraph, back in Marietta, to signal the railroad superintendent in Atlanta what had happened. Meanwhile, Fuller ran the other way along the track. A soldier called after him, “What? Are you going after that train on foot?” Fuller answered over his shoulder, “Yes.” The soldier just stood and watched him go. “What a damned fool,” he said. “This seemed to be funny to some of the crowd standing around by the hotel there,” Fuller admitted later, “but it wasn’t so to me.” He called to Murphy and Cain, “Come on with me,” and in a moment all three were running down the tracks in pursuit of The General. “Knowing that we would reach a squad of track hands somewhere on the line, not far away,” Murphy wrote later, “we jogged along and had some hopes.”

Aboard the train the raiders celebrated. “This capture was a wonderful triumph,” Pittenger recalled. “To seize a train of cars in an enemy’s camp, surrounded by thousands of soldiers, and carry it off without a shot fired or an angry gesture, was a marvelous achievement. We had been told that to reach and take possession of the train would be difficult, but that all the rest of the enterprise would be easy.” They found out otherwise the moment The General lost power and stopped. Andrews and his engineers needed a long while to find the trouble. Back at the station, Cain had damped the locomotive’s firebox, and its flames had nearly died for lack of air. “The way we put in wood and poured on oil wasn’t slow by any means,” observed Wilson, who climbed atop the boxcars to see men running toward them along the tracks. Before they got in shooting range, however, the steam came up and the train lurched forward, quickly leaving the pursuers behind.

“I Ran Two And A Half Miles…”

“I ran two and a half miles,” remembered Fuller, “and when I say run, I don’t mean trot, gallop or pace. I mean run.” What the raiders did not know was that he had spent years on the railroad as a flagman, which in the early days of rail meant running ahead of a train to flag down any oncoming traffic. He had lost none of his vigor. “As I ran, I thought, and I thought as fast as I ran, and I ran as fast as I could.” Two and a half miles from Big Shanty a work gang was repairing a side switch. When the early-running half-train made an unscheduled stop and the unfamiliar crew requested tools, the workers innocently handed over a crowbar. “One of the bent, claw-footed bars, for pulling out spikes, would have been worth much more,” regretted Pittenger, “but they had none.”

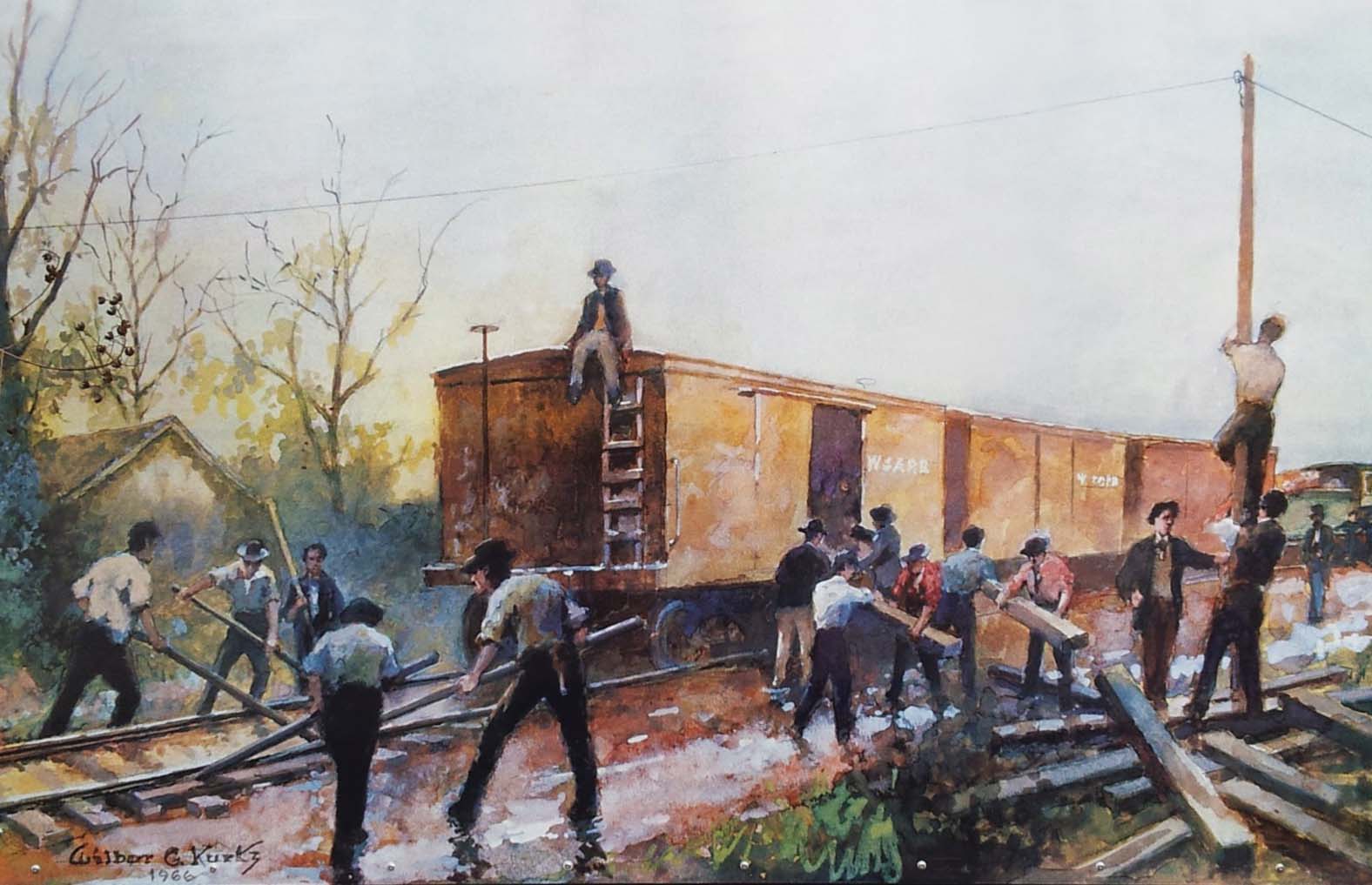

The train rolled barely out of sight before stopping again as Andrews wanted to stick to the railroad schedule to avoid running into tie-ups to the north and to prevent pursuit or alarms from the south. One raider shinnied up a trackside telegraph pole and dragged down the line to be cut. The rest dumped some of the boxcars’ load of railroad ties across the track behind the train. Once they got through Kingston junction, 30 miles up the line, Andrews assured them, “The coast will be all clear for burning the bridges and running on through to Chattanooga and around. For once, boys, we’ve got the upper hand on the Rebels.” Andrews had his engineers keep their speed down to stay on schedule, especially since they skipped regular stops at Acworth and Allatoona. “Those on the engine were very much amused, as we ran by station after station,” reported Pittenger, “to see the passengers come up with their satchels in their hands, and then shrink back in dismay as we sped past without a sign of halting.”

The raiders managed to lift a length of rail—without proper tools, no small feat even for 20 men—and load it onto one of the boxcars. At 8 am The General crossed the 620-foot bridge over the Etowah River, which Fuller regarded as “one of the best and most important bridges on the road.” Built of immense wooden trusses on five stone piers set in the river, its span would make an impassable divide; however, soaked with the continuing rains, the uncovered bridge would require time and effort to ignite. No sooner did the raiders reach the station on the north bank than they spotted a number of Confederate troops waiting for the train, not to mention another locomotive, the Yonah, sitting on a spur line. The Yonah, built in the same factory as The General, came as a complete surprise to the raiders. “We’d better destroy that,” Knight advised Andrews, “and this bridge along with it.”

Fuller Redoubles His Efforts

“It won’t make any difference,” Andrews said. As far as he knew, there was no way anyone at Etowah could have learned that The General was a stolen train, nor was there any need to get tangled in a fight. There were plenty of unprotected bridges to destroy farther north. His primary concern was getting through Kingston on schedule. “At Kingston we had more reason to apprehend danger than anywhere else on the line,” noted Pittenger. “The complicated arrangement of the switches would constitute no small obstacle. Andrews had made himself familiar with the working of the road at this point and we’d soon see how he’d overcome the hindrances in his way.”

Meanwhile, Fuller, now running ahead of Murphy and Cain, reached the work gang and learned that the “deserters” had stolen tools. “When I heard the story from the track hands,” he wrote later, “I knew it must be a Yankee trick, and from there on I was twice as sure I’d have to get my train back.” Two men helped him wrestle a handcar onto the track, push-pole back to pick up Murphy and Cain (the lever-action handcar was not yet in use), and resume the pursuit. “I fully believed that by a desperate effort I could run to Etowah Station, distant twenty miles,” he would write. “I’d take [the Yonah] in pursuit.” They manhandled away the ties dumped on the track by the raiders, picked up a pair of shotguns and two citizen volunteers in Allatoona, and were poling their way toward Etowah when they came upon the gap in the rails. Fuller and Murphy saw it coming and jumped. The rest went flying in all directions as the car left the track. One man was hurt. “Putting the car back on the rails,” recalled Fuller, “we left one of our polers here to run back and have the next section crew repair the track.”

Meanwhile, The General rolled into Kingston, her strange crew and lack of passenger cars raising eyebrows among the station hands. The old locomotive William R. Smith, on a sideline to Rome, 14 miles west, was awaiting Fuller’s passengers and mail. Andrews assured everyone that the regularly scheduled morning run from Atlanta would be along shortly and that his was a special train full of ammunition and gunpowder bound for General P.G.T. Beauregard at Corinth, Mississippi. Regardless, he had to wait for a southbound freight to pass before continuing north. While Andrews stalled and bluffed, Knight, Brown, and Wilson busied themselves with the locomotive on the siding, wary of local militia conducting Saturday morning drill on the station grounds. For the men hidden in one of the powder wagons, the wait was interminable. “To be shut up in the dark, while for all we knew the enemy might be concentrating an overwhelming force against us, was extremely trying,” Pittenger put it mildly. “But at present we had nothing to do but wait till the road was cleared for us.”

A half hour went by before the southbound freight whistled into Kingston, bearing a red flag mounted on the last car: universal warning of another train following. Now the decision to delay the mission by a day was coming back to bite the raiders. With Mitchel threatening Chattanooga, the W&A had whistled up an extra train to get all possible rail cars and supplies out of town. The General sat idling on its siding for the better part of an hour until the second freight rolled in. On it, too, to the shocked dismay of Andrews and the other raiders, was another red flag. Its conductor explained there had been too many outbound cars in Chattanooga for one locomotive to pull, so the train had been split in two. “Had Andrews taken the risk of running out in the face of the first extra, we might already have made the first station above,” remembered Pittenger, “[but] it would be insanely rash to try running out between two sections of a belated train. It was better to wait, even if that entailed the risk of a fight.”

“Let Them Have It Hot and Fast”

About this time, Fuller, Murphy, and their handcar crew rolled into Etowah to commandeer the Yonah and Confederate reinforcements. “Getting an open car and stocking it with some rails, spikes and tools, to repair the track if needed,” reported Murphy, “we pushed on, pressing the Yonah hard.” Up ahead, the Kingston workers were beginning to look suspiciously on the tall, bearded stranger in command of the unscheduled train. Andrews had promised the regular mail run was following close behind, but it had failed to arrive. Nor had any telegraph signals from the south announced a change in the schedule, for the line was dead. Loudly complaining that this was no way to run a railroad and that his train should have been given priority, Andrews sent Knight back to the men in the boxcar. “Boys, we’ve got to wait a while for one more train that’s behind time, and the local folks are getting mighty uneasy and suspicious,” Knight told them. “Be ready to jump out, if you are called, and let them have it hot and fast.”

Andrews, carrying an ivory-handled revolver, hovered near the telegraph station in case the operator reached for the key. Finally, however, the third freight arrived. Andrews immediately ordered it out of his way, demanding that the station’s switch keys put his train back on the main line. The old yardman in charge refused, demanding to know by what authority everyone was being ordered around. The raiders in the boxcar could hear the shouting. They tensed for a fight. Andrews laughed in the man’s face: “I’ve no time to waste with you, old fellow,” he said. Fetching the switch keys off the wall, he went up and changed the tracks himself and, while the yardman threatened to have him arrested, waved The General onward. The raiders rolled out of Kingston an hour and five minutes after they arrived—a mere four minutes before the Yonah, with Fuller and Murphy and 20 soldiers aboard, rolled in from the other direction.

The tangle of trains blocked them as surely as a broken track. Fuller went to the front of the pack to take over the William R. Smith from the Rome line. The train quickly filled with militiamen, infantrymen, and railroad men eager to join the chase. “We had no control over this crew,” Murphy lamented. “Everyone was wild, the engine was small, with very low driving wheels, and there were several cars loaded with people, so that we made slow time and I feared the day was lost.”

The raiders had to make Adairsville in time to get around a regularly scheduled southbound freight and yet another passenger train, but first had to stop and cut the track behind them. The failure to burn the bridge at Etowah or disable the Yonah, the long fruitless wait at Kingston, none of it would matter if they cut the telegraph and rails, blocking any chase behind and any alert ahead. “We still believed ourselves an hour ahead of any possible pursuit; but we wanted very badly to pass the two trains still before us and hurry to our real work of bridge burning,” recalled Pittenger. They cut the wire and the rail was giving at the southern end when in the distance they heard, faintly but unmistakably, the whistle of a northbound locomotive. “It could only be in pursuit of us,” Pittenger observed, “and no sound more unwelcome ever fell on human ears.”

Yet Another Foot Race

In the moment it took the William R. Smith to reach the spot, the raiders were gone, having actually broken the rail before leaving. By now Fuller needed more than that to stop him. “Having neither tools to work with nor time to delay,” he recalled, “I abandoned the engine and called for volunteers to join me in another foot race. When I’d run a half mile or so, I looked back. Anthony Murphy was the only man following me.” The pursuers knew that their quarry would meet with delays at Adairsville, five miles north, and they expected to cut them off before they could leave.

As Fuller expected, the locomotive Texas, at the head of the regular southbound freight, was waiting on the Adairsville siding for The General, now a half hour behind schedule. Its conductor swallowed Andrews’ ammunition story but reminded him of the passenger train still ahead. “Get through by all means,” he said, “but you’ll have to run very slow and put a flagman on every curve, or you’ll have a collision.” Andrews had done enough waiting. He had to beat the oncoming train to the next stop at Calhoun, then cut the line again farther north to leave all the trains trapped behind The General. “Let’s see how fast she can go,” he told his crew. “We’ll want every second we can save between here and Calhoun.”

Knight, Wilson, and Brown had been waiting all morning for that order. They poured on such steam that the locomotive nearly jumped out from under the men in the boxcar. “The engine,” remembered Pittenger, “seemed to be not so much running as coursing with great lionlike bounds along the track.” The wheels threatened to leave the track as The General wound up to top speed, between 60 and 70 miles per hour. Said Pittenger, “We tumbled from side to side like grains of popcorn in a hot frying pan. I shudder when I reflect on that, my first and last locomotive ride. We took little thought of the matter then. Death in a railroad smash-up would have been preferred by us to capture.”

The locomotive Catoosa was just pulling out of Calhoun when they came roaring in. Its engineer hastily backed to let The General pass onto the siding, but his train was so long that its trailing cars blocked the raiders’ way back onto the main line. Despite a detachment of the 1st Georgia Infantry on hand, Andrews almost drew his revolver. “I must press on without delay,” he said. “Pull your engine ahead and let me out.” Finally clear, he and his men waved to the bewildered crowd at the station. “We were on the main track with no train between us and Chattanooga,” recalled Pittenger. “We had passed five trains—the achievement the greater since all but one had been either extras or behind time. The Oostanaula Bridge [at Resaca] was just ahead, and when that was burned, our program seemed pleasurably simple. We’d sail along from bridge to bridge, firing them as we passed.”

Reaching Calhoun 10 Minutes Behind the Raiders

Meanwhile, the Texas, proceeding south from Adairsville, met Fuller and Murphy running north. As soon as they hopped aboard and explained the situation to engineer Peter Bracken, he threw his train into reverse and dropped their cars on the Adairsville sideline. Running backward with just its tender, the Texas—every bit the equal of The General—reached Calhoun 10 minutes behind the raiders. They didn’t even come to a complete stop, but took aboard 17-year-old telegraph operator Edward Henderson, sent down from Dalton to find the break in the silent wire. As the Texas steamed out, the Catoosa cut loose from her cars, took on a dozen or so of the Georgia soldiers, and followed.

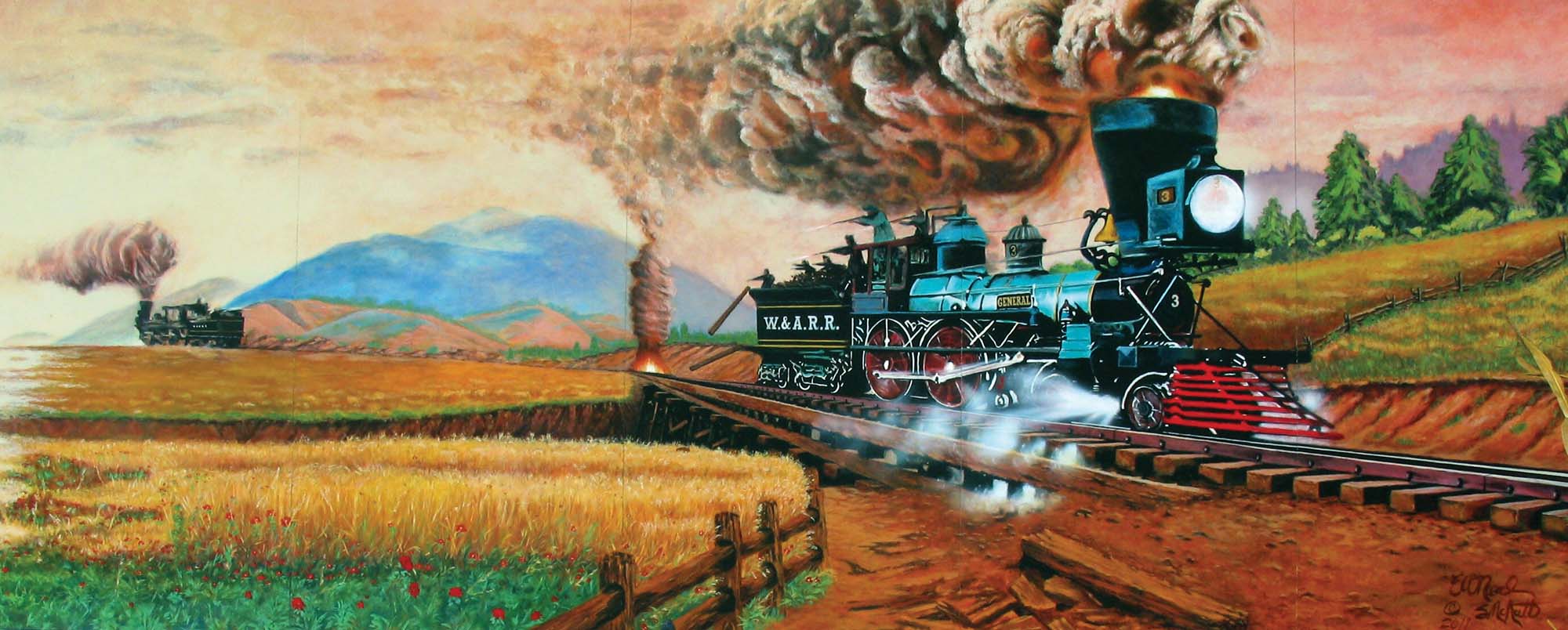

“About three miles above Calhoun,” recalled Murphy, “we came in sight for the first time of the captured engine and the freight cars.” The raiders had paused again to cut the wire but hadn’t completely pried up a rail when they heard the Texas whistle. “By the sound, it was near and closing in fast,” noted Pittenger. “The coming of the Texas, before the track above Calhoun was torn up, was by far the most serious misfortune we had yet encountered.” Forced to leave the loose rail in place, Andrews put no faith in it stopping the oncoming train. He cut his last boxcar loose and left that in the way as well. Had the Texas not been running in reverse, the ploy might have worked: the weight of the car might have crumpled its cowcatcher down until it snagged the track and perhaps even nosed the locomotive off the rails. Instead, feeling their way backward across the loose rail, Fuller and his crew simply picked up the stray car and pushed it along in front of them.

Having cut rails and wire all along the way, the raiders could not imagine how word of their stolen train had caught up with them. It never occurred to them that a conductor at Big Shanty, starting out on foot, could close within minutes of their speeding locomotive. They thought it more likely that word had reached south from Big Shanty to the telegraph station at Marietta, then up to Chattanooga and back down again. If that was true, Pittenger reasoned, “Our race was almost run. We would be obliged to leave the railroad, and try the far more difficult task of escaping on foot.”

Yet they might still complete their mission of burning at least one bridge if they could slow or halt their pursuers. They knocked a hole in the rear of the second boxcar and began tossing ties out onto the track. Such was their speed that many simply bounced end over end, off to the side. Enough remained across the rails to slow the pursuit, but not to give them time to stop and fire the rain-soaked covered bridge at Resaca. “Had the day been dry, we could have flung fagots from the engine upon the roof,” Pittenger despaired, “but now a fire even on the inside of the large frame bridge would require careful nursing.” Instead, they cut loose the second, empty, useless boxcar, but Fuller and the Texas simply scooped it up and dropped it along with the first on a siding just beyond the bridge. Said Pittenger, “The time lost in dropping the cars was about as long as that in coupling to them.”

By now, Fuller’s blood was up. “From the instant we got over the bridge at Resaca, the race became one of life or death between the two engines, throttles wide open. No such race has ever been run, either before or since.”

“Those after us had one of the best locomotives on the road,” said Wilson, “and a fresh supply of wood and water, while we had but little of either, our supply having nearly run out. We crammed the furnace with every combustible we could lay our hands on.”

Would Andrews Try to Fight?

Tired of the stop-and-go chase, some of the soldiers urged Andrews to “let our engineer take our engine on out of sight, while we hid on a curve after putting a tie on the track, and waited for the pursuing train to come up; then, when they checked to remove the obstruction, we could rush them, shoot every person on the engine, reverse it, and let it drive back at will as it came.”

“The chances of a battle were certainly against us if Andrews had attempted to fight,” Murphy conceded later. “He had better than twenty well-armed men, and we were just seven, with two rusty shotguns.” Andrews didn’t know that. He had seen the Georgia infantry ready to board at Calhoun, and he had no way of knowing they were still several minutes behind the Texas on the Catoosa. For that matter, he was no battle commander—he was a saboteur, there to burn bridges. “Nothing against the man,” Knight said of him later, “but I don’t think he was intended to take charge of lot of men in a case like that.”

“None of us said anything more about this plan [to fight],” said Pittenger, “partly because we felt that our leader was better able to judge what was to be done than we, and partly because we thought he was only waiting for the place to turn on our pursuers, and that we would soon have all the fighting we wanted.” The next bridge was far up the line past Dalton, the junction of the Western & Atlantic with the East Tennessee & Georgia Railroad—an even bigger tangle of branches, sidings, and switches than the tie-up at Kingston. “If anything delayed our immediate passage through this station,” Pittenger worried, “serious difficulty could arise. We might have a battle.”

The General stopped 100 yards short of the Dalton depot. Andrews ran ahead alone to check the setting of the switch, telling onlookers, “I am running this train through to Corinth and I have no time to spare.” No one tried to stop him. He ran back, and The General took off through the station at such speed that a station hand remarked its engineer would surely be fired for it. “Here was the only instance, I think,” Wilson said in hindsight, “where we failed to do all that could have been done. We ran about two minutes too long before we stopped to cut the wire.”

As the Texas sped into town, Fuller dictated a message to telegraph operator Henderson for Brig. Gen. Danville Leadbetter, commanding the Confederate defenders in Chattanooga: “My train was captured this am at Big Shanty, evidently by Federal soldiers in disguise. They are making rapidly for Chattanooga, possibly with the idea of burning the railroad bridges in their rear. If I do not capture them in the meantime, see that they do not pass Chattanooga.” If they got that far, the raiders might well accomplish their mission. Henderson leaped off the Texas, skidded into the telegraph station, and fired off the message. Atop a pole two miles north of town, the raiders cutting the wire might have felt the dots and dashes speeding through their fingers. In Chattanooga, the message broke off before completion, but enough information came through for Leadbetter to send several flatcars loaded with Confederate infantry 11 miles down the W&A, where they tore up the track, emplaced cannons, and waited for the stolen train and its thieves to appear.

Down To Their Last in Wood & Water

Aboard The General, the raiders were realizing reluctantly that they would never reach Chattanooga. They had thrown their last tie out the back of their last boxcar, were down to the last of their wood and water, and were losing steam. And now the Texas was in sight behind them. “Our situation,” as Wilson put it laconically, “was becoming more unpleasant every moment.” Their last hope was to burn one of the bridges over the winding Chickamauga River, just beyond the 1,447-foot tunnel through Chetoogeta Mountain. “If Andrews was disposed to fight,” believed Pittenger, “[the tunnel] was the place of all others to do it. With the smoke of our train filling the space, with our party concealed along the sides in the darkness, success would be likely even if they had twice our number.”

The men on the Texas were alert to the danger. They entered the tunnel slowly, peering ahead in the gloom for broken tracks or a stopped train. But by the light from the far end they soon saw that not only was the track unbroken, but The General was gone, leaving hardly any smoke in the passage. The raiders were clearly almost out of fuel. Fuller cried, “Boys, we’ve got ’em now!” Again proving himself more adept at sabotage than soldiering, Andrews had hurried the train through the tunnel to the first bridge over the Chickamauga, telling the men to begin firing their last boxcar. Pittenger remembered, “The rain fell in torrents, and the wood in the tender was drenched. We tore everything combustible loose from the car, and smashed it into kindling.” Another raider added, “We set fire in the last boxcar to the remaining ties, and also some rubbish thrown in for the purpose, and tried hard to get up a good blaze. The rains had so soaked everything that this seemed impossible, and our fire burned aggravatingly slow.”

The General came to a full stop at the Chickamauga bridge, which was large and well covered with timber. “Inside, it was at least drier than on the outside, and with time the bridge timbers might be made to burn,” Pittenger wrote. “The car which, if the day had been dry, would have filled the bridge with a mass of flame, was burning faster than the bridge.” Wilson recalled, “We had no more than fairly got to work before we saw the black smoke of the pursuing locomotive. Our most strenuous efforts to place distance between ourselves and our pursuers had been in vain. Our race was almost run.”

The Chickamauga bridge was too wet to burn, and they would never reach another. “Our fire was sufficient to smoke us out of the car onto the engine and now empty tender,” recalled a raider, “but not sufficient for the now impractical task of firing a bridge even if we could reach it.” The General, with the Texas now just a few hundred yards behind, labored north of Ringgold but finally gave out on the upgrade beyond the village. At 12:30 pm, 61/2 hours and 88 miles from Big Shanty, Andrews gave his last command to his men: to jump off one by one, scatter in the woods, and attempt to work their way back to the Union lines. “We all left the engine at Andrews’ order,” said one of the raiders, “except Knight and Brown, who stuck to her until the last of us jumped off; then, with a sudden jerk of the lever, they reversed it and jumped themselves.”

Hungry, Unprepared, Wet And Lost

The men on board the Texas saw the raiders bound off into the woods, and The General with its still-smoldering boxcar rolled back down at them. As he had twice before, Engineer Bracken simply matched speeds and caught the runaway train on his tender. Murphy boarded The General and found her little the worse for wear. Meanwhile, the Catoosa came up behind and unloaded her troops. The Great Locomotive Chase was ending as it had started—on foot.

The raiders all eventually made it to Chattanooga, though not as planned. Hungry, unprepared, wet, and lost, most were captured in short order. With the aid of a compass, Andrews led two others to within 12 miles of the Union lines before they were caught. Hawkins and Porter, who had “volunteered” for the 9th Georgia Infantry Battalion at Big Shanty, were soon exposed. The first eight raiders, including Andrews, were put on trial, convicted as spies, and sentenced to death. Andrews’ sentence was carried out first, at 5 pm on Saturday, June 7, near the intersection of Juniper and Third Streets in Atlanta. The hanging was horribly botched: the cotton rope stretched and Andrews’ feet touched the earth. A guard had to swing the doomed man’s struggling body off to the side and hold it there as another scraped away the ground while Andrews slowly strangled. William Fuller was in the crowd and witnessed the whole thing. Ten days later, he saw seven more raiders hung en masse at Fair Street (now Memorial Drive) and South Park Avenue in the city.

The trials of the other raiders were delayed by the war, and they eventually escaped. Brown, Knight, and Hawkins reached Federal lines to the north. Wilson floated down the Chattahootchee River to the Mississippi and was picked up in the Gulf of Mexico by a Federal gunboat. The rest were recaptured, including Pittenger, and eventually returned in prisoner exchanges. All survived the war, becoming the first recipients of the newly minted Medal of Honor. As a civilian, Andrews was ineligible for the honor.

After the war, both sides of the Great Locomotive Chase held mutual reunions until 1906, a few months after Fuller passed away. The last of the participants died in 1923. Their famous locomotives outlived them. The Texas currently resides in the Atlanta Cyclorama Building in Grant Park, and The General, having come full circle, is now the pride of the Civil War museum at Kennesaw, Georgia, former Big Shanty. Andrews and the other executed raiders are buried at National Cemetery in Chattanooga, where a granite monument, donated by the State of Ohio in 1890, is topped with a bronze replica of The General. It is frequently visited by schoolchildren, who like to look at the scale-model train, even if they are somewhat confused by the tragic history behind it.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments