By Patrick J. Chaisson

Sergeant William R. Kelly crashed through the treetops, slamming to a stop when his parachute canopy caught on some branches. Hopelessly entangled in his suspension lines, the Canadian paratrooper found himself hanging upside down with his face immersed in fetid swamp water. Kelly found he could breathe only by lifting his head up against some 60 pounds of equipment pressing against him. Wearying rapidly, the exhausted para wondered if each gulp of air might be his last.

Throughout the early hours of June 6, 1944, more than 20,000 American, British, Canadian, and Free French airborne soldiers jumped or rode by glider into Normandy, France, as the advance guard of a massive Allied invasion code-named Operation Neptune, the invasion phase of the Operation Overlord, the Allied assault against Hitler’s Fortress Europe. It was pure chaos. A combination of poorly marked drop zones (DZs), vicious German antiaircraft fire, and inexperienced troop carrier aircrews conspired to scatter most of these parachutists all over the Norman countryside.

Some jumpers, misdropped over the English Channel, disappeared without a trace. Others, like Sergeant Kelly, landed far from their DZs in marshes or flooded areas. For these men, survival often depended purely on luck. Kelly was fortunate; other Canadians heard his struggles and quickly cut him loose.

Sergeant Kelly cheated death that night but could not stop to celebrate his deliverance. He knew Operation Neptune’s success depended on the airborne forces to carry out their vitally important missions. Thousands of paratroopers—soaked to the skin, lost, cut off from their officers and with much of their heavy equipment missing—nevertheless began advancing toward the objective.

Canada, one of the Allied powers, watched with alarm as German sky soldiers spearheaded the Axis conquest of Belgium, Norway, and Crete in 1940-1941. While determined to form its own airborne force, Canada’s War Cabinet recognized this would be possible only with considerable support from its British and American allies. Arranging that assistance took time, but finally on July 1, 1942—Canada Day—the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion (1 CAN PARA BN) was established. Major Hilton D. Proctor became its first officer in command.

The organization consisted of four companies: three maneuver units designated A, B, and C Companies, as well as Headquarters Company, which contained heavy weapons, signals, administrative, and intelligence elements. A total of 26 officers and 590 enlisted soldiers made up the battalion’s wartime strength, with recruits coming from across the Canadian Army. Unit leaders wanted tough men for a tough job. The ideal volunteer was “under 32 years of age, with a history of participation in rugged sports or in a civilian occupation or hobby demanding sustained exertion.” Soldiers training in Canada, and those already deployed to the United Kingdom, were all accepted for parachute duty.

As Canada did not yet possess a jump training facility, volunteers were sent either to the British parachute school at RAF Station Ringway or the U.S. Army’s airborne center at Fort Benning, Georgia. Approximately 85 soldiers went to Ringway, where during a demanding 16-day course they made eight jumps from tethered balloons and British drop aircraft. Everyone else, however, trained with the Americans.

Starting in August 1942, about 55 Canadians per week entered the arduous month-long basic parachute course at Fort Benning. Brutal heat and merciless Yank instructors tormented the trainees; men “double-timed” everywhere while push-ups—dozens of them—became a favorite punishment for even the slightest infraction. Officers and men suffered alike, although some enlisted soldiers delighted in “throwing the lieutenant around” during judo training.

Students were reminded of parachuting’s special hazards when on September 7, 1942, their battalion commander, Major Proctor, was killed while making his first jump. Lt. Col. George F.P. Bradbrooke stepped forward to replace Proctor, and training continued.

Becoming jump-qualified filled every man who completed the course with a sense of pride and confidence. “They felt they could take on the world,” remembered Private E.J. Scott. Paratroopers also enjoyed wearing the symbols of their new status: a maroon beret, jump wings, and the blood-red Corcoran boots issued at Benning and bloused in the American style.

While some Canadians remained behind to receive additional instruction in communications and parachute rigging, most of Bradbrooke’s soldiers moved on to their new base at Shilo, Manitoba, in April 1943. This facility was still not ready for them, however. A shortage of everything from uniforms to weapons to jump aircraft meant there was more “make-work” on the schedule than actual combat training. Many men, their bodies and spirits honed to a fine edge of readiness, rebelled against this enforced inactivity.

At the same time, discussions between Canada and the United Kingdom resulted in the assignment of 1 CAN PARA BN to the British 6th Airborne Division (6 AB DIV) for duty overseas. Upon learning this news, the men celebrated. Soon they would experience the action that each soldier had struggled so hard to experience. Few realized then that the Canadians’ training had just begun.

Following an uneventful Atlantic crossing in late July 1943, the paratroopers of 1 CAN PARA BN moved to Carter Barracks, Bulford Camp, on Salisbury Plain in central England. There they learned their outfit was now part of 6 AB DIV’s Third Parachute Brigade (3 PARA BDE), commanded by Brigadier S. James Hill. Nicknamed “Speedy” for his blistering pace on forced marches, Hill was a 32-year-old professional officer who had commanded the British First Parachute Battalion during heavy fighting in North Africa.

Brigadier Hill extended a warm welcome to his Canadians. After inspecting the battalion, he wrote of its men, “These were soldiers who wanted to fight and the sooner the better.” But, Hill cautioned, an aggressive spirit alone will not win wars. As 1 CAN PARA BN settled in, he took note of the unit’s many training deficiencies that would require correction before it was ready for action.

First, every trooper who had qualified at Fort Benning required familiarization on British parachute equipment and techniques. This meant attending a conversion course at Ringway, which upset many men until they realized the RAF instructors there behaved far more humanely than their American counterparts back in Georgia. Canadian paratroopers liked the British “X” harness and its quick-release buckles, while the landing falls taught at Ringway proved superior to the U.S. method.

They did not like how the British exited an aircraft. For delivering paratroops, the RAF modified obsolete bombers by cutting a circular hole in the belly through which jumpers dropped. Men who did it wrong “rang the bell” by striking their jaw on the rim as they exited, usually resulting in the loss of a few teeth. Unlike the Americans, British paras did not use reserve parachutes—a cost-saving measure that unnerved some Canadian jumpers.

But the worst blow to the Benning-trained paratroopers’ morale came down in an order requiring them to remove their American jump boots. Maintaining the proper uniform was a key element of unit discipline, so the men (with much grumbling) put aside their prized Corcorans for the black brogans and web anklets worn by all members of 3 PARA BDE. They were now ready to train.

Fortunately, there was no better training officer in the Royal Army than Brigadier Hill. “My four rules of battle,” he explained to the Canadians, were “number one, speed—we [have] to get across country faster than anyone else; two, control—no good commanding unless you have discipline and control; three, simplicity (in thought and action); and four, effective fire power or fire effect.”

The battalion’s most glaring deficiency, Hill saw, was marksmanship. “As a parachutist,” he noted, “you have the minimum of ammunition to accomplish the stiffest task.” This meant that “every shot must be fired to kill.” Canadian paras spent many hours on the range, bringing their skill with rifle, pistol, Sten, and Bren guns up to 3 PARA BDE’s exacting standards.

Another vital component of Brigadier Hill’s individual training program was physical fitness. Every day after reveille there was a two-mile run, followed by calisthenics designed to build stamina. The battalion also regularly made forced marches with full battle kit in all weather. Every month unit members walked 15 miles in three hours while carrying all their equipment, and in October 1 CAN PARA BN shattered brigade records by finishing a 50-mile road march in 17 hours flat.

As winter approached, Hill’s focus turned toward unit level training. Together with the rest of 3 PARA BDE, the Canadians conducted several large-scale field problems held as rehearsals for the coming invasion of Western Europe. Junior officers learned to control their platoons while all ranks practiced taking on leadership roles in case their commanders were lost, captured, or killed. Observing these exercises, Hill would occasionally stop a private soldier and quiz him on the mission.

The fiercely competitive Canadians had been hardened physically and mentally during their time in England. They could shoot, move, and communicate as well as any para and were especially skilled in the art of night fighting. The battalion also possessed a unique sense of initiative. Each man understood what had to be done to achieve his unit’s assignment and could be trusted to act in the absence of orders. They were ready.

On May 31, 1944, the soldiers of 1 CAN PARA BN moved to a transit camp near the airfields from which they would depart for France. Officers and men gathered in heavily guarded briefing tents to examine terrain models of their objectives in France. They learned they were jumping into Normandy, near the city of Caen, with orders to cover the east flank of the entire Allied invasion.

The ground there was divided by two rivers, the Orne and the Dives. Several bridges spanning these waterways would, if captured or blown, restrict enemy movement throughout the region. High ground dividing the Orne and Dives River valleys, known as the Bavent Ridge, dominated the surrounding pastureland. Thickly wooded hedgerows, which the French called bocage, split farmers’ fields and made for excellent defensive terrain.

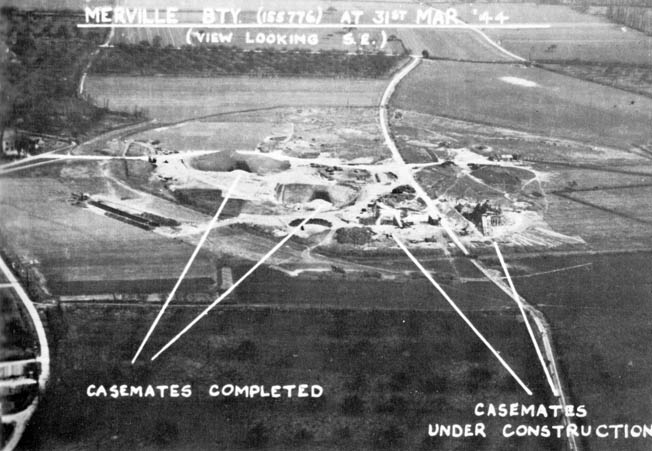

The Orne and Dives bridges were major objectives. Furthermore, enemy gun emplacements at the Merville Battery posed a severe threat to the Allied landing beaches and had to be seized. German troop concentrations in the villages of Varaville and Bréville blocked access to the Bavent Ridge—these strongpoints also needed to be neutralized. Otherwise, an enemy counterattack coming down off this high ground could drive a wedge into the Allies’ flank and possibly doom the entire invasion.

Opposing 6 AB DIV was a jumble of second-rate coastal defense troops backed by well-equipped veterans and PzKpfw. IV tanks. Occupying positions along the Orne River estuary was the 716th Infantry Division, led by Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Richter. Lt. Gen. Josef Reichert’s 711th Infantry Division held a portion of the Normandy shore from the mouth of the River Dives eastward past Caen. These so-called static divisions were manned by low-quality soldiers (including Russian, Polish, and Ukrainian “volunteers” led by German officers) and had little in the way of transport or supporting artillery.

More formidable was the 21st Panzer Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Edgar Feutichtinger. Stationed east of Caen, this mechanized formation was kept in reserve for use as a counterattack force. Efficient and heavily armed, the 21st Panzer could pose a serious threat to lightly equipped Allied paratroopers.

Indeed, the men of Maj. Gen. Richard N. “Windy” Gale’s 6 AB DIV faced many challenges as they prepared to invade Normandy. Their mission was straightforward—protect the landing beaches from German counterattacks—but executing this task required daring, split-second precision, and not a little luck.

Both of Gale’s parachute units, 7,000 men of the 3 and 5 PARA BDEs, would jump starting at 0020 hours onto DZs between the Orne and Dives. Their mission was to rapidly seize or demolish a number of bridges in the region before enemy garrisons could react. Part of this scheme included a coup de main in which six glider loads of infantry would grab intact key crossings over both the Caen Canal at Benouville and the Orne River near Ranville. The 6th Airlanding Brigade, coming in by glider later on D-Day, acted as Maj. Gen. Gale’s battlefield reserve.

The key task of destroying the Merville Battery went to Brigadier Hill’s 3 PARA BDE. Hill in turn gave this tough assignment to his 9th Parachute Battalion, reinforced by engineers equipped with flamethrowers and explosive charges deemed necessary to disable the four 150mm guns supposedly emplaced there. The 8 PARA BN, another element of Brigadier Hill’s command, was charged with wrecking several strategic bridges near the villages of Bures and Troarn.

Lieutenant Colonel Bradbrooke’s 1 CAN PARA BN also received a challenging assignment. The Canadians were to neutralize an enemy strongpoint and secure the brigade DZ at Varaville, as well as help demolish a number of bridges outside that village and farther east at Robehomme. A final task was to cover 9 PARA BN’s assault on the Merville Battery. Once they completed these missions, the Canadians would seize and hold the hamlet of le Mesnil, a strategic crossroads on the Bavent Ridge.

Bradbrooke’s men spent days analyzing the mission. Company C, Major H. Murray MacLeod commanding, was responsible for protecting the pathfinders who were to mark DZ “V” west of Varaville. They would then capture a command post in town and assist British sappers with the destruction of a nearby bridge. Company A, under Major Don Wilkins, drew the difficult job of guarding 9 PARA BN’s flank as it assaulted the Merville Battery. Soldiers of Company B, led by Major Clayton Fuller, would blow the span at Robehomme before rejoining their battalion at le Mesnil.

The Canadian plan was a risky one. Its success depended on many factors. Above all, 1 CAN PARA BN had to be dropped accurately and on time. Bradbrooke’s soldiers would then need to assemble quickly, recover their equipment, and strike out for widely separated objectives at night against a determined, well-prepared enemy. They were about to prove their fitness, fighting skills, and initiative in the ultimate test of war.

As the men assembled one final time at their transit camp, many paras contemplated how they would perform in battle. Brigadier Hill, no stranger to combat himself, stepped forward to offer words of encouragement and warning: “Gentlemen, in spite of your excellent training and detailed briefing do not be daunted if chaos reigns—for it certainly will.”

Those who survived the Normandy drop would later remark how prophetic Hill’s comments were.

Late in the afternoon of June 5, the soldiers of 1 CAN PARA BN began moving to their departure airfields. Company C emplaned at Harwell, flying in converted Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle bombers of 38 Group, RAF. The rest of the battalion was trucked to Down Ampey, where Douglas C-47 Dakota transports crewed by 46 Group stood by.

At Down Ampey, Chaplain George Harris “was waiting with a prayer book in his hands,” as one correspondent described. “His face was daubed with camouflage paint, he wore a green jumping smock and there was a crash helmet at his feet. The Canadians knelt and, as a stormy sun set over the woods, prayed and sang a hymn. After the blessing they turned, buckled the last straps, and filed to the planes.”

The jumpers, overloaded with parachute, ammunition, and equipment, had to be pushed into their aircraft. Sergeant Dan Hartigan reported that “every man carried two pounds of plastic explosive primed with a screw-cap detonator, a No. 74 antitank grenade, several Mills bombs, and, in the assault companies, every second man carried four loaded Bren machine-gun magazines or four two-inch mortar shells, and smoke bombs for covering assaults.” Many Canadians stuffed extra gear into leg bags, which they were to carry out the door and release before landing. Vickers machine guns, radios, and three-inch mortars were packed into containers and dropped along with the paras.

One jumper, however, leaped eagerly into the Dakota that would take him to battle. Jonny Canuck, an Alsatian/shepherd mix, served as the battalion’s war dog. Jonny and his handler, Sergeant Peter Kowalski, would parachute into France to provide early warning of enemy infiltrators thanks to the canine’s specially trained nose.

