By Tim Miller

On Monday evening, April 27, 1942, Kathleen Stainer and her family readied themselves for sleep in the English countryside. Having walked about a half mile away from their home in the city of Bath, they found a spot just off the road where they could finally throw down their bedding.

The distance seemed safe enough, but before they fell asleep—and this assuming they slept at all—they made sure to cover their faces. No one knew for sure whether the Luftwaffe was returning that night, but Kathleen and many others had already heard the stories of German machine gunners in low-flying bombers shooting at anything that stood out in the dark, whether a poorly blacked-out window or a recognizably human form.

Over the past two nights, fights had broken out over whether or not it was safe to even light a cigarette. Who knows how their upturned faces may have looked against the dark ground? Others, scattered throughout the countryside around Bath—whether out in the open or down in nearby mines—no doubt asked themselves the same questions. In retaliation for the RAF bombings of Lübeck and Cologne, the Germans had attacked Bath three times in the previous two nights.

The city had been a vacation spot as far back as the Romans, who had taken an already pagan association with the local hot springs to build a spa complex and religious center that still stands today. By 1942, the Roman remains had themselves become surrounded by more than 2,000 years of history—from its medieval abbey to its famous Georgian architecture, which culminated in the great Royal Crescent, built in the late 18th century.

Bath was also supposed to be relatively safe from German attack, having very little by way of an industrial center. Awful as it was, it at least made some strategic sense that places like Manchester or London or Coventry were bombed. And indeed, during the Blitz many locals in Bath—and many in London who could not afford it—resented the more well off, who had fled the capital for places like Bath to wait out the attacks there. Early in the war, more than 4,000 civil servants had been relocated to Bath from London for their own safety, again earning the ire of almost everyone else.

Little could Bath have guessed, though, that it would be targeted precisely for its cultural and historical—rather than military—significance. Alongside other ancient cities like Exeter, Canterbury, Norwich, and York, Bath would take its place in the history of the war as one of the “Cathedral Cities” sought out by the Luftwaffe. These were the “Baedeker Raids,” named after the red-covered travel guides found all over Europe during the first half of the 20th century.

After the raids began, German Baron Gustav Braun von Stumm, Deputy Head of Information and the Press Division of the Foreign Office, remarked to reporters, “Now the Luftwaffe will go for every building which is marked with three stars in Baedeker.” Ever since the end of the war, similar remarks have also been attributed to Hitler, though there is no evidence he ever said them.

Much to the consternation of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, von Stumm had not only told the truth, but did so in a way that Goebbels must have known would stick. Until this point, the bombing of civilians had always been explained away by stating the military objective of the attack, however slight and disingenuous it might be. No such remark, for instance, was ever made publicly about the German bombings of Warsaw and Rotterdam, which in propaganda terms became legitimate targets simply by refusing to surrender.

Yet von Stumm’s accidental slip into the truth revealed a reality that had been coming for some time: that the pulverizing of civilian morale was now a legitimate means of seeking victory. If the men and women far from the front lines could be made to feel that the front lines had come to them, they might become so fed up with the government that a continuation of hostilities would be impossible.

This conclusion was also the result of necessity rather than ruthlessness, as the inferior technology used in early bombing raids shows; initially, many British bombers sent on daylight raids were unable to find their target city, let alone attack the industrial centers with any precision. As late as the Baedeker Raids, some German planes never found Exeter. Even the bombing of legitimate targets resulted in unintended civilian deaths, as the RAF bombing only a month before Bath showed, killing more than 300 French civilians in their raid on a Renault factory outside Paris, now being used by the Germans.

But, by and large, the Baedeker Raids were something different, as were the British attacks on Lübeck and Cologne that prompted them. In short, accidental civilian deaths due to technological limitations had transformed, in response to a heightening of atrocity and escalation of violence elsewhere in the war, into the need for better technology and the intentional killing of civilians.

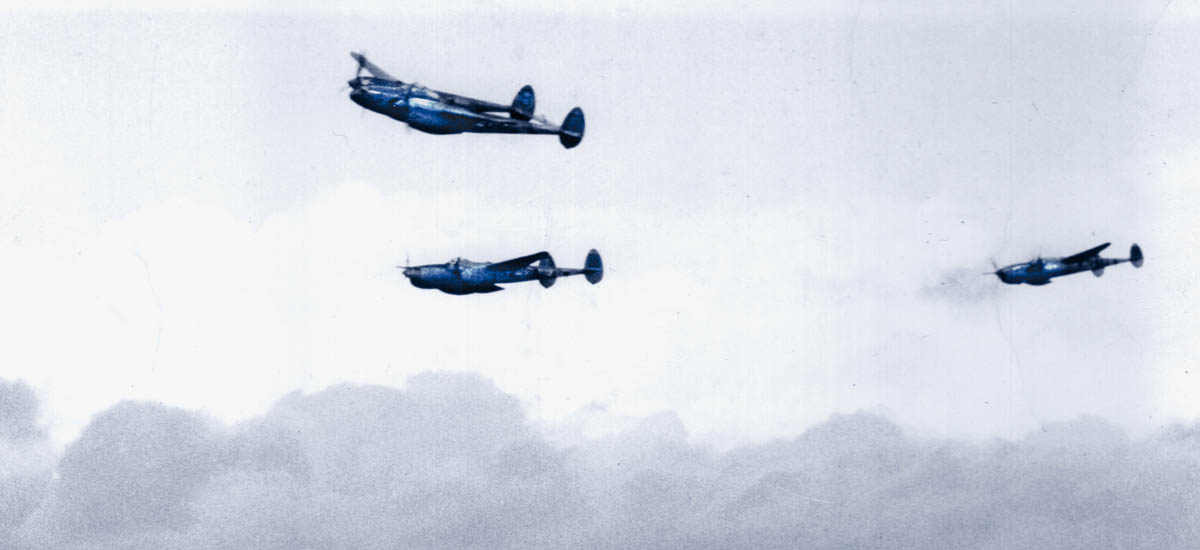

Alongside Britain’s decoding of Germany’s Enigma machines, by 1942 technological advances on both sides—in everything from better aircraft (and signaling devices to guide them to the target) as well as better radio communications and early radar (but also a greater ability to intercept or jam all of these)—bombing missions could be undertaken with even greater skill than ever before. Should the target city be properly protected, it could also better defend itself—but Bath was not one of these cities, lacking entirely in either searchlights or antiaircraft guns, facts the Germans must well have known.

Nowhere is the changing mindset on the necessity of civilian bombing better illustrated than in two remarks made by President Franklin Roosevelt, separated by a few years: on September 1, 1939, he could speak of the “ruthless bombing from the air of civilians in unfortified centers of population … which has resulted in the maiming and in the death of thousands of defenseless men, women, and children, has sickened the hearts of every civilized man and woman, and has profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity.”

Yet he came to later admit, “We must face the fact that modern warfare as conducted in the Nazi manner is a dirty business. We don’t like it—we didn’t want to get in it—but we are in it and we’re going to fight it with everything we’ve got.”

While the British did not slip up like Baron von Stumm, their tactics by this time were clear. What von Stumm had chosen to state in public, the British only made clear in their private directives. One, issued in February 1942, said, “The primary object of your operations should now be focused on the morale of the enemy civil population, and in particular on the industrial workers.”

In choosing to bomb Lübeck on March 28-29, Bomber Command had indeed chosen a city whose industries were important to the German war effort, since its position on the Baltic allowed it to resupply the German Army in the east, as well as receive iron ore from Sweden.

But more important even than these was Lübeck’s city center. For, while it was far from its industrial works, it was also, in the words of the new head of Bomber Command, Arthur Harris, “built more like a fire-lighter than a human habitation.”

The area, essentially an island linked to the surrounding area by bridges, was packed with buildings three and four and five centuries old. By the time the RAF was through, more than 200 acres had been destroyed by fire, and 15,000 people were homeless, 300 dead, and nearly 60 percent of the buildings in the city either damaged or completely destroyed.

Back in December 1940, Harris had witnessed the worst of the Blitz in London, including the incredible sight of the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral “standing out in the midst of an ocean of fire.” Turning to a friend, he remarked of the Germans, “Well, they are sowing the wind.” (See WWII Quarterly, Fall 2016.)

With Lübeck, the Germans were now reaping the whirlwind, and the incendiary bombs that had been used on the English city of Coventry were now dealt back to them. For the month following Lübeck, Cologne and Essen were attacked three times, Hamburg and Dortmund twice, and Rostock four nights in a row, beginning on April 23-24.

The German response began the very first night of the Rostock bombings, when they hit the city of Exeter. On the two nights of April 25-26 and the morning of the April 27, the Luftwaffe came to Bath. German directives issued 10 days earlier clearly stated that, when choosing targets, “preference is to be given to those where attacks are likely to have the greatest possible effect on civilian life.”

The first flares were seen over the city around 11 pm on Saturday, April 25, as approximately 90 German planes descended upon Bath. The night was the kind that cities all over England and Germany had begun to fear: clear and illuminated by a full moon.

The Luftwaffe began by attacking the gas works on the west of the city, whose explosions would be a guide for later bombers. As the attack began, those still on the street in Bath were so ill prepared to recognize the signs of a bombing raid—and the unlikelihood of Bath being attacked no doubt overlapped and encouraged that ignorance—that they assumed the nearby city of Bristol, a frequent victim of such raids, was being attacked again. After the warning siren was sounded and the local fire brigade dispatched for Bristol, the real situation began to dawn on the city as one fireman rode past his own house already in flames.

With telephone lines down, the situation quickly became confused. Since the 1937 Air Raid Precautions Act (ARP), some form of organized civil defense had become a priority in British life; but as such preparations were costly, time consuming, and looked forward to attacks which, at the time, were only possibilities, the ARP arrangements for many cities were improvised at best, and few cities thought it worthwhile to pool information to discover which measures might work best. Many small measures, however, had been undertaken, such as removing the railings from the disused St. Mary’s Churchyard and melting them down for munitions.

When the war began in earnest, it can only be imagined that if fire wardens in London sometimes found themselves bored, by 1942 fire wardens in Bath must have been completely disinterested, still waiting in their foxholes for a charge that never came. And indeed, on the night of the first bombing only some of the fire wardens slated for duty had shown up, and many of the initial residents whose houses had been bombed refused to remain on the scene to help put out the flames. One member of the civil defense who did appear for duty, not wanting to abandon his wife at their home, left her at the home of his sister and was never seen again.

Thankfully, one area where Bath had been prepared was in the construction of a handful of public shelters strewn throughout the city, and it was to these places that many people fled. Others retreated to their cellars, or to the private shelters installed early in the war on one’s premises—such as Anderson shelters, which occupied the underground of many a home’s back garden.

One woman, Annie Marks, recalled gathering up her mother and was going downstairs with another elderly woman in her building when a window exploded in their faces. The house next to hers had been destroyed, and inside a mother and her six children had all been killed, the father away in the army.

Many people, however, were just unsure of what to do and, whether in a desire to be in a crowd, or not wishing to take the chance that their home might collapse on top of them, scores of people filled the streets in a desperate run for the public shelters few probably thought they would ever have to use. One woman recalled the bombers flying so low she could see one of the crewmen’s faces in the glassed nose of the plane.

Others recalled the same unnerving sight of the bombers flying so low they could see the men inside; for such people the bombing became personal, and they emerged with the feeling that the bombers had been seeking them out specifically.

When the first all-clear sounded shortly after midnight (to be followed by another after 1 am), the residents of Bath found themselves engaged in a very London activity—as if the destruction weren’t real, or was at least happening to someone else’s home or someone else’s street, many emerged from wherever they had been, curious, and were drawn to watching all the fires.

One group, among them a family now homeless, had tea in the house of strangers at around three in the morning. Many who had not had the time—or nerve—in the midst of the bombing to seek a public shelter now did so, while many of those already ensconced in public shelters decided to remain there for further instructions.

One story is told of the Poole family, a mother and father with their visiting son and daughter-in-law. While remaining at the parents’ home during the raid, after the all-clear the young couple decided to seek out a public shelter on Stanley Road. Once there, and just as the daughter-in-law and her husband were about to leave for their own home, the shelter exploded.

Among many others, Mr. Poole was killed instantly, and his wife soon died of her injuries. The son survived, but not his wife. As it turned out, more than half of the Luftwaffe force that had just attacked Bath had been refueled and rearmed and immediately sent back from their bases in northern France. At 4:35 am, the warning sounded again, and the fires from the previous attack now acted as the most natural beacon for the Luftwaffe to follow.

In another shelter, a farmer who had left his family to quickly go home and check on the status of the pigs, returned to find his entire family killed. More than 30 people died at that shelter, on Rosebery Road. Had they stayed at home, they might have survived, but then the opposite was true for those who lived on Victoria Road, where upward of 40 to 60 houses were destroyed. These houses, however, were empty, and dozens of lives were saved because they sought out a public shelter rather than stay at home.

The senselessness of war, the fog and cruelty of chance and of seemingly random decisions that quickly revealed themselves to have meant life or death for so many—such situations, to which the ordinary soldier became inured and sometimes even indifferent, were now thrust upon the people of Bath, who had little preparation for it. Defenseless as the city was, about all anyone could do to help was save the lives of others and try to put out the fires.

As morning dawned and a strange new Sunday began, the people of Bath took a lesson from other cities and tried to keep busy. Yet everything pointed to the evening, since it seemed a foregone conclusion that the Luftwaffe would return once again. Throughout the day and into the night, some 10,000 residents left the city for the outskirts and surrounding hills, to sleep in the open countryside. Others hid out in caves, mines, or railway tunnels.

But by midnight there was nothing, and one group of people decided the risk was worth taking and went back home, where it was at least warm. Only a few minutes later, shortly after 1 am, the siren sounded and they were out the door again, running and finding cover in the first ditch they could find.

Owing to a greater reliance on incendiary bombs, the fires on Sunday night were even worse than the night before, and many buildings that had merely been torn through on Saturday were now ablaze.

One of these was among the most beautiful Georgian buildings in the city, the historic Assembly Rooms, which since the 18th century had been frequented by statesmen and artists alike, including Jane Austen and Charles Dickens.

The pride that people took in their history and architecture comes out in the words of Harvey Wood, only a few days after the attack: “My family and I have lost our home in the blitz, but I at least lost far more. Words cannot express my sense of loss. I loved the Rooms.”

The neighboring Regina Hotel also took a hit; 20 people were killed. While the Assembly Rooms were later rebuilt, others buildings, like St. Andrew’s Church, were so badly damaged that they had to be torn down. Somehow Bath Abbey (whose oldest sections dated to the early 12th century) and the Roman Baths emerged intact, although the former did have one of its stained-glass windows blown out.

The all-clear sounded at 2:45 am, and as the days progressed it was determined that the damage had mostly been to residential areas, with more than 15,000 houses damaged, a thousand of which could no longer be lived in, and more than 300 destroyed completely. With a few exceptions, Bath’s business center and historical buildings—and even those sites deemed military targets—survived.

Despite German claims of more than 6,000 dead, only around 400 people actually died over the two nights—and using the word “only” shows how easy it was to dismiss what they had gone through. The London Blitz, spread out over months as it was, killed nearly 30,000 total.

Upon hearing of the Baedeker Raids, a survivor of London coldly remarked, “I think it was about time they had something to make them realize there’s a war on.”

But it was just because Bath wasn’t a city like London or Dresden or Tokyo that the damage inflicted was actually far greater than anything that could be tallied. Bath never had the “luxury” that Londoners did, who banded together and found new rhythms and habits of daily life through the extended weeks and months of the Blitz.

There and elsewhere, many people were bored, or, after a lull in the bombing, found themselves “relieved” when the attacks started up again. Home Intelligence Reports are filled with observations like these: “Complacency in some districts because anticipated German attack has not materialized.”

Indeed, the more attacks there were, the less people were afraid of them; as one writer remembered it, while giving a poetry reading in London Edith Sitwell stopped as the sound of a bomb neared and passed by, and then “merely lifted her eyes to the ceiling for a moment and, giving her voice a little more volume to counter the racket in the sky, read on.”

Spared the widespread destruction and huge death toll of the London Blitz, Bath’s citizens seem to have experienced the worst of it in concentrated form, over the course of only two nights.

As one traveler who came to the city soon after the attack recalled, “When we arrived in the town, the general impression we obtained was that it had more or less ceased to function as a town in the normal sense. The mass of the people had become quite detached from their normal routine, and had not yet found any place in the new situation; their only outlet was in wandering around the streets or to the various aid bureaus, or seeking some means of getting out of the town…. They seem faintly nervous and agitated; there is a tendency to repetition of the same story. They obviously have not settled themselves down or become adapted to bombing.”

The story of another survivor is also indicative. Florence Delve had been able to escape with her husband and two children on Saturday, even as their home was destroyed. When a neighbor was pulled from the rubble of another house and died in Florence’s arms, she went into shock and was unable to nurse her baby.

A tense Sunday evening was spent in a stupor, trying to care for her children. She then walked with her husband and children to Bristol, some 12 miles away, so she could catch a train to South Wales, where her mother received her—still covered in the debris of the attacks, her clothes dusted in plaster.

Of those who remained in the city, many walked out into the countryside again on Monday night, in case the attacks continued—after all, a German reconnaissance plane was seen over the city that afternoon, and many assumed it a prelude for more that night. A rumor also spread that an evacuation of the city was being ordered for the evening, and although this wasn’t true, many fled however they could; as it got darker, those waiting in line for a bus out of town began to panic again.

As it turned out, and despite the new antiaircraft guns that also dotted the surrounding hills, the Luftwaffe did not return. They had other appointments in Norwich and York and Canterbury—and in the last of these, learning the lesson of von Stumm, the Germans lamely claimed that the military target there had been the Archbishop and his apparently egregious “incitement campaign against Germany.”

As early as April 29, 1942, the question of intentionally bombing civilians came up in the House of Commons. When one Member of Parliament (MP) wondered aloud whether the recent RAF targets in Germany had been primarily military, the repeated response was, “What about Bath?”

Another MP asked, “Has the Honorable Member not heard of the pictures we have of the damage of our great cities, and does he know how the morale of our people is inspired when they see that something similar is being done elsewhere?”

Another MP, nearly seeming to admit what was going on but justifying it as an expediency, said, “The best way to prevent this destruction is to win the war as quickly as possible.”

The simple ability to name an act of war regrettable but also necessary only seemed possible in private; Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” recalled the American Secretary of War Henry Stimson being appalled “that there should be no protest over the air raids which we were conducting against Japan, which in the case of Tokyo led to such extraordinary heavy loss of life. He didn’t say that the air strikes shouldn’t be carried on, but he did think there was something wrong with a country where no one questioned that.”

Hitler claimed it was the British who had first determined to bomb civilians and threatened “a reply that will bring great grief.” But, by and large, this reply never came, and in fact the reply was unleashed on the Germans in the firebombing, most notably, of Dresden in early 1945, which killed more than 30,000 people and left a quarter million homeless. Advances in technology were put to their most complete use in the fire bombings (and finally atomic bombings) of Japanese cities.

One of the few historians of the Baedeker Blitz—and indeed it is a neglected corner of the war—has written recently of how few plaques or memorials to the bombing have been put up in Bath or the other cathedral cities. The uneasiness of civilians coming under fire is still too difficult for many to deal with, since it means that at some point any of us might be put in such a position.

However, mention should be made of the Remembrance Book kept in Bath Abbey. Housed under glass and looking like an illuminated manuscript a thousand years older than it actually is—including historiated initials, twisting green and orange leaves climbing the margins, and the names and addresses of the dead in black and red ink—those who died over the two nights of bombing are listed alongside the locals who died in battle elsewhere.

That seems the most appropriate remembrance of all, since despite being far from the front lines, they died in battle too.