By David H. Lippman

“In the early hours of 8 February 1945, I climbed into my command post, which consisted of a small platform halfway up a tree,” Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks wrote in his memoirs, “from where I could see in front of me a peaceful-looking valley with small farms dotted here and there. On the far side lay the sinister Reichswald Forest. Over this valley, XXX Corps was about to attack.”

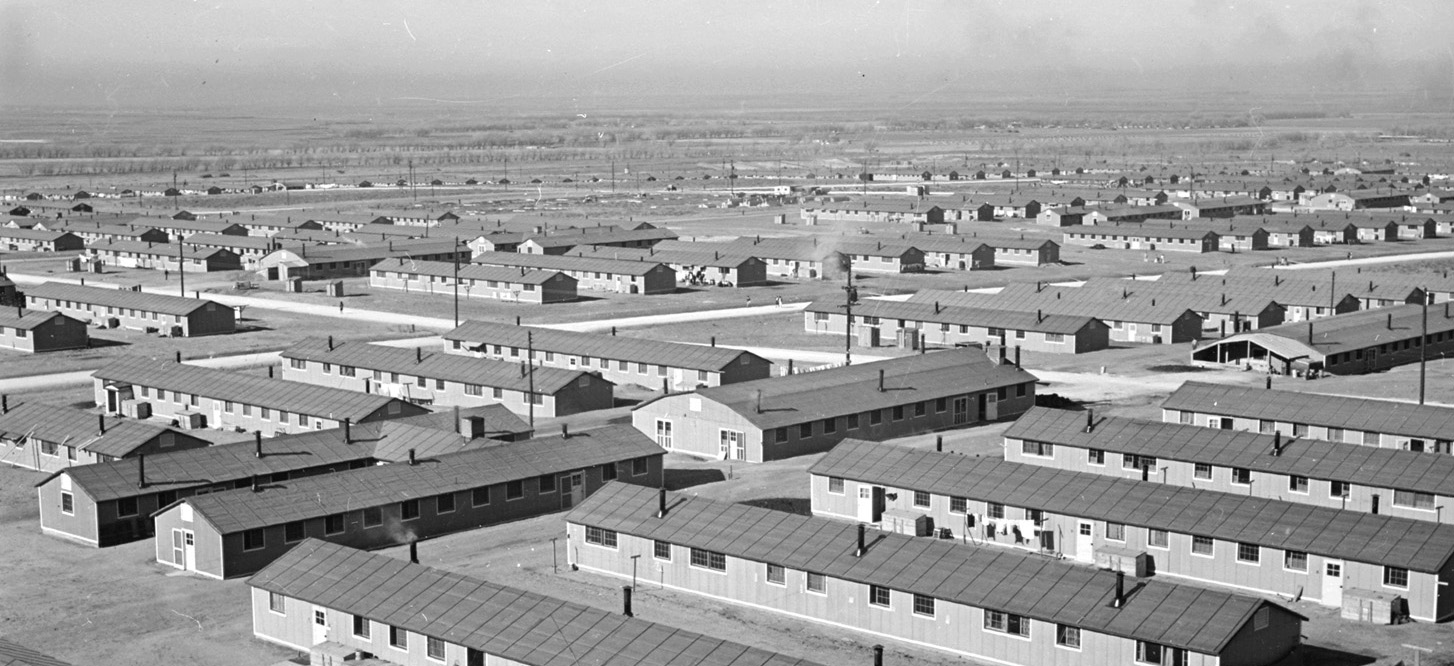

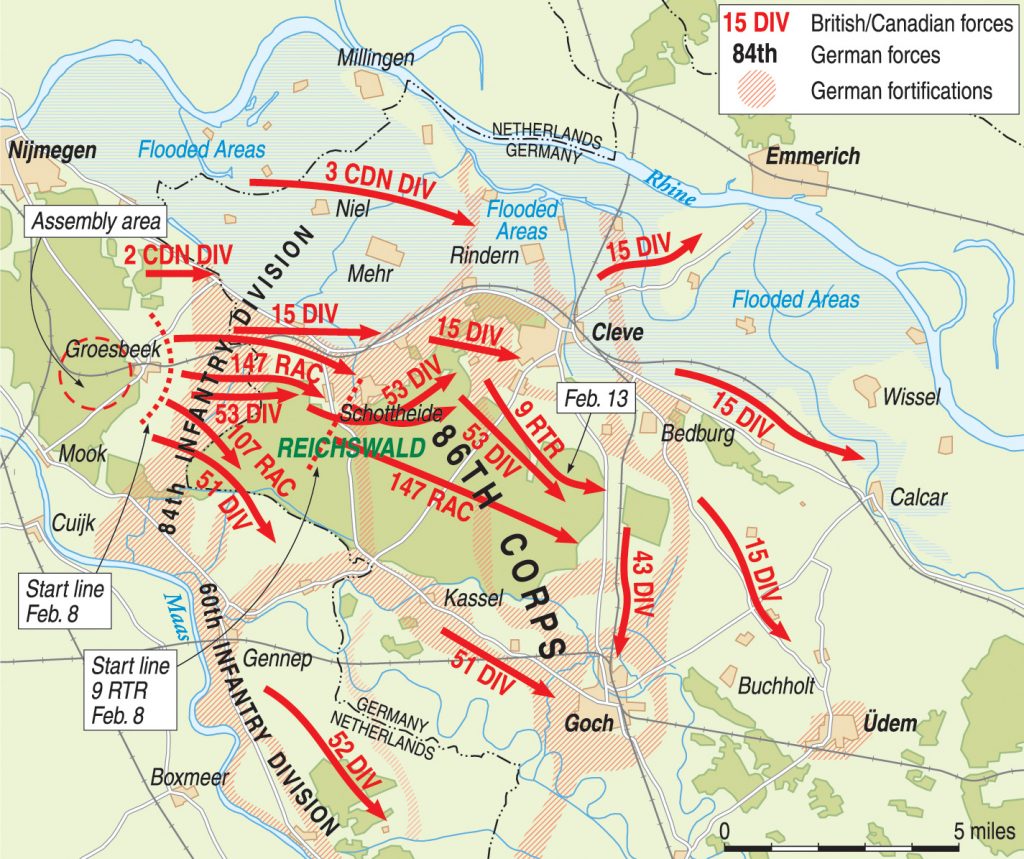

The offensive that was about to open was one of the largest battles the British and Canadians would fight in World War II, a major frontal assault designed to drive through the Reichswald Forest between the Maas and Rhine Rivers, crushing everything in its path. It was also to be the northern pincer of a grand encirclement that Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery had entrusted to the Canadian First Army under General Sir Harry Crerar, with Horrocks’ XXX Corps and its five British and two Canadian divisions, entitled Operation Veritable. The southern pincer, called Operation Grenade, would comprise 12 divisions of the U.S. Ninth Army under Lt. Gen. Bill Simpson, which would attack north across the Roer River and meet up with Horrocks’ troops. Under the plan, more than 150,000 Germans would be killed or trapped in a giant bag, and Allied troops would stand on the west bank of the Rhine River at the end of the operation. The next phase would be an equally massive crossing of the Rhine at Xanten, north of the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland, the northern pincer of an even larger encirclement of that valley of coal mines, steel mills, and factories.

But before any of that could be accomplished, Horrocks’ men had to clean out the Reichswald. That would not be easy. Despite the massive losses the Germans had suffered in the Battle of the Bulge, they remained a formidable foe. The Reichswald was a forest with valleys, hills, and two major towns, Cleve and Goch. There was only one gravel road from the Allied lines to Cleve.

In addition to those natural defenses, the Germans had begun creating a fortified line from the Reichswald to Alsace in 1938, called the Westwall by the Germans and the “Siegfried Line” by the Allies. Using one-third of Germany’s production of cement, the Westwall now consisted of more than 3,000 concrete pillboxes, bunkers, and observation posts strung two or three lines deep.

The pillboxes themselves were eight feet thick, with small rooms for fortress troops, ammunition storage, and gun emplacements, some camouflaged in houses and barns. Everywhere were concrete “dragon’s teeth”—anti-tank obstacles—and anti-tank ditches.

These impressive defenses, though, required troops. In the Reichswald, that meant the veteran paratrooper General Alfred Schlemm, who commanded the 1st Parachute Army. While it had parachute divisions on its ration strength, few of them were actually jump-trained. They were, however, highly skilled battlefield soldiers with high morale and expertise in last-ditch stands. The direct defender of the Reichswald was the 86th Infantry Corps under General Erich Straube, known behind his back as the Uhrmacher, the Watchmaker, for his obsession with detail. Despite that, Straube had fought well on the Eastern Front and was a master of the fighting withdrawal, something the Germans would need in the upcoming battle. Straube was competent and caustic.

Under his command on the Reichswald front line stood the 84th Infantry Division, consisting of 10,000 men in three regiments. This outfit had been formed in occupied Poland in March 1944 from various scrapings of units battered on the Eastern Front. Since then, it had been shredded at Falaise in August, then taken a pounding from American paratroopers in Holland that September, and now consisted of some veteran soldiers, naval personnel released from bases and immobile ships, and 17-year-old kids. It had the 276th Mogen or “Stomach” Battalion—men whose stomach issues required a special diet—under its command, and an Ohren or “Ear” Battalion, consisting of deaf men who were not put on the front lines. The 84th had 36 self-propelled antitank guns of the 655th Heavy Antitank Battalion and only 100 artillery pieces, most of them horse-drawn. The division’s boss was six-foot-tall Maj. Gen. Heinz Fiebig, described by other German officers as “striking and … debonair” and “a charming fellow to have at a party [but] the last man to lead a division in the field.”

Part of the front was held by the 2nd Parachute Regiment. For reserves, Straube could call on the 7th Parachute Division, the 15th Panzergrenadier Division, and the 116th Panzer Division, then refitting after being mauled in the Battle of the Bulge. There was virtually no air cover. The Luftwaffe counted its aircraft in handfuls and lacked the fuel to show them to the enemy.

The Watchmaker had added to his defensive positions. A fortified line between the flooded areas south of the Rhine and the Maas added a double series of trenches and antitank ditches. Behind that was the Westwall, which included defenses around Cleve and Goch. Behind that was yet another line, the Hochwald Layback, a backup with more trenches, wire belts, and mines.

The four-mile-wide Reichswald itself provided plenty of natural defenses: flooded land south of the Rhine; thick woods; narrow trails that went north to south, perpendicular to the planned advance; and most of all, soft soil, which would turn into mud under thaw and rain. Most of the woods consisted of young pine four to seven feet apart. Along the northern flank and within its tree line, the Materborn Ridge ranged between 200 and 250 feet above sea level before pivoting in the northwest corner. There, it created a 300-foot hill called the Brandenberg, which provided artillery spotters with a perfect box seat for the whole area.

Now Horrocks and Crerar prepared their plans and supplies for the massive assault. A contingent of 470,000 British and Canadian troops would assault the German defenses, ranging from Tommies in battle-dress to Canadian psychiatrists to deal with shell-shock. This would be the largest single offensive since the Normandy landings and breakout, and the British were determined to avoid the embarrassment of the Market Garden fiasco in Holland in September.

To address the road issue, 50 companies of Royal Engineers, 20 more of pioneers, and three road-construction companies worked around the clock to shore up and rebuild 400 miles of roads and construct 100 miles of new ones. The engineers also built 100 new bridges, including five across the Maas, among them a 1,280-foot-long one named Quebec, and a rail bridge near Nijmegen.

The British could also turn to the specialized armor of the 79th Armored Division and its so-called “funnies.” These were highly unusual tanks: Churchill “Crocodile” flamethrowers, “Petard” tanks that fired immense shells at close range to blast open bunkers, Sherman Flails or “Crabs,” which had a rotating drum in front of their hulls with revolving flails designed to set off anti-personnel mines and thus create a path through hostile minefields. The division also had the world’s first armored personnel carrier, the Kangaroo, which was used by Canadian infantry, and amphibious Weasels, Buffaloes, and DUKWs that could carry troops through flooded terrain.

This attack would also rely on the major Allied trump card: overwhelming airpower.

With D-Day set for February 8, Crerar had a big question for Horrocks: “Do you want Cleve taken out?” For Horrocks, agreeing to do so would mean that Bomber Command’s Lancasters would pummel Cleve with their “cookies” and incendiary bombs, turning the ancient walled and historic city to a moonscape of rubble. It was a tough call for Horrocks, who knew that the city had a historic past and civilians living in it in the present. “Their fate depended on how I answered Crerar’s question, and I simply hated the thought of Cleve being ‘taken out.’ All the same, if we were going to break out of the bottleneck into the German plain, it was a race between the German reserves and the (15th Scottish) Division for the Nutterden Feature (a fortified choke point through which the Nijmegen-Cleve road ran), and the German reserves would have to come through Cleve. If I could delay them by bombing it might make all the difference to the battle, and, after all, the lives of my own troops must come first. So I said ‘Yes,’ the most terrific decision I had ever had to take in my life, and I can assure you that I felt almost physically sick when, on the night before the attack, I saw the bombers overhead on their deadly mission.”

With preparations accomplished, only two things remained to be done: select a date and brief the troops. The date was weather-dependent. Crerar and Horrocks decided to cut Bomber Command loose on the night of February 7 and then hurl the ground forces into action the following morning, February 8. On the evening of the 7th, battalion and company commanders were briefed on the pending attacks and given pep messages from Montgomery and Crerar. Monty called the upcoming battle a boxing match, finishing, “Into the ring, then, let us go. And do not let us relax till the knockout blow has been delivered. Good luck to you all and God bless you.”

Bomber Command’s 4, 6 Canadian, and 8 Group dispatched 292 Halifax, 156 Lancaster, and 16 Mosquito bombers to hammer Cleve and Goch. The two towns were blasted in a mere 20 minutes. Thirty German civilians and about 150 slave laborers, mostly Russians, Italians, and Dutchmen, quartered in two schools, were killed. The number of German troops killed is unknown.

At the same time, low-hanging clouds threatening rain were gathering over the whole area. This was going to turn the ground to mud and inhibit armored forces.

While the bombers pounded away, British and Canadian troops filtered into their start lines, drank tea and ate sandwiches, wrote letters to their families, and checked their gear. The attacking British infantry were well-equipped themselves: reliable .303 Lee-Enfield rifles, Sten sub-machine guns that could withstand heavy mud, Bren machine guns that spewed out heavy rates of fire, and Personal Infantry Antitank (PIAT) launchers. Nearly every Tommy seemed to have a shovel on his back to quickly dig a foxhole in case of counterfire.

From right to left, the attackers would be the 51st Highland Division, the 53rd Welsh Division, the 15th Scottish in the center, the 2nd Canadians after that, and the 3rd Canadians on the extreme left. In immediate reserve were the 43rd Wessex Division and the Guards Armored Division. Directly supporting the assault troops were the three brigades of the 79th Armored Division.

Now, at 5 AM on February 8, Horrocks sat in his platform, connected by scout-car radio sets with the division and brigade command posts ahead of him. “From my viewpoint, I could follow the progress of the attacks by the lifts in the barrage,” Horrocks wrote later. He stared eastward into the German lines and a fading drizzle.

So did thousands of British and Canadian troops, most intently 9,000 gunners who had loaded their artillery pieces in the dark by flashlight. Among them was Canadian artillery Captain George Blackburn, observing his gun crews stacking piles of shells next to their guns, removing safety caps from them, and winching their guns into position. Th 5,000 tons of high explosives they were about to hurl at the Germans would be the single heaviest British artillery barrage of the entire war.

At 5 AM, the order to fire was given up and down the Anglo-Canadian line, and every piece XXX Corps had opened up on the Germans. A Royal Dragoon guardsman, wireless operator A.E. Baker, recalled: “At one minute to five that morning, everything was peaceful. It was still dark and there was a slight mist. At 5:00, all hell broke loose! It was as bright as day, and the noise was like nothing on earth…At 5:30, as arranged, the tanks began to fire…The row was absolutely beyond belief, and long before it finished, I had a splitting headache. It wasn’t only the concussion of the bigger guns but the ceaseless, sharp hammering of the Vickers just beside our tank.”

Major Francis “Knobby” Clarke, B Company commander, and C Company’s Major John Campbell promised each other to “have our rum together in the Wyler church” in the distance. Lieutenant Howard Powell, the battalion’s intelligence officer, watched as rockets blasted a farm and grove of trees ahead of Wyler, their objective. “I never saw anything like that in my life. The ground just rocked…That place disintegrated, all in one smack,” he said later.

From 5 AM until 7:30 AM, the British and Canadians shelled the Germans. The 7.2-inch howitzers and 8-inch “super-heavy” guns hurled 200-pound shells on German bunkers 14 miles from the frontline. The 3.7-inch antiaircraft guns fired shells on flat trajectories, delivering 20-pound airburst shells over German trenches, scattering shrapnel everywhere. The noise was so great that artillery spotters could not converse by phone with their command posts, nor could gunners at their weapons.

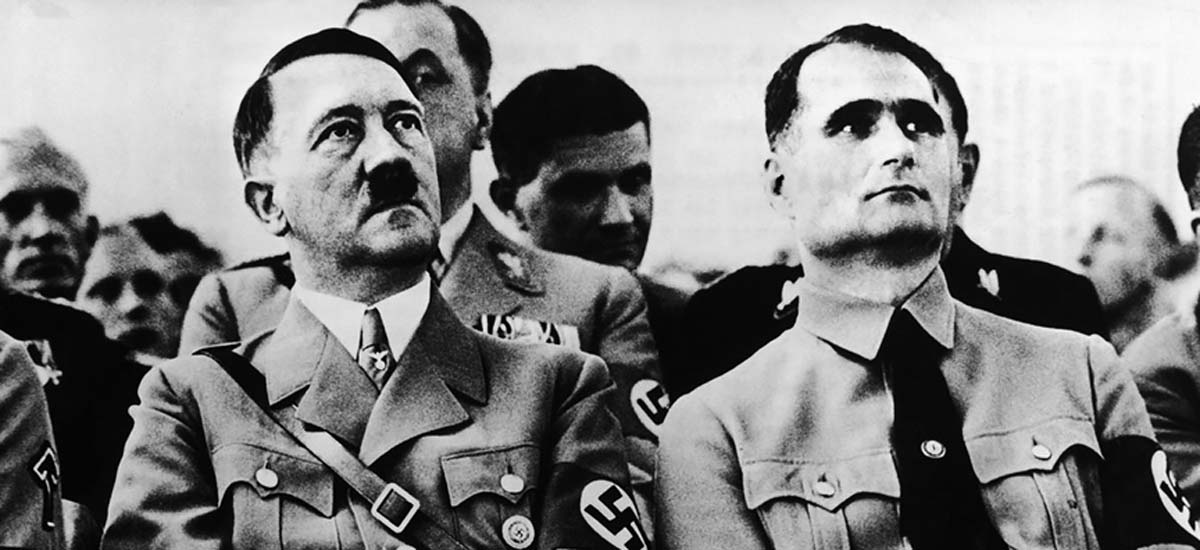

The heavy bombardment woke up General Schlemm at his Xanten headquarters. He climbed to the top of one of the twin towers of the Romanesque St. Victor’s Cathedral and studied the sky to the west coming alight in flashes of vermilion and gold. He signaled his superior, Army Group H commander General Johannes Blaskowitz, “I smell the big offensive.” He summoned the 6th and 7th Parachute Divisions to firm up the 84th Division’s defenses and fired off a message to Berlin, where Adolf Hitler and his top aides held an emergency meeting to discuss the onslaught.

At 7:30 AM, the mighty British bombardment came to a halt. The noise was replaced by the crackle of burning forest and the cries of wounded Germans. Cleve still burned, glowing crimson. Twisted and shattered trees, wrecked farm buildings, and slaughtered farm animals provided an obscene decoration to the ground.

British artillery replaced the gunfire with a mighty smokescreen 13,500 yards long, and surviving German defenders naturally assumed that it was cover for an impending British assault. They jumped back into their trenches, re-manned weapons, shouted orders, removed corpses, reconnected barbed wire and telephone lines, and opened fire on the Tommies they presumed were coming.

They presumed wrong. British and Canadian artillery spotters and sound locators homed in on the Germans and reported the targets back to their gunners. Once again, the British guns blazed away, this time at the new targets. The going was tougher for the artillerymen. One round left in an overheated breech exploded, splitting the barrel. The new gun layer had just slipped off his seat to stretch his legs, which saved his life.

The British and Canadian gunners continued to hammer the Germans into the morning, blasting away. While they did, tanks and armored vehicles clattered past the howitzers, headed for the XXX Corps start line, shuffling down roads and trails past the ghostly wreckage of crashed gliders of the 82nd Airborne Division from the September 1944 Market Garden assault that had been too shattered to salvage. Hot tank exhausts were covered by fluorescent panels to identify them to British and Canadian aircraft, and all were stripped for action, except one tank that still had a frying pan hanging from the back of its turret.

The shelling continued until 10:30 AM, H-Hour for the assault, as 60,000 troops, 500 regular tanks, and 500 specialized tanks stood on their start lines. At that time, the shelling stopped, and the heavy guns once again opened up with a barrage of smoke shells.

This time, the Germans did not retaliate, having endured one barrage after a smokescreen already. They waited in their battered pits and in the mud.

The British attack opened on the right flank with the 51st Highland Division, the men of which marked their vehicles, routes, and successes by posting the division’s “HD” symbol everywhere. Scornful Tommies called them the “Highway Decorators.”

Now the Highway Decorators moved carefully into the southwest corner of the Reichswald on a 5,000-yard front, advancing eastward. Legendary battalions like the 1st Black Watch, the 5/7th Gordons, and the 5th Seaforths led the assault, many men wearing white snowsuits to blend in. Privates Stan Whitehouse and “Shorty” Shorthouse of the 1st Black Watch had been reluctant to accept sergeant’s stripes, but they sewed them on now, knowing that their platoon had been worn down by years of war from El Alamein to Germany, and many of the men were either replacements or exhausted veterans who had never learned or forgotten how to dig in, camouflage themselves, and recognize minefields and booby traps.

The 51st Division got down to business with the 72 Vickers machine guns of 1st/7th Middlesex, the “Die Hards,” firing off seven million rounds of ammunition. With that, the 1st and 7th Black Watch reached the start line, and the 1st Black Watch promptly became the first Highland Division men to enter Germany, screened by mortar smoke.

Major Thomas Landale Rollo, checking the 7th Black Watch start line, saw his old friend, D Company’s commander, Major Allan Lowe come up. The two shook hands, and Rollo said, “I’ll see you soon.”

Lowe replied, “You’ll never see me again. I’m going to be killed.”

“Of course, I replied, ‘Don’t talk nonsense,’” Rollo said later. “But it shakes you. Two nights before, he had cleared out and gone away to Brussels, unknown to anybody. When I saw him later, he said it was ‘the last chance I’ll ever get.’ It wasn’t that he was depressed. He was completely in control of himself. Yet he had a feeling that that was it.

“Allan crossed the start line. He had his signaler with him carrying the wireless. It was a mad thing to do because the Boche picked up right away who the commander was. Within 200 yards, a bullet went right through him,” Rollo recalled.

Nor did smoke interfere with Schu mines, as newly promoted Sergeant Stan Whitehouse watched in horror as Corporal Aitchison was blown up by one. “His Sten flew out of his hands and on landing set off another mine. ‘Bastard things,’ I thought.” A “friendly” shell dropped on Company HQ, and Whitehouse was ordered back to collect a Bren and mortar from wounded men behind. “I was horrified to see Ken Ware, eyes glazing over, his face creased with pain and his limbs shattered. Blood, a strange, light brownish color was bubbling out of his legs. Larry Crowther, his best mate, lay nearby, in an equally hopeless condition. Ken and Larry, two of the most gentle, lovable things ever born, now lay in bits and pieces.”

To make the day more difficult, some British shells fell as much as 300 yards short despite the gunners’ best efforts. The bursts killed Highlanders and turned tree limbs into deadly shrapnel.

After advancing only a few hundred yards, B Company of the 5th Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, Major Donald Callander commanding, came under Panzerfaust and machine-gun fire. Everyone hit the dirt, and Callander ordered his men to right-flank the Germans. The Scots moved, and someone yelled, “The company commander’s hit!”

Callander leaped up and yelled, “I’m bloody well not!” What had been hit was his mess tin (a German bullet went through it), but three other Camerons were indeed killed. Callander led two platoons in a flanking bayonet charge across a 50-yard clearing. He jumped out of a ditch, looked back, and saw a German shooting at his men, his back to Callander. The major whirled, shot the German, and maintained the advance.

Lieutenant Ross Le Mesurier, a 21-year-old Canadian officer leading a platoon of B Company, spent only 24 hours in the Reichswald and advanced only one mile but fought with heroism and distinction. He had already been wounded three times: a sniper bullet through his tin hat to crease his head, a piece of shrapnel lodged in his back, a fragment puncturing his arm. “Just nicks,” Le Mesurier told Callander.

As the day wore on, the two lead Highland Brigades, the 153rd and 154th, were joined by their reserve brigade, the 152nd, but all three brigades found the rain was turning the trails into muddy quagmires that would support neither wheeled nor tracked vehicles. The Scots had to leave them behind and plod on through the mud.

As night fell, the 5th Queen’s Own Camerons’ Company B kept attacking through a tremendous downpour. Each man held onto the bayonet scabbard of the Scot in front of him to avoid getting lost. Ahead lay B Company’s objective, a track crossing the mud. On this track, German troops were laying mines when the Scots showed up. The Germans reacted with alacrity, opening fire with Panzerfausts, hitting Callander’s signaler. Callander yelled at Le Mesurier, “For Christ’s sake, Ross, you’ve got to do something!”

Ross grabbed a phosphorous grenade, intending to hurl it at the Germans, but as he was about to throw the grenade a German bullet hit it and caused it to explode in Le Mesurier’s face. A blob of phosphorous hit his glasses, which saved Le Mesurier’s vision, but he had to scoop up handfuls of muddy snow to stop the burning sensation.

As the Germans advanced toward Le Mesurier’s men, he ordered his own platoon to charge, dropping to one knee to fire his Sten gun. To his horror, the Sten gun jammed, a typical failing with the weapon. He threw it down, “grabbed his entrenching tool, and went roaring off after the Germans,” Callander said later. “He was a big man, Ross, and when he ran at them screaming like a madman and waving the shovel, the enemy took off!”

“I remember hitting one of them in the back of the neck,” Le Mesurier said later. “He crumpled. I thought he was dead. I swung at another, just a glancing blow on the shoulder, but he kept going in the dark. I was getting too far in front of my boys by then, so I figured I’d better get back to my platoon.”

Callander found Le Mesurier returning, with phosphorous glowing from his uniform. Callander ordered Le Mesurier to go to the rear, but the platoon commander refused to do so, as the other two platoon commanders had been killed. “I’ll see you through, Donald,” Le Mesurier said. He would not be evacuated until the next day, his war finished.

“I put him up for a Military Cross,” Callander said. “It should have been a Victoria Cross.”

Another Canadian with the 51st, Captain Maurice Carter, who commanded a 2nd Seaforths company, was having a trying time. The Seaforths were used to open warfare, not forests, and they ran smack into heavy machine-gun fire on opposite sides of the line of advance and were stopped cold.

Major Martin Lindsay and his 1st Gordons climbed a ridge. “The wood was jungle, so many branches and trees having been felled by our shelling. We might have been in darkest Africa. Every hundred yards took us about 15 minutes, and the confusion was indescribable,” he said.

To the left of the Highland Division, the Welshmen of the 53rd Division drew the actual drive into the Reichswald Forest. Fortunately, they were well trained in narrow-front assaults into forests, had tested the tactics in the Battle of the Bulge, and had outstanding support from their logistical and transport teams. The 1st East Lancashire Regiment’s history reported: “An almost overpowering smell of spent explosive hung like a cloud in the forest. Trees lay smashed and shattered, their broken branches strewn about, leaving stumps standing like grotesque scarecrows to discourage invaders.”

Terrain and mud held back the 79th Armored’s specialized tanks, turning over the battle to the infantry. The 53rd Division’s history reported, “It was Spandau versus Bren the whole way through.”

North of the 53rd, six-foot-tall Maj. Gen. “Tiny” Barber’s 15th Scottish Division charged into battle. The 227th and 46th Brigades moved in through the rain and initially gained successes, the Glasgow Highlanders alone taking 146 prisoners. The rain, unfortunately, turned the ground to mud, imprisoning the tanks of the Coldstream Guards. The Camerons took over, suffered casualties in a minefield, but captured 48 more Germans and a battery of 88mm antitank guns. Flame-throwing Crocodile tanks torched German-held houses in Frasselt.

On the left flank of the 15th Division’s attack, the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and Highland Light Infantry led the assault. It was the first set-piece battle for the Argylls since Normandy, and their commander was on leave, so Major Goodwyn commanded them. The Argylls ate breakfast, had a tot of rum, and then rode into battle on the backs of the 3rd Scots Guards’ Churchill tanks. An old American minefield, a stream, and boggy ground slowed the armor. Company B lost seven men to a thick minefield. Company A took heavy defensive fire that killed or wounded all the officers. Company Sergeant Major Green immediately took command, rallied the company, and was awarded an immediate Distinguished Conduct Medal. Canadian land mattress rockets pounded Company A’s objective, the Elsenhof, into rubble, and the Scots took 80 prisoners. Company C did the same. Both battalions cleared the town of Krakenburg and then consolidated to await a German counterattack. For once, it didn’t come. The shell-shocked Germans could neither communicate orders nor muster men.

Despite heavy rain, mud, and appalling road conditions, the 15th Scottish had achieved its objectives. By 6:30 PM, though, the tracks were impassible.

Just north of the 15th Scottish, the 2nd Canadian Division attacked with its 5th Infantry Brigade on a two-battalion front, sending the Calgary Highlanders and the Francophone Le Régiment de Maisonneuve forward. The 2nd Division had taken a beating at Dieppe in 1942, and survivors and replacements alike had much to avenge. Backed by the flails of the British 13th/18th Hussars, the two battalions were to head past Wyler on the south, cut the road from behind it, and attack from the rear. This “fan-wise sweep with the left wheel movement” would be executed by the Highlanders’ C and D Companies, while the “Maisies” would screen their assault and grab the town of Hochstrasse. The 5th Brigade’s Brigadier Bill Megill knew that Wyler and its neighboring town of Den Heuvel would be well defended, not just because of the rain and mud, but because of its strongpoints and minefields.

At 10:30 PM, two Maisonneuve companies headed for Den Heuvel, close behind their artillery barrage. They found dugouts and fortified buildings, and a close-quarter firefight soon raged. Major Francois de Salle Robert’s D Company entered the village and was hit by rifle fire from behind. Wireless signaler Joseph Lefebvre spotted the source of the shooting. He shoved his No. 18 wireless set into the hands of another signaler, grabbed a Sten gun and four grenades, and worked his way back to a dugout the company had missed while moving up. He threw a grenade into the building and demanded the Germans surrender. No response. Lefebvre threw two more grenades and charged into the building, firing his Sten gun. He emerged with four POWs and a number of Germans left behind, dead. Lefebvre received a Military Medal for the feat.

The Maisies found many Den Heuvel defenders dazed by the immense bombardment. A German officer stumbled out of a house, hands up, muttering, “It was terrible.” A Maisonneuve officer found 45 German bodies strewn about in a small area. More lay inside bunkers and trenches. A Canadian found a letter that a German frontkämpfer (frontline troop) had written just as the attack started, which read: “When Tommy began his attack, he started such a terrific artillery barrage that we took leave of our senses. I shall not forget my experience in the Reichswald for a long time.”

The surviving German POWs shuffled in motley, mud-covered columns into Canadian lines, where the Toronto Scottish Machine Gun Regiment stood waiting by the fuming muzzles of their powerful Vickers machine guns. Their commander, Lt. Col. E.G. Johnson, wrote that many prisoners were “completely addled.” He noted that their guards reported that many simply emerged “out of their trenches with…hands up and offering no resistance to our troops.”

A less exalted Canadian gunner, J.P. Brady of the 4th Medium Regiment, wrote, “British corpses are being brought back lashed to the tops of ambulance jeeps…Later, long lines of prisoners come in. Some reel drunkenly, others stare vacantly. Some shamble along in tears, while others laugh hysterically. The prisoners who are articulate say they were overwhelmed by an annihilating fire and could not make a defensive stand in their front line.” The Highlanders and intelligence officers searched their captives thoroughly for weapons, souvenirs, and information. One embarrassing moment came when a defending German soldier turned out to be female. The intelligence officer who discovered this walked around with a flushed expression.

At 11:23, the Maisies reported Den Heuvel secure and headed for the German border. Now they took more casualties. Private Albert Lacoste was killed two weeks short of his 20th birthday. Sniper Private Hector Lefebvre and his pals came under heavy machine-gun fire. Lefebvre “worked his way to a vantage point. Still under fire, he coolly pinpointed the enemy machine-gun post and successfully silenced it, killing one and wounding two of the crew,” as his Military Medal citation stated.

Lieutenant Louis Fontaine, weakened by his wounds, led one of his men to close with the German machine gun that was causing his men to hit the dirt and put it out of action. Fontaine refused to be evacuated for two hours. He earned a Military Cross.

The Calgary Highlanders had a harder time. They started off 12 minutes later, plodded through the mud and German minefields, and came under mortar fire. The combination wiped out a leading section’s leaders, except for Lance Cpl. Robert Allan McMahon. Seeing that the rest of his buddies were leaderless, McMahon picked past the mines and ran into the buildings from where the German fire was coming. Inside them, McMahon killed a number of Germans, wounded several others, and took one officer and 22 men prisoner. When McMahon took them out, he ordered them to carry the wounded. An infuriated German officer “attempted to stir up an insurrection.” According to McMahon’s Distinguish Conduct Medal citation, he “stopped [this] with his fists.” Two of these German POWs stepped on their own mines and were killed.

Meanwhile, McMahon’s platoon leader, Sergeant Carol Edwin Anderson, ran across the battlefield, giving first aid to wounded men and warning medics coming up behind that they risked death from the German mines.

With that done, Anderson led his surviving men to Vossendaal, coming under more machine-gun fire. Canadian Bren gunners fired back, and Anderson rushed the German MG42, killing its four-man crew with Sten gun bursts and grenades. The platoon resumed the advance and came under more machine-gun fire. Anderson crawled forward and killed the German machine gunners, and then he led his platoon to their final objective. For these feats, he earned a Military Medal.

Another dedicated and decorated Highlander, Sergeant Emile Jean “Blackie” Laloge, led D Company’s platoon into intense mortar fire. The commander of the platoon ahead was killed, and everybody hit the dirt. Knowing that hesitation could be fatal, he shouted at his platoon to keep moving. He led his men through the frozen platoon ahead and straight at the Germans, realizing it was impossible to outflank them. Laloge led by example, charging into the German machine gunners and gunning them down.

That accomplished, Laloge led a section up the road, coming under more Spandau fire. Laloge made himself the target so that his section could flank and overrun the gun, taking the crew prisoner. Incredibly, Laloge was uninjured, although his uniform was shredded. He added a Military Medal to adorn that battered uniform.

Major John Campbell’s C Company headed down a small secondary road into Wyler from the southeast and faced the usual minefields, machine-gun fire, and mortar bombardment. The assault route was a German trap, and Campbell himself was killed by a sniper. Campbell would never have his rum with his pal “Knobby” Clarke. Lieutenant Ed Ford of 14 Platoon took over. Grabbing the wireless set, he received a call asking if he wanted artillery support. Fearing that such fire would fall “short” and on his men’s heads, he said, “No, it’s an infantry job.” He wanted reinforcements.

While he waited for backup to arrive, Ford realized the Germans in the overlooking building had to be eliminated. He shouted at Sergeant Michael Melnychenko, commanding 13 Platoon, to take over the company, while Ford and 13 Platoon made the attack as 14 Platoon gave covering fire.

Ford led a few men to the buildings, chasing the Germans out of them or killing them. Luckily, the Highlanders were sorting things out as 5th Field Regiment had a new fire plan for its 25-pound artillery pieces supporting the position. The Toronto Scottish’s 4.2-inch mortars were ready to fire, and best of all, B Company was moving up to a start line to resume the attack in C Company’s sector.

Melnychenko was told to take his remaining six men and secure that start line. The seven Highlanders crawled into a network of German trenches, killing or capturing all Germans in their path and silencing three Spandaus. They found a house filled with snipers, and Melnychenko ordered his PIAT team to fire a 2.5-pound round into the building. Melnychenko and three men raced around the house, into a door, killed two snipers, and captured the remaining 18 defenders. With that, B Company, aided by fire support, was able to get moving. Melnychenko received a Military Medal.

At 5:25 PM, Canadian artillery and mortars began to hammer Wyler, and D and B Companies started clearing it in a coordinated manner. By 5:45, the town was clear, even if the weather wasn’t (a cold rain was falling). The Calgary Highlanders had lost two officers and 11 other ranks and suffered one officer and 60 other ranks wounded, 40 percent of the casualties to mines.

As the dusk gathered, the 7th Field Company of Royal Canadian Engineers began working to open the road from Wyler to Cleve, removing mines despite German sniper fire. They were done by 9 PM. The 2nd Canadian Division was finished with the opening phase of Veritable.

The last Canadian division to lead off the attack in Veritable was the 3rd Division, under Maj. Gen. Dan Spry, doing so at 6 PM. The 3rd Division was one of the five Allied divisions that had stormed Normandy’s beaches on D-Day and had compiled a long battle record since then. Their front lay between the Nijmegen-Cleve road and the Rhine River. The bad news was that the Germans had flooded the area, and it was completely underwater. The good news was that so were the German minefields, anti-tank ditches, and wire barriers. The Canadians would ride into battle on 114 amphibious Buffaloes and 50 Weasels of the 79th Armored Division.

Spry had just turned 32 on February 4 and was the youngest general in the Allied forces. He was also a Boy Scout fan and modeled his behavior on their best values, which included temperate speech and manner, as well as working to keep his men alive.

As with all the other assaults that day, the Canadians planned the attack in grand triangles. The 7th Brigade attacked with the Regina Rifles and Canadian Scottish on the right, with 8th Brigade’s North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment and La Régiment de la Chaudiére on the left.

The major 7th Brigade objective was the mile-long Quer Damm, which the Germans had fortified with strongpoints, including one that Allied intelligence officers named “Little Tobruk.” The Canadian Scots were assigned this objective. The Germans had weakened the dam with all their construction, and on the morning of February 8, a section of it collapsed, sending water rushing into the villages of Zyfflich and Leuth. The former was the Regina Rifles’ objective beyond the dam.

The massive flooding forced 8th Brigade’s commander, Brigadier Jim Roberts, to make an unpleasant decision: withdraw. He explained later that in “actual combat, it is wise to keep your plan simple. Too detailed a plan usually comes unstuck. And yet, in my plan for 8th Brigade, it was very difficult to be simple, given the flood conditions of the terrain. The flood waters were rising every hour.”

Roberts decided to launch his attack at 6 PM, when it would be dark. His Buffaloes would have better concealment, but his drivers and officers could get lost in the dark and rain. Two North Shore companies would ride Buffaloes across the flooded terrain to a dike running north from the Quer Damm to the Rhine while the Chaudiéres would send an assault team in eight-man canoe-like “skiffs” and paddle to a flooded orchard. There they would wait until the North Shores signaled with a flashing light that they were in place. Once that was accomplished, the two battalions would form the juncture with the Quer Damm.

It was a complicated plan, which had required night movement amid heavy rain, flooding, and alert German forces. Roberts, though, saw it as “the great opportunity for the final breakthrough into Hitler’s Germany.”

Canadian artillery provided a pepper pot of “unbelievable power and noise on the German position,” according to Roberts, and the brigade crossed its start lines. When the Buffaloes roared hard into the wet earth, though, they dug themselves into the embankment and were stuck. The British major in charge jumped out and began giving orders. Roberts jumped on his wireless and asked for the artillery fire to continue, then dashed down to the major, urging him to try to reverse the Buffaloes and enter the water on a diagonal slope. It worked.

On their skiffs, the “Chauds” pushed off, with A and D Companies in the lead. As A Company’s second-in-command, Captain Leo Larose, pushed off, a shell exploded in a nearby airburst, ripping shrapnel through the skiff. Nobody was hurt, but Larose ordered everyone to paddle to a half-submerged farmhouse nearby. They just got in through a window as the skiff sank.

Otherwise, the attack went as planned, with 8th Brigade reaching the dike by boat and Buffalo. The defenders turned out to be a hapless collection of locally recruited Volkssturm militia. “Most of them World War I veterans, with Mauser rifles of their generation, gray grizzled beards, and a look of dazed shock on their faces. No wonder, considering the terrific bombardment they had received for a full 20 minutes! They came out of their dugout, not with their arms raised in surrender, but holding their ears with their hands, rolling their heads from side to side, and drooling at the mouth,” Roberts wrote.

The first day of Operation Veritable was over. The British and Canadians had delivered more than 8,000 tons of shells on the Germans. Despite rain, fog, machine guns, and mortars, the British and Canadians had crushed six battalions of the 84th Infantry Division, suffered almost no casualties from “shorts,” and taken 1,115 prisoners for a loss of 349 Canadians and Britons. The total of German dead was difficult to count. The advancing troops found German telephone lines wrecked and gun positions mangled. Captured German officers told their interrogators that they could not give orders to their men. All the 84th could do was hold out in disjointed positions until their men died or surrendered. All the concrete works had been destroyed.

The victory was still far from complete, or the battle even won. Rain continued to pour down on the Reichswald. Tanks, trucks, and other vehicles were trapped in the mud. The water level north of the Nijmegen-Cleve road rose 18 inches after midnight on the 8th. The American side of the grand pincers, Operation Grenade, had yet to be launched.

The offensive still had to be maintained to achieve success. So Horrocks made what he would describe as one of his worst mistakes of the war. With the 15th Scottish Division closing in on Cleve, Horrocks called for his reserve, the 43rd Wessex Division, to move up to pass through the 15th Scottish and burst out into the plain. It was a determined decision, but it meant that the horrific fighting in the “Sinister Valley” would only become worse for the British and Canadian infantrymen struggling in it.

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History. This is the first of a two-part article on the Battle of the Reichswald. Part two will appear in the October issue.