By Arnold Blumberg

For the Federal government at Washington, D.C., the news from Tennessee was grim in late September 1863. The Union Army of the Cumberland, under Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, had been surprised and defeated at the Battle of Chickamauga and bottled up inside the city of Chattanooga, facing starvation and ultimate capitulation. Reacting to this severe and unexpected military setback, Abraham Lincoln on September 24 transferred part of the Army of the Potomac (about 20,000 men) by rail to aid the beleaguered Federals in southeast Tennessee.

It was not until October 1 that General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, was able to confirm the suspected transfer of sizable enemy forces from Virginia to Tennessee. Eager to go back on the offensive after his shattering defeat at Gettysburg three months earlier, the Confederate leader was determined to do so even though his effective force of 46,000 men was greatly outnumbered by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s 85,000-man Army of the Potomac. By attacking, Lee hoped to prevent the transfer of additional Federal troops to the West and force another battle on his opponent at better advantage than the misbegotten three days at Gettysburg.

If Lee was keen to move forward, his chief of cavalry, Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart, was virtually obsessive about it. His controversial role in the Gettysburg campaign had seriously tarnished the “Bold Dragoon’s” reputation as an effective mounted commander. More and more, the opinion of the public, the government, and the army itself was that

Stuart’s failure to provide adequate cavalry support during the battle was the root cause of the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg. Without saying it in so many words, Lee seemed to subscribe to the same viewpoint. He reorganized the army’s cavalry, expanding the mounted arm from a single division to a corps of two divisions under Maj. Gens. Wade Hampton and Fitzhugh Lee.

Officially, the overhaul was said to promote efficiency by providing better command and control, but unofficially it was designed to reduce Stuart’s control by allowing senior cavalry officers such as Hampton and Lee to exercise more initiative during operations. The fact that Hampton and Lee were elevated to major general and Stuart was not made a lieutenant general—the normal rank for a corps commander—underscored the real reasons for the reorganization and the degree of disfavor into which Stuart had fallen.

The politically canny Stuart, who had gloried in his nickname “the Beau Sabreur” since his famous “Ride Around McClellan” in 1862, was well aware of the real reasons for the changes to his command. He wanted to show to everyone—beginning with the revered Robert E. Lee—that he was not past his prime as a leader of men or a combat tactician. Stuart eagerly embraced Lee’s plan for an assault on Meade as a way to restore confidence in both himself and his troopers.

Lee intended to advance from Madison Court House around his opponent’s right flank, gain his rear, and force Meade to attack the Confederates on ground of Lee’s choosing. The plan was essentially a rehash of the one Lee had attempted to carry out during the summer of the previous year. Then the Union Army of Virginia, under the boastful Maj. Gen. John Pope, had been positioned between the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers. On that occasion, the design was wrecked when Pope pulled back across the Rappahannock at the last minute to avoid Lee’s trap. Now Meade was in almost the same position that Pope had occupied. The Bristoe Station campaign began.

While 7,000 Confederates (two infantry and three cavalry brigades) pinned down approximately 25,000 Union troops along the northern bank of the Rapidan, Lee hurled the rest of his army against the Federal right upstream. Leading the advance was Stuart, personally leading Hampton’s 2,500-man cavalry division. (Hampton was absent from the army recovering from injuries sustained during the Gettysburg campaign.) The rest of Stuart’s troopers, under Fitzhugh Lee, carried out a diversionary assignment along the south shore of the Rapidan.

Fitz Lee, a nephew of the army chief, was a 37-year-old graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, class of 1856. After service on the Indian frontier after graduation, Lee had been appointed an assistant instructor of tactics at the academy. He joined the Confederate mounted arm in 1861, and by August 1863 he had advanced to the rank of major general. At Stuart’s side during almost every cavalry enterprise Stuart conducted, Lee was regarded as one of the best leaders of horse in the Army of Northern Virginia. His bravery, skill, and ability to act independently made him an outstanding battlefield officer.

Stuart’s mission was twofold: to move ahead of the infantry columns of Lt. Gens. Richard S. Ewell and Ambrose P. Hill, screening their advance and keeping tabs on enemy strength, movements, and dispositions. Alert Federal scouting parties had detected Confederate preparations for just such a turning maneuver by October 7. In response, Meade had strengthened his northern flank with cavalry supported by infantry, a total of more than 9,000 men.

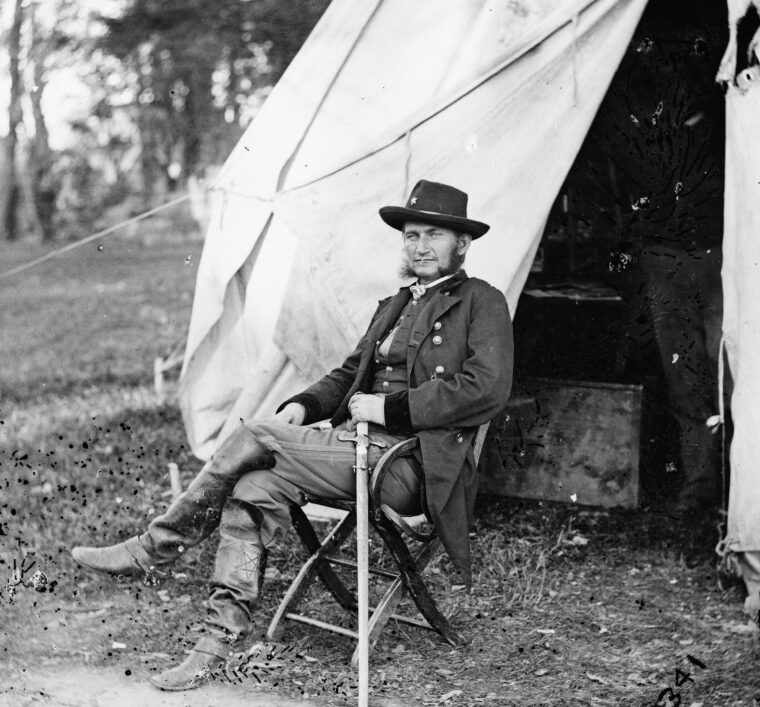

The Confederate offensive commenced at dawn on a chilly October 10, with Stuart’s force marching northeast of Madison Court House. Facing Stuart during the first days of the campaign were Brig. Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick and his 3rd Cavalry Division, which had been given the tasks of delaying the Rebel advance and discovering their true intentions. Kilpatrick was a 27-year-old native of New Jersey and graduate of the United States Military Academy, class of 1861. After beginning his service as an infantry officer, he moved to the cavalry branch in 1862 as lieutenant colonel of the 2nd New York Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. Kilpatrick participated in several successful mounted raids in northern Virginia and was instrumental in safeguarding the retreat of Pope’s defeated army after the Battle of Second Manassas. His pursuit of Lee’s retreating army after the Battle of Gettysburg was both vigorous and well conducted.

While recognized as a bold leader of horsemen, Kilpatrick elicited not so flattering opinions about his personality. A Confederate recorded that he had a “weasel face and a cruel and vile disposition.” One of Meade’s aides described the young brigadier as a “spare, nervous, jerky man.” Others commented on his womanizing, penchant for self-promotion (he had a newspaper reporter permanently assigned to his staff to record his exploits), and utter recklessness in the presence of the enemy. Indeed, Kilpatrick’s insouciance over losses among his men and horses had earned him the less-than-fond sobriquet, “Kill Cavalry.”

The initial Confederate advance fell on outposts manned by troops in Kilpatrick’s 1st Brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. Henry E. Davies. Educated at Harvard and Columbia, Davies at the commencement of the conflict had been practicing law in New York City. He had commanded the 2nd New York Volunteer Cavalry, and then on Kilpatrick’s recommendation had been given charge of 1st Brigade, 3rd Cavalry Division. When Davies was promoted to brigadier general, he was one of the few nonprofessional soldiers to obtain that rank in the Union cavalry corps. The former attorney was eager to prove his worth as a commander of horse soldiers and did so by mirroring his patron Kilpatrick’s careless, brash ways. Davies seemed capable enough when closely supervised by his superiors, but on his own he tended to act on impulse and not clearly evaluate situations—unfortunate traits for any military commander.

After crossing Robertson’s River, Stuart’s men held the attention of the Union pickets of Davies’s brigade, supported by infantry, while more Confederate cavalry gained their rear, capturing 90 enemy soldiers and forcing Davies to retreat. The next day, Kilpatrick also retreated to the outskirts of Culpeper Court House, closely followed by Stuart. Meanwhile, the infantry of the Army of the Potomac fell back across the Rappahannock River. To the southeast, the Union 1st Cavalry Division, under the capable Brig. Gen. John Buford, moved to link up with Kilpatrick, closely followed by 12 mounted regiments under Fitzhugh Lee.

Facing Kilpatrick’s 3,500 troopers with only 1,500 men, Stuart eschewed a frontal assault on his numerically superior opponent and instead raced hard to turn his enemy’s right flank in the vicinity of Fleetwood Heights, the scene of the climactic cavalry fight at Brandy Station on June 9. Quickly deducing Stuart’s purpose, Kilpatrick swung his regiments around to the rear and made for Fleetwood Heights. For the next 20 minutes, the commands of Stuart and Kilpatrick, in plain sight of each other, pounded up converging roads toward the same destination. Meanwhile, Fitz Lee directed his brigades to change direction and attempt to get behind Kilpatrick and cut him off from escaping across the Rappahannock River.

As Kilpatrick and Stuart hurtled toward the heights, their men delivered a number of saber charges and countercharges. This allowed Buford to reach Fleetwood Heights first, closely trailed by Brig. Gen. Thomas Rosser’s Confederate brigade, which positioned itself to block Kilpatrick’s juncture with Buford. Colonel E.B. Sawyer, leading the 1st Vermont Volunteer Cavalry, later reported: “The scene began to grow interesting. We were not only flanked on both right and left, and closely pressed in the rear, but right across the road we desired to travel we were confronted by a strong force. We were surrounded.”

Kilpatrick’s division approached Brandy Station, with the 2nd Brigade under Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer in the lead. The 23-year-old Custer was also a graduate of West Point, class of 1861. Although he had been the class goat, he had proven himself a brave and active staff officer and found favor with the commander of the army’s cavalry force, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton. On June 29, 1863, on Pleasonton’s recommendation, Custer had been promoted from brevet captain to brevet brigadier general, taking charge of the 2nd Brigade, also known as the Michigan Brigade because it comprised the 1st, 5th, 6th, and 7th Michigan Regiments.

The elevation to brigade leader had seemed justified when Custer performed capably during the Gettysburg campaign and the numerous cavalry contests waged along the Rappahannock River during the subsequent summer and fall. Although he reveled in mounted saber charges, usually leading them himself, Custer also demonstrated unexpected skills in dismounted tactics, using his troopers’ seven-shot carbines and rifles to deadly effect. Exceedingly brave if oddly attired, Custer looked, said one bemused observer, “like a crazy circus rider.” Unlike Kilpatrick, however, he was also generally careful of his soldiers’ welfare. They, in return, idolized him.

Approaching Brandy Station, Custer ordered his troopers to punch through the enemy cordon and link up with Buford. As the brigade band struck up “Yankee Doodle,” Custer led the 1st and 5th Michigan into the attack (the 6th and 7th were detailed to ward off the Confederates who were pressing the brigade’s rear). After four furious mounted assaults, he broke through, enabling the 3rd Division to join Buford on the heights. While Custer was achieving his success, Davies, on Custer’s right, was fending off a determined Confederate attack on the division’s left.

Meanwhile, Buford exhibited his well-known steadfastness, unflappability, and hard fighting by resisting all efforts to drive him off Fleetwood Heights. In a calculated and well-timed move, Buford sent one of his brigades under Colonel Thomas C. Devin to strike Fitzhugh Lee and relieve some of the pressure on Kilpatrick. (Not surprisingly, the official reports later submitted by Kilpatrick, Davies, and Custer make no mention of the aid Buford’s actions rendered in making the breakthrough by the 3rd Division possible.) Fighting continued for two more hours, with regiments and squadrons attacking and being attacked from all directions. Although surrounded by Stuart’s graybacks, the Federals held Fleetwood Heights until 7 pm, when they slipped back over the Rappahannock to safety.

The two sides had lost approximately 400 men killed, wounded, captured, or missing. But while the Federals could take great satisfaction in the way they concentrated their commands and stood firm on Fleetwood Heights, the same could not be said for their opponents. Stuart was quite frustrated that, after hours of pursuit and battle against a surrounded enemy, his prey had gotten clean away. He had missed a golden opportunity to eliminate two-thirds of the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry in one fell swoop. The fight on Fleetwood Heights was another in a string of defeats and humiliations suffered by the Southern horsemen throughout the summer and fall of 1863.

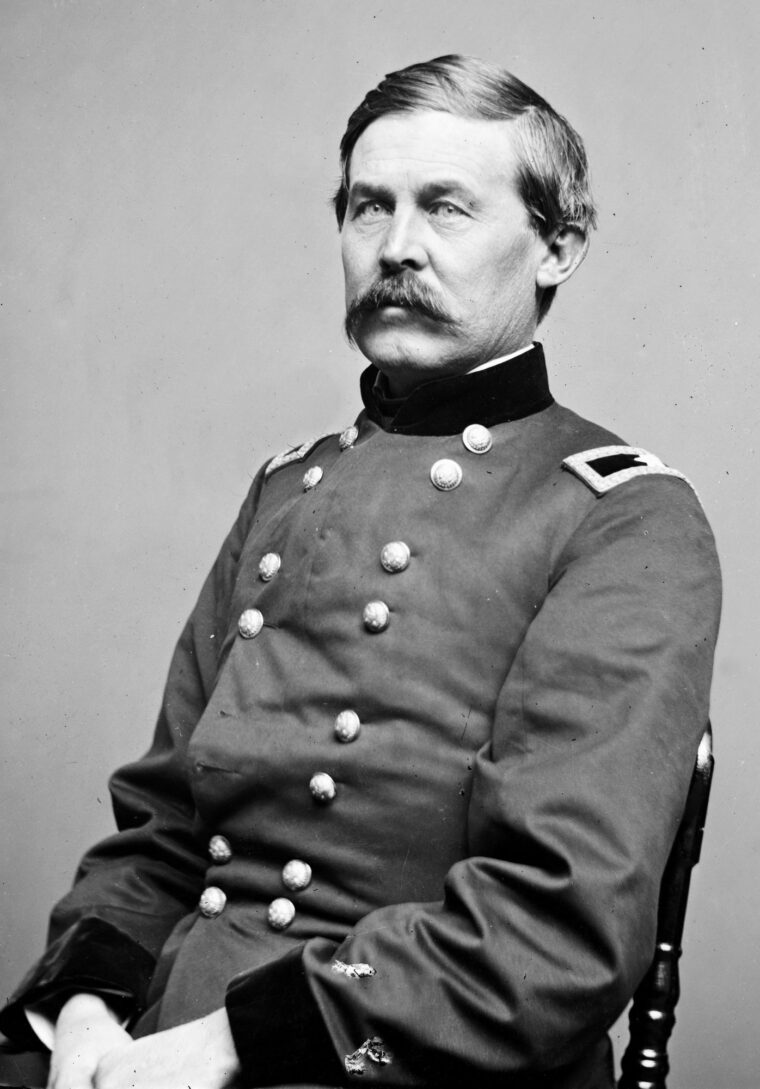

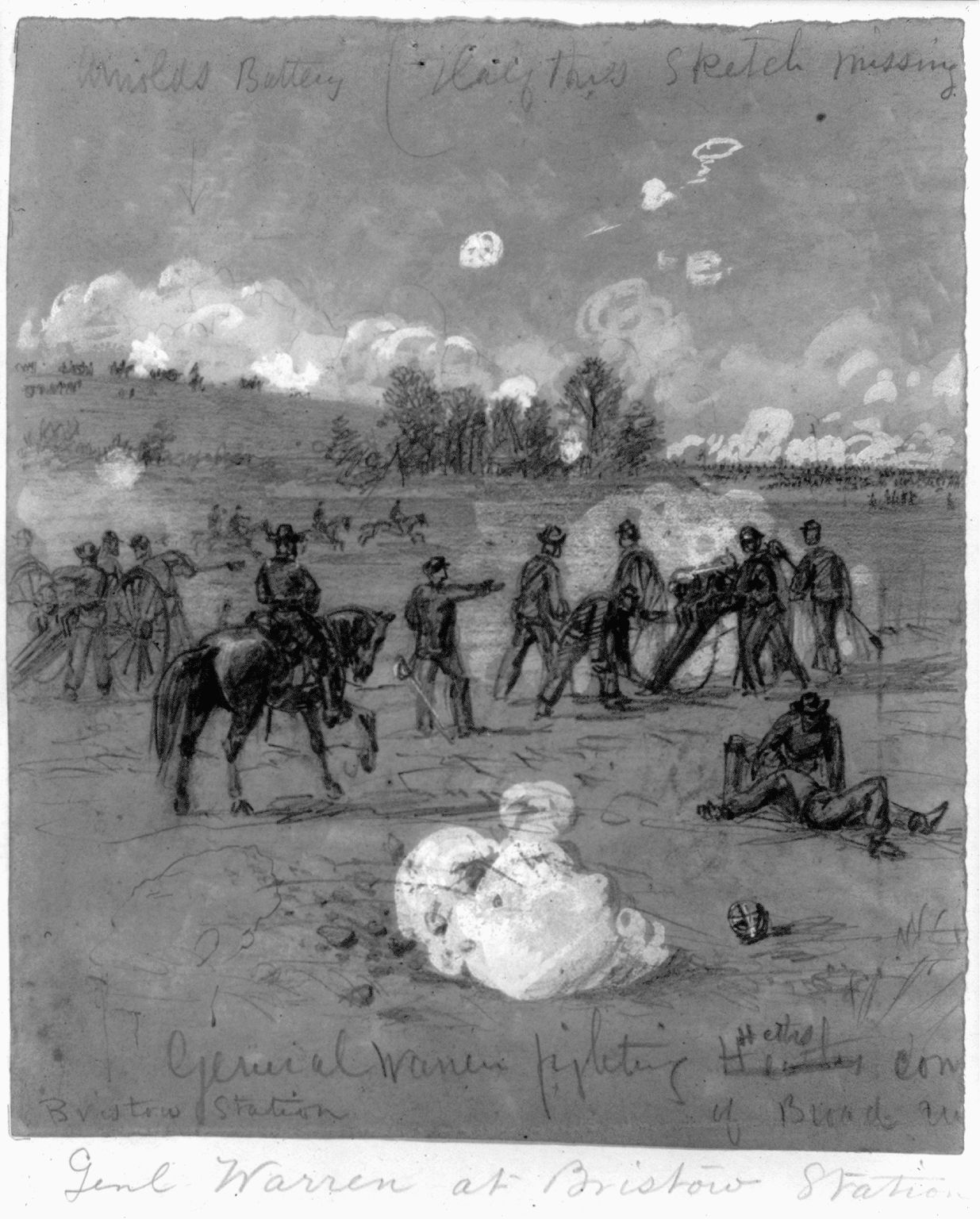

Over the next several days, Union reconnaissance uncovered Robert E. Lee’s move to flank the Army of the Potomac and reach the town of Warrenton in the Union rear. Meade reacted by pulling his entire army back 30 miles to Centreville, taking up a strong defensive position. The 14th saw the only pitched battle involving opposing infantry of the Bristoe Station campaign when the Confederate III Corps under Ambrose Powell Hill made a piecemeal attack against Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s II Corps. Hill was forced to retreat after losing 1,500 men to the Federals’ 500.

By October 18, Meade was entrenched north of Bull Run Creek, while Lee’s army concentrated around Manassas Junction. Strain on the Confederate logistical situation forced Lee to pull back toward the Rappahannock to be nearer his base of supply. Learning of the Confederate retreat, Meade ordered a pursuit to start the next day. At the time, Stuart was closest to the Union army, having camped at Gainesville. Fitzhugh Lee was about five miles to the southwest at the village of Auburn. Kilpatrick’s command had skirmished with Stuart throughout most of the 18th in the vicinity of Groveton and Gainesville and farther north at Haymarket. The day ended with both sides facing each other in front of Gainesville.

At dawn on October 19, Kilpatrick received orders to move as quickly as possible toward Warrenton, 12 miles to the west. Pleasonton admonished his subordinate to send out patrols to locate the enemy, but strangely did not make the same demand for reconnaissance parties on Kilpatrick’s southern wing. Furthermore, only Kilpatrick’s division was directed to pursue the Confederates; Buford and Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg were issued no orders to probe for the retiring foe. Instead, they were directed to look after the army’s wagon trains near Bull Run Creek. Pleasonton assumed that any Confederate horsemen would be preoccupied with guarding the passage of the infantry over the river.

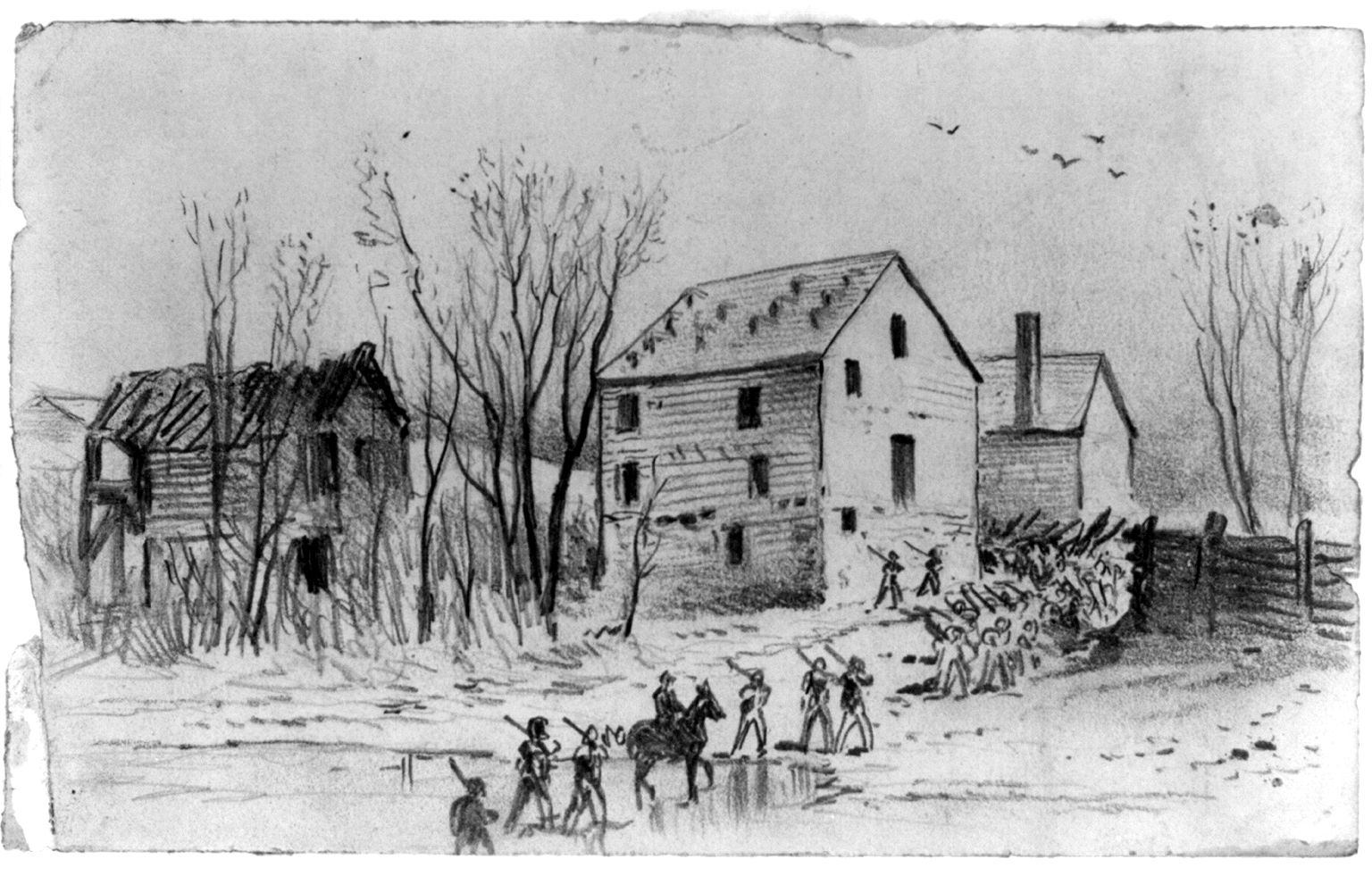

Kilpatrick apparently shared his superior’s opinion of the situation. He sent out a few small scouting parties to locate Stuart, but these failed to find the main force, which had moved before dawn from Gainesville to the west bank of the rain-swollen Broad Run at Buckland Mills, four miles to the west. The sloppy performance by the Union scouts was aided and abetted by the heavy rain that fell throughout the early morning hours, the ankle-deep mud making mounted movements slow and difficult.

Stuart, for his part, planned to keep Kilpatrick’s force in check long enough for Fitz Lee to come north and join him on the Broad Run. Custer’s troops pushed back pickets in Brig. Gen. Pierce M.B. Young’s brigade, but failed to force a passage at Broad Run. Brig. Gen. James B. Gordon’s North Carolina brigade dismounted and skillfully delivered effective small-arms fire at their adversaries from the south bank of the creek. In response, Custer dismounted three regiments of his own command, keeping the 1st Michigan mounted and ready to exploit any breakthrough.

As the two sides blazed away at each other, Custer rode with his staff to a position in the road where his men—and the Confederates—could see him. His effort was rewarded by a well-placed Confederate artillery shot that exploded in their midst. Custer’s famous luck held—no one in the party was killed or wounded. Taking the hint, Custer and his group moved off to a less-exposed spot.

Seeing that the Tarheels could not be dislodged, Custer changed tactics, moving around the Confederate flank. About noon, he managed to pass over to the south shore.

Stuart was not concerned about Custer’s belated success. He now had an alternative plan to hold the Broad Run position. During the fighting, he had received a reply from Fitzhugh Lee to Stuart’s request that Lee come north to support him. Lee countered with a more imaginative idea: he suggested that Stuart intentionally withdraw slowly, thus allowing Lee to head north and strike the Federals in the flank and rear. Lee calculated that Kilpatrick’s well-known impetuosity would aid in the success of the ambush. Stuart agreed and moved his brigades toward Warrenton at a leisurely pace. When Stuart heard Lee attack the Federals, he would quickly reverse direction and assault the enemy frontally.

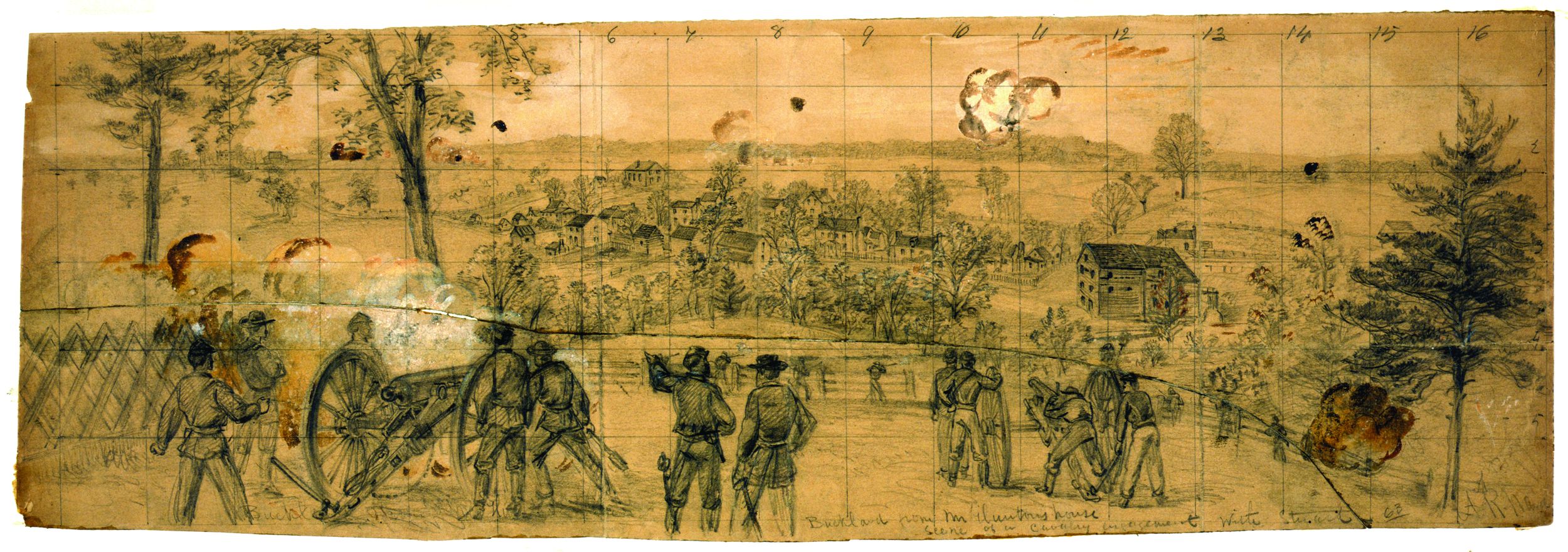

Stuart led Gordon’s, Young’s, and Rosser’s units along the broad Warrenton and Alexandria Turnpike until they reached a range of slightly rising ground known locally as Chestnut Hill, 21/2 miles northeast of Warrenton. Stuart arrayed his columns behind the high ground. Young’s and Rosser’s men remained in the road, while Gordon had his troopers dismount and file into fields adjacent to the highway. A thin line of mounted skirmishers took up positions on the forward slopes of Chestnut Hill to guard the deployment. Gordon joined Stuart, and the Confederates waited for their Union counterparts to appear.

Around noon, Davies, accompanied by Kilpatrick, arrived at Buckland Mills. Founded by Samuel Love in 1774, the crossroads village soon became a trading post and added a woolen factory, wheelwright, and shoemaker. To accommodate travelers, two taverns were opened. By 1835, the town was thriving as a stagecoach stop and the site of two productive flour mills, an inn, and distillery. Located on the main road connecting Alexandria and Warrenton, the local population had as yet avoided the hard hand of war.

After Davies entered the town, he was ordered to pass through Custer’s men and take the lead in the chase of Stuart. Custer was told to follow Davies. Kilpatrick then set off with the 1st Brigade, expecting the 2nd Brigade to follow shortly. The division commander was intent on overtaking the enemy and seemed unconcerned with what lay ahead. In his haste, Kilpatrick took only the most perfunctory precautions to secure his flanks and rear as he hurried after Stuart.

With Kilpatrick gone, Custer ignored his directive to move out along the road to Warrenton. Instead, he had his command unsaddle their mounts and feed them as well as themselves. He later explained that he had done so because his brigade had been marching and fighting all morning and had not had time to eat or rest. Perhaps the Boy General had a premonition of the trouble that would soon descend on Kilpatrick’s command and wanted to avoid it. Whatever the reason, Custer’s reluctance to join the hunt for an allegedly fleeing enemy was distinctly out of character.

While Custer stood down his command, Davies’s advance stumbled upon Confederate scouts a mile west of Buckland Mills. He pushed them back two miles to the crossroad at New Baltimore. There, on instructions from Kilpatrick, Davies left a holding force and pressed on to Warrenton. Approaching Chestnut Hill about 3:30 pm, Davies heard artillery fire coming from the direction of Buckland Mills. He quickly surmised that Custer might be in trouble.

Davies was right. Custer had been attacked by Fitzhugh Lee, who had come up from Auburn like a thunderbolt. After Kilpatrick and Davies left, Custer had ordered his men to prepare, rather leisurely, to follow the rest of the 3rd Division. Fortunately for him, Custer had also taken the precaution of sending the 7th Michigan toward the hamlet of Greenwich to the south and placing the 6th Michigan to guard the stone bridge over Broad Run. After making these arrangements, Custer finally moved out, taking with him the 1st and 5th Michigan, the 1st Vermont, and the horse artillery. He left the 6th and 7th Michigan behind where he had placed them.

No sooner had Custer left Buckland than the men in the 6th Michigan noticed Rebel riders moving through the woods to the south. Captain Don G. Lovell, riding alongside Major James Kidd, shouted, “Major, there is a mounted man in the edge of the woods yonder!” A puff of smoke appeared from the man’s pistol, and a bullet buried itself in the chest of one of Kidd’s horses. He immediately ordered his men to dismount and take cover behind a stone fence bordering the turnpike. The attackers were from Colonel Thomas H. Owen’s brigade, which had slipped by unnoticed by the scouts sent out from the 7th Michigan.

Hearing the exchange of gunfire between the 6th Michigan and Owen’s Virginians, Custer turned back to Buckland Mills. Upon arrival, he formed his regiments in a line facing south near the bridge over Broad Run. The 1st Vermont formed the left of the line, with the 5th and 7th Michigan falling in on the right. The 1st Michigan acted as a mounted reserve and supported Lieutenant Alexander C.M. Pennington’s battery of six 3-inch rifled guns. The 6th Michigan was thrown out ahead as skirmishers.

Facing Custer was Fitzhugh Lee’s entire division, whose own battle line overlapped the Union position. Many of the Confederates were carrying infantry rifles, thus leading Custer to report later that he had been attacked by infantry. As the Southerners advanced, they were aided by the fire of a friendly artillery unit, Captain James Breathed’s 1st Horse Artillery, which quickly caught the attention of Pennington’s gunners, who returned fire over the heads of their comrades in the 6th Michigan. As the firefight intensified, the Confederate line extended across the turnpike, cutting off any aid that might have been forthcoming from Davies’s column, three miles to the west.

The spirited engagement lasted about an hour before enemy pressure and threat of encirclement convinced Custer to retreat. Covered by the 1st Michigan, the rest of the brigade broke east over the Buckland Mills bridge. Pennington limbered up and raced off just as the Confederates came within 20 yards of his pieces. The 1st Vermont followed in the battery’s wake. In the hasty retreat, Custer lost his headquarters wagon containing his personal papers, some of which were published—much to his embarrassment—in Richmond newspapers.

A dismounted battalion from the 5th Michigan under Major John Clark was unable to reach the bridge before it was overtaken by the Confederates. He and a part of his unit were captured, while others in the regiment managed to escape by plunging their horses across Broad Run under heavy fire. Fitzhugh Lee pursued Custer as far east as Gainesville before both sides went into bivouac for the night.

While Custer fought against overwhelming odds at Buckland Mills, Davies had to deal with his own crisis. His command had pushed on toward Chestnut Hill, and according to one Confederate eyewitness, it was a sight to behold: “As far as the eye could reach their column of splendidly equipped cavalry was marching on with flags fluttering and arms glittering in the bright autumn sunshine.” The Federals had reached a point 200 yards from the Confederate defenders when the boom of artillery rolled across the countryside from the direction of Buckland Mills. This was the signal that Stuart and his men had been waiting for. Gordon’s brigade immediately formed on the turnpike and moved toward the enemy.

Spearheading the Southern assault was 41-year-old James B. Gordon of North Carolina. Gordon, a college-educated merchant, farmer, and politician, had entered the conflict as an enlisted man, rapidly rising in rank to colonel of the 1st North Carolina Volunteer Cavalry and then to brigadier general of the North Carolina Cavalry Brigade. A protégé and kindred spirit of Stuart, Gordon was a born soldier: competent, aggressive, full of nervous energy, and widely admired by his men and the rest of the army.

Taking its place in the pike, Gordon’s unit was flanked on the left and right by Young’s and Rosser’s brigades. Sabers were drawn. Mounted skirmishers on both wings were exchanging fire with the Federals, who appeared ready to charge. Stuart, standing next to Gordon, told him to advance quickly along the turnpike and strike the enemy before they could attack. Gordon rode to the front of his column, found Major Rufus Barringer, commanding the 1st North Carolina Cavalry, and ordered him to hit the Federals in his front. “Major Barringer,” he said, “charge that Yankee line and break it.”

Barringer obeyed at once and led his regiment, first at a trot and then at a gallop, down the road. As the pace quickened and the bugles sounded the charge, the men let go a loud Rebel yell. The sound of pounding hooves and Confederate artillery was deafening as the Tarheels closed to within 50 yards of their target. They met scattered mounted pistol and carbine fire from the 2nd New York Regiment, which now formed the rear guard of Davies’s column while the balance of the force headed back east toward Buckland Mills. The 2nd New York did little harm to the onrushing Rebs. They did not attempt to countercharge—a fatal mistake for cavalry being attacked by other cavalry—and soon were fleeing in all directions before the Confederates could close with them at sabers’ reach.

Reforming his lines, Barringer continued the chase, encountering broken groups of the enemy a mile outside New Baltimore. Barringer went into the Federals with a vengeance, and according to Gordon broke them in “great confusion and pursued for several miles with unrelenting fury.”

With the situation deteriorating rapidly, Kilpatrick ordered Davies to reinforce the 2nd New York with the 1st West Virginia Cavalry and hold off Stuart while the rest of the brigade headed northeast for Haymarket via Thoroughfare Gap. With the 2nd New York running, the 1st West Virginia could do little by itself to stem the gray tide. After Kilpatrick had his horse, Lively, shot from under him, Davies told every man to save himself. With that, all order in the Federal regiments dissolved and the mad dash for Broad Run began.

As the Federals fled, the Confederates passed through New Baltimore (where Barringer was thrown by his horse) and Haymarket, routing the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry and gathering up retreating bluecoats by the dozens as they went. The pursuit did not halt until the Confederate horsemen encountered Union infantry under Colonel Edward L. Dana of the 143rd Pennsylvania Regiment near Haymarket.

Kilpatrick, riding a borrowed horse, galloped back to Gainesville, where he reunited with Custer. That night, a somewhat chastened Kill Cavalry invited his officers to headquarters, where he “made a sorry attempt at merrymaking which did not serve to take away the bad taste left by the affair, especially among the officers of the 1st Brigade.” Kilpatrick later conceded that he suffered a setback, “the only cavalry victory the enemy can boast over my command.”

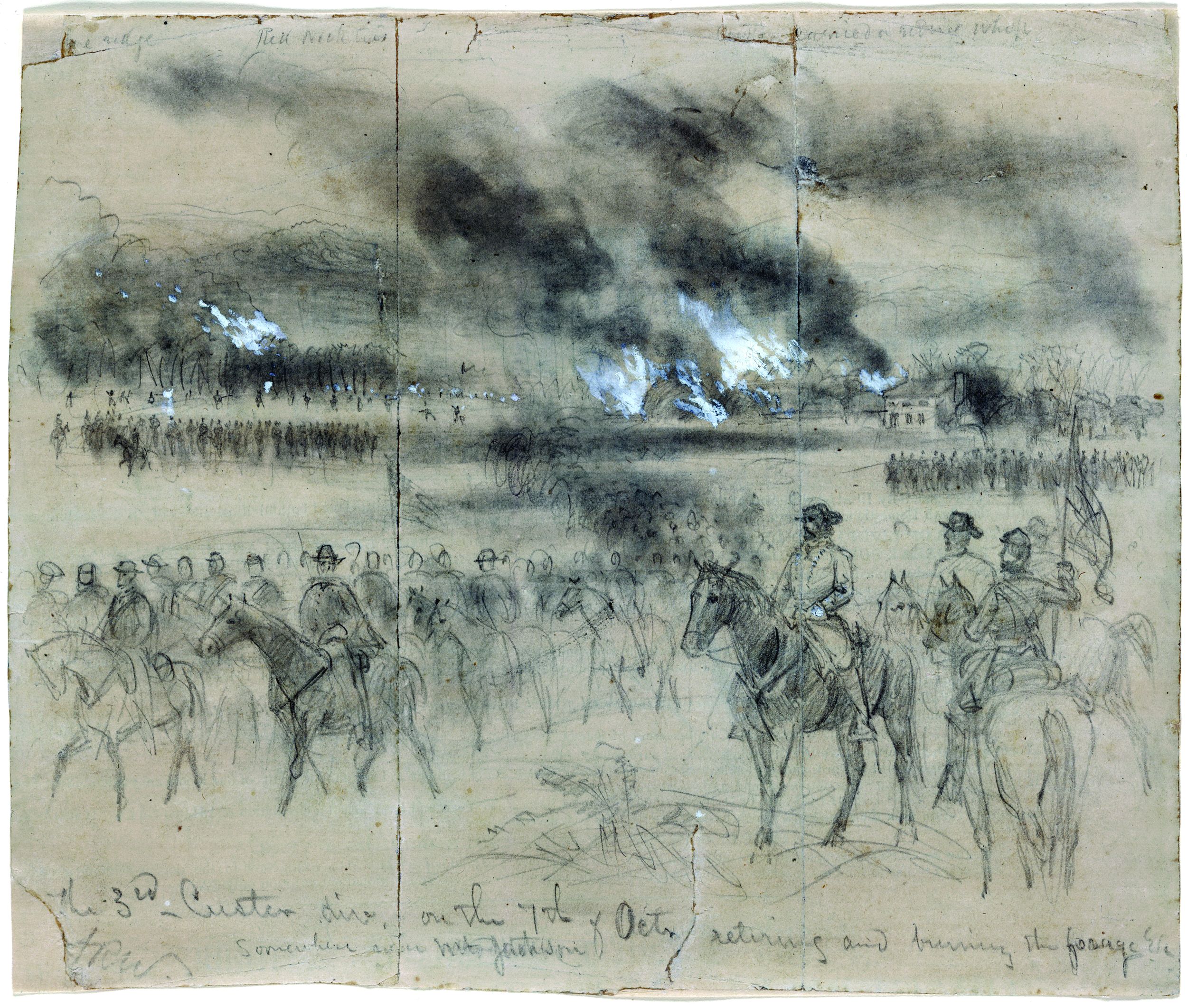

A delighted Stuart was quick to make that boast, reporting the capture of 377 Union prisoners on October 19. His own losses did not exceed 60. “The rout of the enemy at Buckland,” he said with some exaggeration, “was the most signal and complete that any cavalry has suffered during the war.” Davies counted his brigade’s losses at 102 killed, wounded, or missing. Custer reported losses of 214 men (and uncounted letters).

The engagement at Buckland Mills was instantly dubbed the “Buckland Races” by delighted Southerners, who termed it a true Virginia steeplechase. It was the last battle of the Bristoe Station campaign, and, although no one realized at the time, it was also the last victory J.E.B. Stuart would gain over the Union cavalry before his death at Yellow Tavern, Virginia, seven months later.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments