By Robert Heege

The year was ad 678, 46 years after the death of the prophet Mohammed. Now the Mohammedans, determined to bring the light of Islam to Arabia and beyond, were streaking across the whole of the Middle East like a comet. Their statecraft, as it turned out, was as basic and unyielding as their faith. Those who would not answer the call of the muezzin would be treated, instead, to the sword.

For years, the Muslims had successfully managed to nibble at the borders of the Byzantine Empire. In turn, first Lebanon, and then Syria were lost, absorbed forever into the Arab world. By the early 670s they were ready to start westward. Working their way across the Anatolian peninsula in what is now Turkey, the Arab forces were relentless, insatiable, and seemingly unstoppable. With their sights firmly fixed on the West, the Saracens (from the Greek Sarakenoi, a corruption of the Arabic word Sharqiyun, meaning “Easterners”) began gobbling up bits and pieces of territory, as they edged ever closer to the real prize: Constantinople.

Emboldened by their seizure of Kyzikos (Cyzicus), an ancient Greco-Roman seaport on the Sea of Marmara (now Balikhisar, Turkey), they set about transforming the sleepy little outpost into an impressive naval base bristling with ships, each packed with a mighty Muslim host, ready to take on the Christian infidel on his home turf. The stakes could not have been higher, for by striking at Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, they would be aiming directly at the heart of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

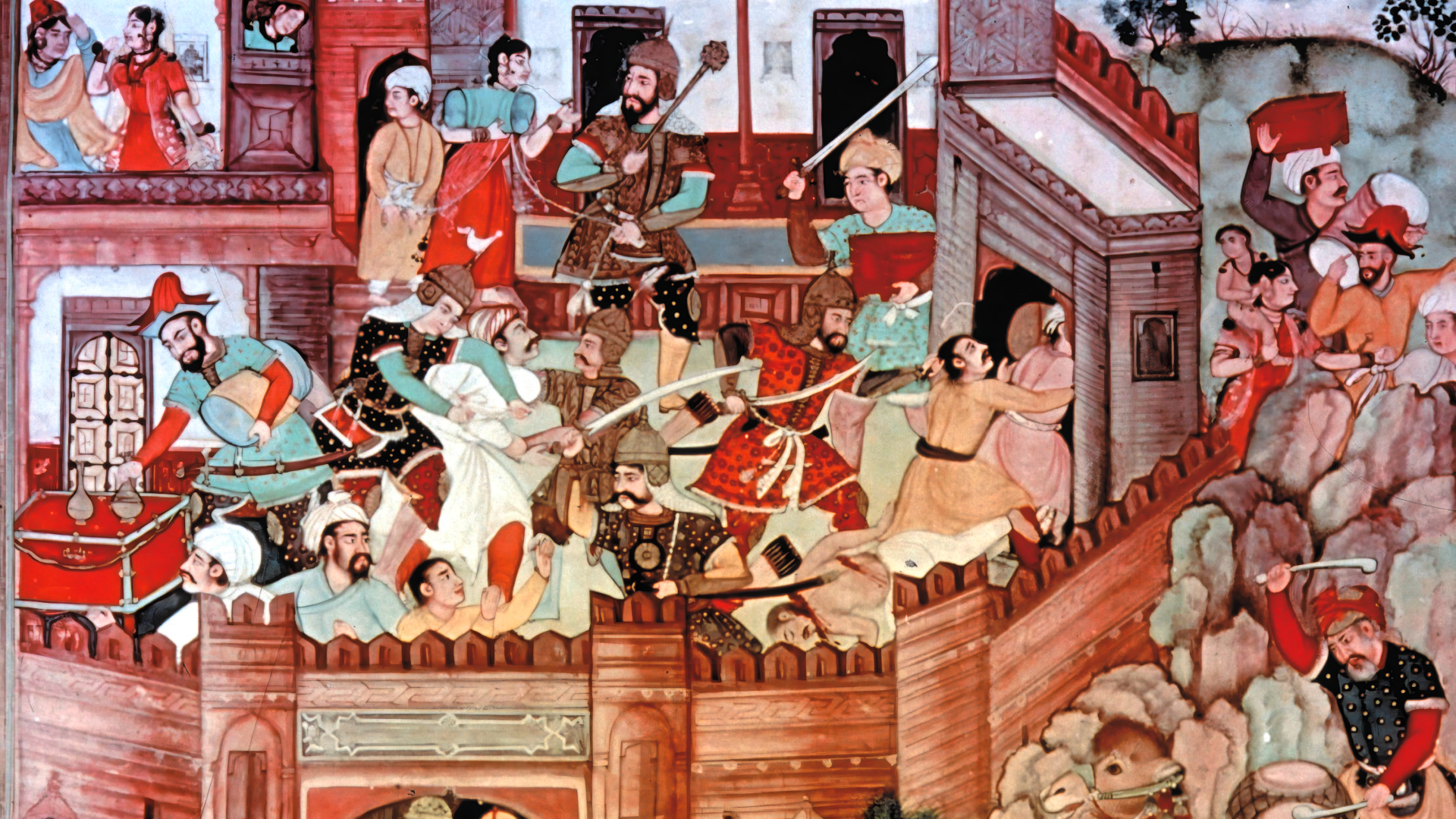

Flush with visions of victory, the enormous Saracen fleet hoisted anchor and set sail from Kyzikos. Moving across the water like a seaborne dagger, they hugged the coast and were soon within sight of their goal, heading directly toward the storied walls of Constantinople. With the rays of the eastern Mediterranean sun shining and the glistening towers of the fabled fortress-city beckoning before them like a mirage, it must have seemed to the Saracens as if Allah himself was smiling down upon them, ready to reward their zeal with the heavenly seal of victory. Before the sun would set that day, however, many a Muslim soul must have wished that they had never left the harbor.

Catching sight of the numerically inferior Byzantine navy, which could now be seen gamely sailing out to meet this threat, the men of the mighty Islamic armada must have been convinced that this jihad was going to be a cakewalk. If indeed any of them even noticed the single bronze tubes jutting out from the prows of each of the Byzantine ships, they paid them no mind. They were about to receive the surprise of their lives.

As the Byzantine ships drew closer and closer, looking like nothing so much as sheep coming to the slaughter, the Saracens, far from being concerned, drew themselves up and prepared, no doubt with great relish, to pound the tiny flotilla into splinters. Then, something extraordinary happened, something never before seen in the history of warfare, for it was the Saracens, and not the Byzantines, who went to the slaughter.

Suddenly, from out of the mouths of those innocuous-looking bronze tubes came the dragon’s own breath, pressurized jets of liquid fire that shot across the water in short, volcanic bursts, immolating soldier, sailor, and ship’s timber alike. The flames, which literally engulfed everything they came into contact with, could not be extinguished. Like modern napalm, these flames stuck to everything they touched. The hapless Saracens ran about the flaming decks burning like Roman candles. Those who fell overboard, or in their unspeakable agony threw themselves over the side, found that even this was not enough to staunch the flames. Instead, the afflicted men continued to burn in the water, their blackened bodies bobbing around in the sea like so many cloves of burned garlic.

As the Byzantines directed the blasts of liquid fire onto the surface of the water, the sea itself caught fire, erupting into sheets of flame that roasted men alive, even as they swam for their lives in mortal terror. For the Saracen fleet, there was neither victory nor escape as one by one their ships were transformed into floating bonfires, burning hulks that slipped, smoldering, beneath the waves. To the Saracen host who died that day, it must have felt as if the very fires of Hell had been unleashed against them. God, it seemed, was not on their side after all.

This was Islam’s—and the world’s—first introduction to that most awesome and mysterious weapon of the Byzantines: Greek Fire.

In and of itself, of course, the many destructive ways in which fire can be put to use was actually nothing new, even to the world of ad 678. Its use is as old as war itself. Scenes depicting fire in battle have been found on Assyrian bas-reliefs. The Egyptians also used fire, as did the ancient Greeks and the Romans. Over the centuries, a variety of concoctions containing some combination of sulfur, bitumen, rosin, naphtha, pitch, charcoal, tallow, turpentine, saltpeter, and crude antimony would all make their appearance on the battlefield. In naval warfare, wooden and clay pots filled with these volatile mixtures were set alight and either thrown or catapulted onto the decks of enemy ships. True Greek Fire, however, as the Saracens discovered in 678 and again in ad 718, when a second massive invasion fleet met the same grisly fate as the first, was an entirely different animal altogether.

True Greek Fire was a “wet fire” that could be concentrated, controlled, and directed at will with all the destructive force of a modern flamethrower of the sort used by American marines in the South Pacific during World War II. For the warriors of the 7th century, however, and of the next several hundred years, the awesome destructive power of Greek Fire—and of its psychological impact on the enemies of Byzantium—would have been equivalent to that of a modern atomic bomb.

According to the historian Theophanes, the inventor of this Byzantine form of “nuclear” warfare was a brilliant architect and engineer named Kallinikos (Callinicus). Kallinikos, who was Jewish, was a loyal subject of the Byzantine Empire from Heliopolis (present-day Maalbek) in Syria. Forced to flee his homeland following the Arab conquest of Syria, Kallinikos made his way to Constantinople and offered his services to the Byzantine Emperor, Constantine Pogonatus. The Emperor wisely accepted.

Beyond that, almost everything else about Greek Fire is a mystery. Even the name is something of a misnomer. Called “Sea Fire” by the Byzantines themselves, it was called “Roman Fire” by the Arabs, because the Byzantine Empire was the successor state to the Eastern Roman Empire. The term Greek Fire comes down to us courtesy of the Crusaders, who rampaged their way through the eastern Mediterranean during the Middle Ages. The Crusaders dubbed it Greek Fire because they thought of the Byzantines as Greeks—this confusion being, no doubt, engendered by the fact that the preferred language of the Byzantines was, like its culture, not Latin, but Hellenistic Greek. Paradoxically, by virtue of their ancient pedigree, the Byzantines never stopped thinking of themselves as Romans.

What is known is that Greek Fire was used not only on Byzantine warships but was also deployed from the walls of Constantinople itself, enabling the Byzantines to successfully defend the city from attack on numerous occasions over the course of several centuries. According to scholars, Greek Fire was most likely a mixture of sulfur and a form of distilled liquid petroleum similar to gasoline that was thickened with resins (possibly tree sap), which gave Greek Fire its adhesive qualities. It is also widely believed that quicklime was one of the distinguishing ingredients in the formula for true Greek Fire, because a key property of this substance is the large degree of heat produced when it comes in contact with water.

The best evidence suggests that it was stored in large vats and projected through narrow bronze tubes with a kind of force pump said to have been invented by the Greek inventor Ctesibius. This would account for the fact that the weapon was only capable of discharging in short bursts, rather than in a continuous, prolonged stream of fire. The tubes pressurized the liquid mixture, concentrating it into a narrow jet of fluid in much the same manner as the nozzle on a garden hose does with water. Then, as the liquid emerged from the end of the tube, it was ignited by some kind of fuse. The result was a stream of fire dozens of feet long arcing through the air.

The exact details of Greek Fire’s deployment, like the actual formula itself, are destined to remain a mystery. The secret “recipe,” which was never written down, was a jealously guarded state secret that was known only to Kallinikos and his family, who alone prepared the mixture, and to the emperors of Byzantium, who were said to hand the secret down to their heirs from generation to generation. After 718 it was used only in the direst of emergencies, lest the secret of its power fall into the hands of their enemies. For many years its fearsome reputation apparently proved to be enough of a deterrent to discourage most would-be conquerors. Incredibly, the formula for true Greek Fire appears to have been lost. Eventually, the Byzantine Empire itself was lost. The great walled city of Constantinople, however, continued to endure, finally falling to the Turks in 1453, a victim of another “wonder weapon” that remains with us to this day—gunpowder.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments