By Michael D. Hull

As in thousands of other homes across America, there was an air of tension in the living room of the modest frame house at 98 Adams Street, Waterloo, Iowa, on the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, 1941.

A radio announcer was breathlessly relating sparse details of the sudden Japanese attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, early that morning. The Sullivan family, like many others from Maine to California, was stunned.

Mrs. Alleta Sullivan cried softly, and her husband, railroad man Thomas F. Sullivan, tried to comfort her. Mrs. Sullivan knew that her five sons would have to go to war.

“If It Comes to the Worst, Why, We’ll Be Together in That, Too”

The Des Moines Register Sunday sports and comics sections had been pushed aside, and the boys sat around the living room table, listening intently to the radio. They were George Thomas, born on December 14, 1914; Francis Henry, born February 18, 1916; Joseph Eugene, born August 28, 1918; Madison Abel, born November 8, 1919; and Albert Leo, born July 8, 1922. Albert was the “baby” and the only married son.

George turned to his brothers and said purposefully, “Well, fellas, I guess this settles it. You know what we’ve been saying we’d do if something like this ever happened. And we’re going to do it together, and if it comes to the worst, why, we’ll be together in that, too.”

He was talking about the Navy. George and Francis had completed four-year hitches as bluejackets a few months earlier. The brothers had recently been working at the Rath Packing Co., a large Waterloo meat concern.

So the five Sullivan brothers quickly agreed to enlist in the Navy—together. Their fearful parents agreed. The boys had always been together at play and at school in the Adams Street-Logan Avenue neighborhood of Waterloo. They had not been quarrelsome lads, but few of their peers wanted to tangle with the Sullivan boys. They always fought together.

Tom Sullivan, a graying, slightly built man, had worked long and hard as a brakeman and conductor on the Illinois Central Railroad to keep his family fed and clothed during the Great Depression. He and his wife were proud of their sons and daughter Genevieve. Theirs was a close-knit Roman Catholic family.

After learning that a friend, Seaman First Class William V. Ball of Fredericksburg, Iowa, had gone down with the battleship USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor, the Sullivan brothers wasted no time. They quit their jobs, packed their suitcases, hugged their tearful parents, and trudged off in the snow to enlist at Des Moines on January 3, 1942.

Assigned to the USS Juneau

The five told Navy recruiting officers that they insisted on serving together, although it was against regulations. They were sent to the Naval Training Center at Great Lakes, Illinois, for basic training, and were overjoyed to learn later that their request had been approved by the Navy Department.

