By David Alan Johnson

The bombers seemed to arrive overhead with much less warning than on any past air raid. Olive Bayliss, who lived with her family over at London Wall, in London’s City District, was certain that the Luftwaffe came in faster than usual tonight, catching everyone by surprise.

Olive’s father, an air raid warden, lost no time in evacuating everyone from the flat when the first fire bombs clattered on the roof, which was the first indication that there was an air raid that night, December 29, 1940. Before going down to the air raid shelter, Mr. Bayliss climbed up on the roof to extinguish the fire bombs that had landed.

At Fighter Command Headquarters in Stanmore, Middlesex, the incoming raid was no surprise––the staff of the headquarters’ Filter Room had been tracking the enemy bombers for about an hour.

At about 5:15 pm, one of the blue-uniformed WAAFs on duty received a telephone call from Ventnor radar station on the Isle of Wight: “Hello, Stanmore,” the voice of another WAAF coolly reported, “I have a plot of five-plus hostiles.” Five plus soon became 10 plus and, as the German bombers came into range one by one, finally reached a total of 20.

The 20 incoming bombers were the Heinkel He-111s of Kampfgruppe 100, which had taken off from the Luftwaffe airfield at Vannes, Brittany, at 5:30 pm (4:30 pm

London time).

Kampfgruppe 100 was an elite pathfinder wing, staffed entirely by handpicked pilots and aircrew. Their job was to drop thousands of fire bombs on the assigned target at the beginning of an air raid, creating a prominent bull’s eye for the rest of the bomber fleet.

Nicknamed “the Fire Raisers,” Kampfgruppe 100 was well known for having the best pilots and crews in the Luftwaffe. The unit’s commander, veteran pilot Hauptmann Friedrich Ashenbrenner, had flown numerous bombing missions over England since September 1940, when the Blitz against London began.

KG 100’s special He-111 H2s were equipped with a device known as the “X-apparatus,” which allowed the navigator to find his target on even the darkest or foggiest of nights. It was an invaluable, although not altogether foolproof, aid to navigation.

The X-apparatus picked up a radio beam that was transmitted by a Luftwaffe Signal Corps station on the Normandy coast. This beam, the “primary beam,” was aimed so that it would pass directly over the assigned target. The He-111 would simply fly along the primary beam all the way to the target.

This primary beam was intersected by two secondary beams that crossed the “X.” When Aschenbrenner’s bomber crossed the first intersecting beam, the “advance signal,” this indicated that he was about 10 miles from the target. Crossing the second beam, the “main signal,” prompted the bomb aimer to toggle his load of incendiary bombs.

The first time that Hauptmann Aschenbrenner and KG 100 had used the X-apparatus had been against Coventry on the night of November 14. That night’s raid had been one of the most destructive attacks in the Blitz against Britain. Following the Coventry raid, the German Propaganda Ministry coined the word “Coventrized,” meaning “burned to the ground” or “obliterated.”

On this Sunday afternoon, Aschenbrenner received orders that tonight’s objective would be London. Once again, he and his Gruppe would spearhead the attack. KG 100’s He-111s would go in low and fast to light up the target area with incendiaries.

The objective within “Loge,” the code word for London, would be the City of London. The City District, with its hodgepodge of old buildings, packed with textiles, books, and other highly flammable goods, was tailor made for Aschenbrenner’s “Fire Raisers.” Old-time London firemen called these buildings “torches looking for a light.”

At St. Paul’s Cathedral, about a mile from Olive Bayliss’s flat, one of the men on roof patrol telephoned the cathedral’s control center at 6:05 pm to report that air-raid sirens were sounding out to the southwest.

George Garwood, a member of the Cathedral watch, received the call and told the patrol that he would be right up. But before Garwood could put on his ax belt and helmet, the roof patrolman telephoned again—he could see incendiary bombs falling just across the river in Southwark. By the time Garwood reached the roof, the local sirens were sounding, and fire bombs were dropping on the cathedral itself.

Hauptmann Aschenbrenner had missed his target, the City of London, by about 1,000 yards. This was actually good bombing, considering the fact that he could not even see the ground because of the ten-tenths cloud cover. The other 19 Heinkels came in right behind him. Every one of them put their incendiaries right on target, which was the immediate vicinity of St. Paul’s.

Not every bomb posed a threat. Some failed to ignite, hitting the pavement with a loud, metallic crack. Five bombs landed on the newspaper offices of Bouverie House on Fleet Street. Of the five, one did not explode, one burned itself out on the concrete roof, and the other three were extinguished by the night watchman.

The incendiary bomb—frequently abbreviated as “IB”—was small, cheap to manufacture, and very effective. It measured about a foot in length, about three inches in diameter, and weighed one kilogram (2.2 pounds).

When an IB landed on a roof or struck the pavement, its magnesium core burst into life, throwing white-hot splinters in a diameter of about 10 feet. It stopped sputtering after about a minute and began glowing intently at about 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit for about 10 minutes. During the first minute, a sandbag or a shovel full of earth would very quickly snuff it out.

Although the IB was not the most sophisticated of weapons—a London Fire Brigade officer called it “not a very clever bomb”—its small size was its greatest advantage. The bombs were packed into cylindrical containers called “Molotov Breadbaskets,” with 36 bombs in each container. Each of KG 100’s He-111s carried five of these containers, which totaled 180 fire bombs. After being released, each breadbasket burst open at a preset altitude, spilling its contents over a confined area.

On the previous Sunday, December 22, the Luftwaffe introduced a new tactic: the fire blitz. The Luftwaffe set out to destroy the city of Manchester by dropping only incendiaries, thousands of them, and had largely succeeded. Whole sections of the city were burned out, reduced to street upon street of smoldering buildings by daybreak.

Because the Manchester fire raid had been so successful, Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle, commander of Luftflotte 3 (Air Fleet Three), suggested that a full-scale incendiary raid be directed against London. Sperrle’s suggestion was approved by Adolf Hitler, and the raid was planned and put in motion from Sperrle’s headquarters in the Hotel Luxembourg in Paris.

With a bit of luck and the help of a slight northeasterly wind, the crews of KG 100 managed to start several fires within a short time. None of the crews knew exactly where their bombs were going any more than Hauptmann Aschenbrenner did because of the dense cloud cover. They just unloaded their bombs where the X-beams crossed.

The fire bombs of KG 100 did their job with frightening efficiency, punching or burning their way through roofs to start hundreds of fires. Several thousand feet above the clouds that covered London, Aschenbrenner could see the glow of the fires through the overcast. His men had done their job, creating a target, an aiming point for the rest of the Luftwaffe’s bombers.

As Aschenbrenner and the rest of KG 100 turned for home, the bombers of Sperrle’s Luftflotte 3 arrived over the target. These aircrews could also see the reddish patch in the clouds and dropped their bombloads on this vivid aiming point. With each new load of incendiaries, punctuated by the occasional 550-pound high-explosive bomb, the fires within the City grew both in size and intensity.

By 7 pm, 55 minutes after KG 100 arrived over the City, three separate fire zones had broken out. The largest, nearly three-quarters of a mile long and a quarter-mile wide, surrounded St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Although the City District is well known for its old churches and other quaint old places, it also had more than its share of military targets—all rated top priority by the Luftwaffe. The Wood Street Telephone Exchange and the London Telephone Service, with their vitally important overseas communications lines, along with the General Post Office telephone and telegraph services, were important enough to rate pinpoint attacks as separate targets. The district’s six rail stations had also been earmarked as critical, along with all the bridges crossing the River Thames.

The Central Telephone Exchange was one of the first of these essential targets to be destroyed. From the roof of St. Paul’s Cathedral, George Garwood watched as it burned down “without a bucket of water to put on it.”

Lack of water was a major problem for the London Fire Brigade (LFB) that night. All of Western Europe was experiencing abnormally low tides on the night of December 29, including the Thames River Valley. Because of these unusually low tides, the Thames was reduced to a small, narrow stream, making it just about useless to the LFB as a source of water.

To make matters even worse, one of the few high-explosive bombs dropped so far had cracked the City’s primary water main somewhere along its two-mile length. So many fire appliances—the Fire Brigade’s term for fire engines—were linked up to the existing mains that water pressure dropped to zero. With the City main fractured, the smaller mains tapped dry, and the Thames all but dried up by the low tide, the expanding fire zone within the City was cut off from its water resources.

Everything, every street and every building to the north and northeast of St. Paul’s Cathedral, would burn in one vast fire—one fireman called it the “biggest funeral pyre in the world”—until the area finally burned itself out. Once in a while, the wall of a fire-weakened building would flame up suddenly before crashing down into the street with a deafening roar.

An estimated 24,000 incendiaries, plus high-explosive bombs, fell on London during the attack.

Paternoster Square, the home of London’s publishing industry with over five million books in its warehouses, was going up in a brilliant, colossal bonfire. Only St. Paul’s itself was not on fire, but it looked like it would be only a matter of time before architect Christopher Wren’s venerable old structure (opened in 1708) would be burning along with its neighbors.

The fire-watching crew at the Daily Telegraph building on Fleet Street had a full view of St. Paul’s from the west and reported that a steady hail of bombs had bounced off the Cathedral’s huge dome during the first half hour of the raid.

Thus far, the Cathedral Watch had managed to deal with every incendiary before it could do any damage, but the crew could not reach every bomb as soon as it fell. At 6:39, the Control Centre received a telephone call from Cannon Street Fire Station. The firehouse switchboard reported that the dome of St. Paul’s was on fire.

At the cathedral, the fire watch discovered that an incendiary had punched halfway through the dome’s outer lead covering. The bomb was going to be a bit awkward to get at in spite of the fact that its tail fins were jutting through the outside of the dome, but it did not seem to pose anything resembling a serious threat.

From the street, however, it looked as though the dome was burning. The brilliant white light of the sputtering bomb gave the impression that a major fire had taken hold. It was nothing but an illusion, but it was a convincing illusion.

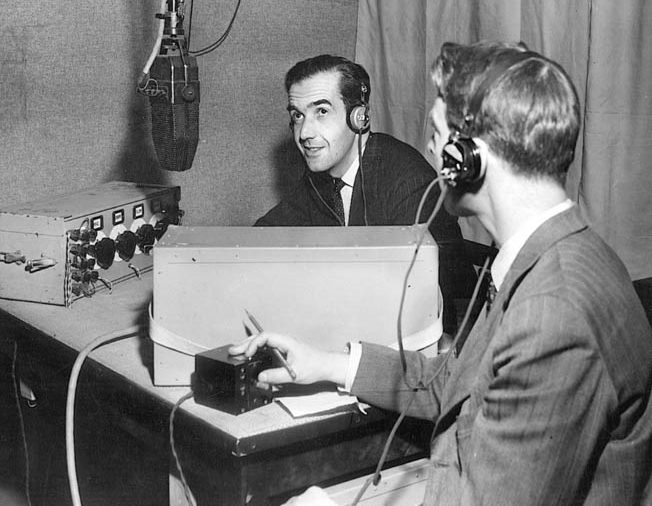

In a nearby street, American radio correspondent Edward R. Murrow of the Columbia Broadcasting System had already given up all hope that the cathedral could be saved. “Tonight, the bomber planes of the German Third Reich hit London where it hurts the most—in the heart.” Murrow was making his nightly report to New York.

“And the church that meant most to Londoners is gone. St. Paul’s Cathedral, built by Sir Christopher Wren, her great dome towering over the capital of the Empire, is burning to the ground as I talk to you now.”

While Murrow was making his broadcast, members of the Cathedral Watch were slowly making their way toward the bomb. When it stopped sputtering and began glowing at 4,000 degrees, its molten core melted the dome’s lead skin that held it in place.

Before anyone could get near it, the bomb fell outward, slid down the outside of the dome, and landed in the Stone Gallery, the walkway that circles the bottom of the dome, where it was easily disposed of. At the time, this was referred to as the “Miracle of St. Paul’s.” Cynics have insisted that it was only gravity.

No one in the fire zone was given any time to catch their breath. Not many fire spotters were on duty on this Sunday night, but the few who were on hand were busy. New clusters of bombs kept falling, landing with their dazzling white sparklers. The fire crews put them out by dropping sand bags on them, just as the St. Paul’s watch had done.

The firewatchers at the Guildhall, which might be described as the City’s town hall, had done a successful job of saving their building from serious damage. The 15th-century building was surrounded by collapsing, fire-ruined buildings but was still untouched by flames itself.

Firewatcher R.C.M. Fitzhugh gave this impression of the view from the Guildhall roof: “The block bounded by Bassishaw House, Fore Street, Aldermanbury, and Basinghall Street appeared to be one solid mass of flame,” he wrote in his diary. “St. Stephen’s, Coleman Street, was soon enveloped in flames, and we could see the steeple and weather cock fall. Fires were everywhere in the City area.

“From time to time, heavy high-explosive bombs or land mines were dropped…. There would be the sound of something rushing through the air, then a brilliant flash would light up the entire sky and horizon and followed within two or three seconds by the most resounding explosion.”

The Guildhall roof spotters knew more about the state of the City’s fires than the commander of Luftflotte 3. In his suite at the Hotel Luxembourg in Paris, Feldmarschall Sperrle did not have an accurate idea of the damage that was being done by his bombers. He had been receiving reports that the target was coming under constant attack and that it had been set brilliantly on fire by KG 100. But because of the cloud cover over London, these visual reports from his bomber crews were not precise.

Even so, Sperrle had every reason to be optimistic. He was planning a second attack, another wave of bombers that would drop high explosives on the target area, which would finish off anything left standing. Sperrle was as concerned with the weather report as he was the bombing results. The heavy overcast that covered southern England was threatening to turn into a rain storm, which might well force him to cancel the second attack.

For Luftflotte 3’s bomber crews, the night’s attack was turning out to be much easier than anyone expected. The target area, all lit up and visible from the Channel coast, would have been difficult not to hit.

Antiaircraft fire was sporadic—once in a while, some antiaircraft shells would pop through the overcast and burst a safe distance away—and were usually not accurate. The German air crews kept their eyes open for the RAF’s night fighters, but there had not been any sign of them so far.

It was satisfying to know that all their bombs were landing on target. On some raids nobody could be absolutely certain if they were bombing their objective or some vacant field miles away, but not tonight. The only real problem, and this was minor, was with the turbulence from the fires. Flying over the rising hot air lifted the bombers upward for several hundred feet, but this did not interfere with bombing accuracy.

And the bombing continued to be extremely accurate. Besides vital communications links like the Central Telephone Exchange and the General Post Office, Sperrle’s transportation objectives were also being hit hard. No trains were running within several miles of Central London. Cannon Street rail station and London Bridge Station were both on fire, along with Waterloo Station, which was actually out of the fire zone, and Fenchurch Street Station was shut down because of damaged signals and blocked tracks.

Guildhall’s communication center received a priority telephone message from Prime Minister Winston Churchill sometime before 7 pm—St. Paul’s must be saved at all costs. Churchill’s communiqué was passed directly to the control center at St. Paul’s, but it had little effect. Although Churchill’s message was both welcome and appreciated, there was not much else for the Cathedral Watch to do that had not already been done.

Civilian fire spotters frequently spelled the difference between survival and disaster, not only at St. Paul’s and Guildhall but at office blocks and buildings throughout the City. But sometimes even the best intentions and efforts of the fire-watching crews were not quite enough. The fire-watching team at a Building Society on Ludgate Hill, just a short walk from St. Paul’s Cathedral, managed to put out every fire bomb that landed on their roof.

But the building’s waterproof paper window panes, which replaced the glass panes that had been blown out in an earlier air raid, had been set on fire by flames from the building next door. Burning embers managed to find their way through these vacant windows, where they started small fires inside the Building Society’s offices. It did not take long before an entire section of the building was burning. The fire was obviously more than two volunteer fire crews could deal with, so the men sent for the Fire Brigade.

When the fire engines stopped in front of the Building Society, the firemen stepped off the machines to take a good look at the fire. They stood in the street for a minute or so, gazing up with clinical detachment. Finally, one of the firemen spoke up: “It’s not nearly big enough yet,” he said. “We’ll be back later.”

With that, the entire crew climbed back aboard their fire engine and drove off, giving the Building Society’s fire watchers their last glimpse of the London Fire Brigade for the rest of the night.

Some people tried to carry on with their everyday routine in spite of the air raid, which sometimes brought them closer to disaster than they realized. At 7:30, a milk-tank driver left Hounslow, Middlesex, for his nightly run through London to Bow, East London, which would take him right through the City. When he reached the vicinity of Blackfriars Bridge, about a quarter-mile southwest of St. Paul’s, just about everything in front of him was a solid wall of fire.

He always drove this route, straight along Queen Victoria Street, and could see that the street was lined with burning buildings. But the driver was not about to let anything as trivial as an air raid change his usual route. He put his rig in gear and headed eastward, right up Queen Victoria Street.

He had not gone far when a policeman stopped him and asked him exactly where he thought he was going. The driver matter-of-factly answered, “Bow”––to East London directly through the fire zone.

“Not through here, you’re not,” the policeman declared and pointed in the direction of Mansion House, the Lord Mayor’s official residence. “Look at that!”

The driver looked and saw the façade of a fire-weakened building crash down into the street. If the policeman had not stopped him, the milk-tank driver estimated that he would have been passing that building when it collapsed.

One of the leading topics of conversation throughout London was the possibility of a follow-up raid by the Luftwaffe. Everyone remembered the first air raid on London, which took place on September 7/8, 1940, when bombers returned to drop high explosives on the fires that had been started earlier. It seemed more than a good possibility that the same thing would happen tonight; the City’s fires certainly offered a tempting enough target.

Feldmarschall Sperrle still had his second wave scheduled, even though he was receiving nothing but bad weather reports from his bomber bases. Every one of Luftflotte 3’s airfields reported deteriorating weather conditions—it was also raining in Paris—and staff meteorologists were predicting that the rain would continue for at least another 24 hours.

But reports of the attack on London were positive and encouraging—just about every dispatch mentioned vivid fires burning in the target area—and Sperrle was unwilling to cancel the second attack. His second wave of bombers, carrying loads of high explosives instead of incendiaries, would be able to inflict maximum damage on the target area.

Because of the weather, Sperrle decided that it might be a good idea to postpone the second strike for a few hours. A short rollback might give the weather a chance to improve, in spite of what the weather experts were predicting, and would still allow his bomber units to drop their bombs under cover of darkness. Luftflotte 3 would still have its unmissable aiming point along with better weather if all went well. The order went out to all airfields: stand down until further instructions.

More than 1,400 fires were burning in and around the City. All over London people were stopping whatever they were doing and going outside for a better look. A woman who lived in Chelsea, several miles west of the fire zone, went up on her roof to check on the fires. She could clearly see the dome of St. Paul’s silhouetted against the glare. The sky was incandescent with red and orange that seemed to tower miles in the air. She was certain that this was the last she would ever see of St. Paul’s.

By this time Guildhall had finally succumbed to the surrounding fires. Blazing bits of ash from the church of St. Lawrence Jewry, which was only a few feet away and had been burning for well over an hour, had started fires in the hall’s wooden roofing beams. High winds fanned the flames, blowing them into other parts of the Guildhall complex. The Fire Brigade came, but there was not much it could do. One of the fireman told RCM Fitzhugh that his men had been ready for the past 15 minutes but there was no water.

By 9:50, the fires were out of control. The noise from the wind-driven flames and the crackle of burning beams and roof timbers was loud enough to drown out the shouting of the firemen who were standing in the street with dry firehoses. Telephone operators in the control center stayed on the job even though the exchange lines were dying one at a time.

Guildhall’s logbook gives a cryptic account of the City’s ordeal on this night. Each entry gives the time and nature of each incident. (“IB – F” signifies “Incendiary Bomb – Fire.”)

Call:No. 16.20Knightrider Street – Queen Victoria StreetIB – F

No. 596.45Eastcheap by Mark Lane. “Explosive IBs IB – F

are bursting all over the place.”

No. 626.59Queen Victoria Street by Mark LaneIB – F

“Well alight.”

No. 74b8.10YMCA Building, 186 Aldersgate St. IB – F

“Fire spreading rapidly – Nobody in Building.”

No. 1379.1026/27 Bush Lane – “LFB wanted urgently.”IB – F

No. 17110.0012/16 Red Lion Court “LFS in attendance, IB – F

but no water.”

The telephone operators received reports of only a fraction of the more than 1,400 fires in and around the City. This was partly because Guildhall’s telephones were swamped by incoming calls, but mostly because there were so few people in the City on this Sunday night. There was no one on hand to report the outbreaks.

By 11:30, it was obvious that Guildhall would have to be evacuated. By this time there was only one telephone line still in operation. The officer in charge told the operators to leave the building since there was nothing else for them to do.

While Guildhall’s telephone operators were leaving the building, the tide began to come in. Water was now being relayed from the Thames, via 31/2-inch fire hoses into the 5,000-gallon dams that had been installed throughout the district. It was only a trickle, but a critical trickle. A few hours earlier and it might have made all the difference.

Firefighting units were also arriving in the City fire zone from all over the greater London area as well as throughout the Home Counties. They were too late to do anything about the fire damage that had already occurred, but at least they would have some water to help keep the fires from spreading.

A total of 183 bomb incidents had been logged by Guildhall’s telephone operators beginning at 6:20—29 of these had been high-explosive bombs. The operators kept taking reports right through the air raid until around midnight.

Shortly before the evacuation order was issued, a call came through to report that Number 5 Creed Lane had been hit by an incendiary. This was no different from any of the other calls that had jammed the exchange lines during the past 51/2 hours, except that this was the last one for the night. The time was 11:40.

At Fighter Command Headquarters in Stanmore, Middlesex, the ritual of plotting and tracking the enemy bombers also continued throughout the night. The atmosphere inside the Operations Room remained quiet and tense as the WAAFs mechanically repeated the height and range of the bombers on the huge table map. For the past hour or so they had been moving steadily southward, away from London.

From their overhead gallery, the Operations staff watched as the red arrows retreated toward the south––across Surrey and Kent and Sussex to the Channel. As the bombers crossed the Channel and made their way back to their bases in France, the arrows were removed from the map, one by one, until the map was clear of all enemy aircraft. The Luftwaffe might be back later, but for the first time since 6 pm the dark area on the map that represented London was free of the red markers.

No one in London had any idea that the air raid was over, not even anyone within the City fire zone. The antiaircraft guns had gone silent, but that was no indication of anything––there had been lulls in the shooting throughout the attack.

The firemen and roof spotters were surrounded by their own world of noise and fire. The fires themselves rolled like a thunderstorm, and more than 2,000 pumps made their own kind of thunder. Many had not been able to hear the bombers for the past few hours, so they could not possibly know that the planes were gone.

Ten minutes after the Creed Lane bomb incident had been logged, the all clear sounded. The high-pitched howl of the air raid sirens flooded the blacked-out streets all over London. The sirens even penetrated the interiors of air raid shelters throughout the area, where they produced a collective sigh of relief.

There were some who could not bring themselves to believe that it was all over. One auxiliary fireman was taken completely by surprise when he heard the sirens. “I immediately thought the authorities were sending an unprecedented second alert, in a desperate attempt to warn us of some new menace,” he said. “I frantically tried to think what it could be—we already had rattles for gas and church bells for invasion.”

When the sirens held the high note, signalling the all clear, the fireman was absolutely incredulous. “The crazy thought even crossed my mind that Fifth Columnists had somehow managed to give a false All Clear. It was simply unbelievable that the Germans would miss the juiciest target in history—and how could our people be so sure that they were not coming back?”

Some of the Guildhall volunteers decided to stay inside the building when the evacuation order was given. They went to work salvaging some of the library’s centuries-old books and documents. After they finished, most of them straggled over to the pubic air raid shelter on nearby Basinghall Street to get some much needed sleep.

A few of the volunteers went out to look for something to eat, maybe a sandwich and a cup of tea at an all-night café. While he was walking through the district, RCM Fitzhugh noticed that it was beginning to rain.

Feldmarschall Sperrle realized that he did not have any other choice. It had been raining for several hours in Paris, and the weather experts were predicting no let-up in sight. Almost every one of Luftflotte 3’s airfields had reported that they were completely shut down with unusable runways that were choked with mud. From his suite in the Hotel Luxembourg on Paris’ Left Bank, Sperrle finally canceled the second attack.

It had been a reluctant decision, and Sperrle had taken several hours to make it. The first wave had set the target well alight, and the target area was more than ripe for a second attack. But a second strike was clearly out of the question; one bomber had already crashed while trying to land at Orly Field. If Sperrle went ahead with his original plan, he knew that he would almost certainly lose many more aircraft.

There was no use brooding about it; there was nothing anybody could do about the weather. Sperrle issued the necessary instructions to his staff officers, who began relaying the stand down orders by telephone. Since there was nothing else to be accomplished, Sperrle said good night to his staff and went to bed.

The all clear did not mean much to the firemen on duty in the City. Their night would not come to an end for several more hours. Fires were still out of control but were no longer spreading as quickly as before; the linkup from the Thames was making it possible for the fire services to begin holding the flames back.

There was no let-up for most of the fireman—only hour after hour of holding a pressurized firehose in sweltering heat and stinging smoke. The sun had come up by 7 am, but because of the drizzle and the overcast sky it was hidden from view. However, the water relay from the Thames was now having its full effect, and the fire crews were finally able to do more than just watch while the City burned down around them. By 7:30, the fires had been contained.

The new day also brought another working Monday for Londoners. In a few hours, shops and offices within the City, as well as throughout London, would be opening for business—at least the businesses that were still standing.

The air raid did not stop Londoners from going to work. During the September to November air raids, when the Luftwaffe bombed London every night for 57 consecutive nights, the morning after each attack saw workers making their way around bomb damage and cratered roads to get to their jobs. This particular morning, after the great fire raid, was no different.

Londoners had learned that the morning after an air raid meant chaotic traffic and that it was best to leave for work much earlier than usual. Today, even an early start was not much help. Every road into the City, along with all four Thames bridges, was closed to automobile traffic. London Transport issued an official report on the traffic situation which began with this comically understated appraisal: “As a result of the intense attack last night, traffic conditions in the Central London area are bad.”

Traveling by train did not offer much of an improvement. All but one of the City’s rail stations was closed. The official notice that greeted passengers on this Monday morning read, “Due To Enemy Action Trains Will Be Subject To Delay.”

Most people who worked in the City rode their usual trains or buses as far as they could and walked the rest of the way. Many walked for a mile or more over rubble and leaky firehoses and arrived at their offices wet and grimy. Clerks and secretaries often arrived hours late and were congratulated for having shown up at all.

After making their way around roadblocks and through police lines, thousands arrived at work only to find that their offices or factories had disappeared during the night. Hundreds of firms had been destroyed; businesses that had taken a lifetime to build up were gone.

Displaced workers simply wandered aimlessly about, not knowing what else to do. A crowd gathered outside St. Paul’s, as though hoping that some of the cathedral’s charm might rub off on them. St. Paul’s became a symbol of London’s defiance in the Blitz.

A damaging blow had been dealt to the business heart of London, along with its essential war services—transportation and communications facilities. The Post Office Telephones on King Edward Street were a total loss; the building itself had been completely burned out, and the basement with all of its transformers was flooded. The Central Exchange on Wood Street had also been completely destroyed along with every other building on both sides of the street.

Feldmarschall Sperrle was thoroughly disappointed that he had had to call off his second strike. The rotten weather had just been bad luck. He hated to give up the opportunity to follow up his fire raid with an all-out high-explosive attack. As far as Sperrle was concerned, only half an air raid had taken place the previous night.

He had no real idea of the damage that his bombers had inflicted. Bomber crews only mentioned “sehr starke Brände”—very fierce fires—in the target area, and reconnaissance aircraft had not been able to photograph the target because London was still covered by a solid layer of cloud.

An official report gives evidence of the Luftwaffe’s lack of detailed information. “Toward the end of the attack,” the report states, “there were over 100 widely spread fires with dense, black smoke, mainly in the City and to the north.” Actually, more than 1,500 fires resulted from the incendiary bombs alone, with even more damage resulting from the strong wind.

German Propaganda Minister Dr. Josef Goebbels shared Sperrle’s opinion. If Goebbels had known about the chaos caused by the raid, he would have issued one of his usual long-winded descriptions of the attack. Instead, only a routine communiqué was issued on December 30: “Strong bomber forces attacked London again last night.”

Within the next few days, German intelligence would learn all about the full effect of the fire raid, and the Propaganda Ministry would jump into full gear. Among other things, Goebbels’ department would claim that 100,000 incendiaries were dropped. Actually, about 24,000 were dropped.

But for now, the propagandists did not even bother with the usual practice of interviewing bomber crews. Because the second strike had been canceled, the raid was not considered important enough.

The center of the City’s fire damage was in the area to the north and northeast of St. Paul’s. Almost every building within this district had been destroyed, with row upon row of free-standing walls and fire-blackened ruins creaking in the wind. Hundreds of foot-long IBs had burned themselves out on the pavement, leaving indelible marks on the concrete. These splotches reminded New York Times reporter Raymond Daniell of chewing gum on a New York City sidewalk.

One of the few buildings to survive the fire storm was—the height of irony—Redcross Street Fire Station. The firehouse was certainly charred from the surrounding buildings, but it remained in service. After the Royal Engineers pulled down the nearby fire-weakened buildings, the firemen and firewomen would plant a thriving vegetable and flower garden, which included apple trees.

By mid-morning, the fire services were being sent home in increasing numbers. Some had been tending fires for more than 14 hours without even a chance to sit down. One at a time, the trailer pumps, turntable ladders, and heavy units, all manned by bone-weary and indescribably filthy firemen, left the fire zone and headed for their home stations.

Sometimes there was a small surprise to hurry the departing firemen on their way. At Tower Pier, just adjacent to the Tower of London and about a half mile from St. Paul’s, Fireman L.P. Andrews and his crew had been pumping water from their fireboat into the fire zone since the small hours. Sometime during the late morning, the fireboat was approached by a naval launch. An officer on board the launch hailed the firemen: “What are you doing there?”

“Pumping water,” Andrews shouted back.

“What time did you arrive?” the launch persisted.

“About 2:30.”

“Was there anyone here when you arrived?”

“No.”

“Well, you better get the hell out of it. I evacuated this area at about 1:30. You are probably about 20 feet off a parachute bomb.”

A parachute bomb, also known as a land mine, was a cylinder containing about 1,500 pounds of high explosives. It came down by parachute and was capable of doing an enormous amount of damage. An exploding land mine could wipe out an entire row of houses or level the better part of a city block and still have enough punch to shatter windows two or three streets away.

The fireboat’s crew immediately stopped the pumps, disconnected the hoses, let go the ropes, and let the current take them well clear of the area before starting their engines for their trip back to their base at Tilbury, Essex.

Nobody in London or anywhere else was able to find out much about the air raid from official news sources. Wartime censorship and security stopped the release of any specific facts or of any useful information at all.

A bus driver from the Paddington section of London made this note in his diary: “I cannot find out much about last night’s fire … the 6 pm news tells us [only of] the wilful firing of the City of London and severe damage.”

The newspapers did not give out much information either. Monday’s “Late London” edition of The Times featured this two-column headline on page four:

FIRE BOMBS RAINED ON LONDON: MANY BUILDINGS HIT

The story beneath was as dim as the headline. Strict wartime censorship prevented editors from printing a more extensive report. It was better to run a vague, noninformative story than to be charged with supplying “information of value to the enemy.”

Most of the regulars and auxiliaries of the London Fire Brigade returned to their usual sweep-and-polish routine almost as soon as they arrived back at their stations.

Redcross Street Fire Station, which had been abandoned at the height of the fires, was soon back in operation. When Fireman James Goldsmith returned to the station, he began cleaning and sorting his gear just in case of another call. Equipment and lengths of hose would sometimes be lost during a fire, which usually presented a problem. But today there was plenty of gear lying about right on the street.

Nearby Whitecross Street was littered with several burned-out and abandoned trailer pumps complete with all their tools and equipment. The hardware only had to be picked up and carried off.

The great fire raid was over, but the Blitz against London would not end for another 41/2 months. Feldmarschall Sperrle’s bombers would attack London again between mid-January and mid-March 1941, but these were mainly small nuisance raids.

The big raids began again in March 1941 and continued throughout April on the basis of roughly one raid per week. Two major raids would take place in April, which would be remembered by Londoners as “The Wednesday” and “The Saturday,” April 16 and 19, both of which were triggered in retaliation for an RAF raid on Berlin.

The last Blitz raid before Hitler invaded Russia in June would come on the night of May 10/11, 1941. To many Londoners, this was the worst of all. For 61/2 hours Sperrle’s bombers dumped their incendiaries and high explosives on London. When the attack finally ended, rail and transportation centers had been seriously disrupted, and thousands of houses and factories were destroyed.

Westminster Abbey, the Tower of London, the British Museum, and many other famous landmarks had been bombed but had not been destroyed. More than 1,400 Londoners had been killed, and another 1,800 were wounded.

Germany would not be immune to bombing as the war went on. Just as London had suffered as severely as Warsaw and Rotterdam earlier in the war, cities within the greater German Reich would feel the brunt of bigger and better armed Allied bombers. One thousand bombers would attack Cologne on the night of May 30, 1942. Throughout the war just about every major city in Germany—Dresden, Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Leipzig, and Berlin—would be bombed relentlessly by the RAF at night and the U.S. Eighth Air Force by day.

The same fireman who had been alarmed when the sirens sounded an early all clear on the night of December 29 was stationed in Germany after the war. He had a firsthand look at the terrible destruction that had been inflicted and was moved to comment, “Christ, we never knew what bombing was.”

My aunt was a teenager in London during the war and a volunteer plane spotter. She said that the large Jewish population of the East End were convinced that the intensive bombing of the area was not solely due to its proximity to the docks (This was not completely unfounded – for example documents found after the war show that planned German transAtlantic attacks on New York were to be centered on Delancey St. in the then very Jewish Lower East Side.). She used to talk about the “spirit of the Blitz” and how it brought Londoners of all social classes and regional or ethnic backgrounds together, and was a source of morale and conviction that they would win the war in the end.

Her mother was a seamstress in a shop making uniforms. The ladies in the shop received their milk ration at work, and one day just after delivery the woman across from her said “This war is all the fault of you Jews.” My grandaunt, who had a son in combat in the British 8th Army in North Africa, replied “You’re a terrible person” and broke her bottle of milk across that woman’s head, to general approval. The milkman was moved to give her his personal milk ration.

One factor that inhibited the German effort from greater success was they had what was essentially a tactical air force more suited to field combat situations. They did not have a heavy bomber fleet like the British or the Americans. Also, the war was begun before even the General Staff planned on full readiness.

The German incendiary had a core of thermite, a mix of iron oxide and aluminum powder. It weighed about 1 kilogram (2.2 lbs) When ignited it burned for about a minute at 4000 f igniting the jacket of magnesium aluminum alloy called Elecktron metal burning for about 10 minutes. Throwing water on a burning incendiary resulted in an explosion hurling chucks of burning magnesium. Usually to extinguish a burning incendiary one would cover it with sand or scoop it up with a shovel and drop in a bucket of sand. Stirrup pumps, a device which looked like a bicycle pump were place in a bucket of water. Stroking the handle would project a stream of water up to 25 feet allowing the user to extinguish fires started by the incendiarues.