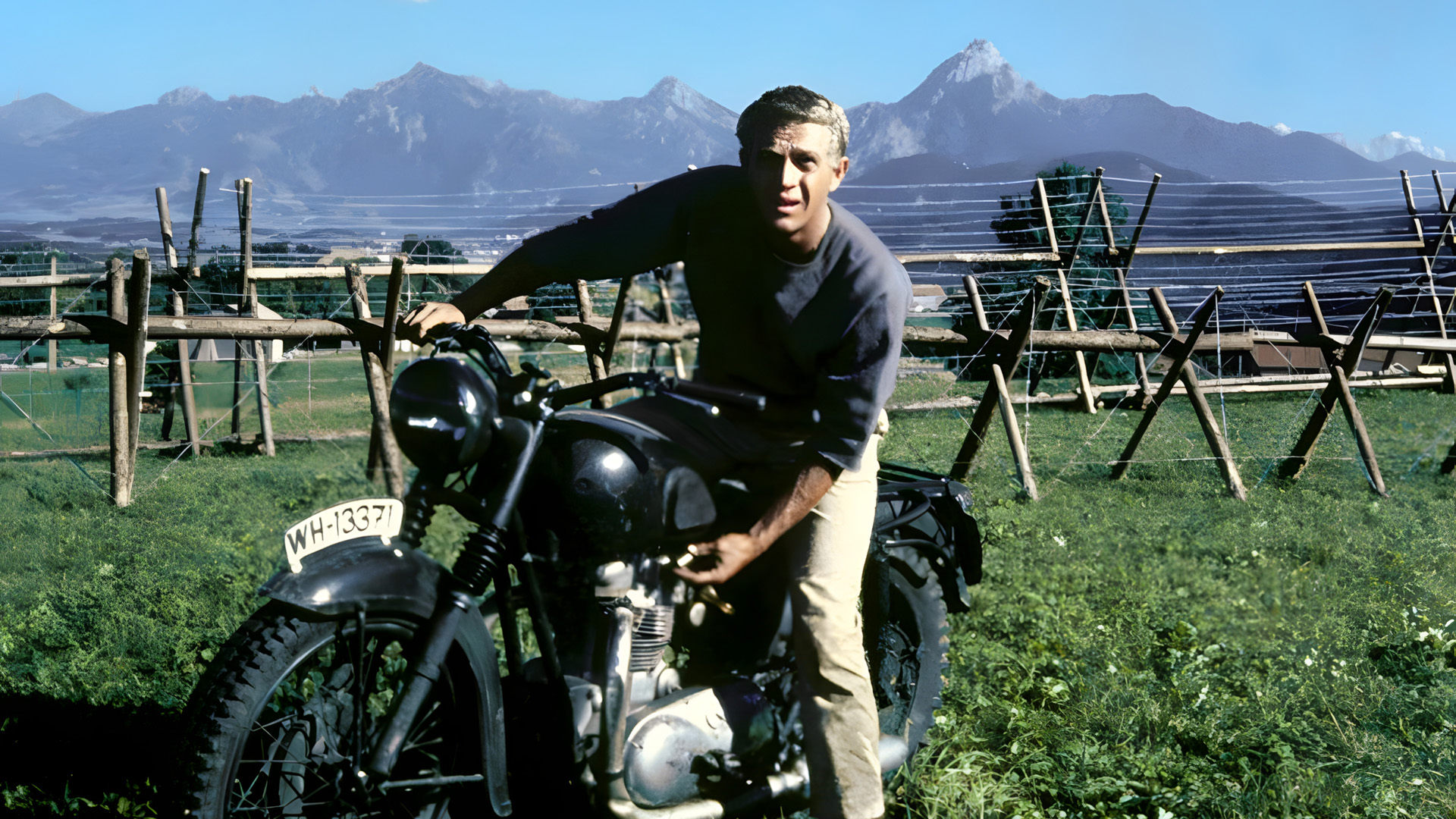

Not long ago I was watching one of my all-time favorite war movies—The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen, James Garner, Richard Attenborough, James Coburn, Charles Bronson, and many others.

If you’re not familiar with it, the movie is a fictionalized account of an actual event: the breakout in March 1944 of Allied prisoners of war from Stalag Luft III near Sagan, Poland, 100 miles east of Berlin.

Despite renewed interest in the subject after the film came out in 1963, the tunnels remained undisturbed over the decades because the camp site was behind the Iron Curtain and the Soviet authorities had no interest in its significance.

But not long ago British archaeologists received permission from the Polish government to excavate it and bring to light its remarkable secrets.

How the breakout was accomplished remains nothing less than astounding. For months some 600 prisoners (10,000 POWs were housed there) worked in the greatest secrecy digging four tunnels (nicknamed “Tom,” “Dick,” “Harry,” and “George”; “George” was begun under seat 13 in the camp theater.) In time, “Harry” became the main escape tunnel and all work was focused on finishing the passageway, over 110 yards long.

To shore up the “Harry” tunnel 30 feet below ground in soft sand, the POWs scavenged 4,000 boards from 90 bunk beds and used 635 mattresses, 62 tables, 34 chairs, and 76 benches. Diggers used stolen shovels, 2,000 knives, and 2,000 spoons. Even a trolley system was built to carry out sand and to move tunnelers back and forth down the tunnel’s length. To provide air to the diggers, a ventilation duct system ingeniously crafted from 1,400 used powdered-milk containers (known as “Klim tins”) was employed.

On the night of the great escape, March 24-25, 1944, 200 preselected prisoners, allocated consecutive numbers, gathered in Hut 104 to make their way down the tunnel, each a few minutes apart. The leaders were dressed in German uniforms or specially tailored civilian outfits crafted by tailors among the prisoners and equipped with compasses, maps, and false identification papers.

Only 76 Allied airmen managed to leave the camp before the alarm was raised when escapee number 77 was spotted emerging outside the wire.

Tragically, only three of the 76 made it to safety. Another 50 were recaptured and executed by firing squad on Hitler’s orders. He was furious after learning about the breach of security, and “Harry” was sealed by the Germans after the audacious breakout.

A couple of years ago, a group of British archaeologists got permission to excavate the prison-camp site and find the tunnels. Using ground-scanning radar, what they found was remarkable; all four tunnels and a treasure trove of artifacts were located.

One of a handful of ex-RAF airmen invited to watch the excavation was Gordie King, a former RAF pilot, who operated the bellows pump providing fresh air on the night of the escape, and who was 140th in line to use “Harry” and therefore missed out.

King said only German-speaking officers were given disguises and papers. He remembered sharing final words with many of the escapees, wishing them luck, and complimenting them on “their impressive disguises. It was quite exciting.” Watching the tunnels being unearthed, though, brought back strong emotions. “This brings back such bittersweet memories,” he said, wiping away tears.

As I’ve said before, the war spawned millions of stories. The story of the Great Escape is one of the most dramatic ones.

—Flint Whitlock, Editor

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments