By Richard Beranty

K Rations remain one of the great icons of World War II. Soldiers either loved them or hated them. Often overused because of convenience but regarded in high esteem by those who needed them, they left a lasting impression on the men who consumed them.

During its six years of production, millions upon millions of K Rations churned out by an array of American companies under U.S. government contract. Designed as a lightweight ration that airborne troops could carry in their pockets, they provided a nutritionally balanced meal with enough calories to keep a soldier functioning for several days in the field when all other food sources were cut off. It also gave GIs a taste of home in the form of candy, chewing gum, and cigarettes.

The Field Rations From A to D

Some five years before America entered World War II, the War Department tasked the Army’s Quartermaster Corps and its newly formed Subsistence Research and Development Laboratory (SR&DL) located in Chicago to categorize field rations and develop new ones to replace the obsolete Reserve Ration in use since the end of World War I. An alphabetic system was designed to identify rations based on use.

Field Ration A, typically served in dining halls or aboard ships, provided at least 70 percent of the freshest meat and produce available. Field Ration B, mostly served in field kitchens, substituted canned foods when fresh goods or refrigeration were not available.

Field Ration C, or combat rations, was developed in the late 1930s and consisted of small cans of ready-to-eat meat and bread products. Its first major procurement of 1.5 million rations was made in August 1941, and over the next 40 years the “C Rat” evolved many times in variety, quality, and packaging, becoming the longest lived compact field ration in U.S. military history. It gave fighting men a well-balanced meal and did not spoil. Drawbacks were its bulkiness and weight. It was discontinued in 1981 with the advent of the Meal, Ready to Eat (MRE).

Field Ration D or emergency ration was an ersatz chocolate bar designed to give soldiers enough energy “to last a day.” Proposed in 1932 for the cavalry, developed in 1935, and first produced in large numbers in 1941, the D Ration was not your everyday Hershey bar. Comprising bitter chocolate, sugar, oat flour, cacao fat, skim milk powder, and artificial flavoring, the D Ration could withstand temperatures of 120 degrees without melting. GIs found it untasty and difficult to eat. In fact, package directions advise that it be eaten slowly “in about a half hour” or dissolved by crumbling into a cup of boiling water. Quartermaster records show 600,000 D Rations were procured in 1941 and nearly 1.2 million in 1942. With so many on hand, none were procured in 1943, but the following year some 52 million were ordered. By 1945, the Quartermaster General was wondering how to get rid of the vast stockpile of D Rations.

The “K” in K Rations Stood for Ancel Keys

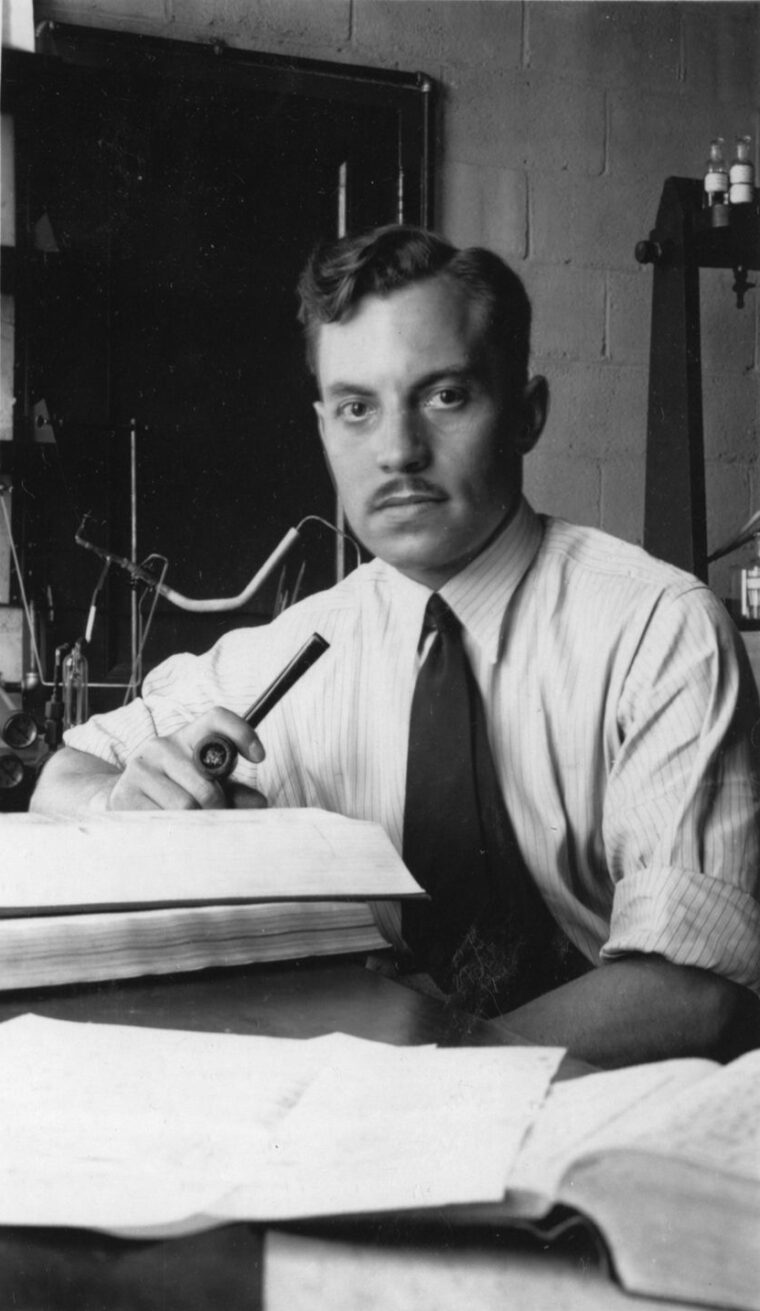

With two distinctly different field rations being readied for mass production—Rations C and D—and war seemingly imminent, the War Department recognized the need for a nutritious, nonperishable, and, most importantly, easy to carry ration that could be used in assault operations by Army airborne troops. Again it turned to the SR&DL, which enlisted the help of a relatively unknown physiologist named Ancel Keys of the University of Minnesota. Dr. Keys’s most notable study up to that time had taken place a few years earlier in the Andes Mountains of South America where he examined the body’s ability to function at high altitudes.

“I suppose someone in the War Department had the crazy idea that because I had done research at high altitude I was therefore qualified to design a food ration to be eaten by soldiers who had been briefly a few meters above the ground,” Keys wrote later.

Colonel Rohland Isker, commander of the Subsistence Lab, was the man who approached Keys for help. In 1941, the two visited a Minneapolis grocery store and purchased 30 servings of hard biscuits, dried sausage, chocolate bars, and hard candy. Picked to test the new ration was a platoon of soldiers at nearby Fort Snelling. Though the soldiers consumed the food “without relish,” according to Keys, it was given a second trial run at Fort Benning, Georgia, then home to the Army’s paratrooper school. With comfort items such as gum, cigarettes, matches, and toilet paper added, the airborne troops gave it a thumbs up and the War Department followed suit.

In May 1942, the Army placed an order with the Wrigley Chewing Gum Co. to package one million rations. Officially named U.S. Army Field Ration K in honor of Keys, the Army had found its answer for a ration that provided “the greatest variety of nutritionally balanced components within the smallest space.”

A Simple Three-Meal System

The concept behind K Rations was simple: a daily ration of three meals—breakfast, dinner, and supper—that gives each soldier approximately 9,000 calories with 100 grams of protein. Within months, scores of food, cereal, candy, coffee, tobacco, and other companies were producing components for and packaging K Rations.

If the concept was simple, so were the components. The breakfast unit contained a four-ounce can of chopped ham and egg with opening key, four K-1 biscuits, or energy crackers, four K-2 compressed graham crackers, a two-ounce fruit bar, one packet of water-soluble coffee, three sugar tablets, four cigarettes, and one piece of gum.

The dinner unit contained the same, except pasteurized process American cheese replaced the meat component, dextrose tablets replaced the fruit bar, and lemon juice powder replaced the coffee.

The supper unit differed with a can of beef and pork loaf, a two-ounce D Ration instead of dextrose tablets, and a packet of bouillon powder in place of lemon juice powder.

All items fit snugly into an inner box just under seven inches long surrounded by an outer box. The meat component and cigarettes were packed separately with the remaining items sealed in a laminated cellophane bag. A day’s ration of three units weighed just over two pounds.

“The World’s Best-Fed Army”

The ration was much ballyhooed by the War Department at the time in posters and magazine advertisements through its Office of War Information. Army Signal Corps publicity photos show each item and describe its purpose: meat and cheese canned products for protein; K-1 biscuits for starches, carbohydrates, and minerals; K-2 graham crackers for roughage, vitamins, and starches; fruit bar for energy and vitamins; D Ration, sugar, and dextrose for energy; lemon juice powder for vitamins and minerals; bouillon powder for protein; cigarettes for a satisfying smoke; and chewing gum for thirst and tension.

The reverse side of these photos, which are dated December 30, 1942, reads as follows: “Now going into large scale production after rigid, scientific tests in the field, the U.S. Army’s Field Ration ‘K’ is playing a vital part in helping to keep the ‘world’s best-fed army’ well fed the world over even under combat conditions. The ration unit consists of three packaged meals—breakfast, dinner, and supper—each one containing a well balanced variety of appetizing, nourishing foods. Chewing gum is included to conserve water and relieve nervous tension. Specially concentrated foods furnish the necessary vitamins, proteins, minerals and carbohydrates.”

Research to improve the ration continued over the next months and years. Chocolates and hard candy replaced the dextrose tablets, D Rations, and fruit bars. A compressed cereal bar and orange juice powder were added to the breakfast unit, matches to the dinner unit, and toilet paper to the supper unit. The meat component evolved too. Late-war supper units featured corned pork loaf with carrots and apple flakes. To protect the cigarettes from being bent during shipment and storage, a thin cardboard sleeve was added to surround the meat component.

The companies that produced these products and their brands reads like a Who’s Who of corporate America. Some examples include H.J. Heinz and Republic Foods—meat component; Peter Paul’s and Charms—candy; Nescafe—coffee; Miles Laboratories—lemon juice powder; Jack Frost—sugar tablets; Beeman’s, Wrigley’s, and Dentyne—gum; Camel, Chesterfield, Philip Morris, Fleetwoods, and Marvels—cigarettes.

K Ration packaging evolved as well during the war. Early-war outer cartons contained only the meal title and packager’s name, such as Wrigley, Heinz, The Cracker Jack Co., American Chicle, Hills Bros., General Foods, Kellogg’s, even whisky maker Hiram Walker and Sons. Mid-war cartons added the menu and some directions concerning food preparation. Late-war rations differed the most in that the brown or at times olive drab cardboard gave way to a distinctive color code, called in some circles either camouflaged or “morale” style. Breakfast units were printed in red, dinner units in blue, and supper rations in green. They also contained a malaria warning, instructions on how the inner cellophane bag could be used as a waterproof container, and for security purposes, printed directions that the empty can and used wrappers should be hidden.

For the most part, the inner carton did not change during the war. It was dipped in a solution of paraffin and bee’s wax to seal its contents from the elements. Very early units included a wax paper wrapping, but this was quickly abandoned due to cost. An added bonus to GIs was the fast-burning properties of the wax. Soldiers found it ideal to heat the ration’s meat component when set on fire. Both inner and outer boxes were perfect complements to each other, as the outer carton protected the wax coating on the inner box from rubbing off and sticking to other boxes. Typically 36 meals or 12 rations were packed into wooden crates weighing 40 pounds for shipment overseas.

105 Million Rations in 1944

The exact number of K Rations produced in World War II is hard to determine. After the government’s initial order in 1942 of one million, at least another million were procured in 1943, and 105 million in 1944, its peak year of production.

There is no question that the unpopularity of the K Ration with American soldiers can be traced to its misuse. Familiarity breeds contempt, and it was not uncommon for GIs to discard everything except the candy and cigarettes. Testimonials abound from soldiers nowhere near the battlefield being issued the ration. Others report it was given to them for weeks on end. While there were times when that practice was necessary, there were also times when it was used because the K Ration was the easiest to issue.

There is also no question that Keys’s vision of a small, lightweight, nutritious ration was a success. Paul McNelis, a decorated veteran of the Italian campaign with the 85th Infantry Division, has high praise for the ration.

“On the line we survived on K Rations,” he said. “Mules brought them up the mountains at night along with ammunition and water. We were happy to get them. C Rations were better of course. They had more of a variety like ham and beans. But we didn’t get any since they were bulkier, and we were being supplied by mules.

“If you were on the line, K Rations weren’t that bad. One good thing about them was that the box was impregnated with wax. There was just enough that when you set them on fire, it would warm a cup of coffee. A buddy of mine showed me how to make toasted cheese. You open the can, stick your bayonet in it and hold it over that fire to melt the cheese, and then put it on the crackers.”

With the end of World War II and peace at hand, there obviously was no longer a need for assault rations. The days of the K Ration were numbered. In 1946, an Army food conference recommended that its production be discontinued. In 1948, the Quartermaster Corps followed suit and declared the K Ration obsolete.

The Long Life of Ancel Benjamin Keys

While the usefulness of the K Ration on the battlefield faded into history, its inventor would go on to worldwide fame. Ancel Benjamin Keys was born January 26, 1904. A gifted intellectual, researcher, and scientist, he read in the obituary notices of the Twin Cities newspapers shortly after the war that a high number of Minneapolis business executives, wealthy men who presumably had some of the most lavish diets in the world, were dying from cardiovascular disease while people in postwar Europe, those with more modest diets, were not.

Following a 10-year study, Keys concluded that smoking, high blood pressure, and elevated cholesterol levels were common factors in heart attack patients. That led to his landmark Seven Countries Study in which he proposed that dietary fat is directly related to heart disease, and saturated fat in food is a determining factor in blood cholesterol levels. His revolutionary and bestselling book Eat Well and Stay Well popularized the so-called Mediterranean diet with its emphasis on regular exercise and a diet rich in plant foods, fresh fruit, and fish, landing him on the cover of Time magazine in 1961.

Keys retired from the University of Minnesota in 1972 and remained physically active for the rest of his life. He died on November 20, 2004. When asked at his 100th birthday party whether his diet had contributed to his long life, he reportedly answered, “Very likely, but no proof.”

Today, Keys’s legacy lives on for collectors of World War II memorabilia. Complete K Rations that show up on Internet auctions routinely sell for more than $200. Single components, even empty boxes, also sell well. But a note of caution to potential buyers of K Rations: while an unopened box might appear to be in pristine condition, collectors have found there is a very good chance that the contents have been sampled—by worms.

I belong to a local Civil Air Patrol Squadron and do research in varios tools, food, and supplie. This is done to better equip our people for search and rescue missions. I read every article that I can find about military field rations. During weekend camping trips I try out different ideas that I read about. We have developed our own versions of B Reation (hot meal in the feild), C Ration (cold canned mea; ), and D Ration (basic survival meal). When our squadron personnel go on a search and rescue mission (practice or actual) each person has a complete set of field gear, first atd pac, 2 of our C Rations, and 1 of our D rations

The figure of a day’s three-meal K Ration providing 9,000 calories is off by a factor of three. More like 3,000 calories, which weren’t always enough for people doing hard work, such as combat. In Italy, a medical officer noted men had lost weight and muscle tone through an overlong K-Ration diet.