By Eric Niderost

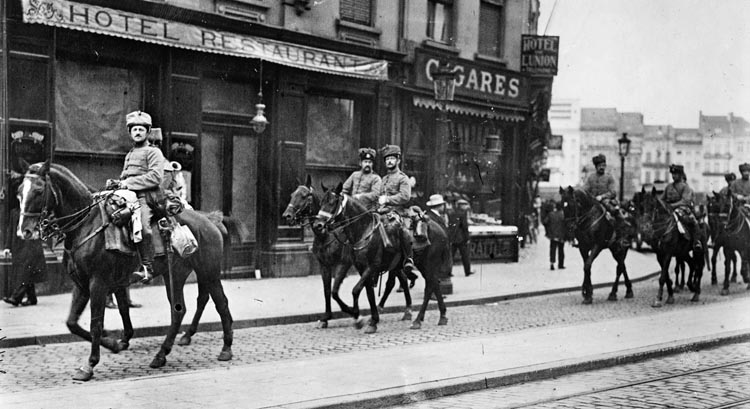

Joseph Mary Nagle Jefferies, a correspondent for Britain’s Daily Mail, was assigned to cover the opening phases of World War I in Belgium in October 1914. One day in early October and decades before Winston Churchill was to become Prime Minister of Great Britain, Jeffries was standing on the Lier Road, not far from the city proper. As the minutes passed, the scene quickly dissolved into chaos. Jeffries was at a crossroads, but he did not know the exact location. The commotion and confusion were so great that he had lost his bearings.

Tensions ran high among the soldiers and civilians in whose company Jeffries found himself. This was because monstrous German artillery guns that could maim and kill with horrifying ease might start a terrifying barrage at any moment. A traffic jam of immense proportions developed at the crossroads.

“The jamming of vehicles to and from the front, rearing of horses and shouts, ambulances involved with ammunition wagons, cars all honking and screaming at each other, [and there was] no one to direct, no one to disentangle the jumble, which grew worse every minute,” wrote Jefferies.

Seemingly out of nowhere, a man jumped out of a car and began directing traffic with unusual verve and surprising skill. He climbed atop what appeared to be a platform, although Jefferies could not see exactly what he was standing on. The platform raised the man slightly above the seething mass of animals, vehicles, and men. The red-haired, slightly balding man was flamboyantly dressed in a “flowing dark blue cloak [with] silver lion-head clasps,” Jeffries wrote. The man’s stint as a traffic guard was a virtuoso performance, with precise movements and sharp gesticulations that he punctuated with loud commands given in a crazy mixture of English and French.

Jefferies watched in awe as the stranger’s efforts actually helped the traffic flow and ended the chaos. But the most remarkable thing about the man was his identity. He was none other than Winston Spencer Churchill, Great Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty. The ministerial civilian position was the Royal Navy’s political head, appointed by the ruling party.

Why Winston Churchill Was Stationed in Belgium During World War I

It was highly unusual for an Englishman to be directing foreign traffic in the middle of a war, but even more unusual for the First Lord of the Admiralty to be in Belgium. Winston Churchill was on a mission that, if successful, might rescue Antwerp from the clutches of the Germans. At the very least, a successful defense of Antwerp would buy time and prevent the Germans from pushing on and taking the Channel ports, Great Britain’s gateway to Europe and a vital link to its ally, France.

Churchill was in Belgium to assess the situation and persuade the wavering Belgian government that London had both the will and the means to keep Antwerp out of German hands. His French was serviceable but far from perfect. Could he talk the Belgians into continuing their stout-hearted defense of Antwerp?

Antwerp’s crisis had its roots in the outbreak of the war, a scant two months earlier. Germany, faced with the prospect of a two-front war, thought it had the solution in a modified Schlieffen Plan. The first step was to fight a holding action against the Russians in the East. The Russian steamroller was a lumbering giant, ponderous and slow, and would take time to mobilize fully. While the Russian bear tried to wake from its peacetime hibernation, the Germans intended to knock France, and perhaps even Britain, out of the war.

The Germans planned to lure French armies into the disputed Alsace-Lorraine region of northeastern France, and if the French took the bait, the second phase of the operation would commence. The German First and Second Armies, massing on the Belgian and Luxembourg borders, would suddenly spring forward in a wide, sweeping arc, a great enveloping movement that would continue into northern France and get behind the unsuspecting French armies. If executed well, this right hook would also take Paris in the bargain.

To perform this maneuver, however, German troops had needed to march through Belgium, whose neutrality had been guaranteed by the Allied powers. Belgium prided itself on its strict adherence to neutrality principles but was far from naive when it came to the exigencies of European power politics. A minnow surrounded by predatory sharks, Belgium knew its small field army could never fend off an invasion from one of the European great powers such as France or, after its unification in 1871, a militaristic Germany.

Belgium had won admirers from around the globe for its heroic, month-long stand against the German juggernaut following Germany’s invasion of the country in August 1914. The stubborn resistance of its small army had bought precious time for the French and British to marshal their forces and achieve victory at the Marne River in September.

Although Franco-British forces had checked the German onslaught at the Marne, the Germans still seemed to have momentum enough to turn defeat into ultimate victory. Antwerp, which was situated on the lower Scheldt River, was Belgium’s great commercial emporium, a major seaport, and a mighty fortress.

The German Army’s mop-up operations in October included the reduction of Antwerp, which the Germans invested on September 28. Jefferies was on hand to witness what seemed to be the death throes of Belgian independence.

Antwerp’s strategic importance had been recognized for centuries. The Spanish had erected a bastion wall around the city in the 16th century, and other works were built as the years went on. But the port city’s real life as a fortress began in the late 1850s, nearly 30 years after Belgium’s independence. Belgian planners recognized the country had few viable options. The national territory was only about 150 miles east to west and 100 miles north to south, so a system was developed that divided Belgium into fortified zones. The Belgian Army, too small to fend off a major invasion in the field, would use the rivers and a series of fortresses to slow enemy progress until help arrived. Sooner or later, one or more of the Allied powers would come forward to rescue the tiny nation.

As plans developed, the idea of a National Redoubt became firmly lodged into the Belgian national consciousness. Antwerp was designated to become an impregnable fortress where the government and army could find refuge in time of war. The Belgians began constructing a series of eight forts in 1859 along the southern flank of the city. The works, which were numbered One to Eight, were situated between the outskirts of Wijnegem and Hoboken.

But that was not all. Fort van Merksem was erected on the right bank of the Scheldt facing the Netherlands and Germany, and on the left bank, Forts Kruibeke, Zwijnddrecht, and St. Marie were intended to protect the city from a coastal attack from France or Great Britain. In the murky, ever-changing world of European power politics, it was better to hedge your bets as to who would ultimately be your friend or foe.

General Henri-Alexis Brialmont was taking no chances. A brilliant military engineer, he was nicknamed the Belgian Vauban for his talented designs. But forts One though Eight and the other posts generally had been built between 1861 and 1871, a time of rapid advancement in artillery and fort construction. By 1880, even the newest of these were approaching obsolescence. They were mainly made of brick, serviceable enough to withstand the artillery of the 1850s but woefully inadequate against the heavier guns being developed in the latter half of the 19th century.

An Ambitious Plan for a National Redoubt

Recognizing this, an ambitious plan envisioned a new defensive ring of concrete fortresses that would be situated just forward of the natural borders formed by the Rupel and Nethe Rivers, between Lierre and the lower loop of the Scheldt. This new ring would feature fortresses of the very latest design, with reinforced concrete and revolving steel turrets. These steel cupolas were designed to absorb the pounding of 21cm siege guns.

The majority of the forts were to be polygon-shaped. Each had a water moat and a spannning bridge. The steel turrets boasted 15cm, 12cm, and 7.5cm guns, all capable of dealing out considerable punishment. The approaches to the forts were defended by 5.7cm rapid-fire guns, also encased in steel turrets. Forward observation posts, each of which was sheathed in concrete, would give excellent target information to fort guns, the data communicated through a series of telephones.

Unfortunately, politics and budget restrictions got in the way of construction goals. There were the usual bureaucratic squabbles, and it was not until 1906 that construction on the new ring of forts began in earnest.

By 1914 much had been accomplished, but the so-called National Redoubt was still incomplete and riddled with flaws. To save money, some older-model cannons were emplaced. These weapons used old-fashioned gunpowder, whose telltale smoke gave away an artillery position. There were gaps in the telephone lines, some turrets did not yet have guns, and concrete had not been poured in some places.

This is not to say that the defenses of Antwerp were not strong, for even with these critical flaws the forts had enough firepower to give an enemy pause. The 65,000 fortress troops were taken from the oldest classes of Belgian troops, undertrained and often poorly supplied, but they were stubborn defenders of their native soil. Antwerp would be a hard nut to crack.

The National Redoubt, however, had a secret, hidden flaw that was not readily apparent: improvements in artillery were fast rendering forts like the ones that ringed Antwerp seriously compromised, even obsolete. In the years preceding World War I, the Germans were preoccupied with the looming threat of a two-front war, one that involved the French and possibly British in the West and the Russians in the East. More importantly, they knew that their potential enemies had powerful fortresses that might impede the German Army. Worse still, the fortresses might actually stop the German juggernaut in its tracks.

There was nothing for the Germans to do about this other than develop more powerful guns, which they did in earnest. The Germans to secretly began to develop massive howitzers and mortars, artillery that could overcome the modern French, Russian, and Belgian fortifications. Undoubtedly the most famous of these, at least in retrospect, was the Big Bertha 42cm siege howitzer. It could fire projectiles up to 1,785 pounds about six miles. One type of shell fired by this behemoth was a delayed-action type that detonated after the projectile had penetrated up to 40 feet of concrete and earth.

These super weapons were first unveiled in the opening days of the war, and they caught the Allies completely by surprise. The first obstacle the Germans encountered in their invasion of Belgium was the fortress of Liege. General Gerard Mattieu Leman was the Belgian commander at Liege, tough, courageous, and stubborn, and his men followed his example. The Liege forts had to be literally pounded into submission, and one by one they were smashed into heaps of concrete rubble and twisted metal.

Liege had fallen, but its sacrifice had not been in vain. The Germans had suffered more than 42,000 casualties and, most importantly, they had lost precious time. The unforeseen delays gave the French and British time to gather their forces and plan a suitable riposte to the German thrust. But it was clear that in the short term the badly outnumbered Belgians could do little to stop the field-gray avalanche. It looked like the main Belgian Army might be enveloped, cut off from Antwerp, and compelled to surrender.

To prevent this, Belgian King Albert I ordered a withdrawal: The king, Belgian government, and the main field army fell back to Antwerp, making it the new epicenter of national resistance to the invader. Brussels fell to the Germans on August 20. The Germans were in a hurry and desperate to make up for lost time, so they bypassed Antwerp and continued west. The invaders felt that the Belgian Field Army was a spent force, bottled up in its fortress city and no longer any appreciable threat to Teutonic plans.

As August turned to September, German armies met both the French under General Joseph Jacques Cesair Joffre and the British Expeditionary Force under General Sir John French. The armies fought a series of clashes known as the Battle of the Frontiers. The Germans swept into northern France, only to received their celebrated check at the Battle of the Marne, which raged from September 6 to September 12.

Deguise’s Two Sorties

General Victor Deguise was appointed commander of Fortress Antwerp, the National Redoubt. He had control of both the Field Army and the troops manning the forts that ringed the city. In the early, uncertain days of late August, when the situation was in flux and the French seemed on the edge of defeat, King Albert was determined to help his Gallic allies as best he could. A popular and resolute monarch, Albert was keen on offensive operations, so he ordered Deguise to mount a sortie from the city. The general responded with alacrity.

The first sortie took place on August 25 against the German III Reserve Corps between Wolvertem and Aarschot. The Germans, whose overconfidence bordered on arrogance, had only a thin screen of troops watching the city. Taken by surprise, the Germans were driven back several miles before they could mount an effective defense. When King Albert received a message from General Joffre that a general retreat was in effect, the monarch ordered the four Belgian divisions taking part to disengage and fall back to the outer fortress line.

The sortie had proved useful, distracting the Germans and spreading consternation in the rear areas. On the evening of August 25, when Belgian troops were still returning from their sortie, Antwerp experienced another new and terrifying aspect of modern war: the air raid. The German zeppelin Sachsen, commanded by Captain Ernst Lehmann, dropped seven or eight small bombs on the city. It was entirely random and literally hit or miss; one bomb landed in a park, another landed in an empty street. At least two houses were destroyed. The bombing run killed 10 people and wounded another 15.

Lehmann cut the motors when he glided over the city and made sure the moon had set—a necessary precaution because the weight of the bomb load was such Sachsen was only a little more than 5,000 feet in altitude, well within range of ground fire. It was said that one of the bombs fell near where the king and the royal family were staying, but they emerged unscathed. Lehmann became a celebrated airship officer who was fated to die on the Hindenburg in 1937.

Another sortie on September 9 achieved mixed results. Belgian cavalry units chased the Germans out of Aarschot and bagged 350 prisoners in the bargain. But once again the Belgian offensive ran out of steam, partly because its infantry attacks had been halted by powerful German artillery. There was also a third, somewhat abortive, sortie later on.

Antwerp was rapidly becoming a thorn in the German side, a troublesome presence on their right flank and rear. The Germans resolved to eliminate this pocket of Belgian resistance, so a German siege corps of 125,000 men was tasked with capturing the city. General Hans Hartwig von Beseler commanded the force. It was composed of the III Reserve Corps, IV Ersatz Division, one division of Marine Rifles from Marine-Korps-Flandern, and one Bavarian division. Rounding out the force were the 26th and 27th Landwehr Brigades, one brigade of siege engineers, one brigade of light artillery, and nine powerful heavy siege mortar batteries.

The Tricks of the Belgians and the German Advance

The formal siege opened on Sunday, September 27, with an attack by the 5th and 6th Reserve Divisions advancing between Dijle and Nete. They were opposed by the Belgian 1st and 2nd Divisions, which fought bravely but were forced back by superior German artillery fire. The Germans then committed an atrocity, one of many that outraged world opinion. The small town of Mechelen was about two miles from the nearest Belgian fort, with no intrinsic military or strategic value, but was shattered by German shells. The civilian population in Mechelen was given no advance warning, so many died in the ruins of their city.

The Belgians still had a few tricks up their sleeve, however. At one point, one of the forts was seen to erupt in sheets of orange-yellow flame. Encouraged, the Germans rose up and launched an infantry assault to capture the prize only to find that it was all a ruse. As the gray-clad troops surged forward, they were met with devastating machine-gun and rifle fire from the fort support trenches. A Teutonic brigade was cut to pieces, its ranks thinned by the hail of bullets, and the survivors found their escape barred by an electrified barbed-wire fence.

At least two German batteries and several other infantry battalions were also fooled by similar tricks; there seemed to be no limit to Belgian ingenuity. But the next day the tables were turned, and the fate of Antwerp was in the balance. The primary German targets were Forts Waelhem and Wavre St. Catherine, two of the main posts in the city’s outer defense line. It was time for the super heavy guns to make their Antwerp siege debut. Massive 30.5cm and 42cm Big Bertha artillery were emplaced at Boortmeerbeek, about 10 miles south of the fortress line, a distance that constituted their maximum range. These positions were well out of the range of the Belgian fortress guns, so the dangers of counterbattery were negligible.

The bombardment began around noon. The two fortresses became living hells as the huge shells rained down. Concrete cracked and split under the ceaseless pummeling. The bombardment was intense, the projectiles coming down at the rate of 10 shells per minute. Each ear-splitting detonation was accompanied by gouts of acrid smoke and flame. Some of the explosion fumes seeped down into the fort interiors through the shattered concrete, filling the passageways with the stench of cordite.

General Gerard Leman, the heroic commander of Liege, described what it was like to experience this shelling when he endured it earlier in the campaign.“We heard them coming,” he said of the one-ton shells. “We heard them howling through the air, and finally the noise of a furious hurricane, which ended in a terrific thunderclap, and then clouds of dust and smoke above the trembling ground.”

The forts still held and returned fire as best they could. Shells from their 15cm guns rained down on German infantry positions. Nevertheless, the Belgian forts simply could not stand up to the punishment they were receiving from the Teutonic 42cm and 30cm mortars.

Fort Waelhem was a wreck, even though most of its guns remained in action. Only one 15cm gun turret had been destroyed, so the garrison stayed on, inspired by its commandant. He initially ordered an evacuation of the fort but some troops apparently stayed on with him. The Germans automatically assumed that Fort Waelhem would be abandoned. A patrol was sent forward to scout the position only to discover the garrison was very much alive and ready to do battle. Heavy Belgian fire forced the German patrol to scamper for cover.

But the Germans persevered, and one by one the forts were captured. This continued until all the forts south of the Nethe River were in German hands.

Nothing, it seemed, could stop the inexorable German advance. On October 2 the Belgian Supreme Council on National Defense, which was presided over by King Albert, gathered to determine a future course of action. After much deliberation it was decided that the king and his family, the Belgian government, and the Field Army would evacuate Antwerp the next day. The citizens of Antwerp were told as much in a royal proclamation. It was a tough decision, but there seemed to be little alternative. It was imperative that none of these important national figures or entities fall into the hands of the Germans.

Churchill Gets His Orders. Can He Convince the Belgians to Hold On?

Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener, Great Britain’s secretary of state for war, was not pleased when he heard the news. In fact, he was appalled. Kitchener’s main concern was the Channel ports, such as Calais, Ostend, and Dunkirk. They were the vital links that connected Great Britain to its French ally, where men, equipment, and supplies could reach the Continent. More importantly, at least in Kitchener’s eyes, if the Germans occupied the Channel ports they might use them as springboards to invade Britain itself.

Kitchener’s fears were not entirely unfounded and were backed up by history. It had been a cornerstone of British foreign policy not to allow any hostile powers to control the Low Countries or any regions bordering the North Sea or English Channel; if they did, as during the time of Louis XIV or Napoleon, British policy was to oppose them.

Prime Minister Herbert Asquith was out of town, so Kitchener asked Foreign Secretary Edward Grey to come to his home in Carlton Gardens, London, to discuss the situation. When he discovered Winst0n Churchill was on a train bound for Dover, Kitchener had the train stop, reverse direction, and return to Victoria Station. When the train pulled into the station, Churchill piled into a waiting car that drove him to Carlton Gardens.

Apprised of the situation, Churchill responded with alacrity. There were no regular troops available, so he suggested his newly formed Royal Naval Division be sent as a temporary stopgap measure. In addition, there was a force in France that could be dispatched immediately: A Royal Marine Brigade, 2,000 men with some Oxfordshire Yeomanry, was already posted in Dunkirk. This force also included armored cars and some Royal Naval Air Service airplanes under Commander Charles Rumney Samson. The Royal Navy Division, still in England, would join them one or two days later.

Churchill’s main mission was to assess the situation in Antwerp, as well as to also use his considerable powers of persuasion to try and get the Belgians to hold the city for a few more critical days. The First Lord of the Admiralty was to assure the Belgians that help was on the way in the form of the 2,000 Royal Marines and 8,000 men of the Royal Naval Division. Moreover, he was to inform them this was just the beginning of the reinforcements they could expect. A new British Army division, the 7th Division, was forming under General Henry Rawlinson and would arrive within 10 days. The French also offered support in the form of the 87th Territorial Division and the Brigade de Fusiliers Marins.

Churchill possessed a fertile imagination, boundless energy, and a restless ambition that always sought new paths to advancement. He was capable of real brilliance, of thinking outside the box, and was always fascinated with innovation, including airplanes. He formed a naval aviation branch in 1912 called the Royal Naval Air Service. Such traits, although often admirable, made him seem to his more conservatively inclined colleagues to be a glory hound at best and a near- madman at worst.

His Royal Naval Division had reservist brigades named for the most part after famous English admirals, such as Francis Drake, Edward Hawke, and Horatio Nelson.

These reservist brigades comprised both experienced mariners and raw recruits. The “old salts” resented the fact that they would be used as land soldiers and would not be going to sea again. Churchill specifically stated that raw recruits should not be sent to Antwerp. But, whether by intention or by design, that is precisely where they were sent.

Churchill arrived in Antwerp on October 3. When his car roared up to Antwerp’s Hotel de Ville, which served as city hall, one wag said it was like a “melodrama where the brave hero dashes up bare headed on a foam-flecked horse.”

The First Lord of the Admiralty was dressed in the uniform of an Elder Brother of Trinity House, Britain’s lighthouse service—a getup that included a pea jacket and visored naval cap. It looked unusual, so a Belgian official asked what this outfit meant.

A “Brother of the Trinity”: How Churchill Won Over King Albert and Prime Minister Broqueville

Churchill, using his slightly lisping French, was eager to reply. “Moi, je suis un frere aine de la Trinity,” he proudly responded. “I am an elder brother of the Trinity.” The Belgian, who thought that Churchill was saying that he was divine, was astounded. “Mon Dieu!” he exclaimed. “La Trinite?”

Heartened by Churchill’s words and his optimistic tone, King Albert and the thickly mustachioed Belgian Prime Minister Charles Broqueville agreed to hold out for six more days, and maybe even 10 days if fortune favored the Belgian cause. There was one caveat to this agreement: if the Germans were on the verge of taking the city, the Belgian Field Army would withdraw, escaping to fight another day. Some elements of the Belgian Field Army, including the new recruits, were already withdrawing. All parties agreed to these arrangements.

Always eager for action, Churchill visited the front again the next morning, this time observing a sector near Lierre occupied by his own Royal Marines. “German soldiers were creeping from house to house or darting across the street,” recalled Churchill. But as evening arrived and the scene grew dark, such visual observations were replaced by auditory ones. There was the dull crack of rifles and the staccato chatter of machine guns, including a Royal Marine machine gun on a balcony. “Streams of flame pulsating from the mouth of machine guns lit up a warlike scene amid crashing reverberations and the whistle of bullets,” Churchill wrote.

Churchill’s boyish enthusiasm could not be suppressed. He directed troops, sat atop guns, and bombarded London with cable messages asking for entrenching tools, field telephone sets, high-explosive shells, and Maxim machine guns and ammunition.

General Rawlinson was supposed to arrive in Antwerp in advance of his 7th Division, but he was delayed. Nature abhors a vacuum, and Churchill suddenly saw an opportunity to take real command. He wired Prime Minister Asquith that in light of the situation he was willing to resign as First Lord of the Admiralty and literally take command of the forces now at Antwerp, both the defensive troops on hand and the relieving troops en route.

Asquith read the telegram with a mixture of amazement and horror. Churchill had seen active service in India, Sudan, and South Africa, but only as a junior officer. At the outbreak of the war, he was nothing more than a civilian and a cabinet minister. Asquith read Churchill’s message aloud to the cabinet, which responded with gales of laughter. Many in the government disliked Churchill. His detractors considered him to be stark-raving mad.

Asquith responded negatively to Churchill’s requests, but oddly enough, Kitchener, who was no friend of Churchill’s, actually thought the idea had merit. Surprisingly, Kitchener was fully prepared to welcome Churchill back into the Army with the rank of lieutenant general. But Asquith stood firm on the matter. Winston was to return to England and resume his duties as First Sea Lord.

The Germans Finally Cross the River: An Antwerp Invasion Was Imminent

The rapidly changing situation rendered the matter of Churchill’s promotion irrelevant. The Germans took Fort Kessel. Afterward, they pressed on with an eye toward crossing the Nethe River and establishing a bridgehead on the other side. The German troops hastily assembled a ramshackle bridge across the river. When they attempted to cross it, they were met with a hail of bullets and shells from the Belgian defenders. The bridge collapsed into the river, forcing the Germans into a headlong retreat.

The Germans then tried to cross the Nethe at another location, erecting a shoddy but serviceable trestle bridge on the river between Lier and Duffel. By sheer coincidence, the location was defended by both British and Belgian troops. The British Royal Marines in particular were crack shots. They mowed down the Germans by the score. The Allied troops joked that the Germans now had a bridge of bodies over which they could cross.

Nevertheless, the Germans managed to get enough troops across the river to form a bridgehead, which forced the Allies to withdraw. It was the same story elsewhere along the river line. The Germans succeeded in establishing multiple footholds on the northern bank. The time had arrived for the Belgian Field Army to make good its escape, so King Albert gave the necessary order. What was left of the Royal Naval Brigades and the Belgian fortress troops received orders to fight a rearguard action.

Lavatory Negotiations: Churchill Agrees to More Raids

The Belgian government left the city by boat for Ostend on October 7. As for Winston Churchill, he returned to London. At that point, the Germans were chipping away at the second ring of fortresses—the older brick forts that dated back to the 1860s. The German heavy artillery made quick work of these weak structures. Moreover, German artillerymen had begun shelling the city. The big shells touched off fires. The Belgians added to the growing conflagration by torching their petroleum tanks.

The Germans were going to take Antwerp—that much was certain. But the British still had a few cards to play before they cashed in their chips. One of Churchill’s ideas turned out to be useful. The Royal Naval Air Service launched a series of 11th-hour raids into Germany, targeting the zeppelin sheds at Cologne and Dusseldorf.

When asked to approve new raids, Churchill rejected the idea. It was said that one of the pilots argued his case through the lavatory door while Churchill was using the toilet. The First Lord of the Admiralty finally agreed to get rid of this verbal tormentor. Squadron Commander Spencer Grey took off October 8 in a Sopwith Tabloid biplane at 1:20 pm to bomb the airship sheds at Cologne. It was 112 miles from Antwerp to Cologne, and the only minor issue was flying over neutral Holland’s Maastricht peninsula.

Unfortunately, Grey ran into a thick mist and could not find the zeppelin sheds. Cologne itself had better visibility, so he dropped his bombs on the main railway station right next to the city’s celebrated medieval cathedral. He returned home without incident by 4:45 PM. Another pilot, Flight Lieutenant R.L.G. Marix, had better luck. He found the zeppelin sheds at Dusseldorf, but they were heavily defended by machine guns. He dove and released his two 20-pound bombs from a height of 600 feet. One bomb did not do much damage, but the other scored a direct hit. The bomb crashed into the shed, and when it exploded it sprayed hot shrapnel into the sides of the zeppelin Z IX that was sheltered there. The airship’s hydrogen gas cells immediately ignited, causing a conflagration whose flames shot through the roof and 500 feet into the air. Coils of black smoke generated by the flames rose even higher.

The German machine guns protecting the facility scored a number of hits on Marix’s aircraft. Although the aircraft was badly shot up, Marix nursed his crippled airplane to within 20 miles of Antwerp. After ditching the aircraft, he borrowed a bicycle from a peasant and peddled his way back to the city. In the end, he was successfully evacuated at the last moment.

In the meantime, Antwerp was experiencing the chaos of impending defeat. Hundreds of thousands were fleeing the stricken city, with the booming reports of German artillery the funeral dirge of a soon-to-fall metropolis. At one point, a war correspondent reported as many as 150,000 people were trying to flee across the Scheldt River. The Germans pounded the old brick forts into submission one after another.

Were Churchill’s Actions in Vain?

General Deguise formally surrendered at his headquarters at Fort St. Marie on October 10, 1914. But Belgium’s king, its government, and the bulk of the Belgian Field Army successfully escaped. A handful of city officials led by Antwerp Mayor Jan de Vos also escaped. Even General Deguise, Antwerp’s military governor, had managed to give his would-be captors the slip after the surrender. He made his way to Holland, where he was interned for the rest of the war.

The Germans paraded into the city, but Antwerp was a ghost town. There were few inhabitants left to witness their triumph. The siege had lasted almost two weeks but, when all was said and done, the Germans had little to show for it. They had experienced heavy casualties, and the conquest of the city was something of a hollow victory. A disappointed General von Beseler remarked, “Such a fortress, and no general.” By this he meant that he had been denied the satisfaction of capturing Deguise and that the fortress was completely devoid of any military value.

The bulk of the 10,000 British Marines and Naval Division personnel had also managed to escape the closing German trap. The British experienced light casualties; specifically, they suffered 57 killed, 138 wounded, and 936 captured. But, unfortunately, in the confusion of the withdrawal some Naval Division units did not receive their orders until it was too late. About 1,500 men had little choice but to cross the border into Holland where they were interned for the remainder of the war.

After he returned to England, Churchill had to bear the brunt of a lot of negative publicity concerning the Antwerp affair. Critics pilloried the First Lord of the Admiralty as prone to grandstanding. Yet quite the opposite was true; he had gone to Antwerp with the blessing and approval of Prime Minister Asquith, Kitchener, and others. Prolonging the defense of Antwerp distracted the Germans to the extent that the Allies were able to retain control of the vital Channel ports linking France and Great Britain. After all was said and done, his efforts had produced a positive outcome for the Allied powers.