By David Alan Johnson

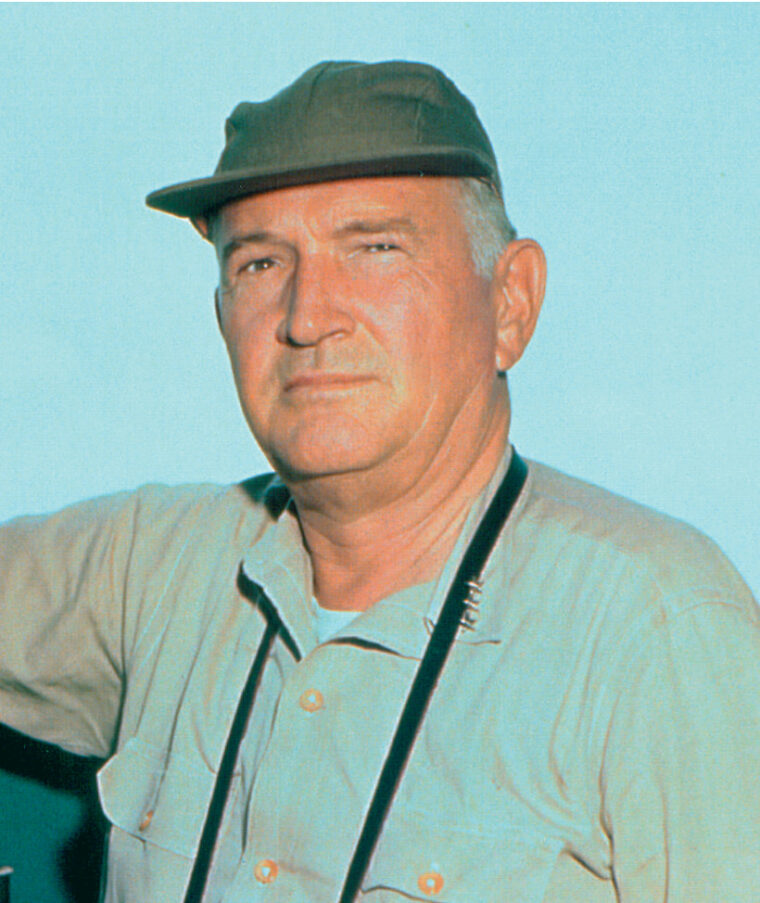

At 2:43 pm on October 24, 1944, one day before the Battle of Surigao Strait, Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf received a dispatch from Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, commander of the Central Philippines Attack Force. The message was straightforward and direct: “Prepare for night engagement,” and was duly logged aboard Oldendorf’s flagship, the heavy cruiser USS Louisville. Admiral Oldendorf, commander of the Leyte invasion fire support warships, was not surprised by the order. Naval intelligence had already been apprised of the fact that a Japanese force was on its way toward Leyte Gulf.

Avoiding Another Savo Island

At the height of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Admiral Oldendorf, a stocky man with a cheerful disposition, was to intercept Japanese naval Force C, under the command of Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura. That morning, Nishimura’s task group had been spotted by aircraft from the carriers Enterprise and Franklin. Another task group was sighted less than three hours later. This was Number Two Striking Force, under Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima. The main force, the First Striking Force under Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, had been intercepted by the submarines Darter and Dace the day before.

The three Japanese task groups were to rendezvous at Leyte Gulf, with Kurita entering from the north and Nishimura and Shima from the south, and attack the American transports and their escorts off the Philippine island of Leyte where American forces under General Douglas MacArthur had landed on October 20. If everything went according to the Japanese plan, the three task groups would arrive at Leyte Gulf at dawn on October 25, sink the American support ships off Leyte, and isolate the American troops on the island.

When he received the order to prepare for a night battle, Admiral Oldendorf decided that his best course of action would be to block Surigao Strait. The northern end of the strait leads into Leyte Gulf, and Oldendorf intended to place a battle line “squarely across the Leyte exit of the strait,” blocking Japanese access to the gulf. And he had enough warships at his disposal to accomplish what he had in mind.

The heart of Oldendorf’s battle line were the old battleships Mississippi, Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, California, and Pennsylvania. All but Mississippi were veterans of Pearl Harbor and had been either sunk or badly damaged by the Japanese attack. Now they were going to be given the chance to return the compliment.

The rest of the American force consisted of four heavy cruisers, including the Australian HMAS Shropshire, four light cruisers, and at least 28 destroyers including HMAS Arunta. “This was more than enough to take care of the Japanese southern force,” commented historian Samuel Eliot Morison. The Japanese Navy was well known for its lethal night torpedo attacks, and Oldendorf planned to overwhelm the enemy with superior numbers. “We didn’t want them to pull another Savo Island on us,” he commented. The Battle of Savo Island, fought by American and Japanese warships off Guadalcanal in August 1942, was one of the most humiliating defeats in the history of the U.S. Navy, and four Allied cruisers had been sunk. This time, nothing was being left to chance.

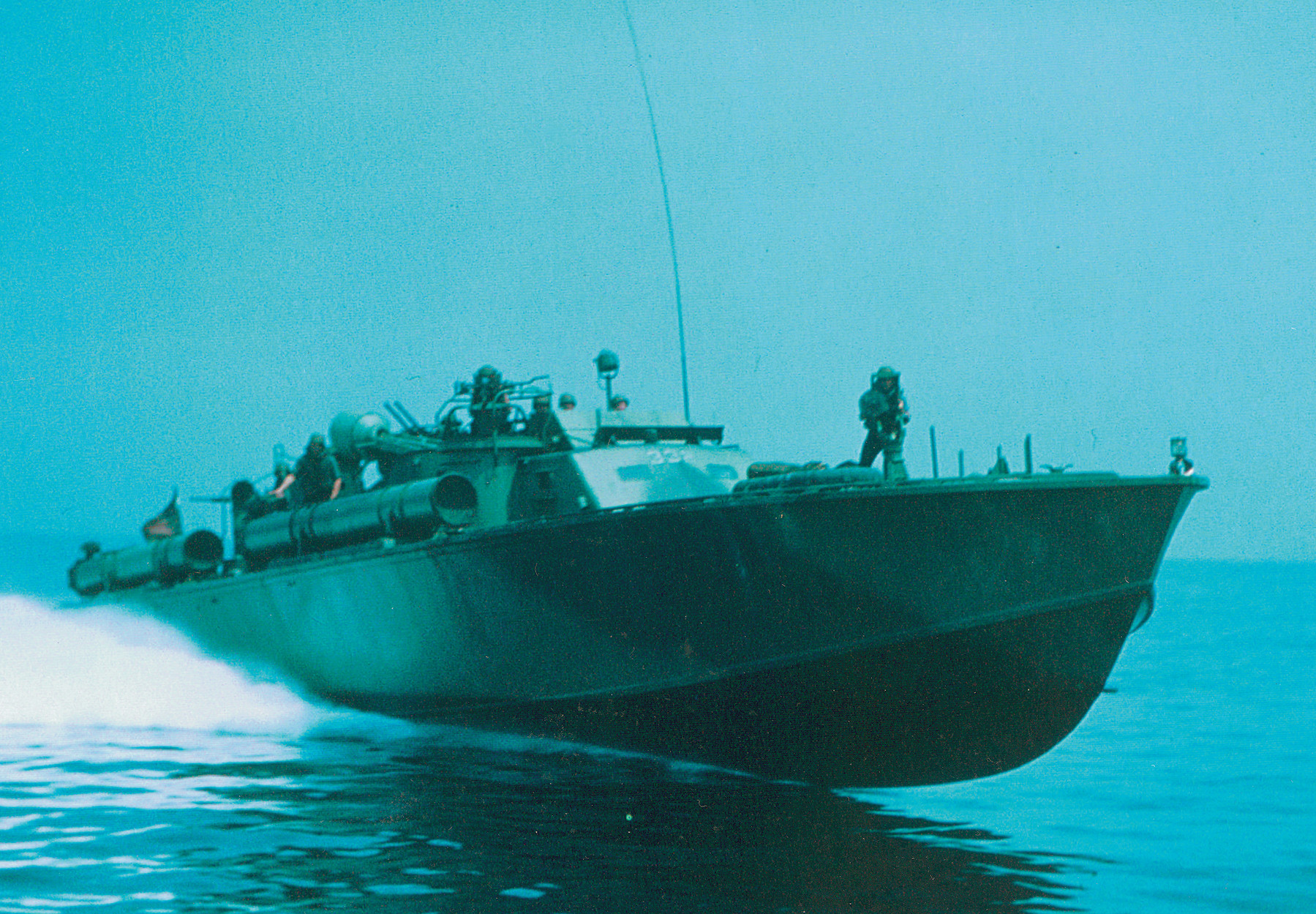

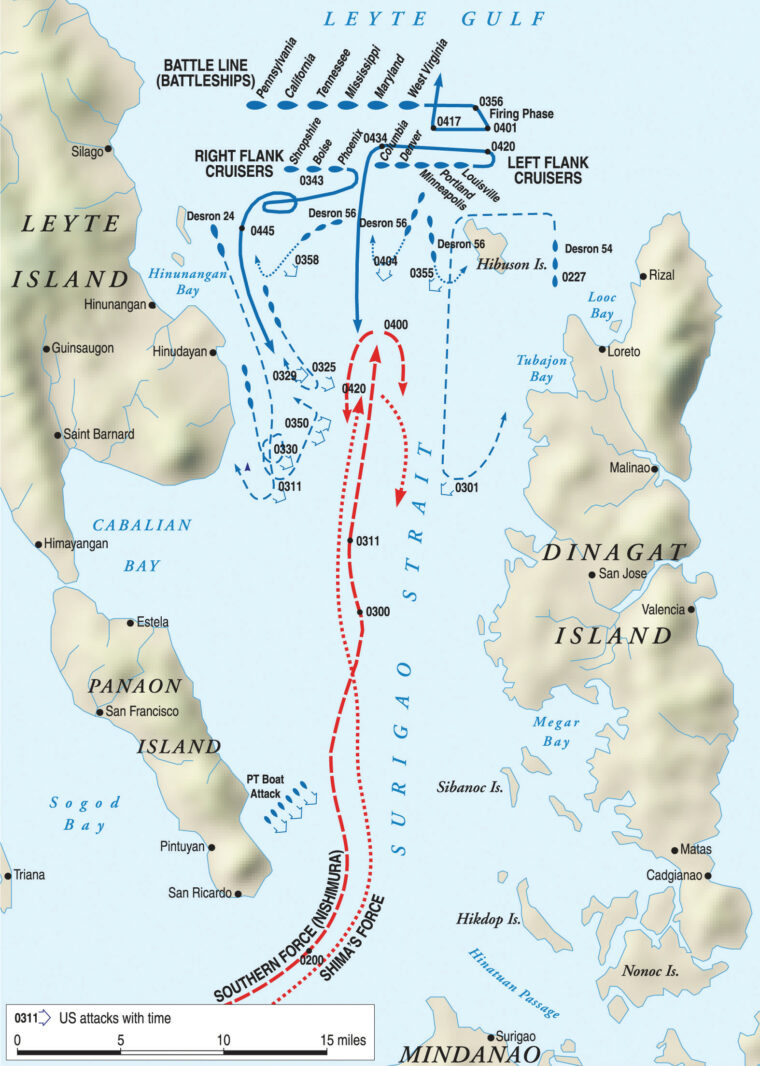

Admiral Oldendorf’s plan was fairly simple. First, every available PT boat would be stationed at the southern entrance to Surigao Strait. There would be 39 PT boats on patrol in the strait after dark; their instructions were to report the approach of the enemy and to attack with torpedoes. Next, the destroyers would attack with their torpedoes. The cruisers and battleships would then open fire with their large-caliber guns when the enemy came within range.

Scouting the Japanese Fleet

Admiral Nishimura’s Force C, which would be moving north toward Leyte Gulf, consisted of the old battleships Fuso and Yamashiro, the heavy cruiser Mogami, and four destroyers: Michishio, Yamagumo, Asagumo, and Shigure. Both Fuso and Yamashiro dated from World War I. Fuso was commissioned in 1915 and Yamashiro in 1917, although neither had taken part in any naval battles. Added armor protection, new boilers, and other improvements modernized both ships in the 1930s, but both were still considered too old and slow for an active role in the fleet. After Pearl Harbor, however, warships were needed for the confrontation with the U.S. Navy, and Fuso and Yamashiro were recalled from their training duties in the Inland Sea. Fuso was part of the Aleutian force during the Battle of Midway and took part in the reinforcing of Truk in 1943.

Nishimura’s force was much smaller than the American fleet it would be facing, but Admiral Oldendorf was not about to show any leniency. “If my opponent is foolish enough to come at me with an inferior force,” he later said, “I’m certainly not going to give him an even break.” Also, one of his destroyer squadron commanders, Captain Jesse Coward, had faced the Japanese at night off Guadalcanal. He knew what the Japanese were capable of doing with their long lance torpedoes and night tactics and was not about to let them do the same thing at Surigao Strait.

At 10:36 pm on the night of October 24, the crew of PT-131 picked up Nishimura’s group on radar. Visual contact was established 14 minutes later. About two minutes after this, the destroyer Shigure sighted the PT boats and began shooting. One shell hit PT-130 but failed to explode. The boat’s captain broke off contact at maximum speed and sent his contact report. Aboard Louisville, Admiral Oldendorf received the report just after midnight on October 25.

Each PT squadron in the strait went through the same sequence of events: making contact with the enemy, usually sending a contact report, firing torpedoes that missed, coming under fire from Japanese destroyers, and retiring behind a smoke screen. Admiral Oldendorf followed the progress of the PT reports closely; they confirmed that he did not need to make any changes to his battle plan. Of the boats that came under fire, 10 were hit and one was sunk. Total casualties were three killed and 20 wounded.

A Devastating Torpedo Salvo

Admiral Nishimura paid no attention to the PT attacks and kept advancing northward toward Leyte Gulf. His next contact with the enemy came at about 3 am, when he encountered the seven destroyers of Destroyer Squadron 54, commanded by Captain Jesse Coward. Captain Coward had already received notification of an unidentified contact at 2:40 am. The contact soon was confirmed to be a column of ships steering due north. Coward ordered his destroyers to attack with only torpedoes since their 5-inch guns would be ineffective against large enemy warships.

Admiral Nishimura’s column had its four destroyers in the lead, followed by Yamashiro, Fuso, and Mogami. Destroyer Squadron 54 split into two groups. Melvin, McGowan, and Remy would attack from the east, while Monssen and McDermut would make their approach from the west. Captain Coward, aboard Remy, closed with Nishimura’s ships at about 30 knots, making smoke. At 2:58, he turned his destroyers to the left, bringing torpedo tubes to bear, and gave the order, “Fire when ready.” Remy, Melvin, and McGowan began launching their torpedoes, firing 27 in about 75 seconds. It would take about eight minutes before they completed their runs of between 8,200 and 9,300 yards. With all torpedoes expended, Coward turned hard to port on a base course of 21 degrees, the three destroyers zigzagging individually and making smoke. None of the American destroyers suffered damage.

Strangely, Admiral Nishimura did not take any evasive action, even though he must have guessed that the American destroyers had fired torpedoes at his column. Several explosions were observed by sailors aboard Coward’s destroyers. A few minutes later, a large ship in the column slowed and began turning slowly to starboard. The battleship Fuso had been hit by a torpedo from the Melvin, but Admiral Nishimura continued to send orders to Fuso as though the ship were still undamaged.

While Captain Coward’s division was withdrawing, the destroyers McDermut and Monssen were still steaming due south. The destroyer division’s commanding officer, Commander Richard H. Phillips, turned to port to get into firing position, swinging his two destroyers back on a southerly course. A moment later, he ordered torpedoes to be fired when ready. McDermut began firing immediately; Monssen followed at 3:11.

This time, Admiral Nishimura did try to take evasive action. He turned 90 degrees to starboard, then 90 degrees to port, but this did not take him away from the torpedoes. At 3:20, flashes from explosions among Nishimura’s ships were observed aboard both destroyers. A searchlight beam, probably from one of the Japanese destroyers, lit up Monssen. Shell splashes followed almost immediately, and some were so close that columns of water drenched the aft guns of both Monssen and McDermut. The destroyers made smoke, changed course, and increased speed. The searchlight beam disappeared along with the bursting shells.

Destroyer Squadron 54 fired a total of 47 torpedoes. Captain Coward was positive that they had scored at least three hits. Actually, five of the torpedoes had found targets, resulting in the sinking of three enemy ships. McDermut’s torpedo salvo accounted for no fewer than three destroyers—Yamagumo, Michishio, and Asagumo. Yamagumo blew up and sank; Michishio was badly damaged and drifting and would sink shortly; Asagumo had her bow blown off but was able to make headway. Monssen scored a hit on Yamashiro, which continued steaming on course, but Melvin’s hit on Fuso would prove to be fatal.

No Losses

However, the attack of the destroyers was not over. Destroyer Squadron 24, under Captain K.M. McManes, also came south down the strait in two sections. The first section consisted of Hutchins, Daly, and Bache; the second of Killen, Beale, and HMAS Arunta. At 3:17, Commander A.E. Buchanan of the Royal Australian Navy heard Captain McManes’s order, “Boil up! Make smoke! Let me know when you have fired.” Two minutes later, the destroyer Yamagumo blew up, already hit by one of McDermut’s torpedoes. The light from the explosion was a great help to Commander Buchanan in making his run.

The fire from Yamagumo’s burning hulk might have helped the torpedomen see their targets, but it did not help to hit them. Arunta launched four torpedoes at a range of 6,500 yards. All four missed. Beale fired five torpedoes at 6,800 yards. These missed as well. Killen had better luck, firing five torpedoes at Yamashiro and hitting her once. Killen’s captain, Commander H.G. Corey, had been at Pearl Harbor and must have taken pleasure in torpedoing one of the enemy’s battleships. The second torpedo hit on Yamashiro slowed the ship to five knots, but only for a short time. The tough old battlewagon still made headway, and steadily regained speed.

Captain McManes’s three destroyers, Hutchins, Daly, and Bache, were also coming south at 25 knots. At 3:29, they began launching torpedoes. Admiral Nishimura’s neat column had disintegrated by this time. Yamashiro still pressed resolutely northward, now at about 15 knots. Shigure and Mogami, both still undamaged, fanned out on her starboard side. Fuso and the remaining destroyers were either drifting with the current or trying to withdraw to the south. This made for much more difficult shooting than Captain Coward had experienced.

McManes’s destroyers fired a total of 15 torpedoes at Nishimura’s force, or what was left of it. Bache also opened fire with her 5-inch guns at the damaged Japanese destroyers and was joined by Hutchins and Daly. The enemy returned an inaccurate fire of its own.

While this exchange was taking place, everyone’s attention was distracted by what happened to Fuso. The hit by Melvin’s torpedo—or possibly two torpedoes—had apparently caused internal fires that her damage control parties were not able to extinguish. The fires soon spread to one or more of the main magazines. At 3:38, the battleship exploded with a tremendous concussion and broke in half. Sailors on both sides witnessed the spectacle. The detonation was massive and was made even more spectacular by the moonless night. Both the bow and stern sections continued to float, drifting slowly away from each other. The two sections continued to drift until the forward section went down at 4:20. The stern sank less than an hour later.

As McManes’s destroyers began to withdraw, Hutchins launched her five remaining torpedoes at Asagumo. All five missed their target, but one hit Michishio, which had drifted into the path of the spread. Michishio blew up and sank immediately. Admiral Oldendorf’s destroyers had completely reversed the Japanese dominance in night torpedo attacks, which had plagued American forces at Guadalcanal two years earlier. The U.S. destroyers suffered no losses during the action.

“Launch Attack- Get the Big Boys”

Destroyer Squadron 56, commanded by Captain R.N. Smoot, had yet to engage the enemy. The Japanese force was still steaming northward toward Oldendorf’s battle line, and any further destroyer attack would have to be quick, before the battleships and cruisers began firing. At 3:45, even before McManes began his run, Smoot received the order, “Launch attack—get the big boys!”

Unlike the other squadrons, Destroyer Squadron 56 was deployed in three sections. Captain Smoot led Section One, which included Albert W. Grant, Richard P. Leary, and Newcomb. Section Two was under Captain T.F. Colney and consisted of Bryant, Hartford, and Robinson. Section Three, commanded by Commander J.W. Bouleware, was made up of Bennion, Leutze, and Heywood L. Edwards.

All nine destroyers steamed south at 25 knots. Colney’s three destroyers were the first to make contact with the enemy force, which now consisted of Yamashiro, Mogami, and Shigure, and began launching torpedoes at 3:54. Each destroyer fired five torpedoes, all of which missed. Bouleware’s section was next. Its targets were Yamashiro and Shigure. The two Japanese ships began firing as the destroyers launched torpedoes and kept firing as Bouleware’s ships retreated northward behind a smoke screen. Neither side scored any hits.

Captain Smoot’s division began launching torpedoes at 6,200 yards. Leary launched three torpedoes, Grant and Newcomb five each. A few minutes earlier, Yamashiro had altered course 90 degrees from north to west, directly across the torpedo tracks. Two explosions were seen aboard Yamashiro at 4:11, matching the interval it would have taken for Newcomb’s torpedoes to make their run. Yamashiro had already come under fire from Oldendorf’s battle line, explaining the change of course.

By this time, shellfire from both Japanese and American ships crisscrossed over the destroyers. Some of the shells glowed in the dark and could be seen against the black sky as they arced overhead. Both Leary and Newcomb managed to get clear of the crossfire, although they were bracketed by falling rounds. Albert W. Grant was not as lucky. Just as she was beginning her turn, the destroyer took her first hit. During the next 13 minutes, she received 18 more. Eleven of these were 6-inch shells from American cruisers. At 4:20, she was dead in the water. The crew plugged the shell holes with mattresses, tables, and anything available.

Around 5 am, Newcomb sent her medical officer and two corpsmen over to Grant by whaleboat—94 of the destroyer’s crew were wounded and 34 officers and men had been killed. Grant’s captain, a large, muscular man, went below and pulled several sailors out of the flooding engine room himself. An hour or so later, Newcomb took Grant in tow and pulled her out of the battle area. The destroyer was repaired and later took part in the Okinawa campaign.

“Modern War at Sea”

While the destroyers were making their torpedo attacks, Admiral Oldendorf’s battle line and flanking cruisers waited for Nishimura’s group to come within range of their guns. Explosions from the torpedo hits, along with the eruption of Fuso, were visible to anyone topside on any of the cruisers or battleships. Radar screens began to pick up the enemy at 3:23. The battleships and cruisers had been steering back and forth, east and west, across the northern end of Surigao Strait. At 3:30, they were all near the western side of the strait, steering east. Twenty-one minutes later Oldendorf ordered the cruisers to open fire; two minutes later the battleships joined in.

The situation was a Naval War College textbook exercise, at least from the American point of view. Admiral Nishimura’s force, now down to three ships—one battleship, one heavy cruiser, and one destroyer—continued steaming northward. Oldendorf was about to cross the T in a classic naval maneuver, which allowed the ships forming the horizontal stroke to bring all guns to bear, while the ships forming the downstroke could only fire their forward-facing guns at the enemy.

Of the American battleships, Tennessee, West Virginia, and California had the advantage of Mk 8 fire control radar. The radar data—the distance, speed, and course of the enemy—were fed into the gunnery computer and produced a firing solution before the enemy ships even came within range. Ammunition was in relatively short supply since the ships had been bombarding enemy shore installations and were carrying relatively few armor-piercing shells.

Yamashiro continued on a course of 20 degrees at 12 knots, firing at Denver, Columbia, and other left-flank cruisers. The battleship did not have any fire control radar and was limited to shooting at visible targets. The cruisers were closer and easier to see than Oldendorf’s battleships. Denver, Columbia, and Minneapolis were straddled by shell splashes.

The cruisers and battleships returned a devastating fire of their own. Every caliber shell from 6-inch to 16-inch came cascading down in the immediate vicinity of Yamashiro and Mogami. “This was modern war at sea,” wrote one commentator. “They fired at something they couldn’t see and it fired back.” Actually, Yamashiro and Mogami were firing at the cruisers and withdrawing destroyers and only managed to hit the unfortunate Albert W. Grant.

“The Most Beautiful Sight”

Aboard the battleships of both navies, the concussion from the big guns was staggering. Every time a salvo was fired, the recoil rocked the ship and seemed to push it sideways. The blast from the guns squeezed the breath out of the body and popped rivets out of the bulkheads. Shells weighing nearly a ton each rocketed out of muzzles at over 1,600 miles per hour. Thick clouds of cordite smoke burned the eyes and stuck in the throat. Flashless powder was being used, but the muzzle flashes still lit up each ship on this black night. An easterly breeze blew the smoke clear, a great help for visual spotting and observation.

West Virginia fired a total of 93 rounds of 16-inch armor-piercing shells, while Tennessee and California fired 69 and 63 rounds, respectively, of 14-inch ammunition. The other three battleships were hindered by their Mk 3 radar, which was far less effective in finding targets than the Mk 8 and resulted in dramatically fewer rounds fired. Maryland fired 48 rounds, its fire control managing to find Yamashiro by ranging on the splashes from West Virginia’s shells. Mississippi fired only one salvo, and Pennsylvania did not fire a shot all night long.

On the American left flank, Denver began firing at Yamashiro at 3:51. Minneapolis, Columbia, and Portland quickly joined in. Columbia alone fired 1,147 rounds in 18 minutes, equalling a 12-gun salvo every 12 seconds. Portland shifted fire to Mogami at 3:58, while Denver tried to stop Shigure but probably hit Albert W. Grant instead.

The right-flank cruisers concentrated fire on Yamashiro. Phoenix fired full 18-gun salvos on an average of every 15 seconds. Boise had also gone to rapid fire but was ordered to “fire slow and deliberate” to conserve ammunition. The Australian cruiser Shropshire started firing slowly but went to rapid fire after changing course to begin a westerly run across the strait. These cruisers fired a total of 1,181 rounds. Spotters observed large, bright flashes on Yamashiro and believed that their own gunfire was responsible.

Captain Smoot was in position to observe this display while his destroyers were withdrawing. “The devastating accuracy of this gunfire was the most beautiful sight I have ever witnessed,” he later reported. “The arched line of tracers in the darkness looked like a continual stream of railroad cars going over a hill. No target could be observed at first; then shortly there would be fires and explosions, and another ship would be accounted for.”

Aboard Louisville, Admiral Oldendorf received a message that Albert W. Grant and other destroyers were being hit by friendly fire, and he ordered all ships to cease firing at 4:09. Oldendorf wanted to give the destroyers time to get out of the battle area, but he also gave Nishimura some breathing room. Yamashiro turned 90 degrees and began to retire southward. In spite of the damage, the battleship was still able to make 15 knots, although she had sustained fatal wounds. No records exist to indicate exactly how many shell hits had penetrated Yamashiro’s armor, but a realistic estimate would be several hundred. At 4:19, the big ship rolled over and sank. Nishimura and most of the crew went down with the ship.

Mogami had already begun to withdraw, turning south at 3:53. As she made her way out of the strait, she was targeted by American cruisers and destroyers. By 3:53, Mogami was on fire and still taking hits. At 4:02, a shell, probably from Portland, exploded on the bridge, killing all officers including the captain. Other hits to the engine room slowed her to a crawl. She launched torpedoes at 4:01, but this was probably done as a precaution to prevent them from exploding.

Whatever the motive behind it, Mogami’s torpedo salvo certainly made the Americans take notice. The destroyer Richard P. Leary, which was heading north toward the battle line, reported that torpedoes were overtaking her at 4:13. The West Virginia, Maryland, and Tennessee turned due north with their sterns away from the approaching torpedoes, while the other three battleships headed westward. When Oldendorf ordered all ships to resume firing at 4:19, the battleships were out of position. It didn’t really matter, though, since there were no targets remaining. Yamashiro had gone down, and Mogami and Shigure were too far away.

The Battle of Surigao Strait’s Second Striking Force

By this time, Mogami was too badly damaged to be of any threat, and Shigure was leaving the battle area. But Vice Admiral Shima’s Second Striking Force had not yet made its presence known. Shima’s force was made up of two heavy cruisers, Nachi and Ashigara; the light cruiser Abukuma; and the destroyers Shiranuhi, Kasumi, Ushio, and Akebono. Throughout the night action, Shima had been receiving reports from Nishimura as he continued toward the strait. At midnight, he received a communiqué that Nishimura was being attacked by torpedo boats. About an hour later, his leading destroyers could see muzzle flashes from gunfire ahead. At about 3:15, the seven warships were attacked by torpedo boats. No hits were scored.

Ten minutes later, Shima’s luck took a turn for the worse—another torpedo fired by a PT boat hit the Abukuma, killing about 30 men and slowing the cruiser to 10 knots. The PT boat’s captain had actually been aiming at a destroyer in the column and hit Abukuma by mistake.

Undeterred, Shima continued northward. At about 4:10, he sighted two ships on fire and decided that they must be Fuso and Yamashiro. Actually, they were the drifting bow and stern sections of Fuso. Shima hurried due north to aid Nishimura. At about 4:20, just after Nishimura went down with Yamashiro, Shima’s radar detected what appeared to be two enemy ships at 13,000 yards, bearing 25 degrees. Nachi and Ashigara fired eight torpedoes each at the targets. The enemy ships were actually the two Hibuson Islands.

Shima had not heard from Nishimura for some time and tried to size up the situation himself. He could only guess at what had happened to Nishimura. His four destroyers had ventured ahead of the cruisers and could not find any targets, just a seemingly impenetrable smoke screen that had been laid down by American destroyers. At 4:25, Shima recalled his destroyers and sent a dispatch to headquarters in Manila: “This force has concluded its attack and is retiring from the battle area to plan subsequent action.”

Admiral Shima had exercised more discretion and common sense than Nishimura. Had he continued toward the American battle line, his cruisers and destroyers would have been chopped to pieces by Oldendorf’s battleships and cruisers. Shima’s force did, however, endure another bit of bad luck before leaving the area. The Nachi, Shima’s flagship, was overtaking the damaged Mogami, which appeared to be dead in the water. Mogami had not stopped, though. She was actually moving south at a greatly reduced speed, almost a crawl. Nachi’s captain misjudged both the speed and distance of Mogami, and the two ships collided at 4:30.

Nachi lost part of her port bow in the collision, and her speed was reduced to 18 knots. Mogami joined up with Shima’s column and steamed southward out of the strait. Shigure also joined the column but, before falling in with Shima’s force, the captain sent this dispatch to Combined Fleet headquarters: “C Force has been annihilated, location of enemy unknown, please send me instruction. I have trouble with my rudder, my wireless, my radar, and my gyro, and I received one hit.”

At 7:07, a half hour after sunrise, the Asagumo was discovered by the Denver and Columbia and three screening destroyers. The five warships had been sent down the strait to sink any lingering Japanese warships and proceeded to do just that. Asagumo’s bow had been blown off by Coward’s destroyers a few hours earlier, and her forward section was awash. The Japanese destroyer was quickly overwhelmed by a torrent of 5-inch and 6-inch shells but fought back with fire from her after turret. It was a futile gesture. Asagumo sank at 7:21; her survivors made their way toward the shore.

“One Hell of a Shootin’ Match”

Off the coast of Leyte, the sailors aboard the U.S. support vessels were too far away to see or hear the battle, but they did see the flashes of gunfire reflected in the clouds. They could tell that “one hell of a shootin’ match” was taking place. Nobody knew the outcome of the battle until morning, when reports began to filter in that the Japanese had been stopped. The news was not conclusive, mostly bits and pieces based on radio reports, but the word that was going around was certainly reassuring.

There was no need to worry. Oldendorf had certainly plugged Surigao Strait, as he had intended. No Japanese ship had come anywhere near Leyte Gulf, and what was left of the enemy fleet was retiring south.

Later in the morning, American Grumman TBF Avengers caught up with Mogami. A bomb hit on her engine room left her dead in the water. The destroyer Akebono took off the crew and sank the cruiser with a torpedo at 12:30. Of Nishimura’s force, only the Shigure survived to be torpedoed by the submarine USS Blackfin on January 21, 1945.

Shima’s force proved to be much luckier. All four of its destroyers escaped destruction at the Battle of Surigao Strait, along with the heavy cruiser Ashigara. Two days later, Abukuma, which had been struck by a PT torpedo at Surigao Strait, was hit several times by U.S. bombers. One of the bombs touched off the ship’s torpedo warheads, and the cruiser went down south of Negros Island. Nachi was sunk by dive- bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Lexington in Manila Bay on November 5.

“In no battle of the entire war did the United States Navy make so nearly a complete sweep as in that of Surigao Strait, at so little cost,” pronounced historian Samuel Eliot Morison. American casualties totaled 39 killed and 114 wounded, most of them aboard Albert W. Grant. No records of Japanese casualties exist, but they probably total in the thousands. Fuso and Yamashiro each had complements of 1,400 men, most of whom went down with their ships.

Surigao Strait also saw the end of the battle line in naval warfare. The development of the aircraft carrier meant that no line of battleships could withstand a sustained air attack.

A self-described “old sailor,” Morison called the Battle of Surigao Strait “a funeral salute to a finished era of naval warfare.” Romantic as well as sentimental, he went on to say, “One can imagine the ghosts of all great admirals from Raleigh to Jellicoe standing at attention as the Battle Line went into oblivion.”

My father was a gunner on the HMAS Shropshire during the Battle of Surigao Straits. He described it to me as the biggest and loudest fire works display he ever witnessed.

My Uncle Bob Hester was on the light cruiser Denver that night. He was an aircraft observer, way up on top. He said the gunfire lit up the night sky like it was daytime. Later on in his life, Uncle Bob’s hearing gave almost completely away, due to all the 5″ and 6″ gunfire he had to endure while on duty. The only thing they had for ear protection was cotton balls, which he said did little good.