By Charles Hilbert

In March 1519, a small square of 400 Spanish adventurers under the command of Hernándo Cortés stood at bay on the plain of Cintla in Tabasco, Mexico. The conquistadors were surrounded by thousands of Indian warriors whose hunger for human sacrifices was equaled only by that of their gods. With no avenue of retreat, the Spaniards faced death in battle or an even more horrible death on the sacrificial altars of the Indians’ strange, blood-nourished gods. As their enemies advanced, shooting clouds of sharp arrows and slinging deadly stones, the invaders replied with muskets, cannons, and heavy bolts from their European crossbows. Fighting for his life among the beleaguered Spaniards was a castaway priest-turned-conquistador named Jeronimo Aguilar.

Jeronimo Aguilar: Catholic Warrior Priest of the Xamanzana

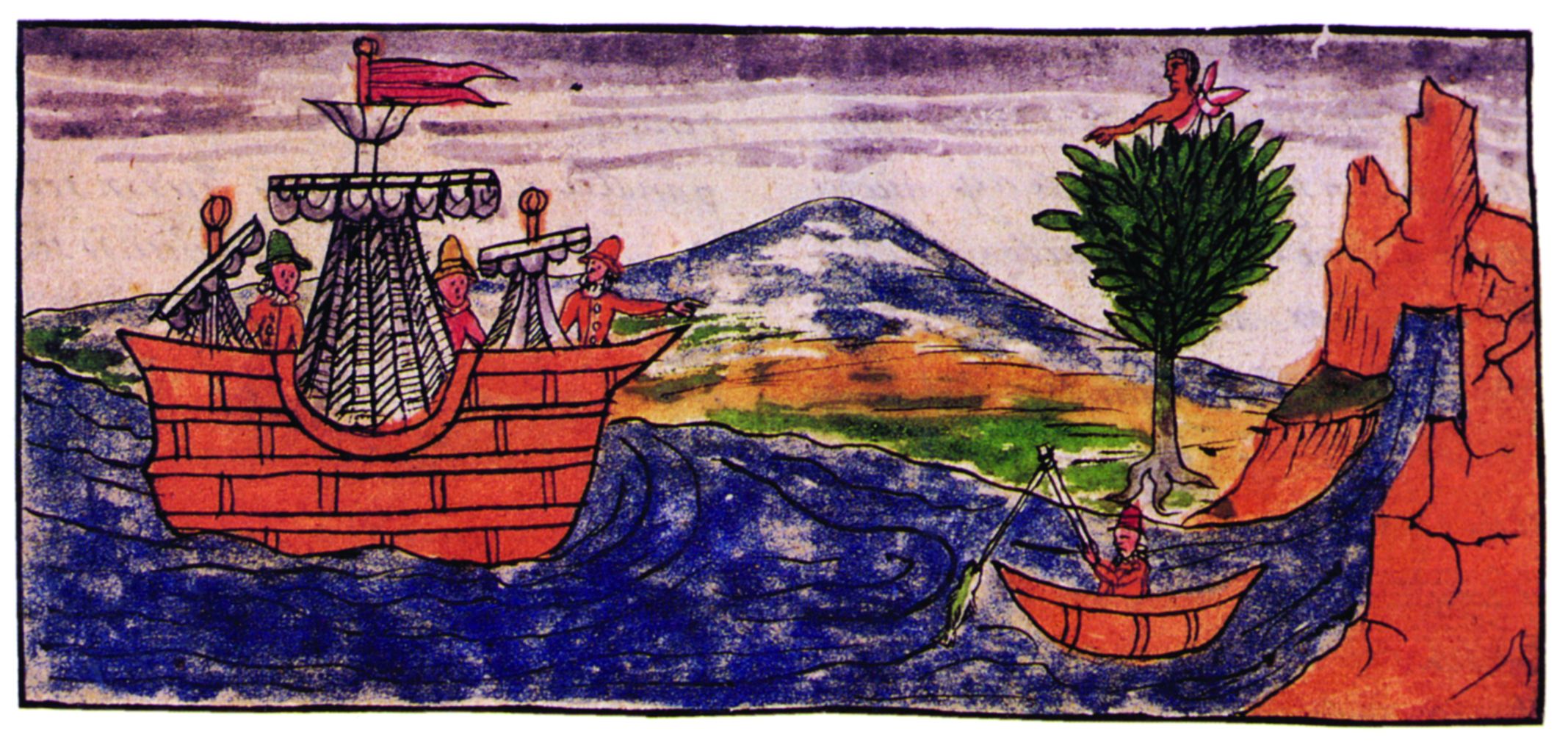

Eight years before Cortés set foot in Yucatan, Aguilar had been a passenger sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo on a ship, captained by Enciso y Valdivia, that struck a reef near Jamaica. Aguilar boarded the ship’s lifeboat along with 15 other men and two women, hoping that the currents would take them to Cuba or Jamaica. The boat had no sails, water, or food, and half the men died of starvation as they drifted helplessly toward the Yucatan peninsula.

After two weeks at sea, the survivors reached land. Upon arrival they were quickly rounded up by the locals, who immediately sacrificed Valdivia and five of his men. The Indians then butchered the bodies and cooked and ate their victims. Aguilar and six others were imprisoned in a wooden cage so that they could be fattened up for the next round of sacrifices. Somehow they managed to escape. Stumbling through the thick, tropical jungle, Aguilar was recaptured by the tribesmen of Xamanzana, who brought him to their chief, Aquinouz. Aguilar spent the next three years at hard labor. When he wasn’t working in the fields, he was hauling wood, water, and fish on his back.

Aguilar was a good worker and an obedient servant. Possibly to reward him for his diligence, Aquinouz’s successor, Taxmar, offered the Spaniard a wife. But Aguilar had taken holy orders back in Spain and was not about to cohabitate with an infidel. Amused, Taxmar arranged many temptations for his unusual slave, even sending him to fish with an attractive young girl as his overnight companion. Aguilar put his faith in God and his tattered Book of Hours, his only possession to survive the shipwreck, and he remained celibate. This impressed Taxmar even more, and he placed Aguilar in charge of his household, including his wives.

No less bellicose than the average conquistador, Aguilar asked to be allowed to fight his master’s many enemies. Aguilar’s prowess as a warrior must have been formidable. Taxmar’s chief enemy, unable to defeat him in battle, sent a message complaining that Aguilar’s presence on the battlefield was an impious insult to their gods; he suggested that to make amends Aguilar should be sacrificed. Taxmar refused, but his council advised him to comply with their enemy’s demand. Taxmar was reluctant to order the death of such a valuable and honorable servant, and he asked Aguilar what he would do in his place. Aguilar, of course, was not about to countenance his own death, and he promised Taxmar victory if he would follow his battle plan.

The two warring camps advanced on each another with a shower of arrows and stones. As Aguilar had advised, Taxmar fell back. Eager to exploit their victory, Taxmar’s rivals rushed forward in pursuit, but their overconfidence was fatal. Concealed in the tall grass, Aguilar and a small unit of his Indian compatriots let their enemies pass, then fell on their rear. Taxmar and the main body of troops renewed the attack. Caught between hammer and anvil, as it were, Taxmar’s surprised enemies were crushed in a bloody vise.

An Expedition for the Governor of Cuba

In 1518 the governor of Cuba, Diego Velasquez, sent Juan de Grijalva with four ships and 240 men back to Yucatan to trade for gold and silver, and if possible, to found a settlement. They touched land briefly at Cozumel, but all the inhabitants fled at their approach. They then sailed to Champoton, where the Indian inhabitants began to shoot arrows at them. So thick was the storm of missiles that every other man in the Spanish force was wounded, even though they had adopted the Indians’ own type of padded armor, it being impossible to wear metal armor in the equatorial heat. The Europeans fought their way ashore and easily hacked through the Indians’ wicker shields and cotton armor. The Indians fought back fiercely enough to kill seven Spaniards, but they were finally driven into the swamps that bordered the town.

After three days the expedition set sail up the coast. Tacking close to shore, they reached a wide river that the Indians called Tabasco and decided to rename it Rio de Grijalva. Indians from the nearby town of Tabasco lined the river banks in canoes, armed for war. Denied passage upriver, the Spaniards landed on a palm-covered headland a mile or so from town. No sooner had they touched solid ground than a fleet of 50 well-armed canoes glided into view. After a few tense moments hostilities were avoided, and the local chiefs were placated by the gift of green beads that the Indians thought were jade. The locals seem to have figured out the Spaniards’ purpose. Pointing to the sunset, they kept repeating, “Mexico, Mexico.” None of the Spaniards knew what Mexico meant, but they knew what gold was, and they immediately set sail.

“Dios y Santa Maria de Sevilla”

They had better luck with the next tribes they encountered, managing to bring back a substantial quantity of gold to Cuba. Impressed by the precious metals, Velasquez appointed Hernando Cortés to command another, even larger expedition. The governor of Cuba had heard rumors of Spanish captives, and in addition to gold, he ordered Cortés to bring back any Castilian castaways. In February 1519 Cortés set sail for Cozumel with 11 ships, 550 soldiers, 16 horses, and 12 field pieces. Along the way, he was held up by a lost rudder and his henchman, Pedro de Alvarado, landed at the island two days before his commander. At his approach, the Indians left their villages and fled to the interior. Alvarado followed them and quickly appropriated their food and any items of gold that he could find. He captured two men and a woman. As he was making his way back to the coast, Cortés landed. Upon learning of Alvarado’s actions, he upbraided his captain, gave the captured Indians some glass beads, and sent them off to tell their chief that he had nothing to fear from the Spaniards.

The Indians returned the next day. Cortés asked the local leaders if they knew of any Spaniards living in the vicinity. They replied that there were bearded men living as slaves in Yucatan, two days’ journey to the west. Cortés immediately decided to attempt a rescue. His pilots advised against a landing on the rocky coast, and the Indians told him that the prisoners would probably be killed as soon as he attacked. They suggested that he ransom the captives. Cortés induced three Indians to take a letter to the tribe in question. The messengers set off inland, and two days later handed Aguilar the letter and the beads. When he read the letter and received the ransom, he carried the beads delightedly to his master and begged leave to depart. Taxmar gave him permission to go wherever he wished. Aguilar left with the two Indians who had brought him the letter and followed them to Cape Cartouche. But his would-be rescuers had gotten tired of waiting and sailed back to Cozumel. Aguilar returned unhappily to Taxmar.

Cortés was less than satisfied with the way things had turned out and, after spending some time forcibly converting the locals to Christianity, he resumed his voyage of conquest. Not far from Cozumel, Juan de Escalante’s ship sprang a leak and headed back to the island. It took the Spaniards four days to recaulk Escalante’s ship. During that time Aguilar, learning of their unexpected return, hired a canoe and sailed for Cozumel.

While hunting for wild pigs, some of Cortés’s men spotted Indians in a canoe approaching from Cape Cartouche. Cortés sent Andres de Tapia and two men to intercept them. They concealed themselves among the lush, tropical foliage and watched while the Indians walked up the beach. Suddenly they appeared with drawn swords. Aguilar’s companions were struck with fear, but the Castilian castaway ran forward, crying, “Dios y Santa Maria de Sevilla.” After eight years among the Maya, his words were ill pronounced, but the conquistadors understood them. Tapia embraced him and led him to Cortés.

Aguilar was burned brown by the sun, and his hair and dress were those of an Indian. As the group reached him, Cortés asked, “Where is the Spaniard?” Aguilar replied, “I am.” Cortés took off his cloak and wrapped it around Aguilar’s shoulders. A few days later the conquistadors sailed from Cozumel, but the ships’ pilots advised against landing in the shallow harbor, so the conquistadors continued their voyage, heading toward Tabasco, where Grijalva had successfully traded beads for gold and silver.

Fighting Their Way into Tabasco

Unable to navigate the Rio de Grijalva with their ships, Cortés and his men took the ships’ boats and landed on the headland a mile northeast of Tabasco. Soon the river and the surrounding area were covered with hundreds of hostile Indians girded for war. As a large canoe coasted past his position, Cortés put Aguilar to work. He learned that the locals, having been accused of cowardice by the Indians of Champoton because they had traded with Grijalva, were now determined to resist all invaders. They threatened to kill Cortés and his men if they did not leave. After further fruitless attempts to reach a peaceful understanding, the Indians left with a final threat to kill the Spaniards if they progressed beyond the palm trees on the beach.

Cortés planned accordingly, outfitting each boat with three cannons, crossbowmen, and arquebusiers. Some of Grijalva’s former companions remembered that there was a narrow path that led from the palmed headland to the town of Tabasco. Cortés sent some men to reconnoiter and, upon their return, ordered an attack for the following day. The next morning, after Mass, Alonso de Avila and a hundred men set off through the palms for Tabasco. Cortés and the rest boarded the armed boats and sailed upriver toward the town. When the Indians saw the small Castilian flotilla heading for their village, they manned their canoes and lined the riverbanks with warriors. Cortés tried one more time to effect a peaceful settlement, but the Indians continued their threats, then began to shoot clouds of arrows at the Spaniards in their boats. Surrounded by canoes full of warriors firing at them, Cortés and his men made for shore.

The banks of the river were bordered by mangrove swamps, and the Spaniards, jumping into the waist-deep water, struggled through the mud as arrows flew thick around them and the Indians on the bank thrust at them with long obsidian-bladed lances. The Spanish at last fought their way ashore and forced the Indians to retire to the wooden barricade they had erected around their town. Under fire, the conquistadors ripped their way through this obstacle and forced the Indians back down the streets of their city, fighting every step of the way. At this point, Avila showed up behind the Indians, and the combined forces of the Spaniards put the Tabascans to flight. Cortés camped in the city square among the temples of the Indian gods.

Crushing the Native Counterattack

In the morning, Cortés sent out 200 men to reconnoiter, but they were driven back to Tabasco by multitudes of Indians. Cortés and Aguilar interrogated two prisoners taken in the fighting and learned that the neighboring tribes were gathering for an all-out attack on the invaders. Cortés immediately ordered the horses to be brought ashore and the men to prepare themselves for battle.

The next morning, the conquistadors heard Mass, and with Cortés commanding the cavalry, the Castilians set out for the treeless plain where his men had been attacked the day before. Nearby was the town of Cintla. Cortés and the horsemen were forced to detour around some swampy ground, and the Spanish infantry lost sight of them. As they reached the plain of Cintla, the conquistadors encountered thousands of Indians on their way to retake Tabasco. All the men wore great feather crests, carried drums and trumpets, and were armed with large bows and arrows, spears and shields, swords, stones, and fire-toughened darts. The Indians rushed the conquistadors, bombarding them with a rain of arrows, darts, and stones and wounding 70 in the first attack. As the missiles fell thick among the Spaniards, they returned fire with their matchlocks, crossbows, and field pieces. The Indians were tightly packed, and the fire of the cannons mowed them down by the dozens.

After the initial long-range fighting, the Indians closed and sought to wound the invaders with their obsidian blades, but the Spanish soldiers fought back with their merciless Toledo steel. They cut and stabbed the Indians through their cotton armor and formed a defensive square. Cortés and his small band of horsemen, having circumnavigated the swamps and irrigation ditches that crisscrossed the area, attacked the Indians’ rear. Since the plain was covered with Indians, it took a while for the Spanish infantry to realize that Cortés had arrived at last. When they saw the horsemen in the distance, they redoubled their efforts, hacking and stabbing until the Indians, caught between the swords of the foot soldiers and the lances of the horsemen, broke formation and fled in all directions.

Donna Marina and the Way to Mexico

Although they had fought bravely, the Indians were shocked at the sight of the horses and riders, something they had never seen before, and as they ran about in confusion, the Spanish horsemen speared them without mercy. Most of the Spaniards were wounded, but only two had been killed. Two high-ranking Tabascans had been taken captive, and Aguilar advised Cortés to give them beads and send them off to negotiate a peace with their fellows. They left, and the next day 15 slaves came to Cortés, bringing gifts of food. Cortés received them respectfully, but Aguilar, who was familiar with the Indians’ customs, berated them and sent them away, ordering them to send a more dignified delegation. In the following days, 30 important caciques came to Cortés, bearing gifts of gold and 20 women. Cortés also asked the Indians where they had gotten the gold. They pointed to the west and said, “Mexico.” Cortés wasted no time hoisting sail.

A few days later, approaching their next landfall, the Spaniards spotted some large canoes coming toward them. The Indians headed for Cortés’s flagship. Coming aboard, they asked to speak with the expedition’s leader. They were representatives of Moctezuma, and no one, not even Aguilar, could understand their speech. Then one of the Indian women pointed out Cortés. She was a Mexican princess named Malinali, and had been sold by her Aztec mother and stepfather to the Maya of Yucatan. Cortés spoke Spanish to Aguilar, who translated his words into Mayan for Malinali, who then spoke to the visitors in Nahuatl.

The Spanish changed Malinali’s name to Marina and, because of her noble birth, called her Dona Marina. For the next two years, she and Aguilar helped Cortés negotiate, interrogate, and gather intelligence, while the conquistadors slowly, methodically, and bloodily conquered the Aztecs. Aguilar was last heard from in 1529, when he testified against his former commander at an inquiry regarding the death of Cortés’s wife, Catalina. By then, many of the conquistadors had turned against the conqueror of Mexico, who had managed to cheat them, the king of Spain, and his Indian allies out of most of the spoils of war. Shortly after his court appearance Aguilar died of paralysis, an oddly peaceful death for so adventurous a life.

It would have been nothing but a minor incident- – but for the discovery of Malinali (“Doña Marina”). She was the key that unlocked Mexico to Cortés, – becoming both his concubine and mother of his firstborn son (Martín Cortés).

Cortés later had a second, legitimate son by his 2nd wife, ALSO named Martín.

Surprisingly ‘Martín El Mestizo’ and ‘Don Martín’ got along very well together. But later in life, both brothers were accused of conspiracy to overthrow the King’s government in New Spain. They were exiled from Mexico City back to Spain, where Martín El Mestizo became a distinguished officer in the king’s army.