By Patrick J. Chaisson

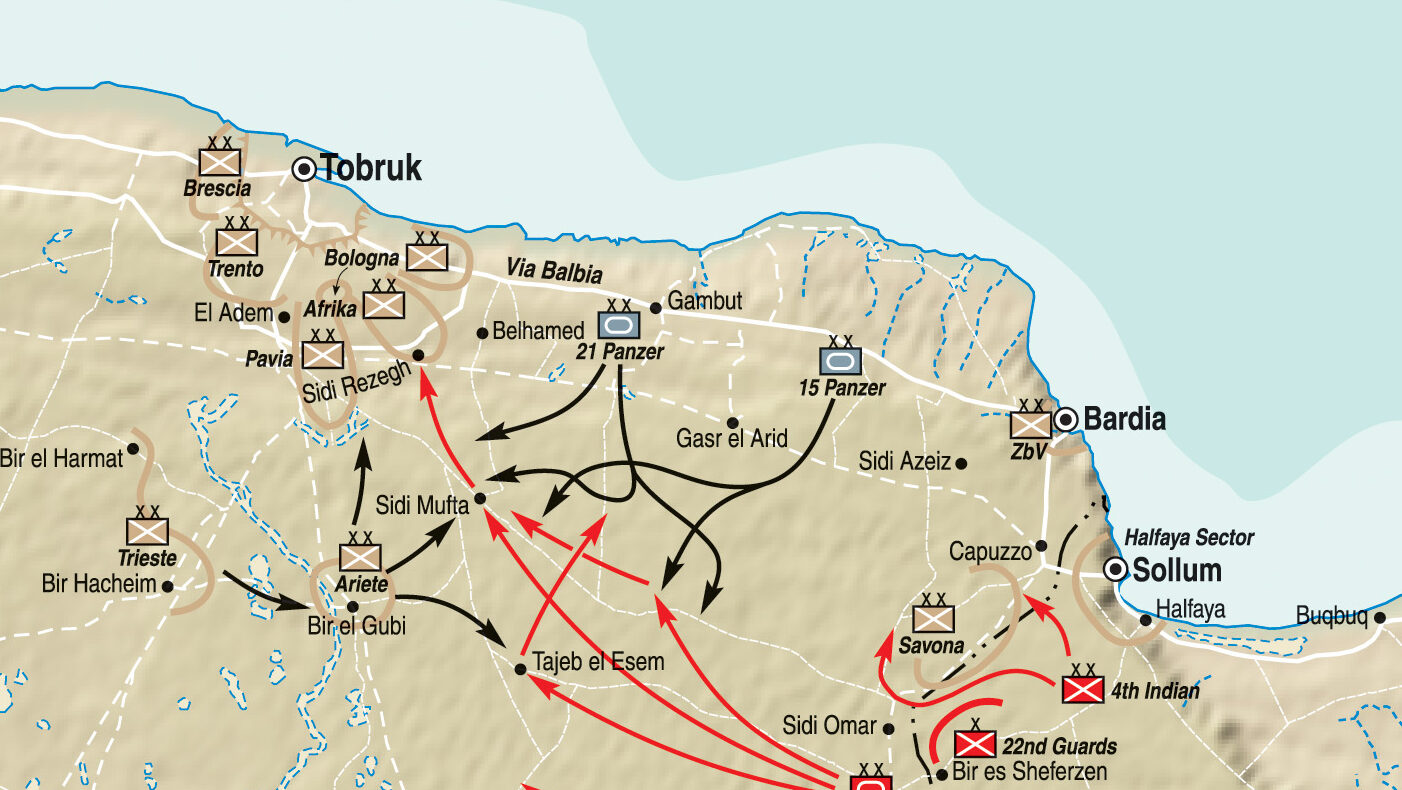

President Franklin D. Roosevelt electrified the world when on December 29, 1940, he called on America to become “the great arsenal of democracy.” In this speech he urged a national effort to produce war matériel while pledging to support Great Britain in its fight against the Axis powers. By providing arms and supplies to the British, Roosevelt nudged the nation farther away from its posture of neutrality and closer toward direct participation in World War II.

Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy” speech sent a strong message to friend and foe alike. Yet it was one thing to promise these munitions and quite another matter to actually manufacture them. In 1940, America was still emerging from the decade-long Great Depression. Furthermore, a national spirit of isolationism fueled by the horrors of World War I kept military budgets small throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

As a result, the United States found itself with an inadequate number of mostly obsolete weapons. American industry possessed the manufacturing capacity to make tanks, ships, and aircraft, but it needed time to retool for wartime production.

The knowledge required to build these armaments was also in short supply. For instance, while automobile makers could easily reconfigure their assembly lines to turn out jeeps and trucks, the manufacture of such uniquely military hardware as cannon barrels was another matter. No civilian firm then possessed the know-how necessary to fabricate an artillery piece.

Expanding the Watervliet Arsenal

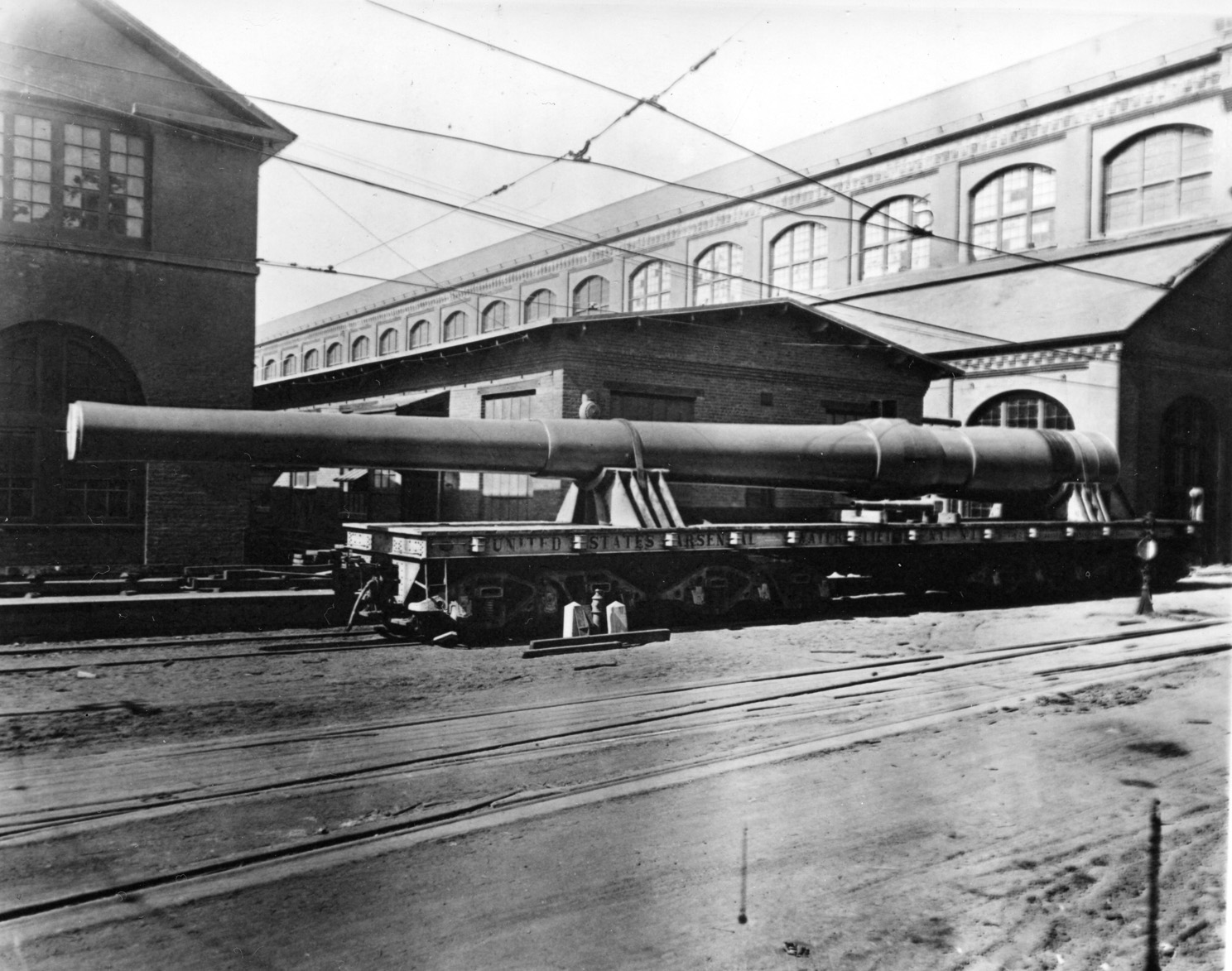

Fortunately, this specialized manufacturing knowledge resided in a system of government operated arsenals. One such plant, the Watervliet Arsenal, was the U.S. Army’s sole cannon factory in 1940.

Located on a 142-acre site eight miles north of Albany, New York, the Watervliet Arsenal had been building big guns since 1889. During World War I, 5,126 craftsmen worked there, manufacturing heavy artillery for the U.S. Army and Navy. Postwar downsizing, however, left a mere 321 skilled machinists on duty as of mid-1937.

Things began to turn around when, in November 1938, Colonel Richard Somers took command of Watervliet Arsenal. A forwardthinking officer, Somers correctly saw World War II coming and was determined to prepare for it. First, the arsenal received a facelift. A $24,750 Works Progress Administration project saw several old factory buildings reconditioned while the installation of new machinery promised increased manufacturing efficiency.

Colonel Somers then began expanding the workforce. By July 1939, Watervliet Arsenal’s personnel roster had grown to over 1,000 employees. One year later its staff had swelled to 1,752. By December 1941, over 3,000 people worked there.

Recognizing the need for skilled craftsmen, arsenal leaders opened an apprentice school in August 1939. This three-year course graduated expert machinists capable of making everything from 37mm antitank cannons to massive 16-inch naval guns.

High salaries attracted many to work at the Watervliet Arsenal. In 1940, a machinist’s daily wage was $6.96, while a mechanic’s helper earned $4.72 per day. Toolkeepers made $1,260 a year, and inspectors took home salaries of $2,300 annually. This was good money indeed for Americans accustomed to Depression-era pay.

In July 1940, Colonel Somers was replaced as commanding officer by Brig. Gen. Alexander G. Gillespie, the first and only general officer to command Watervliet Arsenal. Gillespie immediately directed the arsenal to adopt a 48-hour work week, which he deemed necessary to handle the increasing volume of orders from a rapidly expanding military.

The Arsenal at War

The nation had just authorized its first peacetime draft when President Roosevelt visited Watervliet Arsenal on October 7, 1940. Escorted by General Gillespie, Roosevelt observed cannons being forged in the bustling Big Gun Shop. While the United States was not yet at war, the workers at Watervliet were getting ready for one—and so was the president.

When Japanese planes struck Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the arsenal’s workforce was enjoying a Sunday off. Ernie Blanchet, an inspector from Troy, New York, was at his sister’s house when he heard the news. “I remember thinking that maybe the arsenal was going to be a target,” he said, “because of the important work we were doing to help prepare our country for war.”

The next day, Blanchet recalled, “Lines of cars, as well as workers, were backed up as security guards checked every vehicle and person coming into work.” To make it in on time, Ernie and hundreds of other employees jumped the arsenal walls rather than wait at the gate. Special security badges later speeded entry for the thousands of war workers employed there.

Watervliet Arsenal’s expansion accelerated with the declaration of war. In December 1941, Gillespie announced construction of a tank repair center. By August 1942, it was open and overhauling war-weary combat vehicles. New warehouses and a modern cannon factory also went up at a rapid pace.

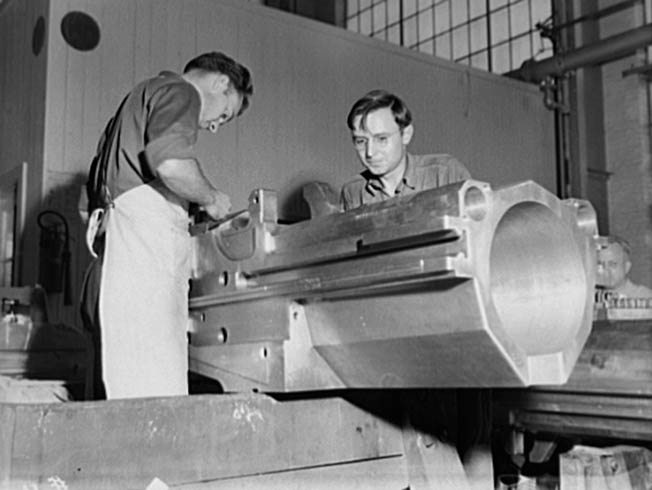

Arsenal employees began traveling across the United States to help private companies start up their own gun factories. Standardized manufacturing procedures developed at Watervliet resulted in near 100 percent interchangeability among U.S.-made cannons.

All the while Watervliet Arsenal kept busy filling orders. In December 1942, the factory delivered 1,294 37mm barrels, 954 75mm cannons of various types, 209 3-inch antitank guns, and 270 90mm antiaircraft tubes. Largebore production that month included 49 155mm, 14 8-inch, and two 240mm howitzer barrels.

Women Ordnance Workers at Watervliet

This unprecedented growth left Watervliet Arsenal facing an acute labor shortage. Many experienced workmen had either been drafted or volunteered for military service, and General Gillespie refused to grant Selective Service exemptions except to those deemed “practically indispensable.” During the war 2,600 arsenal employees would enter the armed forces, draining Watervliet’s gun shops and repair depot of experienced workmen.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, the arsenal began hiring women to replace departing male employees. By December 1942, a total of 2,905 females—31 percent of the total workforce—held jobs there.

Women Ordnance Workers (WOWs) filled a variety of positions at the Watervliet Arsenal. Supervisors found them well suited for almost all manufacturing and repair work. Following a three-week training course, female “mechanic learners” began operating drill presses, milling machines, and hydraulic cutters—often with remarkable skill.

The WOWs fit in well. Of Jean Wiorek, a 22-year-old machinist from Albany, one shop foreman remarked: “She’s picked up amazingly fast and now can turn out a reamer as perfect as any toolmaker ever could.”

Other women repaired tanks or helped run the unheated Field Service Depot, nicknamed “Siberia.” There, workers ran three shifts six days a week packaging and shipping repair parts needed by Allied armies around the world.

Women took jobs at Watervliet for a variety of reasons. One 18-year-old from Troy, New York, named Maureen Stapleton briefly worked there as a typist in 1943. Stapleton’s goal was to earn $100 so she could move to New York City and study acting. This she did, later embarking on a 57-year career in show business that would earn her Tony, Emmy, and Oscar awards.

“Commandos” and Returning Workers

As private industry took on the manufacture of small-caliber cannons in 1943, the Watervliet Arsenal shifted its focus to big gun production. The Army required more large-bore 155mm, 8-inch, and 240mm cannons, which meant a new mission for the arsenal. It also put new strains on the workforce. Watervliet Arsenal responded by hiring 200 “commandos”—high school students, homemakers, and people employed elsewhere—for work six evenings a week plus full shifts on Saturday and Sunday.

The arsenal got another boost when 51 former workers returned to Watervliet wearing the uniforms of privates in the United States Army. In many cases, these servicemen went right back to their previous jobs as machinists or toolkeepers. The most noticeable change was in their salary—as skilled civilian technicians they brought home over $200 a month, whereas an Army private made less than one-fourth of that amount.

49,052 Cannons Assembled

The WOWs, commandos, soldiers, and civilian employees at Watervliet Arsenal worked hard to meet the Army’s demand for heavy artillery. From July 1943 to May 1944, Watervliet’s gun factory turned out 9,888 cannons with an on-time completion rate of 99.5 percent. In one month, November 1943, the arsenal made more guns than it did during all of World War I.

These accomplishments did not go unrecognized. In a ceremony held September 30, 1942, the Army-Navy Production Board presented the employees of Watervliet Arsenal with the first of five “E” (for excellence) awards they would eventually win. Each worker received a pin and the Production Award pennant was flown on an arsenal flagpole. Then everyone went back to work.

The surrender of Japan brought with it a return to normal routines at Watervliet Arsenal, yet the workforce could take great pride in its wartime record. From 1940 to 1945, Watervliet’s workers assembled 49,052 cannons at a total cost of $260 million. At its peak the arsenal employed 9,332 men and women.

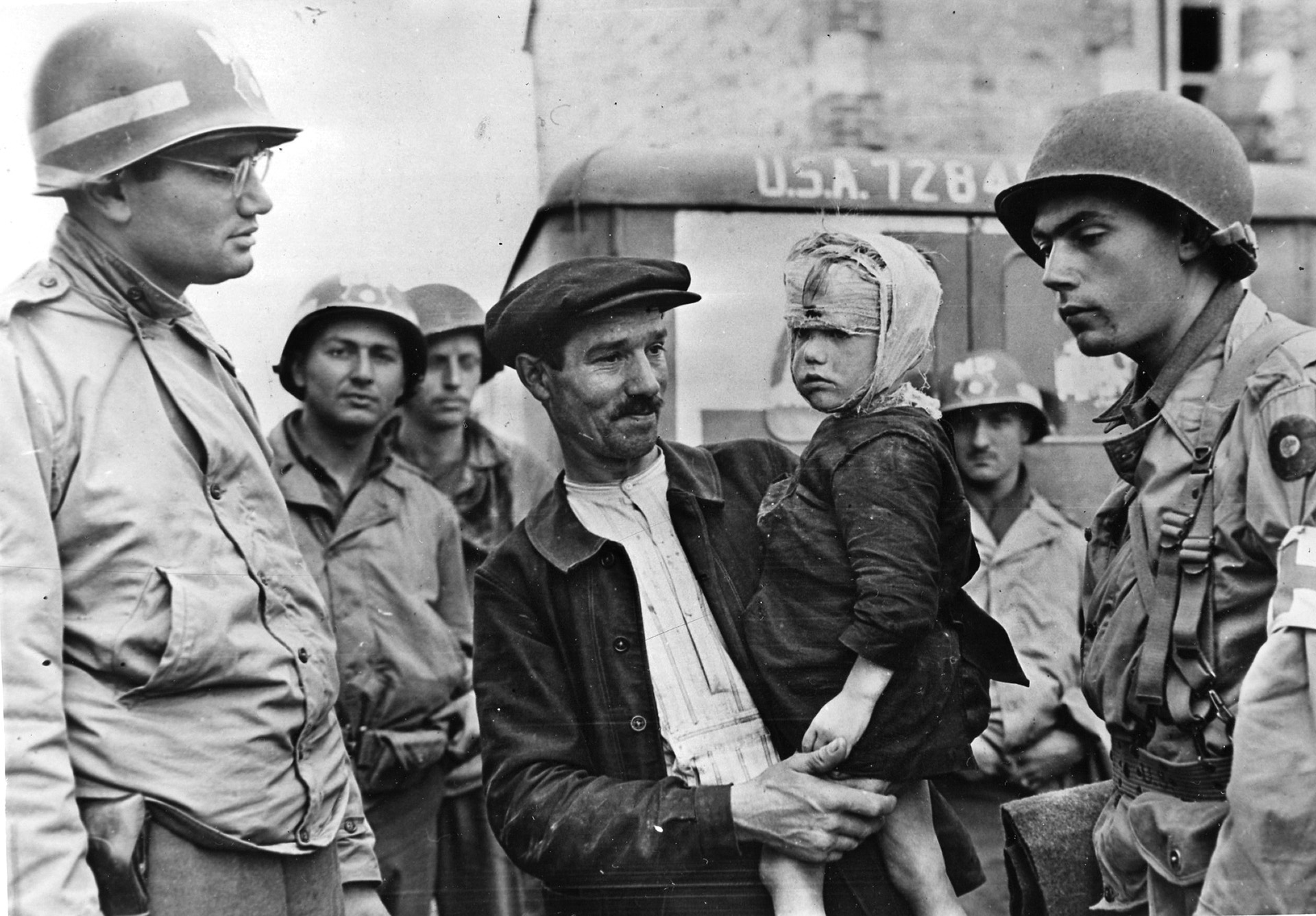

The miracle of production that occurred at installations such as Watervliet Arsenal transformed America into the great Arsenal of Democracy. The guns built there won victory on every battlefront of World War II. Today, Watervliet Arsenal continues its proud manufacturing tradition as the United States’ premier cannon factory.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments