By Blaine Taylor

According to the 1960 memoirs of Henriette Hoffmann von Schirach, Adolf Hitler called Father Josef Tiso, a monsignor in the Roman Catholic Church and premier of Fascist Slovakia, “The little parson.” CBS radio broadcaster William L. Shirer described Tiso as being “almost as broad as he was tall” in his book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

Dr. Paul Schmidt of the German Foreign Office recalled, “It was strange to see Hitler greeting this Catholic priest with friendliness; the short, stout Catholic dignitary stood facing a man who could hardly be called a friend of the Catholic Church, but when Tiso wanted something for Slovakia, he would have visited the devil himself. He once told us, ‘When I get worked up, I eat half a pound of ham, and that soothes my nerves.’”

Frau von Schirach, former wife of Hitler Youth leader Baldur von Schirach, painted a vivid word portrait of the rotund little priest at home and at ease in his native Slovakia during the war: “Two thousand children were evacuated to Slovakia. While we toured the country with Tiso, the fat little clergyman told us the primitive local legends. He told the driver to stop at the ruins of a fortress where Bluebeard had ‘bathed in the blood of virgins.’ Tiso wanted us to remember Slovakia as a wildly romantic country.”

Father Tiso was one of a trio of unusual men, two of them priests, who together helped deliver Slovakia into the fold of the Axis Pact as Nazi Germany’s first ally in Central Europe, even before Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano signed the Italo-German Pact of Steel on May 22, 1939, at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.

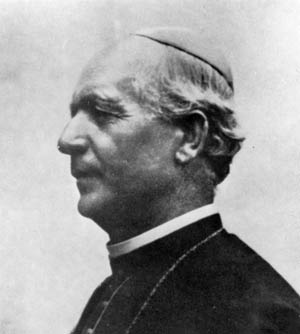

The other priest was Father Andrej Hlinka, and the two were joined by a law professor and founder of the Hlinka Academic Guard, Vojtech Bela Tuka, the Fascist Slovakian prime minister. Both Monsignor Tiso and Professor Tuka harkened back to the initial efforts of the third man, Father Hlinka, a priest, social activist, and politician who, in 1913, founded the Slovak People’s Party. In October 1918, Father Hlinka was a co-founder of the Slovak National Council and a signatory of the Declaration of the Slovak nation. The following month, he also established the Catholic Cleric Council and then recreated the Slovak People’s Party, whose chairman he remained until his death.

Hlinka had originally been a strong supporter of ethnic unity within the new state of Czechoslovakia, but he grew bitter as he witnessed the influence of his Catholic Church being limited. He had long been a fighter for both independence and the Slovak language and was chief editor of the movement’s newspaper for many years. One of his closest associates was Father Tiso, a chaplain in the Hungarian Army during World War I.

The Hlinka Academic Guard (HAG) was a name given to the Hlinka Academic Club in 1938 in honor of Father Andrej. Considered anti-German, the HAG was disbanded in July 1940, when the Nazis demanded that its commander, Jozef Kirschbaum, be ejected from Slovak political life.

There were two main factions in the People’s Party. The conservatives were represented by Hlinka, and after he died by Tiso and Karol Sidor, leader of the paramilitary Hlinka Slovak People’s Party, who both wanted limited independence within the Czechoslovak Republic. Tuka came to represent the radicals who wanted a total break from the Czechs. He worked with the German separatists of the Sudeten German Party and also desired close ties with Poland.

On August 4, 1933, Father Hlinka read out his Nitra Declaration on the sovereignty of the Slovak nation and met with Sudeten German Party chief Karl Hermann Frank in a joint effort to destroy the Czech state.

As leader of the radical wing of another right-wing group, the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party, Dr. Tuka was to prove a strong ally of the more powerful and longer lasting of the three men responsible for the creation of the Slovak state, Father Tiso.

The future president of Slovakia, Father Tiso was born on October 13, 1887, at Velka-Bytec, Slovakia, then part of the old Dual Monarchy ruled by Austrian Kaiser Franz Josef I. Tiso was the son of upper middle class Slovak peasants, which for a millennium had been oppressed by the Hungarians, who viewed them as serfs. Thus, he and the pro-Hungarian Tuka were rather odd political bedfellows.

At the time of Tiso’s birth, the Slovak language was banned in most public institutions and there was but a single library, as opposed to 3,000 under the later Czech Republic that he helped destroy. Initially, Tiso engaged in pro-Hungarian, anti-Slovak activities, but in 1918 he joined the Slovak Peoples Party, a conservative Catholic organization whose program was reactionary but not yet openly separatist, when the Prague Republic was formally created on October 30 of that year.

Young Tiso had attended the Hungarian high school at Nitra, where he reportedly fawned over his Magyar superiors and was thus placed in the Catholic priesthood by the local Hungarian prelate, was ordained in 1909, and the next year became secretary to the Bishop of Nitra. He also became an instructor at a girls school and then chaplain to the rich village of Banovce.

Recalling the former Czech promises made regarding Slovak autonomy in 1918, many Slovaks felt betrayed when these were not kept. Father Hlinka’s People’s Party highlighted their grievances, and it was thus to it that Tiso gravitated in time.

Tuka.

Father Tiso was elected to parliament at Prague in 1925, the same year as Dr. Tuka. He supported the Republic while there, but attacked the Czechs back home in his electoral district. The next year, the portly priest was named minister of health in a coalition government, working closely with Dr. Tuka.

In August 1938, Tiso delivered the eulogy at Monsignor Hlinka’s funeral and, in effect, assumed the leadership of his party. The conclusion of the Munich Pact of September 30, 1938, gave Tiso the opportunity to demand more autonomy for Slovakia within what was left of the overall republic. He coerced the Czech government in Prague to grant permission to form an autonomous Slovak government in Bratislava within the jurisdiction of the Federal Republic. Tiso became prime minister of the new government in the autumn of 1938.

At the Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg in September 1938, Hitler had trumpeted, “I want no Czechs!” In fact, he was already plotting how to seize both the capital city of Prague and its two rich provinces, Bohemia and Moravia. He contemptuously referred to what remained of the republic as “Czechia” and the “Rump Czech State.” His key to destroying what had been created in 1918 was to split off from it the Independent State of Slovakia, and in this grand design both Drs. Tiso and Tuka played starring roles.

As early as October 14, 1938, Hitler sneeringly told the new Czech Foreign Minister Frantisek Chvalkovsky that the British and French guarantees of his country’s frontiers were worthless. Three days later, Luftwaffe Field Marshal Hermann Göring received Slovak leaders Alexander Mach and Deputy Prime Minister Ferdinand Durcansky, and they told him that Dr. Tiso’s new government wanted, in fact, to break away from Prague.

willing accomplices as Father Tiso moved

Slovakia closer to the Nazi orbit.

As a result, Göring noted privately, “A Czech state minus Slovakia is even more completely at our mercy. Air base for Slovakia for operations against the east very important.”

On the 21st, Hitler gave orders for a military plan to be drawn up for the invasion of Czechia. As these preparations went forward, the Führer received Dr. Tuka at the Reich Chancellery. Although he was meeting a foreign leader, Tuka addressed Hitler as “My Führer,” adding, “I lay the destiny of my people in your hands. My people await their complete liberation by you.”

This was exactly what Hitler wanted to hear, and he told Tuka that he would help if Slovakia would move to aid itself. An overjoyed Dr. Tuka later called it “the greatest day of my life.”

Prague reacted during March 9-10, 1939, when Federal President Dr. Emil Hacha dismissed Dr. Tiso’s government at Bratislava. The next day, he also ordered the arrests of Tiso, Tuka, and Durcansky, proclaiming martial law throughout all of Slovakia. Hitler and Göring had been caught flat-footed, but on the 11th an angered Führer decided to force the issue and take Bohemia and Moravia by ultimatum.

Meanwhile, Hacha had replaced Monsignor Tiso with Sidor, who took office as president. During his first cabinet meeting, Karol Sidor was called upon by Nazi leaders Artur von Seyss-Inquart and Gauleiter Josef Buerckel and five German Army generals demanding that he proclaim Slovakian independence immediately, or else Hitler would wash his hands of their fate.

Meanwhile, Father Tiso had escaped from house arrest at a monastery and accepted an invitation from Berlin to see the Führer at once. Locked up, the prelate had telegraphed Hitler for help and had been answered. While awaiting Monsignor Tiso’s arrival, Hitler had dispatched 14 German divisions to the new Czech frontier, thus vastly increasing international tension. Gauleiter Buerckel told Tiso that if he had refused the Führer’s invitation two of these divisions would have crossed the border, occupied Slovakia, and then divided it between the Reich and Regent Miklos Horthy’s Hungary.

At 7:40 pm on March 13, 1939, Tiso and Durcansky arrived at Hitler’s sumptuous new study at the Chancellery. The Führer was flanked by High Command Chief General Wilhelm Keitel and Army Commander-in-Chief Col. Gen. Walther von Brauchitsch. Hitler bluntly told the little parson to accept Slovak independence under German military protection or else. Tiso did so, sending a Nazi-drafted telegram declaring independence and asking for Reich armed aid, which was duly granted. The next day Dr. Hacha, also summoned to Berlin, signed away under duress his country’s survival, and Hitler entered Prague.

observances of the fifth anniversary of the

Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, Father

Tiso leaves a Czech cathedral.

