By Stephen D. Lutz

Thousands of Japanese American men demonstrated their loyalty to the U.S. by volunteering to serve in the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Infantry Regiment, to which the 100th would later be joined. Comprising almost entirely Asian Americans, the 442nd would become the most decorated group of its size in the history of the U.S. military.

For young American men of Japanese descent, getting into World War II was not easy. Distrust by whites of anyone who looked Asian was rife. And if war with Japan broke out, many government and military leaders wondered: On which side did the loyalties of these Asian Americans lie?

Among Japanese Americans, there were three classes: Issei (born in Japan but moved to the U.S. or its territories), Nisei (born to Issei in the U.S. or its territories), and Kibei (a person of Japanese descent, born in the U.S. but educated in Japan).

To prepare for a possible war, on October 15, 1940, the Territory of Hawaii (it would not become a state until August 21, 1959) established its 298th and 299th Infantry Regiment Territorial Guard units. Of approximately 3,000 members, about half were Hawaiian-born Nisei. Military induction and basic training were performed at Schofield Barracks on Oahu.

The Hawaiian Army Department commander, Lt. Gen. Charles Herron, was quoted in 1940 as saying, “The Army is not worried about the Japanese in Hawaii. Among them there may be a small hostile alien group, but we can handle the situation.

“It seems people who know least about Hawaii and live farthest away are most disturbed over this matter. People who know the Islands are not worried about possible sabotage. I say this sincerely after my years of service here. I am sold on the patriotism and Americanization of the Hawaiian people as a whole.”

As Herron noted, those living the farthest away (i.e., the War Department in Washington, D.C.) were the most disturbed. Besides the issue of Asian Americans, the top brass of the armed forces did not want to upset the status quo with regard to African Americans, either, fearing that integrating the services would promote disharmony and light the fuse of a racial powder keg.

A major concern was that white troops would not obey the orders of an officer or NCO of color. Curtis Munson, President Franklin Roosevelt’s personal advisor, felt the same as Herron and wrote, “The army officers confessed that they held their breath. Much to their surprise and relief, there was absolutely no reaction from the white troops, and they liked these officers very well…. The Army is going to try more.”

Joining up

The parents of Isaac Fuko Akinaka were born and raised in Japan but immigrated to America to become naturalized citizens; Isaac was born in Honolulu in 1911. In spite of his Japanese heritage, he was American enough to prefer the name “Isaac;” he joined the Hawaiian 298th Infantry Regiment Territorial Guard on December 9, 1940, at age 29.

A year later, Pearl Harbor changed everything, forcing many young men to make life-changing decisions. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor the weekend before he was to be discharged, Isaac Akinaka said, “The war has come upon us.” He extended his military service.

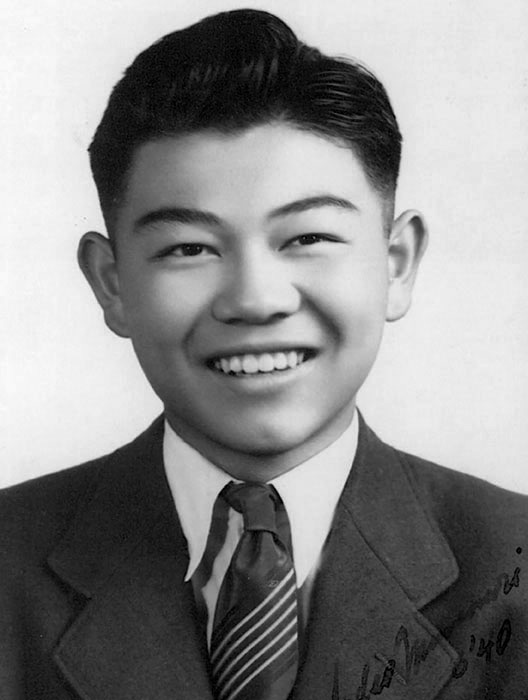

Honolulu resident Daniel K. Inouye, age 17, was getting ready for church that Sunday and heard the radio announcer frantically repeating that Pearl Harbor was under attack by the Japanese. Inouye and his father rushed outside. “We looked towards Pearl Harbor and puff! All the smoke. And you could see puffs of the anti-aircraft shells exploding. And then, all of the sudden, three aircraft flew right over us—green color with the red dot in the wing. I knew my life had changed.” Inouye, a high school senior, rushed to a Red Cross aid station to help civilians and sailors wounded in the attack.

Inouye tried to enlist after graduating from high school in 1942, but the U.S. had closed all new enlistments to men of Japanese descent. Thus barred, he enrolled at the University of Hawaii as a pre-med student. But he soon learned of the formation of the all-Japanese American 442nd Infantry Regiment; he quit school and volunteered, and was assigned to Company E, 2nd Battalion. He would become one of the most highly decorated members of the 442nd.

Despite personally feeling that Japanese Americans did not pose a security threat, Roosevelt was pressured by Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt head of the Western Defense Command into issuing Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942—the order that established internment camps to which Japanese Americans, most of whom were full U.S. citizens, were sent for the duration of the war.

Some 110,000-120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, most of who lived along the Pacific Coast, were forcefully relocated to 10 detention camps farther inland, where they would live behind barbed wire and be watched over by armed guards. (Interestingly, because the Issei and Nisei were so numerous in Hawaii, and their removal would have created such severe hardships to the islands’ economy, the government there chose not to relocate them.)

Frank Tadakazu Hachiya became Kibei in 1936. His Issei parents inherited a business in Japan, compelling him to travel there and oversee their affairs. He then attended a Japanese university for four years. Toward the end of his academic experience, a Japanese professor with high standing in the Japanese Army pressured him to stay in Japan, arguing that the Japanese Army was going far and Hachiya could advance with it.

Hachiya, however, saw great rifts between Japanese and American society, and he would always be American. When he died in action on January 3, 1945, it was with the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Service in Leyte Gulf.

Whether these Nisei and Kibei were born in the continental United States (CONUS) or Hawaii would impact their perspectives upon entering the Army. Their life experiences differed. The Hawaiians were halfway closer to their Japanese heritage and culture than those growing up in CONUS. The islanders spoke English with a smattering of Japanese and Hawaiian mixed in, a sort of pidgin English. In CONUS, the Nisei generation spoke a more traditional, purer English.

When these two sets of the Nisei generation met in places like Camp Shelby, Mississippi, conflicts arose due to their differences. At their first meeting, the name-calling started with the CONUS men calling the islanders “Buddhaheads,” due to their proximity to Japan and the heavier influence of Japanese culture in Hawaii.

The islanders retorted by calling the CONUS recruits “kotonk,” mimicking the sound a of a coconut hitting the ground after falling out of a tree—or the hollow sound of a CONUS Nisei head hitting the ground. Throughout the war, both insulting names were regularly heard.

Once the U.S. became involved in a two-front war, these soldiers had no idea what to expect. Thomas Taro Higa, for example, was Kibei, having been born in Hawaii but having gone to Okinawa to visit extended family, and then on to Osaka to study electrical engineering. He spoke Japanese and also the common dialect of Okinawa, known as Uchinaguchi.

Unimpressed with the police state that Japan was then becoming, Higa returned to Hawaii and joined the 298th in June 1941. When Pearl Harbor occurred, he originally thought the attack was a combined Army-Navy-Air Corps drill. Later he would say, “All the [Nisei] troops were thinking about the high expectations set upon our shoulders.”

Higa would serve with the 100th Battalion during combat in Italy and end up with two Purple Hearts; then it was back to CONUS for a speaking tour. From there, he ended up back in Okinawa with his trilingual skills, entering no fewer than a dozen caves alone to convince the island’s residents that the war was over and they could come out. He certainly met those “high expectations set upon [his] shoulders.”

Stateside training

After the great sea battle of Midway on June 4-5, 1942, a group of 1,432 Japanese American GIs of the 100th Battalion boarded the passenger ship SS Maui, destined for San Francisco Harbor and Oakland, California. The most entertaining aspect of the seven-day voyage was the rattling of dice in craps games, where the words “go for broke” were heard regularly. It would become the unit’s battle cry.

Upon arrival in Oakland, the 100th was divided into three trainloads and immediately all headed to Camp McCoy in Sparta, Wisconsin.

Camp McCoy, halfway between Milwaukee and Minneapolis, was an unusual setting for the 100th, where they repeated the same 13-week basic training that they had already completed at Schofield Barracks. Within the 45,000-acre site was a corner for prisoners of war—Germans, Italians, and Japanese. In another corner was a relocation camp for West Coast Issei and Nisei.

All throughout World War II, this would be the only Army installation catering to all three segments of Japanese American citizens: civilian Issei, civilian Nisei, and GIs. On occasion, unfortunate events were bound to happen.

While at McCoy, Edward Mitsukado witnessed an event that had the potential of turning into a mass shooting. One day a member of the 100th stormed into the barracks in rage. This Nisei soldier had passed by the internment camp and seen his father inside, behind barbed wire and beneath guard towers, with guards’ guns pointing inward, and not at port or shoulder position. Father and son were prohibited from speaking to one another through the wire enclosure, with the father never acknowledging his son’s presence.

So, seething with rage was this soldier, Mitsukado believed him capable of acquiring a rifle to go on a shooting spree. Mitsukado consoled him at length, telling him that the best way to help his father, and himself, was to do his job as an American soldier with honor and prove to others that people like his father needn’t be penned in. All that talking soaked in, and the soldier calmed down.

Sparta’s populace of 6,000 was receptive to these neighbors. Lingering resentment about Pearl Harbor never fully dissipated, but the town was generally welcoming enough to overlook such sentiments. The Hawaiians saw their first snow and ice skates at a skating rink, where Army jealousies also arose.

According to Irving Akahoshi, the only real trouble at McCoy came when the 2nd “Indian Head” Infantry Division arrived from Texas. It seemed that the 2nd was “brainwashed … indoctrinated” to hate all things Japanese; Akahoski said that brawls with the Texans were frequent. Worse yet, the local ladies preferred the company of the Hawaiians more than that of the 2nd as social events like dances and skating parties became more common.

A nearly fatal event in the winter of 1943-44 particularly helped cement relations with the civilians. A small group of local residents fell through the thin ice covering a lake. A nearby gathering of 100th Battalion GIs rescued the victims, saving them from drowning. Civilian-military relations could not have been better.

At McCoy, the 100th put together a traveling baseball team called the “Aloha Team,” playing within Camp McCoy and then across Wisconsin against amateur and semi-professional teams.

The team’s first baseman was Yoshinao “Turtle” Omiya of Hawaii, who got his nickname as his high school’s catcher, covering home plate “like a turtle shell.” (He would be blinded by a German mine while crossing the Volturno River in Italy.) By war’s end, the Aloha Team had seen six players killed in action with just as many wounded.

The 100th lost 67 GIs when they were transferred to Camp Savage, Minnesota, for Military Intelligence Service training. Given their scores on the military aptitude tests, these men were selected for their excellent bilingual Japanese-English skills.

Among those transferred was Sergeant Edward Mitsukado. One day a team from Camp Savage came to Camp McCoy to administer language comprehension tests to his group. Mitsukado insisted that he comprehended very little Japanese, but he ended being picked anyway, much to his displeasure. When he asked about being selected despite his lack of knowledge of spoken Japanese, he was told that he was primarily chosen for his excellent English.

After six months at Camp Savage, Mitsukado ended up in the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations within the 5073rd Composite Infantry, more commonly known as Merrill’s Marauders.

Of the 66 other Camp Savage men, some went ashore at Bougainville, New Guinea, Guam, and Okinawa as interpreters and interrogators of Japanese POWs. Some became decoders, not only in the Pacific Theater of War but also in China-Burma-India, Washington, D.C., and London.

One decoder was Harold Fudenna of Irvington, California. On April 16, 1943, Military Intelligence in Bougainville obtained a coded Japanese message that they knew included the words “Admiral Yamamoto.” (Isoroku Yamamoto was the mastermind behind the Pearl Harbor strike.) Fudenna translated the coded message into English. Two days later, Admiral Yamamoto was shot down over Bougainville.

Off to the Deep South

For their departure from Camp McCoy, the 100th put together a traditional Hawaiian luau party for the residents of Sparta. Their next destination, Camp Shelby, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, offered less reason to party. On January 6, 1943, they were off to the racist realities of America’s Deep South.

When the 100th arrived at Camp Shelby, they entered a world they had never seen before. In terms of its military populace, Camp Shelby was among three of the largest bases in America. Like all things “Southern” in that era, it had its authority, rules, regulations, and traditions geared to a particular “Southern” orientation.

This entailed the old, unwritten code of a caste society, with racial prejudice and discrimination ingrained and unchallenged for centuries. The leader of this pack was that mythical figure known as “Jim Crow.” For the first time in their lives, the men from McCoy saw signs at water fountains, restrooms, and restaurants stating, “Whites Only” or “Colored Only.” Nobody knew which category “Nisei” fell under. Certainly, nothing existed as “Asian Only.”

For much of the civilian populace of Hattiesburg, these were their first encounters with Japanese Americans or Asians in general.

In February 1943, an oddity showed up before 100th Battalion commander Lt. Col. Farrant Turner in the form of Young Oak Kim. Kim was born in a Los Angeles neighborhood with a mixture of Japanese, Chinese, Mexican, and Jewish residents, while Kim himself was Korean.

Enlisting in the Army in January 1941, Kim took the opportunity to attend officer candidate school. At Camp Shelby, Lt. Col. Turner tried to talk Kim into seeking a reassignment outside of the 100th for what he thought was an obvious reason: Japan had invaded Korea in 1910, and there, Japanese imperialism remained to dominate, murder, plunder, and rape in Korea until the war’s end.

Turner thought that Kim would be uncomfortable in the 100th, but Kim said, “You’re wrong. They’re Americans, I’m American, and we’re going to fight for America.” Turner kept this second lieutenant.

It took a while, with a few challenges and occasional head-butting, but the 100th eventually accepted Kim. He instituted training routines and tactics at Camp Shelby that would eventually be implemented Army-wide. In time, the 100th/442nd gave Lieutenant Kim the nickname “Samurai Kim.”

Not all White Southerners treated the Japanese Americans poorly. After the 100th left Shelby for Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, the newly formed and enlarged 442nd Regimental Combat Team moved into Shelby in May 1943. On a weekend pass, four GIs of the 442nd stared longingly at the civilian clothes in the window of a clothing store owned by 27-year-old Earl Finch.

Finch befriended them and invited the group to come home with him so that his mother could prepare dinner. Finch had done this many times for Shelby GIs, the pattern being that a small number of GIs would take him up on the offer, show up, eat, leave, and then never be seen again. Such was life around Camp Shelby.

These Japanese American GIs from the 442nd, however, returned the very next day with flowers for Finch’s mother. As Finch came to know these Hawaiians, his admiration grew, especially upon learning how many had voluntarily enlisted straight out of the internment camps, which few white Americans even knew existed.

Finch went so far out of his way for these men that he eventually purchased a 350-acre ranch and converted it into an improvised USO facility, organized swimming and baseball teams, and arranged for travel to and from games and swim events.

The new home of the 100th, Camp Claiborne, in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, had the primary task of providing conditions for supervised war games at division levels. The 100th slogged through terrain that was as bad as that of any upcoming battlefield in Europe or the Pacific. Units of all sizes were combined here and umpired and scored on the tactics imparted to them for 10 months. Once again, the 100th performed far above expectations.

By the beginning of June 1943, the 100th was back at Camp Shelby, where the 442nd was encamped. Among the 442nd was Norman Saburo Ikari, a late arrival. At the time, he had immediate and extended family members in the relocation camps of Colorado, Arizona, and eastern California. One brother, a long-time Colorado resident, had evaded such fate by not being a West Coast resident.

Rivalries

At Camp Shelby, Ikari saw the regional attitude differences between islanders and “kotonks.” The slightest petty jealousies became full-blown shouting matches that could rapidly escalate into brawls and injuries. Ikari said that the situation dissolved into his Company E posting guards against Company M. Since live ammunition was out of reach, these guards stood by with fixed bayonets.

Battalion leadership finally attempted a resolution by inviting a convoy of soldiers from both factions on an outing. At first, the men thought it was another extended touristic trip. Instead, it was a five-hour ride north to the Rohwer Relocation Camp in Arkansas.

For those men who had never seen a relocation camp, both those from Hawaii and some “kotonks,” it was a shock. They saw the flimsy, tar-papered, plywood makeshift housing in which their fellow Issei and Nisei American citizens were incarcerated. They entered through locked, monitored gates, with barbed-wire fences and towering guard posts with machine guns and rifles pointed inward.

As for the residents of the camp, the doors of their homes were as wide open as could be. Families struggled to serve as splendid a meal as they could on limited food rations. The camp, being a pseudo-military environment, some of the visitors dined in the community mess hall, where meals served were not nearly as good as what would be seen in a soldier’s mess hall. Some of these soldiers were so ashamed and saddened that they described feeling as if they were stealing the meals doled out for someone else.

With a similar visit planned for the camp at Jerome, some GIs took up sleeping in the back of a deuce-and-a-half rather than intrude on the small quarters in which these families lived. Returning to Camp Shelby, a new attitude could be seen among the men of the 100th and 442nd. They became the unified fighting force that history would soon know them—fighting an American war to save those Americans who were locked away.

Then came the military custom of receiving one’s “colors,” or unit flag. Army officials had the audacity to suggest that the 100th’s flag motto be “Be of Good Cheer.” This was unfathomable to the 100th; it took perseverance, but they got the wording changed. Being mostly Hawaiian and witnesses to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the three words “Remember Pearl Harbor” were inscribed upon the flag of the 100th.

A time for war

On August 21, 1943, the 100th boarded the transport ship SS James Parker out of New York Harbor for an 11-day voyage to an unknown destination. On September 2, the 100th stepped ashore at Oran, Algeria, the home of the 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division, and became a battalion within the 133rd Infantry Regiment, destined for an assault upon Italy’s Salerno beaches.

The first landings by the 34th commenced on September 19, with the 100th arriving once the beachhead was secured. The first job given to the 100th was to temporarily guard an airfield and a fuel storage depot. Four days later, they came to see the real meaning of war.

On September 23, the 100th began moving inland from Salerno along a windy, curvy road, going uphill into thickening woods. The twists and turns were so sharp that they could not see around bends to know what lay ahead, but they knew that the farther they proceeded, the more likely enemy contact was.

Coming around one such a bend, they came under enemy machine-gun fire, then mortar rounds and finally artillery. Recoiling from the initial incoming shots, Sergeant Shigeo “Joe” Takata announced: “It’s the first time, so I’m going first.” Going around the bend, he drew enemy fire, revealing the precise location of a German roadblock.

While his Company B outmaneuvered the enemy’s position, Takata was hit and killed by shrapnel; he became the first of hundreds of Japanese Americans to be killed in action. By the end of that day, one more would be killed in action and seven wounded.

In March 1944, the 34th (and 100th Battalion) arrived at Anzio. Weeks of being constantly shelled and attacked awaited them. In May, as plans to advance upon Rome, 40 miles away, were being finalized, Captain Young Oak Kim and Pfc. Irving Akahoshi volunteered to crawl out onto exposed ground before sunset to see if they could corral a German prisoner and obtain information about German positions and capabilities.

In fact, they brought back two Germans, one of whom was so informative that he revealed that no Panzer units existed where Clark wanted to penetrate the line going into Rome. With that knowledge, the planned assault on Rome was carried out unaltered, the city was captured, and Kim received the Distinguished Service Cross.

On May 28, 1944, the 442nd, minus its 1st Battalion—which remained at Camp Shelby as a cadre-training unit—arrived in Italy and was reunited with the 100th Battalion at Civitavecchia, north of Rome. On June 11, the combined unit was assigned to support the 34th Division.

Two weeks later, the Nisei unit went into battle at Belvedere in Tuscany. In a fierce engagement, the 442nd made a good account of itself, with the 100th, as the 1st Battalion was now known, earning a Presidential Unit Citation.

The fighting—and heroism—continued. Starting on July 1 and lasting for the next three weeks, the 442nd, under Colonel Charles W. Pence, was in constant combat. Advancing toward the Arno River, the 442nd captured Cecina and moved on to Hill 140 and Castellina, where it engaged in more pitched battles. On July 25, when the 442nd reached the Arno, German resistance suddenly collapsed, and the men were given a brief respite. A new assignment was in their future.

In Italy, the 100th/442nd had suffered 1,272 casualties—239 killed, 972 wounded, 44 non-combat injuries, and 17 missing.

At the insistence of the 100th, and with the approval of the 442nd, their hybrid unit became the newly reorganized 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team, effective August 14, 1944. Officially incorporated into the 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division’s 133rd Infantry Regiment, the 100th/442nd spent the rest of their time in Italy wearing the “Red Bull” division patch.

Invading France

On August 15, 1944, Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army invaded Southern France in Operation Dragoon. One of the participating divisions was the 36th “Texas” Infantry Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. John E. Dahlquist; in September 1944, the 100th/442nd was transferred to the 36th Division.

By personality, Dahlquist was such a hurried thinker that he rarely integrated military intelligence data into his far-fetched operational plans for his 141st, 142nd, and 143rd Infantry Regiments. His trend was to haphazardly rush into confrontations, never knowing who or what he faced or how many opposing soldiers might be present. Critics said that it was not unusual for him to show up in the middle of front-line action just to get in the way of everything and disrupt it all by demanding changes on the spot.

In late August, at the French town of Montélimar, 100 miles north of Marseilles, Dahlquist prematurely attacked without ever properly preparing the division for the assault. The situation stalled, and the battle for Montélimar shifted needlessly back and forth. At one point, the Americans had withdraw, allowing the Germans to find Dahlquist’s battle plans—revealing the strengths, positions, and paths of other divisions. Only after great effort were Montélimar and the surrounding areas cleared of the German presence.

In late October came the fight for Bruyères, surrounded by four hills in the Vosges Mountain region and 30 miles northwest of Colmar. Perhaps ignoring his intelligence sources, or perhaps being stubbornly opposed to the opinions of others, Dahlquist told the companies of the 100th that there were no Germans inside Bruyères.

Dahlquist’s attack plan required the 100th to cover six miles uphill through a rain-slicked forest to reach their objective, mired in fog and mud. At some points, the fog dramatically hindered visibility. Proving Dahlquist wrong about the German presence, the 100th /442nd came upon acres of mine fields, which alerted the enemy to open up with mortar rounds, machine guns, artillery, and Nebelwerfers (six-barreled rocket launchers).

For Young Oak Kim, now the 100th’s operations officer, the situation became so intolerable that he purposely cut communications with Dahlquist’s radio headquarters. Kim found Dahlquist’s orders based on “wrong information,” calling them “crazy orders.” Kim knew war far better than Dahlquist could imagine. Taking the initiative, Kim took one hill, coming down with 100 prisoners, and then a second hill, netting another 50 captives.

Holed up in a house in Bruyères, Kim was tracking enemy activity from a window when MG-42 rounds splattered the building, wounding him. When he regained consciousness, he was laid out on a litter carried by German prisoners under guard through a maze of trees, seemingly lost. A band of Germans emerged, surrounding the guards, medics, and wounded, who then became prisoners themselves.

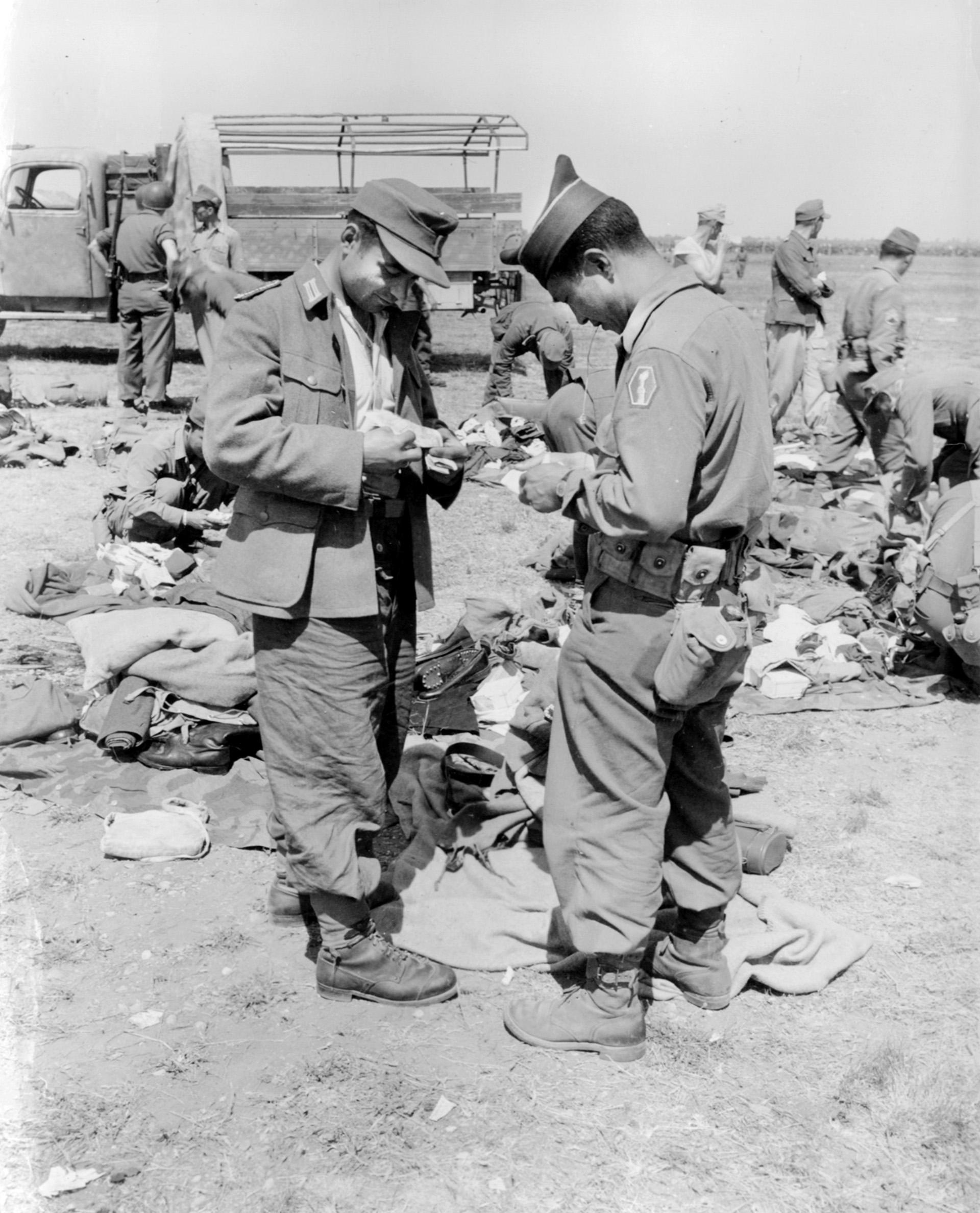

rescue the “Lost Battalion” of the 36th Infantry Division, October 1944.

Kim and a medic slipped into the woods unseen and eventually reached their own lines. In the end, Dahlquist withdrew everyone from Bruyères and the four higher hills, to which the Germans returned.

While Kim managed to slip out of this situation in Bruyères quickly, Jimmie Kanaya was not so lucky. Jimmie was a “kotonk,” born and raised around Portland, Oregon. When America’s conscription law went into effect on September 16, 1940, Kanaya saw a large number of his acquaintances being drafted. He decided to volunteer. At first Kanaya wanted to be a Marine, but they declined him. The Navy also said no but suggested that the Army took anyone. He never told anyone else what he was doing, so as not to become an embarrassment if not accepted anywhere.

Once in the Army, however, Kanaya was able to get into the Air Corps. Weeks after Pearl Harbor, he was abruptly reclassified as a medic without explanation. He was sent to an Army hospital, working alongside an Army nurse who taught him everything he needed to know about being a medic. He became capable enough to be acknowledged as the “ward master” in charge of the ward’s assigned medics. Thus, all of Kanaya’s medical training came via on-the-job-education. Twenty-five people within his hospital detachment of 300 were Nisei.

Having acquired immense knowledge and skills from the Army nurse with whom he had worked, he was promoted within the 442nd at Camp Shelby to second lieutenant in the Medical Service Corps. When he arrived overseas, the 100th/442nd was in France. Aligning with what Kim said of Dahlquist, Kanaya said that the difference in command lay in the personalities of each and their “theories” on how to conduct warfare.

No sooner had Bruyères been secured than Kanaya was called upon to send medics into Biffontaine, five miles east of Bruyères, to recover at least a dozen wounded GIs. Kanaya had no idea of how to proceed until a foot column lugging ammunition, rations, and supplies up to Biffontaine passed by. He followed them, which became an all-day trek across ridges and trees thick enough to be considered single-canopy jungle growth.

Upon reaching the injured with his three medics, he found seven litter-bound injured men and 10 walking wounded. A couple more were added by departure time at daylight. Needing a solution to carry seven litters three miles downhill, the obvious answer was the 35 prisoners of war on hand. Kanaya and his medics also attended to the injuries of the Germans no differently than they would for any of their own fellow countrymen.

Kanaya also distributed rations to the Germans, who reciprocated by finding straw for bedding material. These simple courtesies would be remembered by both sides.

For the next day’s journey downhill, the Germans helped carry litters as Kanaya’s group traded off carrying loads from time to time. Kanaya’s group of about 70 men included a few riflemen to guard the prisoners. On one of the stretchers lay Young Oak Kim.

There was no clearly marked path for the trek down, and the column was spread out nearly 200 yards along the line. At one point, the line halted and the straggling group bunched up at the front. Knowing the treacherous landscape and the roaming German patrols, Kanaya had his medics bring up the rear so that, if the front came under fire, they could flee into the trees with the wounded.

Those at the front then walked straight into a German patrol of 100 men who were as lost and adrift in the woods as the Americans. Luckily, the Red Cross flag carried by the point man prevented any firing. In fact, the first batch of Germans they crossed paths with initially wanted to surrender.

Their leader, a hard-core Nazi, interceded, and the tables were suddenly turned. The GIs at the end of the line could hear arguing: Who was surrendering to whom? Then the 35 Germans who had been escorted as prisoners began collecting weapons from those toward the rear of the column; GIs began giving up their weapons.

Just before that, however, two GIs bolted past Kanaya into the woods. They were Young Oak Kim and another medic making their successful escape. 2nd Lt. Jimmie Kanaya, however, became a prisoner of war. With everything reversed, the Nisei GIs now carried the occupied litters. As their former prisoners saw them tire, they switched off, relieving the Nisei.

Once in Biffontaine, the Nisei group was gathered together, and no one was robbed of any personal items such as watches, rings, or anything else of monetary value. That was how much respect these Germans had for Jimmie Kanaya and his crew. Any thefts or confiscation to occur would happen days later, further down the POW processing line, as Kanaya and others found themselves transferred to Oflag XIII-B at Hammelburg.

All in all, Kanaya tried to escape three times, being caught twice and giving up on the third as a useless attempt. Among his stories of POW experiences, he said that the first 100th officer to be taken as a POW was a second lieutenant in the very first weeks in Italy.

Once that man was delivered into the hands of the Germans, the Imperial Japanese Embassy in Berlin heard of a Japanese American being detained by the Germans. They arranged an interview with this lieutenant to hear how any Japanese individual, regardless of citizenship, could fight against the Axis. This required that the lieutenant be made presentable for propaganda purposes in the finest dress uniform on hand.

Prior to his departure, his prison mates offered up all the ribbons they had retained to decorate his uniform, and he showed up for his interview with a volume of service ribbons befitting a general.

In total, 17 Nisei would become POWs in Europe. Kanaya came out of the war with a Silver Star and Bronze Star, and he would acquire a second Bronze Star in the Korean War. Captain Kim also continued his Army career, serving in the Korean War as a lieutenant colonel.

Among the recollections of Biffontaine, S/Sgt. Kakuto Higuchi, 21 years old, remembered entering the small, rural village on October 16, 1944. He said that the nights were so dark within the Vosges Forest that men had to mark their sleeping areas, foxholes, and firing positions at night with toilet paper lest soldiers stumble into other soldiers’ positions.

Early one morning, Higuchi’s section of Company C of the 100th/442nd heard a noise of unknown source. It was nothing resembling a tracked vehicle, and no friendly tanks were in the immediate area. Whatever the noise, Higuchi’s group emptied full magazines in its direction.

After dawn, they investigated and found only a bullet-splintered wooden cart and a dead horse. The driver was nowhere in sight, and there was no evidence of injuries. The cart was a breakfast wagon, delivering that morning’s meal and five-gallon cans of milk to the Germans occupying Biffontaine. Higuchi’s group returned to their positions to enjoy an unexpected warm breakfast and fresh milk for a change.

After breakfast, the battalion made a rushed march to Biffontaine. The three companies—A, B, and C—lined up a plan of assault against the German-held village. But the surprise attack was spoiled when a Company C machine-gun team spotted a German command car enter the village and fired on it. That alerted the Germans, and the element of surprise evaporated.

Dodging MG-42 machine gun fire, Higuchi’s platoon reached a ditch with all men intact, and the platoon leader pointed out a white house across an exposed field, telling the unit to take it—and to expect “Jerry” to be inside.

The house was enclosed by an eight-foot-high steel fence. The six German soldiers that Higuchi and his colleagues found inside were all too willing to surrender. At first, they were corralled into a first-floor hallway, happily complying, and then shuttled upstairs.

From the upper floor, Higuchi saw a German at the far end of the house’s yard digging a foxhole. His back was turned to the house; he never knew he was being watched. In a collaborative team agreement, it was decided that the BAR man would have the “honor” of dispensing with the shoveling figure. Once that was settled, a second figure replaced him, meriting again the same “honor.”

Half an hour later the situation thickened when a Panzer IV rolled up to within 60 yards of the house. At first the tank swiveled its turret, trying to knock the steel fence apart for easier infantry access. That proved too time-consuming, so the panzer fired an 88-mm round into the house and rolled away.

Shortly thereafter, a German half-track replaced the tank and commenced firing at the house. The original hole became wider, growing to measure six feet by 10 feet. After that, the armored vehicle drove off.

A lull settled in within the house, which allowed Higuchi’s Company C group to watch Company B rout an equivalent number of Germans back into the trees.

During this lull, two unexpected visitors materialized. Two families had hidden themselves in the cellar throughout the day. Now two women came up to cook a dinner to be taken back downstairs.

Throughout that process, Higuchi held a position by the back door. Soon he heard footsteps outside as a German tried to creep up to the back door. Higuchi shot blindly through the door, the visitor retraced his steps, and the two women continued cooking their “dried beef … cabbage soup,” sharing a cup each with the GIs. When the women returned downstairs, the previously captured Germans went along and were secured there.

As the night wore on, Higuchi’s men were subjected to probing assaults from the neighboring house. It was not until morning that Higuchi realized that the neighbor’s house was the command post for the German battalion occupying the village. The probing and assaults were so persistent that Higuchi’s group had to start using German stick grenades, known as Stielhandgranate or “potato mashers,” to spare the use of their own grenades.

Their greatest shield against incoming ordnance were the heavy wooden shutters, which deflected incoming MG-42 bullets. The Germans kept yelling out in English the word “surrender,” but after a long impasse the yelling faded away. With the intensifying silence outside, stillness crept in throughout the house until one of the GIs remembered the captured Germans downstairs.

Higuchi was sent down below to check on them and the civilians and to establish a proper guarding of them. He found the families huddled in one corner and the Germans sitting in a line in the opposite corner. One barely spoke English.

Higuchi did the most appropriate thing a GI could do—he shared his cigarettes. One German repaid that act of kindness and offered Higuchi one of his own cigarettes that tasted like dried grass. Once the prisoners were turned in, the 442nd was given a five-day rest (which would only actually last three days).

Meanwhile, Sergeant Isuzu Sasaoka was atop a Sherman tank, part of a convoy delivering supplies to the 100th/442nd prior to their attack on Biffontaine. Sasaoka manned a machine gun, firing upon the attackers until the column was overwhelmed.

Those escaping the melee stated that Sasaoka was severely wounded and quite probably captured, but that was never officially confirmed. The only suggestion of his fate came from another POW claiming to have seen him in captivity. When the Russian Army liberated that camp, Sasaoka disappeared without a trace; it is speculated that this was directly due to his so-called liberators.

Rescuing the Lost Battalion

Beginning on October 25, 1944, the 100th/442nd RCT took part in their best-known action. Dahlquist’s 36th Division was fighting in the Vosges Mountains when 270 men of the 1st Battalion, 141st Regiment, found themselves surrounded by 6,000 Germans.

In the legendary saga of the 442nd and the “Lost Battalion,” the 1st Battalion men were stranded for two days on a ridge near St. Dié and were perilously low on food, water, and ammunition. Air-dropped supplies ended up in enemy hands. Dahlquist ordered the 442nd, which had just come off the line for a much-needed rest, to attempt a rescue of the surrounded battalion.

Marching four miles in darkness, up hills and through thick forests, the 442nd finally ran into the Germans surrounding the ridge. During 16 days of the most furious combat imaginable, the outnumbered Nisei soldiers proved to the Germans who the real “supermen” were.

Despite intense artillery barrages, sweeping machine-gun fire, fully manned entrenchments, and enemy snipers, the men of the 442nd—the 3rd and 100th Battalions—fought their way forward, taking heavy losses with each step.

One of the men, Sergeant Daniel Inouye, escaped death when a bullet struck him in the chest but was stopped by the lucky silver dollars he always carried in his breast pocket. In recognition of Inouye’s courage and leadership during the battle, he received a rare battlefield commission to second lieutenant. Inouye also received the Bronze Star Medal for his heroism during the battle.

On October 30, just when further advance seemed impossible, the Nisei soldiers steeled their courage and decided to “go for broke.” Yelling at the tops of their lungs, the men rushed uphill in what one historian described as a “banzai charge.” The German lines crumbled, and the enemy fled into the woods; the “lost battalion” was saved.

It came at a terrible cost, however. According to the Go for Broke National Education Center, “On November 8, when the 442nd was finally relieved, the dead and the wounded outnumbered the living. The 442nd ended up at less than half its usual strength. K Company, which started out with 186 men, had only 17 riflemen and part of a weapons platoon left. I Company started out with 185; at the end, there were only eight riflemen.” Recent research gives the 442nd casualties for the battle at 37 killed and over 400 wounded.

Decorations for valor were showered on the men of the 100th/442nd. Privates Barney Hajiro and George Sakato were both initially awarded the Distinguished Cross, while Tech 5 medic James Okubo received the Silver Star; in 2000, these awards were upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

On November 12, General Dahlquist ordered Lt. Col. Virgil Miller, commanding the 442nd, to have the entire regiment fall in to be recognized for their heroism. When only a small number of men appeared in formation, Dahlquist chewed out Miller for disobeying orders. “I told you to have the whole regiment,” he snarled.

“General, this is the regiment,” Miller replied. “The rest are either dead or in the hospital.”

Back to Italy

At the end of November, the Go for Broke boys relieved the 1st Special Service Force on the France-Italy border, where they rested and absorbed replacements until March 25, 1945, when they returned to Italy. There they were attached to the all-black 92nd Infantry Division and got back into the war. Heavy fighting in March and April along the Ligurian coastal sector brought more medals—and more casualties.

On the morning of April 21, 1945, 2nd Lt. Daniel Inouye was leading his platoon in an assault on a German-held ridge near the village of San Terenzo when he realized that he had lost his lucky, life-saving silver dollars. Three German machine guns opened fire. A bullet hit Inouye, but he continued to advance, throwing grenades and urging his men onward. Crawling close to the enemy emplacement, he threw two more grenades, killing the gunners. He then killed the crew of a second machine gun with his Thompson sub-machine gun.

Inouye was about to lob another grenade at a third machine-gun nest when a German shot him in the right elbow with a rifle grenade that exploded. He said, “I looked at my dangling arm and saw my grenade still clenched in a fist that suddenly didn’t belong to me anymore.”

With his left hand, Inouye pried his live grenade from his now-useless right hand and hurled it at the enemy soldier. Despite his wounds, he continued advancing and firing his submachine gun with his uninjured left arm but then was struck down by a bullet to his leg.

As a historian wrote, “When Inouye regained consciousness, he refused to be evacuated until he was sure his platoon had secured its objective. He continued to direct his men as they deployed in a defensive position in case of an enemy counterattack. Inouye and his men killed a total of 25 enemy soldiers and captured eight others in the successful attack.”

After being evacuated to a field hospital, doctors had to amputate his arm. He spent the next two years in army hospitals recuperating. He was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army in 1947 with the rank of captain. In 1963 he was elected a United States Senator from Hawaii, where he served until his death at age 88 in 2012. For his combat heroism, Inouye was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Bronze Star, Purple Heart with Cluster, and is the only member of Congress to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

These are just some of the stories of the 100th/442nd. In the course of the war, an estimated 18,000 Japanese-Americans rotated through the 100th/442nd and its support units. Among these men, nearly 15,500 military awards or decorations were given out, with a few thousand soldiers receiving awards or citations more than once. The 100th/442nd lost over 600 men killed and was awarded almost 9,500 Purple Hearts. The unit was awarded eight Presidential Unit Citations—five earned in one month.

While only one received the Medal of Honor during the war, another 21 were added upon a 1995 Congressional review of Distinguished Service Cross medals worthy of the nation’s highest military award but which may have been denied due to racism. While these men had diverse experiences during the war and came from different backgrounds, as clearly exemplified by the conflicts between the islanders and the “kotonks” during training, their undeniable devotion to their country was the unifying thread running through their service in Europe.

Remembering the words of young Stanley Izumigawa: “We should never forget these Japanese Americans who so valiantly fought in Europe for their country and their families.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments