By Michael E. Haskew

On May 2, 1942, the eve of the Battle of the Coral Sea, a Consolidated PBY-5A Catalina flying boat skimmed the water’s surface and touched down in the lagoon of Midway Atoll, 1,137 miles west of Oahu. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, had come to inspect the preparations for the defense of the atoll—and he had given little notice of his impending visit.

Preparations for the defense of Midway against a probable Japanese assault had been underway for about two years, and a sense of urgency prompted Nimitz to see the progress for himself. The admiral greeted U.S. Navy Commander Cyril Simard, overall commander at Midway, and Lt. Col. Harold D. Shannon, commander of the 6th Marine Defense Battalion and other assigned ground troops. Nimitz inspected the prepared defensive positions and the barbed wire that glinted in the sun, wreathing the beaches of the atoll’s two islets, Sand and Eastern. He informed the officers that they could expect a Japanese attack at the end of the month and followed up with a pointed question. What else did the defenders of Midway need to repel a major enemy landing?

Shannon produced a list of the men and equipment. Nimitz looked him in the eye and asked a pointed question: “If I get you all these things you say you need, then can you hold Midway against a major amphibious assault?”

Shannon did not hesitate and replied, “Yes, sir!”

Maintaining control of Midway was the key to American victory in the Pacific. The fall of the Philippines was imminent, and after the Japanese had taken Wake Island and Guam, Midway became the westernmost American outpost in the Central Pacific. In 1938, a survey presented to the U.S. Congress and titled the Hepburn Report had identified Midway as second only to Pearl Harbor in importance to American security in the Pacific. The atoll stretches only about six miles across and consists of Sand and Eastern islets, a coral reef, and a shallow lagoon. A U.S. possession since 1867, it had been developed slowly through the years.

In 1903, the Commercial Pacific Cable Company established a station on Sand Island. Pan American Airways built a seaplane base there in 1935 to service its China Clipper flying boat. Still, Midway remained a remote, quiet speck in the immense Pacific; its most famous inhabitants were large, ungainly albatrosses, or gooney birds. By the late 1930s, the prospect of war with Japan changed all that.

On December 20, 1939, Admiral Harold Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, ordered the establishment of a Marine garrison on the atoll. Elements of the 3rd Defense Battalion were there initially, and then followed by the 1st Defense Battalion and the 6th Defense Battalion. Eventually the Midway contingent came to be formally known as the Midway Detachment, Fleet Marine Force. Construction of a naval air station was begun in the spring of 1940, and the project was completed in August 1941.

At 6:30 am on December 7, 1941, news of the Pearl Harbor attack flashed from Oahu. The Midway garrison went on high alert. At dusk that evening, a lookout spotted a blinking light southwest of Sand Island. Two Japanese destroyers, the Akebono and Ushio, were maneuvering offshore.

At 9:35 pm, the first Japanese 5-inch shells fell. The Marines responded with 3-inch and 5-inch guns. Japanese shells set the large seaplane hangar afire. Another round scored a direct hit on an air intake on the concrete housing of the Sand Island powerplant. The blast wounded 1st Lieutenant George H. Cannon, who refused to be evacuated until communications were reestablished and the damage assessed. Cannon later died and received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Midway gunners and subsequent reports suggested that the Marines had hit one of the destroyers, starting fires aboard the vessel, but the damage was never confirmed. The half-hour duel left two Marines dead and 10 wounded. Two sailors at the naval air station were also killed.

Within days of the first encounter with the Japanese, the garrison on Midway grew steadily. On December 17, 17 Vought SB2U Vindicator dive bombers of Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 231 (VMSB-231) arrived from Hawaii. The 5-inch seacoast guns of Batteries A and C, 4th Defense Battalion came ashore at mid-month along with additional 3-inch guns and old seven-inch weapons. Hours later, 14 obsolete F2A-3 Brewster Buffalo fighters, the vanguard of Marine Fighter Squadron 221 (VMF-221) originally intended to reinforce Wake Island, landed at Midway. On the day after Christmas, the seaplane tender USS Tangier brought the 5-inch guns of Battery B, 4th Defense Battalion to Midway along with 12 antiaircraft machine guns from the battalion’s special weapons group.

Nimitz was true to his word, and within days of his visit three additional 3-inch antiaircraft batteries, a 37mm antiaircraft battery, and a 20mm antiaircraft battery of the 3rd Defense Battalion stationed at Pearl Harbor were assigned temporarily to Midway. In addition, a platoon of five light tanks and two rifle companies of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion were sent to bolster Shannon’s infantry command. The Midway air component, designated Marine Air Group 22 (MAG-22), under Lt. Col. Ira Kimes, was augmented with 16 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers and seven new Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters.

Meanwhile, Simard and Shannon were promoted to the ranks of captain and colonel respectively and were notified that the date for an expected Japanese invasion was revised to the first week of June, allowing a few more days of preparation.

By then, Midway was defended by 3,652 men of the 6th Marine Defense Battalion supplemented by elements of the 3rd Marine Defense Battalion and the two companies of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion. Its air group included six operational Wildcat and 21 Buffalo fighters of VMF-221 commanded by Major Floyd B. “Red” Parks, and the 18 Dauntlesses and 21 Vindicators of VMSB-241 (the squadron had split and been renamed) under Major Lofton R. Henderson. Lieutenant Colonel Walter Sweeney led a flight of 15 Army Air Corps four-engine Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. Four Army Martin B-26 Marauder bombers modified to carry torpedoes, six brand new Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers, and 29 long-range Consolidated PBY and PBY-5A Catalina patrol planes rounded out the hodgepodge of aircraft.

Just a week after Admiral Nimitz visited the atoll, Japanese territorial ambitions in the Pacific experienced their first major setback at the Battle of the Coral Sea. An invasion force sent to take Port Moresby at the southeastern tip of the island of New Guinea had turned back after American and Japanese aircraft clashed in the first naval battle in history in which the opposing surface ships never sighted one another.

The fleet carrier Lexington had been sunk and the carrier Yorktown seriously damaged. The Japanese light carrier Shoho was sunk, but more troubling to the Imperial Navy were the temporary loss of the 26,000-ton fleet carrier Shokaku, which had taken three bomb hits and would be out of action for several months, and her sister Zuikaku, which had sustained such heavy losses to her air group that the lack of available planes and trained pilots kept that carrier out of action temporarily.

Despite the disappointment at Coral Sea, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet, chose to maintain the initiative with the seizure of Midway. A Japanese victory was expected to achieve three key strategic objectives. The defensive perimeter of the empire would be expanded, improving security. The threat to Hawaii would intensify. The Americans would be compelled to fight for Midway, committing their precious carriers to the effort, and the battle would result in their destruction.

Considerable uncertainty existed among the Americans as to exactly where the next enemy blow would fall. The intelligence coup that gave Nimitz the valuable knowledge that the target was Midway came from a somewhat remarkable source. At Station Hypo on Oahu, Lieutenant Commander Joseph J. Rochefort ran the crew of cryptanalysts that had succeeded in cracking much of JN-25B, the Japanese Navy operations code. Although a change in the code had been approved, delays kept JN-25B in common use prior to Midway, and Rochefort’s people were soon reading up to 85 percent of Japanese radio communication.

As the clock ticked toward a showdown at Midway, Nimitz had been in command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet for only five months. A Texan, he possessed the even temperament and quiet optimism that were critically needed at such a desperate hour. He was also aggressive to the extent that he felt it was absolutely necessary to fight the Japanese as soon as conditions were reasonably favorable.

While the Japanese possessed a substantial quantitative edge in aircraft carriers, other warships, and planes, two factors weighed on Nimitz’s decision to commit to a fight for Midway. The atoll was of such strategic value that it had to be defended, and Rochefort’s intelligence triumph offered the element of surprise, a significant equalizer against a superior force.

The crippled Yorktown limped into Pearl Harbor after Coral Sea, and early estimates indicated that the damage would take weeks to repair. Nimitz had two operational carriers, Enterprise and Hornet. The availability of a third was critical to any hope of victory. He ordered work to begin immediately aboard Yorktown and ordered that the carrier be battleworthy within 72 hours. Workmen swarmed aboard and performed something of a miracle in accomplishing the task.

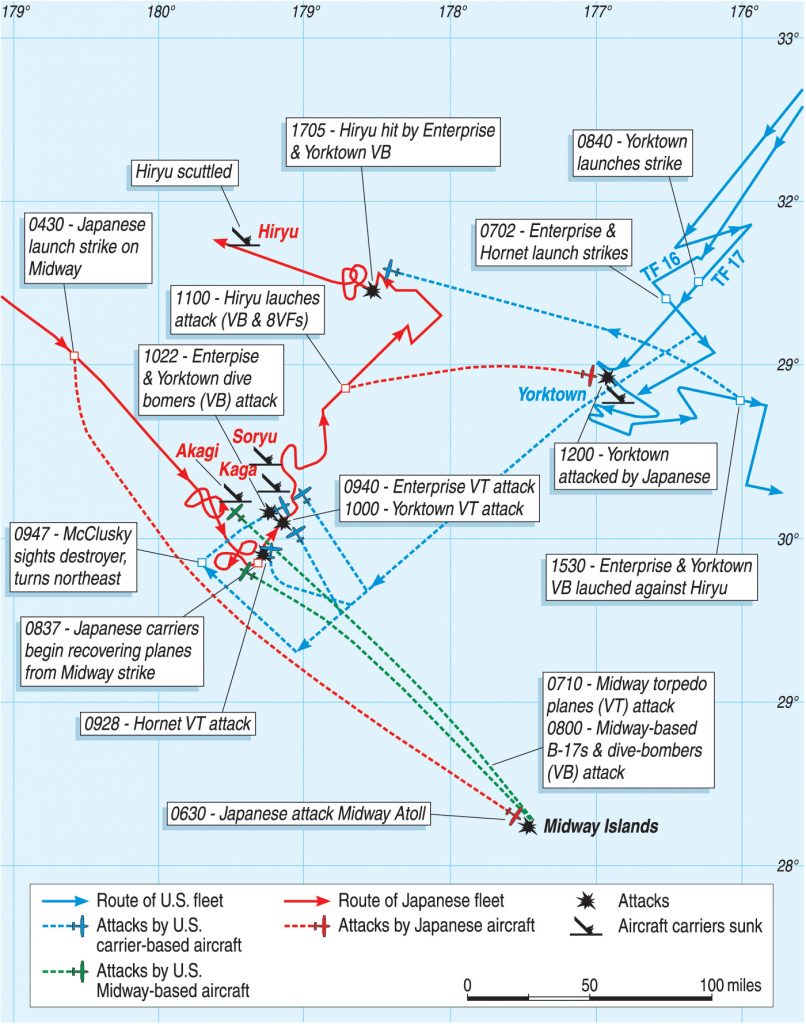

Nimitz ordered two task forces to rendezvous 325 miles northeast of Midway at a location appropriately named Point Luck. From there, they would hopefully maintain the element of surprise and attack the Japanese carriers while their planes were engaged in softening up Midway in preparation for the landing of 5,000 troops.

Task Force 16 included Hornet and Enterprise, five heavy cruisers, a single light cruiser, and nine destroyers under Admiral Raymond A. Spruance in his first carrier command since Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey was hospitalized with severe dermatitis. Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s Task Force 17 included Yorktown, two cruisers, and six destroyers.

Yamamoto’s tendency for complex planning was evident with the Midway operation. Offensive action would begin on June 3 with an air raid on the U.S. base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands far to the north. The Americans would either rush northward to defend Alaskan territory or remain at Pearl Harbor. In either case, Yamamoto did not expect much opposition to the capture of Midway. He believed that two American carriers had been sunk at Coral Sea and that American air power had been substantially weakened.

Yamamoto believed Nimitz would be slow to respond, and when the American admiral did that it would be too late. Japanese Marines would already have occupied Midway. The naval forces involved in the Aleutian thrust would be positioned to intercept any move northward, while the warships covering the Midway landings could assert their overwhelming strength. Their aircraft would sink any American ships within range, while the big guns of their battleships and cruisers would finish off any survivors in a potential surface action.

Historian Samuel Eliot Morison commented on Yamamoto’s Midway blueprint. “The vital defect in this sort of plan,” he wrote, “is that it depends on the enemy’s doing exactly what is expected. If he is smart enough to do something different—in this case to have fast carriers on the spot—the operation is thrown into confusion.”

Nevertheless, Yamamoto’s naval power was formidable. No fewer than eight carriers, 11 battleships, 20 cruisers, 60 destroyers, and 15 submarines, along with transports and other support vessels were involved.

The Japanese commander divided his forces into numerous major components, some of which were subdivided into smaller units with specific tasks. In the absence of Shokaku and Zuikaku, the heart of the fleet consisted of four of the six aircraft carriers of the Kido Butai, or Striking Force, that had attacked Pearl Harbor the previous December. Under the command of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, these were the flagship Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu. The carriers were accompanied by two battleships, three cruisers, and 11 destroyers.

The Japanese Main Body included three new battleships, a light carrier, a cruiser, and eight destroyers. Yamamoto assumed overall command aboard the super battleship Yamato, displacing more than 68,000 tons with a main armament of massive 18.1-inch guns. The Guard Force, under Admiral Takasu Shiro, sailed with Yamamoto to take up station to support the Aleutian forces if necessary with four battleships, two cruisers, and 12 destroyers. The Midway Invasion Force, commanded by Admiral Nobutake Kondo, included a carrier, troop transports, and battleships and cruisers for fire support. The Northern Force, under Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya, included two carriers, three cruisers, and the troops that would occupy Attu and Kiska. A cordon of submarines, intended to detect the departure of any U.S. ships from Pearl Harbor, arrived too late to catch either American task force.

On May 27, Navy Day for the Combined Fleet, Yamamoto’s Main Body and the Kido Butai under Nagumo sailed from their anchorage at Hashirajima, in the Inland Sea south of the naval base at Kure and the city of Hiroshima. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, the naval aviator who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor, was aboard Akagi. The most accomplished air leader in the Japanese Navy, Fuchida was in the carrier’s sick bay with appendicitis for much of the encounter. Commander Minoru Genda, planner of the tactical element of the Pearl Harbor attack, was aboard Akagi but suffering from pneumonia. His contribution as the Midway battle developed was greatly diminished.

The four carriers of Nagumo’s striking force mustered more than 240 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, Aichi D3A1 Val dive bombers, and Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bombers. Aboard the three American carriers was a roughly equivalent number of Wildcat fighters, Dauntless dive bombers, and Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bombers.

At 3 am on June 3, the pilots of the 22 Midway-based Catalinas detailed to fly reconnaissance missions in search of the approaching Japanese were roused from their bunks. Little more than an hour later, they were airborne. The pilots were assigned search areas of 700 miles, arcing from the atoll like the hands of a clock and covering thousands of square miles of ocean.

For several hours, nothing was visible but the expanse of an empty Pacific. Then, as the Catalinas reached the limits of their range that morning, Ensign Charles R. Eaton and his crew spotted several Japanese ships and radioed the first confirmed sighting of the enemy during the Battle of Midway: “Two Japanese cargo vessels sighted bearing 247 degrees, distance 470 miles. Fired upon by AA.”

Minutes later, the PBY piloted by Ensign Jack Reid, already extending the outward leg of its search, was about to turn for home when three men almost simultaneously spotted the wakes and dim silhouettes of Japanese ships. Reid dashed off a somewhat cryptic message: “Sighted Main Body.” This was quickly followed by “Bearing 262, distance 700.”

Back at Midway, Captain Simard asked for ship types, course, and speed. Reid turned and trailed the Japanese. After an agonizing interval, Reid confirmed 11 ships, including a small aircraft carrier, a seaplane carrier, two battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. The ships below were the battleships and cruisers of the Midway Invasion Force under Admiral Kondo. Eaton had discovered the Minesweeper Group, also a part of the Invasion Force.

Until the exhilarating moment that the enemy was sighted, the Americans defending Midway had been in the dark as to what was unfolding around them. They were under no illusions that further reinforcements were coming. If Midway’s radar detected an incoming Japanese air raid, the fighter pilots would rise to meet them. If an invasion force appeared offshore, the ground troops would repel the enemy on the beaches. If an opportunity presented itself to strike a blow against the enemy ships, the bomber pilots would attack. For days, there had been nothing to do but work, watch, and wait.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert C. McGlashan, the operations officer of the 6th Defense Battalion at Midway, remembered the evening prior the arrival of Japanese planes above Midway. “Of course, there were a thousand things more that could have been done; but all the essential things had been done—and not a day to spare. As I turned in that night knowing that the Japs would arrive by morning, I felt that, come what may, we had done all we could.”

Meanwhile, the Japanese had already struck the first blow of the battle as 14 bombers and three fighters attacked Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians in the early morning hours of June 3, destroying a barracks, fuel tank farm, and other installations and killing 25 Americans.

Suddenly, the waiting was over at Midway. Captain Simard and Colonel Shannon knew that within hours they would probably be under air attack—and after the enemy planes softened up Midway’s defenses a Japanese amphibious assault would follow. The American air group swung into action. At approximately 12:30 pm, nine B-17s of the 431st Bombardment Squadron took off to attack the Japanese. About four hours later, the big bombers spotted the Japanese Transport Group, under Admiral Raizo Tanaka, dropped their 600-pound bombs from altitudes of 8,000 feet or more, and headed home. Reports of hits proved inaccurate. No casualties were sustained on either side, but the Japanese knew that they had been discovered.

At 1:30 am on June 4, three of Midway’s Catalinas armed with torpedoes attacked the Transport Group again. This time, one put a torpedo into the tanker Akebono Maru, killing or wounding 23 Japanese sailors.

Nagumo was still unaware that three American aircraft carriers were in the vicinity of Midway and had turned to the northwest, the most likely approach route of the Japanese carriers if they were intent on launching air strikes against Midway. He turned his own carriers into the wind and began doing just that. A successful raid would render the atoll’s airstrip useless, eliminate the threat of further air attacks from Midway, and pummel its defenses in preparation for the amphibious landing.

As Sweeney’s B-17s were taking off before dawn to renew their attacks on Tanaka, 108 Vals, Kates, and Zeros rose from the decks of the Japanese carriers under the command of Lieutenant Joichi Tomonaga, a veteran pilot from the Hiryu replacing Fuchida as strike leader. These aircraft carried high-explosive bombs, and Nagumo retained roughly half his aircraft armed with torpedoes to meet the threat of any American surface ships.

At 5:20 am, Midway reconnaissance again hit paydirt as Lieutenant Howard F. Ady reported sighting a Japanese aircraft carrier and followed that with a report that enemy aircraft were approaching the atoll. Another search plane, piloted by Lieutenant (j.g.) William A. Chase, spotted the inbound Japanese raid at 5:45 and radioed in plain language, “Many planes heading Midway, bearing 320 degrees, distance 150.”

The B-17s were redirected to attack the carriers rather than the landing force, and within minutes Midway’s antiaircraft defenses were on the alert. Every aircraft, its pilot already in the cockpit and its engine running, was sent aloft. Midway radar picked up the Japanese 93 miles out.

Flying at 14,000 feet about 30 miles from Midway, the pilots of VMF-221 spotted a large number of Vals flying in V-formations with Zeros buzzing around them. Major Parks’ fighters were divided into two groups. Flying a Buffalo, Parks led the first group of eight F2As and five Wildcats. The second group, under the command of Captain Kirk Armistead, consisted of 12 Buffalo fighters and a single Wildcat. Parks led his fighters directly into the Japanese formations, while Armistead’s group flew slightly to the west, acting as a reserve.

Captain John F. Carey, flying a Wildcat, shouted “Tally-ho!” and screamed down on the enemy bombers followed by his wingmen, Captain Marion E. Carl and 2nd Lt. Clayton M. Canfield. Carl and several other pilots engaged in a swirling dogfight with the Zeros. The Americans were astounded by the agility of the enemy fighters. In his after-action report, one VMF-221 pilot remarked, “I saw two Brewsters trying to fight the Zeros. One was shot down, and the other was saved by ground fire covering his tail. Both looked like they were tied to a string while the Zeros made passes at them. I believe that our men with planes even half as good as the Zeros would have stopped the raid completely.”

Carey and Canfield slashed through the Japanese bombers, but little is actually known of the results. The single firing pass was probably followed by a brief but desperate fight with the Zeros. Parks was shot down and killed. Only three pilots of his group survived. Within 10 minutes, Armistead’s fighters were in the thick of the unequal struggle.

“At about 0620, I heard Captain Carey transmit ‘Tally-ho’ followed by ‘Hawks at angels 14, supported by fighters.’ I then started climbing and sighted the enemy at approximately 14,000 feet at a distance of five to seven miles out, and approximately two miles to my right,” wrote Armistead, who survived the melee. “I immediately turned to a heading of about 70 degrees and continued to climb. I was endeavoring to get a position above and ahead of the enemy and come down out of the sun. However, I was unable to reach this point in time. I was at 17,000 feet when I started my attack. The target consisted of five divisions of from five to nine planes each, flying in division V’s … I was followed in column by five F2A-3 fighters and one F4F-3 fighter, pilot unknown. I made a head-on approach from above at a steep angle and at very high speed on the fourth enemy division, which consisted of five planes. I saw my incendiary bullets travel from a point in front of the leader, up through his plane and back through the planes on the left wing of the V. I continued in my dive, and looking back, saw two or three of those planes falling in flames …

“After my pullout,” Armistead continued, “I zoomed back to an altitude of 14,000 feet; at this time I noticed another group of the same type bombers following along in their path. I looked back over my shoulder and about 2,000 feet below and behind me I saw three fighters in column, climbing up toward me, which I assumed to be planes of my division. However, they climbed at a very high rate, and a very steep path. When the nearest plane was about 500 feet below and behind me I realized that it was a Japanese Zero fighter. I kicked over in a violent split S and received three 20mm shells, one in the right wing gun, one in the right wing root tank, and one in the top left side of the engine cowling. I also received about twenty 7.7mm rounds in the left aileron, which mangled the tab on the aileron and sawed off a portion of the aileron. I continued in a vertical dive at full throttle, corkscrewing to my left, due to the effect of the damaged aileron. At about 3,000 feet, I started to pull out and managed to hold the plane level at an altitude of 500 feet.”

During the sharp aerial battle, 24 American fighters were either shot down or seriously damaged. The pilots of VMF-221 fought bravely but could not turn back the Japanese onslaught.

The Japanese aircraft flew relentlessly on, and at 6:30 am, Colonel Shannon barked, “Open fire when targets are in range.” One minute later, Sand and Eastern islands erupted.

Tomonaga led his planes into withering fire from Midway. Bombs destroyed the seaplane hangar, and the fuel dump 500 yards to the north was in flames. The freshwater processing facility was blasted, and two bombs destroyed the powerhouse on Eastern Island. Major William Benson, in charge of the 6th Defense Battalion’s Eastern Island command post, was killed when a direct hit demolished the position. Twenty-four Americans were killed and 18 wounded.

However, the Japanese paid a substantial price as 11 attacking planes were either shot down or failed to return to their carriers and more than 40 were damaged, some beyond repair. The Marine antiaircraft fire had been so accurate that it disrupted the attempts to crater the airstrip. Only a couple of small holes had been made, and it remained functional. Tomonaga radioed that a second strike was necessary.

When the Japanese planes were gone, the Midway air controller sent a message: “Fighters land. Refuel by divisions, 5th Division first.” The only response was a crackle of dead air. The message went out several times, and finally a general recall was broadcast. With “All fighters land and reservice,” only 10 VMF-221 planes came in. Of these just two remained airworthy.

Ady’s sighting of a lone Japanese carrier had fixed the enemy’s location for Fletcher and Spruance while also alerting Midway of the Striking Force’s presence. Lieutenant Colonel Kimes threw every available Midway-based aircraft at Nagumo’s carriers. More than 50 planes without fighter escort mounted no fewer than five separate attacks against Nagumo’s warships during a roughly 90-minute period from 7:05 am to just after 8:30.

Captain James F. Collins led the four Army Air Corps Marauders, which mounted attacks on the Japanese carriers almost simultaneously with the six Navy TBF Avengers under Lieutenant Langdon K. Fieberling. No hits were scored.

These were followed less than an hour later by the 16 Marine Corps Dauntless dive bombers of VMSB-241. At 7:55 am, Major Henderson ordered, “Attack two enemy CV on port bow!” Most of the Dauntless pilots were inexperienced, and Henderson elected a glide bombing run rather than a steep dive-bombing attack. Zeros pounced on the squadron commander, whose plane was seen spiraling into the sea with one wing afire.

Captain Richard E. Fleming took command of the squadron, and the pilots pressed home their attacks with great courage. A pair of bombs bracketed the Hiryu, and three more exploded near the stern of the Kaga, cascading water and steel fragments across the fantail. However, no direct hits were achieved. Fleming was reported to have killed or wounded several Japanese sailors in a strafing run across the flight deck of the Hiryu, which was emblazoned with a large rising sun emblem. Half the Dauntlesses were lost during the raid, and of the eight that returned to Midway two were shot to pieces, unfit for further service.

A few minutes later, Lt. Col. Sweeney led his B-17s, diverted from their original target of Tanaka’s transports, in a high-level attack from 20,000 feet. The bristling .50-caliber machine guns of the B-17s and their extreme altitude kept the Zeros at a distance, but the Japanese ships took no hits.

Around 8:20 am, 11 lumbering VMSB-241 Vindicators led by Major Benjamin W. Norris found the Japanese carriers. Norris knew the Zeros were likely to slaughter his old dive bombers and observed that the Japanese escort ships were putting up a curtain of antiaircraft fire. He elected to attack the closest targets, the enemy battleships. Near misses rocked the Haruna, and one American bomb narrowly missed the fantail of the Kirishima, but not a single hit was scored.

At least 19 American planes were shot down during the raids by Midway’s aircraft, while three Zeros were downed. However, the gallant attacks were not in vain. The Marine, Army, and Navy pilots had stretched the Japanese combat air patrol nearly to the limits of their endurance. More Zeros had to be launched, and those in the air needed to be rearmed and refueled. It was a difficult proposition, particularly considering the larger dilemma facing Nagumo.

The Japanese commander worried that the surviving Midway-based aircraft continued to pose a threat. They had to be neutralized to capture the atoll. When he received Tomonaga’s request for a second Midway strike at about 7:15 am, he was convinced that Midway should be hit again. The Kates of the first Midway raid had been supplied by Soryu and Hiryu, while the dive bomber contingent had taken off from Akagi and Kaga. Nagumo ordered that the Kates aboard Akagi and Kaga have their torpedoes replaced with high explosive bombs. The Vals sitting on the hangar decks of Soryu and Hiryu had not yet been armed, and he ordered them equipped with high explosive bombs for land targets on Midway rather than armor piercing bombs suitable for attacks against enemy ships.

At this critical time, the failure of the Japanese to deploy sufficient numbers of reconnaissance aircraft came back to haunt Nagumo. The launching of some of the Japanese scout planes had also been delayed, and one of these, Number 4, had taken off late from the heavy cruiser Tone. As the plane reached the end of its 300-mile search radius, the pilot spotted the wakes of several ships. There was little doubt that these were American, and a message was dashed off to Tone and forwarded to Akagi: “Ten ships, apparently enemy, sighted. Bearing 010 degrees, distant 240 miles from Midway. Course 150 degrees, speed more than 20 knots. Time, 0728.”

Fuchida remembered the absolute consternation that gripped the officers aboard Akagi when the news was received. “When it reached Admiral Nagumo and his staff on Akagi’s bridge,” he wrote, “it struck them like a bolt from the blue. Until this moment no one had anticipated that an enemy force could possibly appear so soon, much less suspected that enemy ships were already in the vicinity waiting to ambush us. Now the entire picture was changed.”

At 8:20, Scout Number 4 transmitted a new warning: “Enemy force accompanied by what appears to be aircraft carrier bringing up the rear.”

The rearming of the planes for the second Midway raid would take an hour to complete. At about the same time, Tomonaga’s planes would be returning from the first Midway strike, low on fuel and some of them damaged. These planes would have to be recovered quickly. To complicate matters, the intermittent air attacks by Midway’s planes had prevented deck crews from adequately preparing to launch or recover large numbers of aircraft since their immediate concern was keeping enough Zeros of the combat air patrol aloft to fend off the attackers.

According to Fuchida, when American ships had been sighted Nagumo quickly ordered the rearming of his attack planes switched again to torpedoes and armor piercing bombs to strike the enemy naval task force. While this rearming took place, he assessed that he could recover Tomonaga’s planes as his thinly stretched combat air patrol managed to deal with any sporadic American air attacks from Midway. Once the planes of the first Midway strike were recovered, he would turn northeast, racing at 30 knots to close with the enemy carrier. He estimated that 89 planes would be available for launch at approximately 10:30 am. Time, though, was running out for Nagumo and the Striking Force.

On the evening of June 3, hours after Reid first sighted Japanese warships, Task Forces 16 and 17 had closed their distance from Midway to only 200 miles and maintained a course north of the atoll. Already alerted by Nimitz in far-off Hawaii that Reid’s sighting was not the Japanese Main Body, Fletcher and Spruance still expected the Japanese carriers to approach Midway from the northwest. Radio operators aboard Enterprise picked up Ady’s message identifying a Japanese carrier early on the morning of June 4. Moments later, another message from Chase confirmed the presence of at least one more carrier. Fletcher weighed his options.

Although Fletcher’s role at Midway has been somewhat minimized given the scope of Spruance’s triumph later on the morning of June 4, the senior admiral made a significant contribution to the American victory. At 4:30 am, about an hour before Ady’s contact was reported, the Yorktown had launched search planes to cover a 100-mile arc to the north.

At that time, Nagumo was steaming west of the American task forces, slightly more than 200 miles away and launching his first Midway air strike. Fletcher was decisive. He had to recover Yorktown’s search planes, but time was critical. Surprise might still be achieved, but the Japanese were surely looking for the Americans. At 6:07 am, just four minutes after receiving the latest report on the Japanese carriers, Fletcher ordered Spruance with Enterprise and Hornet to “proceed southwesterly and attack enemy carriers when definitely located. I will follow as soon as planes recovered.”

Fletcher intentionally gave up tactical control of the battle to Spruance, setting the stage for Spruance to make the most momentous command decision of the carrier war in the Pacific. Spruance calculated that within three hours his carriers would be approximately 100 miles distant from Nagumo—but how long could he remain undetected by the Japanese?

Aware that Japanese planes had already attacked Midway, Spruance decided to launch every available plane from Enterprise and Hornet. Launch time was 7:02 am, and the distance of about 170 miles was the extreme limit of the range of the carrier planes.

It was risky, but Spruance knew that the Japanese carriers would be required to steam toward Midway for some time to recover their planes returning from Tomonaga’s raid. If he made the right call, American planes could be positioned to attack the Japanese carriers while their decks were filled with aircraft.

Spruance became impatient due to delays and finally ordered the 37 Enterprise Dauntless dive bombers of Bombing 6 and Scouting 6 under Lieutenant Commander Clarence W. “Wade” McClusky to proceed without waiting for the torpedo bombers. The opportunity for a coordinated attack would be lost, but Spruance was also aware by 8:15 that Enterprise had picked up a Japanese scout plane’s radio message. This was the alert from Tone’s Number 4 plane that electrified Nagumo. By the time Nagumo was aware that at least one American carrier was present, Enterprise and Hornet were already launching their aircraft. When launch operations were completed, 67 dive bombers, 29 torpedo planes, and 20 fighters were in the air. Eighteen Wildcats remained on combat air patrol above Task Force 16.

Fletcher followed Spruance on a course of 240 degrees and held his planes aboard Yorktown for nearly two more hours, a wise decision should a second Japanese carrier group be spotted. By 8:40 am, Fletcher had received no new reports of Japanese activity and turned Yorktown into the wind to launch 17 dive bombers, 12 torpedo planes, and six fighters.

The last Japanese plane returning from the Midway strike landed a few minutes after 9:00 am, and Nagumo ordered his ships to execute the predetermined change of course to the northeast. The decks of the four Japanese carriers were beehives of activity, some planes being raised and lowered on elevators while others were armed and fuel lines stretched to fill empty tanks.

Nagumo’s course change did pay one dividend. The 35 Dauntlesses and 10 Wildcats of Hornet’s Bombing 8, Scouting 8, and Fighting 8 reached the anticipated point of interception and found nothing but empty ocean. Commander Stanhope Ring led the planes toward Midway in search of the enemy fleet but came up empty. The entire flight missed the battle, and several planes landed at Midway to refuel.

McClusky also flew toward the expected position of the Japanese carriers and found nothing. Low on fuel, the Enterprise air group commander chose to maintain course for another 35 miles. Rather than turning back toward Midway or his carrier, McClusky headed north at 9:35 am. Twenty minutes later, he spotted the wake of a Japanese destroyer, the Arashi, just coming off a depth charge attack on the snooping submarine USS Nautilus. McClusky figured that the speeding destroyer was hurrying to catch up with Nagumo and followed it. At 10:02, he spotted the enemy carriers 35 miles to the northeast.

Within seconds, Lieutenant Commander Maxwell F. Leslie, leading Yorktown’s Bombing 3, also made visual contact. McClusky and the Enterprise Dauntlesses were at 19,000 feet. Leslie’s Yorktown dive bombers were at 14,500. In the distance, they saw the black puffs of antiaircraft fire and streaks of flame as burning planes fell from the sky. These were the telltale signs of the valiant but futile attacks carried out by the American torpedo squadrons.

Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron led Hornet’s Torpedo 8 in the first attack against Nagumo by U.S. carrier planes. At 9:20 am, Waldron picked out the nearest Japanese carrier, Soryu, and began his run. During the next 20 minutes, all 15 Devastators of Torpedo 8 fell to Zeros. Ensign George Gay was the lone survivor among 30 naval aviators. Gay floated in the water until the following afternoon when he was picked up by a patrolling Catalina. The heroism of the men of Torpedo 8 has become legend.

Fourteen Devastators of Torpedo 6 from Enterprise, led by Lieutenant Commander Eugene E. Lindsey, pressed home attacks without fighter cover, and the Zeros slashed like wolves. In a flash, Lindsey’s and nine other American planes were shot down. Four torpedo bombers survived, probably because the Japanese pilots were so busy with new reports of incoming American planes.

At 10:00 am, Lieutenant Commander Lance E. Massey, leading Torpedo 3 from Yorktown, sighted the Japanese warships. Zeros jumped their six escorting Wildcats of Fighting 3, under Commander John S. Thach, and a wild dogfight ensued. Accounts of the battle differ as to Massey’s intended target; however, it was most likely Hiryu, which presented the best angle for a torpedo run. Five torpedoes were launched at the carrier from starboard, but no hits were scored. Torpedo 3 lost 10 of its 12 Devastators.

Forty-one American torpedo planes had attacked Nagumo’s carriers, and 35 were shot down. Of the 81 pilots and rear gunners that flew into action, 69 were killed. However, their valor was key to the drama yet to unfold. In their frantic maneuvering to avoid the attacks, the Japanese carriers had been unable to move their own aircraft to the flight decks for a strike at the American carriers or to relieve their combat air patrol. The Zeros still in the air had been heavily engaged and were critically low on fuel and ammunition. While chasing the slow Devastators they had been pulled down to the wavetops and could not regain altitude quickly enough to defend against the American dive bombers plummeting toward their carriers moments later.

Just before Massey’s ill-fated torpedo attack on Hiryu, McClusky and the Dauntlesses of Scouting 6 and Bombing 6 pushed over into steep dives, descending like avenging angels toward Kaga. Although their intent had been to split the squadrons and attack Kaga and Akagi simultaneously, a mistake in communications sent all the dive bombers hurtling toward the same target. Lieutenant Richard “Dick” Best, commander of Bombing 6, realized the error and aborted his dive along with two other VB-6 Dauntlesses. The three diverted to Akagi. At the same time, Leslie’s dive bombers from Yorktown approached Soryu from the northeast.

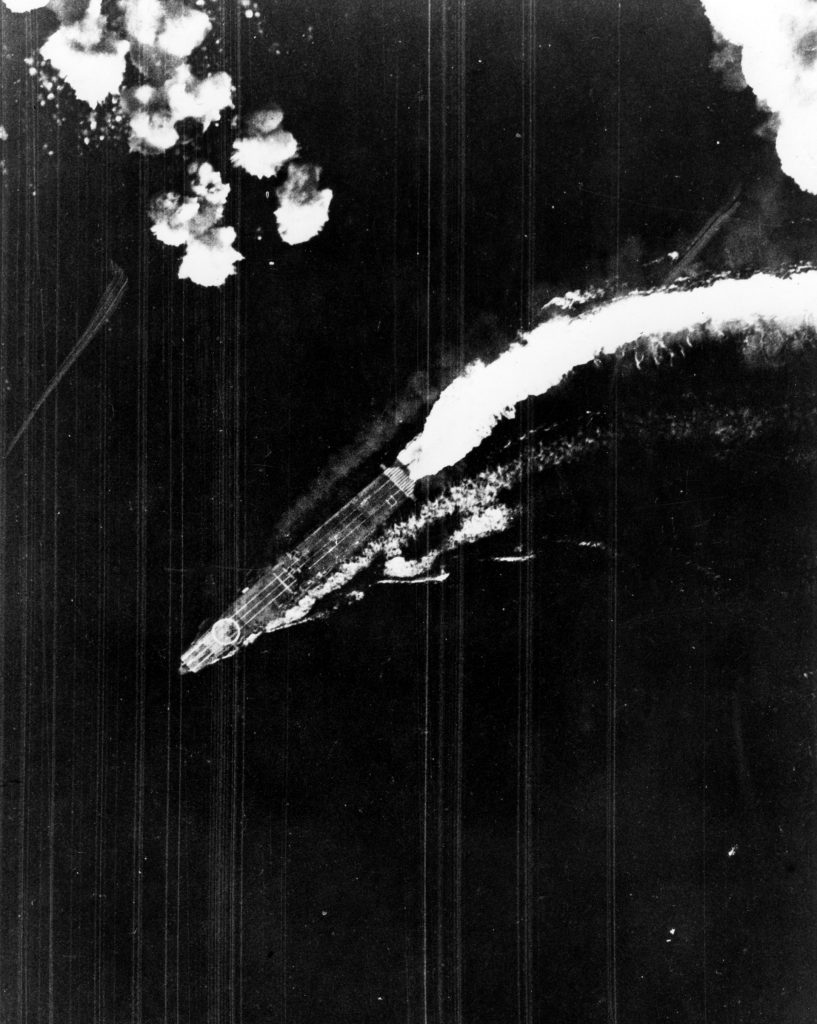

In just five minutes, the course of the war in the Pacific abruptly changed. Three Japanese aircraft carriers became flaming wreckage.

Fuchida remembered the flight deck of Akagi packed with aircraft, armed, fueled, and ready for takeoff to attack the American carriers. “The Air Officer flapped a white flag, and the first Zero fighter gathered speed and whizzed off the deck,” he wrote. “At that instant a lookout screamed: ‘Hell-divers!’ I looked up to see three black enemy planes plummeting toward our ship … The plump silhouettes of the American ‘Dauntless’ dive bombers quickly grew larger, and then a number of black objects suddenly floated eerily from their wings. Bombs! Down they came straight toward me!”

The first bomb was a near miss, its splash drenching everyone on the bridge. Best’s bomb then hit squarely on the amidships elevator and penetrated to the hangar deck. In their haste, crewmen had not secured the bombs that had been removed earlier. As these cooked off, Akagi was wracked by internal explosions. The third bomb was reported to have struck along the edge of the flight deck’s port side. Nagumo transferred his flag to the light cruiser Nagara. Fuchida broke both ankles, barely escaping with his life.

Akagi lost power and was finally abandoned at 5 pm. Yamamoto ordered destroyers to scuttle the demolished hulk the following morning. Remarkably, only 263 men were killed.

McClusky’s dive bombers screamed down on Kaga at a near 70-degree angle. Lieutenant Earl Gallaher dropped his 1,000-pound bomb on the starboard flight deck, immediately turning planes into flaming torches. Two more bombs hit near the forward elevator, igniting a gasoline truck that erupted, showering the bridge with flaming shrapnel and killing everyone present. A fourth bomb hit squarely amidships on the port side. Torpedoes from Japanese destroyers sent Kaga’s floating wreck to the bottom at 7:25 pm, and 811 men died.

When Leslie’s 17 planes attacked Soryu, only 13 of them still carried bombs. Electric arming switches had malfunctioned, and four bombs had fallen into the ocean. Leslie peppered the Soryu’s bridge with machine-gun bullets until his guns jammed. Lieutenant (j.g.) Paul “Lefty” Holmberg dropped his bomb from less than 3,000 feet and looked back at a hit amidships that exploded on the hangar deck, catapulting the forward elevator against the bridge. A second bomb smashed into the flight deck and blew a Zero into the sea as it was taking off. A third bomb struck near the aft elevator. Fires raged from bow to stern, and 20 minutes later the order was given to abandon ship. With 718 of her crew dead, Soryu drifted and finally plunged out of sight at 7:13 pm.

The American planes dodged Zeros and headed back toward their carriers; only Hiryu was left undamaged. By 10:58 am, a retaliatory strike of 18 dive bombers and six fighters was in the air, heading toward Yorktown. Led by Lieutenant Michio Kobayashi, the Vals put three bombs into the carrier. The Yorktown slowed to six knots and belched smoke, but damage control parties performed magnificently. Four hours later, the carrier was making 19 knots.

At approximately 2:30 pm, however, Tomonaga, flying a damaged Kate and aware that a ruptured fuel tank sustained during his Midway attack meant that he could not make the return flight to Hiryu, led 10 torpedo bombers against Yorktown. Two hits on the port side knocked out the boilers again. Serious flooding caused the carrier to list.

While Yorktown was under torpedo attack, word was received from one of its scout planes that Hiryu had been spotted. By 3:30, Spruance had 25 dive bombers in the air and speeding to the northwest. A half hour later, Hornet launched another 16 Dauntlesses. Yorktown damage control had been so effective that surviving Japanese pilots of the second strike from Hiryu believed they had put a second American carrier out of action. Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi aboard Hiryu issued orders to prepare five Vals, five Kates, and 10 Zeros, all that remained of the Striking Force’s once mighty air armada, to attack what he believed was the only operational American carrier left.

McClusky had been wounded earlier in the day and could not take part in the mission against Hiryu. Command of the strike that included both Enterprise planes and refugees from the Yorktown fell to Gallaher. The dive bombers achieved surprise again and hit Hiryu with four bombs on the forward section of the flight deck, one of which blew the forward elevator out of its well. Penetrating to the hangar deck, bombs destroyed the handful of planes being readied for the next Japanese mission. A sheet of flame erupted and spread rapidly throughout the ship. Hornet’s planes and B-17s from Midway attacked other Japanese ships but scored no hits.

Yamaguchi ordered the crew to abandon the Hiryu at 4:30 pm and went down with with his ship. A torpedo from a Japanese destroyer failed to finish off the blackened hulk, which drifted until just after 9 the following morning before sinking with 383 dead sailors aboard.

Despite the news that Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu were on fire, Yamamoto tried to snatch an improbable victory from devastating defeat, possibly by bringing on a night surface engagement. The situation, however, was too chaotic, and Spruance refused to bite.

After Yorktown was hit, Fletcher again deferred to his junior admiral, and it was Spruance who decided to retire eastward for several hours on the night of June 4. Although his decision was criticized in some quarters, his reasoning was sound. The Japanese had suffered shattering losses, but their surface strength was greatly superior to his own, and Midway had to be protected. By 11:30 pm, the Japanese had made no contact with American surface ships. Yamamoto cancelled the Midway operation.

That night, a report of a burning Japanese carrier reached Midway, and Major Norris led a flight of Vindicators in the direction of the sighting. The planes took off in fading light at 7:00 pm. Norris had scheduled the departure’s timing to minimize the threat of the deadly Zero fighters he had seen in action earlier. No contact with the enemy was made, and the weather worsened on the return flight. Norris’ plane was lost. He and rear gunner Pfc. Arthur Whittington were missing and presumed dead.

On the morning of June 5, Spruance and Task Force 16 waited out some bad weather and turned northwest to search for a possible fifth Japanese carrier. Several air strikes during the day produced no results.

Meanwhile, the Japanese heavy cruisers Mogami and Mikuma had been ordered to bombard Midway’s airstrip. A subsequent message then advised them to retire. During their turn, an American submarine was sighted. Mogami knifed into Mikuma, heavily damaging Mogami’s bow and slowing the cruiser to 12 knots. Mikuma stayed close to her sister. An American air strike that day produced no hits. However, the following morning dive bombers from Hornet hit Mogami with two bombs. Enterprise Dauntlesses plastered Mikuma with five bombs. Mogami took another bomb during an afternoon attack but survived. Mikuma sank that night, losing 700 crewmen.

By the evening of June 6, the U.S. Navy’s victorious task forces had withdrawn from the battle area. Yamamoto was steaming back to Japan, contemplating his apology to Emperor Hirohito and willing to accept sole responsibility for the disastrous defeat.

The American victory at Midway was decisive. The Japanese occupied the Aleutian islands of Attu and Kiska on June 7. However, they had lost the soul of their fighting force and the offensive initiative in the Pacific. Four aircraft carriers had been destroyed along with 248 aircraft. Nearly 3,100 sailors and naval aviators, the elite of the Kido Butai, had been killed.

The Americans had lost the Yorktown and the destroyer Hammann, both torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-168 on June 6, although the battered carrier remained afloat until the following day. They had also lost 144 planes and 362 dead.

Their mission, though, was accomplished. Midway was secure, and the battle that proved to be the turning point of World War II in the Pacific had been decisively won.

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History Magazine. He has been writing and editing on military topics for more than 30 years and is the author of numerous books and articles. He resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.