By James K. Swisher

Richard Hovenden of His Majesty’s British Legion Dragoons cautiously urged his tired horse through a parklike expanse of tall trees that marked the entrance to a South Carolina country crossroads junction called locally “Hannah’s Cowpens.” The predawn grayness, coupled with a raw, cold mist, sharply limited visibility, but the green-jacketed young officer could distinguish a ragged line of fringe-clad riflemen strung across the field to his front, swinging their arms vigorously and clapping their hands in an attempt to keep warm. Deployed in the frost-covered fields, breath making vapor trails in the morning air, backwoods colonial long riflemen awaited British targets. As the mist lifted, Hovenden observed the glint of gunmetal from the weapons of a mass of militia stoutly arrayed beyond the skirmish line and realized that he had located the little colonial army of General Daniel Morgan, and that the battle would be here. Dropping his reins and removing his plumed Dragoon helmet, the youthful cavalry subaltern called forward his commanding officer, Captain David Ogilvie, who, in turn, dispatched a courier for the 26-year-old chieftain of this British force, Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton.

An unlikely sequence of events precipitated this January 17, 1781, collision of two small armies at the Cowpens (whose repelling name was derived from the grassy fields whereupon Carolina farmers traditionally grazed their cattle before proceeding to market). An English privy council decision to significantly alter the overall prosecution of the American war of rebellion actually initiated the occurrence.

Facing a stalemate in the northern theater after four long years of draining warfare against numerous enemies, and failing to reach a settlement with the rebellious colonies through the Carlisle Commission, British military efforts were diverted to the Southern colonies in a vigorous attempt to sever Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina from the shaky colonial confederation. Already in possession of Savannah, Ga., Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander-in-chief, and crusty old Vice-Admiral Marriott Arbuthnot initiated a second attempt to capture Charles Town (so named until 1782), SC, an effort that succeeded in May of 1780. With this major seaport in their possession, the remainder of South Carolina was rapidly overrun by British troops and fortified bases were established throughout the state. The principal British field force under Eton-educated Lord Charles Cornwallis enjoyed a steady stream of victories in its confrontations with colonial forces save a setback on October 7, 1780, when a detached force commanded by Lt. Col. Patrick Ferguson was surrounded and its entire contingent slain or captured at Kings Mountain, SC.

American fortunes in the Southern theater were at a desperate level following the rout of its largest field army at Camden, SC, on August 16, 1780. Despite the encouraging results of the Kings Mountain victory and the inspired efforts of Francis Marion, Thomas Sumter, Andrew Pickens, and other partisan rebels, British field forces in the South seemed invincible. In October 1780, George Washington dispatched Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, among his most valued subordinates, to take command in the Carolinas. Greene had served the American commander well, initially as a divisional commander and subsequently as Quartermaster General of the Army, a position that Greene fulfilled admirably despite personal reluctance and protest. A self-educated ex-Quaker, Greene was intelligent, strategically gifted, and a capable military administrator. After his arrival near Charlotte, NC, on December 2, Greene met privately with Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, the crusty old Virginia backwoodsman who had recently been appointed to oversee militia and light troops in the Carolinas. The fortuitous assignment of this tandem of officers to conduct a southern campaign, in which their complementary strengths would so expeditiously blossom, seems almost determinative for colonial purposes. The astute, meticulous Rhode Islander with gifted strategic skills and the unlettered, frontier Virginian of innate tactical gifts and inspiring leadership—of such random alliances are battles and campaigns won or lost.

Audaciously, Greene divided his small army on December 21, dispatching Morgan with 650 soldiers westward across the Broad River to present a threat to the important British outpost located at Ninety-Six. Upon discovering Greene’s move, Cornwallis ordered a similar force under Tarleton to march westward, countering Morgan’s maneuverings. Greene informed Morgan: “Col. Tarleton is said to be on his way to pay you a visit. I doubt not that he will have a decent reception and a proper dismission.” Almost concurrently, Cornwallis reminded Tarleton by letter that he must ensure the safety of the fort at Ninety-Six and added: “I should wish you to push Morgan to the utmost.”

Morgan loosened his cavalry troop under William Washington to boldly harass Loyalist forces in western South Carolina. However, when Tarleton’s strong relief column approached Ninety-Six, Morgan began to fall back toward the North Carolina state line where he could reasonably expect militia reinforcements. Tarleton obtained the services of the 17th Dragoons and the 7th Fusiliers from Cornwallis, strengthening his column that contained his Loyalist Legion and the 1st Battalion, 71st Highlanders. He immediately began an active pursuit. Across the Enoree and Tyger Rivers marched both the pursued and the pursuers. Bridges were nonexistent in the backcountry and so fords became valuable possessions, especially during the rainy season. Water temperature was just above freezing, and shivering soldiers marched with icicles hanging from their gaiters. As he neared the banks of the Pacolet, Tarleton suddenly swerved westward, crossing at Eastwood Shoals in an attempt to cut off Morgan encamped at Burr’s Mill on Thicketty Creek. The green-coated Legion Dragoons almost caught Morgan in camp but the “Old Waggoner,” as he labeled himself, escaped and rapidly fell back toward the Broad River.

Tarleton was convinced that Morgan had committed to an outright retreat and would continue to flee across the Broad River, so he awakened his soldiers at 3 am and pushed his advance relentlessly despite disorder among his leading units. When Tarleton’s advance guard of Dragoons came out of the tall pines at Cowpens, he was both surprised and pleased to find the colonials calmly awaiting their pursuers. Tarleton, with little respect for the prowess of colonial militia, was certain that Morgan had erred by preparing to give battle with a river at his back. Predictably, Tarleton proceeded to attack at once lest the Americans again retreat.

But Morgan had garnered valuable time by rapid marching and he wisely utilized it to select advantageous ground on which to fight. He then fed his troops and carefully positioned each unit according to his perceived plan. It was as if Tarleton’s hounds, in full bay, had pursued the colonial fox, panting and excitedly chasing him to ground, only to discover that their quarry was confidently arrayed before them, arrogantly preparing to resist.

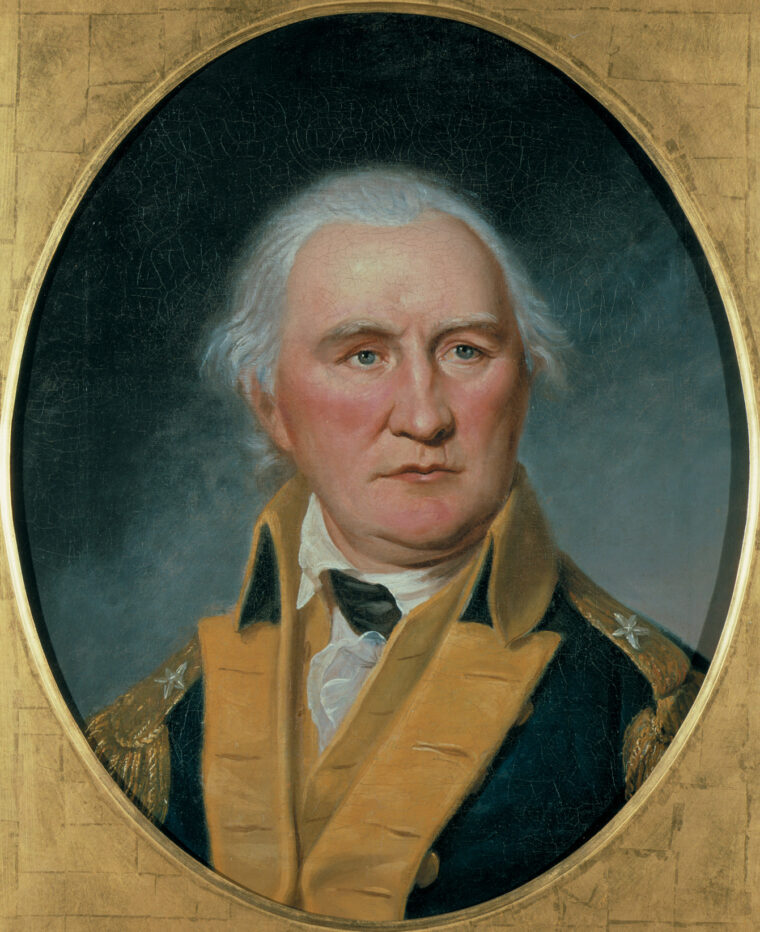

The small colonial army, awaiting battle in the cold mist, was led by a true frontiersman, Daniel Morgan of Winchester, Va. This 45- year-old, unlettered, some would even say uncivilized, product of the Southern backwoods was bent and scarred in appearance, but still perhaps the physically toughest man on the field. Morgan wore no sign of rank except a sword, but in the frontier tradition he was the easily recognized leader. He lacked the sophistication expected of an army commander, but had demonstrated his accomplishments as a militia officer at company, battalion, and regimental levels. Loud, profane, and uncouth, he was also cunning, woods-smart, and blessed with considerable amounts of plain common sense. Underestimated most of his military career by friend and foe, on this day he would demonstrate conclusively his tactical military abilities.

Born in New Jersey around 1735 of Welsh immigrant parents, little is known about Dan Morgan until he appeared in Charles Town, Va., at age 17. About 6’ 2” and 220 pounds, Morgan was a strong, hard worker and quickly amassed funds that enabled him to purchase a wagon and team. He began operation of a freight-hauling business, the colonial equivalent of today’s long-distance, independent trucker. As his business grew so did Morgan’s unsavory reputation as a hot-tempered, barroom brawler, an uncensored womanizer, and a frequent consumer of local apple brandy. Arrested repeatedly for charges such as horse stealing, assault, and resisting arrest, he conducted a continual feud with the Davis brothers and other frequenters of Battletown’s (present Berryville, Va.) infamous taverns. Morgan seemed headed toward long-term incarceration or worse until he suddenly took up with a 16-year-old sprite, Miss Abigail Curry. Remarkably, in short order, Daniel Morgan, never fully tamed, was at least partially domesticated.

When the British Army was formed to march against Fort Duquesne in 1754, Morgan obtained a contract as a wagon driver. When the red-coated column was ambushed and routed by French and Indians, Morgan hauled many of the wounded soldiers back down Braddock’s Road. Somewhat later, Morgan found himself the wagon boss of a British supply column near Fort Lewis on the Roanoke River at Salem, Va. He was unusually overbearing with his drivers in the accustomed frontier style, sometimes kicking or cuffing the laggards. One old wagon driver named Fisher related a story that was retold so often it almost came to characterize Dan Morgan:

One day Fisher saw Morgan kicking several drivers and swore if he played such a prank on him he would taste the butt of Fisher’s rifle.

“Soon Morgan passed down the line and gave Fisher a kick. The offended arose, followed Morgan, and struck him in the head, driving the bully down onto the ground. With that several other waggoneers ran up and laid into Morgan. A young British Ensign ran to see what was the ruckus and as a dazed Morgan bound up to his feet he grabbed the Ensign by the throat … thinking the Ensign had something to do with the drubbing he had received. Within moments a file of red-coats had Morgan.

“He was sentenced to 500 lashes for laying violent hands on an officer of the Crown—300 to be given on the spot until his back was raw as beef—next morning he received the additional 200. Later Morgan joked that the drummer had erred and he only got 499 lashes and that King George owed him another lash. For six weeks, Morgan lay at Fort Lewis, his survival uncertain.”

This harsh punishment, although quite common in British military regiments, would probably have killed many lesser men, and it left Morgan, already a marked individualist, with little toleration for Crown authority. Returning home to Winchester, Morgan became a respected militia leader, excelling in the persistent pursuit of Indian raiders. In the spring of 1756, while carrying military dispatches, a hostile shot Morgan in the back of his head, the ball exiting through his left cheek and taking out several teeth. He escaped his assailants through the exertions of a courageous mare that outdistanced his racing pursuers, but Morgan was left with a permanent facial scar, one that he wore as a badge of honor.

Morgan married Abigail and they settled on a 255-acre purchase near Winchester. When the political differences between colonists and mother country flared into revolution, Morgan anxiously volunteered for service. Assigned initially to command a Virginia rifle company, his unit of 96 long riflemen was dispatched on July 17, 1775, to march the 600 miles to Cambridge, Mass., and reinforce General Washington’s army. Captain Morgan’s reputation skyrocketed when others witnessed the shooting accuracy of his long riflemen. Marching through the snows of Maine to attack Quebec alongside Benedict Arnold, he was captured during the misfired assault with most of his men and imprisoned in the Citadel atop the city.

Well treated by his captors, Morgan fortuitously avoided the smallpox epidemic that swept the ranks of retreating colonials. Later released, he and his reconstructed rifle unit performed a key role in the harassment and surrender of General John Burgoyne’s British Army at Saratoga. Morgan’s frontier leadership skills and courage were openly evident in each of these fights, but his gruff manner and social skills were considered inadequate for a general officer and he was snubbed for promotion to brigadier general. Suffering badly from sciatica initiated on the march to Quebec, he left the army discouraged and returned home to Virginia. Bent and seemingly much older than his years, Morgan was administered icy baths by Abigail, grumbling constantly over the political machinations of the American army.

Then in 1780 Morgan was activated by Congress, promoted to brigadier general, and ordered south to take command of light troops. While he had never before led an independent force of more than a few companies of riflemen, he was a natural leader, an innately tough, merciless captain, respected and feared by the backwoodsmen. When he aligned his troops at Cowpens, Daniel Morgan still had no creditable military reputation but, most importantly, was supremely confident in his own ability to lead a “fight.” And this he brilliantly accomplished.

Morgan’s little force was a hybrid army of Continental line soldiers, state regimentals, and militia, accompanied by Continental Dragoons and volunteer cavalry. His five companies of Continental line troops—three from Maryland, one from Delaware, and one from Virginia—were experienced, steady soldiers led by the very capable Lt. Col. John Edgar Howard. These blue-coated Regulars enlisted and were paid by the Continental Congress, though still retaining their state regimental numbers and names. Morgan’s state troops were primarily from Virginia and these were exceptional in that each contained a number of recently discharged ex-Continental Regulars. Moreover, most of these men were from the western or backcountry counties of Augusta and Rockbridge and were armed with deadly long rifles.

Morgan’s militia units from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia embraced a wide range of experience and expected military value. They were armed with every possible weapon from rifles to shotguns. When Colonel Thomas Sumter refused to report, offended somehow by Greene and upset with his role in the campaign, the affable General Andrew Pickens took command of these assorted militia units, perhaps a fortunate circumstance for Morgan. The rotund Lt. Col. William Washington, a kind, lax disciplinarian who turned into an energetic, merciless fighter when the bugles blew, commanded the 82 American Dragoons to which about a hundred attached militia riders possessing swords were added.

Morgan’s exact numbers are hard to ascertain. He marched from Charlotte with about 650 men and was reinforced by militia units right up until the night before the battle. Most sources credit Morgan with 1,000 to 1,100 men, but historians who have reviewed the pension records feel a reasonable estimate would be 1,300 to 1,400 soldiers. Morgan’s men enjoyed soaring morale. Historians George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin report in their Rebels and Redcoats that a 17-year-old militiaman named Thomas Young recalled, “We were very anxious for battle … and Morgan went about among the volunteers all night, visiting their fires and joking of the mornings [sic] fight.”

Morgan’s antagonist, the somewhat arrogant yet genteel Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, was an ideal antithesis to the backwoods frontiersman. He was smooth, glib, well educated, and a marvelous horseman. Born in 1754 near Liverpool, England, the third son of the mayor of Liverpool, young Tarleton was reared in comfortable circumstances, attended Oxford University, and enrolled in the Middle Temple, England’s finest law school. When Tarleton’s father suddenly died, leaving him some inheritance, he dropped out of school determined to live the life of a rake and gambler. Soon his financial resources disappeared and he began searching for a career. His family assisted by purchasing a coronet’s rank in the 1st Regiment, Dragoon Guards for 800 pounds and Tarleton was instantly transformed into an innately capable cavalry soldier. He volunteered for service in the colonies where opportunity for promotion seemed ripe.

Short in stature, Tarleton was well proportioned and very strong and muscular, cutting a magnificent figure on horseback. Red-haired and dark-eyed, with charm and sophistication, he appealed to all women regardless of age, social station, or political persuasion. On one occasion, discovered with the mistress of a fellow British officer, Major Richard Crewe, Tarleton barely escaped a duel that would probably have terminated his military career. His amorous successes with American lasses also contributed significantly to the detested status he rapidly attained among the colonists. Initially he drew service in the New York area and soon became known for dashing raids, sudden attacks, and all-night rides requiring tremendous physical exertion. Although inclined toward impulsiveness, his drive, ambition, and persistence, coupled with talents in intelligence-gathering, made Tarleton an ideal cavalry officer.

Tarleton was promoted rapidly to lieutenant colonel when not quite 24 years old. He was appointed to command the “British” Legion, a unit composed of Loyalists from Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey. The Legion, half cavalry and half infantry, wore green jackets faced in black with huge black helmets and green plumes. Tarleton advocated the primary tactical use of cavalry in headlong charges or in flanking the enemy, causing him to scatter, then to relentlessly and mercilessly pursue and punish the foe. He developed a successful pattern of operation: a swift march, a surprise appearance, and an immediate attack utilizing swords and bayonets. These tactics stood him in good stead against ill-disciplined colonials

Tarleton’s genius as a Dragoon blossomed when he and his legion accompanied Clinton on the second investment of Charles Town. After landing in Edisto Bay, Tarleton found himself without horses—most died on the hard voyage south. He promptly confiscated mounts of every description from nearby farms and plantations and proceeded to cut American supply lines into the city. At Monck’s Corner he defeated the American cavalry and Charles Town’s fate was sealed. Dispatched north to capture a regiment of retreating Continentals, he pursued and attacked the 10th Virginia Regiment in a slashing head-on attack at Waxhaws near the state line. An absolute rout ensued and Tarleton was accused of allowing his Dragoons to shoot down wounded and surrendered Americans.

He denied these charges claiming he was pinned under his horse, but the ratio of killed and wounded was so inordinately high as to belie his defense. His reputation among his adversaries became extremely negative, and Americans who proposed to offer him no quarter offered a price for his head and coined the term “Tarleton’s Quarter.” While he may have permitted excesses on occasion, and he surely burned the property of patriots and hung several turncoats, Tarleton was probably no better or worse than other cavalrymen of both armies. The bitter, punitive nature of warfare in the South, often among neighbors and individuals who changed sides repeatedly, exasperated the efforts of the best commanders. Strangely, Tarleton seemed to pride himself in the hostile titles and threats offered by his foes. He reasoned that the fear and demoralization among his enemies caused by his reputation more than offset any real danger to his person.

Tarleton enjoyed his stay in the Charles Town area, daily appearing at the city’s famed bordellos and taverns. Of all the colonial cities occupied by the British Army, the South Carolina seaport was favored because of its balmy climate, cuisine, and beautiful ladies. Tarleton followed this initial success with a victory over General Thomas Sumter at Fishing Creek when he surprised his foe with a rapid, hot chase. Months later Tarleton was repulsed by the same Sumter when forced to engage in a stand-up fight at Blackstock’s Farm. Tarleton’s cavalry skills as a drive-and-slash leader were apparent. But he still seemed somewhat out of his realm when faced with a set-piece fight.

Now Daniel Morgan had skillfully feigned panic in his retreat, drawing Tarleton forward in a helter-skelter fashion. Then the old frontiersman calmly prepared a trap and presented Tarleton with a set battle.

Tarleton’s army was actually a mixed bag of soldiers. Alongside his British Legion of American volunteers, Cornwallis provided him with portions of several light infantry units unified to form a light infantry battalion of 110 men. Additionally, four companies of the 7th Regiment of Foot or Fusiliers, totaling 167 soldiers, were included. These recent Irish recruits, whose red coats were faced with blue, had no previous combat experience so were designated to serve as garrison troops. His strength was in the line companies of the 1st Battalion, 71st Highlanders, red coats with white facing, gaiters, and trousers replacing their summer wear of kilts, and marching to their pipes and drums. These 250 soldiers under command of Major Archibald McArthur were considered superlative soldiers in the tradition of the Empire. Tarleton’s mounted troops were the 17th Light Dragoons and the British Legion Dragoons. The 17th retained its red coats while his largest contingent, the British Legion Dragoons, were attired in their distinctive short green jackets with black facings and huge dragoon helmets. Two artillery pieces, three-pound grasshoppers, accompanied the column with an appropriate contingent of artillerymen.

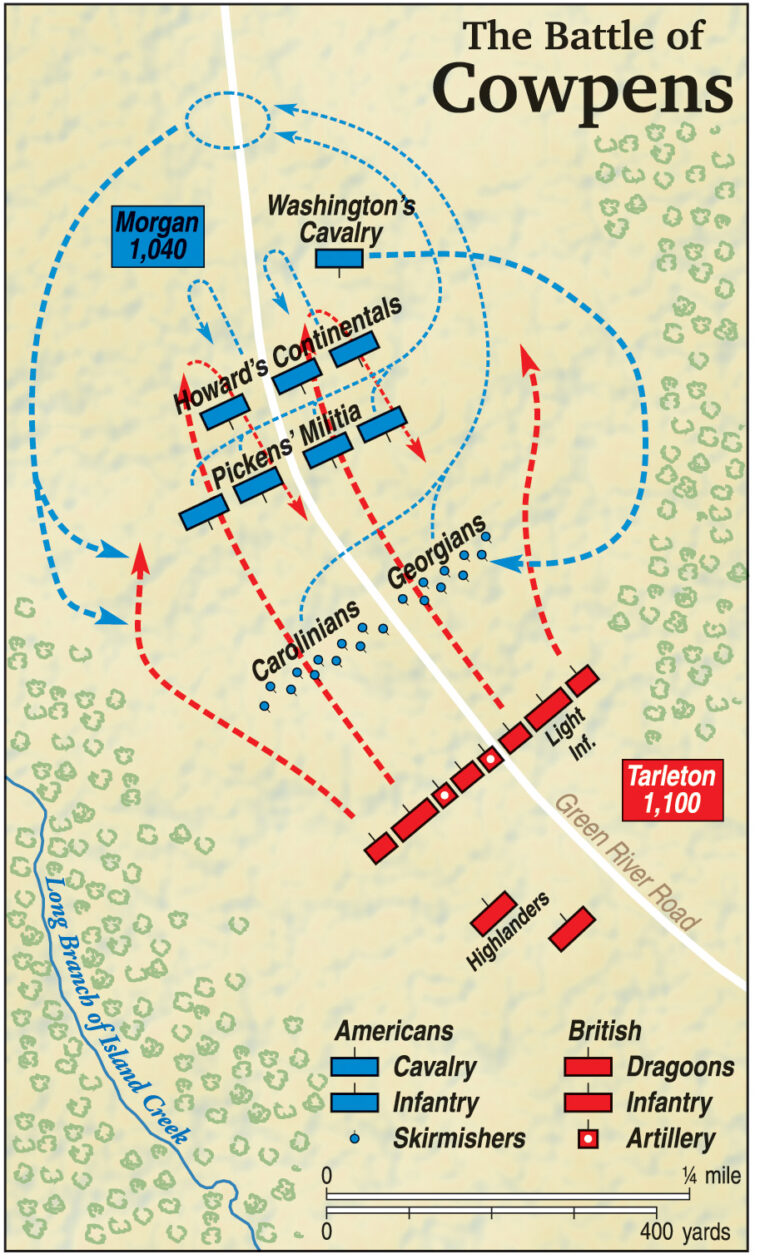

According to Edwin Bearss in his Battle of Cowpens, Morgan’s initial dispositions at Cowpens were almost brilliant, certainly highly unorthodox. He placed his soldiers in three distinct lines of defense, each partially screening its successor. This defense in depth was designed to wear down the British attackers as they were forced to advance against progressively stronger lines of defenders. The Americans were positioned on slightly sloping ground in an open, grassy field surrounded by woodlands of hickory, oak, and chestnut trees with minimal underbrush. Good defensive ground in that, much like Gettysburg, Pa., the strengths were not so readily apparent and did not appear so stout that an enemy was unlikely to attack. Morgan met with his captains on the evening before the fight, carefully explaining the role and expectations of each unit, even drawing a map. But the old frontiersman asked for no advice or counsel—he would make his own decisions. He later claimed that he knew his adversary and was confident of a head-on, straightforward attack. Morgan awoke his soldiers early next morning for a hot breakfast and merrily assured the anxious militia that “Benny was coming,” but also that if each man did his duty they would send Ben running.

The initial American line was actually a strong skirmish line of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia militia under command of Majors Joseph McDowell and Charles Cunningham. In widely scattered groups about 150 yards in advance of the second and main militia line, these riflemen calmly awaited the enemy. A third line at the crest of the slope was composed of the five 60-man Continental line companies flanked on either side by several units of experienced Virginia state troops. Tarleton was therefore forced to assault three lines, each progressively stronger than its predecessor. Morgan’s cavalrymen, Continental Dragoons, and mounted militia swordsmen were grouped behind the third line under Colonel William Washington.

The impulsive Tarleton, always willing to fight, never hesitated. Ordering his leading elements to drop their packs and deploy, he decided to attack at once. Initially he ordered his Legion Dragoons to scatter the skirmish line, but when that effort failed owing to wet ground and lackadaisical effort, the infantry deployed. The light infantry battalion and British Legion Infantry were aligned in two-deep ranks to the right of the Green River Road or Mill Gap Road, which split the field, and the 7th Fusiliers aligned similarly left of that landmark. A three-pound gun was unlimbered on the road between the attack units and a second aligned in an interval amid the 7th. The 17th Dragoons were deployed on his right flank and a unit of British Legion Dragoons on the left. When the 71st Regiment, Fraser’s Highlanders, arrived, they formed in reserve.

As soon as the British line stepped off to the beat of their drums, the American skirmishers began to fire. Thomas Young, the militiaman who was also celebrating his 17th birthday on this day of battle, called the advance “the best line he ever saw … they gave a loud British halloo and came at the trot.” But the American rifles were deadly and the marked officers and artillerymen began to fall. On came the British line absorbing the rifle fire until, presenting bayonets preparatory to charging home, the American line faded away, the skirmishers moving rapidly backward and sifting through the gaps of the militia line to the rear. Tarleton, riding up front—for he was certainly no shirker—clearly observed the second American line and decided to press on without reforming, speed being essential to breaking the American position.

Morgan’s second line comprised four battalions of South Carolina militia. Well-recognized local officers led these battalions: Lt. Col. Benjamin Roebuck, Colonel John Thomas, Lt. Col. Joseph Hayes, and Colonel Thomas Brandon. Responsibility for the entire line was exercised by the dour-faced but rock-steady Colonel Andrew Pickens. The skirmishers, North Carolinians under McDowell and South Carolinians led by Cunningham, after falling back, infiltrated the militia line, reforming on the flanks or in the gaps. Tarleton’s infantry, at full cry, continued forward, discharged their two cannon and repeated their short, staccato cheers. Small rifle parties fired at the officers but upon the urging of Morgan and Pickens the militia line held its fire until the British line was 30 to 40 paces distant. They then unleashed an aimed rolling volley that seriously injured the attacking line.

The British troops were staggered. Some hesitated for a time, in particular the 7th Fusiliers, who required their officers to apply the flats of their swords to move them forward again. But the Redcoats came on with bayonets shining, intimidating the colonial militia. Some American units were caught with unloaded guns. The militia line broke first in the center and then folded and dissolved. These temporary soldiers fled to the safety of their third line, some in obvious panic. The 17th Dragoons on the British right under the ebullient Irishman, Lieutenant Henry Nettles, charged the fleeing militia of the American left with great effect, riding among the fugitives and utilizing their sabers on the heads of the fleeing colonials. They were countered abruptly, however, by a stern charge of William Washington’s colonial cavalry. James Collins, a militiaman running for his life, recalled that “we fell back to our horses and then the British cavalry overtook us and started to hack. Suddenly like a whirlwind Col. Washington’s horsemen hit their disordered flank and drove them out of sight.” Outnumbered by the British horsemen, the colonials enjoyed the advantage of superior horseflesh. They rode mounts of thoroughbred-draught-stock mix, strong horses far superior to the confiscated pleasure mounts of the British.

British casualties were unusually heavy at the militia line and the survivors cheered at the retreat of their opponents while momentarily halting to reform and reorganize their front. Now, staring at a third American line, they tightly dressed their lines and awaited orders, the three assault battalions compressing to conceal their losses. Soon the British front again began to advance to the drumbeats, despite continued rifle fire. Halting at close range the advancers traded volleys with the blue-clad American Continentals. Mounted officers such as Morgan and Tarleton ranged the front, miraculously uninjured. The firefight increased in intensity and for almost 15 minutes seemed about even in results. Spotting backwoods militia by their distinctive hunting jackets, Tarleton targeted these units, which were aligned on the American right. He summoned his reserves, the best fighters in his army, the Highlanders of the 71st, to advance on the double, bonnets of black and green plaid appearing from the smoke, accompanied by the Legion Dragoons, to turn the American right flank, an occurrence he expected to precipitate an American rout. McDowell’s riflemen, concealed among the trees, disputed this movement with rifle fire until Major McArthur’s Highlanders, their shrill pipes keening, broke into a run, shattering their ranks. Again Washington’s cavalrymen thundered to the rescue, checking the Legion Dragoons.

Colonel Howard, recognizing the pressure of the Highland advance on his flank, attempted to refuse his right by folding back like a swinging gate his far-right elements, the Virginia State Troops under Captain Edmund Tate. However, misunderstanding the order, or ignorant of how to obey the command, the Virginians marched directly to the rear rather than folding to their left. This movement uncovered the adjoining units that were then forced to follow in succession as they recognized their flank was exposed. This linear withdrawal occurred in a succeeding fashion and not simultaneously, thus producing the effect of an “en echelon” retrograde movement. Morgan, observing this mistake, intuitively reacted. Spurring his horse to the top of a slight rise, he drew a line in the dirt with his drawn sword, marking a point at which he instructed his officers to halt and redress their units.

The British infantry, already exhausted from their strenuous efforts, lost all order when they suddenly observed the backs of the Americans and sprinted wildly forward in pursuit of what they perceived as a routed foe. Their few surviving officers vainly protested the undisciplined dash because they noted the American infantrymen were marching rearward still under the control of their officers. The colonials were carrying their weapons at trail arms, loading as they moved.

Upon reaching Morgan’s designated point, the American units halted, dressed their line, turned to their front in a slightly oblique fashion, cocked their weapons, and fired by volleys, right to left. The sprinting enemy pursuers were devastated as they were caught breathless and largely with unloaded weapons. The British line was crippled. At this critical moment, Howard ordered a bayonet charge by his American Continentals. Moreover, William Washington’s cavalry, having defeated the Legion Dragoons, exploded into the Highlanders’ left flank as McDowell’s previously scattered sharpshooters reappeared and closed on the British flanks. Only the Scots and the artillerymen fought on, the gunners to the last man. When the 7th Fusiliers surrendered, Howard could then wheel his entire contingent on the Highlanders.

The survivors of the proud 71st were surrounded. John Howard recalled that “they laid down their arms and their officers delivered up their swords.” Morgan permitted absolutely no abuse of his captives, to the surprise of the British officers, who openly expressed their fear that no quarter would be granted. Vainly, Tarleton attempted to lead his British Legion to rescue the Scots but this unit deferred. Washington spurred his colonial horsemen in pursuit and initiated a lively duel with Tarleton and a number of supporters. The two antagonists exchanged sword thrusts, with Tarleton sustaining a serious wound to his right hand. Washington, whose sword shattered, was perhaps saved by the timely intrusion of his 14-year-old bugler.

At this point, the fight was finished. British losses were more than 120 dead, several hundred wounded, and almost 900 captured. An embarrassed McArthur remarked to Colonel Howard, “Nothing better could have been expected when troops were commanded by a rash, foolish boy.” McArthur’s comments, coming immediately after his capture, probably reflect his ill humor at his circumstance, but they cannot be lightly dismissed.

The impulsive, hell-for-leather Tarleton, personally brave and always aggressive, did not exhibit nor possibly possess the patience and tactical expertise required to oppose the American alignment. When he faced Morgan’s unusual battle lines, the young cavalry leader reacted by launching a direct head-on assault without proper reconnaissance. He neither utilized his artillery advantage nor awaited the arrival from the rear of his best troops, the feared Highlanders of the 71st.

Morgan’s adroit use of a combined force of long-rifle-equipped militiamen and bayonet-wielding, musket-armed Continentals espoused the strengths of each and countered Tarleton’s frontal assault by gradual erosion of his strength. The American commander’s innovations in utilizing tactics that combined these diverse units were amazing, for he had no false illusions concerning the militiamen. He was one of them and appreciated their fighting abilities but also understood their weaknesses in facing the cold steel of British Regulars. He found a method to achieve maximum results from their efforts, while concealing their liabilities. For the first time an American army had tactically confronted and defeated a British army of comparable strength on the battlefield. The crude backwoods saloon fighter had matched wits and bested a suave, intelligent, British-trained officer and achieved a significant victory for his country.

The triumphant backwoodsman consolidated his spoils and, paroling the officers, rapidly started his army and captives north across the Broad River. Many of the captive Scots would ultimately reach prison camps in Winchester. Augusta and Rockbridge County militia, whose enlistments had expired, started over the mountains to the Valley of Virginia escorting more than 500 captives. As Morgan expected, a disappointed Charles Cornwallis was soon in pursuit, anxious to punish Morgan and rescue his Scots before Morgan could unite with Greene. But Cornwallis marched toward Cowpens expecting Morgan to tarry there rather than move north so quickly. Crippled by recurring sciatica when he reached the Catawba River, Morgan reluctantly informed Greene that he must leave the field. Unable to stand or ride, he could travel only in a “chair” (a one-horse light chaise).

Years later, the soundly beaten Tarleton admitted that his defeat, coupled with the demise of Ferguson’s force at Kings Mountain, was a catastrophe to British aims in the American South. He was unusually complimentary in his praise of the good conduct and bravery of his colonial opponents, but he would never admit that Morgan had outgeneraled him despite being so advised by one of his subordinates, Lieutenant Roderick MacKenzie. Cornwallis declined to reprimand or censure Tarleton but he commented later that “this affair has almost broken my heart.”

The limited size of the two armies that clashed at Cowpens has tempted historians to minimize the significance of the action. In such a transient, fluid arena of conflict militia units—both Loyalist and patriot—formed, fought, dissolved, and reassembled. This sound defeat of Tarleton, who had conducted such an unrelenting, merciless harassment of patriots and their sympathizers, constituted a major morale coup. Each British defeat eroded the Loyalist base in the Carolinas and increased the influence and recruitment of American partisans. But perhaps equally important was its negative effect on the morale of British soldiers. Isolated in a wild country such as the Southern backwoods, involved in what has been termed a partisan war, a religious war, or even an uncivil war, the British rank and file maintained unshaken confidence in their ability to rout American militia in any clash of arms. The defeat at Kings Mountain could be explained as an ambush by long-riflemen, and by the fact that the British troops were Loyalists not Regulars. But here at Cowpens, American Continentals and militia beat a British Regular field force for the first time, and so completely defeated them that there could be no denial.

Despite desperate attempts by the British to cancel the setback, Cowpens was the linchpin of American success that led directly to Yorktown and eventual independence for the American colonies. Noted British historian Charles Stedman accorded that “Cowpens formed a very principal link in the chain of circumstances which led to the independence of America.”

I’m extremely grateful for the rude, undereducated, country raised & fed pre-American colonials. Who made AMERICA GREAT! Seems that trait still exists🤔