By Mark Simner

“I must tell you something…. I took part in a mass killing the day before yesterday.

[When we shot the Jews brought by] the first truck, my hand trembled somewhat during the shooting, but one gets used to it. By the tenth truck, I was already aiming steadily and shooting accurately at the many women, children, and babies…. The babies went flying through the air in a big arc and we shot them down as they flew, before they fell into the grave or into the water…. Damn it! I never saw so much blood, [feces], bones, and flesh. Now I can understand the phrase ‘drunk with blood.’”

These grotesquely chilling words, written in a letter to his wife in October 1941, were penned by Walter Mattner, an Austrian SS and police lieutenant attached to Einsatzkommando 8 of Einsatzgruppe B. In September 1941, he had arrived in the Byelorussian city of Mogilev, where he took a terrifyingly enthusiastic part in an act of mass murder on October 2-3.

In the space of just a few hours, Mattner and his “blood-drunk” colleagues had slaughtered more than 2,200 men, women, and children in cold blood, disposing of their bullet-riddled corpses in a nearby forest. The victims had one thing in common: they were all Jewish and, for this alone, the Nazis had deemed them unworthy of life.

This act was just one example of the many mass killings conducted by the notorious Einsatzgruppen in Eastern Europe during World War II. Although estimates vary, it is believed that these “Special Task Forces” murdered around 1.5 million Jews during their period of operation. Other victims included local intelligentsia, Soviet political commissars, Sinti and Roma, and anyone else the Nazis simply wanted eliminated.

While the extermination camps such as Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Sobibór are better remembered today, some historians argue, with much justification, that even the hell of the gas chambers cannot compete with the sheer cruelty, barbarity, and sadism of the Einsatzgruppen. So what exactly were these highly mobile death squads, what sort of men staffed them, and what evil crimes did they commit?

Many histories of the Einsatzgruppen begin with the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941—codenamed Operation Barbarossa—but its inception, in fact, predates this by several years.

An Einsatzkommando (or operational command) had been formed in early 1938 for operations in Austria following the Anschluss in March. In September of the same year, others, made up from members of the Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police, or SiPo), were established in the Sudetenland in anticipation of an invasion of Czechoslovakia, although the subsequent Munich Agreement rendered military action unnecessary.

Nevertheless, the Einsatzgruppen were still tasked with rounding up Czech communists and other political opponents, as well as seizing important government buildings for the Nazi regime.

The first major deployment of the Einsatzgruppen came with the invasion of Poland in September 1939. As German forces unleashed blitzkrieg, or lightning war, upon the Poles, the Einsatzgruppen followed closely behind the fighting men to carry out a decapitation operation.

Their objective was to round up and execute, or otherwise arrest, the Polish intelligentsia—politicians, university professors, teachers, doctors, lawyers, church leaders, and others members of the social elite—to remove the entirety of Poland’s leadership and thus reduce potential resistance to German occupation. This plan of systematic mass murder became known as the Intelligenzaktion (Intelligentsia Action).

For operations in Poland in 1939, a total of seven Einsatzgruppen were deployed, numbered I to VII, each consisting of up to 500 men recruited from the SS, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the police, and the Gestapo. Each Einsatzgruppe was divided into five Einsatzkommandos of around 100 men each.

Overall command of the Einsatzgruppen was given to SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Rudolf Werner Best, a trained lawyer and Gestapo chief who had notoriously established a registry of all Jews in Germany before the outbreak of the war. Best initially commanded 2,700 men, but the Einsatzgruppen would grow to 4,250 during the campaign in Poland—a small but deadly band of vicious murderers.

In readiness for the Intelligenzaktion, the Nazis had drawn up a detailed list of an incredible 61,000 people they wanted eliminated. This list was called the Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen (Special Prosecution Book-Poland), and it was compiled by the Zentralstelle IIP Polen (Central Unit IIP-Poland), a special department within the Gestapo, prior to the invasion of the country.

On August 22, 1939, mere days before the outbreak of war, Adolf Hitler made a speech in which he made his views about the coming campaign clear: “Kill without pity or mercy all men, women, and children of Polish descent or language. Only in this way can we obtain the living space [Lebensraum] we need.” Thus was the level of Nazi organization and preparation for the mass murder of tens of thousands of Poles before World War II in Europe had even begun.

The Einsatzgruppen ruthlessly carried out their orders from the outset. Within the first few months of the war, they either killed or sent to concentration camps to die virtually all the 61,000 on the Zentralstelle list. In addition, they murdered thousands of Romani and Sinti, mentally ill patients, and Jews, although the method for the systematic mass slaughter of the latter had not yet been determined.

In this bloody task, the Einsatzgruppen benefitted from the eager assistance of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz, a paramilitary unit staffed by ethnic Germans who had been living in Poland before the war. The killings were carried out by shooting, the bodies of the unfortunate victims being unsympathetically dumped into mass graves dug in forests and other remote areas.

One example of these mass murders was the operation named Intelligenzaktion Pommern, in which an estimated 23,000 Poles in the Województwo Pomorskie (Pomeranian Voivodeship, corresponding to a province in many other countries) were killed.

Here, Einsatzkommando 16, under the command of Gestapo officer Rudolf Tröger, and Regiment 6 of the SS-Wachsturmbann Eimann, led by SS-Sturmbannführer Kurt Eimann, perpetrated several massacres at Piasnica and Bydgoszcz (the Valley of Death). The killings in Piasnica are remembered as the first large-scale Nazi atrocity committed in Poland, where an estimated 10,000 to 12,000 Polish civilians are believed to have been murdered in 1939-1940.

It is, however, the actions of the Einsatzgruppen following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 for which they are most chillingly remembered.

This Vernichtungskrieg (war of annihilation) with the Soviets would be one of the most bitter military campaigns in history, during which some of World War II’s largest battles and worst atrocities took place, and the Einsatzgruppen would come to play a significant part in the resulting enormous death toll.

In the spring of 1941, several thousand men from the SS, police, and security services received orders to attend a police academy at Pretzsch, a small German town about 50 miles southwest of Berlin. None had been told exactly what their assignment would be, but many of them had served in the campaign in Poland and some could speak Russian. Most, therefore, would have had at least an idea why they were going there.

It is common today for us to think of criminals as unintelligent or war criminals as uneducated thugs. Many of those assembled at Pretzsch, however, were quite the opposite. Among them were lawyers and physicians, and a few even held doctorates in other fields. They were to form the backbone of a new Einsatzgruppe operation, one that would be bigger, deadlier, and more devastating than anything that came before.

The training at Pretzsch lasted for only three weeks, after which the men were officially told they would be operating in the Soviet Union. This time, four Einsatzgruppen would work behind the invading German forces, labeled Einsatzgruppe A to Einsatzgruppe D.

Einsatzgruppe A would be commanded by the 40-year-old SS-Brigadeführer Dr. Franz Walter Stahlecker; Einsatzgruppe B would be led by 46-year-old SS-Brigadeführer Arthur Nebe; Einsatzgruppe C under 49-year-old SS-Gruppenführer Dr. Otto Rasch; and Einsatzgruppe D under 34-year-old SS-Gruppenführer Professor Otto Ohlendorf. As before, each Einsatzgruppe would be subdivided into smaller units, including 16 Einsatzkommandos or Sonderkommandos.

Einsatzgruppe A was to be attached to Army Group North for operations in the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Einsatzgruppe B was to follow Army Group Center to operate in Byelorussia. Einsatzgruppe C likewise would follow Army Group South into northern and central Ukraine. Finally, Einsatzgruppe D would attach itself to the Eleventh Army to carry out its murderous work in Bessarabia, southern Ukraine, the Crimea, and the Caucasus.

The size of each Einsatzgruppe varied, the largest, Einsatzgruppe A, being almost 1,000 strong, while the smallest, Einsatzgruppe D, consisted of a mere 500 men. The recruitment of local auxiliaries, though, would later greatly boost numbers and thus wield even greater killing power.

Overall supervision of the Einsatzgruppen rested with SS-Gruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, director of the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), who in turn reported to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler.

To prevent friction between the Einsatzgruppen and the Wehrmacht (the German armed forces), Hitler had personally edited subparagraph B of the “Guidelines in Special Spheres re: Directive No. 21 (Operation Barbarossa)” on March 13, 1941, so that it now stated: “In the operations area of the Army, the Reichsführer-SS has been given special tasks on the orders of the Führer, in order to prepare the political administration. These tasks arise from the forthcoming final struggle of two opposing political systems. Within the framework of these tasks, the Reichsführer-SS acts independently and on his own responsibility.”

The senior officers of the Wehrmacht would have been under no illusion as to Hitler’s intentions toward the Jewish population of the Soviet Union. The killing of Jews and others was talked about using euphemisms, such as “special tasks” and “executive measures,” but the fact that the Führer had so often talked about the destruction of Judeo-Bolshevism (the Nazis believed there was a complete identity between communism and the alleged Jewish “world conspiracy”) in his speeches left little room for doubt.

While some officers and men of the Wehrmacht objected to the actions of the Einsatzgruppen during Barbarossa, many others would become complicit in the murders.

The invasion of the USSR began on June 22, 1941. As the juggernaut of the Wehrmacht rolled eastward, the Einsatzgruppen once again followed in its wake. Their targets were many, including Soviet political commissars, Jewish males aged 15 to 45, and any Soviet prisoners of war who were found to be Jewish.

Others, such as saboteurs and troublemakers, were also to be eliminated at the discretion of individual Einsatzgruppe commanders. It was also expected that local populations were likely to carry out spontaneous pogroms (violence against the Jews and their property), and so orders were given for these not to be interfered with—rather, they were to be secretly encouraged.

On June 23, the German Army occupied Kaunas in central Lithuania. Just behind it came an advance unit of Einsatzgruppe A, which immediately began to organize “spontaneous” pogroms against the Jews, who constituted 35,000 of the city’s 120,000 citizens.

Several days later, a German NCO became aware that a large gathering of local Lithuanians had appeared in the center of Kaunas. “I was informed by a driver in my unit that Jews were being beaten to death in a nearby square…. Upon hearing this, I went to the said square … [and] saw civilians, some in shirtsleeves … beating other civilians to death with iron bars.”

The civilians being beaten to death with iron bars were in fact Jews. The NCO continued: “When I reached the square, there were about 15 to 20 bodies lying there…. I saw Lithuanians take hold of these bodies by their hands and legs and drag them away. Afterwards, another group [of Jews] was herded and pushed onto the square, and without further ado, beaten to death.”

Unbeknownst to the German NCO, the killers were violent Lithuanian criminals whom the SS had earlier released from the local prison to make the pogrom look spontaneous. This was just one of many early examples of the Einsatzgruppen secretly inciting local populations to commit extreme acts of violence against local Jews.

The commander of Einsatzgruppe A, Franz Stahlecker, recruited 600 Lithuanian irregulars under the collaborator Algirdas Klimaitis to form an auxiliary police unit, and a further 200 under the command of a Dr. Zigonys. On June 25, these auxiliary policemen set fire to synagogues and houses occupied by Jews.

They then rounded up some 1,500 Jews and murdered all of them, and on succeeding nights, savagely slaughtered a further 2,300. The trigger-happy Lithuanians later attempted to justify the murders by claiming that the Jews had opened fire on German troops from house windows. These claims were, of course, a complete fabrication.

When Einsatzgruppe A reached Latvia’s capital Riga on July 1, Stahlecker similarly established a Sonderkommando made up of 300 Latvian auxiliary policemen under the command of Viktors Arajs. This Arajs Kommando, as it became known, was again tasked with setting up a spontaneous pogrom. As in Kaunas, violence erupted against the city’s Jewish population and those living in the surrounding area.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1941, Arajs embarked upon an orgy of mass killing of Jews. Twice a week, his Sonderkommando went to work, rounding up Jews and communists and taking them to the Bikernieki Forest, some four miles from Riga. Here, pits had been dug to hold the bodies of the victims after being shot. The killings were conducted in the darkness, the auxiliaries typically leaving their homes at 1 am and commencing their murderous activities several hours later.

By breakfast time, their latest victims would be dead, although when killing larger numbers, they would work into the early afternoon. To keep his men going through their difficult work, Arajs would ensure they received copious amounts of schnapps and food.

In late July 1941, Arajs stepped up his murderous activities when he commandeered Riga’s public buses. Filling these buses with his men, Arajs would drive out to the outlying villages, where they rounded up Jews and shot them. Village after village would be declared Judenfrei (free of Jews).

But it was not just Jews Arajs murdered while touring the countryside in his buses: the mentally ill also became victims of his unrestrained bloodlust.

To illustrate the horrific work of Stahlecker’s Einsatzgruppe A, the following is a report he wrote in 1941 before his work was even complete: “The systematic mopping-up of eastern territories embraced, in accordance with the basic orders, the complete removal, if possible, of Jewry. This goal has been substantially attained—with the exception of White Russia—as a result of the execution of 229,052 up to the present time. The remainder still left in the Baltic provinces is urgently required as labor, and is housed in ghettoes.”

Sonderkommando 1a, under the leadership of SS-Sturmbannführer Martin Sandberger, conducted similar operations in Estonia following the arrival of German combat troops in July and August 1941. Over half of Estonia’s Jews, who numbered around 4,500 before the war, had fled the country prior to the arrival of the Wehrmacht.

Nevertheless, Sandberger lost no time recruiting local militias to assist in the destruction of those who remained. By mid-October 1941, he reported to his superiors that “all male Jews over 16, with the exception of the appointed Jewish elders, were executed by the Estonian self-defence units under supervision of the Sonderkommando.”

At the same time as Stahlecker was ruthlessly murdering thousands in the Baltic States, SS-Brigadeführer Arthur Nebe’s Einsatzguppe B was likewise murdering its way through Byelorussia (modern-day Belarus). Upon the commencement of Operation Barbarossa, the Jewish population of the country was considerable, with an estimated 670,000 residing in the western side of the republic and 405,000 in the eastern side. Upon the commencement of Operation Barbarossa, the Jewish population of the country was considerable, with an estimated 800,000 residing in the republic.

Sonderkommando 7a arrived in Minsk on July 4, 1941, and Nebe instructed the unit to carry out a “reprisal action” against Jews in the city on the pretext that they had set fire to their homes after being told to leave to make them available to other Byelorussians.

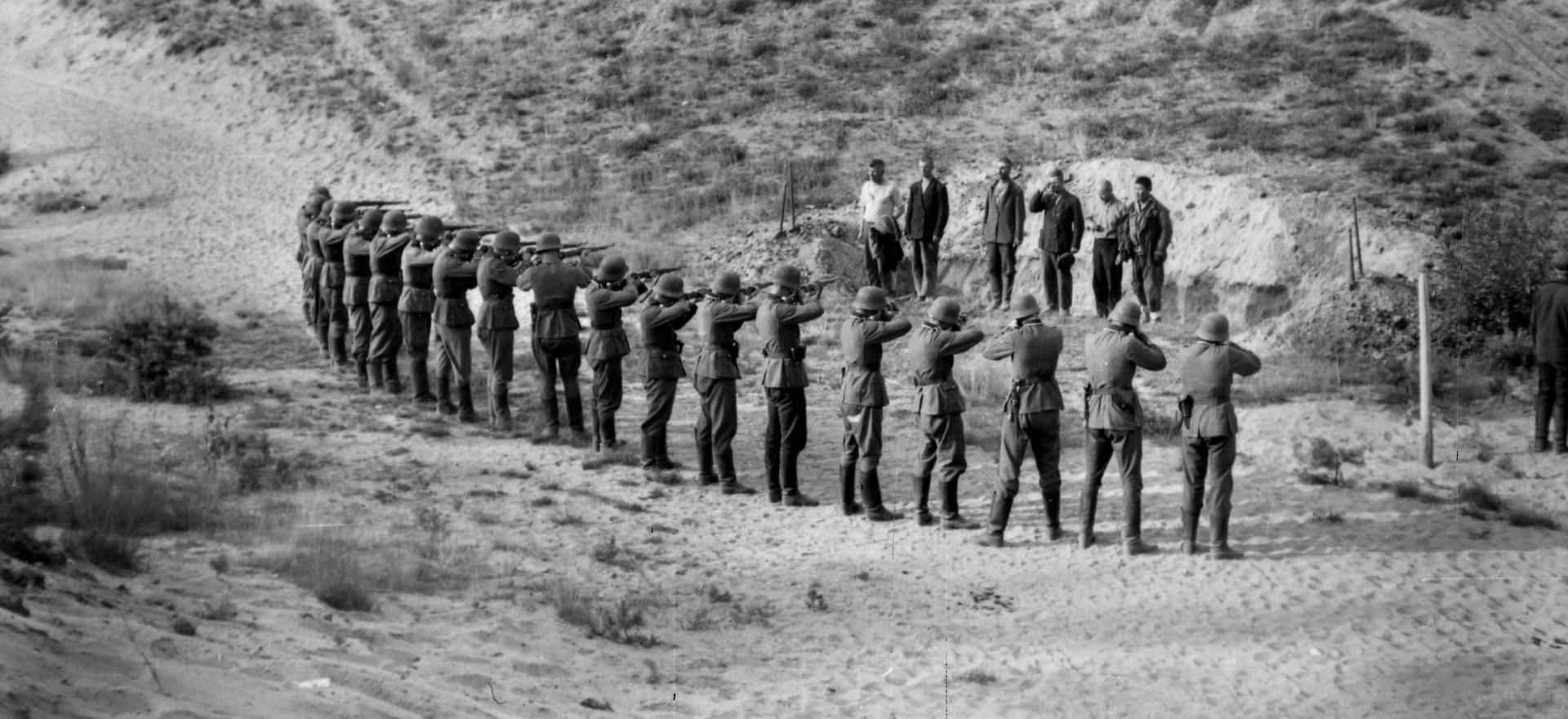

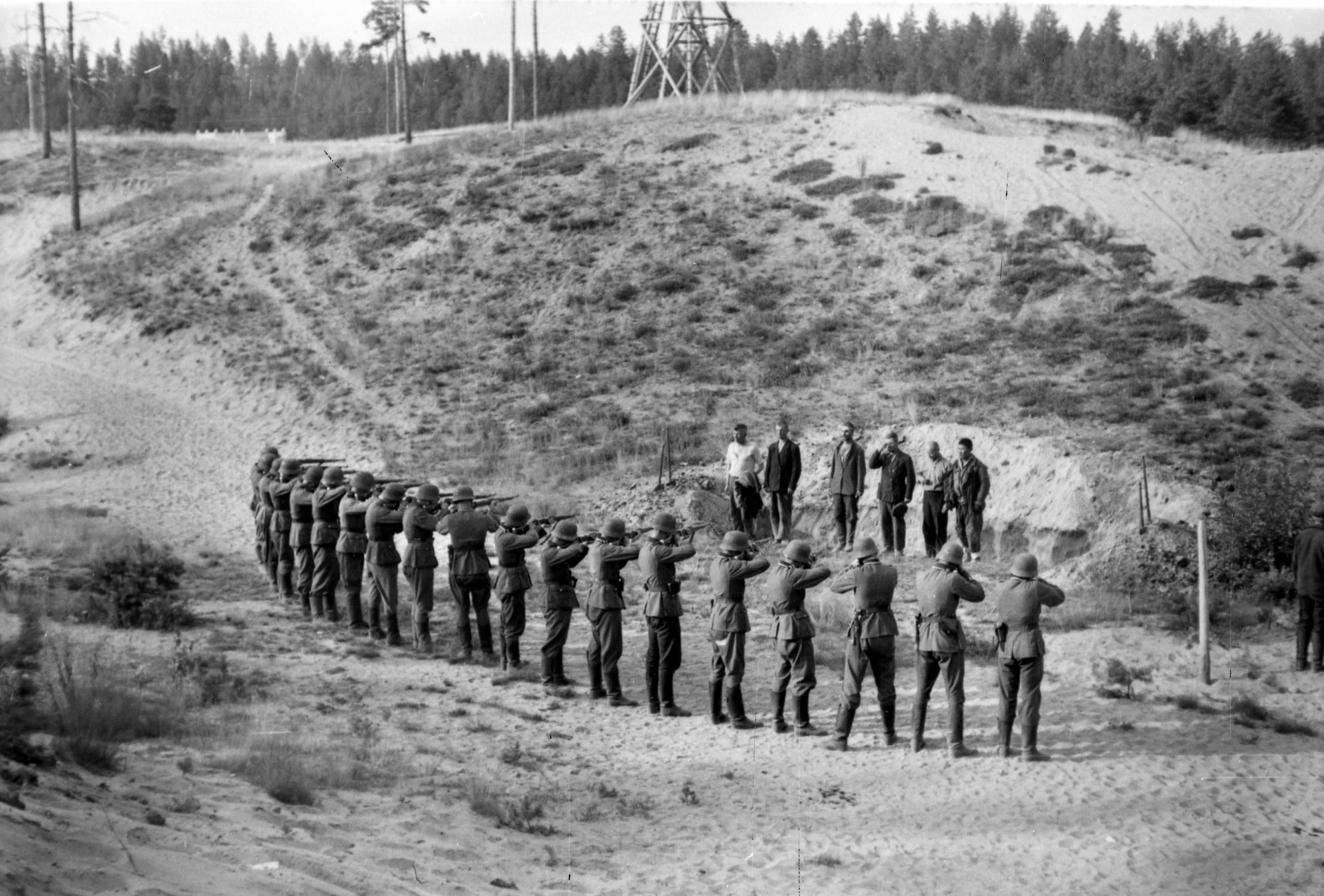

According to Walter Blume, the Sonderkommando’s commanding officer, “Ten men at a time would be brought to the execution place…. There was [an anti]tank ditch. The 10 men were put at that ditch and in a military manner were shot by rifles by the execution command, which included forty men. Three men always shot at a victim.…” Between 50 and 60 Jews were murdered during the so-called reprisal.

Blume’s unit moved on to Vitebsk, where Nebe again demanded the Jews be executed, and several days later the killings were duly carried out. Again, the victims were killed 10 at a time by shooting, their bodies falling into a pit where they were unceremoniously buried; around 80 Jewish men were killed there. There would, of course, be many similar acts of murder committed by Sonderkommando 7a and the others of Einsatzgruppe B in Byelorussia.

As in the Baltic States, Nebe recruited local men to carry out the killings under the supervision of his German units. On July 7, 1941, the Bielaruskaja Dapamoznaja Palicyja (Byelorussian Auxiliary Police) was established and became involved in the so-called “pacification actions” conducted in Byelorussia. These actions included the rounding up of Jews in Homel, Mozyrz, Kalinkowicze, and Korma, where the Germans found their assistance particularly helpful due to the fact they knew many of the local Jews on sight.

The Byelorussian Auxiliary Police were also deployed in guarding the Jewish ghettoes in Byelorussia, and when the killings began, they would escort the Jews to the killing sites. These mass executions took place from September to November 1941. According to an Einsatzgruppe B report, a total of 45,467 killings had been performed in Byelorussia by mid-November.

As the killing progressed, Nebe and his Einsatzgruppe B became unable to cope with the sheer number of Jews they were expected to execute. According to a report sent to Berlin in November 1941, “It is already at this time evident that this [the shooting] cannot be a possible solution of the Jewish problem.

“Although we succeeded, in particular in smaller towns and in villages … it is nevertheless observed repeatedly in larger cities that after such an execution all Jews have indeed disappeared, but when after a certain period of time a Kommando returns again, the number of Jews still found in the city always surpasses considerably the number of the executed Jews.”

Nevertheless, the mass killings by shooting continued throughout the remainder of 1941 and into 1942.

In late July 1941, the Germans had ordered the establishment of a ghetto in Minsk into which Jews from Slutsk, Dzerzhinsk, Cherven, Uzda, and other local villages were forced. A Judenrat (Jewish council) was set up, which had the responsibility of registering the entire local population of Jews and providing able-bodied men for labor.

For many, though, their time in the ghetto would be short, for on November 7, 1941, Einsatzgruppe B conducted an action to clear out large numbers of Jews to make room for others being transported to the ghetto from Germany.

Some 6,624 Jews were rounded up and taken by trucks to a former NKVD warehouse in the village of Tuchinka, where they were all murdered between 7 and 11 am by Sonderkommando 1b of Einsatzgruppe A. On July 20, 1942, another 5,000 were likewise shot at Tuchinka.

As already seen in Walter Mattner’s chilling letter to his wife, the Jews of Mogilev would also suffer the murderous wrath of Nebe’s men. The Germans occupied on July 26, 1941, after which they almost immediately registered all 6,437 Jews living in the city (the number had originally been higher but 2,000 Jews are thought to have perished during the city’s defense).

In mid-August, all of Mogilev’s Jews were ordered into a ghetto near the Jewish cemetery, but it proved too small, so a second ghetto was established in September on the opposite bank of the Dubrovenka River.

In September, Einsatzkommando 8 arrived in Mogilev, and on October 2-3, Police Battalion 322 of the Ordnungspolizei (ORPO), commanded by SS officer Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, moved into the new ghetto and carried out an action.

According to the unit’s war diary, “On October 2 … at 15:30, the 9th Company … together with HQ staff of the Higher SS and Police Leader ‘Center’ and the Ukrainian auxiliary police, carried out an action in the ghetto in Mogilev…. Sixty-five were shot trying to escape … [on] October 3 … Companies 7 and 9 … executed 2,208 male and female Jews in a forest outside of Mogilev.”

Two weeks later, the same unit carried out several further operations. Again, according to their own report, “On October 19, 1941, a large-scale operation against the Jews was carried out in Mogilev with the aid of the Police Regiment ‘Center.’ Three thousand seven hundred twenty six Jews of both sexes and all ages were liquidated by this action…. On October 23, 1941, to prevent further acts of sabotage and to combat the partisans, a further number of Jews from Mogilev and surrounding area, 239 of both sexes, were liquidated.”

Very few Jews survived the executions, but one who narrowly escaped death at Mogilev in October 1941 was a 14-year-old girl named Ida Arman: “They forced the people, mainly the women, to undress. The Gestapo men hit the naked women on their backsides with whips and laughed…. I started to cry, ‘Mother, they will shoot us! Mother, I don’t want to die!’ When they took us to the pits, it was crystal clear where they had taken us and why.

“Mother whispered in my ear, ‘Tell them you are not Jewish, that you’re Russian, and got into this truck by accident.’ She approached the SS men and started to explain: ‘This girl got into the truck by accident. She was living in our apartment and ended up in the ghetto by accident. She is not my daughter.’

“They put me aside. Mother tried to also save my little brother. My sister looked Jewish but my brother didn’t. Mother said no one knew whose son he was. The translator said to him, ‘Drop your pants.’ They pulled down his pants and started to laugh loudly. Like all Jewish males, my little brother was circumcised…. As for me, they threw me into a truck, took me back to Mogilev.

Units of SS-Gruppenführer Dr. Otto Rasch’s Einsatzgruppe C swept into northern and central Ukraine and almost immediately began rounding up Jews. In the middle of July, it entered Zhitomir, a town in the western part of Ukraine that had suffered immensely in the fighting unleashed by Barbarossa.

By the time the Germans entered the town, its population had already been reduced by more than half to around 40,000, 5,000 of which were Jewish. Sonderkommando 4a, under the command of Paul Blobel, spent several weeks executing communists, Jews, and those accused of being Soviet informants in and around the city. By the end of the month, the commando had murdered 2,531 people.

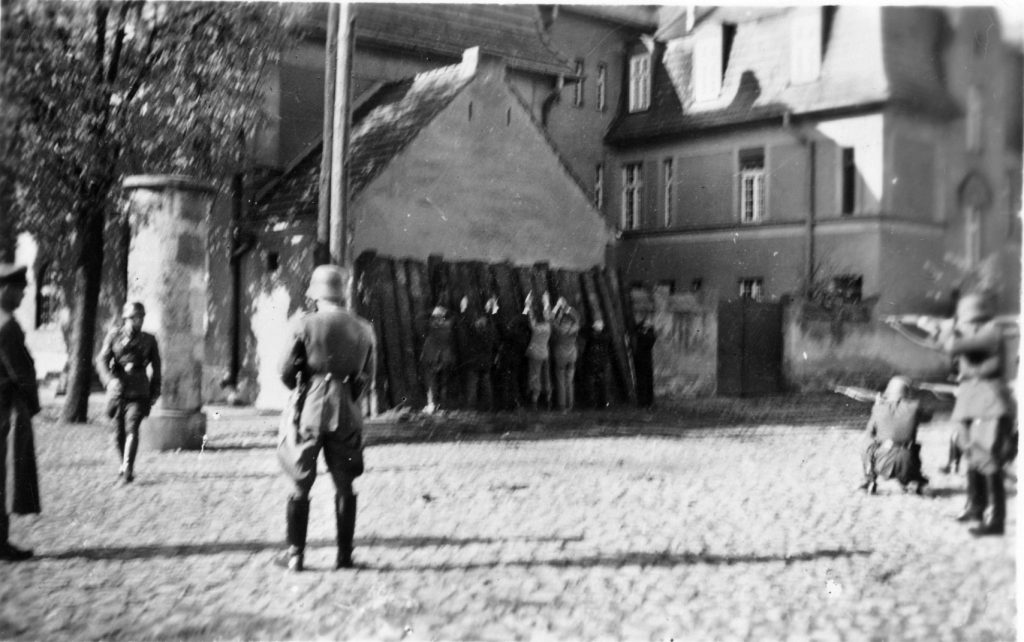

On August 7, 1941, Blobel had organized the public hanging of Wolf Kieper and Moshe Kagen, both Soviet judges who were Jewish, on the charge of murdering ethnic Germans. As part of this, 402 Jews were brought to the town square and ordered to watch the executions.

A large group of non-Jewish locals also attended, whom the Germans asked if they had any grievances they wanted addressed. This crowd gradually became angrier until they turned violently toward the Jews in the square, savagely beating them to death while Wehrmacht officers looked on. This, of course, was simply another “spontaneous” pogrom planned and initiated by the Einsatzgruppen.

Four or five days later, Sonderkommando 4a was ordered to Bila Tserkva to round up and dispose of the adult Jewish population of the town. After executing the adults, the Jewish children of the town were left locked in a school with a handful of Jewish women tasked with looking after them until they too were to be executed the next day.

The plight of these unfortunate children came to the attention of some soldiers of the Wehrmacht, who turned to several chaplains attached to their division for advice on what to do. In response, Father Ernst Tewes and the Pastor Gerhard Wilczek visited the school where they saw the hungry children in appalling conditions.

The chaplains, joined by others, protested the treatment of the children, and so Oberst Helmuth Groscurth, a staff officer, ordered their executions to be postponed. However, Walther von Reichenau, commander of the German Sixth Army, intervened and ordered the executions to be carried out as planned.

SS-Obersturmführer August Häfner later described the horrific killing of the children of Bila Tserkva: “I went out to the woods alone. The Wehrmacht had already dug a grave. There, children were brought in a tractor (drawn wagon). I had nothing to do with the technical procedure. The Ukrainians [Ukräinische Hilfspolizei/Ukrainian Auxiliary Police] were standing around, trembling. The children were taken down from the tractor. They were lined up along the top of the grave and shot so that they fell into it…. The wailing was indescribable…. Many were hit four or five times before they died.”

It would be for his actions within the area of operations of Einsatzgruppe C that Unterstürmfuhrer Max Täubner of the 1st SS Infantry Brigade, along with four other co-defendants, would ironically be court-martialed for killing Jews. Täubner’s unit, a Werkstattzug (workshop platoon), had arrived in Novograd Volytnsky, located some 60 miles west of Zhitomir, on September 17, 1941.

Here, Täubner met the town’s mayor who complained he had more than 300 Jews locked up in the local prison. The mayor wanted to be rid of the Jews and asked Täubner if they could be shot. Täubner told the mayor that his platoon would perform the executions. The Ukrainian auxiliaries dug a pit nearby, after which the SS men murdered the 319 Jews.

One of the SS men from the Werkstattzug recalled the killings: “The victims were shot by the firing squad with carbines, mostly by shots in the back of the head, from a distance of one meter on my command…. Before every salvo, Täubner gave me the order—‘Get set, fire!’ I just relayed Täubner’s command.…”

“Meanwhile, Rottenführer (foreman) Abraham shot the children with a pistol. There were about five of them. These were children whom I would think were aged between two and six years…. The way Abraham killed the children was brutal. He got hold of some of the children by the hair, lifted them up from the ground, shot them through the back of their heads and then threw them into the grave.”

Täubner’s sickening lust to kill Jews did not end there. His platoon next went to a village called Sholokovo, where he murdered 191 Jewish men, women, and children on October 17. The Werkstattzug then moved on to Aleksandriya, where Täubner allegedly heard a rumor that Jews planned to poison the local water supply. Again, pits were dug, and the brutal killing began as before.

The Unterstürmführer struck his victims in the face with a whip, took photographs of the killings, and even spontaneously played an accordion as the SS men pulled the triggers on their rifles.

It may seem unbelievable today, but Täubner’s unauthorized killing of Jews led to him being arrested and put on trial. During the trial, it was stated, “The accused shall not be punished because of the actions against the Jews as such. The Jews have to be exterminated and none of the Jews that were killed is any great loss.

“Although the accused should have recognized that the extermination of the Jews was the duty of Kommandos which have been set up especially for this purpose, he should be excused for considering himself to have the authority to take part in the extermination of Jewry himself. Real hatred of the Jews was the driving motivation for the accused. In the process, he let himself be drawn into committing cruel actions in Aleksandriya which are unworthy of a German man and an SS officer.”

The court sentenced Täubner to imprisonment, but he would be released after two years following a pardon from Himmler. It is unlikely the murder of Jews was the real issue for the SS; rather, it was the need to ensure discipline among the frontline units, as Täubner had acted without orders.

Einsatzgruppe C would be involved in many other murders, including the particularly infamous massacre at Babi Yar. By December 1942, this unit alone had killed almost 120,000 Jews.

The story of Otto Ohlendorf’s Einsatzgruppe D is another similar and hideous tale of brutal murder. On August 16, 1941, the Germans occupied Nikolayev in southern Ukraine, where they immediately established a Judenrat and gave orders that all Jews in the city be registered. In 1939, prior to the outbreak of war, the Jewish population of the city stood at 25,280.

Many more arrived after the invasion of Poland, having fled advancing German forces. Those Jews now trapped in Nikolayev were ordered to sew a Star of David patch on their clothes and were set to work doing manual labor. A ghetto was also set up in Nikolayev at the end of August or in early September, 1941.

It would, however, only be a matter of days before the men of Einsatzgruppe D began their murderous work. In late August 1941, Sonderkommando 11a shot 230 Jews for failing to register, or for some other perceived disobedience of German authority.

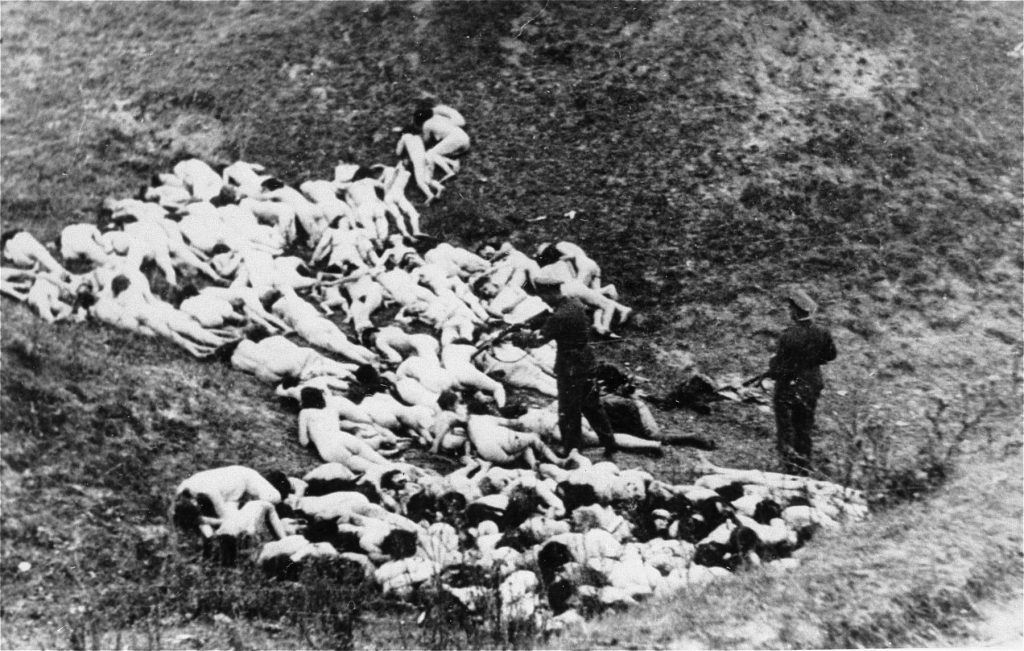

A much larger massacre occurred later. On September 14, all Jews were ordered to assemble at the Jewish cemetery in the Slobodka district of the city. Here, they were told they were to be resettled, and, from the 16th to the 18th, the Jews were rounded up. Three days later, they were loaded onto trucks and taken to the Voskresenskoye Ravine, located about six miles east of Nikolayev.

The victims were herded into the ravine in groups of 35 to 40, where they were ordered to strip naked before being shot. The units involved in the massacre included Sonderkommando 10a, Sonderkommando 11a, Einsatzkommando 12, and the 9th Reserve Police Battalion (attached to Einsatzgruppe D). In all, they murdered around 5,000 people.

Following the massacre at Voskresenskoye, the Germans conducted a roundup of Jews who had managed to escape the executions. It is not known how many were caught, but those who were apprehended were transported to Temvod, a suburb of Nikolayev. Here, they were similarly shot and buried in pits near the bank of the Ingul River in October 1941 by members of Sonderkommando 11a and Einsatzkommando 12.

One witness to the work carried out by Einsatzgruppe D was Wehrmacht Oberleutnant Erwin Bingel. He was later taken as a prisoner of war, and during his time in captivity, he made the following testimony of the killing of Jews in Vinnitsa in September 1941: “In the morning at 10:15, wild shooting and terrible human cries reached our ears. At first, I failed to grasp what was taking place, but when I approached the window from which I had a broad view over the whole of the town park, the following spectacle unfolded before my eyes and those of my men, who, alerted by the tumult, had meanwhile gathered in my room.

“Ukrainian militia on horseback, armed with pistols, rifles, and long straight cavalry swords, were riding wildly inside and around the town park. As far as we could make out, they were driving people along before their horses—men, women, and children. A shower of bullets was then fired at this human mass. Those not hit outright were struck down with the swords.

“Like some ghostly apparition, this horde of Ukrainians, let loose and commanded by SS officers, trampled savagely over human bodies, ruthlessly killing innocent children, mothers, and old people whose only crime was that they had escaped the great mass murder, so as eventually to be shot or beaten to death like wild animals.”

Another example of Einsatzgruppe D’s work can be seen in the massacre of Jews in Simferopol in the Crimea. The Germans had occupied the city on November 1, 1941, upon which they ordered all Jews to wear white armbands marked with the Star of David on both arms. Again, a Judenrat was appointed, and all Jews in the city were registered. Around 12,000 Jews were listed on the register, and many were put to work doing physical labor.

As at Nikolayev, on December 6, the Jews of Simferopol were ordered to assemble at several locations across the city, where they were told they would be resettled. Three days later, 2,500 Krymchaks (Crimean ethnic Jews) were loaded onto trucks and driven down the Simferopol-Feodosiya Road. After traveling for about six miles, they were told to get out and were shot, their bodies dumped into an antitank ditch.

Between December 11 and 13, 9,500 Ashkenazi Jews were loaded into caravans and onto trucks and taken to the site of the December 6 murders. Here, they were forced to strip before being shot and buried in the antitank ditch. These latest murders were performed by Sonderkommando 10b, Sonderkommando 11a, Sonderkommando 11b, and the 683rd Motorized Military Police Detachment.

These killings were as brutal as those carried out before. Men and women were lined up in groups of 100 to 300 on the edge of the ditch before being shot by machine guns. Once their bodies fell into the ditch, they were covered with a layer of earth before the next batch of victims was likewise put to death. Small children are said to have been murdered in front of their parents when poison was smeared under their noses or on their lips.

The Roma (or gypsy) people of Simferopol were also murdered during the Simferopol-Feodosiya Road massacre.

Perhaps one of the largest atrocities committed by the Täubner were the massacres at Babi Yar, a ravine on the outskirts of Kiev, in late September 1941. The Germans had occupied Kiev on September 19, 1941, but the Soviets were able to bomb some of the buildings that had been taken over by the Wehrmacht. In retaliation, the Nazis decided to murder all the Jews in the city.

To round up the Jews, the Germans posted the following notice around the city in Russian and Ukrainian: “Kikes [an ethnic slur for Jews] of the city of Kiev and vicinity! On Monday, September 29, you are to appear by 7 am with your possessions, money, documents, valuables, and warm clothing at Dorogozhitshaya Street, next to the Jewish cemetery. Failure to appear is punishable by death.”

Fritz Hoefer, a local truck driver forced to assist the Germans, was witness to what happened. He said, “Naked Jews were led to a ravine about 150 meters long, 30 meters wide, and 15 meters deep. The Jews went down into the ravine through two or three narrow paths. When they got closer to the edge of the ravine, members of the Schutzpolizei (Germans) grabbed them and made them lie down over the corpses of the Jews who had already been shot…. It took no time.

“The corpses were carefully laid down in rows. As soon as a Jew lay down, a Schutzpolizist came along with a sub-machine gun and shot him in the back of the head. The Jews who descended into the ravine were so frightened by this terrible scene that they completely lost their will.”

Hoefer recalled that only two men actually did the shooting, one starting at one end of the ravine and a second at the other. They would then work their way toward each other, shooting their victims as they went.

Hoefer continued, “I saw dead bodies at the bottom laid across in three rows, each of which was approximately 60 meters long; I could not see how many layers were there. It was beyond my comprehension to see bodies twitching in convulsions and covered with blood, so I could not make sense of the details.

“Apart from the two machine gunners, there were two other members of the Schutzpolizei standing near each passage into the ravine…. They made each victim lie down on the corpses, so that the machine gunner could shoot while he walked by. When victims descended into the ravine and saw this terrible scene at the last moment, they let out a cry of terror. But they were grabbed by the waiting Schutzpolizei right away and hurled down onto the others.”

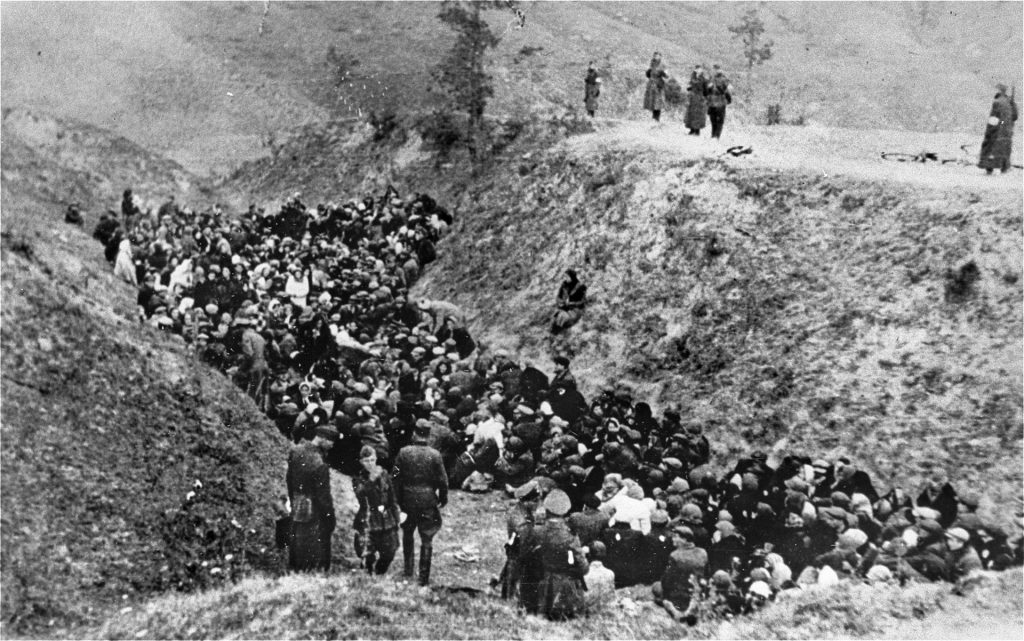

Another witness to the murders at Babi Yar was Dina Pronicheva, herself a Jew who, incredibly, managed to survive the shootings: “When we neared Babi Yar, shooting and inhuman cries could be heard…. When we entered the gate, we were ordered to hand over documents and valuables, and to take off our clothes. One German approached my mother and tore her gold ring off her finger…. All [the Jews] were being taken to an open pit where submachine gunners shot them. Then another group was brought….

“With my own eyes I saw this horror…. [A] policeman ordered me to strip and pushed me to a precipice…. But before the shots resounded, apparently out of fear, I fell into the pit. I fell on the [bodies] of those already murdered…. The shooting was continuing and people kept falling…. Suddenly, all became quiet. It was getting dark…. I felt we were being covered with earth…. When it became dark and silent, literally the silence of death, I opened my eyes and threw the sand off me…. I said to myself: ‘Dina, stand up. Get away!’ So I stood up and ran.”

Some 33,771 Jews were murdered at Babi Yar over the two-day period of September 29-30, 1941. Those carrying out the killings were men of Blobel’s Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C. Due to the large numbers being killed in only two days, the men of the Sonderkommando failed to ensure everyone in the pit had died before proceeding to shoot the next batch. This allowed Dina Pronicheva and a handful of others to survive and later testify as to the horrors they endured, a rare occurrence in the history of Einsatzgruppen murders.

Thousands of Jews were murdered on November 30 and December 8-9, 1941 in the Rumbula Forest, five miles southeast of Riga along the Riga-Dvinsk railway and the Riga-Salaspils road. Although second only to the better known Babi Yar massacre, the Rumbula killings have received relatively little attention from historians. This is despite the fact that some 26,000 Jews (estimates vary) were shot by German killing squads and their Latvian auxiliaries at Rumbula.

In mid-August 1941, all Jews in Riga had been ordered into a ghetto that had been established in the Moscow quarter of the city. Here 15,738 women, 8,212 men, and 5,652 children were eventually interned. Meanwhile, Himmler was planning to dispose of the Latvian Jews to make room for Jews being transported to the ghetto from Germany and Austria.

The Reichsführer-SS brought in SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln to organize and carry out the killing operation. Jeckeln, a veteran of World War I and a long-standing Nazi Party member, had previously served with the Einsatzgruppen in Ukraine and had been responsible for the massacres at Babi Yar and Kamianets-Podilskyi (August 27-29, 1941). He was thus ruthlessly qualified for the job.

On the first day of the murders, Jeckeln ordered the ghetto to be cordoned off and the Jewish work detachment, which was to be temporarily spared death, marched out. The remaining Jewish inhabitants

of the ghetto were told they were to be resettled farther to the east and to be ready to move.

The blue buses of the Arajs Kommando were then driven up to the ghetto entrance in readiness for the action. About 12 miles away, in the Rumbula Forest, execution pits had already been dug by Russian POWs. Jeckeln had chosen the site due to the sandy soil, which was much easier to dig in than the swampy ground Riga had been built upon. The Jews were then force-marched to Rumbula, with many dying during the harsh journey.

Frida Michelson, a Latvian Jew who would miraculously survive the massacre, recalled the horror of the march to the killing pits: “The columns of people were moving on and on, sometimes at a half run, marching, trotting, without end. There one, there another, would fall and they would walk right over them, constantly being urged on by the policemen, ‘Faster, faster,’ with their whips and rifle butts…. Corpses were scattered all over, rivulets of blood still oozing from the lifeless bodies. They were mostly old people, pregnant women, children, handicapped, all those who could not keep up with the inhuman tempo of the march.”

After arriving at Rumbula, groups of 50 were sent into the forest and forced to run a gauntlet made up of hundreds of auxiliaries of the Arajs Kommando. The victims were then ordered to undress and made to run to the killing pits. As they descended into the pits, they were positioned so they would fall on top of those killed before them, in order to stack as many bodies into the pit as possible.

The killers then opened fire, using Russian-made submachine guns. The process was then repeated until, by the end of the day, some 13,000 Jews had been murdered.

The efficient system of killing employed at Rumbula—also employed at Babi Yar and Kamianets-Podilskyi—had been devised and refined by Jeckeln and thus became known as the “Jeckeln System.”

It was ruthless but simple: Jewish populations earmarked for death were assembled with the promise of resettlement and then marched or transported to their place of execution. Once they arrived, they were stripped of their valuables and clothes, which would be recycled by the Germans, and forced to lie face down in the bottom of the killing pits. The shooting then took place and the procedure repeated for successive groups of victims.

A week later, on December 8, Jeckeln repeated the entire process, liquidating the remaining 10,000 Jews of the Riga Ghetto. A number of German Jews transported to Riga from Berlin were also executed at Rumbula on the first day, but Jeckeln had killed them without authorization from Himmler. The former, incredibly, found himself being disciplined by the latter for their murder.

The preferred method—although methods varied between individual Einsatzkommandos and Sonderkommandos—of many of the killers of the Einsatzgruppen for shooting their victims was known as Genickschuss, the shooting of a person through the back or nape of their neck.

Jeckeln and others also employed Sardinenpackung, which, in Jeckeln’s own words, involved stacking the bodies of those executed “like sardines” neatly into the killing pits. It was a horrendously brutal and cruel system that worked extremely well, but the killing of unarmed men, women, and children in cold blood took its toll on the executioners.

On August 15, 1941, Himmler personally attended a mass execution near Minsk carried out by Einsatzkommando 8 of Einsatzgruppe B and Police Battalion 9. The victims were brought up to the execution pits in trucks, where they were shot.

SS officer Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski later recalled Himmler’s reaction when the killings began: “Himmler was extremely nervous. He couldn’t stand still. His face was white as cheese, his eyes wild, and with each burst of gunfire he always looked to the ground.” During the execution, two women were repeatedly hit but not killed outright, at which point Himmler allegedly screamed, ‘Don’t torture these women! Fire! Hurry up and kill them!’”

Once the killings had ended, Bach-Zelewski claimed he said to Himmler, “Look at the men [the Germans], how deeply shaken they are! Such men are finished for the rest of their lives! What kind of followers are we creating? Either neurotics or brutes!”

A more humane way of killing was sought—not for the victims but for the killers. The transition from bullets to gas began with gas vans, previously used to euthanize mentally ill patients, being made available. These vans proved unpopular with the Einsatzgruppen, as the removal of the dead from the van for burial was a difficult and a particularly harrowing process.

Nevertheless, experiments using gas to kill continued and would eventually evolve into the main method of killing in the extermination camps. As the Operation Reinhard camps (Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka) and Auschwitz became the main killing sites, the Einsatzgruppen switched to fighting partisans. Their brutality, however, never abated.

These are only a handful of the many, many mass murders carried out by the Einsatzgruppen in eastern Europe during World War II. A second sweep of the region would commence at the end of 1941, which lasted well into the summer of the following year. The commanders of each Einsatzgruppe would also change, while the Germans relied increasingly more on their locally raised auxiliaries to do the actual killings.

Estimates of Jews killed vary, sometimes considerably, depending on the source, but the following statistics were compiled from the Jäger (SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger, December 1, 1941) and Stahlecker reports: Einsatzgruppe A, 363,337 killed; Einsatzgruppe B, 134,000; Einsatzgruppe C, 118,341; Einsatzgruppe D, 91,728; and higher SS and police leaders and staff, 445,325. There were, of course, many non-Jewish victims in addition to this number, raising the overall figure to well over a staggering two million.

Following the defeat of Germany, the Allies tried 24 senior Einsatzgruppen leaders for war crimes and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials in 1947-1048. A total of 14 were sentenced to death, two given life sentences, while the remainder received lesser sentences.

Only four of the executions were actually carried out, though, although an additional four Einsatzgruppen leaders were executed by other nations.

Franz Stahlecker was killed in combat on March 23, 1942, by Soviet partisans near Krasnogvardeysk in Russia. Arthur Nebe was implicated in the July 20, 1944, plot against Hitler and hanged in Plötzensee Prison, Berlin, on March 21, 1945. Otto Rasch, although initially put on trial at Nuremberg, had the case against him dropped after it was claimed he was suffering from Parkinson’s disease and dementia, and he died on November 1, 1948.

Otto Ohlendorf was one of those sentenced to death at Nuremberg, his execution being carried out at Landsberg Prison in Bavaria on June 8, 1951.

Thirty-four years after the war, Viktors Arajs, having initially escaped prosecution, was found guilty by the State Court of Hamburg on December 21, 1979, for the mass murder of Jews at Rumbula. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and died in 1988.

Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski agreed to testify against former colleagues in exchange for not facing trial at Nuremberg, although he was later tried and convicted of killing political opponents of the Nazi regime in the 1930s. He received a prison sentence and died in a Munich prison on March 8, 1972.

Friedrich Jeckeln fell into the hands of the Soviets, who tried him at Riga in January and February 1946. He was found guilty and hanged in the city in front of a crowd of 4,000 onlookers on February 3, 1946.

Despite their horrific, unforgivable crimes, the vast majority of Einsatzgruppen murderers were never charged nor brought before a court to answer for their wartime actions. The West German Central Prosecution Office of Nazi War Criminals did later bring charges against 100 former Einsatzgruppen personnel, but the sad reality was most of them escaped justice and lived out the rest of their lives as free men. Conversely, the bodies of their victims remain buried in unmarked graves littered across Eastern Europe.