Fourteen Albemarles carrying Company C and the pathfinders took off from RAF Harwell starting at 2308 hours on June 5. Another 36 Dakotas with the remainder of 1 CAN PARA BN aboard departed Down Ampey airfield around 2320 hours, all en route to Dropping Zone “V” on the outskirts of Varaville. Inside one Dakota, Sergeant Harry Reid pondered his situation. “I was engrossed in my own thoughts, mostly about what was to come this night. It was hard to believe we were really on our way to fight…. I wondered how many of us might not make it back and how I would behave under fire.”

The chaos that Brigadier Hill predicted did not take long to appear. “As we crossed the beach all hell broke loose,” remembered Corporal G.H. Neal of Company A. “ I was standing in the doorway when a solid wall of tracer bullets came up to meet us. Heavier ack-ack shells were exploding around us and the plane was jumping with each explosion.”

John Ross of Company C jumped from an Albemarle. “When the green light came on, the first man threw out a bicycle or some other piece of equipment with its own parachute, then he brought his knees together and was gone. He was quickly followed by nine others.”

Ross’s group made an accurate jump. “Our plane was one of only four, I think, that dropped us right on the drop zone. Most other planes were scattered all over Normandy. I personally landed almost exactly where I was supposed to land.”

This bit of good luck was the last Company C would enjoy for a while. The British pathfinders landing with Ross discovered the Eureka radio transmitters they were supposed to place on DZ “V” had mostly been shattered on landing. Many of the beacon lamps intended to light the way for following waves of transports were also lost or inoperative. Worse, huge clouds of dust raised by an ongoing RAF bombing mission almost completely obscured the drop zone.

Heavy antiaircraft fire forced many transport pilots to take evasive action. Yet their sharp maneuvers made it even more difficult for navigators to find the DZ, as well as tossing the anxious paratroopers around like pinballs inside their planes. Bill Lovatt, a 19-year-old private, remembered, “As I approached the door I was flung back violently to the opposite side of the aircraft in a tangle of arms and legs.” Somehow, Lovatt made a successful jump.

To escape the flak, some pilots sped up. “The plane was going much too fast,” said Captain John Simpson. “When I went out the prop blast tore all my equipment off…. All I had was my clothes and my .45 revolver with some ammo.” Indeed, over 70 percent of the battalion’s communications gear, support weapons, and equipment bundles were never recovered. Many troopers also lost their leg bags, which were ripped away during the jump.

Private Jan de Vries landed far from his intended DZ. “I wondered where the heck I was when I hit the ground,” he later recalled. “I spent all night trying to find my way in the dark toward my rendezvous point near the coast, dodging enemy patrols the whole way.”

Several planeloads of jumpers came down in marshes or flooded zones. “Looking out of the plane it looked like pasture below us, but … I landed in water,” remembered Private Doug Morrison. “The Germans had flooded the area a while back and there was a green algae on the water so it actually looked like pasture at night from the air.”

The battalion commander also made a water landing. “I personally was dropped a couple of miles away from the drop zone in a marsh near the River Dives,” Lt. Col. Bradbrooke stated, “and arrived at the rendezvous about one and a half hours late and completely soaked.”

The jump had been a disaster. Fully half the battalion’s officers were lost, dead, or captured; the fate of Operation Neptune might well hinge on those still able to follow orders. Their years of training now began to pay off. Individually or in small groups, the soldiers of 1 CAN PARA BN got moving. They had work to do.

Major Murray MacLeod was supposed to have more than 100 men from Company C assembled on DZ “V” for the Varaville attack. Instead, a mere 15 Canadian paras were on hand when the aggressive officer began his assault at 0030 hours. MacLeod could not tarry. The main drop was due to occur at any time, and a German position at the Chateau de Varaville threatened the entire area. It had to be eliminated.

After collecting another five troopers along the way, Major MacLeod positioned half his force to provide covering fire while he led the rest up into an abandoned gatehouse. From there MacLeod could observe an elaborate defensive position, complete with a 75mm gun, in the Chateau’s courtyard. He estimated there were at least 100 German soldiers facing his 20 Canadians.

The enemy announced its presence by putting a 75mm round through the gatehouse roof. MacLeod’s men returned fire with a PIAT antitank launcher, which missed. The Germans’ next high-explosive shell was more accurate, though, killing three paras outright while mortally wounding the major.

Captain John P. Hanson, company executive officer, took over and settled the men in for a siege. By daybreak another 15 misdropped paras had trickled in, adding their two-inch mortar and Bren guns to the fight. Well-trained Canadian riflemen began taking a deadly toll on their foes—at 1000 hours the Germans lost heart. Some 43 enemy soldiers came out under a white flag of surrender, and 1 CAN PARA BN’s primary D-Day objective had been achieved.

Back on DZ “V,” Lieutenant John A. Clancy of Company A could wait no longer. At 0600 hours the young platoon leader gathered everyone he could find—21 men in all—and headed out for the Merville Battery. Earlier that morning 150 soldiers from 9 PARA BN had successfully stormed that fortification, albeit with heavy losses. Clancy’s men arrived in time to help their British comrades care for the wounded before escorting 9 PARA’s survivors to an assembly area. The Canadians then moved out to join their parent battalion at the le Mesnil crossroads.

John Kemp, a sergeant with Company B, narrowly missed landing in the Dives River following his early morning jump. Pausing to gather a few mates, Kemp struck out for his objective at Robehomme. “Everybody got together pretty quickly,” he remembered, “and on our way to the bridge we heard a bicycle bell ringing. We had some French-Canadians in our battalion, and we managed to bring down this bicycle rider who turned out to be a girl, and we found out from her where the Robehomme Bridge was. As a matter of fact, she led us to the bridge.”

Eventually, 30 Canadians converged on Robehomme. With Major Clayton Fuller in command, they dug in and awaited the arrival of some British sappers who were supposed to help blow the span. By 0300 hours, Fuller could stand by no longer. Collecting all the paras’ high explosives, a team of men under Lieutenant Norman Toseland set off a charge that weakened but did not collapse the structure. Fortunately, a detail of airborne engineers showed up shortly thereafter to finish the job.

It was now past dawn, and Major Fuller could observe many well-armed enemy soldiers blocking his route to the battalion rendezvous at le Mesnil. Rather than risk the annihilation of his small force, Fuller chose to hide out during daytime and move overland only after nightfall. Picking up stragglers from several 6 AB DIV units along the way, Company B finally reached its destination at 0330 hours on June 8.

Meanwhile, the machine gunners, mortarmen, and signalers of Headquarters Company assembled on the le Mesnil crossroads. With most of their Vickers guns, mortars, and radios lost or damaged, these soldiers were pressed into duty as riflemen by Lt. Col. Bradbrooke. Officers urgently directed newly arriving troopers into the battalion’s growing but still tentative defensive line.

Bradbrooke knew his men had successfully accomplished all their D-Day missions but were now entering a dangerous phase of the operation. Lacking heavy weapons and reliable radio communications, 1 CAN PARA BN was especially vulnerable to an enemy counterattack—something for which the Germans were notorious. Every moment spent preparing battle positions would pay benefits for the Canadians once their foe began striking back.

Fortunately, the terrain around le Mesnil was well suited for defensive operations. Dense hedgerows—bocage country—restricted an attacker’s mobility while offering ready-made cover for dug-in defenders. A small group of aggressive fighting men could effectively stymie even large-scale assaults providing they were led well and resupplied on a regular basis.

The dreaded German counterattack finally came on June 7. After infantry probes fixed the Canadians’ location, artillery and mortar barrages began pouring down relentlessly. “We were shelled for 12 hours straight,” remembered Private Mervin Jones. “No one was hurt, but it was sure hard on the nerves.”

Apart from the shellfire, German snipers also exacted a heavy toll on 1 CAN PARA BN. They specifically targeted leaders, as John Kemp recalled. “I was the fifth to take over as the Company Sergeant-Major,” he said, explaining how enemy sharpshooters looked for men wearing sergeants’ stripes. “It got so we didn’t wear ranks anymore.”

The Canadians maintained an active defense, though, using their night-fighting skills to stealthily infiltrate behind the lines and gain information on enemy locations, activity, and plans. These reconnaissance missions kept the foe off balance but held many dangers for those paras performing them. Sergeant Bill Dunnett compared the fighting around le Mesnil to “men hunting [each other] through the woods and narrow lanes” of the bocage.

Paratroopers endured daily artillery barrages, constant sniper activity, and occasional enemy probes. Taken together with short rations, limited drinking water, and an unnaturally warm Norman summer that caused unburied bodies to rapidly decompose, the Canadians’ endurance was sorely tested. “Many of our people became beat, really beat,” said Lieutenant John Madden. “I remember shaking sentries awake I don’t know how many times.” But the paras held firm.

While enemy forces could not break through at le Mesnil, they did discover a seam in the Allied defenses farther north near Bréville. On June 10, German troops seized this village, splitting open 6 AB DIV’s position on Bavent Ridge. Recognizing the threat this breakthrough posed to his division, Maj. Gen. Gale pushed reinforcements forward to retake Bréville. For two days British infantry, supported by tanks, tried and failed to plug this dangerous gap in the lines.

The situation worsened when a massive enemy counterattack stormed out of Bréville on the afternoon of June 12. Hammered by assaulting infantry and armor, Gale’s men wavered and then broke. Brigadier Hill, observing this crisis, called on his trusted Canadians to help shore up the British defenses. “Come on chaps, nothing to worry about,” the doughty Hill said as he personally led 40 paras forward against the advancing foe.

By nightfall, 6 AB DIV had recaptured Bréville. The scratch force from 1 CAN PARA BN had done its part, often fighting hand to hand until the Germans were repulsed. Their improbable victory came at heavy cost, however. Only 20 soldiers—half of those who set out with Brigadier Hill—returned to le Mesnil with him that evening.

The Canadians remained in place until June 17, when they briefly came off the line for a badly needed breather. Eight days later the paras were back at le Mesnil, where near constant fighting marked their summer. Enemy artillery, snipers, and booby traps continued to pick men off, and while replacements did arrive in July it was a tired, undermanned battalion that led the Normandy breakout in August. Not until September 4 was 1 CAN PARA BN brought back to England for rest, refitting, and training in preparation for its next operation.

Casualties were severe. During its time in France, the battalion suffered 25 officers and 332 other ranks killed, wounded, or missing. On D-Day alone, 1 CAN PARA BN lost three officers and 18 enlisted men killed or died of wounds, one officer and eight men injured, and three officers plus 83 other ranks captured. Of 541 paras who made the jump into Normandy, only 197 returned unhurt to England that September.

The Canadians saw infantry service in the Ardennes before making another combat jump in March 1945 as part of Operation Varsity, the airborne crossing of the Rhine River. They advanced far into Germany, meeting Russian troops at war’s end, and were among the first of Canada’s forces to be repatriated after V-E Day. Though their battalion was deactivated shortly thereafter, those who served with this elite organization could take great pride in its unrivaled record of mission success.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, writing after the war, summed up the unique combination of aggressiveness, initiative, and expertise exhibited by the soldiers of 1 CAN PARA BN. “They are firstly all volunteers and are toughened by physical training,” Montgomery wrote. “They have ‘jumped’ from the air and by doing so have conquered fear…. They have the highest standards in all things, whether it be skill in battle or smartness in the execution of all peacetime duties. They are in fact men apart—every man an emperor.”

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer who has earned both the United States and Canadian Forces parachutist badges. He writes from his home in Scotia, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments