by Robert Heege

It was spring 1944, and the morning sun was glinting off the face of the water as the Landing Ship, Tank (LST) transports chugged their way through the choppy surf and headed in close toward shore, their destination a gravel-strewn stretch of beach on the English Channel code named “U” for Utah. Moments later, as shells began raining down all around the LSTs, America’s pride, the brave boys of the U.S. Army, grabbed their rifles and sprang into action. In a matter of seconds, as what sounded like a million machine-gun nests ripped the air asunder, sending deadly, clattering volleys of lead whizzing above their heads, the resolute young infantrymen were slogging through the waves, tearing through the tide pools, and storming the beach.

Some of them, a handful of hardy survivors, had already come through the landings in North Africa in 1942 and the invasion of Sicily in 1943. For a great many others, new to the service and still so very young, it was their first real experience of combat conditions. It would also be their last. Within seconds, all of them, the veteran campaigners and the green recruits alike, were being decimated. They were cut down by the bushel and blown to bits by devastating shellfire. The dead and the dying were everywhere. The desolate, deserted stretch of beach ran red with their blood. Transformed in an instant, it had become a slaughterhouse.

One of the Largest, Most Ambitious Training Exercises Ever Conducted

This was not D-Day, June 6, 1944, the Allied landings on the Northern coast of France, the opening shots of the long-awaited second front in Europe, that great clash of arms in the titanic struggle against Hitler and his Nazi tyranny for the liberation of an enslaved Europe. This was not the invasion of Normandy; for that matter, it was not even Normandy. It was the east coast of England in late April 1944, a little more than a month before the real landings across the English Channel in German-occupied France.

As training exercises go, Exercise Tiger was one of the largest and most ambitious ever conducted. It was also an unmitigated disaster. As a full-scale rehearsal for D-Day, it was planned and carried out under conditions of utmost secrecy. The appalling carnage that ensued, even the fact that it had occurred at all, was a high-level state and military secret. Army surgeons were threatened with court martial for even speaking with the wounded. Even the casualty lists were kept strictly under wraps. To this day, it remains perhaps the most underreported story of World War II.

On December 11, 1941, a scant four days after Japan’s sneak attack on the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, German leader Adolf Hitler, in an ecstasy of megalomania, decided that Nazi Germany also should declare war on the United States. The immediate result was that the full weight of America’s industrial and military might were now firmly and finally in the fight against the Third Reich.

Men and materiel flooded across the Atlantic in an enormous, seemingly never ending supply chain of Liberty ships, troops, tanks, and planes. There were so many U.S. servicemen in the British Isles by 1944 that England had begun to resemble one gigantic American troopship. After four long years under the Nazi boot, the stage was set, at last, for the first phase in the struggle to retake western Europe, a combined British-American landing on the coast of France.

Staging D-Day at Slapton Sands

Accordingly, toward the end of 1943, America’s British allies in concert with the U.S. government and its military leaders began the herculean logistical task of preparing for Operation Overlord, the top-secret plan of attack designed to tackle that objective. As part of that mission, the British, in the best cloak-and-dagger tradition of a James Bond novel, created an ultra-secret training ground in Devon on the east coast of England.

The spot designated, known then as Slapton Sands, was remarkably well suited to the task as its topography closely mirrored that of a stretch of territory along the coast of northern France upon which the genuine landings would soon take place. With its gravel beach fronting a spit of land and a small lake just beyond in the interior, Slapton Sands was a near dead ringer for what would become known to history as Utah Beach, one of the two landing zones in Normandy assigned to the American forces.

No less than three of these secret war games were conducted along the English coast starting in December 1943. Exercise Tiger, the last and the most comprehensive of the three, was designed to hammer out every possible detail related to the vast undertaking that lay ahead, the long-awaited assault on Hitler’s Atlantic Wall.

Keeping a Lid on Allied Activity

Trying to keep the lid on something as conspicuous as a mock seaborne invasion during wartime was a nightmare for the British Security Service, especially in Great Britain in 1944, an island nation groaning under the weight of millions of civilians, war industry workers, and Allied servicemen cramming in from every corner of the world. It proved to be no easy feat.

To begin with, the more than 3,000 people who called this quiet corner of England home were stunned to find themselves being issued evacuation orders and summarily relocated. In this manner, entire communities were transformed into eerie ghost towns almost overnight as the now deserted area was virtually sealed off from the outside world by a scrupulously enforced military cordon. The stage was now set.

The first phase of the exercise was scheduled for April 22 and 25. It consisted of a series of drills that involved loading large numbers of soldiers on the LSTs at various embarkation points along the English Channel and ferrying them to their assigned landing zones in a timely manner. Mastering this challenge was vital to the future success of Operation Overlord, and it needed to be accomplished without being detected by the enemy.

To that end, two British Royal Navy destroyers, three torpedo boats, and two motor gunboats bristling with .303 Vickers machine guns, depth charges, and 6-pounder cannons put to sea to keep the waterways leading in and out of nearby Lyme Bay away from the prying eyes of the enemy. Specifically, the focus of their mission was to keep a sharp lookout for any sign of their German opposite numbers, the dreaded Nazi E-boats that regularly operated from their base near the French port of Cherbourg on the other side of the English Channel from Britain, a distance of barely 21 miles at its narrowest point.

H-Hour: 7:30

During Exercise Tiger, sleepy, moribund Lyme Bay had its own unique role to play standing in for the English Channel. On the night of April 26, the first contingent of troops formed up in its assigned embarkation depots and marched dutifully up the gangplanks and onto the LSTs that would ferry them to Lyme Bay. To get the men used to the rigors of a genuine Channel crossing, the LSTs proceeded to chug their way around the bay in a wide arc to simulate the journey to the Normandy coast, then made for the waters just off Slapton Sands. They were to arrive there just before dawn on the morning of April 27.

H-hour, the commencement of the mock landings, was scheduled for 7:30 am. The vital importance of communication and coordination and the challenge of keeping everyone committed to their respective timetables were about to become readily apparent. Just before the first wave of the “assault,” a live-firing exercise was to be conducted to give the men a small taste of the sensory experiences that they could expect to encounter when they hit the Normandy beaches during Operation Overlord. Not only would genuine bullets be fired directly over their heads as the men came ashore, but Britain’s Royal Navy was directed to shell the beach for a half hour beforehand as the LSTs made their approach.

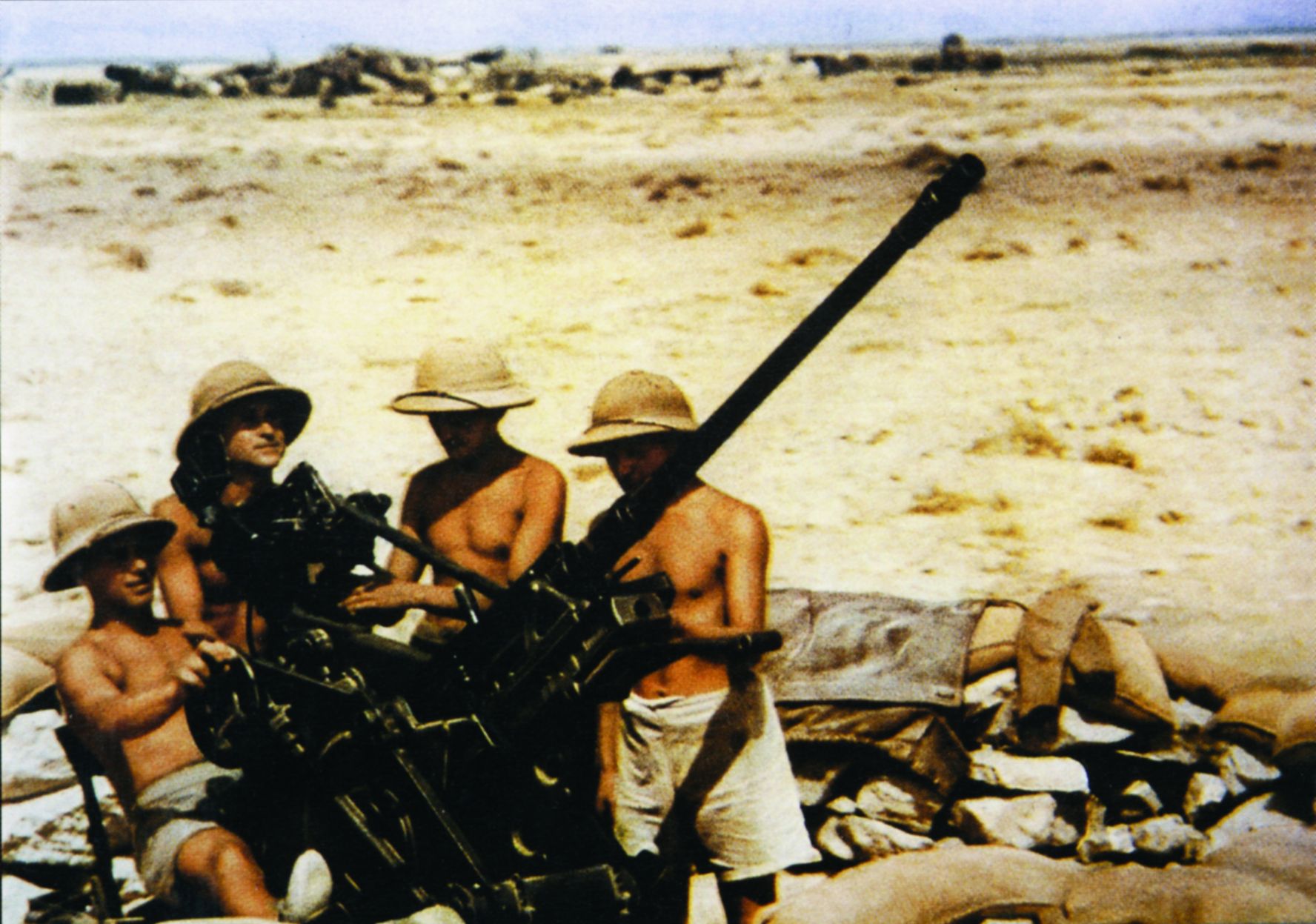

The bullets and the bombardment were mostly the brainchild of the-Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force and originated with none other than Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Having successfully overseen the American landings in French North Africa during Operation Torch in 1942 and the Anglo-American invasion of Sicily the following year, Eisenhower, while not a battlefield general in the traditional sense, was nevertheless no martinet.

Shaking Out the Complacency in the Younger Troops

Far from it, he was a man who cared deeply about the GIs he was sending into harm’s way and had become increasingly concerned by the youthful inexperience and relative naivete of the ever increasing flood of conscripts, who were arriving in England as fast as the U.S. draft boards could get them there. They were all there to do their duty, many all too eager to get into the fight, but the overwhelming majority had never seen action before. Revved up back on the home front by a steady diet of Errol Flynn and early John Wayne movies, some of them were jovially sounding off in their barracks and pup tents as if they expected the liberation of Europe to be an easy victory.

Eisenhower knew this because he took the time to regularly visit the encampments and the training grounds to talk to these young Americans face to face, and he came away convinced that it was of vital importance to shake the complacency out of these teenage boys, which is what they were in large part, and toughen them up for the ordeal that he knew all too well lay before them.

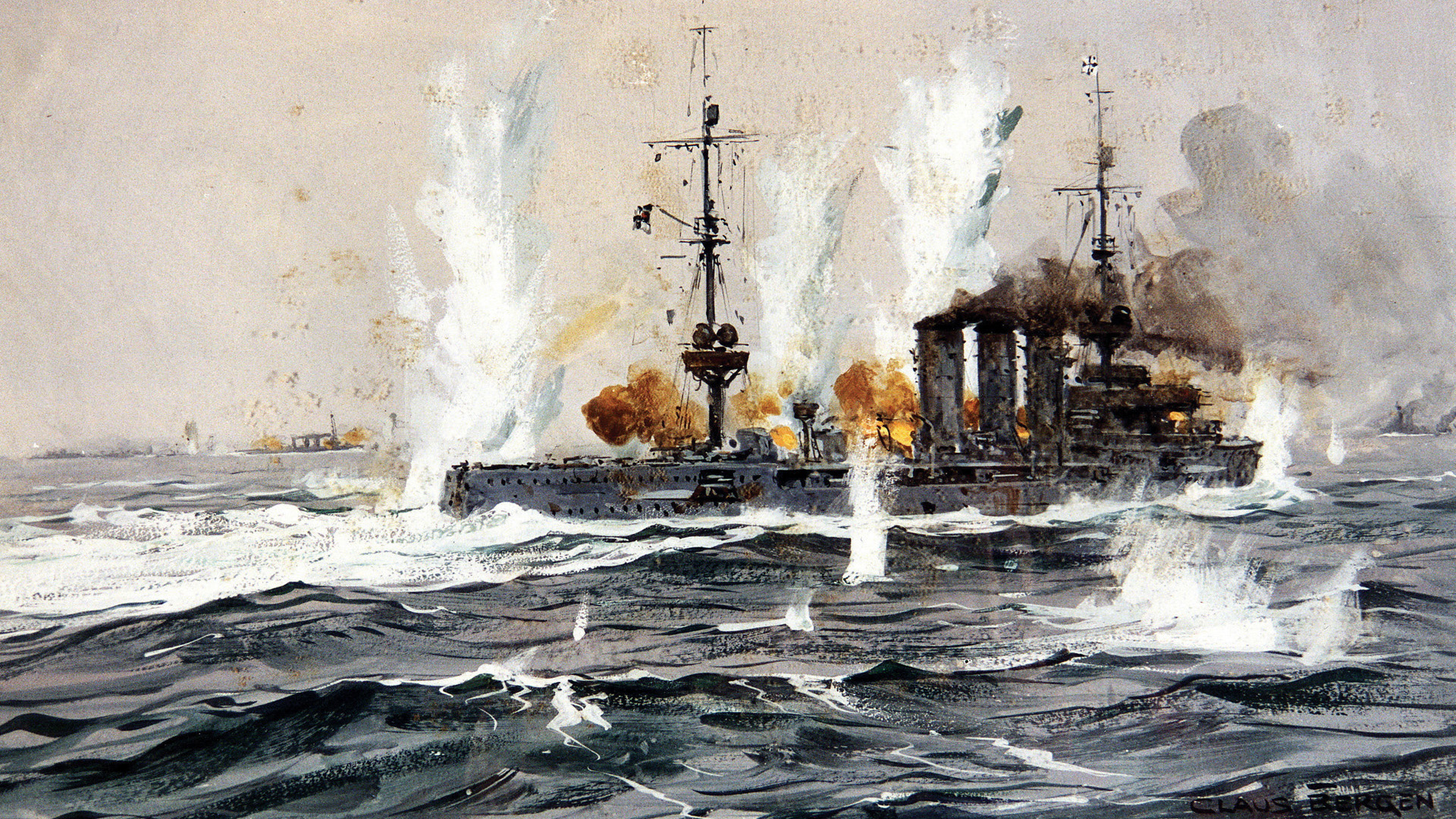

Accordingly, a British Royal Navy heavy cruiser, HMS Hawkins, sat offshore ready to begin subjecting the beach to a genuine naval bombardment set to begin at precisely 6:30 am and end promptly a half hour later. This would give the beach wardens at Slapton Sands 30 minutes to inspect the beach for unexploded ordnance and certify that the area was safe for the troops to make landfall as scheduled, at 7:30 am on the morning of the April 27.

How It All Went Wrong

Tragically, it was at this point that things started to go terribly wrong. The trouble began when some of the ships participating in the exercise fell badly behind schedule that morning, a delay that was soon rippling through the exercise’s entire timetable. As a result, American Rear Admiral Don Pardee Moon, the officer in command of the exercise, made the snap decision to postpone the live-fire portion of the exercise by a full hour and the subsequent landing of the troops on U-Beach to 8:30 am.

Moon, an Indiana native with a service record stretching back 28 years in the U.S. Navy, was no 90-day wonder. He was a conscientious, experienced professional, a veteran of World War I. Two years earlier, he had participated in Operation Torch, ably discharging his duties during the successful North African landings, and as a result was tapped to command Exercise Tiger.

Moon’s message, ordering a one-hour delay to allow the latecomers to play catch up, was promptly relayed and duly received by the Hawkins. But crucial radio frequency errors between British and American radiomen resulted in needless suffering. Several of the LSTs that had managed to keep to their schedule that morning were already approaching their assigned objectives, and they failed to receive this vital communiqué. On that fateful April morning in 1944 it was a mind-numbingly simple and also lethal recipe for disaster.

Unaware that both the live-fire battle simulation and H-hour had been delayed, several LSTs, still adhering to the exercise’s initial timetable, made landfall and disembarked their men at Slapton Sands just as the now rescheduled naval bombardment began raining shells down on the beach. Soldiers that had never really expected to be placed in harm’s way in what was supposed to be a simulation, albeit an ultra-realistic one, suddenly found themselves in danger of being blasted to pieces. According to plan, the machine guns firing just above their heads had also been directed to fire a few bursts into the ground a few yards ahead of the landing zone on U-Beach for the added benefit of the infantrymen as they came ashore—a realistic touch that was to have chilling consequences.

Friendly Fire Casualties Across the Beach

As the machine gunners’ bullets began tearing up the gravel directly in front of them, the now understandably bewildered soldiers reacted like a clutch of startled bumblebees. Worse still, the soldiers hitting the beach had been ordered to return fire at their imaginary enemy as they went forward as part of the simulation. Many did so, apparently under the impression that they had all been issued blank cartridges. However, the GIs on the beach that day had inadvertently loaded up their rifles with real ammunition instead of blanks. Bunched up as they were, some of the boys became the unwitting casualties of friendly fire. Meanwhile, according to plan, the Hawkins continued its bombardment, pouring ordnance into a designated section of the beach that the beach wardens had obligingly marked off for the naval gunners with a cordon of white tape. In the ensuing chaos and confusion, scores of soldiers desperately attempting to get out of the line of fire strayed across the white demarcation line and ended up directly in the kill zone. As the officers on the bridge of the Hawkins looked on in stunned horror and disbelief, these unfortunate souls were practically vaporized, blown to bits by the Royal Navy’s big guns.

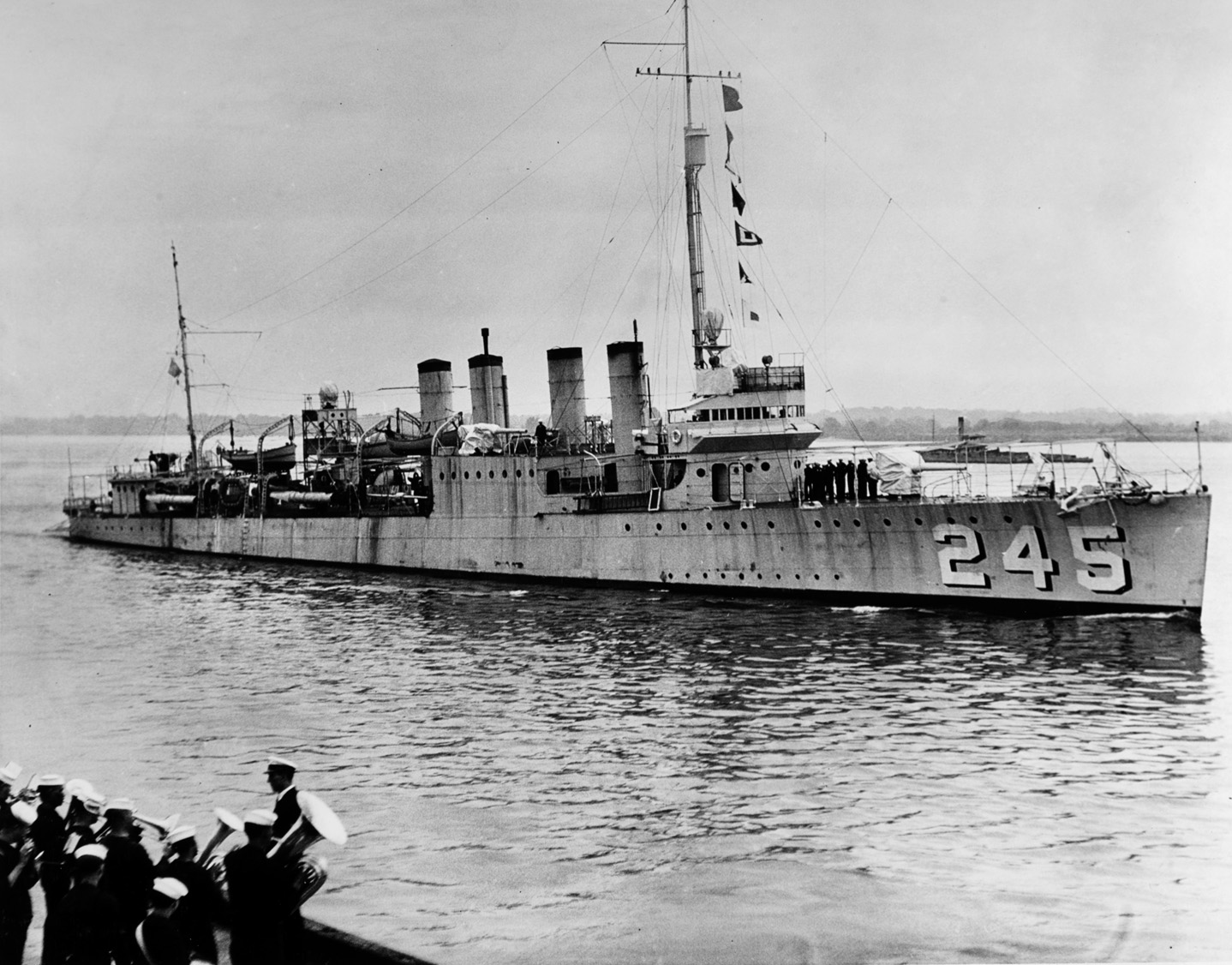

During the early morning hours of the April 28, a second larger convoy of LSTs bristling with young Americans of the 4th Infantry and 1st Amphibious Divisions, combat engineers, tanks, trucks, and all manner of vehicles and equiment of the U.S. 1st Engineer Special Brigade took a second crack at a beach landing. This also ended in complete catastrophe. One of the two escort ships assigned to protect the LST flotilla, the World War I-era destroyer HMS Scimitar, had incurred some structural damage during an earlier collision with another vessel and had to break off and head back to Plymouth for repairs, leaving only a single corvette, the HMS Azalea, to escort and protect the LSTs. Incredibly, once again, British Royal Navy headquarters and the Royal Navy ships participating in the exercise continued to transmit to each other on a different radio frequency than the Americans on the LSTs. As a result, communication between the two broke down once again.

Rather than zigzag, the Azalea opted to lead the eight LSTs in a straight line, making these slow moving transports easy prey for any of the super swift E-boats routinely prowling the English Channel. Other Allied ships and the coastal shore batteries at nearby Salcombe Harbor had, in fact, spotted the telltale silhouettes of several E-boats in the vicinity some hours before, skimming low across the waters like hungry sharks in the dark of night. The Azalea was duly informed. The LSTs were not.

Sitting Ducks for E-Boats

A German night patrol consisting of nine Eboats was just preparing to return to Cherbourg when the early morning light presented them with a tempting target: a daisy chain of eight heavily laden, ridiculously vulnerable craft, each one neatly spaced out at a distance of about 500 yards from the one in front of it, plodding through the waves toward the English shore like so many slow-moving sea beasts. Moments later, all nine E-boats moved in for the kill.

Lined up as they were, the LSTs were sitting ducks for the E-boats’ hit-and-run tactics. LST531 was torpedoed and sent straight to the bottom, another, LST-507, was set completely ablaze, sending soldiers weighed down by their gear scrambling over her sides into the frigid waters of the English Channel. Two other LSTs, though badly damaged in the attack, somehow managed to limp back to port. LST-289 was still smoldering. The other, LST-511, had been shot up by her own escort as it returned fire at the enemy. The E-boats, apparently satisfied with the evening’s carnage, called it a night and returned safely to base.

More than 441 American soldiers and 197 sailors died of wounds. Upward of 111 souls were either taken by the sea, succumbed to the effects of hypothermia afterward, or were casualties of friendly fire at Slapton Sands, according to the U.S. government. But documentation recently released under the Freedom of Information Act suggests that the authorities deliberately sought to minimize the casualty reports. This development might push the death toll as high as 946, meaning that more Americans actually died during Exercise Tiger than in taking the real Utah Beach on D-Day itself.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments