By Leon Reed

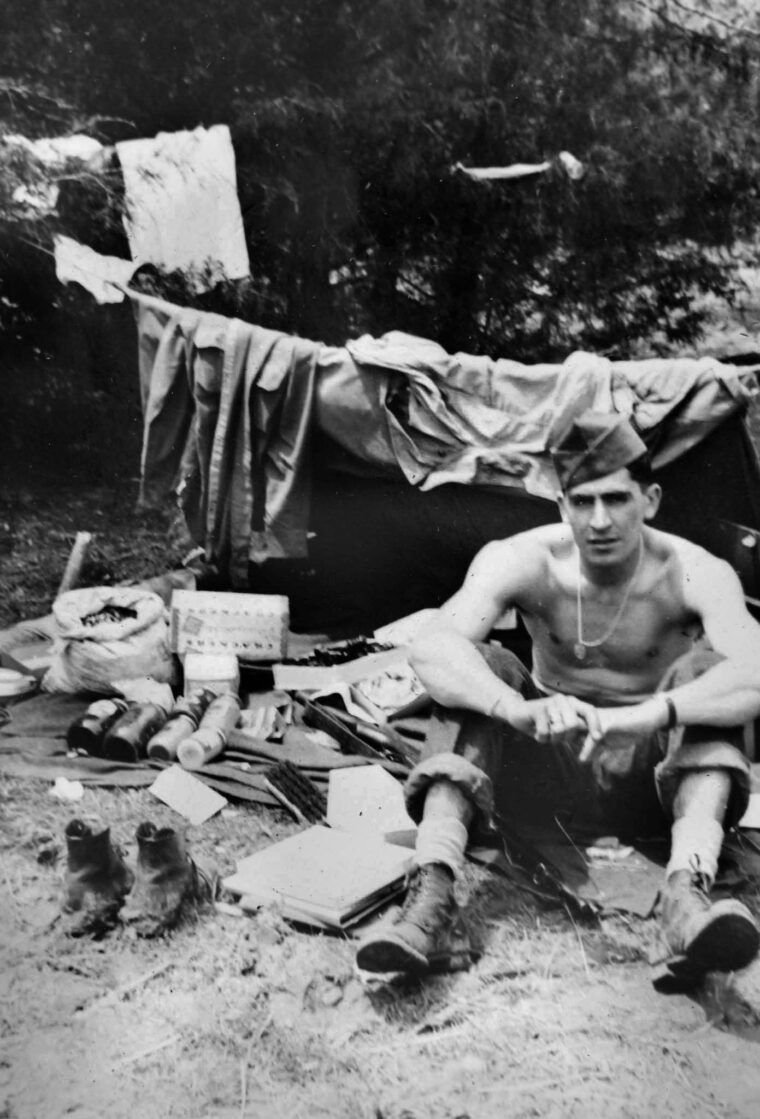

In a letter to his fiancée, Betty Craig, on December 16, 1944, from Helleringen, France, newly promoted Staff Sergeant Frank Lembo of Company B, 305th Engineer Combat Battalion, 80th Division, wrote of a battalion show the night before, complete with Red Cross girls serving donuts and the division band; an upcoming dance; doing laundry; and other pastimes of a soldier experiencing a period of reserve status.

Things were about to get hectic. It would be another nine days before Frank’s next letter, the longest period between letters to Betty during Frank’s three years in the army. In those nine days, the 80th commenced its attack into Germany but was ordered to halt, pull back, and redeploy to the north. The division raced 150 miles over clogged, icy roads to a different country, went into defensive positions, and launched an attack on Ettelbruck, Luxembourg, and other towns. Pulling out of combat and executing a 90-degree change of front were not the only challenges. There were no maps, and the Germans had had plenty of time to obstruct the route. The engineers led the way for the division, clearing mines, felled trees, and other obstacles.

First Lieutenant Walter Carr, deputy commander of Company E, 318th Regiment, described this movement in his memoirs. “With headlights blazing for the first time since I had been assigned to the 80th Division in Sept. 1944, we traveled all night. Early the next morning, as we passed through the outskirts of Luxembourg City, many of its residents lined the highway and cheered. We hoped that meant the war was over. North of the city we got jerked back to reality when we met a steady stream of refugees fleeing south to escape the Germans.”

Patton’s three spearhead divisions—26th and 80th Infantry and 4th Armored—went into action on December 22, 1944 at the height of the Battle of the Bulge. The 4th Armored Division was assigned to open a corridor to relieve the embattled garrison at Bastogne, Belgium. The 80th attacked Ettelbruck, southeast of Bastogne which sat on an essential German supply route, while the 26th attacked towns to the west.

Progress toward Bastogne was slow, and the garrison expressed impatience with the progress of the relief column. On December 23, acting 101st Airborne commander Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe commented, “I was disappointed I did not get to shake hands with you today.” And a staffer remarked, “A reminder, there is only one shopping day before Christmas.”

Finally, on Christmas Eve, Major General John Millikin, commander of the III Corps, ordered the commander of the 80th “Blue Ridge” Division, Major General Horace McBride, to release two infantry battalions, including Carr’s company of the 318th Regiment to join 4th Armored. Frank Lembo’s platoon was the engineering complement for this detachment. The 44 men in Frank’s platoon would be responsible for clearing mines and other obstructions and keeping roads open. Lembo commanded a third of the engineers. As a deputy company commander, Carr had shared responsibility for one-third of the riflemen.

The men of the 318th boarded trucks which followed a circuitous route to avoid German positions, driving carefully because of snow and ice, stopping frequently to ask for directions. Carr said when the convoy passed through Arlon, “We were surprised to see the city lit with Christmas lights and its citizens doing their last minute Christmas shopping. This was the first time in Europe we had seen people engaged in ‘normal’ life.” He added, “The Christmas decorations made some of us very homesick and we wondered if we would live to see decorations at home during later Christmas seasons. Too many wouldn’t.”

Progress from Niederfeulen, Luxembourg, to Burnon, Belgium, about seven miles south of Bastogne, was slow. The 35-mile trip on frigid roads took six hours.

The convoy arrived in Burnon, the furthest north point currently held by 4th Armored, after midnight. The tanks had advanced further north to Chaumont on December 22 but had been forced to retreat the next day when the Germans brought in five tank destroyers with long-range 88 mm guns. The infantry set about finding a place to sleep, but the engineers had an immediate chore: a preliminary survey of the roads north.

Frank wrote Betty a letter on Christmas Day. “I’m rather tired today, I didn’t get to bed until 5 a.m. (business stuff) and I was up at 8:30.” He gave a hint of the excitement, “The past week has been jam packed with things to write about, but until a future date it will have to be kept here.” Frank knew the censorship rules. There wasn’t a single censor mark on any of his 86 letters, so he knew when to be circumspect. “There’s fighting going on and over the next hill they are slamming away at each other.”

Apparently it was OK to talk about airplanes. “We have seen some good dog fights and yesterday I saw a Heine plane take a nose dive.”

Fortunately for the attackers, there were very few rivers and streams in this part of Luxembourg, so bridge building seldom delayed the movement. In general, when the infantry headed into fields the way was relatively clear but on roads mines and felled trees were a problem and the engineers had to clear the way.

The heavily depleted 2nd battalion started with 350 men, about a third of full strength, and had further losses on the way while fighting through the village of Chaumont on Christmas Day. Companies F and G occupied the high ground east of Chaumont, and Co. E fought its way in, clearing the town. The company was fortunate that its strength had been augmented that afternoon by 24 men transferred from the regiment’s Intelligence and Reconnaissance platoon, formerly led by E Company’s new commander.

Carr commented, “The struggle for Chaumont brought tragedy not only to Americans attacking the village but also to its Belgian residents. How well I remember an elderly, heartbroken Belgian couple who huddled in their small basement where some of us had taken shelter Christmas night. A fighter-bomber attack had wrecked everything they owned.”

The entire village of Chaumont was almost completely leveled after having exchanged hands at least four times from December 16-25. It was a key village U.S. forces had to control in the corridor being opened into Bastogne. Thirty miles away, Arlon residents were enjoying Christmas lights and last-minute Christmas shopping; here, it was a struggle for food, shelter, and survival.

The next day, the Americans took Grandru. An after-action report noted that they had “ventilated buildings with 57mm,” then moved as if to bypassthe town, then doubled back. By that time, Company F was down to 25 men, half a platoon, and was held in reserve the next two days.

About 10 Germans were entrenched in a patch of woods. To minimize excess casualties, the new company commander, Lieutenant Edmund A. Wellinghoff, radioed the battalion commander to ask for a tank “to help us roust the Germans out of their holes.”

Carr described, “When [the tank] arrived, Wellinghoff bravely stood beside it in the open space between the two wooded areas and used the outside mounted tank telephone to plan our attack with the tank commander. The Germans in their foxholes could have picked him off easily. But they didn’t because they feared that the tank commander would kill them rather than let them surrender to our infantrymen.”

Carr described the move forward. “From my position at the rear of the company, I kept wondering why we were waiting so long to renew the attack now that we had tank support. They didn’t stand a chance, and they knew it. But they did nothing until the machine gunner in the tank opened fire. Then they surrendered. Their defense had been unyielding against our infantrymen but not against our tank. They were as scared of an enemy tank as I was. Little wonder.”

Afterward, the surviving infantrymen moved without further opposition down a hill to occupy the village of Hompre. As soon as Company E arrived, Carr was summoned to battalion headquarters to receive orders to lead a patrol that night. Carr said, “I feared it would be my toughest and most dangerous mission of the war.”

On December 26, a detachment of tanks from Lieutenant Colonel Creighton Abrams’s Combat Command R of 4th Armored sprinted through German lines and linked up with the Bastogne defenders. Most historians consider this at least symbolically the end of the siege, though the supply line through Assenois was far from secure. In a show of Army parochialism, a 318th historian made it clear who he thought liberated Bastogne. “Early in the evening of the 26th, tank elements of the 4th Armored Division were able to get into the beleaguered city but unable to return.”

“‘Carr, we’ve selected you to lead a crucial patrol,’ Captain P.W. Foreman, the battalion S-3 [operations officer] told me. ‘Right now we’re about 3 miles south of Bastogne. After several more days of fighting, we expect to contact the 101st Airborne. We need to know exactly where their defensive positions are so we won’t shoot each other up when we try to make contact.’

“‘We want you to take a patrol into Bastogne tonight to bring back information on the positions of the 101st. But you’ll have to be very careful. We know you’ll have a tough time getting through to the 101st then back to us. But you’ve accomplished tough assignments before.’”

It wasn’t by accident that Carr got this assignment. Ever since October, when he was successful in capturing a German prisoner and bringing him back across the Seille River, he had become a sort of “night patrol specialist” for the battalion. Carr had mixed feelings about his fame. “I wasn’t totally happy with this assignment, but I probably did get some perks from it.”

On his way back to the company from battalion HQ, Carr analyzed the patrol’s mission. “We would have to sneak through the Germans facing us, then through the Germans surrounding Bastogne, contact the Bastogne defenders, then reverse the sequence to get back to battalion before it moved out the next morning.” This would require caution, but they couldn’t be too slow. “We would have to cover a total of six miles in less than 10 hours.”

Carr was sure that the most challenging task would be making peaceful contact with the Bastogne defenders. It might be possible to hide from the Germans while sneaking through their lines. But there was no way to avoid contacting the Bastogne defenders, and they might shoot at anything that moved toward them across the no-man’s land between themselves and the Germans.

Carr concluded, “Surely this was the last night of my life. The odds against success seemed overwhelming. I frankly didn’t know how we would make contact with the 101st. The only thing I could do was play it by ear.”

The patrol needed to be small. But it needed to be large enough to provide security in all four directions. Carr decided on four members, including himself, so he could use the diamond formation: one person forward and one back, one to the right and one to the left. Carr planned to bring up the rear. If the others got captured in an encounter with the Germans, he would be in the best position to escape to continue the mission alone. He got permission from Wellinghoff to go to his former platoon to get individuals he trusted.

Carr checked in with the platoon leader, Sergeant Virgil Miller. The officer in charge of the platoon had just been wounded that afternoon in the attack on Hompre. Carr was dismayed when Miller told him every one of the 40 members of the platoon Carr had known a month and a half before had been killed or wounded.

Carr quickly decided Miller would be an excellent second-in-command for the patrol, a point Miller further emphasized by volunteering. Carr let Miller pick the other two soldiers for the patrol, figuring he knew his men’s capabilities best. In the end, the patrol consisted of Technical Sergeant Virgil L. Miller, Elyria, Ohio, Pfc. Mulford E. Jones, Sarepta, Mississippi, Private Eddie Martinez, Houston, Texas, and 1st Lt. Walter Carr, Jr., Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Carr explained the mission and showed on a map how to get to Bastogne. He stressed that if anything happened to him, they must carry on. “I’ll bring up the rear of our diamond formation. From that position, I can more easily see and direct you. We need to remain in visual contact at all times. We’ll spread out going across the snow-covered fields and close up going through woods. Look at me frequently so I can direct you with arm and hand signals. I don’t want to alert the Germans with voice commands. If we tangle with the Germans, whoever survives will continue the mission.”

The patrol then set off for Bastogne, and Carr called the town “an objective I considered virtually impossible to reach. But I kept my pessimism to myself. It increased as we started across the huge expanse of open terrain. The snow made the night so bright we felt very conspicuous.”

The patrol had walked about a mile when Carr saw a village to the left. He assumed it was Assenois but needed to be sure, so he took over as point man because he could speak a little French, and walked over. The patrol was at first terrified when ordered to “HALT!” but quickly realized the sentry had barked “Halt” with an American accent, not German. After he briefly explained the mission, the sentry pointed to a nearby house where his company commander was located.

The company commander told Carr, “You’re in luck. We’re about to send a column of tanks and APCs (armored personnel carriers) into Bastogne. We may meet some resistance. But you’re welcome to ride in one of the APCs going in and coming back out.”

Carr and his patrol thanked their lucky stars and climbed into their assigned vehicle. The column made one lengthy stop, which they learned happened when the lead tanks “had to shoot our way through the Germans.”

When they arrived in Bastogne, they made their way to the 101st Division war room. They explained their mission to the division G-3, Colonel Kinnard. He gave them a mimeographed copy of a sketch map showing the perimeter dispositions of the 101st Airborne. Carr thought, “I was surprised he gave me the sketch; he might have been more reluctant if I had been returning on foot through German lines rather than returning by APC in a column protected by tanks.”

Folding the map, Carr told the patrol members to observe carefully as he put it in a field jacket pocket. “If anything happens to me,” Carr said, “whoever survives is responsible for removing the map from my pocket and getting it back to battalion.”

From Assenois the team hiked back across the snow-covered fields toward Hompre. As they approached the battalion’s defensive positions they got jittery wondering if their own troops would fire on them. But they arrived safely, as the battalion was getting ready to renew its advance toward Bastogne. Carr concluded, “As I walked through the door of the room where Captain Foreman had briefed me the previous afternoon, I heard a voice say, ‘Captain Foreman, it’s Lieutenant Carr. He’s back.’ I saw an expression of disbelief on Foreman’s face. I unbuttoned the flap on my jacket pocket. I unfolded the map and said to Foreman, ‘Here it is—exactly what you ordered.’ He couldn’t believe what he saw. It looked like I’d be keeping my job as patrol man for a while.”

On December 27, the Blue Ridgers fought almost to Assenois on the outskirts of Bastogne. Frank dashed off another letter: ““We’ve been away from our company and…today we are having a late meal. We’re up here (?) with some infantry and armor, or in other words we’re orphans again. The battle that was going on Christmas day is still going on in increasing fury. I guess something has got to give soon, and I doubt it will be us. I guess this damn war will never end.”

Early on the morning of December 28, the 2nd Battalion linked up with the Bastogne defenders. F Company’s 25 men, having been held in reserve the past two days, were assigned to outpost duty while E and G Companies got to warm up and get new clothes. Later that day, the task force members enjoyed a belated Christmas dinner in Bastogne. The author of an after-action report identified one benefit of heavy casualties. “Since rations had been drawn for 350 men, there was ample food for all.”

The German Bulge offensive shook the homefront and the frontline GI. Normally even-tempered and upbeat, Frank wrote, “I’m pretty darn disgusted with everything over here. We fight like heck and then someone screws up and Heine sets us for a loop, but at home no one seems to care, and here we beat our heads for nothing.” Later, he added, “From the looks of things we’ll have to fight our way right to Berlin, and I hope we burn that path soon. We all thought this war was over, and I guess the only way to get it over with is to destroy Germany, her soldiers, her civilians, and the ground they live on.”

After Bastogne, the 80th Division went into reserve status. Carr summarized, “As survivors of the Bastogne combat action, we were too psychologically battered to be in the front lines. We needed a rest from front line action if we were to be prepared to carry out our next combat assignment successfully. We had suffered a significant number of casualties. We had gone to Belgium in 21 trucks but needed only nine to return.”

Frank, too, enjoyed the slower pace, writing Betty on January 1, “Today was a simple GI day for us here, we finished a bridge we started yesterday and late in the afternoon we had a turkey dinner.”

Perhaps it was the Bastogne mission fresh in his mind that caused Frank to take stock. On January 2, he wrote Betty, ““I was just thinking about that last day together that we had, and how perfect it was, and how long a way I’ve come since then. I can remember that boat ride to England, our trip across the Channel, going into action and suffering a thousand deaths when we heard our first artillery shell, the mad dash across France—a ride with its wine, flowers, ripe tomatoes and eggs—the storming of our first river and the fighting beyond, Christmas in Belgium, New Year in Luxembourg…Yes, we’ve come a long way. We’re a little tired, a little older, and a little bitter. We fight hoping each battle is the last one with thoughts of going home and enjoying a peaceful life, our thoughts run to our sweethearts who we long for, each letter being a five minute furlough with the one you love.”

After Bastogne, another month of hard fighting remained before the bulge was reduced and the Germans were pushed back to their starting position. And then came the 80th’s toughest river crossing of the war—the Sauer/Our—and then spring and the liberation of prison camps. In the end, Hitler’s counteroffensive probably did hasten the end of the war, but not in the way he intended. The men and equipment left in the fields and forests of the Ardennes—and the thousands who surrendered—weren’t available the following spring to defend the Siegfried Line and the Fatherland.

Leon Reed is a former U.S. Senate aide and U.S. History teacher. He is the co-author of (with his wife, Lois Lembo) A Combat Engineer with Patton’s Army: The Fight Across Europe with the 80th “Blue Ridge” Division in World War II (Savas Beatie, 2020) and is currently editing Walter Carr’s memoirs and writing a book on army training in World War II. He is the editor of Bulge Bugle, the quarterly magazine of the Battle of the Bulge Association.

My wife’s father was in the 80th. He kept a small diary of his experiences and some pictures. I would love to share this with others and try to piece together his experience in the war.

No a M4 Sherman but a M3 Stuart. Pretty basic mistake to make. Why?