Noted the 1943 edition of Current Biography: “On March 18, 1939, Tiso signed a pact with Hitler in Vienna in which Nazi Germany guaranteed to protect the boundaries of Slovakia for 25 years, and in return received complete domination of the country. Slovakia, with an area of 14,386 square miles and a population of 2,450,096 has been drastically Nazified under Tiso’s stewardship.

“It vies with Germany in the size of its concentration camps, in its oppression of minorities, and in its savage treatment of political opponents. Tiso has proved a willing Nazi tool, not only domestically, but also in his foreign policies.”

Tiso received the Iron Cross from Hitler on October 25, 1939, and was elected president of Slovakia the following day.

Dr. Tuka, although going increasingly blind as his career unfolded, had been named by President Tiso as Minister without Portfolio on March 15, 1939, and was next elevated by his patron to prime minister on October 27, when Dr. Tiso met with Hitler outside Salzburg, Austria. Tuka then replaced Durcansky as foreign minister in July 1940. On November 15, 1941, Dr. Tuka ordered Slovakia’s adherence to the Anti-Comintern Pact, and the next year he expelled his country’s Jews. Ultimately, Tuka clashed with the more clerical Tiso, displaying his own Nazi tendencies and personal desire to replace Tiso as supreme leader of Slovakia.

One biographical account called Dr. Tuka “avaricious and servile, a self-willed, ambitious adventurist.” Forced from office as party chairman by Father Tiso on January 12, 1943, Dr. Tuka also resigned as prime minister, ostensibly for health reasons, on September 5, 1944, then retired to an Austrian spa until the end of the war.

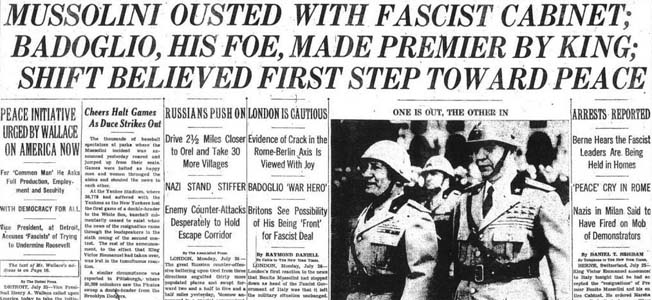

To emphasize the closeness of the Nazi and Slovak regimes, Dr. Tiso coined the term “Hitler-Hlinka jedna linka” (Hitler and Hlinka on the same track) and, indeed, they were. The new Slovak state took part in the Nazi campaigns against Poland and the Soviet Union. She was Germany’s sole ally until Fascist Italy’s declaration of war against the Allies on June 10, 1940, declared war herself on the USSR on June 22, 1941, and then on the United States and Great Britain on December 12, 1941. Because it ceased to exist as a state after the war, Slovakia never signed peace treaties with the victorious Allies.

After Pearl Harbor, Hitler’s war and the alliance with Nazi Germany became unpopular in Slovakia because many people there had relatives in the United States. A resistance movement surfaced, and the Slovak National Rising occurred on August 29, 1944. The German Army invaded and crushed the revolt within two months.

On May 5, 1945, Dr. Tiso and his entire government fled to Austria. He found sanctuary at the Capuchin monastery at Altotting in Bavaria but was captured there by U.S. Army Intelligence agents on June 8 and deported to Bratislava, where he was tried and convicted as a war criminal.

Father Tiso spent the night before his execution in prayer with a Capuchin priest, his appeal to Czech President Edvard Benes for clemency having been denied. According to the New York Times edition of April 18, 1947, “Msgr. Josef Tiso walked firmly to the scaffold where he was hanged in the Bratislava jail.”

Dr. Tuka had been arrested and tried the previous summer. He was convicted of crimes against humanity by a Slovak national tribunal. Two dates have been given for his execution by hanging at Bratislava, either August 20 or 28, 1946.

Karol Sidor survived the war and fled to Canada, while several other lesser Slovak Fascists also escaped both Allied and domestic postwar justice, but that is not the end of the story. The democratic Czech republic based in Prague was overthrown a second time, by domestic Communists in 1948, and this Red regime lasted for 41 years until it, too, was deposed by a popular uprising in 1989.

The “Velvet Revolution’s” first president was famous Czech author and playwright Vaclev Havel, who left office on February 2, 2003. And what of Slovakia? On Valentine’s Day 2003, it announced “plans to deploy a radiation, chemical, and biological protection unit to the [Persian] Gulf,” according to the Baltimore Sun. On May 18, 2003, Slovakia voted to join the European Union as a sovereign republic once more.

Towson, Maryland, author Blaine Taylor has written 12 books on the Axis powers in World War II. Among these is Mrs. Adolf Hitler: The Eva Braun Photograph Albums, 1912-45.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments