By Sam McGowan

The subtitle for this book, How Ordinary Soldiers Defeated Hitler, pretty well sums up the authors’ objectives in describing the Normandy Campaign through the eyes of the men who did the actual fighting. In the minds of most Americans, “Normandy” means the D-day landings of June 6, 1944, and that once the troops had established a beachhead, it was simply a matter of pouring in enough men and equipment to overwhelm the Germans. In Normandy: The Real Story (Presidio Press, New York, 2004, 363 pp., $16.95, hardcover), however, authors Denis and Shelagh Whitaker and Terry Kopp reveal that this is not the way it happened. The success of the campaign was never guaranteed, and if Hitler had not elected to keep a large army at the Pas de Calais, defending against an Allied army that did not exist, instead of reinforcing Normandy, the outcome may very well have been different.

In spite of the successful counterintelligence coup, the Allied forces were literally stuck on the beaches for six weeks before they were able to break out. It was then that the Normandy Campaign really began. Once the first Allied troops managed to fight their way off the beaches, they found themselves in the tangled bocage, a network of centuries-old hedgerows that served as a natural fortification for the German defenders.

This book is the story of the Normandy Campaign, from General Omar Bradley’s successful departure from the bocage country to take the high ground at St. Lo, through the attempts to close the Falaise Gap.

This book is the story of the Normandy Campaign, from General Omar Bradley’s successful departure from the bocage country to take the high ground at St. Lo, through the attempts to close the Falaise Gap.

The authors are well suited to tell this story. The late Denis Whitaker was a battalion commander in the Canadian forces and very familiar with the campaign, while his wife is a noted journalist. Their collaborator, Terry Kopp, is a noted military historian. Their story is based, to a large degree, on personal accounts with input from officers and soldiers representative of all of the participating combatants—American, British, Canadian, French, German, and Polish. While the bulk of the narrative is related to the armored and infantry troops who were fighting the battles, the tactical air forces also receive their due, particularly the American P-47 Thunderbolt and British Typhoon pilots who became so crucial to the success of the Allied campaign.

It is in the area of American tactical air power that the authors make a minor mistake. Throughout their narrative they refer to “Queseda’s 9th Tactical Air Force,” when in fact, there was no such thing. Major General Elwood “Pete” Queseda commanded IX Tactical Air Command, one of several commands under the U.S. Ninth Air Force, commanded initially by Lieutenant General Louis Brereton, then by Lt. Gen. Hoyt Vanderberg after August 8, 1944. There was a British II Tactical Air Force, which was the equivalent of the American Ninth Air Force of which IX Tactical Air Command was a part. This is not exactly a minor error, especially since the main goal of the book is to set the record straight regarding the way the Allies actually fought the war in Normandy as opposed to the traditional historical view.

In the final chapter, historian Kopp takes on the views of U.S. Army historian S.L.A. Marshall regarding the fighting ability of the American soldier. Marshall is a famed military historian who claimed that in the typical U.S. Army unit, the bulk of the fighting was carried out by a relatively small handful of particularly aggressive soldiers, and that most troops never even fired their weapons in combat.

Kopp disagrees with the view held by many professional soldiers and historians who have used Marshall’s reports as a basis for the belief that the citizen/soldier was poorly trained and motivated and a far less effective soldier when compared to the Germans. Kopp also challenges the theories that the war in Europe was won primarily by the application of artillery and air power. Yet, throughout the preceding chapters there is one account after another of how single officers and soldiers performed particularly heroic acts that inspired their fellows, who were often cowering behind hedgerows or in their slit trenches, to get up and capture an objective.

Nor is there any shortage of accounts of how Allied fighter-bombers wreaked havoc on German columns as they attempted to move along the Norman roads and country lanes. The Germans were so fearful of the fighter-bombers that they made their troop movements at night.

Artillery, whether mounted on a tank chassis or arranged in batteries, is revealed as the main Allied killing machine that allowed the infantry and armored columns to advance.

Incompetence at high levels was present on both sides and seemed to be equally distributed among the Americans, British, Canadians, and French. The Germans had their own problems, not the least of which was Hitler’s insistence that the campaign be under his personal command. The hesitant Bradley halted General George Patton’s rapid encirclement of the German armies and redirected him toward the Seine.

The authors maintain that Bradley lacked the capability to command a large army in 1944. Similarly, Eisenhower was afraid to take the necessary risks that might have allowed an Allied victory that summer. One American commander was so incompetent that his aide was instructed to countermand every order the man issued and to be prepared to shoot him if he got too far out of hand.

While there were horror stories, there were also unexpected triumphs. The U.S. 90th Division, a National Guard unit made up of Okies and Texans, had the reputation as the worst division in the entire U.S. Army and perhaps the worst in all of Europe. When Brig. Gen. Raymond McLain, an Oklahoma banker and National Guard veteran, took over the division, the men of the 90th began to live up to their World War I nickname “Tough Hombres.”

In spite of incompetence on the part of the commanders and disasters such as “friendly” bombing that occurred not once, but at least three times—in one instance killing the commander of the U.S. Army Ground Forces, Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair—the Allied troops managed to move forward and defeat the Germans. Their success came about thanks in large measure to the efforts of commanders at the division level and below. In many instances, military triumphs occurred because of the efforts of individual officers and soldiers. It is their story that the authors set out to tell. Their efforts have produced a truly worthwhile book.

Rising ’44: The Battle for Warsaw by Norman Davis, Viking/Penguin, New York, 2004, 752 pp., $32.95, hardcover.

Rising ’44: The Battle for Warsaw by Norman Davis, Viking/Penguin, New York, 2004, 752 pp., $32.95, hardcover.

The summer of 1944 signaled the beginning of the end for Hitler’s Third Reich and with it the increasing flames of hope for the countries that had been under the German yoke for nearly half a decade.

Although German oppression was severe in all of the occupied countries, Poles suffered more than most, due to their “subhuman” status in the eyes of the Nazis. Polish Jews were subjected to exceptionally harsh treatment—more than 300,000 were sent to concentration camps from Warsaw alone—while thousands more died of starvation and sickness in the Warsaw Ghetto the Nazis created to separate them from Gentiles.

The Jews of Warsaw were practically wiped out when they staged an armed uprising in 1943; German troops killed thousands and turned the Ghetto into rubble. Jews were just one of the objects of Nazi oppression and persecution. The Polish people themselves were subjected to genetic cleansing, as the malformed, the feeble-minded, the infirm, and the elderly were rounded up and sent off to concentration camps and extermination.

Even as the Soviet Army advanced closer and closer to the former Polish capital of Warsaw, Poles were fearful. As much as they hated and feared the Germans, the Soviets were hardly thought of as friends. Before the war, Polish leaders considered the Germans as but one of two major potential enemies, and with good reason, as the events of 1939 made clear.

Even as Germans occupied western Poland, their Soviet allies entered the country from the east, leaving a trail of oppression in their wake. Historical records indicate that Soviet atrocities against Poles were even worse than those of the Germans during the months when the country was parceled off between two equally vicious occupiers. In 1943, Germany revealed the discovery of mass graves in the Katyn Forest, graves that contained the bodies of some 4,300 Polish officers who had been shot by the Soviets during their occupation of eastern Poland.

Interestingly, although American political leaders knew that the Soviets were responsible for the deaths, they publicly blamed the deaths on the Nazis to protect the reputation of Stalin and the Soviet Union, who were their allies. It was with good reason that Poles were less than enthusiastic about the approach of the Soviet “liberators” as they advanced closer and closer to the outskirts of Warsaw.

Once the Soviets had advanced into Warsaw, it would be impossible for the Polish people to exercise their own sovereignty. Soviet forces would implement their own form of government that would answer directly to Moscow. Still, an uprising of resistance forces at the backs of the Germans would only help the Soviet advance, so the Polish resistance elected to rise in the hope that Moscow would look upon their efforts with favor. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a forlorn hope.

Thousands of young Polish men had managed to make their way out of the country when it fell to join Free Polish units organized under the British. Thousands more joined the Polish resistance, and as the Soviets approached Warsaw, they awaited the decision to rise up against the German occupiers and open the way for the Soviet advance into the city. By late July, Soviet forces had pushed the Germans until their backs were on the Vistula River, which ran through the city. Realizing it was now or never, the resistance soldiers of the Polish Home Army commenced their rising.

The events of August-October 1944 are some of the most tragic of the war. Instead of attacking from the front while the Polish resistance attacked the German rear, the Soviets held up their advance, leaving the Poles to their own devices. The Soviets stood by and watched as the Germans destroyed the Poles. German SS units set out to put down the rising, dashing the hopes of the Poles as the Soviets elected not to come to their assistance. Although Allied airmen—particularly British and Poles—mounted a massive airlift of supplies to the resistance fighters, no reinforcements were sent to their aid. The resupply missions were very costly in men and aircraft, and not all of the losses were to German flak and fighters. Soviet antiaircraft and fighters were turned on the transports, most of which were American-built Liberators assigned to British and Polish RAF squadrons operating out of Italy.

Even though supplies and agents could be delivered by air, significant reinforcements were another story. The Free Polish forces included a large contingent of paratroopers, but the logistics of moving them from Britain to Warsaw were impossible. While the Poles were rising against the Germans in Warsaw, the 1st Polish Armored Division was fighting with British and Canadian troops in Normandy.

Polish paratroopers were sent into Holland with British Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery’s ill-fated Operation Market Garden at the same time their brothers were battling the Germans in Warsaw, most meeting a similar fate. At Warsaw, the Soviets simply waited on the east bank of the Vistula while the Germans slaughtered the resistance fighters.

Norman Davies has done an excellent job of telling the story of the people of Warsaw. An expert on Polish history, he sets the stage for the rising in chapters devoted to the political situation that led to the failure of the Soviets to come to the aid of the Polish resistance. The section on the rising itself contains numerous accounts by participants, including British and Polish airmen as well as resistance survivors. The final chapters describe the aftermath of the resistance capitulation to the Germans, who, perhaps surprisingly, generally made good on their agreements with the resistance leaders.

Rising ’44: The Battle for Warsaw is an important book about an important event of history and a must-read for the serious student of World War II.

You’re Stomping on My Cloak and Dagger by Roger Hall, Blue Jacket Books, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2004, 219 pp., $20.00 (estimated), hardcover.

You’re Stomping on My Cloak and Dagger by Roger Hall, Blue Jacket Books, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2004, 219 pp., $20.00 (estimated), hardcover.

This is the personal memoir of Roger Wolcott Hall, an Annapolis, Md., native and son of a career naval officer. Like many other young, single officers, Hall volunteered for duty with a highly secretive organization that he knew nothing about as a means of getting out of a dead-end assignment at a base he did not like and away from a commander he detested.

A draftee who had received his commission through OCS, Hall was at an obscure base in Louisiana training Transportation Corps draftees when he was invited to volunteer for “hazardous overseas duty” with an organization “similar to commando” operations. In his memoir, Hall describes his three years with General “Wild Bill” Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services, from the time he first arrived at OSS headquarters in Washington, D.C., until he was separated from the Army at the same office several months after VJ Day.

Although it is not a book of humor, the author’s writing style—accounts of his antics and those of his fellow OSS trainees as they progress from officer volunteers through the intense training program to become fully qualified agents—provides plenty of cause for laughter.

When it was first published in 1957, You’re Stepping on My Cloak and Dagger was an instant hit, especially with members of the American intelligence community. The author of the introduction to the 2004 edition claims that many people told him that it was “the only book they had stolen from a library.” After discovering the book for himself, he went to author Hall and convinced him to offer it for republication. It is an interesting and entertaining book and highly recommended.

American Raiders: The Race to Capture the Luftwaffe’s Secrets by Wolfgang W.E. Samuel, University of Mississippi Press, Jackson, 2004, 484 pp., $35.00, hardcover.

American Raiders: The Race to Capture the Luftwaffe’s Secrets by Wolfgang W.E. Samuel, University of Mississippi Press, Jackson, 2004, 484 pp., $35.00, hardcover.

As it became obvious that the Allies were going to be victorious in Europe, the leadership of the U.S. Army Air Forces made plans to take control of the Luftwaffe’s jets before they fell into the hands of the Soviets. Although both American and British aircraft manufacturers designed and flew their own jets during the war, none of them saw combat.

The Germans, on the other hand, produced successful designs, although they were hampered due to the lack of the proper metals necessary to manufacture jet engine parts capable of withstanding the tremendous heat produced by jet propulsion. Allied airmen realized that the German jets—the Messerschmitt 262 fighter and Arado 234 jet bomber—were vastly superior to Allied designs. Consequently, the United States wanted to obtain as many of the German jets as possible for study by American aeronautical engineers and test pilots who would be designing and testing the aircraft of the future.

Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz, commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, ordered Operation Lusty, a program whose mission was to retrieve German aircraft and missile technology. To run the program, Spaatz recruited Colonel Harold E. Watson, an experienced Air Corps officer with a background in aeronautical engineering who spent much of the war at Wright Field in Ohio. Watson assembled a team of pilots, all of whom had experience in Ninth Air Force P-47 squadrons, and officers to supervise the recovery programs at two installations, Lechfield for the jets and Merseburg for propeller-driven aircraft.

Author Samuel, a retired U.S. Air Force colonel and the author of three previous books, tells the story of the recovery of the German jets from start to finish, including accounts by Army and Navy test pilots who flew the captured aircraft after they were transported to the United States and reassembled. He describes the superiority of the German jet fighters and the fear they evoked among Allied airmen when they made their appearance in the skies over Germany in the fall of 1944.

One particularly interesting revelation describes how senior American fighter pilots sought to deprive the Luftwaffe of their experienced jet pilots by killing them in their parachutes whenever Allied fighters were lucky enough to bring down one of the high speed aircraft. The efforts of Watson and his team paid off as they paved the way for the development of high performance jet engines and aircraft to equip the post-war U.S. Air Force, Navy. and Marine Corps.

This is a very interesting book, especially for the reader with a special interest in military aviation.

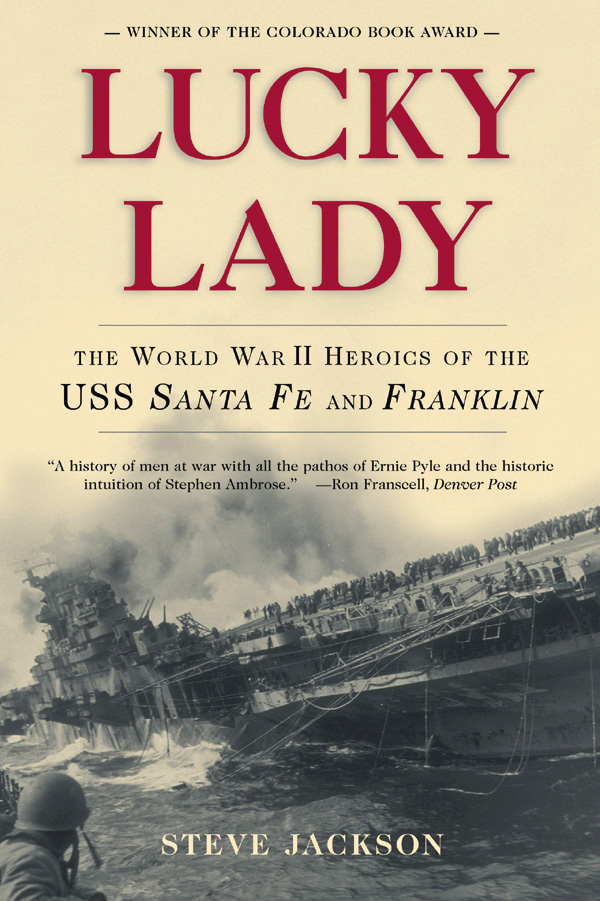

Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics of the USS Santa Fe and Franklin by Steve Jackson, Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, 2003, 504 pp., $16.00, hardcover.

Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics of the USS Santa Fe and Franklin by Steve Jackson, Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, 2003, 504 pp., $16.00, hardcover.

On March 19, 1945, as the Allies were preparing to invade Okinawa, U.S. Naval Task Group 58.2 was steaming 60 miles south of the Japanese island of Kyushu.

Four aircraft carriers, Franklin, Hancock, San Jacinto, and Bataan, made up the strike force of the group, which also included the battleships Washington and North Carolina, the cruisers Baltimore and Pittsburgh, and some two dozen destroyers and destroyer escorts. A sort of odd man in the flotilla was the Santa Fe, a light cruiser of the Cleveland Class, a small, fast ship loaded with antiaircraft guns.

Shortly after 0700 a Japanese Judy dive-bomber dropped out of the clouds and planted two 500-pound bombs on the decks of the Franklin as it was preparing to launch planes. The bombs penetrated the flight deck and exploded on the hangar deck below, setting dozens of airplanes on fire and spreading flaming gasoline throughout the ship. Hundreds of sailors were killed and scores wounded, and the ship was in mortal danger.

In spite of the damage, the stricken carrier did not sink. Surviving members of the crew fought the fire while several destroyers went in close to the ship to pick up men who were flung into the water by explosions or leaped into the water to avoid the flames. Santa Fe’s captain was ordered to evacuate wounded from the stricken carrier and to be prepared to remove the entire crew if it appeared that the ship was in danger of sinking.

Every member of the crew of the light cruiser—indeed, everyone in the task force—was aware of what had happened several months previously when the light cruiser Birmingham had pulled alongside the stricken carrier Princeton in Leyte Gulf. The Princeton’s ammunition magazine blew up, killing more than 200 members of the cruiser’s crew and injuring 400. The crew of Santa Fe had given their ship the nickname “Lucky Lady” in recognition of the ship’s record of having yet to lose a single member of the crew. Fortunately, the Franklin did not blow up and the Santa Fe took on about 800 men from the stricken carrier. Other ships picked up more than 1,300. Even though it had begun to list, the carrier remained afloat and made its way to safety.

There is, however, a dark side to the story. After the ship had been saved, a total of 704 officers and men remained on board the Franklin. The rest of the surviving members of the crew had, without orders, abandoned ship. To their credit, some had been blown into the water by the force of the explosion, but large numbers had jumped from the burning ship in order to save their own lives. Some died when the force of the water on their helmets broke their necks as they hit. The captain considered these men to be deserters and refused to allow them back on board the ship for the journey to Pearl Harbor. Court martial papers were even drawn up against some officers.

Steve Jackson’s father was a member of the crew of the Santa Fe. Jackson began a book on the two ships in 2000, then was motivated to finish it by the events of September 11, 2001. Much of his material is drawn from reminiscences of veterans from the two ships, some gleaned from interviews taken during a recent reunion of Santa Fe veterans, and some from written accounts put down in journals and diaries of the day.

For the most part, Lucky Lady is a collection of personal accounts. Jackson’s work, which won the 2003 Colorado Book Award, is often compared to James Bradley’s Flags of Our Fathers, a comparison that is not without considerable merit.

U.S. Marine Corps Pacific Theater of Operations 1941-1943 by Gordon Rottman, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, 96 pp., $21.95, softcover.

U.S. Marine Corps Pacific Theater of Operations 1941-1943 by Gordon Rottman, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, 96 pp., $21.95, softcover.

Osprey is well known for its various series of military books and this one is part of the Battle Orders series. Consequently, this work follows the Osprey model, meaning that it is heavy on charts, with a lot of maps—many in color—and photographs, with fairly brief narrative.

Chapters are devoted to subjects such as unit organization, tactics, weapons and training, command and control, communications, and intelligence, with other chapters devoted to recruiting, training, and organization, and one single chapter on combat operations. This is a good book for the reader who wishes to learn a little about the role of the Marines from Pearl Harbor to the Solomons.

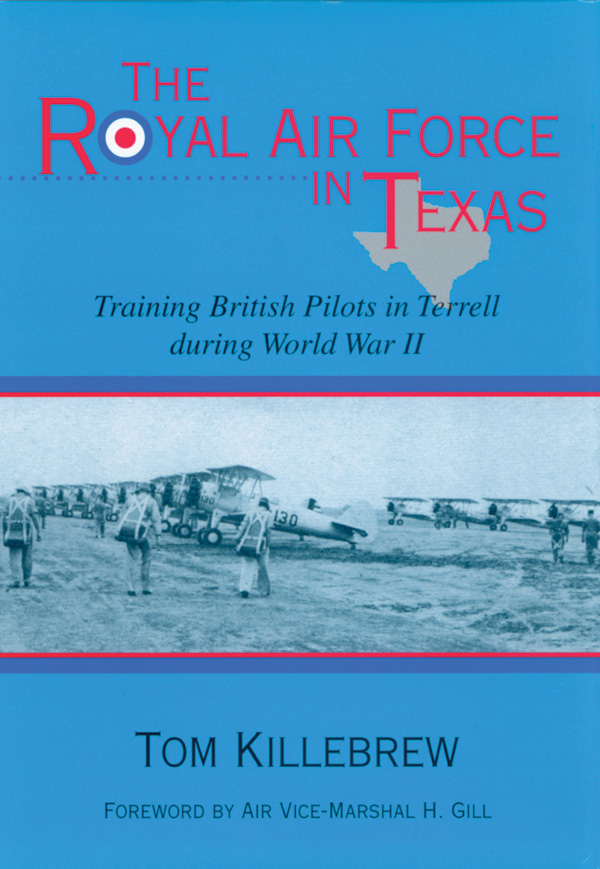

The Royal Air Force in Texas by Tom Killebrew, University of North Texas Press, Denton, 2003, 180 pp., $26.95, hardcover.

The Royal Air Force in Texas by Tom Killebrew, University of North Texas Press, Denton, 2003, 180 pp., $26.95, hardcover.

As the Allies geared up to fight World War II, aircrew training became a huge priority. The important role of air power had been made manifest by Italian successes in Ethiopia and by the German Luftwaffe in support of the fascists in the Spanish Civil War.

Training, however, required airfields far removed from the combat zone, and after the German victory in France in the spring of 1940, there was little space for primary flight training on English soil. The British chose to look elsewhere for flying schools to train their fledgling pilots, navigators, and aircrew. Due to their remoteness from the war zones, most young Britons were sent to training facilities in Canada and South Africa. Although their presence has been largely forgotten, some Royal Air Force cadets trained at flying schools in the United States.

Discussions between Britain and the United States regarding the possibility of establishing British training facilities in the U.S. were actually begun in the spring of 1940, before the Germans overran France, but American neutrality and political considerations ruled out the possibility for the time being. A year later, however, Congress approved the Lend-Lease Act, making it possible for the United States to offer training facilities to Allied nations.

In early March 1941, Army Air Corps General Hap Arnold called the British air attaché to his office. When he got there, Arnold informed the Brit that the United States was going to offer Britain almost 600 American-built trainer aircraft for training at six civilian flying schools. Two were in Oklahoma, while one each were in California, Arizona, Florida, and Terrell, Tex., a small town 35 miles east of Dallas.

The training at Terrell’s Kaufman Country Airport was conducted by a company run by William Long, a World War I pilot who had built up several aviation businesses around Texas after the war. Long was approached by the city of Terrell about the possibility of setting up a training school at their new airport. In May 1941, Long, his operations manager, and a RAF representative went to Terrell to inspect the airport. The result of the inspection was the incorporation of an RAF facility at Terrell as the Terrell Aviation School.

The first RAF students for 1 Basic Flying Training School arrived in Texas in the spring of 1941 and began training at Love Field in Dallas in June. When the facilities at Terrell were ready, the school moved east.

Tom Killebrew’s account of the RAF training at Terrell is well researched and documented, well written and easy to read. While it might not be an important book in the history of World War II, The Royal Air Force in Texas is an interesting book for the aviation history enthusiast and for the reader with an interest in the role played on the Home Front.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments