By Nathan N. Prefer

Most students of World War II know that there were five invasion beaches included in Operation Overlord, the invasion of northwestern Europe, on June 6, 1944. There are numerous writings concerning Omaha Beach, where the 1st and 29th U.S. Infantry Divisions suffered heavily at the hands of the German defenders. The successful landings by the 4th U.S. Infantry Division at Utah Beach are also well covered. But far less has been written about the other North American beachhead that day, Juno Beach, which was assigned to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade.

When Great Britain was drawn into World War II in September 1939, her various dominion nations were drawn in as well. Australia, Canada, India, and New Zealand immediately offered troops in defense of the British Empire. Australian, Indian, South African, and New Zealand troops were to distinguish themselves in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and later in the Pacific and Far East. But Canada’s troops were destined for the United Kingdom itself, originally to defend the islands against the very real threat of a German invasion after the fall of France.

But Germany turned east instead, and Canadian troops languished in England training and preparing for operations that never seemed to materialize. The Canadians, who had earned a reputation as excellent combat soldiers in World War I, were anxious to participate in active operations. One result of this impatience was the assignment of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division to the disastrous raid on the French port town of Dieppe, Operation Jubilee, which savaged that division in August 1942.

To placate the Canadians and bolster his own preferences for operating in the Mediterranean, British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill “invited” the Canadian government to commit forces to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. As a result, the Canadian I Corps, consisting of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and supporting units, was sent to the Mediterranean and participated in the invasion of Sicily and the Italian campaign. Later, the 5th Canadian Armored Division would join the Canadian I Corps in Italy.

The decimated 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions remained in England, training for the expected cross-Channel invasion that was to come sooner or later. Soon, another Canadian formation, the 4th Armored Division, was established in England. These were all within the First Canadian Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Andrew McNaughton. In July 1943, General McNaughton advised the commanders involved that the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division should begin assault training for the possible inclusion in the cross-Channel invasion assault force. With the departure of the Canadian I Corps to Italy, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was transferred to the command of the British I Corps for assault training.

In January 1944, the senior officers who would command the cross-Channel attack arrived in England and reviewed the tentative plans for the invasion. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the overall commander, and Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, the ground forces commander, agreed that the invasion forces needed to be strengthened to ensure the establishment of a beachhead. One of the forces added to the Allied invasion contingent was the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division.

Commanding that division was Maj. Gen. Rod F.L. Keller. Born October 2, 1900, he was barely 42 years old when he was promoted from command of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade to lead the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. He was the youngest division commander in the Canadian Army at that time. Born in England, he had been raised in British Columbia and had graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada in 1920. He served in Canada’s Permanent Active Militia in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Battalion in Winnipeg. His outstanding service led him to be selected for the prestigious British Staff College at Camberley, assuring him of a fast track to promotion to higher rank. Those who served with him later described him as “young and energetic … a forceful leader whose judgment can be relied upon” and “very much a spit and polish officer who cut quite a figure in his battle dress.” Appointed to command the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on September 8, 1942, he had developed a close relationship with his command. His quartermaster general, Lt. Col. Ernest Côté, remembered, “He cared for his division and was sensitive to any slight on its reputation. He was a very proud man and always on top of the division’s training.”

Canadian units followed the British Army’s structure. In the 1944-1945 period, British and Commonwealth infantry divisions consisted of a division headquarters with three infantry brigades under its command. Each brigade contained three infantry battalions, making them similar to the U.S. Army’s three-regiment divisional structure. The division also included a reconnaissance regiment, three field artillery regiments, an antitank regiment, and a light antiaircraft regiment, each of which were equivalent in size to a U.S. Army battalion. Additionally, each division had an engineer component divided into three field companies plus one field park company. The total number of officers (870) and enlisted personnel (17,477) in the British infantry division was 18,347, slightly larger than the standard American infantry division of the period. Armament included 1,262 light machine guns, 40 medium machine guns, 359 mortars, 72 25-pound field artillery guns, 110 antitank guns, and 125 antiaircraft guns. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, though, had recently converted its artillery battalions to the American M7 self-propelled 105mm gun commonly known as the “Priest,” a reference to its pulpit-like machine-gun mount.

The standard maneuver element of both the British and American infantry divisions was the infantry battalion. In the British organization, the infantry battalion consisted of a headquarters company, a support company, and three rifle companies, nearly identical to the American infantry battalion. There were, however, some differences. The headquarters company consisted of a signals platoon and an administrative platoon. The support company, like the heavy weapons company of the American infantry battalion, included a mortar platoon and a carrier-mounted Bren machine-gun platoon. But the British support company also included a platoon each of 6-pound antitank guns and an assault pioneer (engineers) platoon. The rifle companies had three rifle platoons, each consisting of an officer and 36 enlisted personnel and including two light 2-inch mortars, while platoon headquarters included a light machine-gun squad. The division’s 3,347 vehicles included 595 armored tracked carriers, 63 armored cars, and 1,937 trucks of various sizes.

Those independent armored brigades not belonging to an armored division like Brigadier R.A. Wyman’s 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade consisted of three armored regiments and associated support and signal services. They numbered 3,400 officers and men and contained 1,200 vehicles, including 190 medium tanks and 33 light tanks. Nearly all these brigades were armed with the American M4 Sherman medium tank and the American M5 Stuart light tank. Unlike American combat commands, they contained no infantry but were trained to operate in cooperation with infantry divisions. By the time of the invasion, they were also expected to be able to cooperate with armored divisions.

The Canadians also had a further addition for D-Day: the 2nd Royal Marine Assault Squadron. These British Royal Marines were armed with 32 95mm howitzers mounted on Centaur tanks. These guns were capable of both direct and indirect fire support during the critical stages of the landing. The Royal Artillery’s 62nd Antitank Regiment, armed with 48 antitank guns, was also to land with the division on D-Day, adding firepower to the organic 3rd Antitank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery. In total, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division had more guns assigned to it on D-Day than any other assaulting formation.

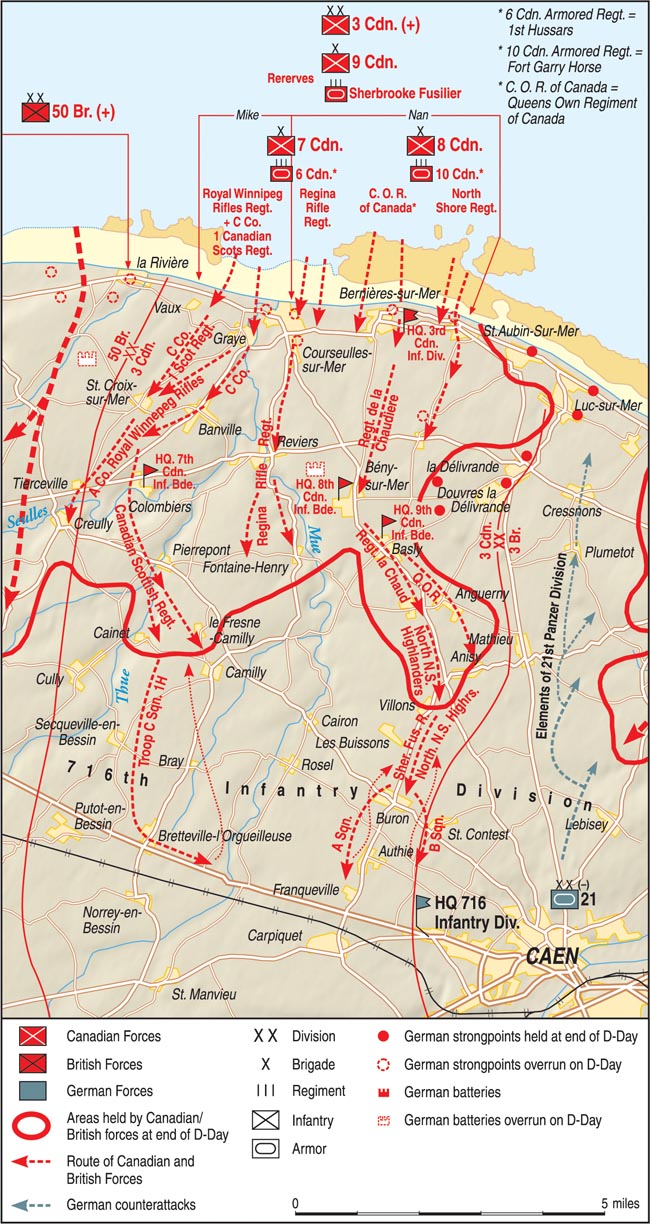

The British Second Army was to assault the Normandy coast alongside the American First Army. The British were assigned three assault beaches, codenamed Gold, Juno, and Sword. Lt. Gen. J.T. Crocker’s I (British) Corps, with the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade under its command, was assigned the center beach, Juno. That beach was a five-mile strip of low, flat, sandy countryside. It ran from the town of St. Aubin-sur-Mer in the east to the Château Vaux a mile west of the Seulles River. Two small villages, Berniêres-sur-Mer and Courseulles-sur-Mer, were located within that beachhead area. In places, there were 10-foot-high dunes behind the beaches. The villages along the beach were all protected by concrete seawalls that would prove an obstacle to assault troops. So too would the underwater offshore reef that ran in front of the beach.

The assault plan was a basic two-up-front, one-in-reserve plan. Brigadier Harry W. Foster’s 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade would land west of the Seulles River with a battalion landing in front of Courseulles. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, reinforced with a rifle company from the 1st Battalion, Canadian Scottish Regiment, would land at the river, while the Regina Rifle Regiment took on Courseulles. The balance of the 1st Battalion, Canadian Scottish Regiment would be in brigade reserve. These troops would be supported by the tanks of the 1st Hussars (6th Armored) Regiment, 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade and the 12th and 13th Field (Artillery) Regiments. The adjoining assault brigade, Brigadier K.G. Blackader’s 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade, would land The Queen’s Own Regiment of Canada at Berniéres and The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment at St. Aubin. They were to be supported by the Fort Garry Horse (10th Armored Regiment) and the 14th Field (Artillery) Regiment along with the attached 19th Field (Artillery) Regiment. The third battalion of the brigade, Le Régiment de la Chaudiére, would be in reserve.

To cover a wide gap between the Canadian beaches and the adjoining British 3rd Infantry Division on Sword Beach, General Keller was given the attached 48th (Royal Marine) Commando. Their job was to capture the town of Langrune-sur-Mer and then link up with another commando group coming from Sword Beach. Brigadier D.G. Cunningham’s 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade was in reserve, scheduled to come ashore once the beach was secured.

Manning Adolf Hitler’s “Atlantic Wall” along Juno Beach was the German 716th Infantry Division. Formed from older personnel in April 1941, the division had been sent directly to the Caen area in Normandy and remained there until D-Day. It consisted of the 726th and 736th Infantry Regiments and the 716th Artillery Battalion along with the usual supporting elements. The Canadians would face the 736th Infantry Regiment and one of these supporting elements, the 441st Ost (East) Battalion made up of Eastern European conscripts and former Russian prisoners of war, volunteers of doubtful loyalty to Germany. All personnel had been trained in coast defense tactics, some for years, but the division was not highly rated by Allied intelligence. It was believed to be overstrength, normally at 13,000, with the attachment of some Ost Battalions.

Nevertheless, the least motivated troops sheltered within concrete emplacements and, armed with automatic weapons, mortars, and artillery, had often given a good account of themselves against attacking troops coming at them across open beaches with little or no protection. Allied intelligence had identified at least nine such strongpoints along Juno Beach. These strongpoints were backed up by fieldworks that protected additional machine guns and mortars behind the beach itself. Finally, Allied intelligence reported a first-class assault division, the new 12th SS Panzer (Hitler Youth) Division, within a day’s march of the beach and, even worse, the presence of the experienced and fully operational 21st Panzer Division less than half a day’s travel from Juno Beach. Some of the latter’s artillery command were within supporting distance of Juno Beach on D-Day.

On a cloudy morning with a wind from the west-northwest and moderate waves reaching nearly a foot high, the bombardment of Juno Beach began. As would happen on other beaches, particularly Omaha Beach in the American sector, the aerial bombardment largely missed Juno Beach due to cloud cover and increasing dust from the bombing itself. But planners had foreseen such a possibility and planned what the British command called “drenching fire.” This was to be an overwhelming naval barrage designed to neutralize the German defenses. General Keller would later report that this was “accurate and sustained.” But the naval guns did not have the power to destroy the thick concrete defenses built by the Germans on the beach. Instead, it was hoped that the bombardment would stun those defenders long enough for the Canadian infantry to get close enough to destroy them once the barrage lifted.

Eleven British and Canadian destroyers and several gunboats maintained this fire directed at the identified strongpoints along the beach. The division’s field artillery battalions, aboard landing craft approaching the beach, also fired on the strongpoints as the craft sailed at a steady six knots toward that same beach. Each of the “Priests,” for example, fired 120 rounds over the heads of the infantry while they approached the beach. Again, General Keller believed that they “put on the best shoot that they ever did.”

Despite the impressive sound and fury of the bombardment, little was accomplished. A post-battle assessment by a special British observer group reported, “Except in a few isolated cases where weapons had been put out of action by direct hits through the embrasures (it is not possible to establish the actual time when these were made) the beach defenses were unaffected by the fire preparation. Reports have been received from all except S Beach that the defenses generally were still in action when the fire plan had been completed, and while troops were being landed. Any neutralization during the run in may have been due either to the morale effect of the bombardment or to the fact that until the leading waves were close in shore the defenses could not bear or had insufficient range. All evidence shows that the defenses were NOT destroyed.”

Because of tide and beach conditions, the landing times for each assault beach varied slightly. On Juno Beach, the conditions, including the need for sufficient water over the offshore reef to allow the assault craft to sail over it, made the Canadian landing the last scheduled. Even this was delayed somewhat when assault craft arrived late due to weather delays. This caused additional difficulties since these delays allowed the tide to rise, covering many of the beach obstacles planted by the defenders. Yet enemy fire as the landing craft approached the beach was less than feared, largely because most of the German defenses were sited to fire across the beach, not out to sea.

The British Army had a unique organization in the 79th Armored Division, also known as “Hobart’s Funnies” after its commander, General Percy Hobart. This was a collection of specialized armored formations, and included DD (“swimming”) tanks, mine-clearing tanks, flame-throwing tanks, and several other specialized armored units that were attached to British and Canadian units as needed. The British had offered these to the American First Army, and General Omar N. Bradley, its commander, had agreed, but for reasons never explained, the Americans accepted only the DD tanks. On Juno Beach, these “funnies” would prove their worth.

The DD tanks were to be the first to land on Juno Beach, but once again, weather and tide caused some delays. With the rough seas, the naval group carrying the DD tanks with the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade decided not to launch them at the planned 7,000 yards from the beach, and instead launched them from much closer. Major J.S. Duncan, commanding B Squadron, 1st Hussars (6th Armored Regiment) agreed to launch at 4,000 yards from Juno Beach. Nineteen tanks launched, and 14 made it to the correct beach, landing about 15 minutes before the Regina Rifle Regiment. Major W.D. Brooks, commanding A Squadron, had more trouble. His landing craft approached to within 1,500 yards of the beach, but they were disorganized and out of position. One landing craft had its bow door chains shot away after one tank launched. Another landing craft unloaded directly on the beach. Ten other tanks were launched, but only seven reached the shore, where the Royal Winnipeg Rifles welcomed them. In the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade sector, all the tanks were carried ashore by their landing craft. Most of the tanks stopped on the beach, deflated their waterproofing, and then opened fire in support of their infantry.

Major Desmond Crofton’s Company C of the 1st Canadian Scottish Regiment had been attached to the Royal Winnipeg Rifles to extend their front. Landing on the extreme western end of Juno Beach, in Mike Sector, their immediate objective, a concrete casemate housing a 75mm gun, was found to have been knocked out by the bombardment. But the rest of the assault force had no such luck. Companies B and D, Royal Winnipeg Rifles were assigned the Courseulles strongpoint. They soon realized that the bombardment had not touched this position, leaving them no option but to storm the position in a frontal attack. Faced with machine guns and mortars, which opened fire while the Canadians were still 700 yards from the beach, many fell as they struggled to exit the landing craft. Joined by the tanks, the infantry soon cleared the opposition. Then they attacked across the Seulles bridge and cleared out the enemy on a little “island” between the river and the harbor. At the end of the battle, D Company had only one officer, Captain Philip E. Gower, and 26 men left standing. Landing with them in support, the 6th Company, Royal Canadian Engineers lost 26 men during the morning.

Companies A and C had meanwhile pushed inland against weak opposition until Company A came to the village of St. Croix-sur-Mer, where machine guns held up its advance. A call to the 1st Hussars (6th Armored) soon eliminated this opposition; despite mines and antitank guns, the battalion pushed ahead. By 5 PM, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles reached the village of Creully and consolidated a defensive position for the night.

Across the river, the other half of the Courseulles strongpoint was the responsibility of the Regina Rifle Regiment. In this sector, the tanks had arrived before the infantry as planned; they found that the bombardment in this area was as disappointing as across the river. But Lt. Col. F.M. Matheson’s battalion had been well trained for this objective, with each block of the village numbered and studied by the troops that would clear it. Landing shortly after 8 am, Company A ran into fierce opposition when it disembarked on Nan Green Beach directly in front of the strongpoint. The company commander, Major Duncan Grosch, had barely left his landing craft when he was shot in the knee. Men all around him were falling killed or wounded. His radioman was killed at his side. Unable to walk, Major Grosch saw the tide coming in and knew he would drown if he did not move. Struggling, he crawled toward the seawall, but the tide kept rising. Finally, two of his men grabbed him and pulled him to the dubious safety of the seawall.

The company’s second in command, Captain Ronald Shawcross, now took command. As he landed, the six men in front of him were cut down by enemy fire. He grabbed each man and pulled him back into the landing craft to save them from drowning, then ran ashore to join his company. He soon realized that only one mortar was firing and timed the fall of the shots. He sprinted forward in the interval between incoming mortar rounds, reaching the seawall with only four other survivors of his platoon. Now he tried repeatedly to attract the attention of the supporting tanks, which were firing randomly and unaware of Company A’s plight. They failed to respond, and the Reginas remained pinned down on the beach, kept from moving inland by enemy pillboxes shielded by a double apron of barbed wire and machine guns.

One of Company A’s platoon leaders, Lieutenant William Grayson, found a gap in the wire and maneuvered to the rear of a house where he found himself behind the enemy. But here too, he was blocked by barbed wire and a machine gun. But like Captain Shawcross, he soon realized that the machine gun was firing in some sort of time sequence. Once he figured out the schedule, Lieutenant Grayson raced forward, only to be caught in the barbed wire. As he waited for the machine gun to finish him off, nothing happened. Realizing that the gun crew must be changing ammunition belts or clearing a jammed gun, he tore himself free and raced to the concrete pillbox where he tossed a grenade inside, eliminating the opposition. The survivors fled, followed by Lieutenant Grayson. They led him to the next fortification, an 88mm gun that was also holding up the Canadians. He followed the fleeing Germans into the gun position armed only with his pistol and was greeted by 35 enemy soldiers with their hands raised.

With the machine-gun and antitank cannon out of operation, Captain Shawcross had his men jump the barbed wire and begin a deadly race through the extensive German trench system, clearing it before moving on to clear the town itself. Grayson had to later fight his way back to the beach to eliminate infiltrating Germans who had manned the abandoned machine-gun positions he had overrun earlier. For his gallantry, Lieutenant Grayson would receive the Military Cross. At the end of the day, Company A had only 28 men left of its original 120.

Although the Regina Rifle Regiment did not appreciate it at the time, the tanks of the 1st Hussars (6th Armored) had been busy on Nan Green as well. Sergeant Leo Gariépy landed and immediately fired several rounds into a pillbox. He then moved 50 yards inland and repeated his action, finally knocking it out. He then attacked a series of machine-gun positions that “were playing merry hell along the water line.” Other tanks knocked out a 50mm gun that was later found to have fired more than 200 rounds before being silenced. A nearby 88mm gun position suffered the same fate.

Even while the infantry and armor struggled to clear the beach, the Royal Canadian Engineers were trying to bridge an antitank ditch in front of Courseulles that prevented the tanks from getting into the town. Using their specialized armored vehicles, they worked under constant enemy fire. They also came under fire from German troops who, after Lieutenant Grayson had cleared the enemy trenches the first time, infiltrated back into them and resumed fire on the beach. Major J.V. Love’s Company D suffered the most from this fire: its commander was killed, and dozens of men were cut down as they exited the landing craft onto the beach. In fact, the company lost two landing craft to mined obstacles in the surf before even reaching shore. Lieutenant H.L. Jones reorganized the 49 survivors of D Company and moved to Courseulles, where they joined Company C, which had come ashore with little difficulty.

Even the brigade’s reserve, Lt. Col. F.N. Cabeldu’s 1st Battalion, Canadian Scottish Regiment found resistance still heavy when they came ashore. Mortar fire held them up for a while, and one company had to wait for an exit to be built before it could leave the beach. On the way to its objective, St. Croix-sur-Mer, it picked up its detached Company C and then pushed ahead against machine-gun and mortar fire. Passing through the Regina Rifles, the battalion continued advancing until the order came to halt for the night.

The Royal Marine Centaurs had little business on the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade’s beaches. Some were lost at sea, and others came ashore late. They answered calls for assistance, knocking out several enemy pillboxes and field positions during the day. Behind them, the plans for clearing beach obstacles and building beach exits were seriously delayed. The tide rose faster than anticipated and came up higher than expected. The Army engineers and naval beach parties were forced to wait out the rising tide before accomplishing their tasks.

On the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade’s beaches, Lt. Col. J.G. Spragge’s Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada landed on Nan White Beach. Company B landed directly in front of the Berniéres strongpoint and lost 65 men in the first few minutes ashore. Because of the delay in getting the tanks ashore, no armor support was immediately available. Lieutenant W.G. Herbert and two enlisted men attacked the most troublesome pillbox with grenades and Sten gun fire, knocking it out. As the battalion moved inland, it came under mortar fire that caused several casualties, in addition to those lost when mined obstacles exploded against their landing craft on the run to the beach.

The tanks of Lt. Col. R.E.A. Morton’s Fort Garry Horse (10th Armored Regiment) had been divided among the two assault battalions of the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade. The regiment’s B Squadron had been assigned to support the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, while C Squadron supported Lt. Col. D.B. Buell’s North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment. Although Colonel Morton would report that his tanks landed alongside the infantry, the infantry commander’s reports indicate that the infantry landed first, followed shortly by the supporting tank squadrons. Since the tanks were carried directly to the beach and not launched at sea, they all arrived safely, although one landing craft missed the beach and landed at a distance.

Company A of the Queen’s Own landed west of the strongpoint under mortar fire, but resistance was light, and the troops moved inland. The reserve companies, C and D, suffered somewhat from mines attached to obstacles on their way into the beach, but this did not impede their progress, and by the end of the day they had captured the battalion’s objective, Anguerny. On the beach, the 5th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers suffered casualties from two 50mm antitank guns within the Berniéres strongpoint before the infantry captured the guns.

Next in line along the beachfront, Lt. Col. Buell’s North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment found that the St. Aubin strongpoint “appeared not to have been touched” by the bombardment. Reducing that strongpoint fell to Company B, supported by Centaurs and Armored Vehicles, Royal Engineers (AVRE), who used their heavy mortars to clear the way. “The cooperation of infantry and tanks was excellent, and the strongpoint was gradually reduced,” states the official Canadian history. Enemy holdouts continued sniping at succeeding assault waves, however, until 6 that evening. Company A, landing alongside, suffered casualties from booby-trapped houses but otherwise made good progress off the beach. Reserve Companies C and D met only light opposition and were soon inland.

In the initial landing, Lieutenant M.M. Keith led his platoon of the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment ashore and rushed toward the seawall for protection from enemy fire. As they ran, three noncommissioned officers stepped on mines and were killed. Realizing the seawall was heavily mined and a deathtrap for his platoon, Lieutenant Keith veered toward a gap in the enemy barbed wire. Private Gordon Ellis shoved a Bangalore torpedo into the wire and ducked for cover. The resulting explosion also detonated a buried mine, and the force of the combined explosion killed Private Ellis and severely wounded Lieutenant Keith. Lance Corporal Gerry Cleveland, followed by the rest of Company A, dashed through the gap and began clearing the fortified houses beyond. Rifles, grenades, bayonets, and Bren guns were used to clear the enemy from St. Aubin.

Company B encountered a major concrete emplacement with a 50mm gun, machine guns, and 81mm mortars that commanded the beach. Steel doors barred entrance, and every conceivable approach was covered by fire. Using a series of tunnels, the Germans could easily move from position to position without exposing themselves to injury. Lieutenant Charles Richardson’s platoon was barely out of the surf before they encountered this monster. With only small arms and two small mortars, the platoon was ill equipped to tackle the Germans. Lieutenant Richardson decided to outflank the position and gain safety in the houses beyond the emplacement. Lieutenant Gerry Moran had led his platoon to the seawall but found that the massive enemy emplacement had a direct line of fire down the beach, the seawall exposed to its gunfire. Seeing Companies C and D about to land, he stood in the open shouting orders to his men to get off the beach. He lasted but a moment until a sniper shot him in the arm. As he was falling a mortar round exploded nearby, giving him further wounds. Tanks were needed, but none had yet landed in this area.

The Fort Garry (10th Armored) Horse’s C Squadron soon answered the call for help. The squadron had already lost four tanks—two drowned in the surf, another lost its crew to snipers, and the fourth was set afire by an antitank shell. Undaunted, squadron commander Major William Bray formed up his 16 remaining tanks along the beach while he waited for the engineers to clear a path through a minefield. But Major Bray’s patience soon lapsed, and he led his command into the minefield, losing three tanks to but bringing the rest into St. Aubin and providing much needed armor support to the struggling North Shore (New Brunswick) infantrymen. An AVRE “dustbin” tank carrying a short-barreled 12-inch demolition gun lobbed several of its 40-pound shaped charges at the concrete emplacement, while the North Shore (New Brunswick) Infantry flanked the position, shooting any German who showed himself.

The 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade’s reserve unit, Lt. Col. J.E.G.P. Mathieu’s Le Régiment de la Chaudiére, suffered casualties even before it reached the beach. As one company commander described it, “The LCAs of the 529th flotilla (HMCS Prince David) struck a very bad patch of obstacles and mortar fire on Nan White, and all foundered before touching down. The troops, however, discarded their equipment and swam for the shore. They still had their knives and were quite willing to fight with this weapon.” The battalion reorganized just beyond the village of Berniéres, where the French Canadians surprised the locals by speaking to them in French. Supported by Squadron A of the Fort Gary Horse (10th Armored Regiment), the battalion pushed inland, capturing some enemy gun positions as they moved.

On the beach, the Royal Marine Centaurs supported the 48th Royal Marine Commando as it cleared the village of Langrune-sur-Mer to the east of the beachhead. They also were assigned targets in St. Aubin. Here, as in the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade’s sector, the tide came in too fast and too high for the engineers to complete their work of clearing the beach obstacles and exits. The high seawall in front of Berniéres delayed clearing one of the exits until late in the day. Before dark, the four planned exits had been opened, although work on them continued. An AVRE placed a small box girder bridge over the seawall at Berniéres, enabling that exit to be used. Flail tanks, equipped with chains on a rolling bar in front, were used to clear routes through minefields.

While the assault brigades were clearing their respective beaches, Brigadier D.G. “Ben” Cunningham’s 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade circled offshore waiting for orders to land. These orders came at 10:50 am. Because of the untouched beach obstacles and cleared exits, it was decided to land the brigade over the Nan White beaches, behind the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade. Assault craft that had been waiting off Nan Red Beach and taking casualties from the St. Aubin strongpoint were diverted to Nan White. Initially, the brigade waited due to overcrowding on the beach, but shortly afterward the assault battalions landed, only to be delayed once more by overcrowding. Lieutenant Colonel C. Perch’s North Nova Scotia Highlanders could not get moving until after 4 that afternoon. They were supported by the Sherbrooke Fusiliers (27th Armored) Regiment under Lt. Col. M.B.K. Gordon. Lt. Col. G.H. Christiansen’s Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders followed, as did Lt. Col. F.M. Griffith’s Highland Light Infantry of Canada.

The leading landing craft commander thought things “looked pretty chaotic. It was apparent that the planned clearance of beach obstacles had not been carried out.” Carefully weaving his way through obstacles with unexploded mines on them and avoiding sunken and damaged landing craft, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders had been safely landed, even though several of the Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI) ships were severely damaged. Ninety landing craft, one in four, had been damaged or destroyed by mines, obstacles, or enemy gunfire. By the time the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade had finished unloading, the incoming tide had narrowed the actual beach to about 25 yards.

As the Highland Light Infantry struggled ashore carrying their bicycles and equipment, they found the beach “jammed [with] troops with bicycles, vehicles and tanks all trying to move towards the exits. Movement was frequently brought to a standstill when a vehicle up ahead became stuck. It was an awful shambles and not at all like the organized rehearsals we had had. More than one uttered a fervent prayer of thanksgiving that our air umbrella was so strong. One gun ranged on the beach would have done untold damage, but the 9th CIB landed without a shot fired on them.”

The 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade’s ultimate objective was Carpiquet Airfield outside Caen. The North Nova Scotia Regiment boarded the tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers (27th Armored) Regiment and set off for that objective. Their late start was compounded when they met resistance at Colomby-sur-Thaon, which further delayed the advance. Le Régiment de la Chaudiéres was also held up by direct fire from an 88mm antitank gun. The supporting artillery could not locate the gun, so it was left to the infantry to overcome the opposition. Lieutenant Walter Moisan led his Number 8 Platoon of Company A to attack. They got to within 200 yards of the gun when German machine guns held up the advance. Lieutenant Moisan led his men into a thicket that offered some concealment about 30 yards from the enemy gun. Accompanying a section led by Corporal Bruno Vennes, he advanced to take the gun with rifle fire when an enemy bullet ignited a white phosphorous grenade attached to his web belt. The lieutenant’s clothing was set aflame, and he suffered severe burns but refused medical treatment until the gun was secured. Corporal Vennes and his men raced into the enemy trenches and began a hand-to-hand fight, which ended when Corporal Vennes killed the gun crew with rifle fire. Lieutenant Moisan received the Military Cross and Corporal Vennes the Military Medal for the afternoon’s work.

By this time night was approaching, and it was too late to continue the advance. The Canadians settled into night defensive positions. On the beach, General Keller had come ashore with his advanced division headquarters and set up in a small orchard near Berniéres. The Canadians had achieved a lodgment with the landings at Juno Beach, although the battle to secure it would take several more days and require the defeat of several strong German armored counterattacks.

It is well known that the deadliest of the five invasion beaches on D-Day was Omaha, where the Americans suffered heavy casualties. But what is not so well known is that the next deadliest beach was Juno. Casualties sustained on the beach alone totaled 1,204 Canadian and British soldiers, and they increased as the troops moved inland. Of the five invasion beaches, the North Americans suffered on and secured the two most heavily defended on D-Day.

Nathan N. Prefer is the author of several books and articles on World War II. His latest book is titled Leyte 1944, The Soldier’s Battle. He received his Ph.D. in military history from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps Reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.