By William E. Welsh

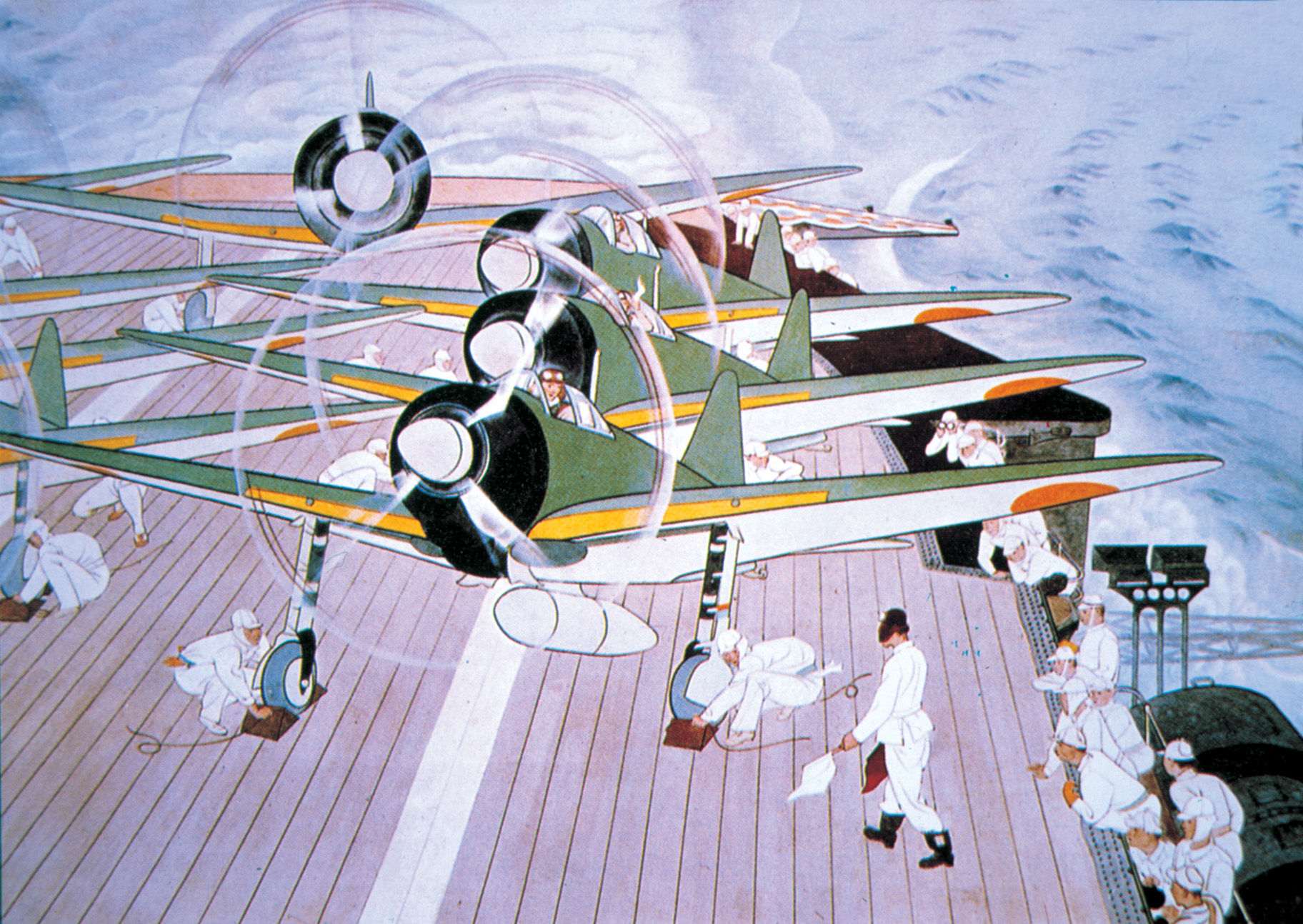

The advance of long ranks of scimitar-wielding Nubian and robed Bedouin archers on foot signaled a dramatic change in Ayyubid Muslim tactics against the Frankish army marching south along the Palestinian coast from Acre towards Jaffa. Behind the auxiliary foot soldiers came swarms of Muslim horse archers crowded together on the plain south of the Forrest of Arsuf.

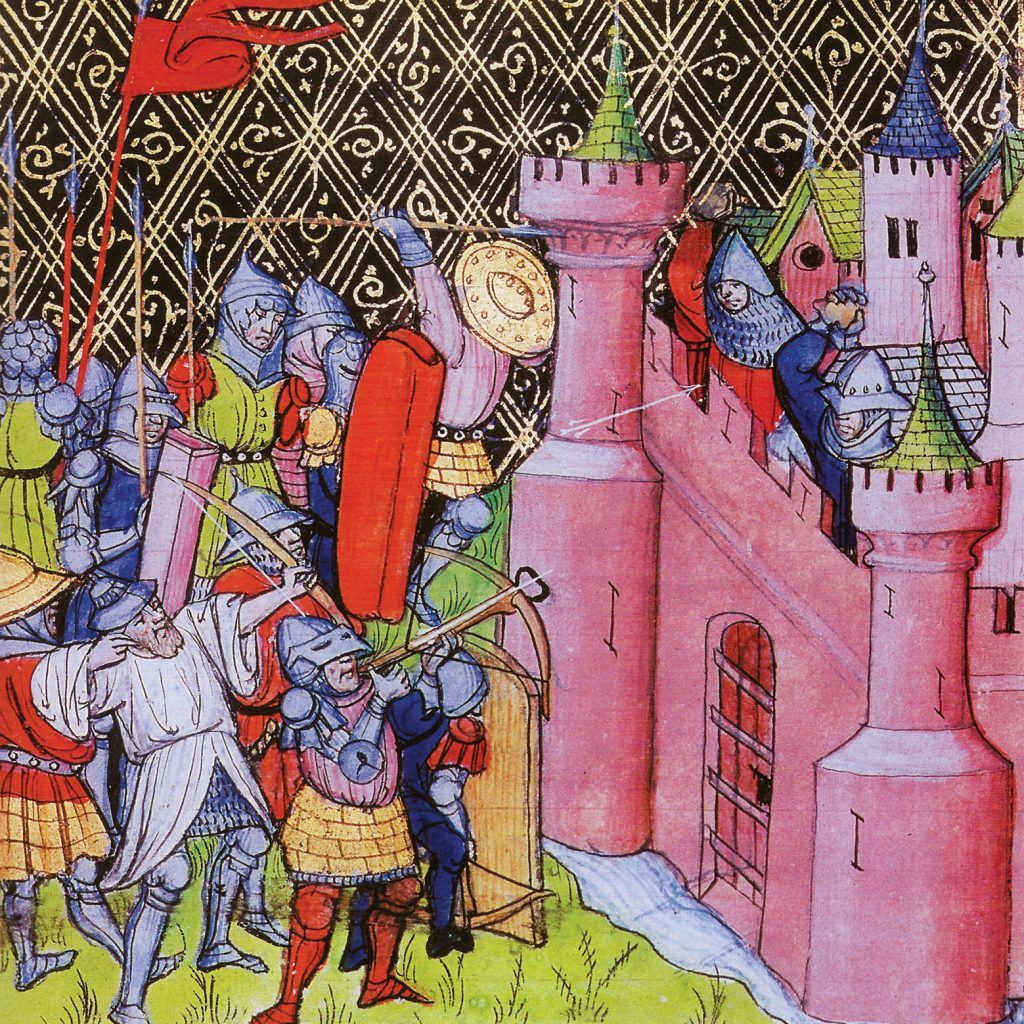

Frankish crossbowmen fired bolts as fast as they could into the advancing Muslim skirmishers, while the spearmen formed a protective wall in a valiant effort to hold the approaching hordes of Muslim warriors at bay. Behind the crusader infantry, mail-clad knights donned their helmets and took up their lances.

The bright summer sky soon darkened as clouds of arrows arced towards the Frankish troops who stood with their backs to the Mediterranean Sea. The epic clash that would pit the cream of Sultan Salah al Din (Saladin) Yusuf ibn Ayyub’s army against English King Richard I’s crusader army had just begun at mid-morning on September 7, 1191. Desperate to crush the Frankish host before it could secure the port of Jaffa for a drive on Muslim-held Jerusalem, Saladin had dispensed with the harassing tactics of the past two weeks in an attempt to destroy once and for all the multinational crusader army of the Third Crusade in a pitched battle.

Saladin was 49-years-old when he won a decisive victory over the Frankish army of the Kingdom of Jerusalem at the Horns of Hattin four years earlier on July 4, 1187. That day his Egyptian and Syrian troops had captured the Frankish commander-in-chief, King Guy of Jerusalem. This left the fate of the largest crusader state in the hands of Bailin of Ibelin, Lord of Nablus, one of the few high-ranking knights fortunate enough to have evaded capture that day.

In the aftermath of the disaster at Hattin, the three remaining Latin crusader states—the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli—were left with only a small number of warriors to defend them. If they were to remain in existence, these Latin states would need a rapid infusion of men and materiel from Western Europe.

Well aware that crusader reinforcements would soon be arriving, Saladin moved quickly to capture as many Christian-controlled cities, towns, and castles as possible in the Kingdom of Jerusalem while it was in a weakened condition. Within a week after his victory at Hattin, Saladin captured Acre, the kingdom’s largest port. He then compelled Bailin to surrender Jerusalem on October 2.

News traveled slowly in that age. Genoese merchants returning from the Levant brought news of the disaster at Hattin to Rome in early autumn 1189. Pope Urban III was heartbroken upon receiving the news of the disaster at Hattin. When he died on October 20, he was succeeded by Pope Gregory VIII. Gregory issued a papal bull on October 29 that established the Third Crusade. The purpose of the new crusade was to retake Jerusalem while rolling back other Muslim gains. Over the course of the next year, papal emissaries preached the crusade throughout Latin Christendom.

An influential Italian nobleman, Conrad of Montferrat, who had been residing in Constantinople with his Byzantine bride, arrived in the island-city of Tyre north of Acre just 10 days after the clash at Hattin. Conrad, who had sailed to the Holy Land on a personal pilgrimage, set to work immediately shoring up Tyre’s defenses to withstand an anticipated Muslim attack. Most importantly, he supervised the construction of a fortified trench across the causeway connecting the island to the mainland.

Saladin besieged Tyre, as expected, on November 12. The Muslims pounded the city’s walls with as many as 17 stone-throwing mangonels. Several efforts to carry the trench by storm failed. After a last-ditch failed assault against the trench on January 1, 1190, Saladin raised the siege and moved off.

While King Guy of Jerusalem remained in Muslim captivity in Damascus throughout the winter of 1187-1188, Conrad helped filled the leadership void. He sent letters to numerous Christian rulers in the West imploring them to send troops.

One of the first to respond to Conrad’s pleas was King William II of Sicily, who sent 50 ships and 200 knights to the Outremer in spring 1188. The Sicilian fleet played a crucial role in supplying the remaining Christian strongholds on the Levantine coast during Saladin’s continuing offensive.

Another one of the rulers to take the cross was 66-year-old Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I “Barbarosa.” A veteran commander, he departed Regensburg in May 1189 with 12,000 German troops. He planned to march overland to the Holy Land by the same route as the Christians of the First Crusade. One of his vassals, Duke Leopold of Austria, planned to follow by sea with another German army at a later date.

Tragedy struck the German crusaders on their trek through Anatolia. The emperor drowned in the swift waters of the Saleph River in the Taurus Mountains on June 10, 1190. Sources are conflicted as to whether he was trying to ford the river on his horse or merely swimming its cool waters as a respite from the broiling summer sun. Many of Frederick’s German troops turned back for home. Of those who continued east, many succumbed to disease in the last leg of their journey. The small number that survived joined Duke Leopold’s German army when it arrived in Acre the following year.

At the time the crusade was being preached, King Philip II of France and King Henry II of England, who was more than twice Philip’s age, were at war with each other. Henry’s so-called Angevin Empire included not only England, but also parts of western and northern France. Philip was desperate to annex some of Henry’s lands in France, particularly in Normandy.

As a result of ecclesiastical mediation, both Henry and Philip agreed to conduct a joint expedition to the Holy Land during the Third Crusade. When Henry died in July 1189, his son and successor, Richard I, agreed to eventually lead an English army to the Holy Land. The planning and preparations took a great deal of time because the two monarchs had to put their affairs in order before their departure. Philip and Richard wintered with their armies in Messina, Sicily, in 1190-1191. Some of their vassals led contingents to join the siege of Acre ahead of the arrival of the two monarchs.

Philip and Richard joined the siege of Acre with their large armies on May 20, 1191, and June 8, 1191, respectively. Over the course of the two-year siege at Acre, the crusaders investing the city fought nine major battles with the garrison and with Saladin’s relief army encamped nearby. The crusaders forced the surrender of the garrison on July 12, 1191.

Shortly after the capture of Acre, both Philip and Leopold returned home. The crusaders took 2,700 Muslim troops from the Acre garrison into captivity. Richard, who by then had become the commander-in-chief of the Frankish army at Acre, set harsh terms for the release of prisoners. He gave Saladin until August 20 to pay 20,000 gold dinars, release 1,500 Christian prisoners, and return the True Cross captured at Hattin.

Although Saladin was poised to pay half of the ransom by the deadline, as well as meet the other terms, Richard had no intention of extending the deadline. Since Richard planned to take nearly all of the crusaders south in a bid to retake Jerusalem, he could not risk leaving behind several thousand Muslim prisoners. The English king therefore decided to have the prisoners put to death when Saladin was unable to raise the rest of the money.

After retrieving the prisoners from Tyre where they were being detained, Richard ordered the massacre of the majority of the prisoners on August 20. Approximately 100 officers were spared in order to be ransomed at a future date. When Saladin’s troops tried to stop the butchery, they were driven back by the crusaders.

The crusaders enthusiastically slaughtered the Muslim prisoners for they believed it was suitable retaliation for the death of so many of their comrades during the two-year siege of the port city. “Thus was vengeance taken for the blows and crossbow bolts [during the siege],” wrote Norman chronicler Ambrose of Normandy, an eyewitness to the events of the Third Crusade.

Kurdish historian Baha ad-Din Shaddad, who would one day write Saladin’s biography, gave a sobering and graphic description of the massacre. “The crusaders brought out the Muslim prisoners bound in ropes,” he wrote. “Then as one man they charged them and with stabbings and blows with the sword slew them in cold blood.”

With no more impediments to his departure south towards Jerusalem, Richard prepared to evacuate Acre leaving behind a small force to hold it. Guy planned to accompany Richard on his march to capture Jerusalem. He did so in the capacity of a vassal and subordinate commander because a previous agreement ensured that Western monarchs had authority over the King of Jerusalem when campaigning in the Holy Land. Richard not only would have the assistance of Duke Hugh of Burgundy, who would lead the French forces in Philip’s absence, but also of the Hospitaller Master Garnier de Nablus and Templar Master Robert de Sable.

Richard immediately drew up plans to lead his veteran army south to secure ports in lower Palestine for a subsequent expedition to capture Jerusalem. The King of England carefully weighed the advantages and disadvantages of two different routes to Jerusalem. The inland route went from Acre to Nazareth to Jerusalem, while the coastal route when from Acre to Jaffa to Jerusalem.

Richard foresaw many drawbacks to the inland route. First and foremost, if the crusaders took the inland route, they would have to march through many valleys, which would give the Ayyubid Sultan Saladin’s army multiple opportunities to ambush it. Second, the supply line back to Acre would have been incredibly long and easy for Saladin’s Muslim army to interdict. Whichever route he took, his men would have to carry rations and water with them for there was a strong possibility that Saladin’s troops would scorch the earth and poison the wells to deny them food and water.

Richard did not make his decision quickly. While he might have been reckless and impatient in battle, he was focused, purposeful, and cautious when it came to assessing the strategic situation. In the end, he resolved that they would take the coastal route to Jaffa. Once he had secured the small anchorage at Jaffa, Richard also intended to capture the larger Muslim-held port of Ascalon 30 miles further south. With both ports in crusader hands, he hoped to be able to sustain his army during a siege of Jerusalem.

As for the dangerous march south through enemy territory, Richard knew that he must draw up meticulous orders regarding the provisional load each soldier must carry, the organization of his foot and mounted forces, and the length of the daily marches if he were to succeed in getting his army intact and with minimal losses to Jaffa.

His plan called for the crusader fleet to sail south alongside the army as it marched down the coast towards Jaffa. In late August sailors began loading biscuits, meat, wine, and water onto their ships for the expedition. The king instructed the ship captains to stay close to the shore so that smaller boats could ferry supplies to the soldiers when practicable.

Richard’s 1,200 knights and 10,000 foot soldiers set out from Acre on August 25, 1191. The fleet had sailed three days earlier to get into position. The coastal route would afford him an excellent opportunity to protect his mounted knights and his baggage train. The troops would march in three parallel columns while the crusader fleet followed closely along the shoreline to resupply the army at regular intervals on its 80-mile march.

Half of the infantry would march on the outside to shield the cavalry and supply train. The mounted knights would move in three divisions in the center. The other half of the infantry would march along the shoreline with the baggage train. One section would march on the outside fending off the Turkic horse archers who would undoubtedly harrass the column, while the other section of infantry marched with the baggage train. Richard planned to rotate the two groups of foot soldiers regularly to prevent exhaustion.

Since the army would be marching under the scorching summer sun, Richard planned to march in the morning and make camp at midday. He also planned to rest his army in camp on some days.

The Franks’ destination for the first day was Haifa. Richard gave strict orders to his subordinate commanders that under no circumstances were any of their knights to break ranks and charge the enemy. He told them that he was the only one who could authorize a charge.

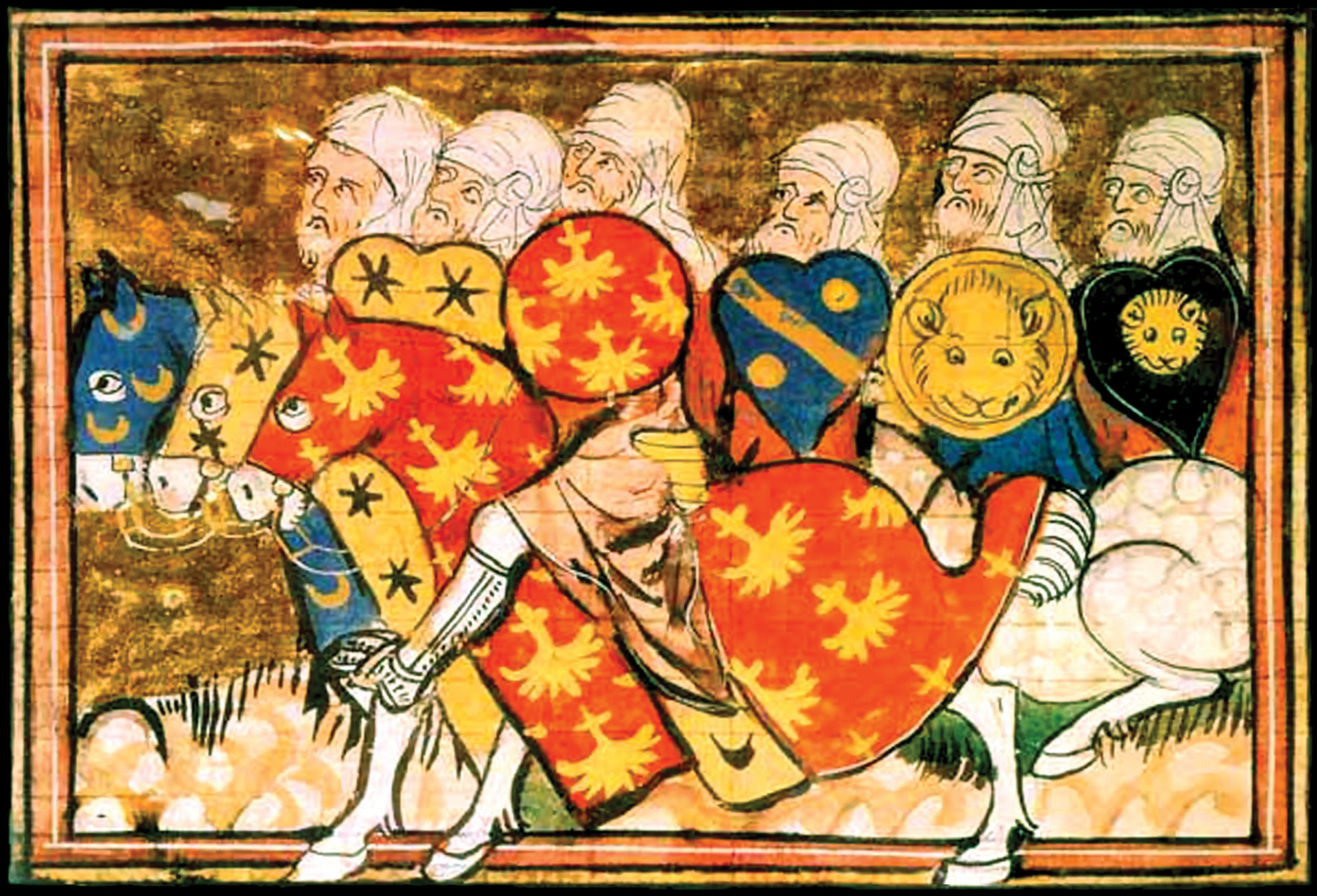

On the first day of the march, King Guy led the vanguard, Richard led the middle guard, and the Duke of Burgundy commanded the rearguard. Saladin’s horse archers wasted no time in harassing the rearguard. The Muslim horse archers were armed with a light shield and lance, a sword or club, and light bows. Their advantage lay in their speed and mobility. They swooped down to hurl javelins and fire arrows at the crusaders attacking in waves.

The crusader column soon became too extended and some of the Muslim light cavalry even reached the baggage train where they caused havoc. Realizing that a dangerous situation had developed, Richard and his retinue rode to assist the Duke of Burgundy. The English reinforcements helped the Duke of Burgundy and his French troops repulse the Muslims.

Realizing that he could ill afford to have the Muslims routinely disorder his rearguard, Richard decided that night that it would be better if the highly disciplined Templars and Hospitallers led the vanguard and rearguard, respectively, for the remainder of the march. As for the Duke of Burgundy, he naturally led the French contingents in the middle of the army.

Al-Adil Sayf ad-Din, one of Saladin’s brothers who the Franks called Safadin, directed the forces that would harrass the Christian rearguard. The harassing attacks were intended to provoke the knights in the rearguard into making piecemeal charges that would leave gaps in their ranks that could be exploited.

While Safadin directed the attacks against the crusader rearguard, Saladin shadowed the crusader army further inland with his main force and baggage train. If Safadin succeeded in separating the rearguard from the rest of the crusader army, Saladin planned to quickly reinforce him.

Each morning Safadin’s mounted archers congregated in the dunes from where they launched repeated assaults against the Frankish rearguard in an effort to separate it from the main body of the Frankish army. “You would have seen them coming like rain from the mountains, twenty here, thirty there,” wrote Ambroise.

As the march continued, the crusaders in the rearguard came under relentless pressure from the Muslims every day that they were on the march. The mounted archers showered them with arrows. Although the mail-clad knights did not suffer much, they soon began to lose a fair number of horses. Often the foot soldiers protecting the rear of the column had to march slowly backwards so that they could fend off the relentless Muslims troops.

Safadin decided on August 31 to launch a larger attack than he previously had. “The Muslims sent in volleys of arrows from all sides, deliberately trying to irritate the [Frankish] knights and force them to come out from behind the wall of infantry,” wrote Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad. “But it was all in vain. The knights kept their temper admirably and went on their way without the least hurry.”

The crusader infantry had only gambesons to protect them as they could not afford mail hauberks. These padded jackets were sufficient to stop the light Muslim arrows. On the days the rearguard was under attack, it was a common site to see Christian infantrymen with as many as a dozen arrows stuck harmlessly in their sturdy gambesons as they went about their duty of shielding the knights and baggage train from attack.

Unlike the light Turkic arrows, the bolts fired by the Frankish crossbowmen were deadly when fired at close range. In many instances, the crossbowmen were able to hold back the Turkic horse archers. But for those times when the foot soldiers were in dire need of assistance, Richard would allow small groups of knights to engage the Muslim cavalrymen. Yet the knights were under strict orders to promptly return to the safety of the column. Richard loved to fight, and he was often reckless in regard to his own personal safety. During one spirited skirmish with the enemy, a Muslim warrior stabbed Richard in the side with his spear, but the wound healed.

One of Saladin’s most renowned and fearsome warriors, Ayaz the Tall, was slain in another dust up on September 2. The spirited clash that day between the Muslims horsemen and the crusader infantry unfolded in low ground between two streams. Both sides incurred substantial casualties. The crusader spearmen who killed Ayaz brought back the slain warrior’s spear as a trophy.

Richard rested his army for two days beginning September 3. During that time, the crusader fleet resupplied his troops. While the Franks were resting, Saladin ordered his army to bivouac in the Forest of Arsuf while he spent the daylight hours reconnoitering the area for a suitable place to launch a full-scale attack against Richard’s army. Since his previous attempts to draw the crusader army into a pitched battle had failed, Saladin intended to force the issue when the crusader army set out again on its march.

The crusader army resumed its march on September 5, halting that day at Wadi al-Falik within a short march of the town of Arsuf. That night Richard ordered his troops to make camp between the sea and an expansive marsh that shielded it from attack.

Earlier that day Richard had sent a messenger to Safadin requesting a parlay. Saladin, who learned of the request, ordered his brother to prolong the talks as long as possible in order to buy time for Muslim reinforcements to arrive. But when Safadin met with Richard’s envoys on September 6 while the crusaders remained in their camp, he flew into a rage when they proved recalcitrant on certain points. In defiance of Saladin’s wishes, he broke off the talks before anything had been achieved.

That same day Saladin arrayed his army on the plain just south of the Forest of Arsuf. He had a total of 25,000 troops from Egypt, Syria, Jazira, and northern Iraq, as well as auxiliary Bedouin and Numidian foot soldiers. Saladin planned to send the foot soldiers forward first as skirmishers the following morning to engage the crusader column. They would be followed closely by a great multitude of horse archers. When a major fight was afoot, some of the horse archers preferred to move in close and dismount in order to fire with greater accuracy.

The Muslim left wing, which was commanded by Ala al-Din Ibn Izz-al Din of Mosul, consisted of units from Jazira and northern Iraq. The center was nominally commanded by Saladin’s eldest son, al-Malik al-Afdal Ali, and was made up of Syrian units. The de facto commander of the center was veteran general Sayf al-Din Yazkuj al-Qadi. The right wing, which was led Safadin, consisted of Egyptian units. Saladin’s reserve consisted of his elite Mamluk guard division led by Sarim al-Din Qaymaz al-Najmi, which was held in reserve. Saladin typically held back the Mamluks until the enemy’s formations were disrupted and its troops exhausted; at that point, the Mamluks went in to finish them off.

Richard expected a large-scale attack on September 7, and therefore carefully organized his column so that it could go into battle if necessary. The Templars held the vanguard, followed by the Bretons and Angevins in the second division, the Poitevins in the third division, the Anglo-Normans in the fourth division, and the Hospitallers in the rearguard. The Anglo-Normans were responsible for guarding the dragon standard that was mounted on a large cart so it could be seen from afar. “Their banner proceeded in their midst on wheels like a huge beacon,” wrote Muslim chronicler Baha al-Din.

Although the Franks expected that Saladin would engage them as they marched through the hilly terrain of the Forest of Arsuf, he allowed them to pass through unmolested. Once the army had emerged onto the plain of Arsuf, the sultan intended to launch an attack against the center and rear of the crusade army.

Richard’s army resumed its march at dawn on September 7. His scouts reported that Saladin’s army was arrayed for battle and likely to attack once the crusaders began to cross the plain. As if on cue, the Bedouins and Nubians advanced as skirmishers at mid-morning to begin the attack. Trumpets blared and kettle drums beat as the full weight of Saladin’s army surged across the plain. The crusaders braced themselves for the attack. Safadin’s Egyptian cavalry bore down on the Frankish rearguard from the north, while al-Afdal’s Syrian horsemen struck the rearguard from the east. The Hospitallers, and the infantry guarding them, soon found themselves under attack from two sides.

At the same time the Muslim center and right corps struck the Frankish rearguard, the northern squadrons of the left division assailed the crusader center in an effort to pin it down and prevent it from reinforcing the rearguard. Meanwhile, Saladin advanced his guard troops to a position behind al-Afdal’s corps. From that position, the heavily armored guard troops would be ready to exploit any gaps in the crusader line and engage Richard’s fearsome knights.

The foot soldiers shielding the crusader rearguard fought fiercely to hold back the Turkic mounted archers. Although the crossbowmen downed many of the enemy’s mounted archers, these casualties were quickly replaced by fresh troops so that the Frankish foot soldiers were not able to blunt the Muslim attack. A large number of Muslim horse archers decided to dismount in order to fire their arrows more accurately. As the fighting wore on, the Muslim archers succeeded in killing or maiming a significant number of the Hospitallers’ precious mounts.

The Christian foot soldiers soon grew weary from the unrelenting cavalry attacks. Their casualties began to pile up and gaps opened in their ranks. Meanwhile, the mounted Hospitallers behind them suffered through a steady rain of enemy arrows.

Saladin made his presence known to his troops, and because of this they fought with great ferocity and determination. The sultan, attended by two pages and with two spare mounts, rode back and forth along his line of battle exhorting his troops to slay the infidels. “The sultan was moving between the left and right wing, urging the men on to the jihad,” wrote Baha al-Din. “I met his brother in a similar state, while the arrows were flying past both of them.”

When some of Safadin’s Egyptian horse archers began to turn the left flank of the Frankish rearguard and gain the rear of Richard’s army, a group of crusader infantry raced to towards the shoreline in an effort to block them.

Hospitaller Grand Master de Nablus directed the defense of the rearguard. He sought out Richard twice to request permission to charge against the Muslim cavalry in an effort to eliminate it as a threat, but the English king refused him both times. Richard told him that when the moment was right, he would order all of the knights to charge at once. The King of England passed word to his division commanders that the signal for the charge would be six trumpet blasts.

Richard had no intention of allowing the Hospitallers to charge alone. He had to time the charge perfectly for maximum effect. He was waiting for the Muslim mounted archers to exhaust themselves before ordering a charge. If the Muslims scattered before the charge could strike home, the Frankish knights would lose their cohesion and their horses would be winded, thus leaving them vulnerable to destruction. But if timed just right, the Muslim cavalry would not be able to withstand a headlong charge by the heavily armored Frankish knights on their warhorses.

The weight of the crusader cavalry charge was such that no enemy could withstand it. They went into action with their lances gripped tightly under their right arms. When their lances shattered, they drew their broadswords and continued fighting on horseback.

As the battle wore on, De Nablus was having trouble holding his Hospitaller knights in check. Frustrated with the loss of some of their most valuable horses, they were eager to crush the enemy opposite them. Saladin’s mounted archers launched three major assaults against the rear of the crusader army.

During the last of these attacks, two mounted knights in the rearguard broke ranks to charge the enemy. One of these was Hospitaller Marshal William Borrel, and the other was one Richard’s household knights, Baldwin le Carron, who apparently had joined the rearguard to assist it. The exact reason they charged is not known. The two men may have mistaken Muslim trumpet blasts for those announcing Richard’s signal for a charge or they may simply have acted on their own.

Shouting the English battle cry, “St. George!” the pair thundered through the crusader infantry. Each bore down on a Muslim horseman and drove their lance into his body. Seeing the marshal ride out, De Nablus ordered the rest of his knights to join the charge. At the same time, some of the French knights nearby also charged. “Then the long-suffering Hospitallers advanced in order,” wrote Ambroise. “[The charge] took the Turks by surprise, for our men came down on them like lightning. All of the Muslims who had dismounted to fire their bows, which had hit our people hard, had their heads cut off.”

When Richard saw the Hospitallers ride forth, he ordered all of the other mounted squadrons in the center to join the attack, except for the Anglo-Norman troops. The Anglo-Normans had standing orders to remain in place guarding the dragon standard. The standard served as a rallying point for the entire army in the event of a crisis.

At the time of the first crusader charge, the crusader vanguard had reached the orchards on the northern outskirts of the town of Arsuf. The Templars, who were far from the fighting, stood by until such time as they received further orders. As for Richard, he and his household troops enthusiastically joined the charge.

To the Muslims it seemed as if the crusaders had made a well-coordinated charge. “I saw them grouped together in the middle of the foot soldiers,” wrote Baha al-Din. “They took their lances and gave a shout as one man. The infantry opened gaps for them and they charged in unison along their whole line.”

Seeing the Franks charge, Saladin committed his Mamluk heavy cavalry in an effort to keep the crusaders from destroying his army. Only the Mamluks could engage the knights on anything close to equal terms. In the interim, the charging Frankish knights overran the Muslim foot soldiers and slammed at full force into squadrons of light cavalry that were unable to withdraw in time to avoid contact.

As the Frankish knights drew close to the forested hills beyond the plain, Richard ordered them to halt for fear that if they attempted to fight their way into the hills and ravines that lay beyond. The king anticipated that they might be ambushed in the broken terrain.

After sending forward his Mamluk reserve, Saladin gathered his staff, standard bearers, kettle drummers, and a small contingent of bodyguards and led them to a prominent hill near the edge of the forest where they deployed. The beating of the kettle drums was a signal to rally on his position. The Frankish knights reformed once behind their infantry and charged forth anew to clear the plain of the Muslims and ensure that their foe was beaten.

The Muslims “were so thoroughly repulsed, so that for two full leagues around you could see only fugitives of those who before were so cocksure,” wrote Ambroise. With the crusader heavy cavalry charges having broken the Muslim formations the entire length of Saladin’s battle line, all of his troops fell back to the relative safety of the Forest of Arsuf. Although his army was on the verge of rout, Saladin by his presence was able to reform them and stave off what might have been a disaster. Taking a cautious approach to the situation, he issued orders for those still mounted to lead their horses to water from nearby streams and also directed the extraction of the wounded for medical care.

This left Richard and his exhausted soldiers to march unhindered into Arsuf. Jaffa lay only 15 miles beyond Arsuf, and Richard’s troops arrived at their destination on September 9. In a campaign that culminated in the clash at Arsuf, Richard had shown that the crusaders could defeat Saladin’s army in a pitched battle. Because Saladin’s army remained intact, Richard had achieved only a marginal victory. Frankish cavalry losses were minimal, but the Frankish foot soldiers suffered 700 casualties. The Muslims were believed to have lost 7,000 men, although their losses might have been substantially less.

Although Richard had achieved a tactical victory at Arsuf, he did not gain much from a strategic standpoint given that his ultimate goal was the capture of Jerusalem. That goal would elude him over the course of the next year. Twice he advanced his armies towards Jerusalem during that time, only to withdraw because he knew he lacked the resources to capture the heavily fortified, well-defended city in what likely would have been a siege comparable to the one fought at Acre. Although they failed to retake Jerusalem, the senior leaders of the Third Crusade, among which Richard the Lionheart was undoubtedly the most distinguished, had succeeded in reversing most of Saladin’s conquests after the Battle of Hattin.

After protracted negotiations with Saladin, as well as a great deal of time spent mediating disputes among the senior leadership of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Richard departed for home on October 9, 1192. His return journey was a long odyssey. When the galley in which he was sailing shipwrecked on the Dalmatian coast, Richard and a handful of companions set out disguised as pilgrims returning from the Holy Land to travel home on foot through Austria and southern Germany.

In a cruel twist of fate, Richard was captured and imprisoned first by his former rival Duke Leopold of Austria, who bore a grudge against Richard from the siege of Acre, and then by Leopold’s sovereign lord, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI. Held for a large ransom, he finally made it back to England in March 1194. He received a tumultuous welcome, as befitted a hero of the crusades.