By Eric Niderost

When Albert Einstein arrived in Pasadena, California, in early 1933, he was to take up his duties as visiting professor at the California Institute of Technology for about three months. CalTech President Robert Millikan had made all the arrangements for the world famous theoretical physicist, but Einstein discovered there was a small price tag: he would have to make a speech promoting German-American relations. Millikan had procured a $7,000 grant—a substantial sum for the early Depression days—from the Oberlaender Trust, a U.S.-based foundation that promoted cultural exchanges between America and Germany.

The grant would be more than enough to fund Einstein’s California stay, and the professor had no objections to making such a public appearance. Of course, there were speeches—and then, there were speeches. Once Einstein arrived in Pasadena, Millikan politely arm-twisted the physicist to cancel another talk that was to have been made with the University of Southern California’s chapter of the War Resisters League. The USC speech was to have denounced forced conscription, what Americans would call the draft—to build armies in Europe and elsewhere.

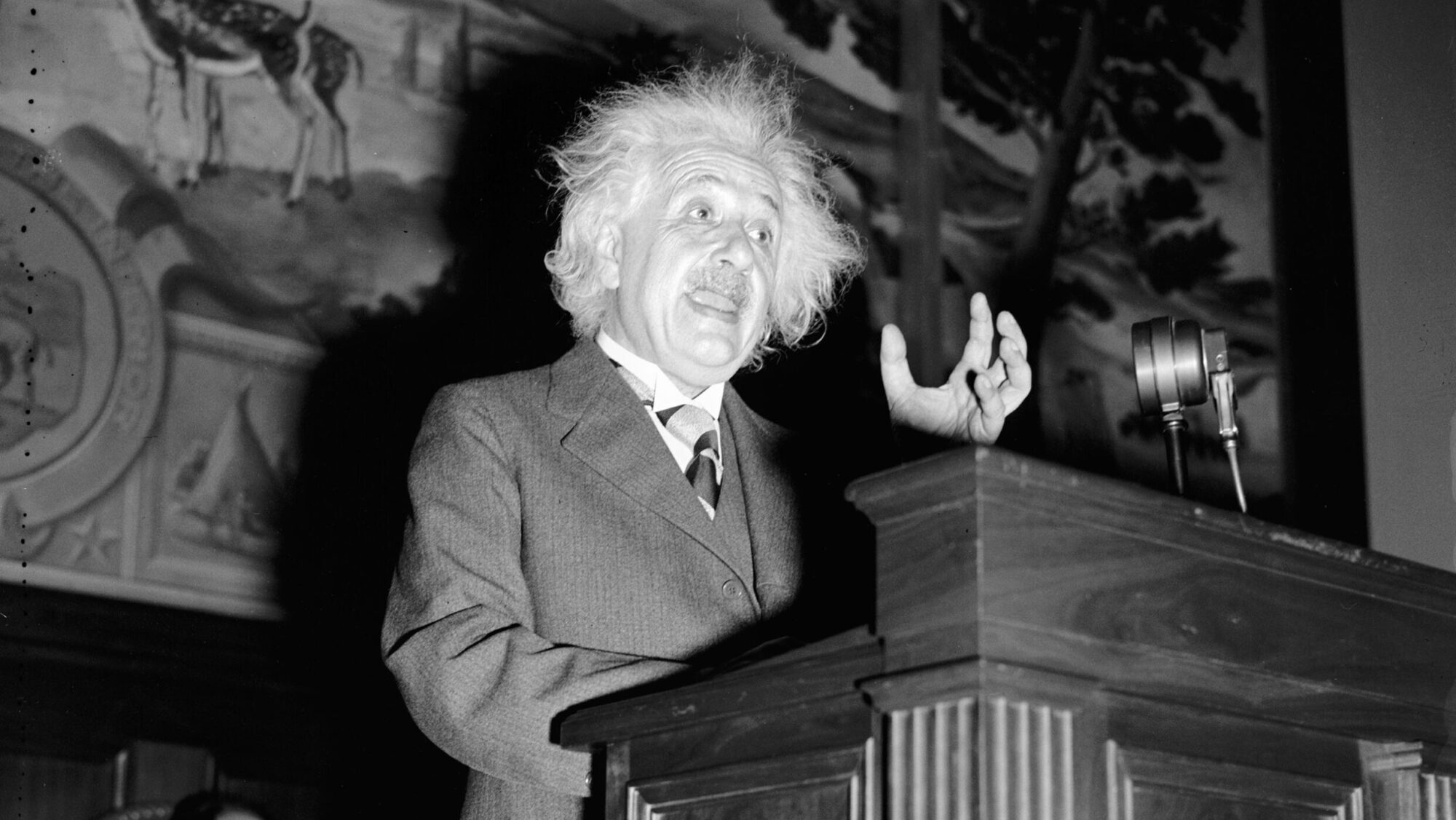

Einstein’s German-American relations appearance was a gala event attended by thousands of people at the Pasadena Auditorium. To ensure an even wider audience, the speech would be broadcast by NBC radio, this at a time when virtually every American, regardless of class or economic status, seemed to have a receiver.

Einstein spoke of the Depression, which he blamed in part for the technological advances lessening the need for “human labor” and thus a decline in the public’s purchasing power. He also noted how words can be laden with emotion, and if misused, become vehicles of hate. He offered the word “Jew,” as used by “the reactionary group in Germany,” as an example.

As a pacifist, Einstein said Germany should not be allowed to introduce mandatory military service. “Universal military service means the training of youth in a warlike spirit,” he said. The professor was a popular figure in America, but the impact of his speech was probably minimal. Franklin D. Roosevelt was about to take office as President, and economic concerns were uppermost in most people’s minds.

In retrospect, that 1933 Pasadena speech was the first round in a contest that would pit the scientist against Hitler and Nazi Germany. On January 30, 1933, one week after Einstein delivered his remarks in Pasadena, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. Once the Nazis took control, Einstein’s opposition to them took on an added dimension. The physicist was not only the most famous living scientist, he was also Jewish, which made him a special target for Nazi ire and put his life in danger.

Albert Einstein was born in Ulm, Germany, in 1879. As a teenager, his growing aptitude and lively interest in science led him to get a degree in mathematics and physics at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich. He became a Swiss citizen and obtained his doctorate but found he could not obtain a teaching position. As a fallback measure Einstein took a job at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern.

His patent office duties were not onerous, leaving him plenty of time to work at his real profession, theoretical physics. Beginning in 1905, he wrote and published a series of groundbreaking scientific papers that revolutionized our thinking about the universe. In 1915, he produced the general theory of relativity, which he considered the masterwork of a lifetime. Briefly, it said that gravity, as well as motion, affects time and space.

Einstein’s theory of relativity was truly a scientific revolution that overturned the system Issac Newton had established in the 17th century. Newton’s ideas, which had been treated as “gospel” over 250 years, had been replaced by a new cosmology in which the universe was not unchanging and static, but was actually capable of expanding and contracting.

The physicist continued to work in the patent office until 1909, when he finally landed a position teaching at the University of Zurich. By 1913 he was back home in Germany as a director of the University of Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics. Einstein would remain in Berlin for the next 20 years.

After World War I, Einstein won the Nobel Prize for his work on a complicated subject called the “photoelectric effect,” because his theories on relativity were still controversial. But while the scientific community still harbored doubts, the public did not. The impact of modern media and advertising had really come to the fore by the 1920s. Radio broadcasts reached millions, newspaper circulation was at its height, and newsreels in movie theaters brought the world to your neighborhood.

Albert Einstein was the first celebrity scientist, a man whose fame equaled, and at times eclipsed, the movie stars of the time. When the liner Rotterdam docked at Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1931, it was greeted by 5,000 New Yorkers eager to catch a glimpse of the steamship’s most famous passenger, Dr. Einstein. On another occasion a decade later, while landing in San Diego, cheering students at the pier chanted his name, “Einstein! Einstein! Einstein!” with all the enthusiasm of a championship college football game.

His fame was baffling, even to the great scientist. A man who could unlock the secrets of the cosmos stood clueless and mystified before the intricacies of the human heart and mind. And even more baffling was the fact that his fame was based upon concepts completely esoteric to the average person. Even some scientists didn’t fully grasp what he was driving at, let alone the general public.

In 1931, Einstein went to the premiere of City Lights with Charles Chaplin. Applauded on their way into the theater, Chaplin remarked, “They cheer me because they understand me, and they cheer you because no one understands you.” Einstein wrote later, “I never understood why the theory of relativity with its concepts and problems so far removed from practical life should have met with a lively…resonance among broad circles of the public.”

Einstein’s own appearance and personality answers at least some of the questions involving his popularity. His deep-set eyes, often twinkling with merriment at a joke or quip—he had a self-deprecating sense of humor—were offset with a walrus mustache and strands of long hair that burst from his head like the waves of energy he liked to mathematically describe.

Newspaper reporters and photographers loved him, simply because he made good copy, and his eccentricities were endearing, not repulsive. He did not like to wear socks and preferred comfortable old sweaters. The good doctor was avuncular, easy to approach, and not above answering his own door if someone came by. Once, after he made America his permanent home, some girls came by his house to sing Christmas carols. To their utter delight, Einstein grabbed his violin and added some music to their songs. Occasionally, a child might come by and ask for help on math homework, and if not busy, Einstein was more than happy to lend a hand.

Einstein was the stereotypical “absent minded professor,” distracted and hardly knowing his surroundings as he mulled over endless equations, jotting the symbols down on paper as fast as they were born in his brilliant, ever-probing mind. Though his head might have been in an abstract cloud, his feet were firmly planted in the sobering realities of the world. Einstein cherished freedom, especially freedom of thought. He hated injustice, and above all, hoped that war, the scourge of humanity, would be abolished forever.

In September 1930, Depression-wracked Germany held a national election, and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party—the Nazi Party—won over six million votes to become the second largest party in the Reichstag. Controlling 107 seats, they were now a force to be reckoned with. At first, Einstein felt the Nazis were an anomaly, a “childish disease of the (German Weimar) Republic” brought on by the worldwide Depression, “a momentarily desperate economic situation.”

When asked about Adolf Hitler in December 1930, Einstein replied, “I do not enjoy Herr Hitler’s acquaintance. He is living on the empty stomach of Germany. As soon as economic conditions improve, he will no longer be important.” He was guardedly optimistic, but still he felt the “solidarity of the Jews, I believe, is always called for.” Jewish people, the target of hate and violence for centuries, had to closely monitor the situation lest they be swept away.

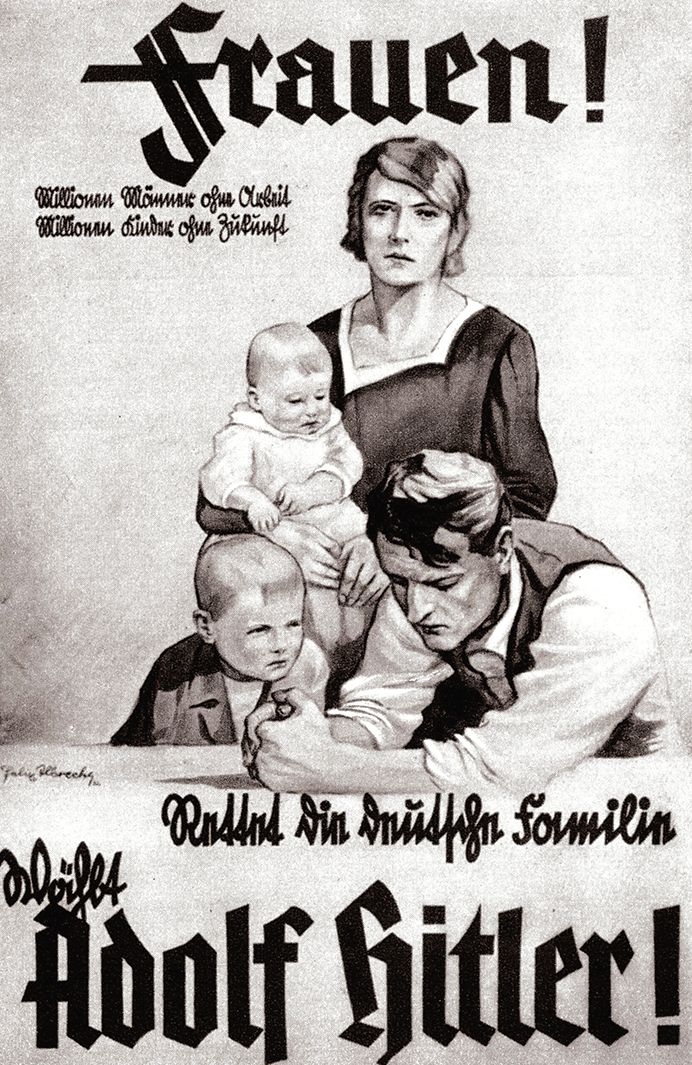

The rise of Hitler paralleled a rise of militarism and potential rearmament. Hitler did little to hide his loathing of the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. Versailles had limited the German army to 100,000 men, the Germans could not create an air force, and their warships had to meet strict guidelines on tonnages and armament. It was plain that Hitler intended to ignore the treaty and rearm Germany if he ever gained power.

Einstein, in contrast, was a passionate pacifist, who once declared he would rather be “torn limb from limb” than take part in a war. He tried to use his celebrity to promote peace—writing, campaigning, serving on committees, raising money, and making speeches against war. But by December 1932, he came to realize that it was all in vain, though he never gave up hope.

That month, Einstein left Berlin for Pasadena, California, to deliver that speech promoting German-American friendship. His wife Elsa was to go with him, so their house at Caputh, a village near the Havel River in Potsdam, was to be closed.

Despite appearances, Einstein knew too well what was happening in Germany. As they left for America, said to Elsa, “Take a good look—you will never see it again.”

On January 30, 1933, Hitler took the oath as chancellor of Germany. Einstein was still in Pasadena, frankly enjoying his life under the California sun. In February of that year, a photo showed a beaming Einstein trying his hand at riding a bicycle. It displayed the great scientist’s whimsical side, but behind the scenes he was monitoring events in Germany.

At first, the situation seemed fluid, and Einstein toyed with the idea of returning to Germany in April. But then the Reichstag was burned, and a plague of brown-shirted Nazi stormtroopers looted Jewish homes throughout the country. “Because of Hitler,” Einstein commented to a friend, “I don’t dare step on German soil.” He decided to travel to Belgium, and some suggested Switzerland as an ultimate place of refuge. While still in transit, Einstein learned his Caputh house had been raided by the Nazis under the pretext of searching for a cache of “communist” weapons. There were none, of course, but later they came back and confiscated his beloved boat.

Einstein decided to take a public stand.

In Europe, he renounced his German citizenship and resigned from the Prussian Academy. His criticisms stung the Nazi government and stirred a firestorm of denunciations from the German press. One headline read,“Good news of Einstein—he’s not coming back!” Another paper declared that the physicist was “…never a German in our eyes and who declares himself a Jew and nothing but a Jew.”

Worse was to follow. His bank accounts were seized and scientific works publicly burned. Then, the Nazi propaganda war against Einstein took a more sinister turn. One of its anti-Semitic journals ran a piece about the “enemies of Germany.”

Titled “The Jews are Watching You,”(Juden Sehen Dich An), it went on to describe the scientist as having “…discovered a much-contested theory of relativity… Showed his gratitude (to Germany) by lying atrocity propaganda against Adolf Hitler.” A photo was included, and the caption under Einstein’s picture read, “BIS JETZT UNGEHAENGT” or “not yet hanged.”

Einstein’s life was in real danger, though he remained calm and unconcerned about the threats. But the danger became a reality when on April 30, 1933, Nazi assassins killed Theodor Lessing, a controversial German-Jewish philosopher living as a refugee in Czechoslovakia. He was shot and died the next day. There had been a price on Lessing’s head, and the killers were honored in Germany. Lessing’s photo had also been published with the caption “Not yet hanged.”

After the assassination, more rumors circulated that Einstein was next on the list for extermination. One story claimed there was a $5,000 bounty on the physicist’s head—more than $100,000 today. Hearing this, Einstein playfully touched his head and said, “I really had no idea my head was worth all that!” But Lessing had been his friend, so he must have privately grieved even if he showed nonchalance about his own fate.

On a more serious note, he added, “I have no doubt it (the purported reward for his death) is really true, but in any case I await the issue with serenity.” Instead of returning to Germany, Einstein went to Belgium. Now rootless and technically homeless, he needed time to determine his next course of action. He considered making Zurich his permanent home—he still had Swiss citizenship—but just wasn’t up to the paperwork it would require to bring his family as well.

Mulling it over, he decided to take up temporary refuge in Belgium. Einstein rented a house on the sand dunes near Ostend, whimsically named Coq sur Mar, or “Rooster by the Sea.” Various universities were sending him offers of employment, including Oxford and Leiden. Though the physicist didn’t know it, his decision was literally one of life and death. If he had chosen Leiden, for example, he could have been a victim of the Holocaust when the Nazis occupied the Netherlands in World War II.

It was now the summer of 1933, and the threats against his life were unending. Einstein was a personal friend of Albert, King of the Belgians, and his consort Queen Elizabeth, and the royal pair took measures to protect their distinguished guest. Two Belgian police officers were assigned to Einstein as personal bodyguards. He didn’t like to feel watched all the time, even if it was for his own safety, but perhaps because of his wife’s anxieties, he accepted the police protection with a good-natured shrug.

Einstein’s next stop was England. He was scheduled to give a lecture at Oxford University, but he had visited the island nation before, loved it, and needed no excuse to go there. It was during this summer of 1933 that he first met Winston Churchill, very much a kindred spirit in terms of opinions on Germany and Hitler. But Churchill was then in a kind of political limbo, which later historians call the “wilderness years.” Churchill was a pariah, ignored and barely tolerated, but Einstein and the “exiled” politician got along well.

England was pleasant, but the threats of assassination still dogged Einstein. Commander Oliver Locker-Lampson, a member of Parliament, feared for his friend’s life and decided to offer Einstein a secluded cottage that was on a moor near the southwest of London close to Comer. The professor could stay there before another anticipated trip to America.

Einstein readily accepted. The vastness and solitude of the windswept moors of Norfolk appealed to the scientist. Though the danger was real, once he was in England he was relatively safe even without Locker-Lampson. In fact, Locker-Lampson couldn’t help displaying a bit of showmanship when he had press photographs taken of the physicist and two beautiful shotgun-wielding women. Amused, Einstein quipped that “the beauty of my bodyguards would disarm a conspirator sooner than their shotguns!”

Other photos show male guards, casual but alert, next to a smiling Einstein just outside his cottage/hut. Einstein loved this “hermit” life, where he could focus on mathematics and physics. No need to lecture, or deal with the petty problems and everyday concerns of normal existence. If he became bored, he played his violin, or a tune on a piano that had been provided by his host in another hut.

In the end, he decided to accept an offer from the newly established Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, New Jersey. The United States would be his home for the rest of his life. But before he left England, Einstein gave a speech in English at London’s Royal Albert Hall. The event was designed to raise money for displaced refugee scientists; not all were as famous, or as lucky, as Einstein. While not mentioning the Nazi government directly, Einstein spoke about the rising threat to freedom, and without freedom “there would be no Shakespeare, no Goethe, no Newton, no Faraday, no Pasteur, no Lister.”

At first, the world was too preoccupied with their own internal problems and the Depression’s economic storms to really care what was going on in Germany. Einstein was one of only a handful of people—Winston Churchill was another—who tried to raise the alarm about Hitler and his intentions, but were ignored or ridiculed for their efforts.

“I cannot understand the passive response of the whole civilized world to this modern barbarism,” he wrote, referring to the Nazi menace. “Does the world not see that Hitler is aiming for war?” Though ambivalent about his worldwide fame, Einstein used his celebrity to sound the alarm about the Nazis.

Einstein denounced Nazi aggression, but didn’t demonize the German people. Even in the early 1930s, he could see the Nazis were poised to start “a war of extermination against my Jewish brethren.”

Einstein’s own views on war and pacifism began to change in the 1930s. Reluctantly, he admitted military resistance to tyranny was the only hope for freedom and justice. “To prevent a greater evil, it is necessary that a lesser evil—the hated military—be accepted for the time being,” he wrote.

More startling was his admission—at least in theory—that he would take up arms to oppose dictators like Hitler. “In the heart of Europe,” he wrote in a missive later published in the New York Times, “lies a power, Germany, that is obviously pushing towards war with all available means. I should not, in the present circumstances, refuse military service. Rather I should enter such service cheerfully in the belief that I would thereby be helping to save European civilization.”

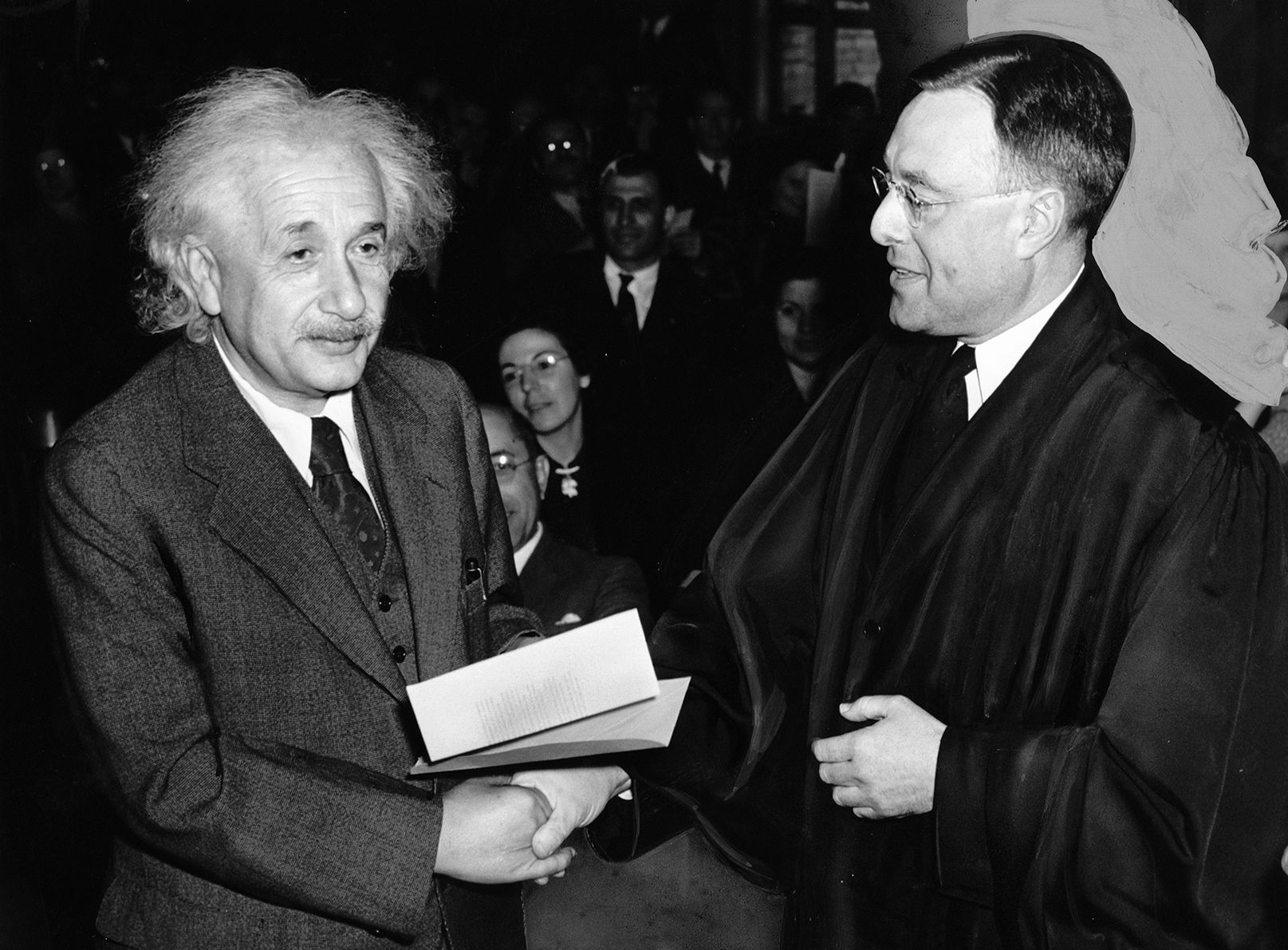

Einstein arrived in New York aboard the liner Westmoreland on October 17, 1933. At 54, he was still the world’s most famous scientist. He grew to love Princeton and the U.S, eventually becoming a citizen in 1940.

Einstein was not the “father of the atomic bomb” as is sometimes still claimed, based on his famous equation, E=mc2, or “Energy equals mass times velocity squared.” His equation itself wasn’t a breakthrough, but it did explain what was going on. Einstein’s theory behind the equation holds that energy and mass are essentially the same thing. In splitting atoms —fission—the energy in their mass is released, producing enormous power.

In 1938, German scientists achieved nuclear fission, demonstrating that a uranium atom can be split, and as it divides, it loses mass, which is then converted to energy. It was this energy that could potentially be used to create an explosive device of immense destructive power. Hungarian scientist Leo Szilard, who was then living in the U.S., worried the Nazis might soon possess the unthinkable—an atomic bomb.

Szilard knew there was no time to waste and that only Einstein had the celebrity and prestige to make Roosevelt take notice. Szilard contacted Einstein, and they drafted a letter to the president. Dated August 2, 1939, it spoke of uranium as a new power source and warned of the German progress in fission. Einstein warned about an atomic bomb, suggesting that if one were smuggled in a ship, it could obliterate a port city.

Though Szlard and Einstein were wrong about the delivery method, their scenario moved an alarmed Roosevelt to action. The president authorized a board to look into the matter, but the Roosevelt Administration only approved $6,000 for graphite and uranium experiments. Frustrated at the slow progress, Szilard again turned to Einstein, who wrote a second letter to the President urging him to take greater action. Once again Roosevelt responded in a positive way, but serious work didn’t really begin until America entered the war in December 1941.

When acting Army Chief of Staff Brigadier General Sherman Miles was organizing the committee to explore the idea of an atomic bomb, he hesitated to add Einstein. It didn’t matter that Einstein’s letter was the catalyst for the committee or that Einstein was able to directly communicate with Roosevelt, who admired the physicist. Miles contacted FBI director J. Edgar Hoover for guidance.

Hoover’s motives are unknown, but he negatively reviewed Einstein—whose antiwar pacifism made him suspect in Hoover’s eyes. In 1932, the scientist had refused to attend the World Antiwar Congress because it glorified Soviet Russia. Yet to Hoover, Einstein was a pro-communist and a rabid supporter of Joseph Stalin’s Soviet system.”

Longtime contributor Eric Niderost is a college professor in the California Bay Area.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments