by Robert Barr Smith

On this writer’s desk sits a small, pewter mug, dented and somewhat bat-tered. It is neatly engraved, and the lettering reads: “Wardroom H.M.S. Harrier, presented by Q.N. 20 Course June 1956. ‘Tally Ho Pounce.’”

The little mug is a souvenir of one of the endless series of tactical exercises the Royal Navy runs year in, year out. This endless and exacting practice is one of the reasons nobody knows more about, among other operations, anti-submarine warfare than the men who serve under the White Ensign. Such expertise comes of hard practice and long tradition, and it owes much to a single storied British captain, the man, many say, who had more to do with destroying Hitler’s U-boat menace than any other single officer. His name was Frederic John Walker.

Walker, inevitably called Johnny, was a professional naval officer who began his maritime education at the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, when he had just turned 14. He served at sea during the First World War, and afterward became deeply interested in a new area of naval warfare, the battle against submarines. In spite of repeated assignments to the big ships of the navy between the wars, he kept his interest in anti-submarine tactics and in 1937, as a commander, he was assigned as experimental commander at the Anti-Submarine School at Portland, where he worked on anti-submarine tactics and weaponry.

There is some indication that Walker’s uninspiring assignments between the wars produced some less-than-glowing reports by his seniors, and even that he was due for early retirement as the clouds of World War II loomed on the horizon. In view of his astonishing achievements at sea during the war, it may well be that what his seniors saw before the war was an outspoken officer bored and frustrated in a series of, to him, meaningless assignments. For once Walker came into his own at sea during the war, his record was nothing short of spectacular. He was not only promoted to captain but also awarded extra time-in-grade to make up for whatever delay in promotion his earlier reports may have cost him.

With the outbreak of World War II and the German U-boat offensive, the Royal Navy, committed all over the world, had far too few escort vessels both to protect the vital Atlantic convoys and to screen the heavy ships of the fleet. In the first three months of war, the German submarine service sank more than 400,000 tons of merchant shipping, losing only nine boats of its own. In June 1940, alone, as the Royal Navy lost more escort vessels lifting the British Expeditionary Force from the beaches of Dunkirk, the U-boats sank almost 600,000 tons more. At that rate, or anything close to it, the merchant fleet would be destroyed in time, and Britain would be starved out of the war.

Walker got his chance at last in the fall of 1941, when he was appointed to the command of the 1,200-ton Bittern-class sloop HMS Stork, and to the leadership of 36th Escort Group. Walker was a driver, as most good commanders are, and his crews and captains trained exhaustively ashore at first. His commanders learned his system of command during an attack, based on pre-arranged codes designed to catch a U-boat in the ship’s asdic (sonar) and hold it there. “Buttercup astern,” for example, told the ships of the group precisely what maneuver to execute and the direction in which to do it. With experience, Walker’s captains could almost read his mind, and operations were carried out with a minimum of terse messages between ships.

Again and again, Walker rehearsed his ships in various patterns of attack. The group would have particular success with what they called the “creeping attack,” a technique for dealing with a U-boat which had dived deep to escape the hunters. One ship, usually the senior commander on the scene, would trail the submarine by 1,500–2,000 yards, keeping contact by asdic. (the British term for sonar, asdic, is somewhat ponderously derived from Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee). A second warship would then move very slowly over the submarine without using her own asdic, directed by the first ship. On order, she would drop a preordained depth charge pattern, then go to high speed and clear the area. The directing ship would close in right behind her, dropping her own preset pattern.

The creeping attack insured that the first assault would come without warning because the enemy would not pick up the asdic of the first ship right above her. The U-boat skipper would know he was under attack only when the first depth charges exploded around him and would have no time to take evasive action.

When there were enough escorts present, the senior officer might order a variation called the “plaster attack.” In this similar technique, three escorts cruised slowly over the submarine in line abreast, directed by a fourth vessel behind them. The three then attacked together on order, the middle ship centered over the quarry. A sudden sharp turn by the submarine, either right or left, would bring the boat directly under more depth charges.

Officers and asdic operators trained on the attack trainer, a simulator that would duplicate the conditions they would encounter at sea. The all-important depth charge crews drilled with their awkward 500-pound charges ashore until they could meet Walker’s exacting standard. They had 10 seconds to reload after dropping the last round of charges, a colossal task on dry land, let alone on a pitching deck in a heavy sea. Gun crews were expected to get off six rounds within 30 seconds of acquiring the target.

Before December was out, Walker and his little ships were at sea, covering homeward-bound convoy HG76, consisting of 31 freighters and a fleet auxiliary bound for England out of Gibraltar. Besides his own Stork, Walker’s escort group included the older sloop Deptford and seven Flower-class corvettes: Marigold, Rhododendron, Convolulus, Penstemon, Gardenia, Vetch, and Samphire. In addition, for part of the way the escorts would be reinforced by three destroyers, including the ex-U.S. Navy four-stacker Stanley—and out ahead of the convoy were four more destroyers temporarily detached from Force H, based at Gibraltar.

The Royal Navy corvette deserves a mention here, for these little warships were the backbone of the convoy escorts, particularly early in the war. They carried depth charges, a single four-inch gun, a two-pounder antiaircraft cannon, when one was available, and an assortment of machine guns, some of them World War I-vintage Lewis guns. Later versions got a couple of 20mm Oerlikon antiaircraft guns as well.

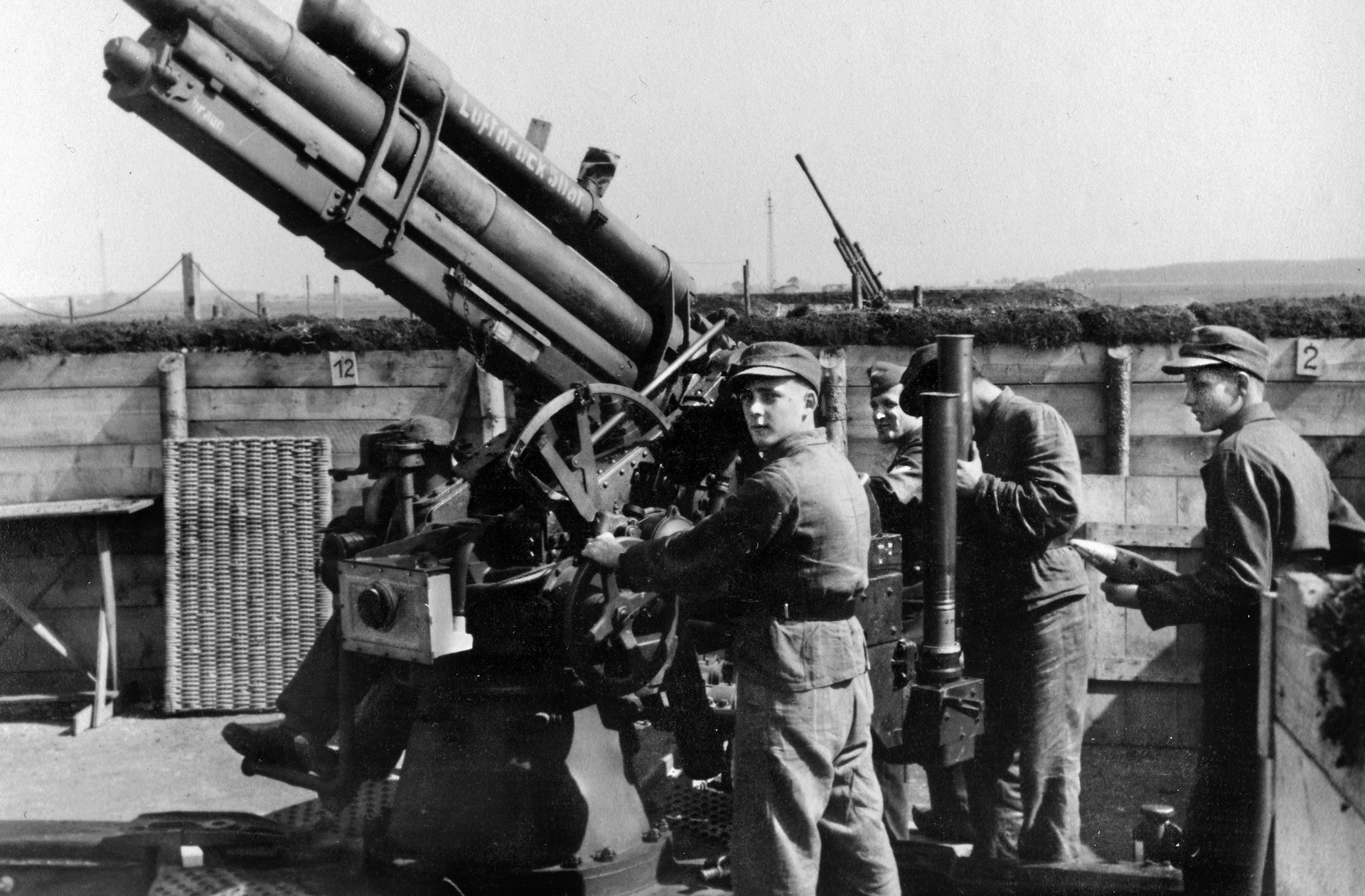

Like other escort vessels, many were later fitted with the hedgehog spigot mortar, an ingenious device developed in 1941 by the British office aptly named the Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development. The hedgehog was a simple device: a divided box filled with 24 missiles that looked like oversized rifle grenades. As the warship charged down on an asdic contact ahead, the hedgehog threw salvos of bombs filled with Torpex high explosive some 250 yards forward of the ship. They had no preset pistols to fire them as depth charges did; they would explode on contact at any depth.

The Cruel Sea Told of the Rough Life Aboard a Corvette

Originally designed as coastal escort vessels, the corvettes could manage no more than 16 knots flat out. They were tiny vessels of shallow draft and short length, and therefore given to rolling and pitching horribly in any kind of sea. They were “wet” as well, sailor’s language for any ship that took heavy seas on board when the going got rough. As with other escorts, privacy was almost nonexistent, sleep sparse and interrupted, and other comforts rare. Seizing an apparently quiet moment for a wash, Walker’s executive officer, Lieutenant J. Filleul, ran to action stations, as a newspaper told the tale, “with his shirt in one hand and his trousers in the other.”

Life aboard a corvette was especially spartan and rough. That exacting, draining duty was superbly described in Nicholas Montsarrat’s The Cruel Sea, a tale of life on the corvette Compass Rose. The little ships were quick to construct, however, and helped fill the desperate need for escort vessels. Altogether, more than 200 Flower-class corvettes were built.

In retrospect, the battle that developed around convoy HG76 would prove to be, in Winston Churchill’s words, the “end of the beginning” of the U-boats’ domination of the Atlantic trade routes. It would mark the advent of new tactics for the defenders of the convoys. The passage north past Spain and Portugal, skirting the deadly Bay of Biscay, was bound to be contested. Axis agents could watch the convoy forming up at Gibraltar, and long-range Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft out of France could shadow the convoy all the way, calling in packs of submarines as the convoy worked its way north.

The Focke-Wulf 200C Kondor was the Luftwaffe’s primary maritime reconnaissance and bombing aircraft, with a substantial range of about 2,300 miles. The Kondor carried a cannon in one top turret, a machine gun in a second, and more guns in her waist and in a peculiar cylindrical bomb bay set a little off center to starboard in her belly. During the long trip north, Walker and his captains could count on the regular presence of relays of these four-engined shadows.

Thus far, the concept of convoy protection had been, of necessity, essentially what it was in the latter days of World War I: defensive in nature, a perimeter of escorts shielding the precious merchantmen, trying to keep attacking submarines away from the relatively slow and vulnerable cargo ships and tankers. On this voyage, however, Captain Walker was to employ his own revolutionary notions of offensive protection, sending his warships ranging far out from the convoy to strike shadowing U-boats before they could engage.

And on this trip he had the invaluable support of the little escort carrier Audacity and her tiny complement of four Martlet (Grumman Wildcat) fighters. Audacity was a no-frills conversion from the captured German cargo ship Hannover, primitive by later standards, without either hanger or elevator or any substantial antiaircraft armament. The first of many Royal Navy escort carriers, she would make only three voyages before she was lost; but while she lasted she was an enormous help to the hard-pressed surface escorts. At last, a convoy in mid-ocean could have its own eyes and talons in the sky. On this trip little Audacity would conclusively prove the great value of escort carriers.

Many more would follow her, in both the Royal and the United States navies. Most of the British escort carriers were built in American shipyards and were far more sophisticated than Audacity. She was a pioneer in the anti-submarine warfare business nevertheless. Even though her fighters could not carry depth charges, they were still invaluable in spotting lurking U-boats long before they could reach attack positions; they at last gave the convoy the means to drive off or shoot down shadowing German planes. On a single voyage, Audacity’s fighters would destroy six of the Luftwaffe’s big aircraft. And even if a U-boat were not sunk after being spotted by carrier aircraft, once they or the warships of the escort drove the submarine under, she reverted to her glacial underwater speed and lost the surface speed required to quickly close with the convoy.

On December 14, the day of sailing from Gibraltar, the surface vessels drew first blood. Working some 30 miles off Cape St. Vincent at the southwest tip of Portugal, the destroyer HMAS Nestor of the Force H contingent depth-charged and sank U-127 with all hands. Walker concluded, correctly, that the Germans knew the convoy was at sea and that other U-boats would sail to intercept. There was no hurrying the progress of the convoy, a massive block of merchantmen sailing in parallel columns. The convoy could move no faster than the speed of its slowest ship while the U-boats closed in, sailing on the surface in darkness.

On the following night, a Swordfish biplane flying out of Gibraltar located still another submarine and drove it under. So far, so good, but by this time another 10 U-boats were moving to intercept HG76, and the convoy had seen a shadowing Focke-Wolf 200 Kondor. Walker and his commanders knew they were in for a fight. It began in earnest on the morning of the 17th, when his escorts charged after a submarine spotted from the air more than 20 miles from the convoy. In the ensuing action, corvette HMS Penstemon damaged U-131 and drove her under and away from the convoy.

And as U-131 crept back toward the convoy, she was spotted on the surface by Stork and three other escorts. This time the British ships were helped by a fighter from Audacity, which dove to strafe the U-boat. Hit by machine-gun fire from the submarine, the Martlet crashed, but the guns of Walker’s escorts, shooting at the extreme range of seven miles, hit U-131 eight times. The U-boat’s captain called it quits, opened his boat’s sea-cocks, and got most of his crew off. The British ships picked up the body of the Martlet’s pilot and 55 survivors from the U-boat.

The following night, the 18th, would be the ultimate test of Walker’s theories: a close-in protective escort group stayed close to the merchantmen, while Walker’s hunters ranged far out from the convoy. Again the hunter-killer group detected a shadowing U-boat, and Exmoor, Stanley, Blankney, and Deptford blasted U-434 to the surface. The British collected her captain, Korvetten-Kapitaen Heyda, and his entire crew but two before U-434 went down for the last time.

“Either You Leave the Boat or I do. I Take no Further Responsibility.”

Later in the next afternoon, however, Walker’s ships suffered their first loss. U-574 torpedoed HMS Stanley, which blew up, a monstrous flash of flame ripping through the gloom hundreds of feet high. There were few survivors. Stork and her consorts went after the killer and got their revenge less than an hour later, closing in to hammer the submarine with precise depth-charge attacks. As damage mounted in the submarine, the captain and his engineering officer, responsible for the trim of the boat, argued bitterly over whether to surrender. Finally the engineer settled the matter. “Either you leave the boat or I do. I take no further responsibility.”

Leaking, her electric motors out of action, an electric fire flickering in her control room, the submarine blew her tanks and surfaced. Walker in Stork charged down on U-574, chasing his quarry in a series of concentric circles, each vessel trying to turn inside the other. When Stork got too close to the U-boat for the sloop’s main guns to bear, Walker at last rammed the U-boat, shoving U-574 onto her side. As Stork ground on across the submarine’s hull, Walker dropped a 10-round salvo of depth charges on shallow setting and the submarine was finished. Walker’s ships fished 28 British and 18 German survivors from the water; they did not include either the U-boat’s captain or his engineering officer. Walker commented later: “I was surprised to find later by the plot that Stork had turned three complete circles … I kept the U-boat illuminated with ‘Snowflakes’ which were quite invaluable in this unusual action … some rounds of four-inch were fired from the forward mountings until the guns could not be sufficiently depressed, after which the guns’ crews were reduced to shaking fists and roaring curses at an enemy who several times seemed to be a matter of a few feet away rather than yards….”

Meanwhile, a merchantman, SS Annavore, had been torpedoed, and more Focke-Wulfs had appeared. Audacity’s Martlets would shoot down four of the Kondors in spite of the big planes’ four defensive turrets. One fighter pilot, Sub-Lieutenant J.W. Sleigh, pressed his head-on attack so closely that he grazed the falling Kondor and returned to Audacity with part of the German’s radio antenna wire wrapped around the tail of his Martlet.

But more U-boats of the gathering pack still remained around the convoy, and Walker was left with only four ships after some of his escorts ran low on fuel and had to turn for home. One of Audacity’s fighters jumped two U-boats stopped side by side, one with a hole visible in its hull. A plank had been laid down as a gangway between the two, and crewmen were crossing it. The Martlet pilot attacked with machine guns, his only weapon, raking both boats and shooting men off the plank.

Both U-boats dived and disappeared, but four more submarines were sighted, and Walker correctly concluded, “The net of U-boats round us seemed at this stage to be growing uncomfortably close in spite of Audacity’s heroic efforts to keep them at arm’s length.

Stork herself was now limited to only about 10 knots, for the ramming of U-574 had damaged her bow and torn away the dome that shielded her asdic. At about 10 o’clock on the night of the 21st, a Norwegian merchantman was torpedoed. Worse was to come, for just then the other merchantmen, following standing orders, fired “snowflake” flares, designed to expose a U-boat working close to the convoy or within its columns. In this case, however, exposed by the glare of the snowflakes, Audacity was hit a few minutes later by three torpedoes from U-751. She sank quickly, and her survivors were picked up by the escorts, which continued to harry the shadowing U-boats.

And on the 21st, the group scored again: depth charges from HMS Deptford caught U-567 and sank her without a trace. Her skipper, who died with her and her whole crew, was the famous Kapitaenleutenant Engelbert Endrass, one of the Kriegsmarine’s few remaining ace skippers. A second boat, U-67, also took a terrible pounding from 41 depth charges from Rhododendron and Deptford.

The next night, Walker ordered three changes of course by the convoy and staged a mock battle to lure the shadowing enemy away from the convoy’s new courses. The deception worked and, on the 23rd, now covered by Coastal Command aircraft and a couple of fresh destroyers, the convoy made port. Walker was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his victory and had the deep satisfaction of knowing that his tactics had worked. The Merchant Navy knew it too, and the commodore of the convoy signaled Walker: “On behalf of the convoy deepest congratulations and many thanks.”

During the last of the fighting on this run, Walker showed his understanding of the terrible pressures under which his men, especially his captains, worked constantly. During the night Deptford, hot on the trail of a suspected submarine, went in to ram and found her target was not a U-boat, but Stork. Adroit ship handling minimized the collision, but the damage was still considerable. Walker did not reprimand his captain and showed his own sense of humor when another ship signaled him at daylight. “What have they done to your nose?” It was an allusion to the bow damaged in ramming U-574, and Walker replied, “That’s nothing. You should see what they have done to my arse.”

Not only were his escorts sinking U-boats, but his wide-ranging hunters made it much harder for a U-boat to run on the surface, even at night. Since sailing submerged vastly reduced the speed at which a submarine could close the convoy, Walker’s boldness kept many U-boats out beyond torpedo range. On at least two occasions during the war, his ships sank enemy boats as far as 40 miles from the convoy Walker was covering. Although anything approaching total victory over the Kriegsmarine was still many dreary months away, this battle was at least a draw for the convoy escorts and maybe something of a victory.

Attack Always; Never Let the Enemy Pause to Take a Breath; Whatever the Odds, Attack.

Johnny Walker was a deeply religious, genial man with a quiet sense of humor, but he was also a demanding leader who left no doubt as to who was in command. Nor did his operating instructions leave any question about the purpose of his tactics: “Our object is to kill, and all officers must fully develop the spirit of vicious offensive. No matter how many convoys we may shepherd through in safety, we shall have failed unless we slaughter U-boats. All energies must be bent to this end.”

Walker was the embodiment of the Royal Navy’s aggressive philosophy: attack always; never let the enemy pause to take a breath; whatever the odds, attack. One of his officers summed up Walker’s character: “[H]e showed me the type of person it takes to win wars, he was absolutely dedicated to seeking and destroying U-boats. He spent most of the time on the bridge walking up and down, he had a special coir mat provided to deaden any sound he made so that he could hear the asdic … He slept very little, sometimes only two hours a night….”

Walker took only a few days leave and hurried back to duty. Throughout his meteoric career in World War II, this dedicated, driven officer pushed himself far beyond any reasonable physical boundaries. Returning quickly to 36th Group, he sailed temporarily in the sloop HMS Pelican, later shifting back to Stork after dockyard repair of the damage caused when she rammed U-574. The 36th Group got another three, and maybe four, more submarines before an unwise Admiralty assigned Walker to a shore job in Liverpool.

Walker was not at all happy sailing a desk and steadily bombarded his seniors with repeated requests to return to sea. Walker knew where he belonged, out along the far-flung convoy routes hunting the German enemy. The Battle of the Atlantic was fast approaching crisis proportions. The Allies were losing merchant ships faster than they could be replaced, and the Royal Navy had fewer than half the escort vessels it estimated it needed to keep the supply lines to Britain open and functioning.

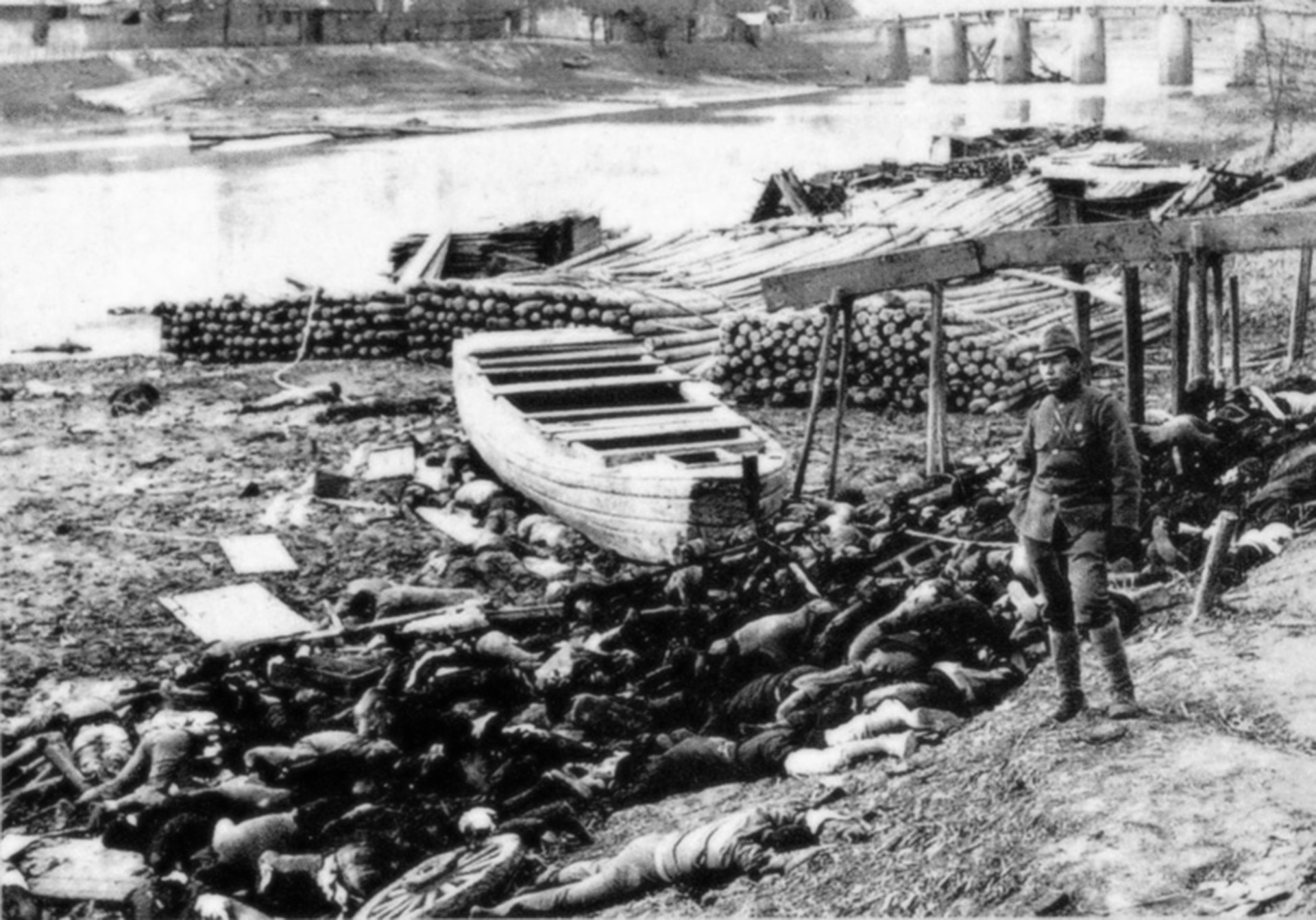

The magnitude of the commerce war is mind-boggling. The U-boats sent some 15 million tons of Allied shipping to the bottom during the war. The cost to the Kriegsmarine was 781 boats. In the course of the war, almost 30,000 U-boat personnel went down with their boats, a loss of about 75 percent of all of Germany’s submariners.

At last, in February 1943, the Admiralty relented, and Walker became captain of HMS Starling, a modern Glasgow-built sloop. Walker asked for as many as possible of his old crew from Stork, and he got almost half of them. He then took command of a new organization called 2nd Support Group, at first two sloops and seven little Flower-class corvettes, and took his new pack of hunters to sea.

Walker’s greatest success came after he persuaded Sir Max Horton, commander-in-chief of the Western Approaches, that the most efficient sub-killing machine would be a special hunting group of six first-line sloops. They would carry the most modern equipment and weaponry and operate with a roving commission, without responsibility for close-in protection of any convoy. Impressed by Walker’s record thus far, Admiral Horton agreed, and Walker got his wish. By the end of the third week in May 1943, he was at sea with his own sloop, HMS Starling, and her sister ships Wild Goose, Wren, Woodpecker, Cygnet, and Kite. Under his command, 2nd Support Group would become the most successful U-boat hunters of either world war, the model for every anti-submarine operation to follow.

All of Walker’s little ships were modified Black Swan-class sloops. They were 283 feet long, displacing either 1,300 or 1,350 tons (Woodpecker, Wren, and Wild Goose were a little smaller than their sisters). They could do between 19 and 20 knots, a bit faster than the original Black Swans, their sisters in the convoy escort business. While the sloops could not muster the speed of a fleet destroyer, their engines were much more efficient, giving them tremendous endurance at sea. If their top speed was only about half that of a destroyer, they could hold that speed on about a tenth of the destroyer’s horsepower, at an enormous saving in fuel. They mounted three turrets, each with a pair of four-inch guns, plus six double-mounts of 20mm antiaircraft guns. Equipped with asdic and radar, they carried a large load of depth charges and hedgehogs.

As he had with his previous group, Walker made certain his captains knew precisely what the group’s mission was. As one officer put it later, Walker told them, “Our sole job was to sink U-boats … and there followed a short list of evolutions that we had got to be able to do very quickly and accurately at any time of the day or night, in any weather, and in which no sort of excuse for failure would be accepted….”

Walker also lectured “in praise of the ram as a weapon of precision,” and laid out a few rules for depth-charge attacks. Walker’s whole emphasis was on simplicity and precision of technique and brevity of orders.

In June 1943, veteran submarine captain Gunter Poser made the mistake of sending a long radio message back to Germany within range of Walker’s radio direction-finding equipment. Poser’s boat, U-202, was returning from her ninth operational mission, coming back from dropping five German spies on Long Island. The 2nd Group homed in on the German’s signal, and Poser dived when he saw the sloops charging down on him. By that time, however, Starling’s asdic had picked up U-202 and the hunt was on, Walker directing it from a specially built platform on his bridge, wearing white shorts and a cricket shirt.

The first depth-charge attack, 86 charges, drove U-202 far under, and Poser kept on going, getting his groaning boat down as far as 800 feet. British asdic operators on the surface could hear the rush of high-pressure air on the U-boat as she corrected her trim after British attacks. At that depth her hull was close to rupturing, but at least he was safe from the British depth charges, which could not be rigged to fire as deep as Poser had gone. Walker drew the right conclusions. “No doubt about it. She’s gone deeper than I thought possible….” He smiled: “Well, long wait ahead. Let’s have some sandwiches sent up. We will sit it out. I estimate this chap will surface at midnight. Either his air or batteries will give out by then.”

As the Crew Abandoned Ship, Poser Turned His Own Pistol on Himself

And so it was. At just about midnight Poser’s air was nearly exhausted and he ordered his boat to the surface. As she broke water, her gun crews ran to man their weapons, and Poser went to full speed, hoping to run from the waiting sloops in the darkness. Walker was ready, however, and gave the order to fire star shell, tearing the cloak of blackness from his quarry. All six sloops pounded U-202 with shellfire, and a crimson gleam behind the conning tower announced a hit from one of the four-inch guns. Starling charged down on the damaged U-boat, intending to ram. As she got closer, however, Walker could see that the submarine was too battered to submerge, and so he swung his sloop and ran down the side of Poser’s boat, sluiced its decks with machine-gun fire, and dropped a pattern of shallow set depth charges.

It was over for U-202 and Kapitaen-Leutnant Poser. Poser shouted to his men to abandon ship, but he did not join them. He turned his own pistol on himself and stayed with his boat on her trip to the bottom. The hunt had taken 16 hours, and for another 14 hours Starling’s doctor, Surgeon-Lieutenant Fraser, operated on badly wounded German U-boat crewmen.

On the same trip, Walker’s group got two more U-boats, U-449 and tanker-boat U-119. A depth-charge pattern forced U-119 to surface in the midst of a ring of British escorts, all the ships banging away and shells whistling in all directions as the submarine began to dive again. Starling was on her before she could clear the surface and smashed into U-119, rolling her over and grinding across her hull. As Starling cleared the submarine, she fired a shallow pattern of depth charges and U-119 was gone, leaving only debris, including body parts.

Walker now transferred to Wild Goose, leaving Commander Wemyss of Wild Goose to take crippled Starling home. In July, the group was back at sea, hunting the 150 submarines Admiral Karl Dönitz had sent against the Atlantic convoys. Increasingly, long-range RAF and USAAF aircraft and Royal Navy surface vessels hunted together on the routes from German Biscay bases to the Atlantic. The Kreigsmarine was heavily arming its boats with antiaircraft weapons and sending them across the bay on the surface in groups. When Allied aircraft could not penetrate the antiaircraft and attack, they called for surface vessels and circled, waiting for help. If the U-boats dived, the aircraft could close in once the antiaircraft weapons were no longer manned. If the U-boats successfully submerged, the aircraft marked the spot for the surface vessels.

On the 29th, a British aircraft reported three U-boats on the surface, and the group steamed hard down the bearing the aircraft had given. Soon they had visual contact, and, according to legend, Walker could not resist hoisting the signal for “General Chase.” The story goes that this signal had been flown only twice before in the long history of the Royal Navy, by Sir Francis Drake when he pursued the Spanish Armada down the English Channel in 1688, and by Lord Horatio Nelson when he smashed the French Navy at Trafalgar in 1805.

One U-boat was depth-charged and sunk by a Royal Australian Air Force Sunderland flying boat. Other aircraft, including an American B-24 Liberator, joined the attack, and an RAF Halifax bomber mortally wounded a second submarine. Standing on his bridge as the surface ships closed in, Walker waved his hat, cheering on his Starling. She and her sisters opened fire at four miles, and their gunnery was superb. The U-boat dived, but Walker’s group closed in with depth charges and sank her. The success was part of a spectacular run of victories over the U-boats in the Bay of Biscay, nine boats sighted and seven of them sunk in just a few days.

Walker and his group returned to Liverpool in high spirits. In port, however, bad news waited for Walker. His son, Sub-Lieutenant John Timothy Ryder Walker, had been lost with his submarine in the Mediterranean. Walker’s wife Eileen was waiting to see him in this moment of agony, and the story goes that Walker’s officers formed a defensive line, for a time keeping the couple sequestered from all sorts of people who had urgent business with Walker. Always concerned with those he commanded, however, Captain and Mrs. Walker insisted on attending, the very next night, a wardroom dinner with Walker’s officers and their wives.

From this time on, Walker became even more than the professional naval officer fighting his country’s enemies; now he had a personal score to settle as well. Back at sea, he and his group hammered the U-boats stalking the merchantmen of the vital convoys. One of them, U-264, fired a “Gnat” homing torpedo at Starling, but a sharp-eyed British lookout saw the track of the Gnat as it raced toward the sound of the sloop’s screws. Walker ordered a hard turn to port, and then, as the Gnat closed in, Starling dropped a shallow set pattern of depth charges. The roar of the exploding charges was immediately followed by a second roar as the shock of the charges detonated the torpedo before it reach Starling. Walker immediately ordered a plaster attack on U-264, and within five minutes the group was rewarded by a gigantic air bubble and a litter of floating debris, including human body parts.

This voyage ended in another triumphal entry into Liverpool harbor, for U-264 was only the first of a record six submarines sunk by the group in just two weeks. The group entered harbor in line-ahead, Starling leading, her PA system playing the group’s theme song, A-hunting We Will Go, Admiral Horton and the First Lord of the Admiralty, standing on a destroyer’s bridge, met the group as they entered harbor, and the docks were lined with cheering civilians, sailors and WRENs.

An officer serving under Walker in the sloop HMS Wren wrote much later of his admiration for Walker’s leadership. On one occasion, chasing down a U-boat sighted by an aircraft, Walker’s ships had 60 miles to go to reach the scene. “In the three hours we took to get there the U-Boat, submerged, could have gone up to 18 miles in any direction, he worked out where the U-Boat captain would go and headed for it … and his calculations were spot on … [h]e dropped a pattern of depth charges and the U-Boat surfaced in his wake … all of us opened fire … Walker then decided to ram, which he did, turning the U-Boat over and dropping a shallow pattern as he went over it.”

By the autumn of 1943, it had become apparent to Dönitz and his staff that the U-boat offensive had misfired. Out of 2,468 merchantmen crossing the Atlantic, the Germans had sunk only nine, and Allied surface ships and aircraft had destroyed 25 U-boats in the same period. The Germans were losing the convoy war, but their most implacable opponent, Johnny Walker, was wearing out.

“Cease Firing. Gosh, What a Lovely Battle”

In March 1944, the group sailed to cover a large convoy traveling the terrible northern route to Russia. Among the ships in convoy was USS Milwaukee, sent as a gift to the Russian navy. The Group sank two more U-boats during the voyage, and Milwaukee made Murmansk safely. On May 5, on the way back and carrying the American crew of Milwaukee, the convoy heard that the American destroyer Donnell had been torpedoed and sunk some 200 miles away. Walker turned his group toward the site of the sinking, and two days later made contact. For 15 and a half hours, Walker stalked U-473 over 20 miles of rough sea, his ships dodging Gnats fired by their quarry. And then as U-473 ran out of air and was forced to surface, his sloops tore her apart with gunfire and sent her down. Walker briefly signaled his ships, “Cease firing. Gosh, what a lovely battle,” and turned his command for Liverpool.

It had been another highly successful voyage, but on top of all the other months of exhaustion, lack of sleep, and the crushing cares of command, the war at sea was destroying Johnny Walker. His wife was horrified by his haggard appearance. By rights her husband should have been sent ashore for a real rest, perhaps even hospitalized. But duty is a jealous goddess, and Walker knew that he had never been more needed than he was as the summer of 1944 approached. In May 1944, just five merchantmen had been sunk by U-boats. The Germans had lost 22 boats, and Dönitz had pulled most of his remaining vessels out of the north Atlantic. The Allies were plainly winning the convoy war, but there was a huge and urgent job waiting closer to home.

For the long-awaited invasion of Festung Europa was imminent, and the Navy knew its success hinged on keeping open the sea lanes across the Channel. If the U-boat fleet could interdict that steady stream of reinforcements and supplies, a lot of good men would die for nothing, and the liberation of Europe would be long delayed. And the Navy knew the Germans would come; Dönitz would throw every boat he had into the effort to cut the invasion forces off from their base in England. The supreme commander, General Dwight Eisenhower, said flatly that he had to have two weeks of absolute control of cross-Channel traffic if the invasion was to have any real chance of success. In the event, on June 6, the Germans would send 76 U-boats from Biscay ports against the Normandy landings.

Walker knew where his duty lay, and tired as he was, he saw the invasion as a double opportunity. “Eisenhower wants two weeks,” he said. “He’ll not only get it, but this is our chance to smash the U-boats for all time.” And so, on June 6, 1944, when the invasion armada loomed out of the predawn darkness off the Normandy beaches, Walker was there. This time he controlled no fewer than 40 ships. In the first three crucial days of the invasion, his flotilla put in at least 36 attacks on U-boat contacts. His ships sank eight submarines and damaged a number of others. Allied aircraft got another six, and the Germans pulled their surviving boats back to regroup.

But they came again, as the Navy knew they would, into a weeklong non-stop melee between Allied surface vessels and aircraft above, and the enemy below. Walker and his captains and the rest of the antisubmarine forces won that brawl, but it was the last straw for Walker’s health. When Starling put into a British port to rearm and refuel, exhausted crew members caught at least a few hours of sleep, but Walker could not. He used the time to plan and reorganize and attend meetings ashore. Then it was back into the fray again, and again without rest.

In the end, the U-boats of the Kriegsmarine took such a battering that they were never again the formidable threat they had once been. But this last effort also killed their most dangerous and unforgiving enemy. For Walker was plainly ill and getting worse. His face and body were skeletal, and his officers noticed that he hesitated trying to find words for a signal or an order. Now, however, he could at last spend a little time at home and perhaps give his wasted, exhausted body a chance to mend.

There was much to rejoice at for the Walkers. Not only had Walker won his long battle, but he was to be made a Knight Commander of the Bath by King George VI, he had won a total of four DSOs, and he was slated for promotion to admiral rank. The afternoon after Walker at last came home, he and his wife went to see the film Madame Curie. Afterward, Walker told his wife that he did not feel well. He was dizzy, he said, and had a sort of humming sound in his head. He grew quickly worse and worse, and at last was hospitalized. At first the doctors were confident. It was, they told his wife, only a matter of his terrible exhaustion. Rest should do the trick.

But it wouldn’t. About midnight on July 9, 1944, Johnny Walker died. The medics called the cause cerebral thrombosis, but it was generally believed that Walker had given his country and his Navy all he had for far too long. He had simply died of exhaustion, or, some might say, of dedication.

The 2nd Escort Support Group would continue to serve, now under the capable leadership of Commander D.E.G. Wemyss, who had been Walker’s executive and right arm. Before the war was finally history, the Group sank at least 23 U-boats, perhaps more, and certainly damaged many others. Starling herself was in on the kill of 14 German submarines, a record unmatched by any other single ship of any nation in any war.

Today a statue of Johnny Walker stands on the Pier Head, Liverpool. He is looking out across the River Mersey, and displayed on the far bank is one of his old enemies, U-534. After his funeral in Liverpool Cathedral, the remains of the man himself were placed on board HMS Hesperus and buried at sea, the sea he loved and defended. What he did abides, however, a permanent monument to courage and devotion.

Speaking at Walker’s funeral, Sir Max Horton, his old boss, perfectly described Walker’s legacy to the Royal Navy, to the Merchant Navy, and to the people of Britain: “In the days when the waters had well nigh overwhelmed us, our brother, apprehending the creative power in man, set himself to conquer the malice of the enemy. In our hour of need he was a doughty protector of them that sailed the seas in our behalf. His heart and mind extended and expanded to the utmost tiring of his body, even unto death; that he might discover and operate the means for saving our ships from the treacherous foes.”

But the tribute Walker would have liked best came from one of his ship’s company. When Loch Killin blew a U-boat to the surface and captured her entire crew, a watching Starling sailor exclaimed, “I bet the Old Man’s rubbing his hands up there.”

He probably was.

Author Robert Barr Smith is a retired U.S. Army colonel and a professor of law at the University of Oklahoma Law Center in Norman.

What an outstanding story and write-up. I saw a brief mention of Captain Walker in a video and was intrigued, but couldn’t find a good video on him. Instead, I looked for a site that might have some information, and yours came up. I really appreciate the detail of this story, and it gave me the answer as to why Walker is considered the father of anti-submarine tactics. Thank you for this article.