By Joshua Shepherd

In the early morning hours of September 10, 1914, long lines of gray-clad German infantry formed up in a steady rain that only seemed to dampen spirits. In all, some 100,000 men were preparing for a desperate nighttime assault on French positions near Vaux-Marie. Enemy artillery had been decimating their ranks for days, and revenge was in order. The men were ordered to fix bayonets and silence the French batteries with little more than cold steel.

At 2 a.m., the Germans stepped off for their objective. Drawn from the Fifth Army commanded by Prussian Crown Prince Wilhelm, the men had seen hard fighting for a month. However, nothing could have prepared them for the hellish ordeal that lay ahead.

Almost as soon as they advanced, French artillerymen spotted their movement and opened fire. A whirlwind of shells crashed into the German ranks, bowling over men by the score and leaving the track of the German columns littered with the broken and dying. Confusion reigned in the darkness as the men groped hopelessly forward. When the 38th Reserve Infantry Regiment blundered into a body of troops to their front, they opened fire, inadvertently sending a steady fire into the rear of their stalled and terrified comrades.

Leaderless men wandered in terror as entire companies evaporated. A French counterattack swept through their ranks, ushering in a scene of savage bloodletting as men shouted, struggled, and killed in the darkness. By daybreak, it was apparent that the attack had been a disaster. Thousands lay dead or dying. Not a single French gun had been silenced.

The carnage that would unfold in the fields and villages of eastern France had its roots in old grievances. Since its humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the French Republic had nursed a burning desire for revenge. The war had led to the loss of the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine, which were annexed by an ascendant German Empire. For nearly four decades Germany’s rapid industrialization and burgeoning population proved an ominous threat to France as it struggled to modernize its army.

For the French, matters only seemed to grow worse. In 1882, a unified German Empire formed the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Italy, threatening a near encirclement of France. The following decade, France sought to strengthen its hand with a mutual defense pact with Czarist Russia. The Franco-Russian Alliance ensured that in the event of conflict, Germany would face an unsustainable war on two fronts.

The precarious balance of power was maintained in Europe for the succeeding three decades. However, events of the summer of 1914 would unravel that delicate peace and plunge all of Europe into bloodletting on a mass scale. On June 28, 1914, Bosnian-Serb nationalists assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, as well as his wife Sophie, during an ill-fated diplomatic visit to Sarajevo.

The murders triggered a tragic chain of events, the July Crisis, which resulted in war. Germany, intent to keep any outbreak of hostilities isolated to the Balkans, nonetheless pledged its support to Austria-Hungary in the event of war with Russia. Armed with the so-called “Blank Check” from Germany, the Austrians issued a humiliating ultimatum to Serbia on July 25.

Hostilities became increasingly inevitable as each of Europe’s great powers, in turn, assumed a bellicose stance. Although reluctant to offer overt support to Serbia, a cautious Russia began a partial mobilization of its troops on July 25, and received French assurances of support in the event of war. Despite repeated British offers of mediation, events had spiraled entirely out of control by the end of the month. Europe crossed the Rubicon of history on July 28 as Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. A single voice in Vienna had presciently opposed the move. Hungarian Prime Minister Istvan Tisza warned that war with Serbia “would, as far as can humanly be foreseen, lead to an intervention by Russia and hence a world war.”

Tragically, events would prove him correct. Two days after the outbreak of hostilities in the Balkans, Russia began full mobilization. On July 1, Germany declared war on Russia, and, anticipating the inevitable, invaded neutral Belgium on August 3. Predictably, France declared war on Germany the same day. Much of France’s military establishment was eager to join battle, keen to clip the wings of an increasingly powerful German Empire before it was too late.

Germany’s unprovoked push into Belgium had, in fact, been considered for decades. Beginning in the 1890s, Germany’s Chief of Staff, Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen, began developing a plan to outflank France’s primary defenses on her eastern border by making a wide swing through Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. It was hoped that by quickly neutralizing France, German forces would then be in a position to confront Russia and thereby avoid a hopeless war on two fronts.

The Schlieffen Plan, which called for a massive German deployment across the Low Countries, was inherited by his successor, Helmuth von Moltke. Constrained by the realities of mobilization and logistics, Moltke was forced to greatly alter Schlieffen’s original vision, reducing the number of troops envisioned for an invasion and rejecting a move into the Netherlands, confining initial German operations to Belgium and Luxembourg.

In truth, the German States fielded a dangerously imposing force more than capable of wrecking the armies of the French Republic. While just one German field army was detailed to the country’s eastern frontiers, a full seven field armies were poised to strike for the heart of France. Drawn from the Empire’s constituent states including Prussia, Bavaria, and Saxony, Moltke fielded 51 active infantry divisions and eleven cavalry divisions; moreover, the high command dipped deep into available manpower reserves, mobilizing an additional 31 reserve infantry divisions which were assigned to the front.

Of equal importance was the German artillery, a solid mix of medium and heavy artillery including 77mm field guns and 105 and 150 mm howitzers. Germany’s complement of big guns, considered state-of-the-art in 1914, was widely considered to constitute the finest artillery train in the world.

The far right of the German line was occupied by the First Army, commanded by General Alexander von Kluck. For the crucial assignment of commanding the great hammer blow that would ultimately crush the French, Kluck seemed a suitable choice. A patrician veteran of wars with both Austria and France, Kluck was an old school Prussian soldier. He was 68 at the outset of the war, but possessed an aggressive fighting spirit that would drive himself and his men to the breaking point. For better or ill, Kluck was fond of Julius Caesar’s maxim that “In great and dangerous operations one must not think but act.”

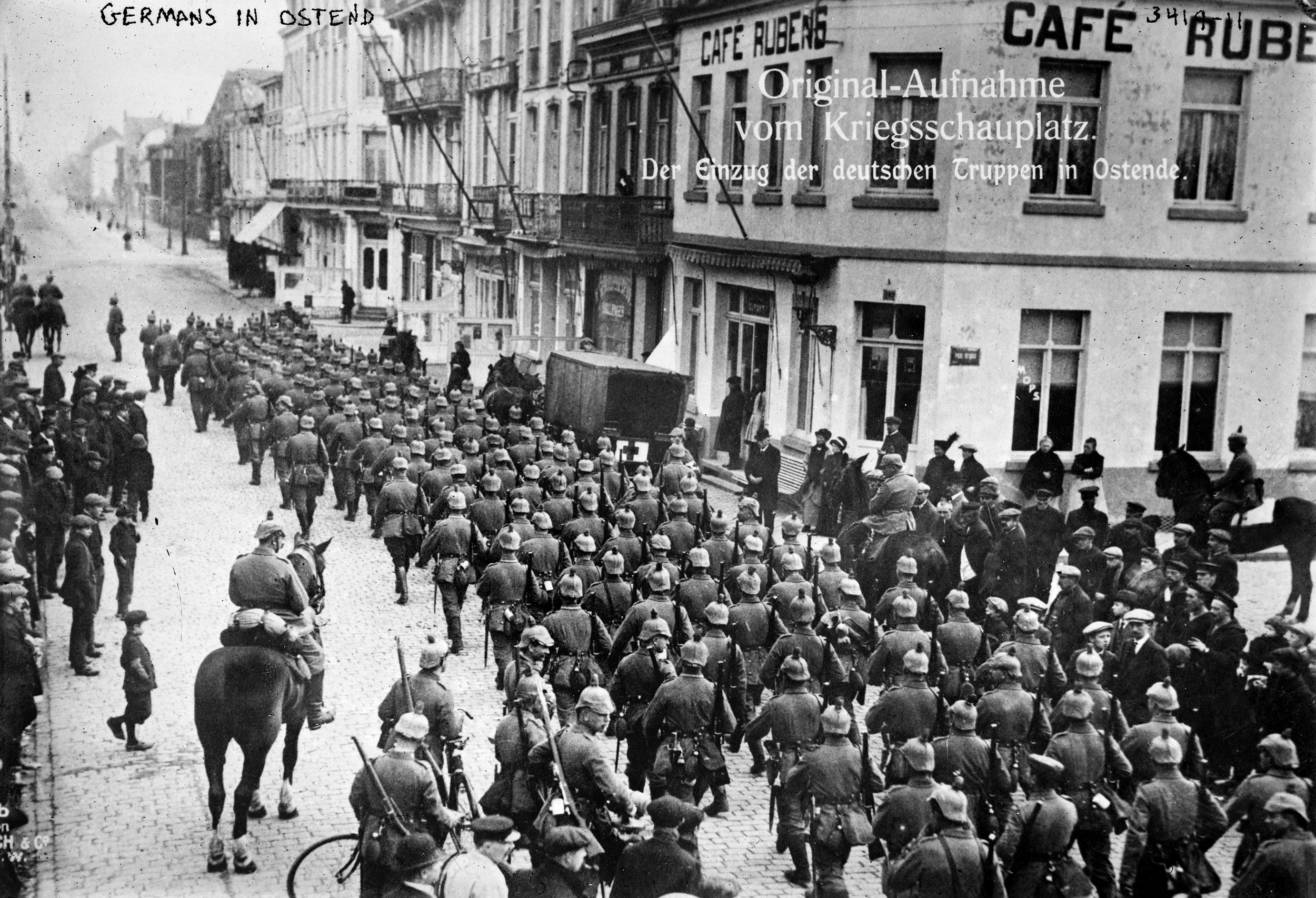

Despite the overwhelming odds, the Belgians put up unexpectedly stiff resistance when the Germans lunged across the border. German troops seized the city of Liege by August 6, but struggled to capture a string of robust fortifications ringing the city, finally reducing the defenses on August 16. The Belgian Army, badly outmatched but mounting a spirited defense of its homeland, fell back to Antwerp. By August 20, victorious German troops marched into Brussels and were poised to sweep across central Belgium and over the vulnerable French border.

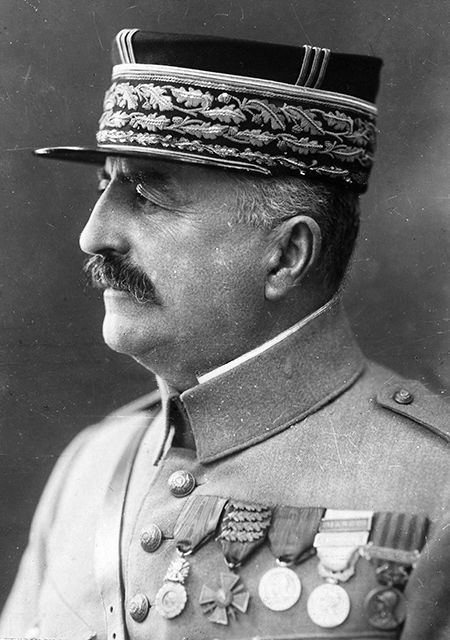

The opening weeks of the war brought little more than confusion and disappointment for the French commander-in-chief, General Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre. A career army man, Joffre had spent much of his career not as an infantry officer but as an engineer, serving in wide-ranging posts from Madagascar to Indo-China. Crucially, Joffre’s service as an engineer earned him invaluable experience on the vital military importance of rail networks.

Appointed Chief of the General Staff in 1911, Joffre sought the ouster of “defensively minded” officers who, to his thinking, had been the bane of the French Army for decades. He systematically revised field manuals and French military doctrine emphasizing tactical and operational aggression. By 1914, Joffre was 62, rather rotund, and physically past his prime. But despite appearances, the amiable Frenchman, known affectionately to his troops as “Papa Joffre,” possessed a fierce will and a burning resolution to vindicate the arms of France.

Initially convinced that any German move into Belgium would be a limited operation south of the Meuse River, Joffre unleashed his own strategic brainchild, Plan XVII, by which he sought to throw the bulk of his forces against the Germans in Alsace-Lorraine and the southern reaches of Belgium. On August 14, the French First and Second Armies pushed across the border, encountering only sporadic resistance.

For four days the French experienced surprising success as German troops obligingly fell back. The two rapidly moving French armies lost contact, unaware that they were being lured into a German trap and creating a vulnerable gap in their lines that invited counterattack.

On August 20, the Germans struck back as planned with the heavily reinforced Sixth and Seventh Armies. A general French collapse ensued, with the panicked troops of the French First and Second Armies driven back across the border with heavy losses.

Farther north, the French drive toward the Ardennes fared little better. Although intelligence reports had assured the Third and Fourth French armies that “no serious opposition need be anticipated,” they ran into disaster. Advancing into the teeth of heavy German resistance, the Third Army was badly handled and broke in confusion. The Fourth Army then received the brunt of German attentions and suffered accordingly.

After a single day of bloody fighting on August 22, the French 3rd Colonial Division, a crack outfit of experienced veterans, was badly chewed up by superior enemy forces, suffering 11,000 killed or wounded.

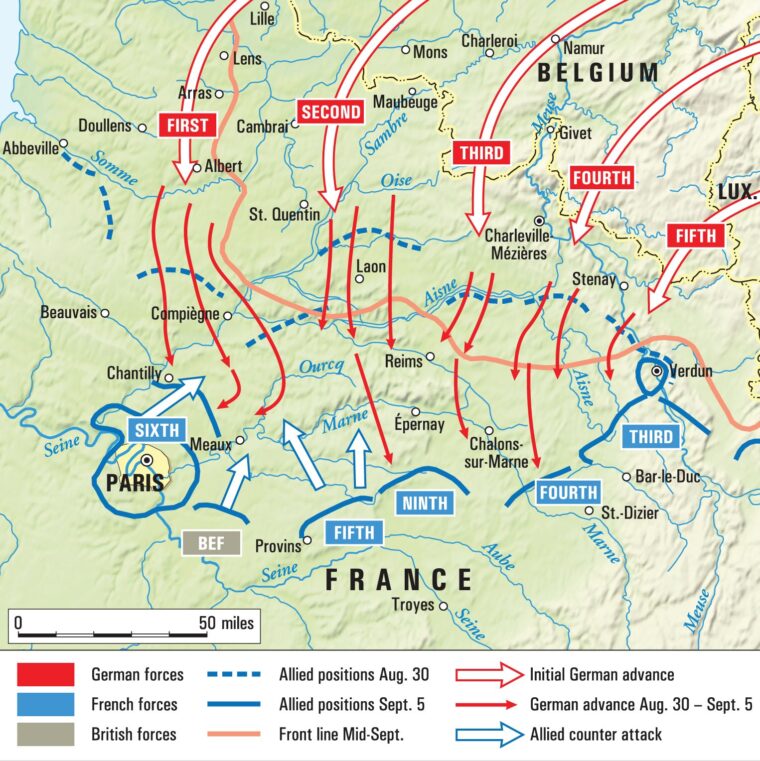

In a mere three weeks, Joffre’s ambitious Plan XVII had failed miserably, and German intentions had become increasingly apparent. No longer able to deny that the German right was moving in force across Belgium, Joffre did what he could to shift troops to counter the threat. He ordered his northernmost troops, the Fifth Army under General Charles Lanrezac, to shift north and cooperate with the BEF in an attack on the German right. But far from striking an exposed German flank, Lanrezac ran into the full force of the German Second Army; on August 21, Lanrezac’s troops were repulsed with heavy losses and driven across the Sambre River.

With the French in full flight, the task of stopping the German right flank—Kluck’s hard-driving First Army—fell to the newly arrived British Expeditionary Force under the command of Field Marshal Sir John French. Although officials in Great Britain were initially hesitant to involve the nation in any potential clash between France and Germany, the latter’s violation of Belgian neutrality proved an unavoidable provocation.

Within a mere two weeks, the nation had mobilized two corps consisting of four infantry divisions and a single cavalry division. Although small, the BEF was composed entirely of volunteers and possessed the makings of a solid fighting force. Hesitant leadership, however, would earn the BEF a reputation for painfully slow movement during the coming campaign.

The British were ordered to dig in behind the Mons-Conde Canal, hoping to stall the German juggernaut and buy time for Joffre’s shattered armies. Fighting furiously from an impressive network of trenches, the British unleashed a murderous storm of small arms fire, forcing Kluck’s advancing Germans to pay a fearful price. The BEF left the Germans stalled on the north bank of the river.

Despite the impressive British stand at Mons, Joffre was forced to face reality. In a wide arc from Belgium to Alsace-Lorraine, French lines were steadily collapsing in the face of the enormous German pincers. The greatest threat by far came from Kluck’s First Army, which was poised like a great sledgehammer to smash the Allied left. Joffre, contrary to every instinct of his aggressive nature, ordered a mass retrograde in the hope of saving his army to fight another day.

“One must face facts,” Joffre reported to the ministry of war. The French had suffered badly on the battlefield and were “therefore compelled to resort to the defensive…our objective must be to last out, trying to wear the enemy down and to resume the offensive when the time comes.”

Joffre’s mortifying decision to order a retreat would nonetheless stave off complete disaster. Over the next two weeks, the French gave ground at an alarming rate, frantically scrambling to escape the path of the German steamroller. Troops from both sides trudged 20 miles per day in blazing August heat, skirmishing as they marched.

Captain Walter Bloem of the 12th Brandenburg Grenadiers recalled that his haggard and exhausted men looked like “prehistoric savages. Their coats were covered with dust and spattered with blood from bandaging the wounded.” Undeniably, the Germans had succeeded in battering the Allied front back a staggering 190 miles. The shocking mass retrograde of demoralized French troops came to be known, fittingly, as the “Great Retreat.”

In spite of the impressive successes, cracks were beginning to show in an advancing German army notorious for a lack of communication. Adjacent army commanders could rarely directly cooperate with units on their flanks. Worse yet, Moltke was a distinctly hands-off supreme commander who ran the entire war from a rather comfortable office in occupied Luxembourg. Despite the prevalence of phone lines and aircraft, it could take a day or more for his orders to reach the front.

Joffre, however, proved to be a case study in dynamic command. The corpulent general was a storm of activity, personally inspecting his troops, spending much of his time on the telephone keeping tabs on his commanders, and even employing a French race car driver to ferry him around the front. The differing command styles of the opposing generals would have grave consequences to the outcome of the campaign.

Though neither side realized it at first, the strategic landscape was literally changing with every mile marched. The Germans’ impressive gains now meant they were struggling with badly stretched supply lines. Moreover, Moltke had pulled vitally needed manpower out of his front lines for detached service in Belgium and East Prussia.

Although such a massive retreat was repugnant to his instincts, Joffre was far from defeated. In contrast to the Germans, every mile advanced into France meant shorter supply lines and a shrinking front line for his armies. Having inadvertently gained the advantage of interior lines, Joffre intended to use them.

An opportunity for the French finally presented itself when Kluck was faced with the choice of swinging his First Army around Paris to the west or of turning east of the city. Feeling that the BEF posed no serious threat to his own right flank and eager to drive into the flank of the French Fifth Army, Kluck chose the latter. The move was approved by Moltke, who ordered his entire army to fix the French in position while General Karl von Bülow’s Second Army, supported by Kluck’s First, would smash the French Fifth Army on Joffre’s left.

Kluck’s rapidly advancing troops, however, had already pushed far ahead, and elements of the First Army began crossing the Marne River on September 3. For Moltke, a grand opportunity seemed to present itself. Kluck’s First Army would now turn south and east, crush the French flank, and roll up Joffre’s lines. Such wishful thinking, however, led Kluck and his senior officers to dismiss alarming reports of French movements to the west. For the next two days, German reconnaissance flights reported massive enemy troop concentrations off First Army’s flank. Focused on his own impending attack, Kluck ignored the warnings.

The French, in fact, had been far from idle. On the run for more than two weeks, Joffre had begun to sense an opportunity for a successful counterattack. His first move was to sack a shocking number of senior commanders, whom he had considered as lacking in aggression or determination.

In all, Joffre fired 38 of 80 divisional commanders, 10 of 25 corps commanders, and two of eight army commanders. Among the latter was Lanrezac of the hard-pressed Fifth Army, who was replaced with General Louis Franchet d’Espérey, a hard-headed corps commander who possessed the aggression Joffre was looking for.

Drawing on his experience in building and utilizing rail lines, Joffre proved a shrewd logistician. He had begun shuffling troops to the west, creating two new field armies, the Ninth and the Sixth, in the process. Under the command of General Ferdinand Foch, the Ninth was composed of the IX and XI Corps from the Fourth Army, as well as the 52nd and 60th Reserve Divisions and the 9th Cavalry Division. The new Ninth Army would operate off the right flank of the Fifth.

The new Sixth Army, composed of the VII and IV Corps drawn from the First and Third Armies, was bolstered by the 55th, 56th, 61st, and 62nd Reserve Divisions. Under the immediate command of General Michael-Joseph Maunoury, the Sixth Army was under the nominal command of General Joseph Gallieni, the military governor of Paris. Virtually under the noses of the Germans, Joffre had succeeded in creating an enormous strike force poised off of Kluck’s flank.

Gallieni, 65, was an experienced officer with the foresight to exploit an advantage and proved to be an ideal man for the job of shielding Paris. After a lengthy career across France’s colonial empire, Gallieni had been called out of retirement at the outset of the war. Installed as the military governor of Paris, he repeatedly warned that the Germans would reach the outskirts of the capital in two weeks, but was eager to pounce on their flank if the opportunity presented itself.

During the first week of September, Joffre had remarkably succeeded in bringing a preponderance of manpower to the crucial western sector of the battle lines. His plan was to launch the Sixth Army headlong into Kluck’s exposed right flank, while the BEF and the Fifth and Ninth Armies completed the destruction from the south.

In fiery orders before the grand assault, Joffre revealed a grim determination to throw back the German invasion. “Every effort must be made to attack and drive back the enemy. A soldier who can no longer advance must guard the territory already held, no matter what the cost. He must be killed where he stands rather than draw back.”

Unfortunately for the French, complete surprise proved elusive. On the morning of September 5, Maunoury’s Sixth Army began working its way east from Paris, hoping to take up positions near Meaux and smash Kluck’s flank the following morning. But German patrols reported on French movement and alerted the commander of Kluck’s flank protection, the IV Reserve Corps under the command of General Hans von Gronau.

Immediately alarmed by the reports, Gronau suspected that the French were, indeed, preparing to launch a massive flank attack. Realizing that time was off the essence, Gronau made a bold decision on his own initiative. Rather than dig in and fight a defensive battle, he impetuously launched his own understrength corps into the teeth of Maunoury’s massive Sixth Army.

Gronau pushed his infantry forward onto a wooded ridge that paralleled the Ourcq River, then opened up on the advancing French with concentrated artillery fire. After overcoming the initial shock, French troops pushed forward, but were stalled by the artillery and stubborn small arms fire. French guns returned fire and Gronau’s troops suffered heavy casualties. After taking the worst of the fight against superior numbers, Gronau decided to pull back that night. His gamble had paid off; the French had been stalled and Kluck, now alerted to the danger to his right, had been given precious hours in which to prepare.

Rather than fall back to safer positions, Kluck began shifting forces to his threatened flank. Kluck rushed his II and IV Corps to reinforce Gronau and then launch an attack across the Ourcq. It was a characteristically aggressive move on Kluck’s part, but in strengthening his right, Kluck had largely stripped his left—opening a 35-mile gap between his own left flank and Bülow’s Second Army.

On the morning of September 6, the two sides fought to a bloody stalemate west of the Ourcq River. Maunoury sent in his 55th Infantry Division, along with a brigade of Moroccan colonials, to smash into Kluck’s flank. The French attack, however, stalled in the face of well-directed artillery fire and was then stopped in its tracks by the arrival of German reinforcements.

Maunoury resumed the attack the following day, but the fighting went badly. When the French 63rd Division was hit hard with artillery followed by an infantry charge, it broke under the pressure, threatening to destabilize Maunoury’s line. The French 5th Artillery Regiment leapt into action, tearing up advancing German columns with a hail of 75mm shells.

When Kluck received sketchy reports of the BEF advancing from the south, he was alarmed by the potential threat to his open left flank. He consequently ordered the III and IV Corps, then attached to Bülow’s Second Army, to immediately reinforce his own position. But unknown to Kluck, Bülow had already ordered both corps to fall back to safer positions behind the Petit Morin River. Conflicting orders, paired with a woeful lack of coordination between German army commanders, would have fateful consequences.

From Paris, Gallieni continued to funnel all available troops to the front in an effort to stiffen Maunoury’s men as they battled it out with Kluck. Although primarily using rail lines for troop transport, Gallieni nonetheless creatively used every available means. Two infantry regiments, the 103rd and 104th, were ferried to the front aboard Paris taxi cabs requisitioned for the war effort. Transporting four or five men at a time, 1,200 Renault taxis endured traffic jams and a harrowing night journey to the front. The efforts of the taxi cab drivers, exploited by French propagandists, would become the stuff of national legend.

As fighting erupted all along the front, it became apparent to the Germans that Joffre had succeeded in marshaling forces for a grand counterattack. In a broad arc from Paris to Verdun, a front of 160 miles, artillery churned the battle lines into dense clouds of smoke and dust. The largest battle yet to unfold in Europe was about to pit 750,000 Germans against 100,000 British and 980,000 vengeful French. Contemplating the prospects of the developing battle, Moltke wrote that “A great decision will come about…should I have to give my life today to bring about victory, I would gladly do it a thousand times.”

Although Moltke would remain safely ensconced at his headquarters, his men by the thousands would indeed sacrifice their lives. Bülow’s Second Army was hit hard by d’Espérey’s Fifth Army, the German front caving in for about three miles. French troops, burning for vengeance, paid little heed to the customary rules of war. When a battalion of the German 74th Reserve Infantry Regiment was surrounded during a mad retreat, French troops ignored white flags and kept up a steady fire. When the shooting finally subsided, just 93 men were taken prisoner; 450 had been shot dead.

For Bülow, the situation only worsened. On September 8, the French 36th Division attacked northwest of Montmirail, driving in the German defenders and rendering German possession of the town untenable. With his III and IV Corps detached for service with Kluck, Bülow ordered his troops to fall back six miles and regroup. Although he temporarily relieved the pressure on his Second Army, Bülow had inadvertently widened the gap between himself and Kluck.

Farther to the east, the Germans would experience a bit of luck. After incessant hectoring from a hard-pressed Bulow, the Third Army’s General Max von Hausen decided to make a move. Realizing that the bulk of the French forces were clearly committed to crushing the German right, Hausen felt that the enemy in his front was likely weakened and ripe for a vigorous attack.

In a daring attack on September 8, he ordered his Saxon troops forward with bayonets fixed and rifles unloaded. It was a bold move reminiscent of the 19th century, and Hausen’s troops crossed the Somme River and crashed into unprepared elements of Foch’s Ninth Army, sending it reeling to the south. Foch’s retreat was littered with his dead, and his position at the Saint-Gond Marshes was left in German hands. Hausen’s Third Army had likewise paid a heavy price for its gains.

In fact, rapidly mounting casualties were beginning to shock commanders on both sides. Artillery was quickly proving itself a dominant force on the battlefield, far outstripping the infantry tactics of the previous century. Technological advances had rendered the modern battlefield a surreal scene of bloodletting on an industrial scale. The artillery of the First World War rained tons of steel from the sky, churning up vast swaths of earth and killing men wholesale. The terrifying experience of artillery bombardment cracked men’s nerves, demoralized entire units, and accounted for the majority of battlefield casualties.

As the fighting intensified, Kluck was facing a particularly thorny dilemma. German patrols had confirmed that the BEF was moving directly for the enormous gap between the First and Second Armies, but the general was reluctant to abandon his hard-won gains. Despite the fact that his army was clearly in a tight spot, Kluck, who had recently received fresh reinforcements, made plans to go on the offensive with a bold strike against Maunoury’s left flank.

For his part, Bülow was increasingly demoralized by what he perceived as Kluck’s refusal to close the gap between their respective armies. On the evening of September 8, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hentsch, a staff officer from Moltke’s headquarters, paid a visit to Bülow’s headquarters. The simple staff visit, as well as the decisions of a mid-level officer, would contribute to changing history.

Hentsch announced that he was authorized to order, if deemed necessary, a withdrawal from the Marne. From the outset, a pessimistic Hentsch seemed inclined to retreat. Bülow initially resisted such a move, but the following morning, he was rattled by fresh intelligence. Enemy troops were moving in force into the gap between the First and Second Armies. Exasperated by a continued lack of support from Kluck and painfully worried about the safety of his right flank, Bülow made the momentous decision to withdraw his forces behind the Marne.

Proceeding to First Army headquarters, Hentsch met with Kluck’s chief of staff and was further discouraged by what he witnessed. Incredibly, Kluck, who was nearby, remained unaware of the meeting. Convinced that Kluck had no chance of success in his current position, Hentsch peremptorily ordered the First Army to break contact with the enemy, retreat to the northeast, and link up with Bülow. In a matter of hours, the entire German offensive that had steamrolled across northern France had been brought to a halt by a single staff officer.

As the order was passed along the front, the common fighting men of the German armies were dumbfounded and outraged by the turn of events. After marching hundreds of miles and fighting a grinding war of attrition, most of the men were optimistic of securing a final victory and hoped to continue the attack. The men of Kluck’s First Army, in particular, had felt that their impending attack would finally break Maunoury’s army and lead to a great victory. Some men raged, others were seen to weep. General Oskar von Hutier of the Second Army’s 1st Guard Division stubbornly refused to comply; when initially given the order to retreat, he angrily snapped at his superiors, “Have they all gone crazy?”

With the Germans falling back all along the front, the Allies edged forward. On September 9, lead elements of the BEF and the French 5th Army crossed the Marne, facing little opposition. Despite the dramatic turn of events, the enormous gap in the German lines would largely, and inexplicably, remain unexploited. To Joffre’s consternation, the BEF was extraordinarily slow in moving into the breach, and simply failed to press the attack with resolution.

The two armies nonetheless clawed and badgered each other by the hour, suffering staggering casualties. Moltke made a personal visit to the front on September 11, initially meeting with Hausen at his Third Army headquarters. Despite having suffered 15,000 casualties in the previous 10 days, Hausen was adamant that he could hold his own until the lines stabilized and a new offensive could be undertaken. Moltke, buoyed by Hausen’s optimism, agreed. But when word came from Bülow that enemy forces were threatening to turn Hausen’s right flank, Moltke once again lost his nerve and ordered the general retreat to continue.

With the enemy falling back, Joffre ordered a pursuit, snatching up prisoners and supplies and regaining precious ground. By September 14, the Germans halted on high ground north of the Aisne River and dug in. Repeated French attacks resulted in bloody repulse, and both sides commenced a futile attempt to outflank their opponent. The famed Race to the Sea ensued, as both sides extended their lines to the north, ultimately anchoring the lines on the North Sea Coast.

Ultimately, the First Battle of the Marne would tragically result in a senseless four years of bloodletting on a global scale. By the time the lines had stabilized in October, a new era of modern conflict – trench warfare—had been ushered in. For the subsequent four years, the lines would remain largely static; the fighting at the Marne would constitute the last mass maneuver of armies on the Western Front. Aggressive commanders such as Joffre and Kluck, schooled in the grand tactics of the Napoleonic era, had become obsolete.

Due to the sheer number of men involved and the confused nature of the fighting along the Marne, precise casualty figures for the September 5-12 battles remain elusive. The scale of bloodletting, however, shocked the civilized world. The 160-mile-long front between Paris and Verdun was left a smoking charnel house, littered with the shocking destruction wrought by modern warfare: the vast wreckage of two great armies, thousands of dead horses, and the human slain carpeting miles of the countryside.

Estimates vary widely, but during the first half of September, it is thought that each side individually suffered 250,000 overall casualties in killed, wounded, and missing, numbers which were unimaginable before the outbreak of the war.

Despite such horrific losses, the struggle that unfolded in early September of 1914 became, for the French people, the “Miracle of the Marne.” It had, indeed, constituted a providential turning of the tide in a war that had initially seemed to auger disaster for the French. Paris had been saved, and the German drive into the heart of the French homeland had been turned back.

For the common soldiers who struggled and died at the Marne, the grand sweep of history was far removed from the grisly horrors they had faced in the killing fields of France. Penning a letter to a hometown newspaper in the aftermath of the Marne battles, an anonymous German soldier summed up the nightmarish ordeal.

“My opinion about the war has remained the same,” he wrote. “It is murder and slaughter, and it is still incomprehensible to me today that humankind in the twentieth century could commit such slaughter.”

500,000 casualties. For What?

“ On July 1, Germany declared war on Russia, and, anticipating the inevitable, invaded neutral Belgium on August 3.”

Shouldn’t that be “August 1st?”