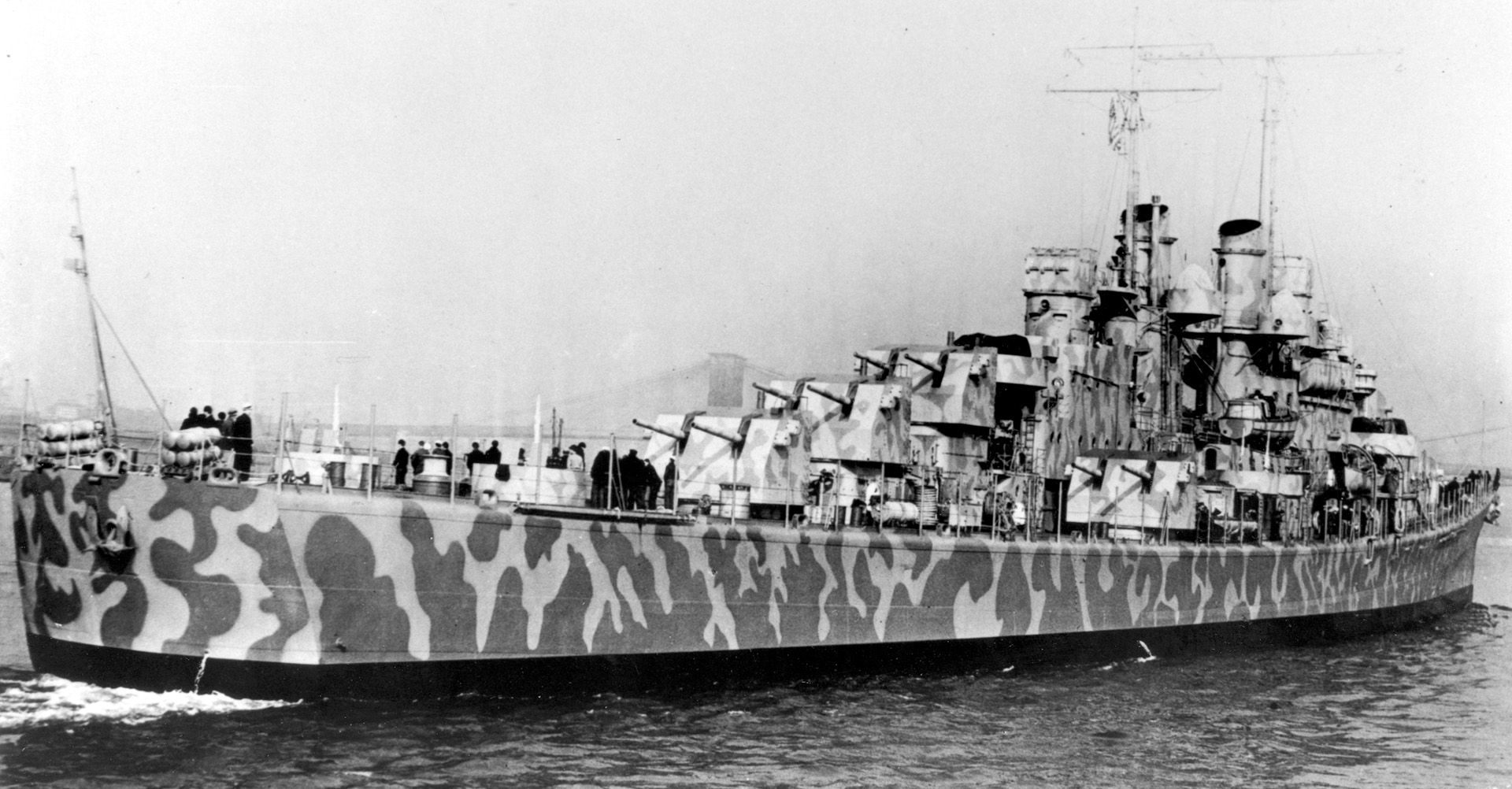

The brothers were assigned to a brand-new ship, the antiaircraft cruiser USS Juneau, and were at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on a frigid February 14, 1942, for her commissioning. The 541-foot, 6,000-ton vessel had a complement of 26 officers and 597 seamen. The Sullivans joined the crew as gunner’s mate strikers. George was a rated gunner’s mate, and Francis a coxswain.

Ordered to set course for the Pacific theater, the Juneau eased through the Panama Canal on August 17-22. The brothers wrote home that they were all together and ready to avenge Bill Ball. They always ended their letters with the words, “Keep your chin up.” Their parents watched for the mailman every day. Genevieve was living at home, and Albert’s wife, Katherine, and their baby, Jimmie, had moved into the Adams Street home when the boys left.

The Juneau’s first action came at the Battle of Santa Cruz in the Solomon Islands on October 26. She helped to screen the carrier USS Hornet in Rear Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid’s Task Force 61. The force was positioned to intercept Japanese naval units trying to approach Guadalcanal.

On November 8, 1942, the Juneau weighed anchor from New Caledonia as part of Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner’s Task Force 67, whose mission was to escort reinforcements to Guadalcanal. The Sullivan brothers saw plenty of action on November 12 during a furious attack by 30 Japanese planes. The Juneau’s gun crews accounted for six enemy torpedo bombers.

The Mission to Save Henderson Field

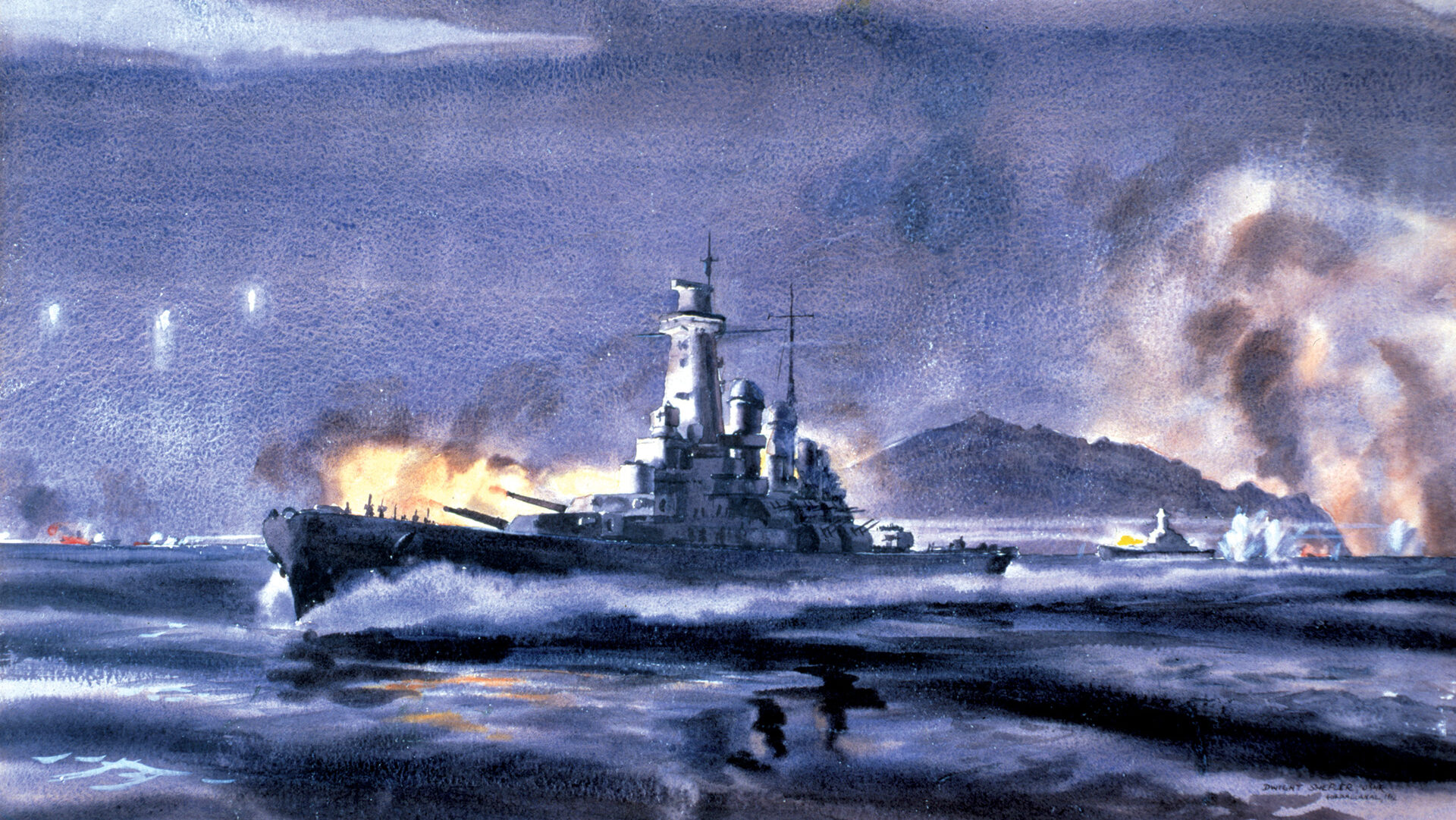

That night, the Juneau reversed course with Rear Adm. Daniel J. Callaghan’s Task Force 67.4, whose objective was to destroy a Japanese fleet steaming southward with the intention of bombarding strategic Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, which the 1st Marine Division was struggling to hold. At about midnight, the Juneau passed through Lengo Channel into “Ironbottom Sound.”

The American ships formed a snakelike column, with four destroyers in the van followed by the cruisers Atlanta, San Francisco (Callaghan’s flagship), Portland, Helena, and Juneau. Four destroyers brought up the rear

Off Savo Island at 1:30 am on November 13, the Helena reported enemy vessels on her port bow, and the opposing forces closed head on. A furious, confused battle erupted. Japanese searchlights raked the American ships as they maneuvered desperately to avoid collisions.

American salvos sank two enemy destroyers, damaged three, and damaged a battleship, but Japanese fire crippled the Atlanta and San Francisco and killed Admiral Callaghan and Rear Adm. Norman Scott. The Juneau, the last cruiser in column, loosed salvo after salvo at enemy ships on both sides—until a torpedo slammed into her forward fireroom and put her out of action. She retired with her crew struggling furiously to keep her afloat.

The American ships, unaccustomed to night fighting, took a beating but accomplished their mission to save Henderson Field. Air strikes from the field the next day sent 11 enemy troop transports to the bottom.

Torpedo Wakes in the Water

At daylight on November 13, the Juneau set course for Espíritu Santo, following the badly damaged San Francisco and escorted by four destroyers. At 10 that morning, the Juneau transferred a medical team to help tend the wounded aboard the San Francisco.

Then, at 11:01 am, as the American ships were passing 20 miles southwest of San Cristobal in the Solomons, horrified bluejackets aboard the San Francisco spotted two torpedo wakes streaking ahead of their ship, heading straight for the unsuspecting Juneau. The San Francisco’s communications had been knocked out, and there was no way to warn the other cruiser, about a thousand yards on her starboard beam. All they could do was watch the deadly white trails speed toward the Juneau.

Fired by the Japanese submarine I-26, the torpedoes found their mark. There was a tremendous explosion, and the Juneau disintegrated in a thousand-foot-tall column of flame and smoke. She disappeared below the surface in 20 seconds.

Only 10 members of her crew survived. Gone were her skipper, Captain Lyman K. Swensen, and the happy-go-lucky Irishmen from Waterloo. George, the oldest, managed to get off the ship and onto a life raft.

“The other boys were below at the time,” a Juneau survivor later told Mr. and Mrs. Sullivan. “They went down with the ship and did not suffer. It was a sad and pathetic sight to see George looking for his brothers, but all to no avail.”

The Sullivans Receive Their Telegram

Witnesses said later that George drank seawater, became delirious, swam away, and was finished off by two sharks.

The dreaded telegram from the Navy Department arrived at 98 Adams Street on January 12, 1943, and informed Tom and Alleta Sullivan that their five boys were “missing in action.” Albert’s wife, his 22-month-old son, and Genevieve shared the grief in the modest home where five white stars hung in a front window. It was the most severe loss suffered by an American family during World War II.

Yet, the remaining Sullivans braced up and tried to carry on. Tom Sullivan, at age 59, tried to hide his immense sadness as he went back on his freight runs; Albert’s wife started work at the Rath plant the day after the news came, thinking it would take her mind off the tragedy; Genevieve later enlisted in the Naval Reserve as a specialist (recruiter) third class, and the indomitable Alleta Sullivan refused to give up hope.

“All we can do now is hope,” she said. “Maybe they’ll show up somewhere, someday soon. But if they are gone, it will be some comfort to know they went together, as they wanted, and gave their lives for their country and victory.… It’s hard, of course, terribly hard. But then, I guess, if a mother has just one son and loses him, that’s just as hard. The boys always wrote at the end of their letters, ‘Keep your chin up,’ and now’s a good time to do just that.”

Telegrams and telephone calls of sympathy poured in to Tom and Alleta Sullivan from all over the country. President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a letter of condolence, offering the sympathy of the nation, and Vice President Henry A. Wallace spoke of the couple’s “marvelous spirit,” and said, “It is the spirit of the Sullivans which will enable the United Nations to gain a complete victory.”

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to Mrs. Sullivan, “You and your husband have given a lesson of great courage to the whole country, and, in thinking of this war and what it means to all mothers of the country, I shall keep the memory of your fortitude always in mind, as I hope other mothers with sons in the service will do.”

The Navy Department called the loss of the five brothers the heaviest blow suffered by a single family since Pearl Harbor, and “probably in American naval history.” It had always been policy to separate family members during wartime, and the Navy stressed for the record that the Sullivans had insisted on staying together—despite repeated objections from the Juneau’s executive officer.

Any hope that Alleta Sullivan clung to for her sons’ eventual return was shattered by a letter from a Juneau survivor, a young Nebraskan who had been a “special friend” of George’s. “I am afraid all hope is gone for your boys,” he wrote. “I don’t know whether a letter of this sort helps you or hurts. But it’s the truth. I saw it.”

The Navy Department kept the brothers on the missing-in-action list until August 6, 1943, when Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox sent the parents a letter officially listing the five as “killed in enemy action.” George, Francis, Joseph, Madison, and Albert were each posthumously awarded the Purple Heart, American defense and European-African-Middle Eastern theater ribbons, the Victory Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific theater ribbon with two battle stars. Their ship had earned five battle stars for her brief but gallant role in the Solomons naval actions.

A Household Word Across the Country

The Sullivan name was now a household word across the country, a symbol of American sacrifice and resolve in the war against fascism. Wasting no time in prolonged grief because they believed their boys would not have wanted it, Tom and Alleta Sullivan embarked on a morale-boosting tour of more than two hundred defense plants. They celebrated their 29th wedding anniversary on February 5, 1943 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, urging several thousand workers to build more war tools.

“What I feel is this, “ said Tom Sullivan. “If we had more planes and more ships out there in the Solomons, the cruiser Juneau wouldn’t have been sunk and our boys wouldn’t have been lost.” In New York, his wife told workers, “If I had any other boys, I sure would want them to join the Navy. We’ve got a little grandson. When he gets old enough, I’d like to see him join, too.” Jimmie did serve a hitch in the Navy later.

At the windswept Todd-Erie Basin in Brooklyn, Alleta Sullivan declared, “I speak as a mother who lost five sons, and they went down fighting. They were never afraid. Now we have more sons in action. We must give them everything they need.”

The couple took time out from their tour to attend a solemn Mass in New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Greeting them, Monsignor Joseph F. Flannelly said, “I have received kings and queens and premiers, but no one has been more welcome here than Mrs. Sullivan.” Archbishop Francis J. Spellman presented them with a silver religious medal that had been given to him by Pope Pius XII, and a set of rosary beads. “I know of no one else who deserves them more,” he commented. On February 8, in the cathedral’s Lady Chapel, the archbishop celebrated a Mass for the repose of the Sullivan brothers’ souls.

Later that day, Tom and Alleta went to Bridgeport, Conn., to meet Mr. and Mrs. Thomas F. Rogers, whose sons, Louis and Patrick, had also gone down with the Juneau.

Mrs. Sullivan did most of the speaking during the national tour, although she had no oratorical experience. The first time, she confessed, she was “kind of nervous.”

On February 9, 1943, the Navy Department announced that President Roosevelt had approved the naming of a new destroyer for the five brothers, and their mother was invited to be its sponsor. USS The Sullivans was to be the second Navy ship named for five brothers. The destroyer USS O’Brien, launched a few years before, commemorated Captain Jeremiah O’Brien and four of his brothers who sailed a lumber sloop out of Machias, Maine, during the American Revolution and successfully attacked a British sloop-of-war. This was the first naval engagement of the Revolution.

The Fighting Sullivans Memorial

On February 10, 1943, the Waterloo Daily Courier announced that it would sponsor a “fighting Sullivans memorial” to be erected by popular subscription.

Sunday, April 4, 1943, was a proud though tearful day for Tom and Alleta Sullivan and daughter Genevieve, now 26, as USS The Sullivans was launched at the Bethlehem Steel Co. yards in San Francisco. Alleta smashed a bottle of champagne on the bow of the trim, 376-foot destroyer, and wept. Tom squeezed his wife’s hand, and Genevieve also wept. For the three, the launching meant that the five Sullivan brothers were at sea again.

The ship was commissioned on September 30, 1943, and Commander K.M. Gentry was her skipper. When she steamed out of San Francisco Bay for the Pacific war zone, there was a member of the family aboard. Uncle Patrick Henry Sullivan, fireman first class, had joined the Navy to carry on the family name. After the commissioning, he had said, “I wish they would man the entire ship with Sullivans. We would have the hardest-fighting crew at sea.”

With a big green shamrock painted on her smokestack, The Sullivans was in the thick of the action during 18 months in the forward areas of the Pacific war. She became one of the “hot ships” of the fast carrier groups.

USS The Sullivans took part in the Marshall Islands campaign, was a leading escort in the raids on Truk and the Marianas in February 1944, fought at western New Guinea and through the Marianas and Carolines, took part in the invasions of Leyte and Luzon, and helped to land Marines on Iwo Jima. She helped to sink a Japanese cruiser in the great Battle of Leyte Gulf, her antiaircraft guns downed eight enemy planes, and her batteries destroyed five on the ground. For her efforts in tending the crippled cruisers Houston and Canberra and the destroyer Halsey Powell, she earned the title of “Good Samaritan.”

The Sullivans rescued 166 survivors from the crippled carrier USS Bunker Hill off Okinawa on May 11, 1945, and assisted in the first carrier-plane sweeps over Tokyo.

Tom and Alleta Sullivan watched the newspapers for reports about the ship, taking almost as much interest in her as they had in their sons’ service aboard the Juneau.

After distinguishing herself in the Korean War and being given the title of “Flagship of America’s Irish Fleet,” USS The Sullivans sailed with the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean in the late 1950s, and her 5-inch guns supported the initial landing of Marines in Lebanon in the summer of 1958. With 11 battle stars to her credit, she was placed in reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Base and was eventually retired to a permanent memorial berth in Buffalo, NY.

Meanwhile, Hollywood had paid tribute to the saga of the five brothers with the release by 20th Century-Fox in 1944 of The Fighting Sullivans. Directed by Lloyd Bacon and starring Thomas Mitchell and Selena Royle as the parents, supported by Anne Baxter, Ward Bond, George Offerman, Jr., and Bobby Driscoll, it was a warm, inspiring portrait of an ordinary American family that made an extraordinary sacrifice.

In Waterloo, as part of the city’s urban renewal program, a nine-acre recreation area was dedicated to the brothers on the site of the old Sullivan home. Funded by popular subscription, a pentagonal granite shrine is surrounded by a moat and anchors, and topped with a bronze shamrock from the deck of USS The Sullivans. The memorial is located a few yards east of a tree planted by the five brothers when they were children.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments