By Robert Heege

The grim-faced men waiting to take their places in the boats were already chilled to the bone, the winter winds whipping mercilessly through their makeshift, threadbare uniforms as they silently formed up along the icy Pennsylvania riverbank. Many of them used old cloth to plug up the holes in their careworn shoes. Many a man had no shoes at all and had tied filthy strips of tattered rags around their feet to ward off the frigid elements; others stood barefoot in the snow. But not a single one of them uttered a word of complaint.

It was late in the evening of December 25, 1776. Nearly six months had passed since that sweltering July day in Philadelphia when the gentlemen of the self-styled Continental Congress took it upon themselves to speak for everyone in all of the 13 colonies and proclaimed their separatist intentions to a cynical world in their unilateral Declaration of Independence. Now those lofty words were being answered by the standard British response to rebellion in its far-flung provinces: Brown Bess muskets and cannon balls.

It was amid an atmosphere of high hopes that General George Washington, the wealthy 43-year-old gentleman planter from Virginia and veteran of the French and Indian War, had accepted the appointment as commander-in-chief, and in those heady early days, the ranks of volunteers flocking to the banner of what became known as the Continental Army had swelled to some 20,000 citizen-soldiers. But by that December, all that must have seemed like ancient history.

As the year dwindled down to its last few depressing days, the Patriots were down in the dumps. Since then, Washington had failed to carry the day in a single, solitary engagement against his Imperial adversary. To the British forces arrayed against him, for whom the very notion of American liberty sounded like a ridiculous joke, both he and his army of malcontents and country bumpkins were nothing less than a laughingstock. It was easy to see why.

In the months that had followed the proclamation of July 4, the Redcoats had made great sport out of beating the Continentals at every turn, chasing them completely out of Manhattan and Brooklyn, clear across the length of Long Island and the whole of lower New York, only relenting as the winter set in. By that time the British had succeeded in harrying them all the way to the banks of the Delaware River in the frigid precincts of southern Pennsylvania.

Defeat after defeat had taken many of them out of the fight and the fight out of many. Disease, desertion, and death, coupled with limited terms of enlistment, had winnowed their ranks down dramatically by early December. Worse yet, come January 1, when still more enlistments would be up, that dwindling number was poised to drop to fewer than 3,000 weary souls. To keep the infant cause of liberty from dying in its crib, Washington needed to inspire more of his fellow countrymen to answer his call to arms. To achieve that, he needed a fresh approach.

What must have lit up Washington’s brain that freezing December night was the tantalizing fact that on the other side of the river in New Jersey the sleepy little town of Trenton, much to the dismay of nearly all of the townsfolk there, was being forced to provide for the winter quartering of a garrison of paid mercenaries newly arrived from Hesse, a German duchy with family ties to Great Britain’s royal family. Like hired guns, they had been imported to the American colonies for the express purpose of helping to bring the recalcitrant colonials to heel. But there were fewer than 1,500 of them. Moreover, as far as the defenses went, by all accounts their commander, a colonel by the name of Johann Rall, had apparently neglected to erect any.

Rall was a rather obnoxious officer who had sneeringly referred to the Patriot army as a bunch of provincial clowns. He had declared, with typical Teutonic arrogance, that if any of the country rabble dared to show up, the bayonets of his grenadiers would soon send them scurrying away like frightened mice.

Washington was a proud man, and they had laughed at him, hounded him out of New York all the way out into the snowbound Pennsylvanian wilderness. There, beckoning across the water lay Trenton, less than 10 miles away on the other side of the river.

He had let the men have their Christmas, cold comfort though it must have been, and then, late in the evening on Christmas night, taking the bit into his now celebrated teeth, Washington doubled down, risking it all on one brazen roll of the dice upon the Delaware. Under cover of darkness, he gave the order to assemble, tasking Colonel John Glover, a redoubtable old salt from Marblehead, Massachusetts, and the seasoned New England mariners of his 14th Continental Regiment to ready the Durham boats.

Flat-bottomed and double-ended, these sturdy, 60-foot craft with their large sweeps of steering oars at the back, propelled by three to four pole men on outboard walking planks, were a common sight along the Delaware, hauling heavy commercial loads up and down the river. But on this bone-chilling Christmas night, they would be commandeered to ferry a different breed of cargo altogether.

Cannons were dragged painfully up onto larger ferryboats, as were the officer’s horses. The horses, being sensible animals, resisted being loaded onto the creaking wooden planks of the ferries. Then, the sky opened up and it began to rain, even as the temperature continued to plummet. Before long, the rain became sleet and then it started to snow. The wind turned into a gale as a full-fledged Nor’easter blew in. The river was beginning to freeze over.

With numb fingers and frozen feet, Washington’s weather-beaten men, each equipped with 60 rounds of ammunition and three days of meager rations, shouldered arms, filed in, and took their places in the boats. Glover’s pole men, three to a boat, sank the great wooden shafts of their iron-tipped, 18-foot-long setting poles down deep into the muddy bottom beneath the frigid waters of the river and pushed off from the bank. The password for the operation, chosen by their commander himself, swept through the tightly packed ranks like lightning, revealing much about Washington’s somewhat fatalistic state of mind that night: victory or death.

Washington had miscalculated his logistics badly. Expecting to be in New Jersey by 12 am, he was now at the mercy of a freezing North American river in the dead of winter, trying to navigate his way around numerous chunks of jagged ice bobbing all around the wooden plank boards of his open boats.

All these delays wreaked havoc on Washington’s original order of battle. Half of his men, entrusted to Brig. Gen. James Ewing and the Trenton-born Pennsylvanian, Brig. Gen. John Cadwalader, never managed to make the crossing at all. It was almost 3 am by the time the remaining 2,400 of Washington’s army were finally across and standing on the Jersey side of the river, but their physical trials were far from over. Trenton was still nine freezing, snowdrift-ridden miles away from their landing zone over next to nonexistent country roads, and they would have to manage a near silent march every miserable step of the way there.

Nearing their objective, Washington broke with the standard military doctrine of the day, effectively splitting his command. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, a Rhode Islander of Quaker stock, would lead one column into Trenton from the north, neutralizing any Hessian assets deployed along the route into town. Another Washington favorite, the Irish Brig. Gen. John Sullivan, a first generation Yankee from New Hampshire, would enter Trenton from the south and west.

Up and down the length of the column, under the first rays of dawn, rode Washington, accompanying Greene’s division, exhorting his troops on. As for his Hessian counterpart, after spending Christmas night warm and dry in his commandeered quarters, playing cards by the fire and draining a couple of bottles of wine by some accounts, a blissfully unconcerned Oberst Rall had bid his officers a Merry Christmas and padded off to bed.

In those days, Trenton had two main thoroughfares, christened, in less contentious times, King Street and Queen Street. It was at a small copper shop about a mile outside of town on Pennington Road, where the Hessians had set up a small command post that history was made at about 8 am on December 26. Hessian Lieutenant Andreas von Wiederholt stepped out of the front door of the shop just as George Washington came galloping into view at the head of his troops. The young lieutenant shouted a warning to his men, who came pouring out of the shop, bayonets bristling.

In the blink of an eye, the battle was on, with the Hessians somehow managing to prime their muskets and fire off a volley, only to find themselves subjected in return to three withering fusillades from Washington’s infantrymen, who proceeded to cut them down like cordwood. As the musket balls whistled through the air, other Hessian detachments converged on the area, including some elements of the Alt von Lossberg Regiment. and, Regrouping on the high ground on the northern outskirts of Trenton, the Hessians returned fire as von Wiederholt led an organized retreat.

As they fell back on the town, several Hessian Guard Companies quickly entered the fray, providing their retreating kinsmen with covering fire against the deadly accuracy of the Colonial crack shots, who were now picking them off one by one.

The Hessian retreat toward the center of town actually served to effectuate a major component of Washington’s original battle plan, as it left the nearby River Road completely in the hands of the Continentals. Quickly exploiting the situation, Washington, taking up a commanding position atop a small hillside, dispatched an infantry formation to block any attempt the enemy might make to escape toward Princeton. He directed his artillerymen to move with all possible speed and bring their guns into action before the still sleepy Hessians had a chance to check them.

Moments later, Colonel Henry Knox, a portly but daring diehard from Boston, Massachusetts, had his artillerymen wheeling some of their highly prized cannons into position at the end of King and Queen Streets. Among them was a young captain named Alexander Hamilton.

Meanwhile, Sullivan and his column rushed forward from the South, seizing the sole crossing over the Assunpink, the creek that could have provided a way out for the Hessians. In an example of strategic battlefield coordination remarkable for its day, the Irishman paced his march into Trenton, taking pains to make certain that Greene and his column had been given sufficient time to dislodge any Hessians deployed at the northern approaches to the town.

Coming up the River Road, the vanguard of Sullivan’s division stormed its way into Trenton. Almost immediately they ran into a detachment of about a dozen Hessians, part of a company of about 50 Jaegers quartered in and around a private residence. Lieutenant Wilhelm von Grothausen ordered his men into action, but seeing the rest of Sullivan’s column now swarming into Trenton, gave the lieutenant pause. After a somewhat desultory exchange of a single volley of lead, he ordered his men to pull back, whereupon the entire complement turned tail. Several of them joined 18 Redcoats of the Queen’s 16th Light Dragoons stationed nearby on the small bridge over the Assunpink, who upon Sullivan’s arrival had proceeded to dive headlong into this tributary of the Delaware in a frantic effort to escape from the battle zone.

By this time, Greene and his forces, including Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer’s brigade, were advancing from the north end of town. As the two infantry divisions now pushed forward toward each other, American cannon fire began raining down on the Hessians. This cannonade came from the Pennsylvania side of the river, courtesy of the emboldened Rebels stuck observing the action from the opposite bank.

The Hessians, however, were not ready to pack it in quite yet. By now, Colonel Rall was out of his bed. Having been roused from his sleep by the sudden crackle of all that musket fire, he was appalled when informed that the crossroads at the upper ends of King and Queen Streets, the center of the town, was already in Rebel hands. His instinctive reaction was to immediately counterattack. Answering the call to arms, no less than three regiments of renowned European infantry shook off the morning doldrums and snapped into action, assuming battle formation with clockwork Germanic efficiency.

Lining up at the lower end of Queen Street, the venerable Alt von Lossberg regiment steeled itself for a fight. Simultaneously, the grenadiers of the Rall regiment, so named for its commander, made ready at the lower end of King Street and awaited orders. The Fusiliers of the von Knyphausen Regiment were held in reserve to reinforce the Rall regiment on King Street, if needed.

Rall’s strategy was simple, straightforward, and bloody-minded. With a regiment of prized Hessian infantry now poised on each of the two high streets, and in accordance with the accepted military doctrine of the period, the colonel ordered the cream of his command to march in lock-step up the length of Queen and King Streets.

Rall’s single-minded goal was to drive the Rebels off and take back the center of the town. The problem was that Washington had foreseen this obvious response from his Hessian counterpart and made sure Knox was in position to thwart it.

Advancing doggedly up King and Queen Streets, the Hessians marched straight into the teeth of the American guns as Knox and his artillerymen opened up on them. At last, after a hellish half year, it was the Continentals who were dishing it out, and the forces of empire were on the receiving end.

Ordered to capture the American cannons, Rall’s grenadiers pressed grimly on, shoulder to shoulder through the acrid, blue-gray haze of gunpowder, trooping forward up King Street through shot and shell. Their uniforms were spattered with the blood and gore of their fallen comrades as bits of brain and splintered bone rent the chill morning air.

As if that were not enough, scores of Mercer’s riflemen had gotten into the houses and shops along the route, taken up concealed positions, and begun firing at will into the tightly packed Hessian formations, turning King Street into a gauntlet of death. Rall tried to get some of his own artillery into the fight, sending a brace of three pounders up the street, but after somehow managing to fire off a dozen jittery salvos, they were blasted out of commission by Knox and his boys at the upper end of the street and Mercer’s men sniping at them from the houses.

On Queen Street, the Hessians fared no better, blasted by Rebel cannons and picked off by an enemy raised on shooting turkeys and not too proud to take cover. There, too, the Rebels fired away with impunity at their hapless opponents.

Military discipline, even the German kind, will eventually give way in the face of such an onslaught and the Hessians began to waver. The sight of the Rebels clambering over their fallen comrades in the Hessian gun crews to capture their cannons and prepare to bombard them with their own artillery was simply too much for the stunned soldiers. All along King and Queen Streets, the Hessians broke ranks and fled, pursued toward the fields on the outskirts of town.

In the fog of war, the Knyphausen Regiment, having been held back in reserve, became separated from the rest of their kinsmen. Still caught in Trenton, many found that their muskets were misfiring because they had let their powder get too damp. Seeing this, Sullivan, unwilling to simply continue blasting away at his helpless foe, sent his men rushing down the street in a howling bayonet charge. He led several of his men in hot pursuit down toward the creek to scotch any hope of a Hessian retreat. There, along the Assunpink, the woefully unlucky Knyphausens dithered for several tense minutes before finally throwing down their useless muskets and raising their hands in surrender.

But Colonel Rall was not through yet. Incapable of accepting defeat, he re-grouped what was left of his command in a field just outside of Trenton, ordered his regimental fifes and drums to play a tune, and ordered his grenadiers forward in a futile attempt to retake Trenton. Despite being shot at from three sides, Ralls’ infantrymen stubbornly advanced back into town and up the length of King Street, through artillery bombardment and a merciless fusillade, and succeeded in retaking some of their cannons. But Knox would have none of it and after a brief but tenacious struggle soon drove them off again, once more training the cannons back onto the advancing Hessian columns.

At that point, some of the townsfolk rushed from their homes and joined the Rebel army in fending off their uninvited guests’ attempted counterthrust. Hessian unit cohesion again began to falter. Rall was many things, but he was no coward. He was there, in the midst of the melee, shouting himself hoarse, still desperately attempting to rally his men forward and press the attack when a clutch of Rebel musket balls suddenly slammed into his medal-bedecked chest. He fell to the ground and died later that day. An unheeded Loyalist message, possibly unread, warning ominously of a dangerous number of Rebels being spotted recently in the vicinity was later found on his lifeless body.

Deprived of their commander, the Hessians suddenly seemed to be at a complete loss as to what to do. Seeing this, Washington spurred his mount and galloped down from his hilltop position, rallying his men, leading them forward in a final charge that drove the broken Hessians back out of town into an orchard. Surrounded by the very men they had once derided as clownish buffoons and stung by the humiliating taunts of several of the jeering citizens of Trenton, what remained of the proud Hessian regiments, more than 900 souls in all, gave up at last, lowered their colors, and meekly surrendered.

The battle for Trenton had lasted scarcely half an hour. When the fighting was over, 22 Hessians were dead. Another 92 of their wounded comrades lay writhing in agony up and down the streets of the quaint little Colonial town. Washington had not lost a single man during the attack. He had scored his victory at a cost of a mere five wounded.

The Continentals had taken Trenton but they could not hold it. The forces of the British Crown would certainly seek to return this insult with a vengeance, and Washington knew that if British reinforcements should suddenly appear in strength, the Continentals would fare no better than the Hessians. Because of the threat of enemy reinforcements, Washington decided return to the relative safety of the Pennsylvania pines. But news travels fast, and on December 30, buoyed by his success, Washington returned to New Jersey with a rejuvenated army. This time, Ewing and Cadwalader managed to make the trip.

At this moment, in the British bastion of New York City, General Lord Charles Cornwallis was appalled when he was informed that his leave was summarily cancelled. Washington’s little triumph had just cost him his passage home to England to see the wife. On New Year’s Day 1777, a furious Cornwallis was galloping the 50 miles to Princeton, New Jersey. Barely a day later, he was at the head of an army speeding south to punish Washington for his audacity.

Meanwhile, Washington had been working feverishly to capitalize on the propaganda value of his victory at Trenton to gather more fresh recruits and strive to retain the veterans whose one-year enlistments were up, exhorting them to keep faith with him for a further six weeks, and throwing in a ten dollar bounty to sweeten the bargain. His efforts bore fruit, and by January 2 Washington could boast more than 5,000 men in the ranks, though most of them were barely trained. Ready or not, they were about to receive their baptism of fire. That very evening, Cornwallis and his army arrived.

With night falling, British advance units probing the woods in the vicinity of the Assunpink traded shots with Rebel pickets along the creek, culminating in a textbook British move to seize the little bridge. But the Rebels, emboldened by their Lilliputian victory over the Hessians, defiantly stood their ground, successfully fending off attempts to push them off the bridge as darkness descended.

Cornwallis remained calm and collected. Owing to the lateness of the hour, his apparently fatigued Lordship halted the bulk of his columns about a half mile outside of Trenton and made camp. With the frozen Delaware still seemingly impassable, Cornwallis considered his foe to be neatly bottled up there on the banks. Indeed, his scouts reported that Washington and his Rebel army were camped beside the ice bound river.

Pointing a languid finger toward the lights of the Rebels’ campfires, clearly visible in the dark wintry night, Cornwallis cheerily reassured his officers that after a six-month chase across three of the 13 colonies, the wily Washington was truly trapped at last. Washington would be just as dead come morning when, by the light of day, they would march over and wipe out his paltry command after a good night’s sleep.

By dawn, Cornwallis must have wanted to kick himself in the pants. At about 1 am, even as the Rebel campfires continued to flicker and beckon, stoked, it turned out, by 500 conspicuously merrymaking men tasked with this purpose to complete the deception, a canny Washington had his men wrapping rags around their cannon and wagon wheels, and even around the hooves of their officers’ horses as they made a stealthy getaway under Cornwallis’ nose.

Arriving at Trenton early that morning, January 3, at the head of his mighty host, Cornwallis was dumbfounded to discover that his nemesis was nowhere to be found. While the British slept, Washington and his men had circled around their entire army in the dead of night and escaped the deadly trap. Marching north in silence through the frozen dark, come sun up they were a scant two miles from Cornwallis’ original starting point at Princeton.

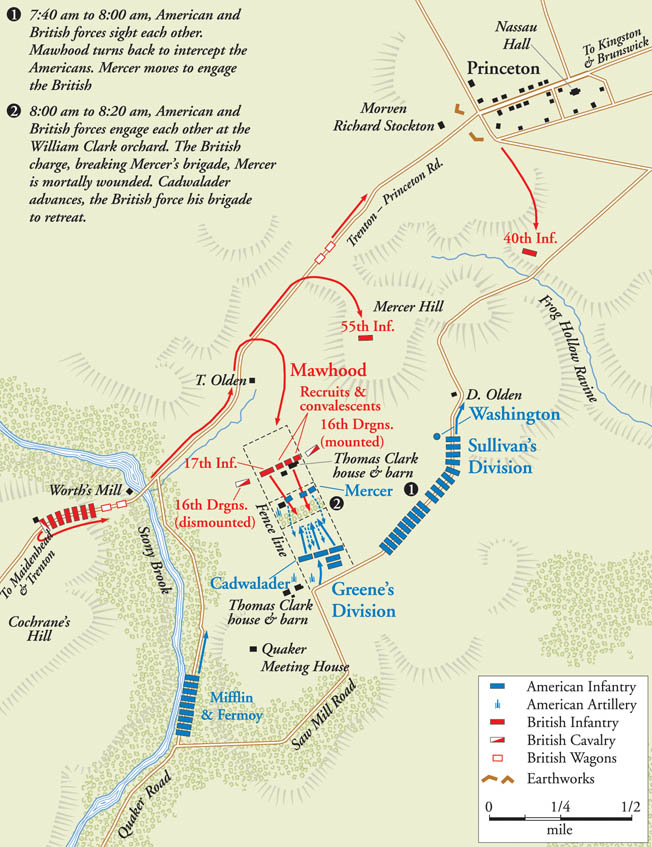

Princeton, which had previously been chock full of British Regulars, was now only lightly defended, garrisoned by about 1,200 Redcoats under the command of Lt. Col. Charles Mawhood, whom Cornwallis had left behind before setting off to confront Washington at Trenton.

Urging his men northward through the wooded pathways, Washington reached Stony Brook, a small stream, which the Continentals followed for a full mile to the point where it abutted the Post Road, the vital commercial artery running north and south between Princeton and Trenton.

Loath to be caught out in the open in broad daylight, Washington quickly sent his men scurrying over and across the nearby fields of William Clark’s farm, which lay just to the right of the road. To Washington’s great good luck, there was another unmarked pathway of sorts running through Farmer Clark’s fields that not only led straight into town but could not be seen from the nearby Post Road. It was also completely undefended.

Undetected, Washington was now only about a mile and a half away from Princeton, his command all but invisible as his men quietly formed up on the dirt track that the farmers used to bring their vegetables to market. But by this time, it was already 7:30. He knew that back in Trenton, Cornwallis was surely standing beside the Delaware by now, seeing red and shaking his fist.

Washington knew he had to act fast. He turned to his old friend and comrade from the French and Indian War, the Scotsman Mercer, whose martial talents had proved so invaluable at Trenton. Once the regimental surgeon to Bonnie Prince Charlie during Scotland’s own abortive rebellion, Mercer had fled to the colonies and made a new life for himself in Fredericksburg, Virginia. The 51-year-old clergyman’s son received orders to take 350 men back to the wooden bridge over Stony Brook, deny the enemy its potential use, and buy Washington some badly needed time.

Still unaware that he was about to be attacked, Mawhood was dutifully following Cornwallis’ previously issued orders to tip the scales, dispatching two additional regiments, the 17th and the 55th Regiments of Foot, to reinforce his lordship at Trenton that morning, leaving a single regiment, the men of the 40th to safeguard Princeton in their absence.

By 8 am Mawhood and his men were on the move. They had only just left Princeton, making for the bridge at Stony Brook. But as the Redcoats marching through the Jersey pines crested the top of a small hill just to the south, they spotted the Continentals below. Mawhood immediately wheeled his infantrymen around and made a mad scramble back toward the garrison.

Mercer’s reaction was equally swift. Seeing Mawhood on the move, he hastened to cut him off and protect Washington’s main force by attacking Mawhood’s columns from the rear. By now, the attack on Princeton was already on, with Sullivan and his entire division, two brigades of hardy diehards in the van, charging down the dirt track from Clark’s Farm, followed close behind by two more brigades, the first of these under the command of Cadwalader, absent at Trenton, now getting in on the action at last. The other was a brigade of Rhode Islanders led by an attorney from Massachusetts named Colonel Daniel Hitchcock.

As for Mawhood, Mercer, and their deadly chase, exactly which one was the fox and which, the hound, was in doubt. Mercer, despairing of catching and cutting off Mawhood’s Redcoats short of Princeton, peeled off to join Sullivan’s forces in the main attack. Mawhood had become aware that a Rebel column had been coming up behind him in close pursuit, but seeing them suddenly breaking off the chase and making a beeline toward Clark Farm must have struck him like lightning. Everybody in Princeton knew about the path through the farmer’s fields.

Sending the main body of his infantry forward to reinforce the Princeton garrison, Mawhood now turned the tables, siphoning off the 17th of Foot and elements of the 55th, a brace of artillery pieces, and about 50 cavalrymen, and sent them chasing after Mercer.

They caught up with him in Farmer Clark’s orchard and unleashed a volley, but the notoriously inaccurate Brown Bess muskets missed their marks, sending their leaden payloads flying high over the Rebels’ heads. Mercer shouted to his men to get into proper battle formation and advance on the Redcoats before they could reload, but as the Rebels looked on in horror, still more scarlet-clad infantrymen arrived, backed up by the gleaming bronze cannons of the Royal Artillery.

Taking cover behind a nearby fence, Mercer ordered his riflemen to open fire. The British responded with another volley of their own, and back and forth it went. For eight murderous minutes the two sides traded lead with each other. But Mercer’s rifles, though more accurate, took longer to reload than the British muskets, and there were so many more of them.

The Redcoats, trained to withstand the brutal psychology of such encounters, soon had the upper hand. Some of the Rebels did not even have a bayonet at the end of their muskets. Barely trained farm boys fumbling their weapons with trembling hands, they seemed close to panic. Seeing this, Mawhood contemptuously ordered a bayonet charge.

The Rebels broke and fled, all except Mercer and his loyal second, Colonel John Haslet of the 1st Delaware Continentals. There in the orchard, the stubborn Scot stood his ground. Haslet, at his general’s side, implored the fleeing men to stand fast. He received a musket ball in the head for his trouble and was dead before he hit the ground.

Calling mercer a damned Rebel, the British shouted at him to surrender. Mercer spat at the idea and, asking for no quarter, none was given. The Redcoats who ran him through with their bayonets were ecstatic. They thought they had just killed Washington.

Out for blood, the Redcoats were close on the heels of the fleeing survivors when Rebel and Redcoat alike literally ran straight into Cadwalader’s Pennsylvania militiamen as they came blundering out of the nearby woods.

For several moments, chaos reigned on the battlefield. Mawhood quickly regrouped and got his infantrymen into a proper battle line. Cadwalader attempted to do the same, but his men were so completely unnerved by the sight of British steel and the spectacle of so many of their comrades running past them down the hill that they started to turn tail and follow them.

The battle for Princeton was quickly devolving into a pandemonium. At this moment, Sullivan’s assault force which was directly attacking the Princeton garrison was also starting to lose momentum, bogged down by a determined effort by elements of the 55th of Foot, now rushing to the aid of the town’s defenders, the 40th.

Just then Washington came galloping up over the hill, into the very midst of Cadwalader’s unraveling, stampeding command. Following in his wake were the veteran Virginia Continentals and the deadly riflemen of Colonel Edward Hand, a 32-year-old, Irish-born physician turned revolutionary.

Washington immediately directed Hands’ riflemen and his fellow Virginians onto the high ground to their right. Then, gripping the reins, he galloped out in front between the enemy and his own tentatively advancing troops, heading off the human wave of demoralized yeomen farmers like a cattleman corralling his flock.

Waving his hat like a field marshal’s baton, Washington got them in line. There were so many musket balls whizzing past him, his own horse hesitated to take another step. With less than 90 feet between the two sides, Washington gave the order to fire.

It was as if both armies jumped to his stern command as a deadly blizzard of cannon fire and musket balls erupted from both sides. Lead flew in every direction. The entire battlefield was engulfed in a thick cloud of sulfurous smoke.

One of Washington’s officers buried his head in his hat, convinced he had just seen his fearless commander blown to bits. But as the billows of spent gunpowder wafted away in the wintry New Jersey breeze, there was Washington, miraculously unharmed, urging his troops onward with a majestic sweep of his arm.

Answering the call, a battle line of Hitchcock’s flint-hard New England militiamen went forward, moving to outflank the British right, while Edward Hand used his sharp-shooting riflemen to deadly effect, creating great, gory gaps in their formations until the thin red line of British infantrymen was up to their knees in the blood of their fallen comrades. Then the Continental cannons unleashed salvos of grapeshot, bombarding the British with a deadly hail of hot metal. The British line began to buckle. The New Englanders surged forward.

It was the Redcoats’ turn to give ground as more and more of the now emboldened Continentals came charging across the field. In danger of being overwhelmed, Mawhood reluctantly ordered a fighting retreat toward the Post Road. Washington had been right to worry about the little bridge over Stony Brook. After fixing bayonets, Mawhood led a wild charge that broke past startled Rebel pickets. Screaming like banshees, they scampered over the wooden planks to the other side, leaving a company of Dragoons behind to cover their timely escape.

As for the rest of Mawhood’s command, their position deteriorated rapidly as Sullivan’s Continentals began a renewed effort to capture their prize. The British 40th redeployed to a stronger defensive position on the northern crest of a small hillside just outside of the town. The 55th formed a defensive line to their immediate left. But as defensive positions go, the slope made for paltry high ground, and Sullivan’s men had no difficulty in charging straight up it.

Attacking in force, they kept coming on, leaving the Redcoats with no choice but to retire and make their final stand behind the breastworks they had thrown up in front of the town. But the Continentals, undaunted by volleys of musketry, all but hurled themselves at the barricade, overrunning the breastworks as if it were so many matchsticks. Their position untenable, the British withdrew into the town and, losing any semblance of unit cohesion began to scatter.

Most of them tried to get clear of the town, hoping to rejoin the rest of Cornwallis’ army and live to fight another day. Approximately 300 of them simply went to ground, hiding anywhere they could. Several locked themselves inside Nassau Hall at the College of New Jersey. They were eventually coaxed out by a group of artillerymen led by Alexander Hamilton, who had only recently applied to the college. Denied entry because he had asked to be allowed the privilege of studying at his own pace, Hamilton now found himself in the unique position of being able to lob cannon balls at the college that had rejected him. After a brief bombardment, white flags appeared at the upper windows, and the officers inside agreed to come out and surrender. In less than an hour, the Battle of Princeton was fought and won.

Having secured a second victory, Washington considered making a run on New Brunswick and the 70,000 pounds sterling in the British Army pay chest there, but wisely decided to put some distance between himself and his nemesis as the worsening weather set in. He simply was not strong enough to face off against the soon to return Cornwallis, at least at that point in the war. Washington would spend most of the next four years eluding his grasp, making a habit of vexing his aristocratic adversary and avoiding a direct showdown until he was ready, with the help of the French, at Yorktown in 1781.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments