By Herb Kugel

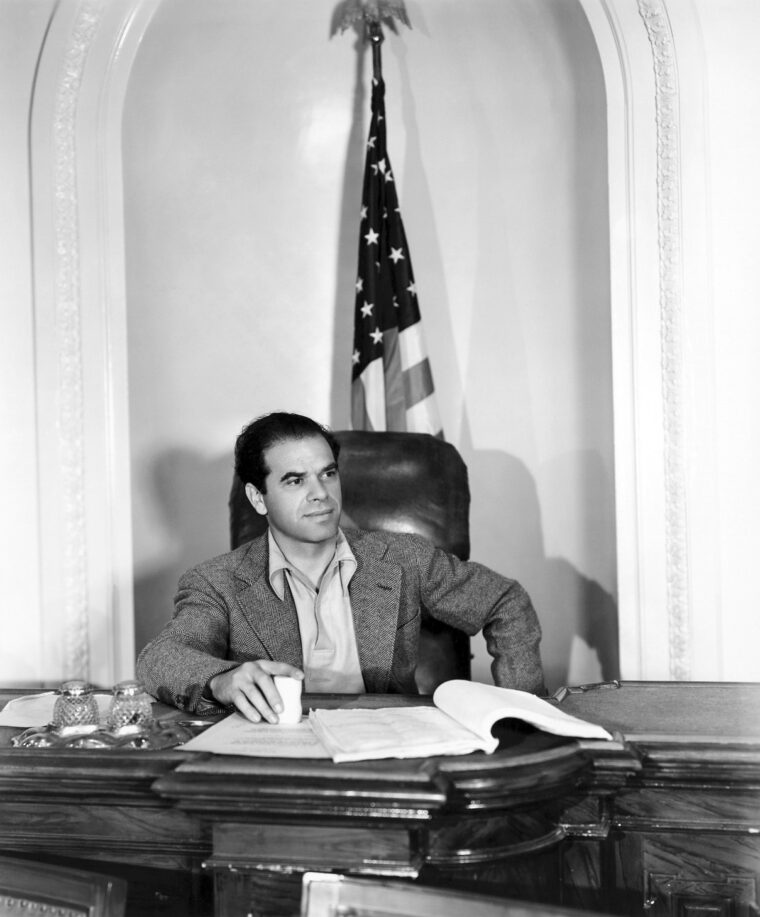

In his 1971 autobiography, The Name Above the Title, prestigious Hollywood film director Frank Capra claimed that on Monday morning, December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, two U.S. Army Signal Corps officers came to the Warner Brothers Studios soundstage where he was editing his film Arsenic and Old Lace.

He said that the officers then swore him into the Signal Corps and that he asked for and received an extension to finish his film. Then he received, on February 5, 1942, a telegram directing him to proceed to Washington, D.C., six days later.

Unfortunately, little of this appears to be true. Two officers did go to Hollywood on December 9, but they did not come to swear Frank Capra into the Army. The officers, Colonel Richard I. Schlosberg and Captain Sy Bartlett, were in Hollywood for a one-day series of discussions on the expansion of the wartime film training program. The two men met with Colonel Darryl. F. Zanuck, supervisor of Army Signal Corps training films.

Zanuck, the head of 20th Century-Fox, like all the other Hollywood studio moguls, was commissioned a colonel in the Army Signal Corps. Swearing Capra into the Army on December 8, 1941, was not on the agenda.

What came up later relating to Capra began with a telephone call made on December 9, by Brig. Gen. Frederick H. Osborne, chief of the Morale Branch of the War Department (later called the Information and Education Division of Special Services). Osborne had been contacted by Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall regarding a series of films Marshall urgently wanted made to teach American soldiers just why they were fighting.

The evidence about what happened next regarding Capra’s enlistment is complex, but the bottom line was that Capra agreed, on December 12, to accept a major’s commission and join the Army Signal Corps. Capra would then make the films Marshall urgently wanted: the now famous Why We Fight series.

Capra was ordered to active duty on January 15, 1942, but was given an extension to complete Arsenic and Old Lace. Capra was actually sworn into the Army on January 29, 1942. He did not take his oath on a film studio soundstage as he claimed in his autobiography but was sworn in at the Southern California Military District Headquarters in Los Angeles. With the exception of receiving an extension to allow him to complete Arsenic and Old Lace, the rest of Capra’s account of his enlistment is apparently totally untrue.

The question arises as to why a brilliant motion picture director, the winner of six nominations and three Academy Awards for best direction for It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and You Can’t Take it With You (1938), as well as the Directors Guild of America’s D.W. Griffith Award in 1958, and three honorary doctorates, would write such an autobiographical fantasy? Why was the man who was personally awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by General Marshall on the day of his military discharge on June 15, 1945, creating a fantasy about his enlistment some 15 years after the event?

It is not known why Capra wrote this egocentric story, but it was thought to be due to emotional problems dating back to his grim early childhood. Because of untrue sections in The Name Above the Title, some critics have wrongly attacked the entire autobiography. With watchful reading, there is much that can be learned about Capra and the genuinely important work he did that is not available from other sources.

Francesco Rosario Capra was born in Bisacquino, Palermo, Sicily, on May 18, 1897. He suffered a painful birth––born frail, badly dehydrated, and not expected to live. The story handed down by Capra’s family was that little Francesco was left to die while friends and relatives spent their energies caring for his mother, doing this until her father, Capra’s grandfather, came to Francesco’s rescue. It is presumed that his timely intervention saved Francesco’s life.

Capra suffered through a bleak childhood. He spent his first six years with his family on a Sicilian farm. In May 1903, Capra’s father scraped up enough money for the family to immigrate to America. The family sailed from Palermo to Naples. Then, on May 10, 1903, their ship set sail for the United States. Francesco and his family suffered through a nightmarish steerage crossing before landing in New York harbor on May 23.

Capra later said of his Atlantic crossing: “There’s no ventilation, and it stinks like hell. They’re [the family] all miserable. It’s the most degrading place you could ever be.”

The family then endured a ghastly railroad trip across the United States to the Southern Pacific Railroad Station in downtown Los Angeles. Capra recalled: “For the kids, the train was the worst. The seats were wooden, and that’s where you were seated day and night. They locked the cars so you couldn’t move around, and you slept there….”

They arrived in Los Angeles on June 3, 1903. Frank saw his father bend down and kiss the ground when the family left the train.

Capra, according to some, personified the rags to riches American dream. It allegedly began when he sold newspapers on Los Angeles streets at the age of 12 and then extended to his enjoyment of extreme wealth when he became a renowned film director.

However, rags to riches ignored a dark side in Capra’s psyche. One Capra associate said, “Capra was always coming to America.” Given his difficult ship and train trips to and across America, this was not a good thing to have been seen about him. Another associate said,“Capra was driven by self-doubt as much as his belief in the power of the ‘little man.’”

One thing was certain, however. Capra, the sickly child and unhappy little immigrant boy who initially hated America because of his childhood misery, the man who changed parts of the story of his life in his autobiography to make himself appear more important than he really might feel, grew to love his adopted country deeply and would do everything he could to help the United States win World War II. Whatever Capra’s personal demons, the work that he would be doing for the Army held his demons at bay and allowed him freedom to fight ogres of a different kind––the ones that had been unleashed by Germany and Japan.

In May 1941, the Nazis’ 114-minute propaganda film Sieg im Westen (Victory in the West) played to enthusiastic audiences in Manhattan’s Yorkville District of New York City, then an area with a large ethnic German population.

Sieg im Westen, produced by the German Army High Command, merged two themes, the first a prologue that narrated a Nazi version of European history and the origins of World War II, and the second that graphically illustrated the power of the Nazi blitzkrieg in Western Europe in the spring of 1940.

The movie was spliced together with sections from Leni Riefenstahl’s 1934 epic German propaganda documentary Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will) and current German military newsreel footage. The film’s purpose was to illustrate the aggressive boldness of the German blitzkrieg and the superiority of German arms. The film also claimed that German military power was needed because Germany was not permitted to live in peace.

Arch Mercey, the assistant to Lowell Mellett, the director of the U.S. Office of Government Reports, wrote to his boss after viewing the film: “The applause…is amazing. Hitler naturally enough draws the most applause, but there is plenty for the parachutists, dive bomber pilots, and advance guards.”

The Nazis also produced a second propaganda documentary, the 69-minute Feldzug in Polen (Campaign in Poland), a film that depicted the 1939 German invasion of Poland and the ethnic Germans living in Poland as a downtrodden minority. There was much more in the way of propaganda, and the film was regularly given to and screened by German overseas minorities to express the German point of view.

The U.S. government had absolutely nothing to compare with films such as these either in quality or quantity. In 1941, it produced a total of 25 films on national defense, but the American film industry, extremely reluctant to give away any theater time, refused to show any government film that was more than three minutes in length.

In addition, the film industry’s certainly misnamed Motion Picture Committee Cooperating for National Defense demanded to see the outline and script of each government film before passing judgment on whether it would allow the film to be shown in theaters. Mercey wrote Mellett: “The Committee is exercising a censorial power over the government at the moment.”

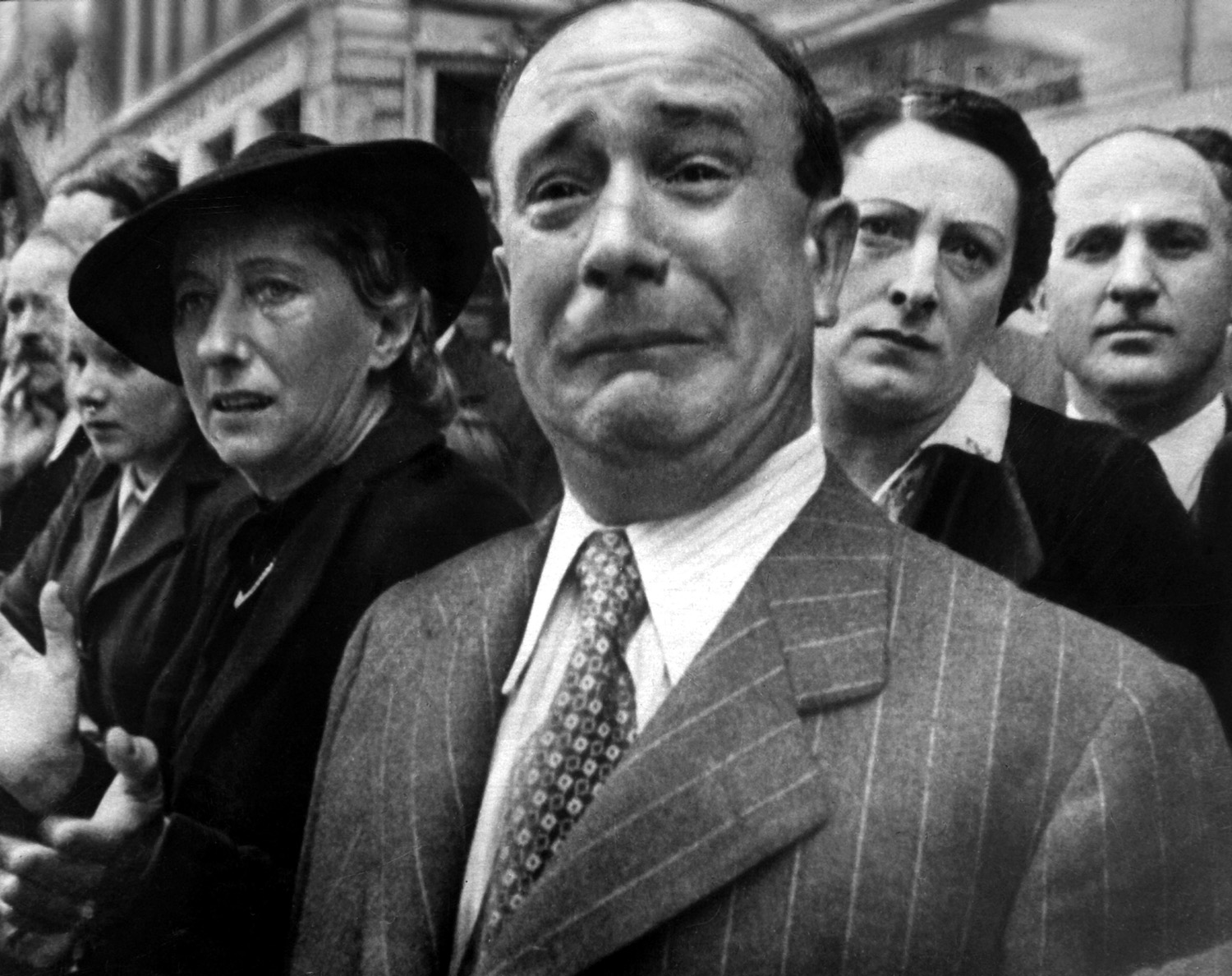

The American government had been certain for some time that war was coming––and soon. When the Selective Training and Service Act, the first peacetime military conscription act in American history, was implemented on September 16, 1940, it triggered a growing apprehension about the motivation and morale of the new conscripts. Renowned Kansas newspaper editor William Allen White wrote Lowell Mellett that the new conscripts “haven’t the slightest enthusiasm for this war or this cause. They are not grouchy, they are not mutinous; they just don’t give a tinker’s dam.”

The government’s concern spread to the highest military levels. General Marshall read a May 1941 Atlantic Monthly article by Stewart Alsop, “Wanted: A Faith to Fight For.” Alsop expressed deep concern that while the German soldier had a powerful cause for which to fight and die, the American soldier did not.

A worried Marshall was quoted saying, “We’ve got to tell our young men why they’re in uniform. They’re going to fight seasoned soldiers who’ve got a thing going for them, a superman thing, and their soldiers believe it. And we haven’t got that.”

This was why Frank Capra became involved. The Army Morale Branch established earlier to provide military indoctrination failed miserably. General Marshall blamed the “the deadly effects of prepared lectures, indifferently read to troops.… Troops found these lectures to be baffling, bewildering, or just plain boring.”

Frank Capra left for active duty with the Signal Corps on February 11, 1942, and arrived in Washington three days letter. He came into a city heavy with depression regarding the American chances for winning World War II.

Capra was loud in his scorn of defeatism; he quickly went to work producing ideas for scripts and immediately ran into tenacious resistance from the Signal Corps’ bureaucracy. There were obviously many senior Signal Corps officers who wanted to keep the status quo.

Capra believed these officers wanted to shove him aside. He became convinced when he was abruptly transferred from the Signal Corps into the Morale Branch of the War Department. He was now commanded by Maj. Gen. Frederick H. Osborne, under whom he would report directly to Colonel Edward Lyman Munson, Jr., the head of the Information Services Branch, a unit consisting of departments for news, radio, pamphlets, and film.

Capra protested the transfer; he claimed he was a victim of office politics and jealousy. He insisted he was a moviemaker who knew little of morale, but nobody listened to his protests.

“You are the head of the film section, Major,” Munson said, when he met Capra. He smiled. “In fact, you are the whole film section.”

Capra recalled his reply: “Colonel Munson, as a fool who turned his back on Camelot, I don’t feel like jumping up and down over heading a one-man film section.”

Capra recalled the twinkle in Munson’s eye when Munson replied:

“Well, welcome to fantasy land. Here, have some coffee and meet the other Mad Hatters.”

It wasn’t fantasy land. Capra later learned from Munson that his transfer was not office politics but was ordered from the highest levels. He learned that General Marshall did not feel the Signal Corps could make the type of film he strongly felt the Army needed. On the contrary, he was well aware the Signal Corps officers would fight to keep everything as it was.

It was against this background that Capra was ordered to report to Marshall because the general wanted to speak to him privately. Capra, a Catholic, later commented wryly, “Not being a military man, I didn’t … realize that this was tantamount to a private audience with the Pope.”

Munson escorted Capra through apparently miles of Pentagon corridors to a door labeled “Chief of Staff.” Munson explained the rules to a suddenly nervous Capra. Capra was to give his name to the guard inside when he went in, and then, when the guard gave him permission to enter, Capra was to walk directly into the inner office without knocking. Munson stressed that Capra was not to salute. If Marshall was busy, Capra was to walk to the chair at the side of Marshall’s desk and quietly sit down. He was to do nothing else. Capra, now very nervous and alone, did as Munson ordered.

Even though he had been nervous, the film director in Capra later observed that General Marshall “could be cast [in a film] as a sad-eyed Okie watching his soil blow away.” Capra’s legs were trembling, but they were moving as he walked into Marshall’s private office. He later recalled what one sergeant said: “Morale is what makes your feet do what your head knows just ain’t possible.”

Capra and Marshall were alone together for a considerable time, and there is absolutely no reason to doubt Capra’s autobiographical report of their conversation. Marshall spoke frankly. He told Capra that America would raise a large army, about eight million men, and the Army had to make soldiers out of boys, who for the most part had never held a gun.

These boys were to be uprooted from civilian life, sent first to Army camps for training and then shipped to various war zones, and finally into combat. The reasons why they were fighting were often vague or blurred in their minds. Capra later recalled Marshall saying that in a short time America would have a huge citizens’ army in which civilians would outnumber professional soldiers some 50 to one.

Would these draftees survive the rigors they would be put through? Marshall’s answer was “yes,” but only if these boys knew the reasons why they were fighting. Marshall laid down the bottom line when he told Capra, “And that, Capra, is our job––and your job.”

After the meeting, Capra walked into a lavatory, entered a stall, and closed and locked the door. He recalled wanting to be completely alone, to think things through. He knew he didn’t have the foggiest idea how to make a wartime documentary. He had no organization, a very small budget, nothing except a direct order from Marshall and, shortly after that, a newly painted sign on his door reading, “Major Frank Capra, Orientation Film Section.” As Capra later reported, “I was that section.”

As the weeks went by, Capra successfully struggled to fight office politics and build his organization but fought unsuccessfully to find a “hook” on which to tie everything together for his Why We Fight films. He and the men who were joining his now-expanding unit spent hours in the New York City Metropolitan Museum of Art, studying captured or confiscated Nazi films.

In April 1942, Capra suddenly found his answer. Coming directly from a showing of Triumph of the Will, it had been staring him in the face all the time. This was the film that Hitler claimed was “a totally unique and incomparable glorification of the power and beauty of our movement.”

Riefenstahl’s film begins when Hitler’s solitary plane is seen flying, almost magically, through a beautiful German sky and then descending through the clouds to land in Nuremberg. Hitler had come to a Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg, a huge event put together to honor the Nazi movement to generate praise for the party’s leader, the Nazi Aryan superman, Adolf Hitler.

At first Capra, sitting in the darkened theater, was stunned. He was staring at a film that “fired no gun, dropped no bombs. But as a psychological weapon aimed at destroying the will to resist, it was just as lethal.”

“My God,” Capra told one of his new workers, “I can’t compete with that.”

He was wrong. Some time later, Edgar (Pete) Peterson II, a young filmmaker who worked under Capra at Warner Brothers on Meet John Doe, joined Capra’s unit.

“Let their own films kill them,” Capra told Peterson. He wasn’t joking.

His idea was to take the Nazis’ own films and revise, replace, or delete scenes as needed. Importantly, he would rewrite the narration and replace the Nazi soundtrack with his own. He would shoot a few new scenes as needed and add animation for effect. He would change the poisonous snake into a reptile that bites its own tail. While Capra’s solution was miraculous in its simplicity, its implementation would not be easy. Hundreds of miles of film would have to be viewed, reprocessed, and reedited. It would require thousands of hours of work.

Capra began his work with a vengeance. His script went for the Axis jugular and spared no irony, rested on no subtleties. He asked actor Walter Huston to do the new narration; Huston’s powerful voice had been used in many of Capra’s Hollywood movies. His narration is filled with nationalist and racist rhetoric which smears pitiless German “Huns” and “blood-crazed Japs.”

The narration also praised the courage and sacrifice of the British, Soviets, and Chinese. Realistic sound effects and a powerful musical score intensified and embellished the dramatic Why We Fight scenes.

The first Why We Fight film, Prelude to War, for instance, had six of Hollywood’s finest film music composers working on the soundtrack. Capra was not apologetic about its powerful script. America was at war; in 1942, it was not certain if she would win.

The Walt Disney Studios were contracted to produce the animated portions of the films. The Disney organization did much to animate certain concepts to make the film powerful and exciting––not to mention clearly understandable to an audience of GIs whose intelligence varied considerably. For example, weak amoeba-like Polish units were shown encircled then devoured by superior predatory Nazi bacteria. The films were made even more pertinent by Disney’s animated maps, which depicted all Axis and Axis-occupied territories in funereal black and dark grays.

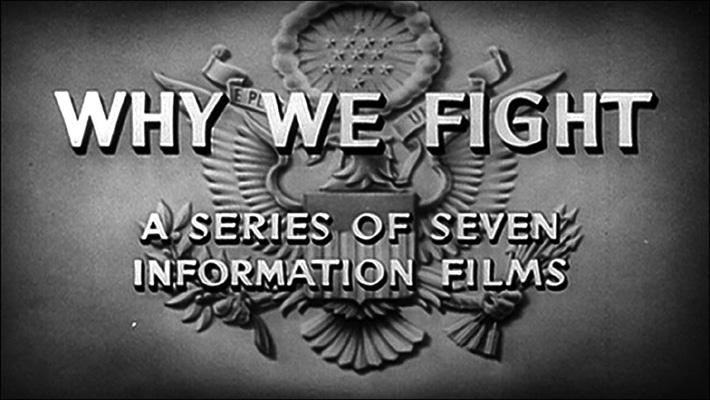

In three years until the end of the war, the Capra organization produced seven pictures for Marshall’s Why We Fight series and many other military films. The Why We Fight films are, in order: Prelude to War (1942), The Nazis Strike (1943), Divide and Conquer (1943), The Battle of Britain (1943), The Battle of Russia (1943), The Battle of China (1944), and War Comes to America (1945).

Each film ends powerfully with a quotation from General Marshall: “No compromise is possible and the victory of the democracies can only be complete with the utter defeat of the war machines of Germany and Japan.”

This quotation, including the underlined “utter defeat,” is shown on screen followed by a ringing Liberty Bell. Over this is superimposed a large letter “V” for Victory accompanied by a stirring soundtrack playing patriotic or military music.

In addition, Capra also produced a series of four films dealing with the military aspects at the end of the war and into peacetime. They were made in 1945, and are titled Two Down and One to Go, Here Is Germany, Know Your Enemy––Japan, and Your Job in Germany.

Eventually the Army changed Capra. The egocentric Hollywood director who wanted his “name above the title” wrote to his officers in 1942, “Most of you were individuals in civilian life. Forget that. You are working for a common cause. Your personal egos and idiosyncrasies are unimportant. There will be no personal credit for your work, either on the screen or in the press. The only press notices we are anxious to read are those of American victories!”

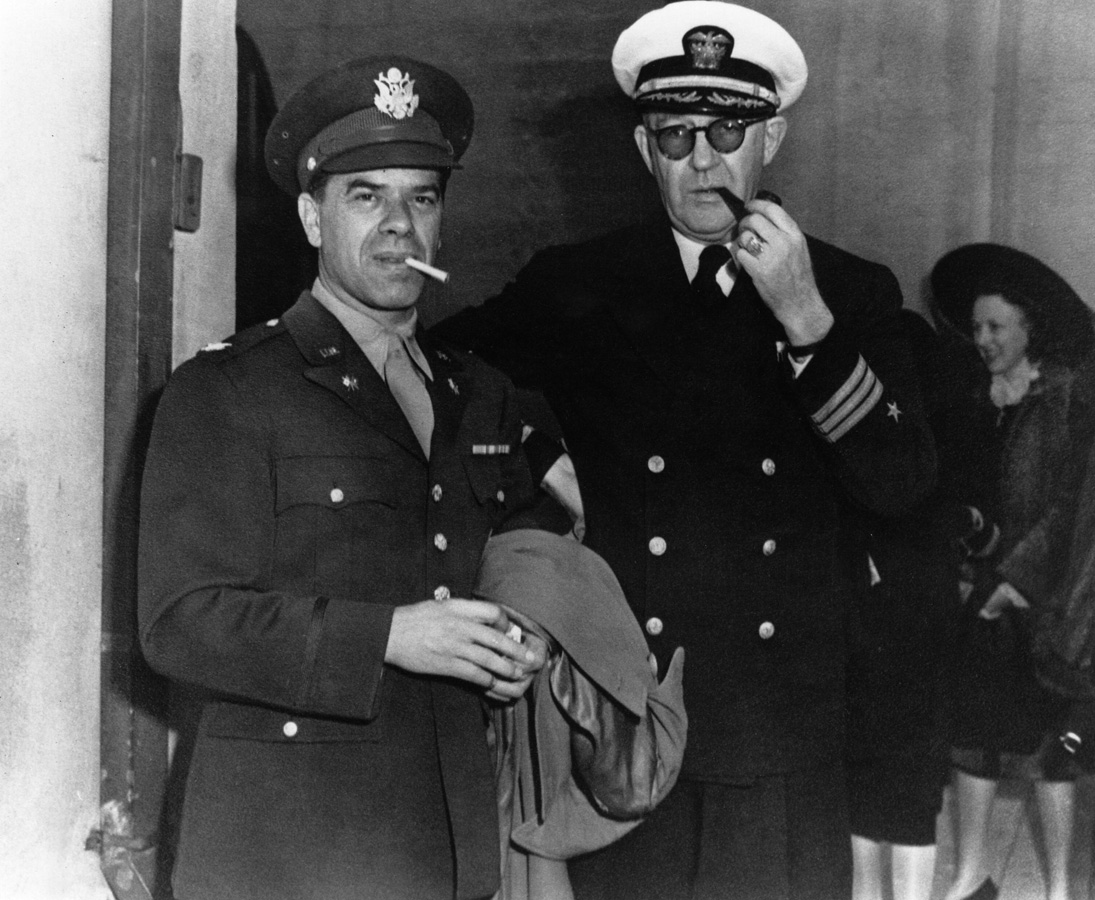

This military Capra surprised many of his Hollywood associates; they had only known the pretentiousness of his Hollywood persona. Brig. Gen. Frank McCarthy, Marshall’s secretary during World War II and later the producer of the 1970 Oscar-winning film Patton, summed up the World War II Capra in a few words: “He was a team player. He displayed no self-interest at all.”

However, Capra’s lack of self-interest would have to change soon. On June 14, 1945, Colonel Capra, the assistant chief of an Army Pictorial Service unit, was emptying his desk because the next day he would be formally discharged from the Army.

His commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Edward Lyman Munson, Jr., unexpectedly came into his office, and told him that General Marshall needed him at once. Capra, expecting more work, complained that he was being discharged; Munson ignored Capra’s complaint, so Capra “high-tailed it” to Marshall’s suite.

He was immediately ushered into Marshall’s private office by Frank McCarthy. What happened next and its final outcome are best put into Capra’s words 26 years after the event.

In The Name Above the Title, he appeared to relive the event: “I … [went into Marshall’s inner office] then stopped as if I had been shot. Facing me and standing at attention was a line of beribboned generals … all were grinning at me. Two Signal Corps photographers raised their cameras.” General Marshall was presenting Capra the Distinguished Service Medal.

Capra continued, “And now General Marshall … is going to pin that great honor on me [Capra’s italics]. Camera bulbs flash … I feel like a bum … I flush with shame … I walk down the hall … like a zombie… [I] go into the first washroom … into a cubicle … lock the door … sit on the toilet seat … and cry like a baby.”

Capra’s discharge from the Army brought on a sudden upsurge in his emotional difficulties, which appeared to have been kept under control because he was active in the Army. It is thought by some that his problems had been kept in cold storage by his knowledge of what he was doing for the American war effort. This cold storage vanished when the war ended.

As if to underscore the loss of all of the creative juices that had been expended during the war, Capra’s postwar films were poorly received. One critic called them “Capra-corn,” while another called them “sentimental and flabby.” Two of these films were remakes of his prewar films. Capra retired from filmmaking after completing Pocket Full of Miracles (1961), a remake of his 1933 production Lady for a Day.

Capra’s later years were difficult. He failed at restarting his film career then suffered a series of minor strokes some years before his death, which put him under 24-hour nursing care. He died in his sleep from a heart attack in his La Quinta, California, home on September 3, 1991, at age 94.

He is still remembered by Americans, who were inspired by his Why We Fight films, as a man who put his heart and soul into his work to help the Allies win the war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments