By Mark N. Lardas

In 1863 the tide was running against the South—except in Texas. A new Confederate commander, John Magruder, chased the Yankees out of both Galveston and the Rio Grande Valley. Holding on to Texas challenged Magruder, however. Despite a brief incursion by the CSS Alabama in January, the Union Navy was dominant in Gulf of Mexico waters, allowing the Federals to strike anywhere along Texas’s 400-mile coast.

Much of this coast was tidal flat and swamp. Texas had few railroads. Supplies followed rivers. An invasion of Texas had to come through Shreveport, La., or six ports on the coast. But Magruder had to cover all these invasion points—and the eastern border of Texas—with only 2,500 men. A Union operation on the Red River and Union incursions at Galveston and Brownsville absorbed most of his forces.

Kellersberg Builds Fort Griffin

One exposed spot was Sabine Pass. The outlet for the Sabine and Neches Rivers, it guarded the eastern approaches to Texas. Union forces raided Sabine Pass in September 1862. Navy gunboats smashed the fort, then landed troops that burned sawmills and railroad shops, destroyed track, and pulled down the bridge over the Sabine.

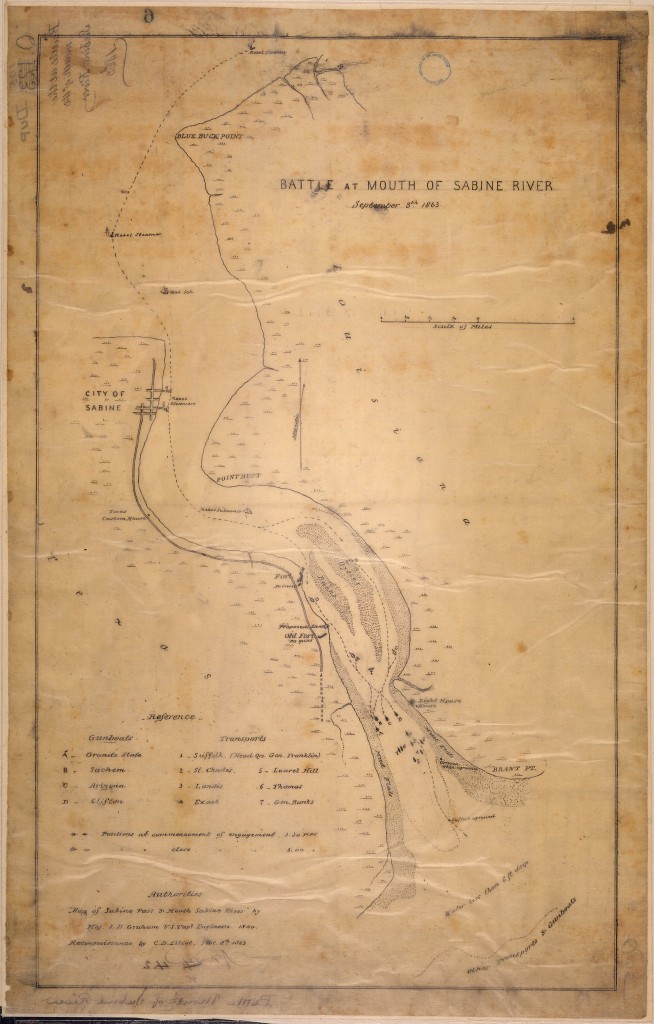

So, in the spring of 1863, Magruder sent his chief engineer for East Texas, Major Julius Kellersberg, to Sabine City with 500 slaves and orders to build a new fort. Kellersberg picked a spot upstream of the ruined fort overlooking the trickiest part of the pass—a sharp bend where two narrow channels merged. Kellersberg dug a three-sided earth embankment reinforced with iron rails and cross-ties. The fort was named Fort Griffin, after the local district commander.

Kellersberg scraped up six cannon. He took two 24-pound iron long guns and two 32-pound howitzers from forts upstream of Sabine Pass. He unearthed two 32-pound long guns that had been smashed and buried when the old fort was abandoned a year previous. They had been spiked and cut from their trunnions but were otherwise intact. He had them refitted in Galveston.

Magruder Assigns Forces to Fort Griffin

Magruder assigned the Davis Guards, a company of the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery Regiment, to Fort Griffin. Forty-two strong, this Houston militia unit raised in 1860 was composed of Irish immigrants. Their officers were Irish-American merchants and tradesmen. The ranks were filled with longshoremen and day laborers.

The Davis Guards had a reputation for mutinous and fractious behavior. Much of their negative reputation seems to have rested on prejudice against the Irish common in the 1860s. The unit had been ordered disbanded, and then the order was countermanded. Magruder’s experience with the Davis Guard was positive—it had led the charge that sealed Magruder’s victory at Galveston.

The Davis Guards had a reputation for mutinous and fractious behavior. Much of their negative reputation seems to have rested on prejudice against the Irish common in the 1860s. The unit had been ordered disbanded, and then the order was countermanded. Magruder’s experience with the Davis Guard was positive—it had led the charge that sealed Magruder’s victory at Galveston.

Whether the reassignment represented a reward, or an attempt to remove the brawling Irishmen from Galveston, or because Irish troops were viewed as most suitable for a task that required digging (Irishmen were known as canal builders), the choice was fortuitous. The men welcomed an excuse to fire cannon, conducting live-fire target practice weekly. Kellersberg assisted these efforts by planting range stakes at 300-yard intervals across both channels covered by the battery. By September the Irish-bred soldiers could use their guns with deadly efficiency.

Magruder assigned two bay steamers armed with 12-pound guns and cotton-bale armor to Sabine Pass. These “cottonclads,” the Uncle Ben and Josiah Bell, formed the Second Squadron of Magruder’s navy, a collection of river and bay steamboats armed with a miscellany of guns and protected with bales of cotton. Two unarmed transports rounded out the Confederate forces at Sabine Pass.

Banks Plans the Union Invasion at Sabine Pass

In 1863, the French were making foreign intrigue in Mexico. President Lincoln wanted Texas back under Union control before Texas and the French made common cause. He pressed Nathaniel P. Banks, commanding the Department of the Gulf, to move Union forces into Texas—preferably near the Rio Grande, where they could monitor the French. Henry Halleck, Lincoln’s chief of staff, preferred a push up the Red River.

Banks distrusted the concept of sending an army by sea 600 miles from his New Orleans headquarters, as an invasion near the Rio Grande would have required. Nor did fighting in Louisiana swampland hold appeal for him were he to sally up the Red. Instead, he decided to move against Sabine Pass. It was closer than Brownsville and 40,000 bales of Rebel cotton were within reach of the Sabine River. No doubt he was aware of his own benefit were the venture to succeed—as department commander, Banks profited from any prize money collected.

Union intelligence pegged Confederate strength in the Department of Texas to be no more than 3,500 men—40 percent more than Magruder actually had. Banks wanted to use 20,000 troops in the invasion, but the Union Navy lacked transports to carry more than 5,000 to 6,000. Under protest, the army cut its plan. Four infantry brigades, six artillery batteries, and several troops of the U.S. First Texas Cavalry (known in Texas as the “First Texas Traitors”)—5,000 in all—would be loaded into 17 transports. General William Buell Franklin would command the army contingent.

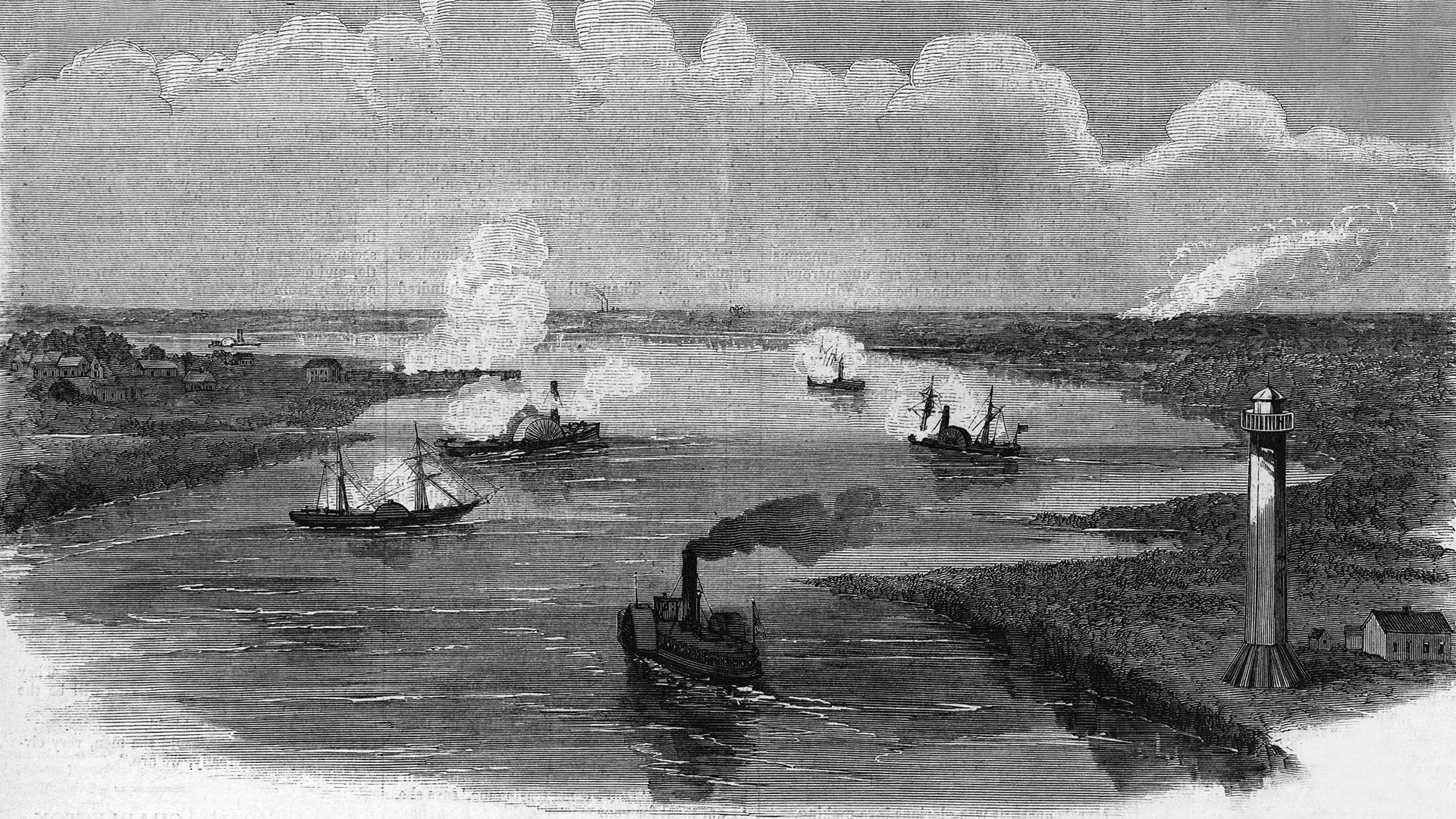

The invasion force was to be escorted by five Union warships—the deep-draft Cayuga and four light gunboats capable of entering the shallow channel. All four gunboats were acquired merchant vessels, purchased at the war’s outset or captured when attempting to run the Federal blockade. Typical of much of the Union Navy, the ships were lightly armored and carried a mixed battery of guns. They were among the few available seagoing Federal warships capable of operating in brown water.

The Arizona was a 950-ton side-wheeler, 202 feet long, carrying four 32-pound smoothbores, one 30-pound Parrott rifle, and one 12-pound Parrott rifle. She drew 10 feet. The Clifton, originally a side-wheel ferryboat, displaced 892 tons, was 210 feet long, and carried four 32-pound and two 9-inch smoothbores. She drew 13 feet. The Granite City, an iron-hulled side-wheeler, was 450 tons, 160 feet long, and drew 9 feet, 2 inches. She carried four 24-pound howitzers and a 12-pound rifle. The Sachem, screw-powered, displaced 195 tons, and drew 71/2 feet. Only 120 feet long, she carried a 20-pound Parrott rifle and four 32-pound long guns. While not the most powerful shallow-draft craft available to the Union, these ships individually were at least a match for Fort Griffin.

The Union Botches Its Landing

The Union plan called for one gunboat, the Granite City, to sail to the pass, where the Cayuga was on blockading duty. The Granite City would mark the mouth of Sabine Pass with a lantern visible to seaward.

The rest of the fleet, escorts and transports, would sail from New Orleans and rendezvous with Granite City under cover of darkness. At dawn, eight combat-loaded transports would land troops on the beach south of Sabine Pass. The four gunboats, their crews augmented with 170 army riflemen serving as snipers, would force the channel, silencing the fort with both artillery and small-arms fire. Then troops marching overland from the beaches would carry the fort. From there, the Union forces would consolidate at Sabine City, then press on to Beaumont.

The plan began unraveling when Cayuga, which had not been informed of the invasion, left station for Galveston on September 6, 1863 for badly needed engine oil. She was back on station by dawn, but by that time Granite City arrived to find the pass unguarded. Then Granite City made contact with a phantom enemy. When Granite City anchored off Sabine Pass shortly after sunset, Acting Master Charles Lamson, commanding the ship, observed a large warship steaming west along the Texas coast. It was the Union warship Ossipee, steaming to join the Federal blockade at Galveston.

Nervous about the missing Cayuga, Lamson assumed the unidentified vessel was Alabama—at that time at Capetown. He doused his lantern. Deciding Granite City was too frail to match Alabama, he raised anchor and quietly slipped east. He rode out the night in the Calcusieu River, 35 miles east, waiting until dawn before leaving its shelter.

The transports had left New Orleans in two groups on the previous day. The advance contingent, carrying the invasion forces commanded by Brig. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, departed first. Escorted by the remaining gunboats, they swept past the Calcusieu River during the night. The fleet missed the hidden Granite City, and Lamson either did not see them or ignored them. The ships also missed the mouth of the Sabine in the moonless night. Depending on dead reckoning, the fleet steamed halfway to Galveston searching for the signal lamp. At 2 am they reversed course, sailing northeast. Dawn found them off the Louisiana coast where Granite City joined them.

When the advance group finally reached the Sabine River it was daylight. They found Cayuga there with the remaining transports, waiting at anchor. Franklin decided that with surprise lost a beach landing was too dangerous. The Federal forces spent September 7 reorganizing, sorting out the confused assembly of ships, and planning how to move the invasion forward.

The Confederates Scramble to Prepare for an Attack

The Confederate forces were, indeed, no longer surprised—they were aghast. The Federal departure from New Orleans had been noticed, and garrisons along the Texas coast had been placed on full alert. For Sabine Pass, this meant sending scouts to the mouth of the pass, having the 41 gunners at Fort Griffin standing by their guns, and sending orders to recall 17 men on leave or detached service. By dawn the scouts reported the Federal ships gathering off the coast.

Captain Odlum, commanding at Sabine City in Colonel Griffin’s absence, telegraphed General Magruder with news of the invasion. Magruder had no reinforcements immediately available, and felt resistance would cause unnecessary bloodshed. Magruder ordered the fort destroyed, and instructed the garrison to retreat west.

Odlum passed Magruder’s instructions to Lieutenant Dick Dowling, commanding the fort, framing them as permission to withdraw rather than as an order to withdraw. A vote was taken. The gunners, having practiced for months, were spoiling to use their weapons. They needed little encouragement from Dowling to fight. Odlum soon received a response from Dowling: The garrison would stay and fight.

The Union’s False Start

At 6 am on September 8 Clifton crossed the bar, anchoring within three-quarters of a mile of the fort. Clifton then bombarded the fort using her 9-inch Parrott gun, firing 26 rounds of the 100-plus-pound projectiles. Two were direct hits on the fort. The rest were near misses. But they all went unanswered. Dowling had his men stand down in the fort’s bomb-proof shelters until the Union ships were closer.

Crocker examined the fort. He noted very few men in it and assumed that the lack of response indicated that the fort was incapacitated. So Crocker raised anchor at 7:30, sailing back to the main force to report that the fort had been silenced. Crocker recommended landing troops at the old fort a thousand yards south of Fort Griffin.

A new plan evolved. Four gunboats and seven transports would cross the bar. Crocker felt that all four gunboats attacking simultaneously would overwhelm the fort. With the gunboats in the lead, the flotilla would move through the two channels and land troops. By 9 am the Federal forces were on the move.

While the rest of the ships anchored out of range of the fort, Sachem steamed slowly down the Louisiana channel to cover Generals Franklin and Weitzel as they conducted a personal reconnaissance in a ship’s boat.

About that time, at 11 o’clock, the cottonclad Uncle Ben approached the fort, steaming to within a thousand yards of the boat carrying the generals. Seeing the enemy vessel, Sachem fired three rounds with her Parrott gun. Uncle Ben scurried back upriver.

Once the army leaders were satisfied, the attack began. At 3 pm Sachem and Arizona began steaming down the shallower Louisiana Channel to the east, while Clifton and Granite City entered the Texas Channel on the west. Because Arizona had the deepest draft of the four gunboats, she lagged behind Sachem as she picked through the channel. Lamson, on Granite City, did not need a reason to fall behind the Clifton. He simply did.

Fort Griffin Finally Speaks

Thus the Union ships were approaching the fort individually rather than collectively. Sachem led, opening fire at 2,000 yards. The Confederates held fire until Sachem was well within the range stakes they had laid out. When the Sachem was within 1,000 yards, at the closest approach to the fort and in the narrowest stretch of the channel, Fort Griffin finally spoke.

The unit’s practice paid dividends. The Irish Southerners struck Sachem with the fifth round they fired. More hits followed, all clustered around the pilothouse. The ship reeled under the barrage, and then, as she cleared the narrows, Sachem fell afoul of an unexpected crosscurrent that nudged her onto a shoal; the Sachem was aground. Then a shot penetrated her steam drum.

The hit effectively ended Sachem’s ability to fight, flooding her with live steam. Both the crew and a contingent of 77 sharpshooters detailed by the army were forced to flee or boil. The fortunate ones jumped overboard, and were soon floundering through waist-deep mud.

Master Amos Johnson, commanding Sachem, signaled for Arizona to tow his ship off. Arizona acknowledged the signal and indicated she would assist. As she closed, she, too, came under fire and ran aground. More fortunate than Sachem, Arizona received a respite from the fort’s fire as Clifton drew the fort’s fire away from both Sachem and Arizona. Arizona freed herself from the mud, and then withdrew south, abandoning Sachem.

The Clifton’s Battle

The battle reached its climax as Clifton closed on the fort. Because the fort was initially preoccupied with Sachem and Arizona, Clifton steamed to within 500 yards of the works unmolested. While the fort concentrated fire on the other two ships, Clifton’s 9-inch smoothbore carved huge chunks out of the dirt ramparts. But while the hits created impressive sprays of mud, they failed to disable any of the guns. Then, with the other two Federal ships out of the fight, the Irish gunners in Fort Griffin turned to Clifton.

The first salvo missed the ironclad. Only one shot of the second volley hit Clifton, but it struck astern, severing the tiller ropes. The ship slewed left, running aground in a salt marsh 300 yards from the fort. Once Clifton was grounded the fort took full advantage of her situation. As Crocker attempted to back Clifton off the bank, Confederate shot raked the ship. Shots struck the boiler so that steam and boiling water sprayed across the deck. Another shot struck the forward 9-inch gun.

Crocker attempted to keep the ship in action but was sabotaged by his subordinates and circumstance. The surgeon hid by the sternpost. The executive officer was killed, and the second officer refused to obey Crocker’s orders to fight fires. Instead, he struck the colors. Once the colors came down, the gunners, who had stood to their guns despite live steam and enemy fire, abandoned ship.

Snatching Defeat from Victory

Even then, the Federal forces could have salvaged the situation. Crocker rehoisted his flag. Arizona had finally freed herself from the shoal. Granite City and the transport Suffolk were close at hand, and six other transports, loaded with combat-ready troops, were inside the bar. One Confederate gun had been dismounted, and the rest were overheating. The Confederate gunners were tiring. No Confederate reinforcements were available, except for a five-man headquarters group in Sabine City. Resolute action—committing the remaining gunboats and landing troops from the transports—would have broken the Texan resistance.

Instead, the Granite City withdrew. As she passed the Suffolk, Lamson signaled that the Confederates were bringing up horse artillery to reinforce the fort and continued south. Unsupported, Clifton and then Sachem lowered their colors.

Franklin ordered the ships withdrawn, overriding Weitzel, who had troops in boats ready to land and felt that the Confederates could be beaten. Possibly the smoke of Uncle Ben steaming toward Sachem influenced Franklin. Possibly he believed in Lamson’s phantom horse artillery.

The withdrawal order triggered a rout. Lamson’s “Confederate battery” multiplied in the telling. Ships raced across the bar. Two ran aground and dumped cargo overboard to lighten the ships enough to clear the shoal. By 4:30 the battle was over.

Lieutenant Dowling accepted Clifton’s surrender, wading out in waist-deep water rather than allowing the Yankees ashore where they could learn the weakness of the garrison. Uncle Ben took Sachem. Twenty-eight Federal soldiers and sailors were dead, 75 seriously wounded, and over 300 taken prisoner.

Dowling’s men had no serious injuries. Several had burns from handling overheated guns or suffered minor cuts from flying debris. Two guns had been struck glancing blows, but the only gun disabled was one of the howitzers, which rolled off its platform after being fired.

The Federal fleet—less two gunboats—returned to New Orleans, the last stragglers arriving by September 10. No Union landing at Sabine Pass was ever again attempted. Instead, troops were committed to offensives along the Red River in Louisiana and Brownsville at the mouth of the Rio Grande.

Disaster for the Union; Moral Victory for the Confederates

When news of the defeat reached northeastern cities, it caused a sensation. The New York City stock exchanges fell. Combined with the defeat at Chickamauga, Sabine Pass reduced the nation’s credit rating.

At the same time, Texas gained a hero. To the beleaguered Texans, Sabine Pass was the Alamo refought, with Texas winning. Dick Dowling was hailed as the new Achilles. He spent the rest of the war recruiting on the Civil War equivalent of the War Bond tour.

Texas also gained a respite. A Federal army at Sabine City would have knocked Texas out of the war. Franklin’s 5,000 men would have been quickly reinforced to 15,000. Magruder lacked the forces to stop a Union advance over the coastal plain. Instead, Texas remained the only Confederate state whose heartland remained inviolate until after Appomattox.

Nevertheless, John Magruder had gained a new worry. He became obsessed with the notion that the Union troops would return to Sabine Pass. He moved more troops to Sabine City and dug a series of redoubts to cover the overland approaches southwest of Fort Griffin.

Over in Union-occupied territory, Franklin and Banks gained ridicule for inept leadership. Franklin’s reputation was hurt most, especially because he cited the strength of the Confederate resistance as a reason for his withdrawal. Most observers felt it ridiculous that 42 militia gunners bluffed 5,000 soldiers.

Lamson escaped punishment for his actions, as did Tibbets, commanding Arizona. Lamson did not escape the Rebels, however. Confederate forces captured him, and Granite City, on May 6, 1864—in the same inlet in which he had taken shelter eight months previously, the Calcusieu River. Tibbets and Arizona revived their reputations with outstanding service off Brownsville in the fall and winter of 1864.

Dick Dowling died of yellow fever soon after the end of the Civil War. A grateful Texas erected two statues to him, one in Hermann Park in Houston, and one where Fort Griffin once stood. Both are heroic and larger than life.

Today the battlefield is a state park. Gas and oil wells stand watch over the waters occupied by the fleeing Federal fleet. The fort is gone. The channel has been dredged, allowing deep-draft tankers access to Sabine Lake. The only token of the battle visible to the casual observer is the walking beam from the Clifton’s engine, a monument to a forgotten battle.

Mark Lardas is a freelance writer in Palestine, Texas, who has written extensively about ship modeling and naval and maritime history. He is a naval architect by training, and has worked in both space navigation and e-commerce.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments