By Eric Ethier

Fresh off a tense telephone conversation with Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., climbed into a jeep and rumbled over to Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division headquarters east of Terranova, on Sicily’s northeastern coast. Dusk had fallen on August 10, 1943, and the gung-ho general with the ivory-handled pistols on his hips wanted action. Specifically, he wanted an amphibious operation scheduled for that night to go ahead as planned despite the protests of his subordinates.

“Goddamit, Lucian,” Patton roared, “what’s the matter with you? Are you afraid to fight?” Truscott brushed off his boss’s challenge. “You have ordered the operation and it is now loading. If you don’t think I can carry out orders, you can give the division to anyone you please.”

The problem, Truscott insisted, lay in linking his advancing infantry with the landing force before regrouping German defenders shoved them into the sea. But Patton would not be moved.

A month into Operation Husky, the Allied campaign for Sicily, Patton was pushing his Seventh Army hard in an effort to seal the Axis escape route at Messina. While the 9th Division pressed the 15th Panzergrenadier Division northwest of towering Mount Etna, to the south Truscott’s 3rd Division was driving the 29th Panzergrenadier Division eastward from the ridges along coastal Highway 113 and the Tyrrhenian Sea. South of Etna, meanwhile, Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army was hurtling toward Messina up the island’s mine-strewn southeastern coast. Keen to bag German prisoners and equipment, Patton was equally eager to outpace Montgomery and earn some accolades for his young army.

But Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s Axis legions (by early August, mostly Germans under the direction of General Hans Hube) were moving grudgingly. Forced from the formidable Etna Line on August 5, the 29th Panzergrenadier Division withdrew behind blown bridges to new positions along the San Fratello Ridge. With the help of Admiral Lyal A. Davidson’s Task Force 88 transports, Lt. Col. Lyle Bernard’s 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry, leapfrogged the German position by sea on August 7-8, gaining 12 miles in a hair-raising raid.

Hoping for still better results, Patton ordered another amphibious operation for the night of August 9-10. Designed to skirt the new German defensive positions along the Naso Ridge, on the Cape Orlando-Randazzo line, this one would place American GIs just west of the town of Brolo. With luck, the balance of Truscott’s onrushing 3rd Division would roll up a tidy bag of German prisoners. But after allowing one postponement caused by a damaged LST (landing ship, tank), Patton was in no mood to heed the last-minute requests of Truscott and Maj. Gen. Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. II Corps, for another.

Once again, the job fell to the 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry, a gritty bunch that reflected the spirit of its commander. Closer in appearance to a college professor than a typical infantry leader (he was destined for a post-Army career teaching mathematics), Lyle W. Bernard was spectacularly lean and sported a wisp of a moustache on his long face. Just 33, this thoughtful Idaho native habitually chewed on a pipe and referred to himself as “the Old Goat.” But he had also entered West Point from the soldiers’ ranks and was a smart, tough, and cool customer.

Bernard’s understrength command included perhaps 650 men, his weary 2nd Battalion backed by five medium tanks from the 756th Tank Battalion, eight self-propelled guns from the 58th Armored Field Artillery, and engineers from the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion and the 540th Amphibious Engineer Regiment. Tagging along to watch was an impressive squad of press men led by veteran battlefield scribes Jack Belden (Time and Life), Don Whitehead (Associated Press), and Homer Bigart (New York Herald Tribune). Each watched as Bernard spoke to assault troops gathered atop his LST before they climbed down into their assault boats.

“I didn’t want to make this operation,” he declared. “I didn’t think I had enough men, enough tanks, or enough time. And I, like you, am tired.” Noting the reassuring presence of three coast-hugging destroyers and the light cruiser USS Philadelphia, he added, “If we catch that bastard this time, we’ll be in Messina within a week.”

Bernard’s target was Monte Cipolla, the double-humped nose of a ridge that petered out 450 yards short of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Commanding both the coastal road and the stone-housed village of Brolo, just to the east, it was held by only the tiny headquarters force of Colonel Fritz Polack’s 29th Artillery Regiment, the balance of which was posted alongside portions of the 71st Panzergrenadier Regiment in and beyond Brolo.

After staking out a beachhead between the dry Brolo and Naso riverbeds that flanked Monte Cipolla, Bernard would cross Highway 113 and occupy it with two companies. But he expected quick and heavy counterattacks and was counting on assistance from the 7th and 15th Infantry Regiments backed by the 30th Infantry’s two remaining battalions which would quickly fight through General Walter Fries’s 29th Panzergrenadier Division (the 71st and 15th Panzergrenadier Regiments) and across the rugged Naso Ridge.

Under a star-filled sky and the protective guns of the Philadelphia and six destroyers, landing craft lugged Task Force Bernard ashore between 2:43 and 3:30 am on August 11. Slowed only by barbed wire, Company E split up to secure the landing site’s flanks, bridges over the Brolo River to the east and the Naso River to the west. While engineers struggled to wheel the armor and field artillery into position, Companies F and G, fortified with the heavy machine guns and 81mm mortars of Company H and trailed by Bernard and his battalion headquarters, dashed inland.

In the quiet, predawn darkness, the extended line crept over a massive railroad embankment, through a large lemon grove, and over a high stone wall to cross Highway 113. Crouching low, the troops let an oblivious motorcyclist pass. Then came the ominous rattling clunk of metal on pavement.

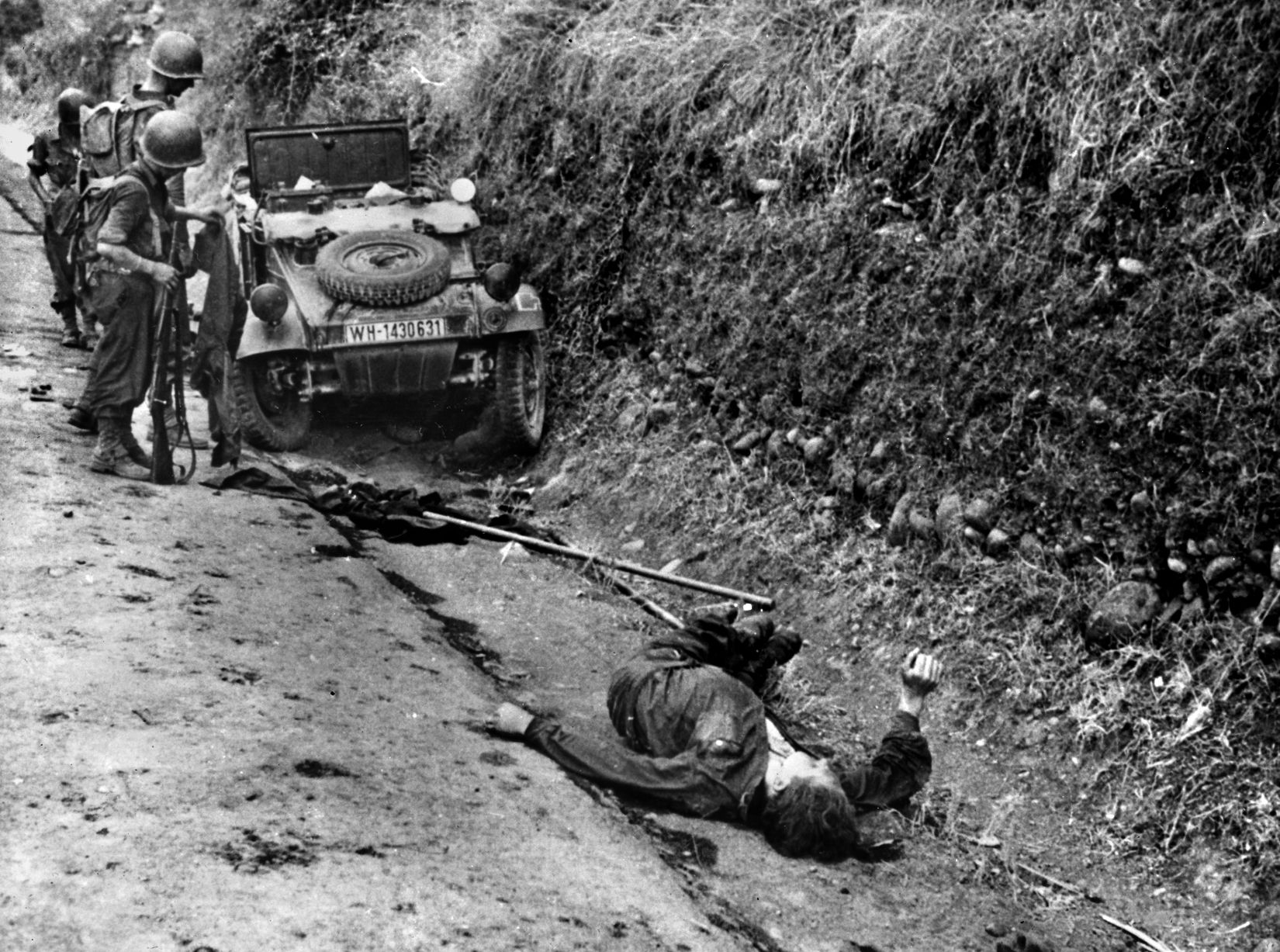

“We dived behind a stone wall,” newsman Bigart recalled, “waiting for what seemed an eternity. The clanking grew steadily louder and finally materialized as a German half-track.” The lumbering vehicle slowed, and nervy Americans blasted its driver with rifle fire. When a German officer stopped to investigate moments later, a GI blasted his car with a bazooka.

“By this time,” Bigart noted, “the Germans in Brolo were thoroughly awake.”

Surprised Germans posted around Brolo fired off flares and opened fire as Bernard’s men struggled up the nose of Monte Cipolla, a treacherously steep, brick-hard height topped by scrub trees and Colonel Polack’s headquarters outfit. Polack’s outgunned party tore up the slopes around the scrambling Americans with small-arms fire, killing several, then beat a hasty retreat off the hill and into Brolo.

Trading their rifles for shovels, the Americans went to work digging slit trenches and setting up mortar positions with Company F on the first hump and G slightly behind and to its left. Others assigned the labor to a group of German soldiers found napping in a ditch, apparently unfazed by the fire. By the time Philadelphia began delivering supporting fire at 5:38, Monte Cipolla was secure.

Caught off guard by the American landing, General Fries ordered Polack to organize an attack on Bernard’s fragile, 2,000-foot-wide beachhead while he dispatched help from the west. He got further help from the terrain as gaping gullies and monstrous stone walls soon immobilized each of Bernard’s five M4 Sherman tanks, rendering them all but useless. Bernard’s 105mm self-propelled guns had no better luck maneuvering into the terraced rise below the highway, and their crews set up shop in the lemon grove below.

As the sun climbed into a cloudless sky above Bernard’s hilltop stronghold, German scouting parties crept down the Ficarra Road and dusty bed of the Brolo River to the southeast. Company G fire shattered both. Spotting a company of 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment reserves along the dusty bed of the Naso River to the west, Bernard’s GIs greeted them with rattling machine guns and thumping mortars. The attackers retreated minus 30 of their comrades.

Then, at about 9 am, a procession of trucks carrying 71st Panzergrenadier infantrymen rumbled down Highway 113 from Cape Orlando. From the deck of the Philadelphia, the procession resembled a bumbling line of ducks in a huge shooting gallery. Together with Bernard’s seaside artillery, her six-inch guns plastered the twisting highway and sent numbed German infantrymen diving for cover.

By late morning, however, Bernard was beginning to worry. Provided with air cover only until noon, the Philadelphia and her destroyer escort steamed west for the safer waters off Palermo. Germans mowed down the Americans’ ammunition-carrying mules in their hillside tracks, squeezing off Bernard’s supply line from his parked DUKWs (amphibious vehicles better known as “Ducks”) and forcing his mortar crews to ration rounds.

Grass fires sparked by exploding shells sizzled across Monte Cipolla, burning up telephone wires and cutting off thirsty GIs from the height’s only stream. Still more difficulty was forthcoming. Pressed by Truscott’s advancing infantry, Lt. Col. Walter Kreuger was marshaling his 71st Panzergrenadier troops for another push down the coast. Shortly after 11 am, Polack packed two companies of infantry into personnel carriers, backed them with a half dozen tanks, and sent them rumbling out of Brolo. From his lonely olive grove headquarters atop Monte Cipolla, Bernard watched as the Axis pincers closed on his command.

For help, Bernard could only appeal to Truscott, who was anxiously monitoring developments from his command post. Beginning at 11:40 Bernard called for air, naval, and finally artillery support; Truscott responded by turning loose his 155mm Long Tom artillery on Brolo, and relaying appeals upward to Patton.

Reporting Polack’s advance at 12:30, Bernard radioed: “Must have everything.” As minutes passed and substantial aid failed to materialize, his appeals became increasingly desperate. At 1:05, Bernard reported, “Situation critical.” At 1:40, he radioed, “Enemy counterattacking fiercely. Do something.”

Some help arrived in the form of the returning Philadelphia, whose guns began booming again at 2:04 pm. While the cruiser’s shells chewed up the coast, a dozen A-36 fighter-bombers, the ground attack version of the North American P-51 Mustang fighter, arrived to blitz Brolo. A second group followed a half hour later. But the effective one-two, sea-air punch quickly fizzled. Stymied by a loss of radio contact and convinced the ground situation was in hand, Admiral Lyal Davidson pulled the Philadelphia away from the coast once more.

Jumping at his sudden advantage, Krueger unleashed his artillery on Bernard’s fragile beachhead while three tanks smashed across Bernard’s Brolo River flank. Closing quickly on Battery B’s howitzers, Polack’s tankers quickly destroyed two; a third American crew then confronted a German tank in a point-blank duel that left each vehicle in flames. Wheeling in support, a Battery A gun holed a second tank and sent the third rolling back to the cover of town after pausing to blast Battery B’s remaining gun.

Monitoring the shoreline contest from smoke-draped Monte Cipolla, Bernard showed little anxiety. Don Whitehead recalled that he was “puffing at his dead pipe as though this were a Sunday afternoon picnic and he was enjoying the antics of a playful group of children.”

To firm up his flanks, Bernard sent Company F scrambling downhill to the vital Brolo overpass to relieve besieged Company E riflemen, who, in turn, trekked west to join their company mates at the Naso bridge. Then tragedy struck. Racing to Bernard’s aid just after 4 pm, the A-36s misplaced their payloads. Exploding bombs killed 19 Americans and wrecked all four of Battery A’s 105mm guns. Bernard calculated his options and chose to consolidate, ordering all units to join him on the heights of Monte Cipolla.

“We are now preparing to make one of Bernard’s last stands,” he told one officer. “We will go into a tight circle on the hill and defend ourselves with rifles.”

Heeding urgent Seventh Army calls, the hard-working Philadelphia appeared yet again to blast German targets. Opening up at 4:31, the cruiser quickly drew the guns of buzzing Focke Wulf Fw-190 fighters.

Then, another quirk of misfortune all but sealed Bernard’s fate. Hitching a ride out to the cruiser to reestablish broken communications, a fire control officer inadvertently spurred a confused exodus of Ducks. American fighters arrived to cover the strange retreat, but Bernard’s badly needed ammo was lost. By 5:25 pm, his situation was dire: “Must have navy and air on 702504 (coordinates) immediately or we are lost,” Bernard’s aide radioed Truscott. Lacking air cover, the Philadelphia steamed westward at 6:25, this time for good.

Darkness and fog descended on Monte Cipolla as Companies E and F scrambled for the hilltop retreat. Thwarted by shadowy terrain and German fire, GIs clung in pockets to the flats below the ridge top. Those who reached the summit extended Bernard’s thin line and defended it with grenades and machine-gun fire. Tracers zipped across the dark landscape like neatly organized fireflies.

Jack Belden testified that enemy bullets smacked “against the hard ground and churned into confusion the hill, which swarmed with figures running and cursing and falling down.” During lulls in the action, German chatter flitted up from the highway; enemy footfalls sounded in the surrounding hills. Come daylight, Bernard told his diehards that they should be ready to slip from their trenches and try to reach Truscott’s lines.

At the last moment, lady luck finally smiled on Bernard. A day earlier, General Hube had implemented full-scale German evacuation plans, and Fries’s 29th Panzergrenadier Division had received orders to withdraw eastward with all haste. Turning from the pesky force atop Monte Cipolla, German troops began piling into trucks and rumbling east down shell-blasted Highway 113. Truscott’s 3rd Division, meanwhile, had surged up the coast, across Naso Ridge, and into Bernard’s backyard. At 1:30 on August 12, 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry troops made contact with the 2nd Battalion.

“Then,” said Sergeant Jack Dailey, “we came down off the hill. But a lot of guys didn’t.”

Of Bernard’s 650 men, 177 were casualties; at least 40 were dead. Greeting a relieved General Truscott that morning, Bernard said, “General, you just don’t know how glad I am to see you.”

Arriving later that morning to view charred bodies strewn across the surf, Patton crowed about the battalion’s accomplishment. Some of the newsmen were not in the mood. “All at once,” Whitehead wrote, “the whole little tableau sickened me.”

Had the ships been available to support it, a larger assault force likely would have trapped much of the 29th Panzergrenadier Division. As it was, only Bernard’s grit, sharp gunnery from the Philadelphia, and Hube’s withdrawal orders had prevented what might have been the task force’s annihilation. By the time Patton buttoned up Messina on August 17, barges had ferried some 40,000 German soldiers and 10,000 vehicles across the Strait of Messina to the Italian mainland.

Author Eric Ethier writes from his home in Narragansett, Rhode Island.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments