By Donald J. Roberts II & Lawrence C. Schneider

In 1944, following the American victories in the South Pacific of operational commanders General Douglas MacArthur in western New Guinea and Admiral Chester Nimitz in the Marianas, American planners considered the next offensive against Japan’s empire. Later that year, with their gaining momentum, they would enter into the Battle of Leyte Gulf: arguably the largest naval battle in human history.

At the time, the final decision to either attack the Philippines or bypass them was made in September when Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey’s Third Fleet raided the Philippines as part of a series of attacks in preparation for invading the Palau Islands, 550 miles east of Mindanao, which is one of the Philippine Islands. During the raids, Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s carriers launched their planes against enemy airfields and naval facilities located from the central Philippines south to Mindanao. Pilots from Mitscher’s Task Force 38 reported they had destroyed 478 planes and had sunk 59 ships.

This victory prompted Halsey to radio Nimitz to suggest that the plans to invade Mindanao in the south be canceled, because the Japanese were now weakened. He proposed that new plans be made to attack the Philippine island of Leyte. At the same time, Halsey reported that the enemy’s defenses on the Philippines were weak and could be overcome in a timely manner.

In preparation for American offensives, the Japanese had outlined a series of operational plans that came on the heels of the Marianas campaign. Not fully understanding where the Americans would strike next, Japanese strategists developed four Sho (Victory) plans. Sho-1 called for the defense of the Philippines, Sho-2 provided for the defense of the Ryukyus Islands, Sho-3 protected the southern and central portions of Japan, and Sho-4 called for the defense of northern Japan as well as the Kuril Islands.

Japan’s Most Powerful Battleships: The Yamato and Musashi

Each Sho plan comprised an in-depth scheme that implemented offensive as well as defensive tactics. The Sho plans were, in essence, Japan’s attempt to fight and win the decisive battle wherever it should occur.

For the defense of the Philippines, Sho-1 was designed as a four-part plan. First, the Fourteenth Area Army, commanded by General Tomoyuki Yamashita, was to construct strong defensive positions well inland and out of the range of American naval guns. Next, the battleships Yamato and Musashi, the largest in the Japanese Navy, were to engage and destroy the American invasion fleet. At the same time, the Yamato and Musashi would be supported by land-based planes. To complete the plan, a diversionary force of four carriers would try to lure the American covering force away from the invasion fleet, freeing the Yamato and Musashi to defeat the invaders.

On the American side, plans were gelling as well. Because Roosevelt had not committed to a unified command for the invasion of the Philippines, two separate commands were to be used. The first was MacArthur’s; he was to lead the Leyte invasion force, which was itself divided into two commands: Lt. Gen. Walter Kruger’s Sixth Army and Vice Adm. Thomas Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet.

The Seventh Fleet comprised a Northern Attack Force (Task Force 78), commanded by Rear Adm. Daniel Barbey, and a Southern Attack Force (Task Force 79), commanded by Vice Adm. Theodore Wilkinson. Both commanders were given the objective of landing and supporting the ground forces of Kruger’s Sixth Army.

To facilitate landing-beach bombardment and to coordinate tactical air strikes against targets on shore, Kinkaid created Task Force 77. Task Group 77.2 was designated the Fire and Support Bombardment Group for the invasion and was led by Rear Adm. Jesse Oldendorf. Task Group 77.4 was led by Rear Adm. Thomas Sprague.

Sprague’s command was an escort carrier group that he separated into three sections. Sprague himself maintained command of “Taffy 1.” Rear Adm. Felix B. Stump commanded “Taffy 2,” and Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague (no relation) commanded “Taffy 3.”

Charged with covering MacArthur’s invasion forces was the second command, Nimitz’s Third Fleet, which for this operation was commanded by Admiral Halsey. Halsey planned to use Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Force to provide the necessary air support—by this stage of the Pacific war, the blanket of aircraft that a carrier force provided for an amphibious invasion had become a necessary ingredient for a successful landing.

Mitscher’s Task Force 38 was arranged into four groups. Commanding TG 38.1 was Vice Adm. John McCain (grandfather of current Arizona Senator John McCain). TG 38.2 was commanded by Rear Adm. Gerald Bogan. Rear Adm. Frederick Sherman commanded TG 38.3, and Rear Adm. Ralph Davidson commanded TG 38.4.

Employing Sun Tzu’s Art of Deception

As this powerful American force began to assemble for the invasion of the Philippines, the Japanese put the gears in motion for Sho-1 and finalized their tactical plans for the coming battle. Japanese leaders knew that the struggle for the Philippines could be their final opportunity to stop the mounting American pressure on their empire. At the same time, an American victory there would effectively divide Japanese military forces. Forces to the north would be cut off from precious oil supplies in the East Indies. The elements of the Japanese military that remained south of the Philippines would be denied supplies from the homeland, namely ammunition.

Admiral Soemu Toyoda, commander of Japan’s Combined Fleet, knew he was facing an enemy with superior power. To engage Kinkaid’s amphibious force was challenge enough, but with Halsey’s Third Fleet prowling the waters Toyoda realized that victory in the upcoming fight would be difficult, if not impossible. Toyoda believed that the only hope for a successful Japanese outcome lay in the “age-old weapon” that dates back to the principles of Sun Tzu: deception.

As a part of Sho-1, Toyoda devised an offensive plan that encompassed four naval forces. The main battle force was commanded by Vice Adm. Takeo Kurita. American commanders labeled this the Center Force. Kurita’s objective was to sail from Brunei and attack the American invasion fleet at Leyte from the north by way of the Sibuyan Sea. The Southern Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura, was to sail from Brunei as well. Nishimura’s ships were directed to attack the American invasion fleet from the south by first sailing through the Mindanao Sea. Basically, Toyoda was planning a double envelopment of the American naval forces as they concentrated off the invasion beaches. A third force, sailing from Japanese home waters, was commanded by Vice Adm. Kiyohide Shima. He was given the task of supporting Nishimura in the southern envelopment.

Finalizing Toyoda’s tactical plan was Vice Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa’s Northern Force. Ozawa was to sail from the home waters as well and serve as a diversionary force to lure Halsey’s carriers away from the invasion fleet. This action was to take place in the northern reaches of the Philippine Sea. Once Halsey’s main battle carriers were engaged with Ozawa’s force, Kurita, Nishimura, and Shima would pounce on the unprotected amphibious force and decisively destroy the invaders.

Facing the daunting strength of the Americans, the best Toyoda could hope for was to defeat the invaders as they stood with “one leg ashore, one leg afloat” on the invasion beaches. Toyoda and his advisers believed that a Japanese victory might influence the approaching American presidential election. They reasoned that an American defeat might oust Roosevelt from the White House, thus setting up the possibility of a new war policy and hope for a reasonable end to the war for Japan.

Prelude to the Battle of Leyte Gulf: Rangers Capture the Outer Islands, and Oldendorf Moves into Position

On October 17, roughly five days before the Battle of Leyte Gulf would properly begin, the vanguard of the American invasion was approaching the outer islands guarding the opening to the gulf. Within hours Toyoda had issued orders that put all his forces in motion. By noon on the 18th, U.S. Army Rangers had captured the outer islands around Leyte Gulf. At this point Admiral Oldendorf maneuvered into the gulf with TG 77.2 and began to shell the enemy positions behind the invasion beaches. The bombardment would last 36 hours.

While Oldendorf’s ships supported General Krueger’s troops as they fought inland, the American ships were continually under fire. Counterbattery fire from shore was responsible for a number of casualties onboard several ships. At the same time, the ships of TG 77.2 were constantly under attacks from land-based enemy aircraft. From the 18th to the 24th, Oldendorf’s crews received little rest. Air attacks day and night left the sailors at general quarters almost continually.

Farther out to sea, Halsey’s task groups, which had expected reaction from the main Japanese naval forces by now, had met with very little enemy response to the American invasion. Consequently, Halsey dispatched McCain’s TG 38.1 to Ulithi, over 800 miles east, to refuel the task group and give the ships’ crews some rest; many of the crews had seen 10 months of duty at sea without a break. Davidson was slotted to sail toward Ulithi the next day for the same reasons. This would leave the balance of Halsey’s Task Force 38 to deal with the Japanese Navy should it show up.

Indeed, Admiral Halsey did not know the whereabouts of any major Japanese naval force at this point; moreover, owing to the success of the American air attacks before the invasion, Halsey and MacArthur expected minimal enemy reaction when it did occur.

The first real news about the location of any Japanese naval counterattacks against the invasion forces came in the early hours of October 23. As Admiral Kurita’s Center Force began to steam between Palawan and Mindoro (Palawan Passage), it was discovered by two American submarines.

In the ensuing battle, the Darter and Dace managed to sink two of Kurita’s heavy cruisers, one of which, the Atago, was Kurita’s flagship. Another heavy cruiser was badly damaged by the sub attacks as well. More important, this contact alerted Halsey and Kinkaid to the whereabouts of at least a portion of the enemy’s naval forces.

Despite the damage, Kurita continued forward in his role in the pincer movement. Halsey immediately recalled McCain’s task group, canceled Davidson’s departure, and ordered an all-out reconnaissance of all navigable approaches to Leyte Gulf.

During the daylight hours of the 23rd, Task Force 38 was busy taking on fuel and ammunition from its supply ships with the understanding that the next day would bring some type of action against the enemy.

Musashi’s Downfall

On the morning of the 24th, planes from Bogan’s TG 38.2 spotted Kurita’s force steaming through the Sibuyan Sea toward San Bernardino Strait. At the same time, planes from Davidson’s TG 38.4 found Nishimura’s Southern Force as it maneuvered through the Sulu Sea. Shima’s Southern Force was spotted by land-based Fifth Air Force planes based on Owi, Biak, and Noemfoor. Ozawa’s Northern Force was not located until later in the day. Halsey took tactical control of all Task Groups and ordered them to attack Kurita’s Center Force.

The subsequent fight is known as the Battle of Sibuyan Sea. During the battle, planes from Task Force 38 made four attacks against the Center Force, sinking the battleship Musashi and badly damaging the heavy cruiser Myoko. Kurita’s force became scattered, and in the confusion, Halsey’s pilots reported that Kurita was withdrawing his ships back to the west out of the Sibuyan Sea.

The American aircraft carrier Princeton from Sherman’s TG 38.3 was sunk by a single land-based enemy bomber during the battle. The light cruiser Birmingham was heavily damaged as well; she had come alongside Princeton to take off survivors when the aircraft carrier blew up.

Relying on reports from his pilots that Kurita was retiring westward, Halsey decided to abandon the northern flank of the invasion fleet and sail farther north in search of Ozawa’s Northern Force. This, of course, is exactly what the Japanese had hoped Halsey would do. Before the battle, Halsey had established an emergency plan to protect the Seventh Fleet in his absence. It called for the formation of Task Force 34. This force was to consist, if needed, of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers from Bogan’s and Davidson’s task groups. Task Force 34 would be formed if Kurita’s force emerged from the San Bernardino Strait.

When Admiral Kinkaid learned that Nishimura and Shima were approaching from the south, he alerted his force to be ready for a night action. At the same time, he believed that “any major enemy naval force approaching from the north will be intercepted and attacked by Third Fleet covering force.”

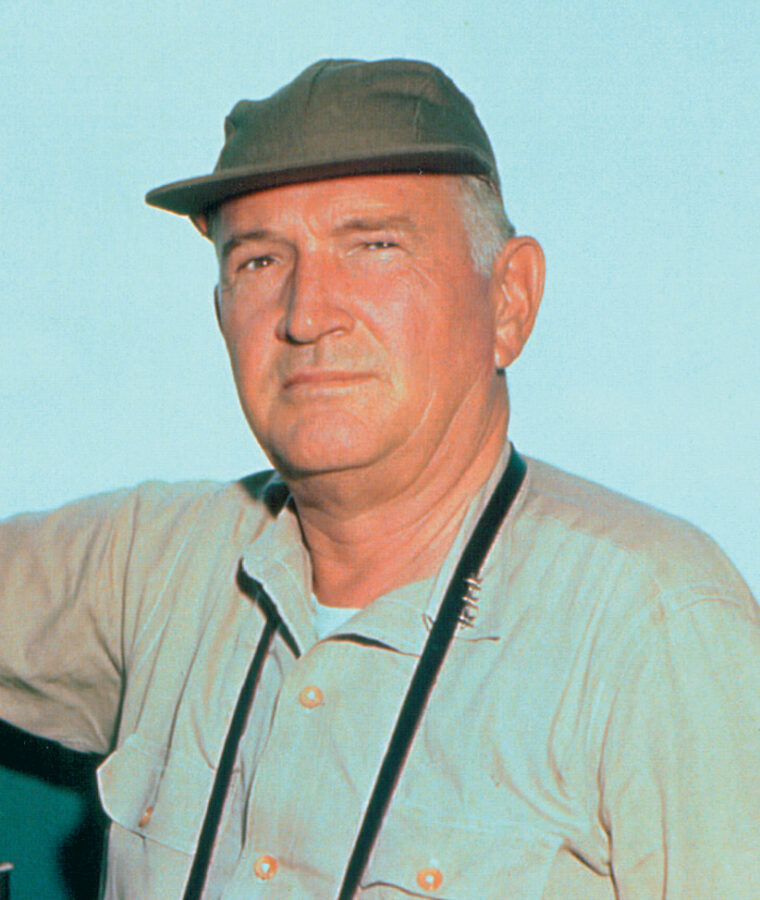

Reacting to Kinkaid’s orders to prepare for a night battle against enemy forces coming up from the south, Admiral Oldendorf knew that his primary role in the upcoming battle would be to protect the invasion forces rather than engage the enemy in an all-out shooting match in the Surigao Strait.

Untrained Crews Delivered Torpedo Attacks Against Nishimura and Shima

There are two sea approaches to Leyte Gulf. The broad eastern entrance was where Sprague’s Taffy Groups’ escort carriers were arrayed. The southern approach was Surigao Strait, which is where Admiral Oldendorf prepared to defend the invasion. At his disposal were all of the Seventh Fleet’s fire support ships. This substantial force consisted of six battleships (five of which had been damaged during the attack on Pearl Harbor), four heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, 28 destroyers, and 39 PT boats.

Finalizing his tactical plans, Admiral Oldendorf formed his ships into four main sections. He planned on using Lt. Cmdr. R.A. Leeson’s PTs as scouts. The small, swift boats could operate freely in the narrow confines of the strait while they patrolled as far south as the Mindanao Sea. Their orders were to “report all contacts, surface or air, visual or radar, and attack independently.” Although most of the PT crews had very little torpedo training, they were instructed to “intercept” and “deliver torpedo attacks” against Nishimura’s and Shima’s Southern Forces.

Oldendorf knew that the narrow strait would force the enemy into a single line as they sailed toward him. As a result, he divided his destroyer force into two groups, each to the Japanese flanks. Oldendorf planned on aligning his cruisers and battleships on an east-west axis, thus perpendicular to the Japanese line. By doing so, Oldendorf would complete the classic naval tactic of “capping or crossing the T.”

At 10 o’clock on the night of October 24, Kurita radioed Nishimura that he and his force would arrive at the Battle of Leyte Gulf at 11 o’clock the next morning. Knowing this, Nishimura should have slowed to rendezvous with Kurita at the designated time. Instead, Nishimura kept his speed steady. If there were enemy ships in Surigao Strait, he reasoned, it would be better if the battle took place at night because the Japanese had proven themselves superior to the Americans during night engagements.

Nishimura’s Southern Force comprised two battleships, a heavy cruiser, and four destroyers. In support, Vice Adm. Kiyohide Shima’s Second Southern Force contained two heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, and seven destroyers. Nishimura’s failure to slow ensured that Shima would not be able to catch up, thus preventing a massing of their firepower. Apparently, Nishimura was determined to follow through with Admiral Toyoda’s orders and sneak through Surigao Strait then “dash to the attack.”

By now, the PT boats were on station, lying in wait for the enemy ships. The PTs were arrayed in three-boat sections along the coasts of Mindanao, Leyte, and Bohol, ready to report the enemy’s approach. The opening round in Oldendorf’s ambush was about to take place.

Only PT 493 was Sunk in Action

At 11:30 pm, the southernmost PT section made radar contact with Nishimura’s ships. Leading the formation were the destroyers Michishio, Asagumo, Yamagumo, and Shigure. They were followed by Nishimura’s two battleships, Yamashiro and Fuso. The heavy cruiser Mogami sailed at the rear of the single-file column.

Before the small PTs could maneuver into effective torpedo range, guns from the Japanese ships opened up on them. In the darkness, many of the PTs became separated. They played cat and mouse with Nishimura’s force in piecemeal attacks for three hours. As rain squalls moved through the area at frequent intervals, Nishimura’s ships were able to defend themselves by illuminating the area with star-shells and shelling the elusive PTs whenever they presented themselves. Many boats had parts of their plywood decking and sides ripped away, deck guns destroyed, radios shot to pieces, and many men wounded and killed. But PT 493 was the only boat sunk during the action.

Moreover, throughout the series of individual battles, Leeson’s PTs were able to keep Oldendorf informed of the progress of Nishimura’s force. As for damaging the enemy, the PTs’ only real success was scored by PT 137. On a torpedo run against one of Nishimura’s destroyers, the American torpedoes missed their mark, but minutes later the light cruiser Abukuma was hit instead. The Abukuma was one of Shima’s ships sailing behind Nishimura. Thirty Japanese sailors were killed, and the Abukuma was slowed to 10 knots. Falling out of formation, she was sunk by Fifth Air Force planes two days later.

Following the battle, Admiral Nimitz wrote that “the skill, determination and courage displayed by the personnel of these small boats is worthy of the highest praise. Their contact reports … gave ample warning to our own main body … threw the Japanese command off balance and contributed to the completeness of their subsequent defeat.”

Now that his ambush was set in motion, Oldendorf feared that Nishimura’s radar would detect the presence of the American main battle line. The last thing Oldendorf wanted was to be enticed into chasing Nishimura if he turned and fled. Oldendorf, whose job it was to protect the invasion fleet, did not want even a single enemy ship to slip by undetected.

Oldendorf’s fears were needless at this point. The PTs did not even slow the enemy down. Feeling proud that, once again, the Japanese Navy had proven itself at night, Nishimura steamed on into Surigao Strait.

In a message to Kurita, Nishimura stated, “several torpedo boats sighted but enemy situation otherwise unknown.” Realigning his forces, Nishimura continued on into the night.

On picket duty behind the PTs was Destroyer Squadron 54 commanded by Captain J.G. Coward. His orders were to engage the enemy ships with torpedoes while not giving away his location.

“Fire When Ready!”

Coward divided his squadron into two divisions, one to the east of Nishimura’s column (Division 107) and one to the west (Division 108). Realizing that the PTs had not seriously damaged the enemy, Coward decided to attack right away.

Commander R.H. Phillips, leading the McDermut and Monssen on the west, and Coward, on Nishimura’s east flank with the Remey, McGowan, and Melvin, planned to launch their “fish” when they approached the ideal firing angles—40 to 60 degrees off the enemy’s bows.

Seemingly unaware that he was about to be ambushed for the second time that night, Nishimura had arranged his force into battle formation with his four destroyers leading, followed by his two battleships, and the cruiser bringing up the rear.

At 2:56 am, the two enemy forces spotted each other. Coward ordered smoke to try to hide his force and a few minutes later ordered, “Fire when ready!” At ranges from 8,200 to 9,300 yards, Coward’s three destroyers launched 27 torpedoes in less than a minute and a half. Turning to the north, Coward’s ships retired, making more smoke and “zigzagging independently” as the Yamashiro fired 5-inch shells at them. At this range, it would take eight minutes for the American torpedoes to reach their targets.

At 3:08, Coward’s men reported explosions to their rear. Immediately, the Fuso slowed and fell out of formation. Minutes later, Phillips’ McDermut and Monssen went into action from the west. By this time, Nishimura began making defensive maneuvers but they had little impact on the battle in the narrow strait. Torpedoes from the McDermut hit three of Nishimura’s destroyers: The Yamagumo blew up and sank, the Michishio slowed and began to sink, and the Asagumo had her bow blown off but was able to slowly retire. Speeding away to the north, the two American destroyers had to dodge enemy gunfire as well as marauding American PTs still searching for targets in the night.

Next to engage the enemy was Captain K.M. McManes’ Destroyer Squadron 24. The explosions from Coward’s and Phillips’ attacks helped to illuminate Nishimura’s remaining ships for McManes’ two sections. The first, which McManes commanded, consisted of the Hutchins, Daly, and Bache. Section Two, commanded by Commander A.E. Buchanan (Royal Australian Navy), was made up of the HMAS Arunta, followed by the Killen and Beale. McManes’ orders to Buchanan were simple: “Boil up! Make smoke! Let me know when you have fired.”

“Launch Attack—Get the Big Boys!”

At 3:23, Buchanan’s ships began launching torpedoes, 14 in all. One of them slammed into the Yamashiro, slowing her to five knots. As McManes led his destroyers into the attack, the Hutchins fired five “fish,” all of which missed the bowless Asagumo; however, minutes later one of the torpedoes hit the damaged Michishio, which then blew up and sank. Before retiring quickly to the north, Squadron 24 received heavy return fire from the Mogami and Yamashiro.

Admiral Oldendorf’s final destroyer force, Destroyer Squadron 56 commanded by Captain R.N. Smoot, received an order at 3:35 to “Launch attack—get the big boys!” Smoot was prepared to attack Nishimura from both flanks as well. To the east of the enemy line were Sections 1 and 2. Smoot commanded Section 1, which comprised the Grant, Leary, and Newcomb. Section 2, commanded by Captain T.F. Conley, consisted of the Bryant, Halford, and Robinson. Positioned on Nishimura’s west flank was Commander J.W. Boulware’s Section 3, which included the Bennion, Leutze, and Edwards.

As Smoot’s squadron began its final run toward Nishimura’s ships, Oldendorf’s main battle line of cruisers and battleships opened up on Nishimura’s column. Gunnery officer James Holloway, on board the Bennion, was surprised by the slowness of the huge projectiles, “They almost hung in the sky, taking 15 to 20 seconds in the trajectory before reaching their targets,” he remembered.

Smoot’s Section 1 drew closer to the enemy ships than any other squadron during the night. As a result, the Grant received heavy fire from Nishimura’s remaining ships. At the same time, American fire-control officers on board other ships believed the Grant to be a Japanese warship and soon the American destroyer began taking friendly fire as well. Within minutes, the Grant became dead in the water. By the end of an hour, nearly every man on board had performed feats that were recognized in the Grant’s battle report. These acts of heroism, as the sailors fought bravely to help each other and to keep their ship afloat, paid tribute to the American fighting spirit during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Smoot’s Section 1 drew closer to the enemy ships than any other squadron during the night. As a result, the Grant received heavy fire from Nishimura’s remaining ships. At the same time, American fire-control officers on board other ships believed the Grant to be a Japanese warship and soon the American destroyer began taking friendly fire as well. Within minutes, the Grant became dead in the water. By the end of an hour, nearly every man on board had performed feats that were recognized in the Grant’s battle report. These acts of heroism, as the sailors fought bravely to help each other and to keep their ship afloat, paid tribute to the American fighting spirit during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Brilliant Explosions Could be Seen Lighting up the Deck of the Enemy Battleship

As the Grant fought for her life, Sections 2 and 3 moved in to attack. Captain Conley noticed gun flashes to the south. Believing them to be enemy fire, he signaled the rest of Section 2, “This has to be quick. Stand by your fish.” Just then, exploding shells began to shower the American destroyers with geysers of water. Immediately, Conley’s ships fired 15 “fish” and retired northward, making smoke as all torpedoes missed the enemy ships.

Commander Boulware’s destroyers closed and fired an array of torpedoes that all missed their intended targets as well. Conley’s and Boulware’s withdrawal was covered dramatically by Admiral R.S. Berkey’s main battle line. The Right Flank cruisers, Phoenix, Boise, and HMAS Shropshire had opened up on the Yamashiro at 16,600 yards. Within seconds, brilliant explosions could be seen lighting up the deck of the enemy battleship.

Oldendorf’s Left Flank cruisers Louisville, Portland, Minneapolis, Denver, and Columbia also scored numerous hits on the Yamashiro. Admiral G.L. Weyler’s battleships Mississippi, California, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and West Virginia had been firing their big 14- and 16-inch guns at 40-second intervals, which soon turned the Yamashiro into a blazing hulk. Steering to port and retiring southward, she soon sank with most of her crew, including Admiral Nishimura.

The accuracy of Oldendorf’s big guns was amazing to the officers who witnessed the 20-minute barrage. Captain Smoot reported that it “was the most beautiful sight I have ever witnessed. The arched line of tracers in the darkness looked like a continual stream of lighted railroad cars going over a hill.” Admiral Oldendorf’s ability to cross the enemy’s line, thus creating the always-strived-for “T” in naval tactics, had produced a final deathtrap for Nishimura’s force. Only the destroyer Shigure managed to escape the American ambush. The damaged Mogami, in her attempt to withdraw, had collided with Admiral Shima’s flagship cruiser Nachi as Shima steamed north on Nishimura’s rear. Having already been attacked by a number of PT boats, the collision with the Mogami became the final straw for Shima. He turned his ships around and withdrew.

As dawn approached, Oldendorf ordered his battleships to stay in position but instructed the remaining ships to pursue the Japanese and “polish off enemy cripples.” Later in the morning, planes from Admiral Sprague’s escort carriers located the Mogami and sank her.

The battle in Surigao Strait was a masterful tactical achievement. Admiral Oldendorf’s planning, ship dispositions, and maneuvers had led to almost complete annihilation of the enemy force.

In the next phase of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Oldendorf was ordered to stop his pursuit of Shima, concentrate his force once again, and sail north to support Admiral Sprague’s Taffy 3 Escort Group, which suddenly was being attacked by Admiral Kurita.

Kurita had turned around in the San Bernardino Strait, emerged out into the Philippine Sea, steamed down the coast of Samar Island, and caught Sprague’s Taffy 3 group by surprise.

The Beginning of the End for All Japanese Forces in the Philippines

Thinking he was attacking one of Halsey’s fast carrier groups, Kurita ordered his ships forward in an uncoordinated attack. Although this Japanese assault was piecemeal, the Japanese ships were able to sink one of Sprague’s escort carriers, the Gambier Bay, destroyers Johnston and Hoel, and the destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts. In addition, land-based kamikaze planes sank another of Sprague’s escort carriers, the St. Lo.

Although Sprague’s airmen had been trained for, as well as armed for, air support of ground forces ashore, they boldly attacked Kurita’s force. They were able to sink three of his cruisers, the Chikuma, Chokai, and Suzuya. Before she sank, the American destroyer Johnston had been able to torpedo a fourth cruiser, the Kumano, and send her to the bottom. Following repeated air attacks—many from Taffy 1 and Taffy 2—Kurita radioed Tokyo telling his commanders that he was retiring to San Bernardino Strait and then to Brunei.

The final chapter of the battle witnessed Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet in action. As Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet was fighting for its life off Samar Island, Halsey was swallowing the Sho-1 bait, which was Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa’s Northern Force.

Because Ozawa’s Northern Force was a decoy, he had very few aircraft onboard his carriers. Beginning the battle with only 166 planes, his air force now numbered a mere 29 as Halsey’s fast carrier groups approached.

Early on the 25th, Task Groups 38.2, 38.3, and 38.4 located and then attacked Ozawa’s ships. By the end of the day, successive waves of American planes sank four enemy carriers, the Zuikaku, Zuiho, Chiyoda, and Chitose. The sinking of the Zuikaku was a pleasant sight for the American flyers. She was the last surviving of the six Japanese carriers used in the Pearl Harbor attack. One of Ozawa’s destroyers, the Akitsuki, was sunk by American planes as well. As Ozawa began his withdrawal from the Philippine Sea, American cruisers from Halsey’s Task Force 34 succeeded in sinking another enemy destroyer, the Hatsuzuki.

By the 26th, two American submarine wolfpacks were able to send another destroyer, the Nowaki, and the light cruiser Tama to the bottom.

The Imperial Japanese Navy’s defeat at the Battle of Leyte Gulf signaled the beginning of the end for all Japanese forces in the Philippines. At the same time, the American victory drained most of Japan’s remaining resources and materiel, thus ensuring an American triumph in the Pacific.

Admiral Oldendorf’s engagement with Nishimura marked the last time in history that ships of the line fought each other in the traditional sense in a major battle. His brilliant victory in Surigao Strait had in no small way helped to secure the victory in the Philippines for the Allies. (Get an in-depth look at all the events that shaped the Second World War by subscribing to WWII History magazine.)

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments