By Joachim Benz, as told to Peter D. Fyfe and Ward Carr

Following service as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Air Defense Artillery during the early 1970s, Ward Carr decided to remain in Germany, residing in Frankfurt. He has worked as a language trainer, freelance journalist, and translator. In 2001, Carr and a German colleague began writing a book featuring the crew of the famous battleship Bismarck. While searching for survivors and family members of Bismarck sailors, Carr often encountered veterans or family members of veterans who had served in the German armed forces during World War II. Although they may not have been associated with the Bismarck, many of their stories were nonetheless fascinating.

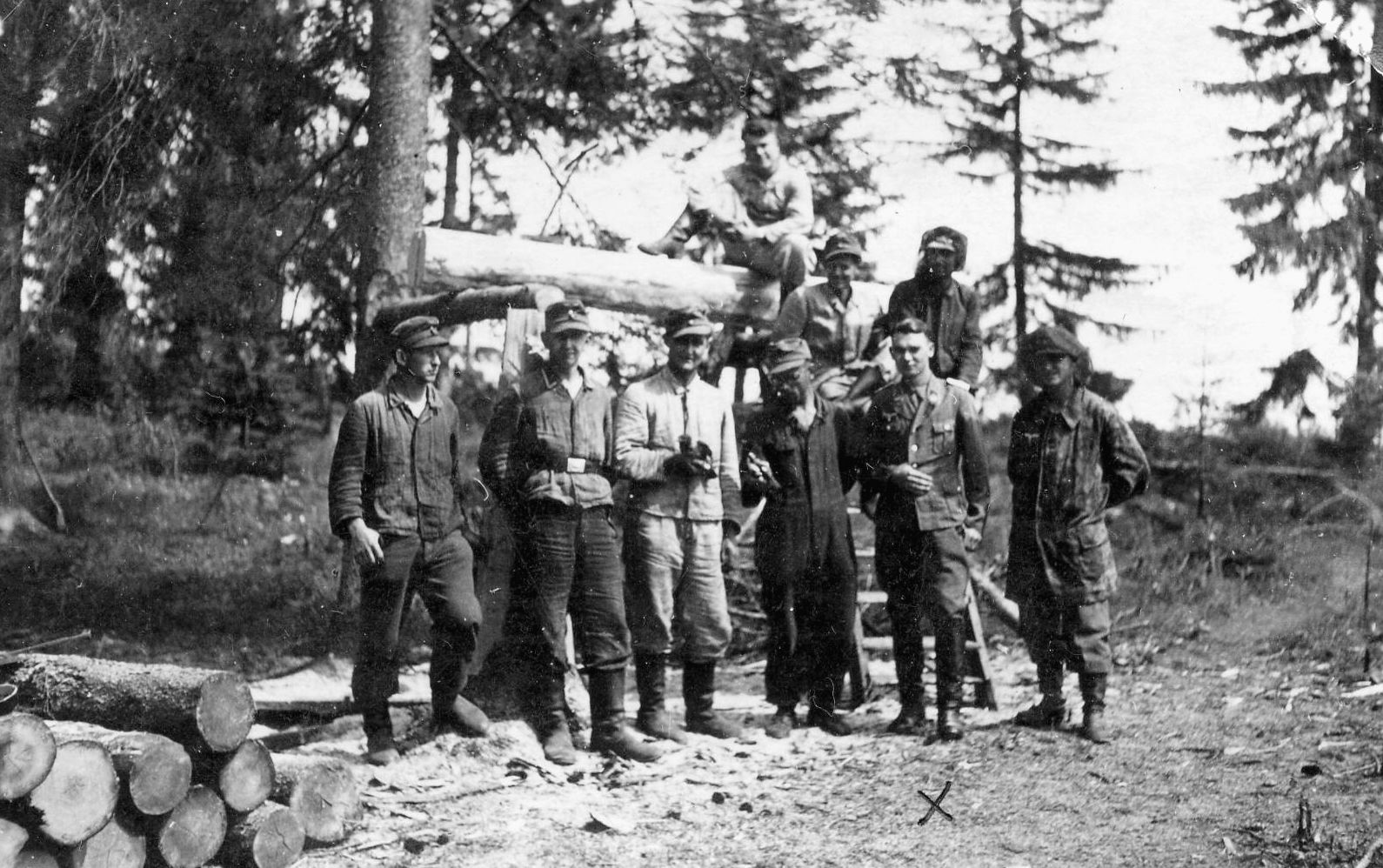

During the course of his research, Carr placed an ad in a national veterans’ magazine. Joachim Benz was one of those who responded. Over a period of several years, the two communicated often by telephone and visited one another. Benz has contributed oral passages, comments, and photographs for publications, and a German-language book of his memoirs was published in 2003. The photographs in this article were all taken by Joachim Benz with a Kodak Junior camera that he got as a confirmation present.

As a student at the Virginia Military Institute in the 1960s, Carr had learned German from Peter Fyfe. The two renewed their acquaintance in the 1990s, and Fyfe contributed his translation skills to numerous projects, including the interview with Benz, which formed the basis for this article.

Benz tells an interesting story of combat with a Luftwaffe field division. After the war, he worked on a farm for two years before opening up a grocery store and delicatessen in Bad Arolsen in the German state of Hesse. He has often met with buddies from his former flak regiment, many of whom were prisoners of war in the United States after their capture with the Afrika Korps. Although he has tried repeatedly, he has never been able to get in touch with anyone from the 3rd of 4th Luftwaffe Field divisions.

The Story of Joachim Benz in His Own Word

On the Eastern Front

I was born November 13, 1922, in Hamburg, Germany. I had a happy childhood with my older brother and two sisters. I wasn’t very gung-ho about it [the Hitler Youth]. I preferred playing soccer or going to the movies. Once, a policeman and the Hitler Youth leader came to pick me up because I hadn’t reported to drill.

In November 1940, I was called to the colors in Hamburg. Then I was drafted into the RAD [National Labor Service] on February 2nd, 1941. Our basic training was in Cammin/Tessin, Mecklenburg, and then we were sent to a little village in Poland about 50 kilometers east of Warsaw. It was directly on the demarcation line [between Germany and the Soviet Union]. We constructed a munitions depot for bombs and built roads to the depot. At the beginning of June 1941, we were transferred to Lyck, in East Prussia, where they armed us with old French rifles and trained us. Since these rifles were very long, the 4th Platoon got Dutch carbines, which were very inaccurate because they were so short!

Later, in Russia, we exchanged these useless arms for captured Russian weapons. The Russian carbines resembled our 98Ks but did not have safety catches. In addition, every platoon was issued a Russian machine gun. They were extremely heavy, and we called them “The Gramophone” because the magazine was round, lay flat on the barrel, and rotated.

Right after the war with Russia broke out, we were deployed to guard a forward airfield east of Vilnius [Lithuania]. After Minsk fell, we were redeployed there, where we had beautiful quarters in a large, multistoried building of a former uniform factory. We were detailed to guard captured material and an airfield. Our unit was assigned to the Air Force Central Command. There was material of German origin among the captured booty. The uniform manufacturing plant was furnished with German Singer sewing machines. At the Russian airfield we found, fresh from the factory, BMW rear-propelled airplane motors in the original boxes. In one room of the uniform factory there was a German grand piano. We used this room as a movie theater to show films, a very welcome change for us. I should also mention the magnificent Opera House in Minsk, which was richly decorated with marble. There were many other big, splendid buildings on Lenin Square.

The winter of 1941 came very early; on October 6, we had the first snow, and our equipment was not suited to this climate. In the middle of December, we were transported by rail back to a town in Mecklenburg and were released from the RAD two days before Christmas.

Actually, duty in the RAD was pretty good. We were all the same age and almost all of us already knew one another either from school, the Hitler Youth, or from sports clubs. However, our leaders were not the pick of the litter. Our commander was a gnome, and not just physically. He was an extremely corrupt man and diverted a part of our rations. Whenever he was annoyed with us, he did not salute us at the morning formation and said we were not worthy of being greeted with the name of the Führer!

On January 15, 1942, after a four-week leave, we were absorbed into the headquarters battery of the Reserve Antiaircraft Division 62 in Oldenburg. Here we met almost all of our old friends from the RAD again. We were a bunch of old Russia hands, which could not be said of our trainers. We were all trained as radio operators after a test, which I passed with the help of my pals from the RAD. Actually, I was a bad signalman. Up to a certain speed I was okay. After that, I could not tell the dots from the dashes. You had to have a pretty good musical ear, and I did not.

After basic, we were ordered to the Air Force Communications School 5 in Erfurt. After eight weeks we took our radio operator’s exam and went back to the reassignment center. Unfortunately, our old group was broken up. I was sent to Rostock and assigned as a radio operator to the heavy antiaircraft battery, the 88s. We protected the Heinkel airfield where the new jet fighter was tested in August 1942.

Reassignment to the Mediterranean

In October 1942, our unit, the 9th Antiaircraft Regiment (Motorized) was reassigned to the Afrika Korps. At that time, however, I was in the hospital with a serious pleurisy infection. After my release and recuperation leave, I reported to the Antiaircraft Replacement Section in Rosenheim to rejoin my unit, which was already fighting in Africa. But I only got as far as Caserta/Naples in Italy. It turns out my buddies who made it to North Africa had a great war later as POWs in the USA. They could go to classes there and so on.

Things had gotten so bad because of Stalingrad that the Luftwaffe had to assign its ground divisions to support the army. Therefore, at the end of January 1943, I was transferred to the Air Force Ground Division and went from Italy to the Munsterlager reassignment center in north Germany. [Munsterlager was a reception, troop distribution, and training center. It also served as a reception center for German POWs returning home after the war.] This reassignment was a real shock, for it was back to Russia, again. It had been like spring it Italy—over 60 degrees. In Russia it was zero.

Our division commander was Lieutenant General [Robert] Pistorius. I did not know him personally, but then again I never saw any general on the front lines. He signed the attestation for my Iron Cross, Second Class. Later he took overall command when the 3rd and 4th Field Divisions were merged in 1944. He later fell in the Vitebsk Pocket.

Our regimental commander, Colonel Windesch, whom I knew personally, was an extraordinarily brave and upright superior. A forester by profession, he was an elderly, fatherly figure. He visited frequently on the firing line and the forward observers out front. Once during a visit at the gun emplacement he asked me if the rations were satisfactory. I said no. He was amazed to find out that I, as a soldier under 21, was supposed to get the supplementary rations. I told him that our battery commander, by his own admission, issued these “children’s” rations to everyone. The colonel saw to it that supplementary rations were directly distributed to those entitled to them. A short time later, I was rewarded for this by my battery commander by being lent from the gun emplacements to the forward observation posts.

Our battalion commander was Major Meyerkort, who had been a tropical fruit importer in Hamburg before the war. He was a beloved leader among us soldiers, with a lot of courage. He wore a leather uniform without rank insignia so we called him “Leatherstockings.” Major Meyerkort visited us frequently at our forward observer posts. He also regularly inquired about our wishes and concerns. Major Meyerkort fell into the hands of the Russians in June 1944, and died in Baku of dysentery. It is interesting that the major is said to have had a Russian mother and to have been born in Baku, and he spoke Russian. His captivity in Baku was certainly not an accident, and so I doubt that he really died of dysentery there!

We had several battery commanders in a short time, and they all seemed to have only one thing on their minds: to be reassigned to Germany or France as quickly as possible. Number one was 1st Lieutenant Sauer. He was our commander for about five months; then he was transferred, I assume, in the direction of the homeland. I was with him at battery headquarters for several weeks, and we often played chess together. After I beat him once, he stopped playing me. He was really a very vain man. Number two was a 1st Lieutenant Werner. I believe he came from Hamburg. Twice we played soccer together in Battery 11. He, too, was transferred after a short time, probably back home. Number three was 1st Lieutenant Lohse. He probably was lost with the battery in June 1944. We hardly ever saw these three gentlemen at the forward observer positions.

Our other officers were 2nd Lieutenant Müller, deputy battery commander, and 2nd Lieutenant Streib, a law student from the Saarland. Our platoon leader was Master Sergeant Hermann. There was a private with us, Gerhard Schubert, whose father was a general. Gerhard was later killed in action.

Disadvantage in Equipment

When we got to the reassignment center in Munsterlager at the beginning of February 1943, we went through a three-week orientation course as artillerymen. My new unit now was the 5th Battery, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Artillery Regiment.

I was assigned to the calculating section as a tabulator. The section leader was Corporal Setz, a teacher from Austria. We were supposed to calculate the weather and other influences four times a day using logarithm tables. We received the numbers for the evaluation four times daily from the weather bureau. Our battery was equipped with four 75mm pieces. These guns were captured French war booty from World War I. The date “1916” was engraved on the barrels. Since we were a motorized unit, the gun barrel had been mounted on a 50mm antitank gun carriage. The 50mm antitank gun had been taken out of service in Russia since its projectiles could not penetrate the Russian T-34 tank. We called the 50mm antitank gun “door knocker.” The carriage was not much use either.

The 75mm gun had a range of about 12 kilometers. If we shot over nine kilometers, we had to be careful not to break the crossbar, because at this elevation the recoil was directly on the weak crossbar. The alternative was to dig a hole under the back of the carriage. From the outset, we were clearly at a disadvantage with this weapon, and indeed with all our equipment.

“Direct Hit! Take Cover!”

In mid-February, our convoy left for Russia. After a seven-day journey through East Prussia and Lithuania, we reached Newel. Then we were off-loaded and drove through bitter cold and a snowstorm eastward to our assigned position. We soon discovered our equipment was unsuitable. The roads were as smooth as glass and the tractors were completely worthless. The iron tracks slipped on the smooth roads. The bolts on the treads came off, and the tractors were left stranded on the road without treads. Our “Lanz” tractor that was supposed to help us out in difficult situations was also useless. It had ironclad wheels and could not keep to the roads. We had to leave these brand-new tractors sitting in the ditches. Thanks only to our Opel all-wheel-drive trucks, which performed excellently in all weather, were we able to reach our destination to the south of Welicke-Luki.

We had just arrived at the front when the guns were immediately positioned and aimed, and we had to start firing. The Russians welcomed our forward observers over a megaphone, saying, “You half-trained Luftwaffe soldiers straight from Munsterlager repo-depot, we’ll whip your asses in no time!” This showed how well informed Ivan was!

Our computing section was quartered in a farmhouse only a few meters behind the guns. At the first salvo, the window pane blew out on our card table, and the battery commander was lying on the ground shouting, “Direct hit! Take cover!” Then we found out that the damage had been caused by the reverberation of the recoil of our own guns. After a few days our battery was transferred to the east of Newel, about 10 kilometers from Uswaty. We were located on the firing line close to the village. We stayed there for a half year.

At first, we support troops were quartered in “Finnish huts,” big round structures made of plywood. About 20 people could live in these things. Since the Russians quickly spotted us, we soon received nuisance fire from a 172mm battery. The shrapnel from the shells penetrated one of our cabins, but, thank God, there were no casualties.

We called the 172mm guns “black sows” because the shells produced a big black cloud when they exploded. Another Russian artillery piece was the 76mm cannon, which we called the “creaky bang.” Because of its high muzzle velocity, you heard the sound of the explosion before the sound of the firing. This extraordinarily effective weapon was developed in Germany by Krupp. The Army artillery experts had rejected this gun because the muzzle velocity was too high, and thus the cannons were sold to Russia.

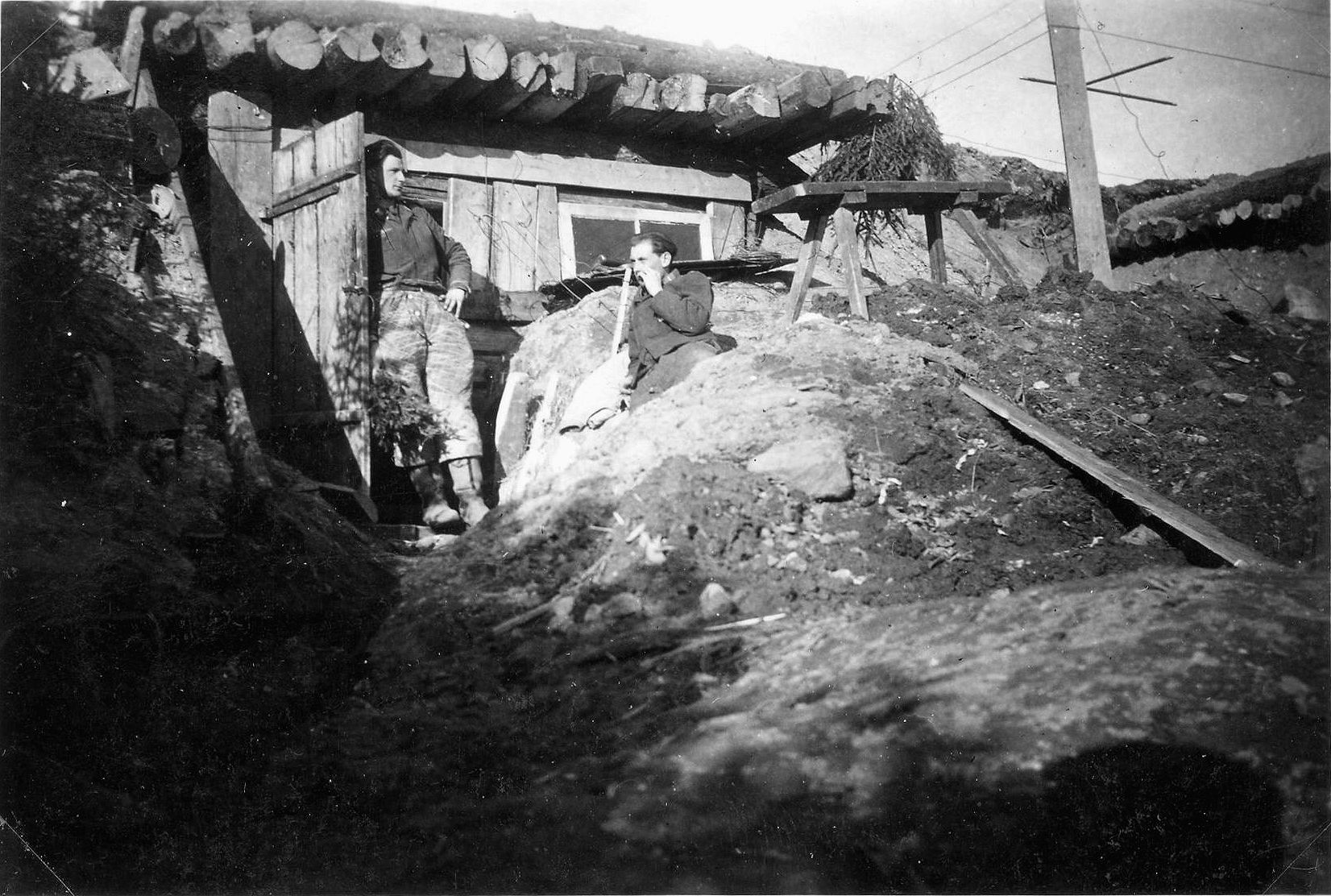

At the end of March 1943, we revamped the artillery position so that we could defend it in all directions. Every gun crew and the battery headquarters got individual bunkers. Building bunkers at this time of year was very difficult since the ground was frozen solid. Frequently, we had to blast, and because of the shortage of proper explosives, we used mines. There was a trench around the entire artillery position with a 15mm antiaircraft machine gun emplacement that was supposed to protect us on all sides. At that time, the front was extremely quiet. Only the partisans were making pests of themselves behind the lines.

The Propaganda War

Now we had the time to learn more about our guns and equipment. In addition, we fired in our barrage areas. Air activity on both sides was minimal, aside from reconnaissance flights. The Russians tried to recon our lines using a captive balloon until one of our fighters shot it down. Once we saw Russian fighters shoot down a German Focke-Wulf double-bodied reconnaissance plane. On the very next day, a German Army communiqué announced: “Yesterday ‘X–number’ of Russian planes were shot down without loss to us!”

Up on the front line Ivan used megaphones to make almost daily announcements like “Stalingrad [is a] mass grave site,” or he invited us to desert. “German soldiers—desert! The most beautiful women in Leningrad await you. You will have regular sex. Bring two mess kits along, one for pudding.” I do not know of a single German deserter, but Russians often deserted to us. These announcements were made by Seydlitzers, members of the National Committee for a Free Germany, Stalingrad prisoners.

[Lieutenant General Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach, captured at Stalingrad, joined several other officers in forming the Association of German Officers and the National Committee for a Free Germany. Opposed to Hitler’s management of the war, they hoped to gain some leverage with the Soviets for Germany after the defeat they expected. The organizations created and supported propaganda efforts aimed at convincing German soldiers to surrender to the Soviets.]

A Calm Front

I became a forward observer in mid-1943. Our computing unit was broken up, so I lost my cushy position as a calculator. They figured out that the consideration of unusual and climatic factors is redundant for light artillery. I was assigned to the forward observers because our forward observers— despite the general lull on the front—had suffered serious losses from Russian snipers. The artillery position occasionally had to provide a gun to combat the partisans. Here, too, we had losses. Almost every night so-called “sewing machines,” old Russian biplanes, flew over us and dropped rations and munitions to the partisans, especially in the Lapel area.

Because of the partisan activity, resupplying was difficult. A lot of supplies were lost—mail, food, and munitions. Only when our supply trucks drove in convoys protected by armored reconnaissance vehicles did the supply situation improve. Since the summer of 1943 was very lovely and the front was calm, we built a soccer field and scheduled games against other batteries. The area around Uswaty was very level. We could see a large white house through our artillery range finder—maybe it was a palace. And there was a lake in front of Uswaty.

During the breaks in the action, movies and theater came up near the lines, so that the guys had a little diversion. There was a barn, which they used for these performances. Every unit could release a certain number of men to attend these performances. Of course, the positions had to be battle ready at all times. The Russians quickly found out about these shows and shelled us during one performance with a 172mm gun. We immediately ran out of the barn and took cover, so there were no casualties. The shells hit right near the barn. A dancer got hysterical, and our medical officer, famous for his rough manner, treated the poor girl with a slap in the face and the words: “Go behind the barn and piss yourself dry!”

An Attack on Christmas Eve

In the fall, the front got livelier. To the left and right of our sector, the Russians made major breakthroughs, so at the end of October we had to abandon our beautifully built position without direct contact with the enemy. The time of straightening the front began. New fronts had nice names like Panther, Tiger, or Bear Position. But now these positions were just simply strongpoints. There were no longer solid, unbroken front lines. Furthermore, these strongpoints were much too thinly manned. The enemy could attack us from all sides.

Shortly before Christmas 1943, we took up a position east of the road from Vitebsk to Nevel. On Christmas Eve the Russians attacked. It was very cold, and an icy snowstorm was raging. Ivan broke through left and right of our position, and our battery was ordered to abandon its position as quickly as possible and get back to our new lines to avoid being cut off.

We had been looking forward to a happy Christmas Eve in a warm bunker! We hurriedly loaded our equipment, range finder, radio gear, and machine gun on our motor sled, which looked like a little boat, and sped off to the west. Toward midnight, we four sat under the open sky and sang the Christmas carol, “O Du Froehliche…!” We reached our lines on Christmas Day, and—what a miracle—we even got a bunker, which we shared with six infantrymen. We artillery forward observers were very welcome guests, for we all had our tommy guns and a 15mm machine gun. We also had hand grenades and armor-piercing antitank grenades. We were supposed to hold this position—I think it was called Position Panther—at all costs because it protected the Nevel-Gorodok-Vitebsk road.

Driving Back Russian Attacks

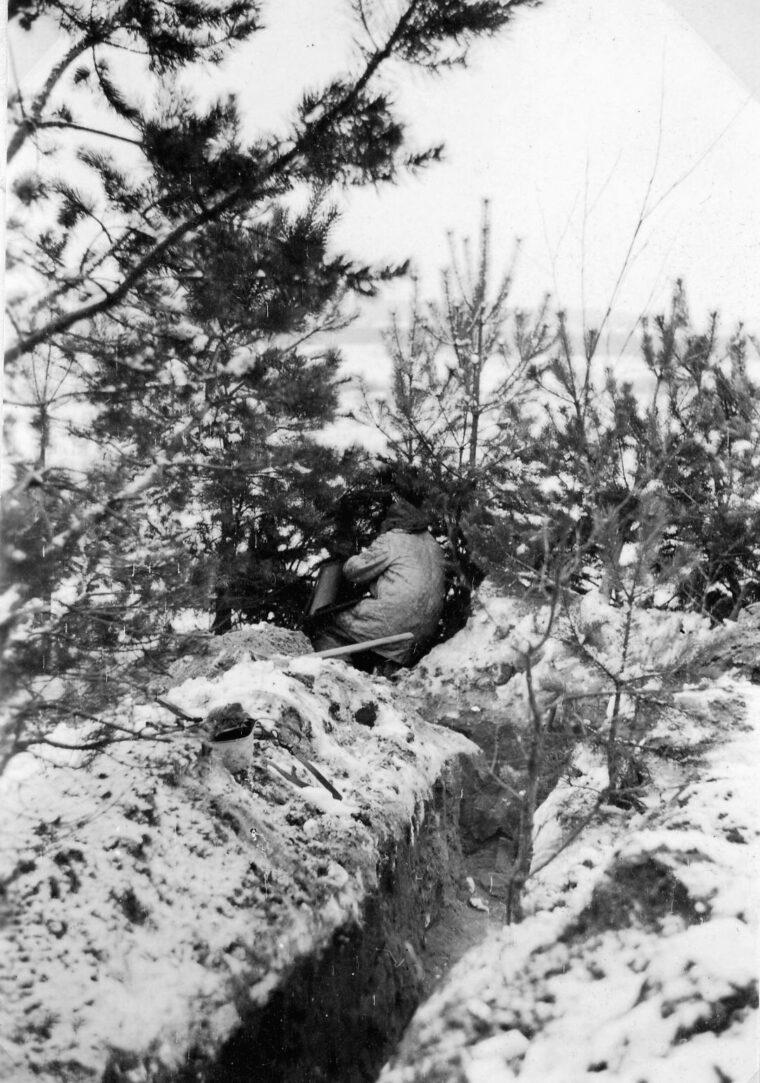

In the beginning of January 1944, the Russians attacked almost daily without any noteworthy success. Our battery and forward observer line were transferred to the northeast of Vitebsk, in the Dvina River bend. Our forward observation post was located on a bald knoll, an ideal place for defense. The knoll was about six meters high and very steep, scarcely negotiable for tanks. The limestone was so hard that our trenches were only a meter and a half deep.

During the day, we could only move around in them bent over, almost crawling. The enemy positions were only 150 meters away, and the Russian snipers were damned good; in a few days we had three men killed. We used mirrors in the trenches to see what was going on. If you put a helmet on a pole and put it into view—pow—within minutes a Russian sniper would put a hole right through it. The duty was rough because a forward observation post like this had only a four-man crew, and since we had double guards at night, we had to go on guard every two hours. It was better during the day since we had only one guard on watch at a time, so you only had to fall out every six hours. Several attempts by the Russians to storm our position failed. We held it with our forward observers with the help of 10 infantrymen. On April 4, 1944, a Russian shock-troop unit managed to penetrate our position. Naturally, it was when I was there all alone!

However, I was able to fight off the Russian attack with hand grenades and a light machine gun. The infantrymen from a Brandenburg unit and my three comrades fought through and got me out. Accurate fire from our battery caused the Russians additional severe losses. There were three men killed just in our position alone. We all got the Iron Cross, Second Class and were credited with a day of close combat on our records. Our battalion commander, Major Meyerkort, visited us a few days later and treated us to a big bottle of vodka and cigarettes. In general, vodka played a big role in this period. We got a cup of vodka with a quarter liter of schnapps daily. The rations were better this winter, when the supplies reached us. One of the infantrymen was a barber from the same town in Brandenburg as my father and actually knew him. A small world.

Iron Cross Training

I remember seeing the Stuka pilot Rudel at work. [Hans Rudel, a Luftwaffe colonel, was the most highly decorated soldier of the Third Reich. He piloted a Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive- bomber and flew 2,530 missions during the war and destroyed 532 tanks. In September 1941, he sank a cruiser and the battleship Marat.] Whenever things got tight, we called for the Stukas because we could not stop the Russian tanks with our 75s. They were too well armored. We could use a special armor-piercing charge, which was placed on the muzzles, but they were not accurate. So we called for the Stukas.

Rudel approached the tanks from the rear because the armor there is weakest, it being over the motor. Then he blasted them with the cannons. Since Stukas were very slow, he was always protected by two ME-109s [fighter aircraft]. It was always a great relief for us when we saw the plane with long cannon barrels protruding from the wings approaching. The cannons looked like broomsticks.

Another thing I remember is the ensigns—officer candidates—at the front. They had to spend a certain amount of time in a combat zone. We called it “Iron Cross training.” Since the Russians were always shooting at us or sending raiding patrols out, the ensigns would have to come to us for contact with the enemy. When they had gone through an attack, they would be given an Iron Cross and could return to whatever school or course they were attending.

One time a raiding patrol attacked, and an ensign was there with us. He wanted to report the action to the colonel, but he was so excited and nervous that the colonel simply said, “Just give me Private Benz.” And I made the report; it was nothing new for us.

R&R in Hamburg

At the end of January, I got three weeks of R&R. It was a difficult and dangerous journey through the rear area, and many a soldier lost his life on the trip home. The partisans harassed the rail lines with gunfire and explosives. There were destroyed cars up and down the rails. Our train was protected by a 20mm cannon and several machine guns. We were glad when we reached the border at Wirballen, where we were deloused and given a “Führer’s food pack.” [This was a special package given to front-line soldiers for their home leave. It contained items such as butter or margarine, sugar, coffee, chocolate, etc., which were almost impossible for the normal citizen to get.]

I hoped for a new uniform since mine was all torn up and really filthy, and my underwear had not been washed for four months. But because the Luftwaffe ground division was now under the command of the Army, neither the Luftwaffe nor the Army felt responsible for me. So, they let me go home to Hamburg in this condition. My parents had been bombed out in Hamburg, and I had no clothes back there. It was only thanks to my clever sister that I was able to spend my leave in a clean uniform. She got me the new uniform and underwear at a shop for antiaircraft personnel. I had a wonderful leave in Hamburg. My family was housed in a Hitler Youth dorm. But I was furious over the destruction to my hometown.

A Forward Observer Course

Back at the front we were still in our old position on the Dvina, northeast of Vitebsk. Just outside the city, the train was shelled from both sides by Russian artillery. The corridor to Vitebsk was getting narrower and narrower, and it would be just a matter of time until the Russians shut the trap. I did not hear any cheerful news when I arrived. We had suffered substantial losses, particularly in the forward observation posts. Since we could not count on reinforcements from home any longer, we were slowly bleeding to death. The Third and Fourth Air Force Ground Divisions had been merged in the meantime and were now called the Fourth Air Force Ground Division. General Pistorius was in command.

The old routine began again—manning the station at our forward observation post. The Russians were always coming up with new ideas to make life miserable for us.

It was April 1944, and at this time of year the Dvina was still running high. I had just come on duty one day when a rather large, unmanned barge came floating down the river. I began firing at it with the machine gun when it passed our position, but I could not damage it. So, I reported it to our battery commander, and he ordered a gun on the Dvina brought into position. When the barge came level with the cannon, it was shelled. It blew up after a direct hit. It had been loaded with explosives and was supposed to blow up the Dvina Bridge at Vitebsk. One artilleryman was wounded by the tremendous explosion.

In May, Russian reconnaissance activities increased. It was clear that Ivan was planning an attack. Although we could observe the Russian activities, we were not permitted to fire. We had to save our ammunition. Our vulnerable position worried us because the Russians would quickly tie the noose around Vitebsk if they attacked. So, I was overjoyed when I got orders at the end of May to attend the artillery forward observer course in Lepel.

This order did not make sense to me. They wanted to make me a forward observer officially. But I had been directing artillery fire for several months as an assistant observer, and especially when our forward observer, Corporal Ditmann, had been killed. But it turned out that these absurd orders saved my life. On the way to the course I met another fellow from Hamburg, Corporal Louis Petersen, who had been ordered to the course too. We hit it off right away and have remained friends ever since.

Most of the people in the course were sergeants or corporals; I was one of the few Pfcs. On June 7, 1944, our course leader, a major, informed us that the Allies had invaded France. He made a very daring statement: “If the Allies are not repulsed in a few days, then the war is lost.” How right he was!

On the Retreat and Under Fire

Shortly before we finished the course, the Russians started their offensive. Vitebsk was quickly surrounded. We were all assigned to fighting units. Petersen and I were attached to the crew of an old 105mm howitzer with ironclad wooden wheels. It had no sights, and we had to aim point blank along the gun barrel! So, off we went, six men plus cannon toward the East, and we were supposed to stop the Russians with it.

We soon lost contact with the other outfits. We neither heard from nor saw anything of our school officers. We scarcely had contact with the enemy when we were pushed aside by troops flooding back, particularly supply units. Near Glebokie we captured a Russian antitank gun with two horses and ammunition. The two-man crew escaped. They had probably lost their way and suddenly landed—to their surprise and ours—right in our location. Now there were six men and two guns. After we had fired all the ammunition for the 105, we blew it up, for there was no resupplying anymore.

Off we went with our captured antitank gun in the direction of Schwentschionen. We handed over our antitank gun to an artillery supply train since Petersen and I were now alone. The other four had disappeared during a tank attack. We two had hidden in a huge wheat field.

Then we joined up with a quad 20mm antiaircraft gun. These guns were mounted on halftracks and were really effective. The Russians had great respect for them. Usually their planes attacked convoys directly along the axis of movement, either from the front or behind. When they thought we had quad 20s, they attacked the convoy from the sides, which limited the damage they could inflict.

From Vilnius we went north. We were under continuous attack from low-level bombers, IL-2s, the Shturmoviks. Even quad 20s had trouble shooting them down. Those planes were really something, not very fast but were they well armored! Once we came across one that had crashed. Just for fun we shot at the canopy. The bullets just ricocheted off of it—did not even scratch it. And they had rear-firing rocket launchers. They would make a pass firing machine guns, then fire rockets going away. We always had to make sure to wait for a while after they passed over before coming out of cover.

“Throw Those Grenades up Their Ass”

The Latvian people were well inclined toward us and continually warned us of the pursuing enemy. The front had completely disintegrated. Supply columns, fragments of troop units—all streamed leaderless to the west. Officers were hardly ever seen. They had probably saved themselves in motorized comfort. Rations were a problem; the food stores had been set ablaze. Once, in Utena, we were able to get provisions before the stores were blown up.

On the way from Vilkomir to Kovno, two MPs on motorcycles suddenly appeared and threatened the retreating guys, saying, “Halt! Whoever retreats will be shot!” When the guys gave no sign of stopping and pointed unmistakably to their weapons, the two MPs turned around and took off.

In Kovno, Petersen and I reported to the local headquarters and were assigned to a task force. This commander obviously had a “sore throat” and wanted the Knight’s Cross at all costs. He gave us a stirring speech. His favorite words were, “When the Russians come, don’t be cowards. Throw those grenades up their ass.”

Just how we were supposed to repulse an enemy that had tanks, low-flying planes, and hundreds of guns, he did not say. After all, we were only armed with carbines. Later on, while in the hospital in Hamburg, I read in Der Völkische Beobachter [the official Nazi newpaper] that the colonel had fallen on the Eastern Front. He got the Knight’s Cross posthu-mously. I could not guess how many guys had to bite the dust for it.

While the task force was still being assembled, Petersen applied again to the local commander and actually got orders for us to report to our replacement unit in the Alsace. Armed with these papers, we left Russia with the next train heading west.

On July 13, 1944, we crossed the border after being deloused in Wirballen. After a couple of days’ travel, we reached the replacement team in Diedenhofen. My buddy Petersen was already on leave, and I was interrogated by a courts-martial officer. The only thing I could report was that we had been abandoned by our officers from the artillery school. I never heard anything more about the matter.

On August 2, 1944, I got a 16-day reassignment leave. Because of the hardships of the retreat and journey, I had come down with a serious lung infection, and so I was taken to the Reserve Hospital in Hamburg where I stayed until September 11, when I was allowed to take my postponed leave.

“Fit for Limited Duty Only”

In the meantime, our replacement unit had been transferred to Regensburg, so I reported there after my leave. On November 1, 1944, I took part in a corporal’s training course in Ansbach, near Nuremburg. After passing the exam, I became a reserve corporal candidate. Because of my illness, I was classified “fit for limited duty only” and was reassigned to another base where I was made an instructor for a corporals’ class, which consisted of men from 16 to 42 years old. In February 1945, I caught pleurisy again and was sent to the Reserve Hospital in Hamburg until March 3.

In the meantime, the Allies had crossed the Rhine. About 15 limited-duty people were sent back toward Regensburg. After a four-week foot march, we reached our reserve unit in Regensburg. The Amis [slang for Americans] were right behind us the whole way. When we arrived in Regensburg, they were already right at the gates.

Our people told us to take 30 young and almost unbroken horses from there to Landshut. Only two or three of us had ever been on a horse. It was impossible to move during the day because the enemy fighter-bombers had complete control over the roads. So we set off at night toward the end of April. Every guy had two horses, which he took turns riding. Using back roads, we went the 100 kilometers to Landshut, where we arrived one morning completely exhausted. Since we did not have riding britches—and were no horsemen—we had terrible blisters on our cheeks and were completely raw between the legs. So far in the war this had only happened to my feet!

Captured Briefly

When we arrived at the garrison, we immediately lay down on the cots and slept right through to the next morning, May 1, 1945. When we got up, we realized that the whole garrison personnel—including the officers—had run away. Once more we had been deserted by our officers. The Amis were already in the city and standing right in front of our barracks. Since we had no food, we raided the military stores, put on new uniforms, and en-tered into American captivity.

That day, I was wounded by shrapnel from a tank shell. The garrison was shelled by tanks although we had raised the white flag and offered no resistance. The Americans took us to the notorious POW camp, Regensburg-Donauwiesen. On the way there, they put us in a cow pen. When the farmers tried to bring us cooked potatoes—we had not eaten anything for 24 hours—the Americans shot at us. A buddy was hit in the thigh and bled to death. The Americans denied us any help. Thus we became acquainted with our liberators right away.

It was not any better in the Regensburg camp, where there were over 100,000 prisoners. We got scarcely anything to eat—three biscuits per day. But not getting any drinking water was really a dirty deal. Several times during the week there was a so-called roll call. We were herded from one camp to the other. The Americans stood to the left and right and beat us with bamboo canes. For weeks we lay under the open sky; they had taken away our tarps. The weather god was gracious; it scarcely rained at all. On the first of May, the day of our capture, it had snowed. Many comrades, especially the older ones, died of lung infections.

At the beginning of June 1945, rumor had it that we were to be handed over to the French to work in the mines. Now, I had to fake something. I went on sick call and told the American doctor that I had TB [tuberculosis]. The Americans were very scared of TB, so they released me quickly.

Since the Americans only released prisoners in their own zone, I gave my grandmother’s house in north Hesse as my home address. There was one final dirty trick. Those of us to be released, about 40 men from the Kassel area, had to have our heads shaved.

On Sunday, June 3, 1945, black American soldiers drove us by tractor-trailer truck from Regensburg to Kassel. We went via Würzburg and Giessen. In the villages that we passed through, the people tossed bread to us. In the evening, not far from Giessen, they threw us out of the truck and told us to walk the rest of the way.

The End of the War for Benz

It only took a few days to reach my grandmother’s house. But a couple of interesting things happened on the way. An American patrol stopped me and asked to see my papers. When they read that I had a lung disease, they gave me the papers back immediately and wiped their fingers on their pants. Then, I was walking past a former SS barracks occupied by American troops. Some GIs heard me approaching. I was still wearing the hobnailed boots, which made a lot of noise on paved roads. And they hung out of the windows razzing me, shouting “hip – hop – hip – hop” in rhythm with my boots plunking on the road.

I looked up and yelled, “Fellows, the war is over for me. You get to stay here and play soldier boy a little longer!” You can imagine the tirade of curses and oaths that came back. Finally, on June 5, 1945, just before the night curfew, I got to my grandmother’s house. For me the war was over. Although I tried for many years to establish contact with my former buddies from the Third/Fourth Air Force Ground Division, I never succeeded. I had no better luck with their relatives. All the comrades who were in the Vitebsk area were reported missing.

Interviewer and translator Peter D. Fyfe resides in Lexington, Virginia, and worked as a professor of German at Virginia Military Institute. Ward Carr is a veteran of the U.S. Army. He performed preliminary editing of the interview and resides in Frankfurt, Germany.

I read this biographical sketch with great interest, because it resembles the 1,000+ oral histories of veterans (mostly WW-II) I have conducted and transcribed (including a German immigrant to the U.S. who spent five years as a POW in Russia), or had transcribed by a small army of paid student (paid in scholarship money by the State of Utah) employees, or who got university credit for their work. I’m in the process of depositing these transcriptions into appropriate archives.

How refreshing to learn that somebody else (and probably many other oral historians) are documenting veterans’ histories. My main intended readers are the veterans’ families, though I also do the archiving.

Nearly every veteran who saw combat becomes very emotional when he describes the “hell” of combat, and the loss of “buddies.”

Don Norton

GREAT BIT OF HISTORY, I LEARN SOMETHING ABOUT WWII ALL THE TIME!

What a great story. I have read many personal accounts over the years, and this one has to be ranked as one of the best. Benz is an excellent storyteller and it is very well transcribed, as I know German and it can be difficult to translate at times.

Excellent.

Excellent read.

I enjoyed reading this very much and look forward to reading more from all sides of the war.

One thing I would like to point out is that Germans, om the losing side, complain about how bad the Americans treated them are lucky they were not Americans captured by Germans or the Japanese. Germans also claim we were unfair because of over whelming air and artillery fire despite the fact of their same advantage during the first two years enabled them to defeat their enemies. It seems Germans could dish it out and brag about it but couldn’t take it when faced with the same situation. Those Germans think we treated them bad; the Russian prisoners would have gladly traded places with them.