By Daniel Murphy

Lieutenant Colonel William Washington of the Continental 3rd Light Dragoons stood in his stirrups and looked out over the open drover’s field stretching before him. British infantry were eagerly charging forward, their breath blowing clouds in the winter’s morning air as they trotted forward with bayonets fixed and ready. Washington watched eagerly as American Whigs raised their rifles in reply and slowly took aim. The British kept coming nonetheless, and then a series of volleys flashed out, obscuring Washington’s view as the Whigs opened fire.

When the smoke cleared, Washington could see that a good number of British infantrymen were down, but still more were on their feet. Worse yet, they were now coming even faster, knowing the Americans would never have time to reload before the British bayonets reached their line.

Lacking bayonets of their own, the American riflemen began to turn about and abandon their position. This was no surprise; it was all according to plan. The riflemen had orders to retire to the rear line and once there reform and reload. Instead, the surprise came from the British side of the field as the 17th Light Dragoons, which were the best cavalry the British had, suddenly appeared at the gallop.

British swords flashed overhead and horses bowled through the retreating riflemen. It was a light horseman’s dream—unloaded, fleeing infantry on firm ground—and the British troopers went at it full speed. In seconds they turned the riflemen’s orderly retreat into a panicked mass streaming for the rear. If the riflemen were routed, the American battle plan would be ruined, defeat would be swift and certain, and there was little Washington and his light dragoons could do about it.

At the start of the American Revolution there were few on the American side that thought raising a force of cavalry would be necessary. In contrast, the British understood the indispensable value of cavalry and sent their light dragoons early in the conflict where they quickly proved their worth by scouting, skirmishing, and screening the enemy as well as routing American infantry at White Plains and Indian Fields in 1776. The success of the British light horsemen prompted General George Washington to write the Continental Congress that he could not carry on the war without a cavalry force of his own.

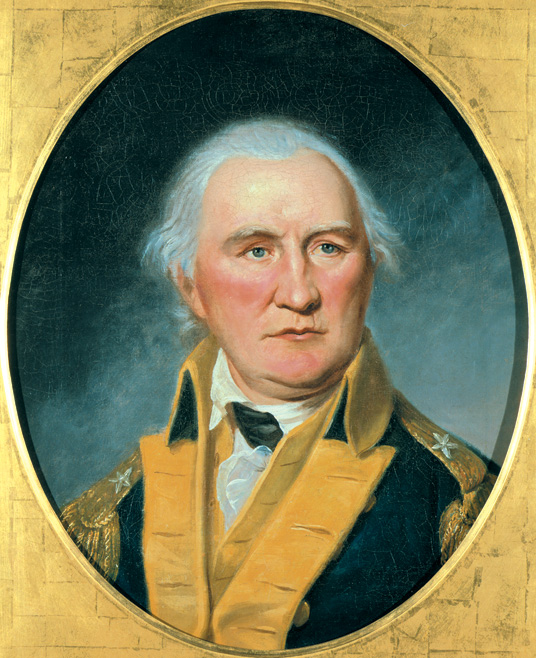

Congress complied and four regiments of Continental light dragoons were raised. William Washington, a distant cousin of George Washington, was awarded a major’s rank in the 4th Regiment. The younger William was born February 28, 1752, at Overwharton Parish in Stafford County, Virginia. Although born into the Virginia planter class, it was on a decidedly more middle-class level than his wealthy cousin George, who resided at the top rung of the elite tidewater planters. Though raised on the wrong side of the Rappahannock River, Washington nonetheless grew up in horse country and was riding soon after he could walk.

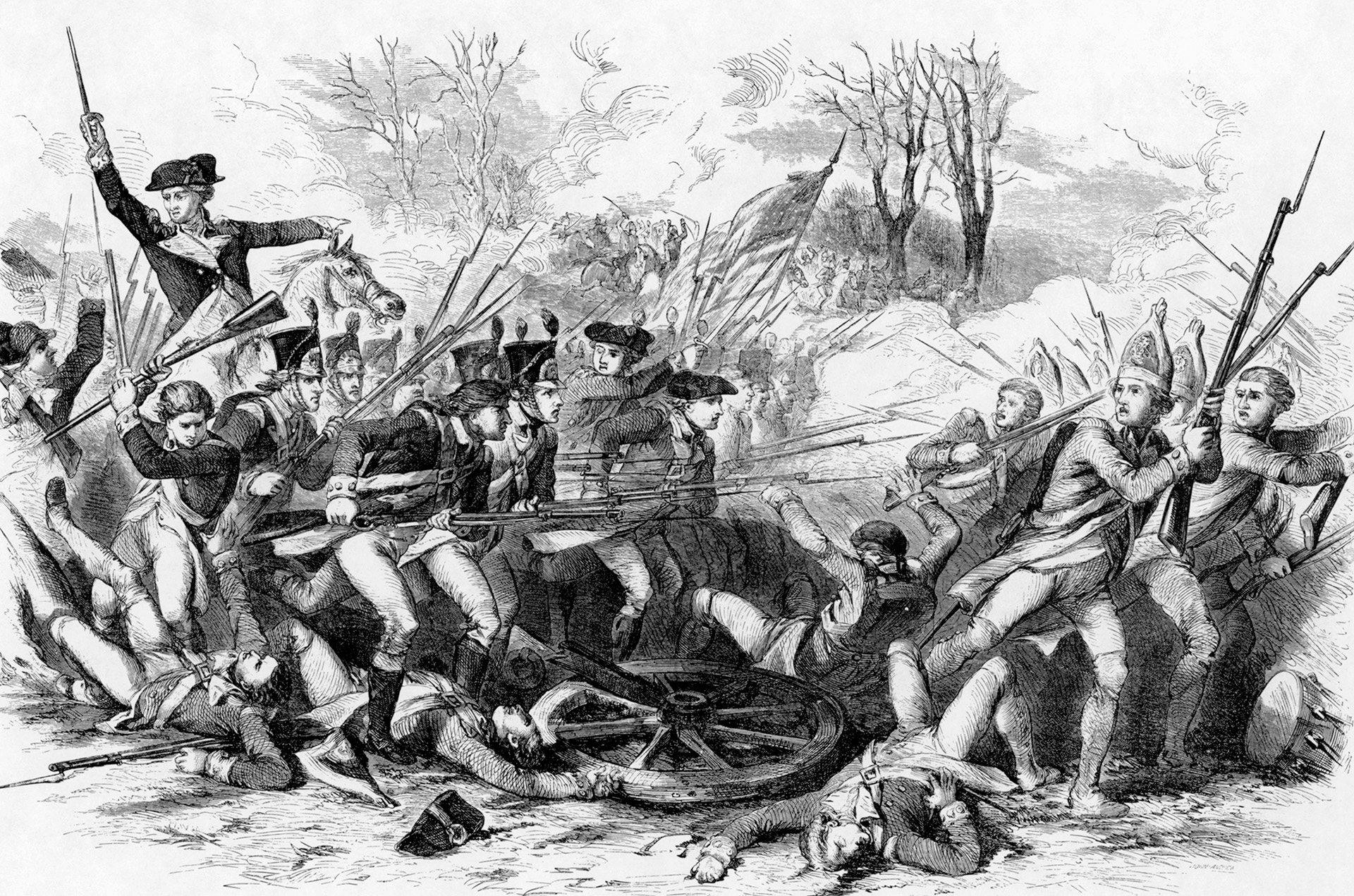

At the start of the war Washington joined the Virginia militia and was elected captain of his company. The company was absorbed into the Continental infantry and Washington saw action at the Battles of Harlem Heights and White Plains. At Trenton, Washington was selected to lead a forward vanguard of foot scouts. They were some of the first troops to cross the Delaware River. During the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776, a Hessian artillery battery was wreaking havoc in the tight streets. Without orders Washington led his men forward and captured the enemy battery in a brawling hand-to-hand battle for the guns. Wounded in the attack, Washington was led from the field, but his actions and instincts drew the attention of his elder cousin and commander.

While George Washington could be methodical and deliberate, William Washington was lively, outgoing, and quick to action; he was the sort who would place his hand on a friend’s shoulder when telling a funny story while walking through camp. William even formed friendships with noncommissioned officers, which was a crossing of social and military boundaries the elder George would have never sanctioned. Both men were brave before the enemy and magnetic leaders, with George always acting the proper Virginia gentleman and William affecting the rough and casual confidence of a country squire.

After the victory at Trenton, Washington was promoted to major, assigned to the light dragoons, and honed his new craft in the campaigns of Brandywine and Germantown in 1777 and Monmouth Courthouse in 1778. Like all light dragoons, Washington was also engaged in the day-to-day scouts, skirmishes, and screening actions of frontline cavalry where commanders survived on grit and instinct. Known as the petit guerre, or little war, the following account illustrates a skirmish fought between the lines by opposing light horsemen.

“Polasky with a body of his troops attacked a body of the enemy’s light horse,” wrote Colonel Samuel Hay. “He sets no store by carbines or pistols, but rushes on with swords…. They had severe cutting and slashing; the enemy had five killed and two taken prisoner besides a number wounded.”

A second American officer echoed the same sword-based tactics: “Firearms are seldom of any great utility to cavalry during an enemy engagement,” wrote Captain Epapharus Hoyt. “Indeed there is little hope of success from any who begin their attack with the fire of carbines or pistols…. It is by the right use of the sword they are to expect victory.”

Why was this? Firearms certainly had a far greater range than a three-foot sword. A quick look at the carbines and pistols being used supplies part of the answer. They were smoothbore, muzzle-loading weapons and loading them from the back of a horse was a laborious process at best. Smoothbore pistols were also woefully inaccurate beyond 30 paces and the range was even worse from the back of an excited horse in a battle line. Longer length carbines increased the range but required both hands to aim and fire, which simply was not practical when engaging an enemy at close quarters. Opponents countered by drawing swords, clapping spurs, and charging through the weak gunfire to cut the mounted musketeers to the ground.

But it was not simply the sword that governed a light horseman’s tactics or delivered the shock of the charge; the primary weapon of any light dragoon was his mount. With trooper and kit aboard, a light dragoon mount became a 1,000-pound missile that closed at more than 30 miles per hour to punch saddle-wide gaps through enemy ranks of infantry and cavalry. These gaps destroyed enemy discipline, and when light dragoons were marshaled together and led against the enemy at speed they could collapse entire flanks and create a rout. Once the rout was on, the sword was at its most effective. But it was the horses bowling through the enemy that broke the opposition; the attending sword blows were secondary.

After serving nearly two years on the front with the 4th Light Dragoons, Washington was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given his own regiment, the 3rd Light Dragoons. Once in command, Washington requested the 3rd be sent south where the British were now seeking a new strategy to bring the American rebellion to heel. After years of fighting in the northern colonies, the British had failed to land a killing blow. But on December 29, 1778, the British captured the port of Savannah, Georgia. The British noose was now in place to choke off the lucrative rice trade that helped fuel the foreign support floating the American cause. If the British course continued, Charleston, South Carolina, would fall along with the rest of the profitable rice crops. North Carolina and Virginia would then be next in line with their bankable tobacco fields. The British were determined to end the American exports and chop the Revolution off at its knees.

Washington arrived in South Carolina just as the British war machine was launching an overland assault on Charleston. He quickly joined the deadly skirmishing taking place and soon won a galloping victory against a rising star in the British cavalry, Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, when Washington pinned Tarleton’s troopers at Rantowles Bridge on March 27, 1780, and cut a number from the saddle. Tarleton later turned the tables and caught Washington’s 3rd Light Dragoons on May 6 at Lenud’s Ferry on the Santee River. Washington’s men were returning from a foraging raid when ordered to dismount and unsaddle their horses with the broad Santee at their backs. Washington protested the order to dismount and unsaddle, but he was overruled by Lt. Col. Anthony White of the 1st Light Dragoons. Washington’s men had no sooner complied with White’s order than Tarleton arrived at the gallop and cut through the dismounted Americans. Tarleton’s victory was total. Washington’s men suffered heavy casualties and all but 12 of his horses were seized. Washington and a few others escaped by swimming the Santee, a 300-yard stretch of snake-infested water, as Tarleton’s men galloped down the bank snapping pot shots at the swimming Continentals.

Charleston fell on May 12 and with it went 5,000 Patriots and their arms. It was the greatest American defeat during the war, and the British now held the most lucrative port in North America. Washington and the few surviving Continentals retreated to North Carolina where they were out of range of a British attack. The 3rd Light Dragoons were in tatters and Washington, no doubt itching for a chance to avenge his fallen comrades, could only dream of a day when he could exact his retribution against Tarleton.

Less than six months later Washington was back at the front with his refurbished command. Funding for remounts had been almost impossible to find, and it was a cobbled-together force he now led with only three undermanned troops of the 3rd Light Dragoons and an additional single troop appropriated from the 1st Light Dragoons. Returns show they were properly uniformed but lacked carbines of any kind and were short on pistols. But every man in the saddle was fitted with a proper horseman’s sword and well drilled in its use. Upon reaching the lines, Washington and his men were assigned to the command of Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan.

Daniel Morgan was a frontier legend. He was a former teamster and Indian fighter who led a corps of riflemen with great success in the Saratoga campaign of 1777. Morgan was rough edged and gregarious by nature and a soldier’s kind of soldier. He surrounded himself with men who would fight when put to it, and he did not tolerate anyone unable to toe the line. Morgan was also the sort that would not stand for the jaunty, preening sort of cavalry officer many were reputed to be. But Washington was a former infantry officer himself, comfortable with thinking on his own feet and known for leading his men from the front. Morgan found a like individual in the young Washington, and unlike most Continental officers who treated the militia like unwashed step children, both Washington and Morgan would overlook tiny details of military discipline if a man was motivated, loyal to the cause, and willing to fight. Both officers also understood the potential value and experience militias could share about local terrain and environment, and the expertise they could offer from previous fights with the enemy.

This rare trait would soon serve the officers well as Morgan was ordered to lead a small, fast-moving strike force, or flying army, of hand-picked troops into the Carolina backcountry. Morgan had orders to threaten the flank of the British troops building under Maj. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis and to stall any plans the British might have for moving north into North Carolina and Virginia. Once in the backcountry, Morgan’s flying army would be dependent on local frontier Whigs for provisions, and he would also need to draw troops from backcountry militias if he was to have any hope of offering battle against the British.

Morgan’s flying army moved west in December with Washington’s 3rd Light Dragoons leading the advance. Also in Morgan’s ranks was a mix of veteran Continental infantry from Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia under Lt. Col. John Howard. Despite Morgan’s frontier reputation, he soon found the backcountry Whigs were not streaming in to join his ranks in the numbers he had hoped. This was in part due to a force of 400 Georgia Horse Rangers under British Colonel Thomas Waters, who had been raiding and razing the frontier farms of backcountry patriots in Georgia and South Carolina. When word arrived that Water’s notorious horse rangers were pillaging south of Morgan’s position, he turned Washington loose.

Washington rode fast and hit hard. He covered 50 miles in a day and a half, leading his light dragoons along with a picked force of backcountry militia dragoons to catch Waters’ Rangers at a frontier trading post called Hammond’s Store on December 27.

“Colonel Washington and his dragoons gave a shout, drew swords, and charged down the hill like madmen,” wrote Private Thomas Young of McCall’s Mounted Militia, which fought alongside Washington’s men.

Washington led his men in at the gallop and cut the British Tories down in heaps. The casualties were decidedly one sided, and it is quite likely that Washington considered Waters’ men to be little more than outlaws. Certainly the Tories’ reputation as plunderers and barnburners did them little favor with the backcountry militia accompanying Washington. All told 160 Tories were killed or wounded and 40 captured. Waters and the remainder took to the woods. The threatening presence of the Georgia Horse Rangers had been removed, and Morgan soon saw a marked increase in the numbers of militia coming into his camp.

The British high command quickly recognized this new development and sent their star performer, Banastre Tarleton, to deal with it.

Since landing outside Charleston, Tarleton had gained prominence through a series of bold, headlong charges and won victories at Monk’s Corner, Lenud’s Ferry, Fishing Creek, and Waxhaws, including a brilliant flanking charge at the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780. Tarleton was bold, cunning, and capable. He was everything a light horseman was supposed to be. He was also ruthless, headstrong, and deceitful, and happy to brag on his laurels and strut about as the beau sabreur of all British cavalry. However, Tarleton had recently suffered a costly reversal on November 20 from backcountry Whigs at Blackstock’s Farm. For the first time Tarleton’s headlong charges had been answered with disciplined volleys that stopped him cold and forced him to retire from the field. Undaunted, Tarleton returned the following day after the Whigs left the field and claimed a victory. Tarleton then falsely reported the outcome to his superiors. When Cornwallis picked Tarleton to chase down Morgan’s flying army, Tarleton no doubt jumped at the opportunity.

Cornwallis gave Tarleton his own flying corps of horse, foot, and artillery. For cavalry Tarleton had 250 troopers from his own British Legion dragoons and another outstanding troop of British regulars, the 17th Light Dragoons. On foot Tarleton had an excellent mixed force of highlanders, fusiliers, and light infantry, as well as his own British Legion infantry. He was also trusted with a pair of mobile three-pounder cannons called grasshoppers, containing two gun crews and mounted drivers. All together this force consisted of more than 1,200 men. It was a fast-moving corps, a flying army perfectly suited to the mission and the best troops Cornwallis had available. With this command in hand there was little British doubt Tarleton could annihilate any American force he caught up with in the backcountry.

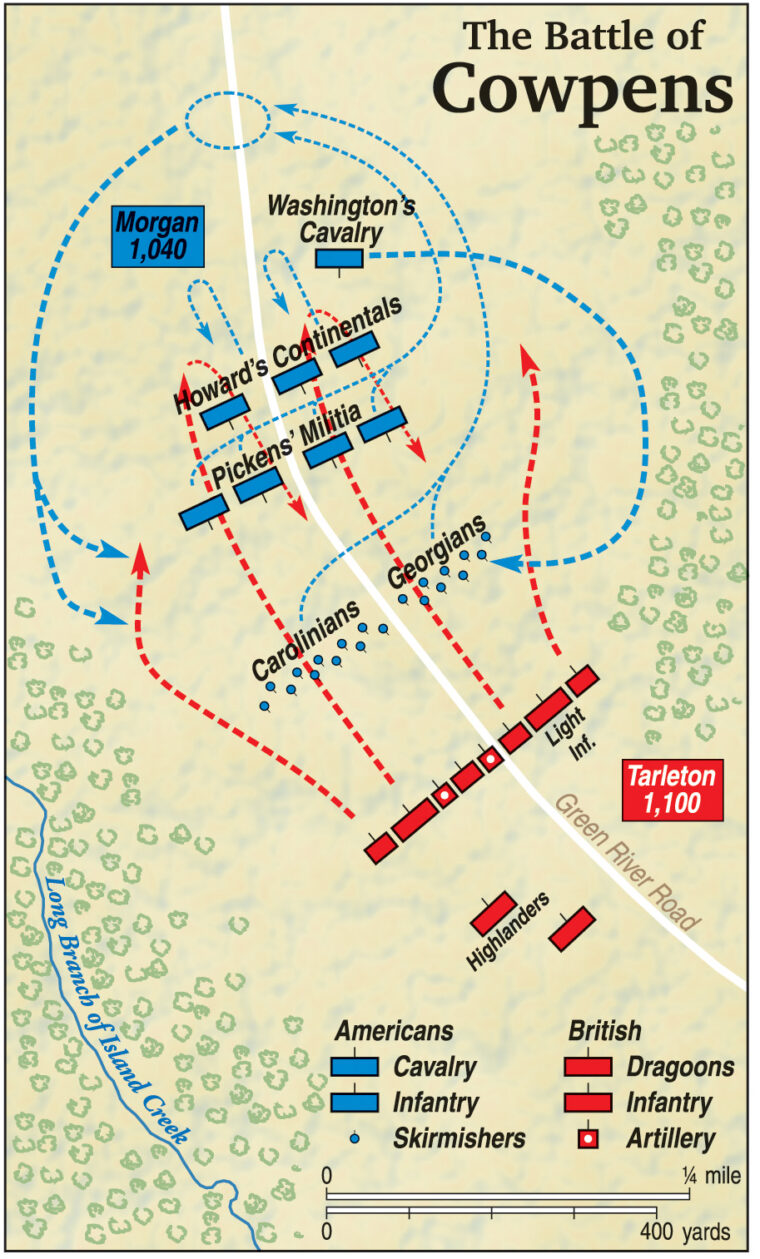

In the meantime, Morgan was collecting one of the largest forces of American militia ever seen in the backcountry. Whig riflemen were now riding in from the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia. Together with his Continentals, Morgan now had a total force of approximately 2,000 men, and he chose a popular drover’s field, known as the Cowpens, to offer battle. The ground at the Cowpens was well suited for a defensive fight and centered around a large open field with little underbrush, few trees, and the ground sloped rearward in a series of low ridges that would help hide Morgan’s men. Natural springs and thick vegetation on either side offered protection from wide flanking attacks of enemy horsemen.

Morgan received word that Tarleton was moving against him with a powerful force of combined arms, and he began polling the veterans in his camp who had fought Tarleton before—backcountry men like Majors James McCall and Benjamin Jolly and Continentals like Howard and Washington. After talking with everyone he could find, Morgan formed a plan that combined both terrain and resources. Nearly all the veterans predicted Tarleton would want to attack straight away. For this reason, Morgan felt his best chance for success would be a defense of multiple lines and weaponry. He placed his slow-loading militia riflemen in two forward lines at the head of the field, and his quicker loading Continental muskets in a third line in the rear on lower sloping ground where they would be harder to identify. Washington’s light horsemen would hold in reserve and guard the flanks from mounted attacks.

As the British attacked, the forward rifles would first engage the enemy and aim for the epaulets of British sergeants and officers to cripple the British command structure at its most fundamental level. The riflemen would then fall back and join the third line. This way the militia would not have to stand up against the British bayonets; instead, they could fire their rifles and make an orderly retreat. The third line of Continentals would then blast quick, close-range musket volleys of buck and ball at the disordered British ranks while the militia reformed and came back on the flanks to take the remaining British in an enfilading fire. Brig. Gen. Andrew Pickens would command the forward militia riflemen while Howard would command the third line of Continentals. Washington would command the cavalry and stand ready to exploit or defend any breaks in the line as he saw fit.

One major risk in Morgan’s plan was that his militia riflemen were excellent skirmishers, but they were not regular troops disciplined to stand in pitched combat. Because they lacked bayonets, they might not reform and reenter the fight according to plan. Without their support, Howard’s third line of Continentals would potentially be outnumbered and exposed to Tarleton’s greater force of cavalry, which might cut them to pieces. Nearly all of the militia riflemen had arrived mounted and would have their horses tied in the rear. It was because they had a ready escape mechanism in place that they were willing to risk battle in the first place. Morgan knew he would have to do all he could to keep the militia from fleeing, so the night before the battle he worked his way through the militia camp, joking and cajoling with the men. Fire and reform in the rear to win, he told them repeatedly.

That same night found Washington squaring away his 80 light dragoons and their horses. He was also busy attending to the mounted militia troops of McCall and Jolly.

McCall was a tough-minded frontier dragoon and former Indian fighter who had taken part in a number of engagements against the British, including Washington’s recent victory at Hammond’s Store, as well as Tarleton’s defeat at Blackstock’s Farm. McCall’s troop of backcountry dragoons was also one of the few militia units armed with broadswords and therefore able to fight from the saddle as true cavalry and not just mounted infantry. Jolly was another flinty backcountry veteran who, like McCall, had made a positive impression on Washington. Jolly was selected to form and command an additional troop of mounted volunteers from men who rode at Hammond’s Store, and Washington issued the new troop 40 swords stored in the 3rd Light Dragoon’s baggage. Between McCall and Jolly there were roughly 90 state dragoons, enough to form a separate squadron of militia dragoons capable of independent action.

First contact with the enemy was made well before dawn by a vedette sent from Washington’s 3rd Light Dragoons. Commanded by Sergeant Lawrence Everhart, the vedette stumbled into range of the British van in the dark predawn woods and Everhart had his horse shot out from under him. Dragged before Tarleton, Everhart was asked if Morgan would stand and fight. Everhart hedged the numbers and slyly replied they would if able to keep but a few men together. Tarleton then boasted that if they did it would be another defeat like the American disaster at Camden. Everhart brashly answered back that he hoped to God it would be another Tarleton defeat, referring to the recent action at Blackstock’s Farm. Just what Tarleton said in reply is lost to history, but he ordered a British surgeon to dress Everhart’s wounds.

The rest of Everhart’s vedette rode back to the American lines and warned of the coming British assault. Just as dawn broke the horizon, the sound of rifle fire split the cold morning air, and a party of probing British dragoons was driven back by a rifle volley. Tarleton then edged forward in the early morning light, briefly studied Morgan’s lines and, as predicted, decided to attack immediately.

The British dropped packs and quickly readied for action. Tarleton directed the British Light Infantry battalion to the British right, his legion infantry to the center, and the 7th Fusiliers on the British left. Lieutenant Henry Nettles’ troop of 17th Light Dragoons was formed in rear of his right flank behind the light infantry, and on the British left Tarleton placed a troop of British Legion Dragoons under Captain David Ogilvie. Tarleton’s two artillery pieces came forward to support the infantry’s advance, and the 71st Highlanders were posted as a reserve in the rear along with the remaining 200 British Legion dragoons.

The British infantry gave a shout and moved forward at the trot, soon coming in range of Pickens’ militia riflemen. The backcountry riflemen opened a rolling fire and the lethal volleys cut through the British ranks in a whistling rain of buzzing and spinning rifle balls. Stunned, the British dressed their lines, dragged their wounded clear, and kept coming. Years of fighting in America had taught the British to absorb the first volley and rush ahead with the bayonet before the slow-loading rifles could manage a second fire. Only one rifle battalion managed a second volley as the British closed with their bayonets, and then Pickens ordered his remaining battalions to fall back as planned.

When Tarleton saw the riflemen withdrawing, he waved the 17th Light Dragoons forward to charge the retreating militia and create a rout. Militia rifleman James Collins remembered thinking, “My hide is in the loft,” as the British Light Dragoons slammed into the retreating Americans and quickly turned an orderly withdrawal into a panicked flight. The impending rout would annihilate Morgan’s battle plan.

Watching this from behind Howard’s third line was Washington, no doubt standing in his stirrups and marking every step of the British attack. The militia was fanning out before the pursuing British horses and with Howard’s line still in place Washington had no line of attack. Washington also knew that could quickly change as the enemy light dragoons passed Howard’s line and spread out in their pursuit of the fleeing riflemen. By then past Howard’s line, the 17th Light Dragoons’ left flank was suddenly hanging wide open, and every Continental veteran of Lenud’s Ferry realized revenge was but a short charge away.

Trumpets sounded, spurs swept back, and Washington led his Continentals forward with swords aloft, crushing the 17th Light Dragoons’ open flank and cleaving the British rankers from their saddles.

“Col. Washington’s cavalry was among them, like a whirlwind, and the poor fellows began to keel from their horses, without being able to remount,” wrote South Carolina militiaman James Collins. “The shock was so sudden and violent, they could not stand it, and immediately betook themselves to flight.”

Washington’s troopers rallied and rolled on, pursuing the 17th Light Dragoons, cutting them down until they overtook the British artillery drivers posted on the British right flank. The British drivers refused to yield and the Continentals quickly shot down the artillery horses with their pistols, severely retarding the British gunners’ ability to move their pieces. Washington then rallied his men and brought them back behind Howard’s line, rejoining McCall’s and Jolly’s waiting militia squadron that Washington had left in reserve to cover his attack. Washington simply had not needed to commit his entire command to attack the 17th Light Dragoons’ scattered troop of British cavalry. Now free of threat, the backcountry militia riflemen began to rally under Pickens’ direction, and Morgan’s battle plan was again intact and functioning as planned.

Meanwhile, the infantry fight heated up before Howard’s line of Continentals. Advancing in the wake of Pickens’ fleeing riflemen, the British infantry now pressed forward and suddenly came under a crisp fire from Howard’s Continentals. As the two sides began to trade standing volleys, Tarleton decided to try and turn the opposite American flank and sent word for the 71st Highlanders to move forward and flank the right of Howard’s line.

Leading the Highlanders’ attack was a single troop of British Legion Dragoons. They spurred forward and cut through a company of riflemen posted on Howard’s right flank to guard his line from attack. The British Legion’s attack scattered the riflemen and the legion dragoons charged after them, in turn opening an avenue of attack for the 71st Highlanders, who swung in on Howard’s open flank.

Seeing this new break in the line, Washington sent the militia squadron under McCall and Jolly to attack the British dragoons while Washington held his own Continental Light Dragoons in reserve. The two companies of mounted militia rolled forward and struck the British dragoons at a gallop. They cut their way through the British ranks and, showing a discipline worthy of the finest veterans, McCall and Jolly wheeled their men about and rode through the British ranks a second time to drive the broken British Legion Dragoons from that portion of the field.

Meanwhile, a fresh disaster was in the making as the Highlanders swept forward against Howard’s open right flank. A mix up of orders occurred when the 1st Maryland tried to refuse its flank, and some of the Marylanders suddenly began marching to the rear. Smelling blood, the Highlanders broke forward in ragged pursuit. Morgan was furious and came galloping toward Howard to loudly inquire what was going on. Howard assured Morgan that his men were not beaten and just needed to fall back and redress. Morgan then directed Howard to reform in front of a small rise where Washington was fortunately still holding his Continental Light Dragoons in reserve.

The crux of the battle was now approaching. Washington watched the ragged pursuit of the Highlanders running forward in clumps of threes and fours, which in turn was creating disorder across the entire British line. Seeing this, Washington realized an opportunity was in the making and sent a courier galloping for Howard with the following message: “They’re coming on like a mob, give them one fire and I’ll charge them.”

The Highlanders continued to clamor after Howard’s men, closing to within 30 yards before Howard ordered his line to suddenly turn about and fire. A solid sheet of smoke and fire blasted out point blank at the Highlanders; when the smoke cleared half the Scots were on the ground.

Howard called for a bayonet charge and Washington’s trumpets split the air. Swords scraped free and Washington led his dragoons around Howard’s left to pitch into the right flank of the British infantry. The militia squadron was just rallying from its charge on Ogilvie’s dragoons as Washington was rolling forward.

“At this moment the bugle sounded,” wrote Young. “We, about half formed and making a sort of circuit at full speed, came up in rear of the British line, shouting and charging like madmen.”

Washington’s light dragoons struck the British ranks at a gallop, bowling their mounts into the flanks of the light and legion infantry and driving them back on the 7th Fusiliers, a rippling effect as the fleeing British troops piled roughly into their fellow soldiers and masked their fire. As Washington’s dragoons spurred and hewed their way through the enemy right, Howard’s men swept the Highlanders back on the British left. McCall and Jolly’s militia squadron now struck the enemy as well and Pickens’ rallied riflemen followed suit and swept in to open an enfilading fire on targets of opportunity. Morgan’s battle plan was now performing on a higher plane than the old wagoner had ever imagined.

Tarleton sat dumfounded as he watched his broken and fleeing infantry from across the field. In the span of mere minutes the fight had gone from rolling British victory to running British defeat. Tarleton turned to his reserve of 200 British Legion Dragoons. They had seen no fighting so far and with a spirited charge could perhaps turn the tide. However, the veterans of Monck’s Corner, Fishing Creek, and Lenud’s Ferry wanted no part of the hard fight and instead turned about and left their fellow British infantrymen to fend for themselves.

But the game Tarleton was not done. He grabbed a handful of mounted officers, couriers, and the remaining survivors of the earlier 17th and British Legion Dragoon charges and galloped forward with some 40 men in a desperate attempt to stem the tide, or at least gain some honor by rescuing his two guns stranded by Washington’s earlier attack.

Washington and his men were still focused on the British infantry, and Tarleton’s attack first took them by surprise, but the Continentals quickly rallied and repulsed Tarleton’s makeshift attack in a flurry of darting horses and ringing sword cuts. Outnumbered and outflanked, Tarleton’s men retreated without ever reaching the guns. Tarleton now realized the jig was up and turned his back on the field.

By this point most Continental officers were busy taking prisoners, but Washington was instead watching three British officers lagging behind Tarleton’s makeshift force. Two of them were officers of the British 17th Light Dragoons, but the third officer must have struck a chord with Washington as he clapped spurs to his mount and took out after this trio of enemy officers at a gallop. He outdistanced his fellow 3rd Light Dragoons and came on with the shout, “Where is now the boasting Tarleton?”

On this day British chivalry was decidedly lacking as not one but all three British officers turned about and made for the lone Washington. Rashly or not, Washington had made the challenge and it was now too late to turn back as he spurred straight on and closed with the three enemy officers in a swirling exchange of sword blows.

Luckily for Washington, help was on the way. Sgt. Maj. Mathew Perry of the 3rd Light Dragoons galloped into the ongoing melee and slashed a lieutenant of the British 17th Light Dragoons across the arm to knock him out of the fight. Seconds later a pistol cracked and the second officer of the 17th Light Dragoons reeled in the saddle and peeled off, mortally wounded from a snap shot fired from Washington’s waiter, a young steward too small to wield a sword. Meanwhile, Washington had closed with the third British officer and traded blows. “Washington made a hack at [Tarleton] … and glanced his head with his sword,” wrote James Kelley of the 3rd Light Dragoons.

This third officer made a lunge that Washington parried and broke the enemy officer’s sword in the process. The officer then wheeled out of range, drew a pistol, and shot Washington’s horse before galloping off the field.

“The one in the center who it is believed was Tarleton himself made a lunge which Washington parried [and] perhaps broke his sword,” wrote Howard. “The third then wheeled off and retreated ten or twelve paces when he again wheeled about [and] fired his pistol which wounded Washington’s horse.”

Most historians have thought that it was Washington’s sword that was broken in this duel, but the subject of the key sentence in Howard’s firsthand account is clearly Washington’s adversary, and as it follows, the possessor of the broken sword. A thrust blade always suffered the hazard of being parried and bound in an opponent’s webbing or saddlery, where the caught blade could easily twist, bind, and break as the two parties whirled about. Once the enemy officer’s sword was broken he wheeled out of range, drew a pistol, and took a shot at Washington. If it were Washington’s blade that was broken, the enemy officer would have closed in and dealt Washington a heavy blow.

Less conclusive is whether this third officer was actually Tarleton. Washington left no written account of his actions during the war; however, Tarleton was one of the first officers to publish a memoir. Tarleton went into much detail of the Battle of Cowpens but curiously, of this particular phase, only claimed that he and his collected force of 40 men charged and drove off Washington’s light dragoons, a dubious claim that was later refuted by officers on both sides.

Regardless of who this third officer actually was, he quickly scampered from the field in an effort to join the rest of the fleeing British dragoons. Washington switched horses, gathered his men, and gave chase to Tarleton and his dragoons but was purposely misdirected by a woman whose husband had been forcibly impressed by Tarleton as a guide and held hostage on pain of death. Washington was directed down the wrong road and failed to catch his quarry.

In any case, the Battle of the Cowpens was over and the Americans had scored a resounding victory. To this day, the battle is considered the most complete tactical success of American forces during the war. It was also one of the quickest, as it unfolded in 20 minutes or less in scenario models. All cavalry actions are quick by nature, and the fluid series of countercharges directed by Washington negated Tarleton’s superiority in cavalry, stabilized the American infantry, and rescued Morgan’s battle plan.

Washington repeatedly acted on his own instincts, covered both sides of the American line, and still managed to deliver a crushing blow at the end that rolled up the right flank of the British infantry. It was the best battlefield performance of any cavalry leader during the war. Aside from Tarleton’s fleeing dragoons, the entire British flying army was captured or killed and Washington was justly awarded a Congressional medal for his role in the fight. The Battle of Cowpens was a milestone victory of American arms, and the loss of Cornwallis’ flying army hampered British efforts for months to come.

After Cowpens, Washington’s light dragoons continued to wreak havoc against the British throughout 1781, fighting at Weitzel’s Mill, Guilford Courthouse, Hobkirk’s Hill, and Eutaw Springs. Washington’s command became the hardest hitting force of light horsemen in Continental service. But Washington’s aggressive instincts and casual nature, traits that served him so well alongside Morgan, did not always sit well with the more formal officers in Continental service. Issues soon arose with supply officers in the quartermaster corps and fellow dragoon officer Lt. Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee.

The campaign for the Carolinas climaxed at the Battle of Eutaw Springs on September 8, 1781. Washington was captured there while leading a charge against British infantry. While prisoner he was granted permission to marry Jane Riley Elliot, a fetching young rice heiress from South Carolina. After the war, Washington stayed in South Carolina, where he served in the state legislature, became a leading figure in Charleston society, and built a thriving stable of thoroughbred racehorses. He died on his plantation at the age of 58.

The finest compliments often come from one’s enemies, and long after the war Washington’s chief adversary, Cornwallis, penned the following words regarding his former nemesis: “There could be no more formidable antagonist in a charge, at the head of cavalry, than Colonel William Washington.” For those who had fought alongside Washington, and for those of that generation and future ones who were told of his feats, it was a just and fitting tribute.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments