By Joshua Shepherd

In the early afternoon of December 5, 1757, the men of Prussia’s 26th Infantry Regiment were drawn up in assault formation just south of the Silesian village of Leuthen. Snow blanketed the ground, but the skies had cleared to reveal brilliant sunlight. Despite the cold, the men in the ranks, among the best disciplined troops in Europe, remained motionless. The ranks of the 26th Infantry consisted of seasoned veterans who were under no illusions about the grim nature of their assignment. Within minutes, they were scheduled to spearhead an assault against a numerically superior Austrian army.

Without warning, a commander abruptly trotted along their front rank, only to draw rein in front of the regimental standard. Stooped in the saddle and wearing a plain blue coat, he made a distinctly unimpressive appearance. To the soldiers in the ranks, his arrival was nonetheless a heartening sight. It was none other than Frederick II of Prussia, the ascetic warrior-king known affectionately to his men as “Old Fritz.”

True to form, the monarch issued brief and straightforward orders. “You must march against the abatis, but do not advance so quickly that the army cannot keep up with you,” he said. Promising to follow closely on their heels with the entire army, Frederick exhorted the men to “go for them with the bayonet and run them out.” Yet in the coming struggle there could be no turning back for the Prussians. “It’s a case of do or die,” said the king. “You’ve got the enemy in front, and all our army behind. There is no space to retreat and the only way forward is to beat the enemy.”

The desperate battle that unfolded on the fields of Leuthen stemmed from a long-standing dispute over the province of Silesia, as well as the Prussian monarch’s unbounded ambition. Assuming the Prussian throne in May 1740, the young king quickly demonstrated that he was determined to confront the oldest dynasties of Continental Europe.

Within months of his ascension, Frederick conceived the unthinkable, launching an invasion of the Austrian province of Silesia. In a whirlwind campaign that took the courts of Europe by surprise, the upstart Prussian king annexed Silesia in December 1740. Frederick owed his victory in 1742 in the First Silesian War, which secured almost all of Silesia for Prussia, to his superb generals and his well-trained troops. When he became aware of a secret coalition involving Austria, England, and Saxony against him to deprive him of Silesia and his inheritance, Frederick invaded Bohemia, sparking the Second Silesian War in 1744. The Treaty of Dresden the following year confirmed his possession of Silesia. But his naked aggression in Silesia ensured nearly perpetual war with Austria’s Hapsburg dynasty during his reign.

Frederick the Great, as he eventually would be known for his military acumen, was a skilled musician, poet, and patron of the arts; he preferred to converse in French rather than German. In an age of oft-brutal absolutism, Frederick was regarded as an enlightened monarch who hoped to elevate the status of the Prussian state, which had long been considered a backwater kingdom of northern Europe.

Despite his predilection for enlightened pursuits, Frederick also was a thoroughgoing soldier. He stretched the means of the state to recruit, train, and equip a modern army that became capable of confronting in battle the major powers of Europe. A proponent of rigid discipline, he continued the military reforms that had been begun by his father and endeavored to foster native production of war materiel. By the 1750s, Frederick had increased his army to 154,000 troops, but his perfidious conduct with the Allies put his kingdom in increasing danger.

His expansionist policies were bound to elicit the resentment of rival monarchies. In 1756, Prussia faced a diplomatic and military crisis of the first order. Frederick found himself allied to Great Britain but facing a hostile coalition of continental powers that included Austria, France, Russia, Sweden, Saxony, and Bavaria. Despite the mounting power of the Prussian military machine, such an overwhelming alliance bent on bringing Frederick to heel threatened the very existence of an independent Prussia.

Matters only worsened in 1757 as the Third Silesian War, a regional theater of the larger Seven Years’ War, heated up following Frederick’s invasion of Saxony in 1756. Frederick suffered an embarrassing and costly defeat at Kolin on June 18 of that year in Bohemia at the hands of the Austrians. The French routed an English-Hanoverian army at Hastenbeck on July 26. Then, a Prussian army attacked a Russian invasion force in East Prussia, only to be defeated at the Battle of Gross-Jagersdorf on August 30. In the wake of their success at Kolin, the victorious Austrians countered Prussian aggression by invading Silesia.

Facing reversals on nearly every front, Frederick gambled big. Mustering all available troops that could be reasonably spared, the king marched west to face the combined forces of France and the Reichsarmee, the erstwhile forces of the Holy Roman Empire. After weeks of jockeying for position, the two sides clashed near Rossbach in Saxony on November 5. With just 22,000 men, Frederick was badly outnumbered by 42,000 French and Imperial troops. In a shocking afternoon of hard fighting, Frederick smashed his opponents. At the cost of only 169 men killed, the Prussian army inflicted casualties totaling 3,000 killed and 5,000 captured on the Franco-Austrian army.

Rather than resting on his laurels, though, Frederick turned his attention eastward, where a powerful and determined Austrian nemesis still threatened the Prussian kingdom’s heartland. The destruction of the French menace at Rossbach “merely set me free to seek new dangers in Silesia,” Frederick later said. The Prussian king struck camp on November 13 and put his army in motion.

But he was already too late to stem the tide of mounting disaster. Fully exploiting the weakened state of Prussian defenses in Silesia, the invading Austrians overran half of the wealthy province. The skeleton Prussian field army in Silesia, under the command of August Wilhelm, Duke of Bevern, was badly outmatched. The provincial capital of Breslau surrendered to the Austrians on November 25. The Austrians captured Bevern shortly thereafter during a personal reconnaissance.

Intent on a final humiliation of the nettlesome Prussian monarch, the Austrians had assembled a formidable army. With 66,000 men, the Austrians would easily double the size of any army the Prussians could field at the time. Overall command of the Austrian army, though, went to Field Marshal Prince Charles of Lorraine. Brother-in-law to Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, Prince Charles possessed a less-than-stellar record as a field commander and owed his appointment to army command to political considerations rather than military merit.

The Austrian second-in-command, Field Marshal Leopold Graf Daun, was of far different makings. Daun was an experienced field commander of lengthy service and regarded as an officer who remained cool under pressure. Daun had been in command of the Austrian army at the Battle of Kolin and had already proved that he could, under the right circumstances, best the Prussian monarch on the battlefield.

When Frederick reinforced the remnants of Bevern’s army on December 2, he was at the head of a moderately sized army of 38,000 men. Two-thirds of Frederick’s army was composed of Bevern’s former troops, who were badly demoralized after a string of embarrassing drubbings at the hands of the Austrians. The other one-third consisted of veterans of Rossbach, a core of seasoned troops with soaring morale after their shattering victory over the French. Their contagious enthusiasm, paired with the personal presence of the king himself, was just the tonic that the army needed.

Frederick opted for an uncharacteristically genial approach to discipline in the hopes that a softer hand would engender much-needed esprit-de-corps in his field army. The Prussian king increased rations of food and alcohol, then spent time personally circulating through the army’s camps, cementing a vital rapport with the common soldiers who would wage the coming fight. For an austere monarch widely regarded as an aloof commander, the sudden reversal of leadership technique seems to have worked. As Frederick readied for a major clash with the Austrians, he led a well-fed and enthusiastic army.

Having prepared his enlisted ranks as best he could, Frederick turned his attention to his officer corps on December 3. That evening, the king invited the army’s regimental and battalion commanders to his headquarters. The gathering was a spectacle of 18th-century military finery: infantry officers in cocked hats and laced uniforms, dragoons in gleaming breastplates, and hussar officers garbed in elaborately trimmed jackets.

When Frederick joined them, his appearance was a study in anachronism. The old warrior was dressed in a plain and dirty blue uniform, and Frederick was obviously exhausted from incessant campaigning. Deviating from his accustomed French, the king addressed his officers in German. He announced his intentions to attack the numerically superior Austrian army near Breslau. He said the risk involved with being outnumbered was unavoidable.

“I fully recognize the dangers attached to this enterprise, but in my present situation I must conquer or die,” he told them. “If we go under, all is lost. Bear in mind … that we shall be fighting for our glory, the preservation of our homes, and for our wives and children.” As his voice grew weak, Frederick made a final appeal to honor.

During the frigid pre-dawn hours of December 4, the Prussians broke camp and were on the move by 4:00 am Marching toward the presumed location of the enemy entrenchments outside of Breslau, the Prussians advanced in four columns. Out in front was a screening detachment of hussars, personally accompanied by the king. It did not take long for the Prussians to enjoy a bit of good luck. When the cavalrymen approached the village of Neumarkt, locals revealed that the town was still garrisoned by 1,000 Croats who were guarding the Austrian army’s field bakery.

Frederick quickly pounced at the opportunity. Sending a mounted detachment to the heights beyond the town in order to cut off the enemy’s retreat, Frederick unleashed his hussars against Neumarkt. The cavalrymen battered in the town’s gates, then quickly routed the disorganized garrison.

As the Croats scattered beyond town, they were easily run down or captured by Prussian horsemen. The morning’s developments proved an unexpected boon to the Prussians. The field bakery, including precious stockpiles of flour, had been captured intact. Neumarkt’s hapless Croat garrison had suffered badly: 120 were dead on the field, another 569 taken prisoner.

Frederick gathered a vital bit of intelligence. On the heights beyond the town, the Prussians had discovered an enemy engineering detachment clearly engaged in laying out a new position. It was now apparent that the Austrians, rather than staying put in the relatively secure entrenchments outside of Breslau, had come out in the open for a fight.

Frederick was only too pleased to oblige. After setting up his headquarters for the night in Neumarkt, the king sent out mounted detachments to locate the enemy’s whereabouts. His cavalry returned with promising news. The Austrians were in the open. Although their lines stretched for five miles and straddled several villages, they had not taken pains to construct any substantial field fortifications. Without a second thought, Frederick ordered preparations for a general advance early the next morning.

The Prussians were on the move at 5:00 am in two columns of infantry and heavy flanking columns of cavalry. Frederick, as was his usual custom, rode with the advance guard, which included a mixed bag of irregulars, riflemen, and hussars. The day dawned clear but exceedingly cold. A light snow covered the ground, which had frozen solid overnight. The hard ground facilitated the army’s march, but the low temperatures occasioned grumbling in the ranks. When one soldier complained of the cold conditions, the king told him that it would be hot soon enough given that a major fight was in the offing.

As the Prussians groped their way forward, they discovered an Austrian forward post at the village of Borne. The forward position was held by an unusually large detachment consisting of three full regiments of veteran Saxon infantry, two regiments of Austrian hussars, and a contingent of Croat irregulars. Friedrich Moritz, Graf von Nostitz-Rieneck, who commanded the detachment, was caught unprepared by the sudden appearance of the Prussians.

Unfortunately for Nostitz, the weather seems to have worked against him. A dense fog shrouded the landscape that morning, concealing the full extent of the approaching Prussian forces. By the time Nostitz realized he was facing a substantial enemy force, it was too late.

Nostitz ordered his men to make an orderly withdrawal, but Prussian mounted units were simply moving too fast. Although the bulk of the Austrian cavalry escaped the field, the Saxon infantry was less fortunate. Prussian hussars swarmed to the rear of Borne, cutting off the escape routes from the village. Hundreds of panicked Saxons were snapped up as prisoners of war, while the remnants of their regiments trudged back to the safety of Austrian lines.

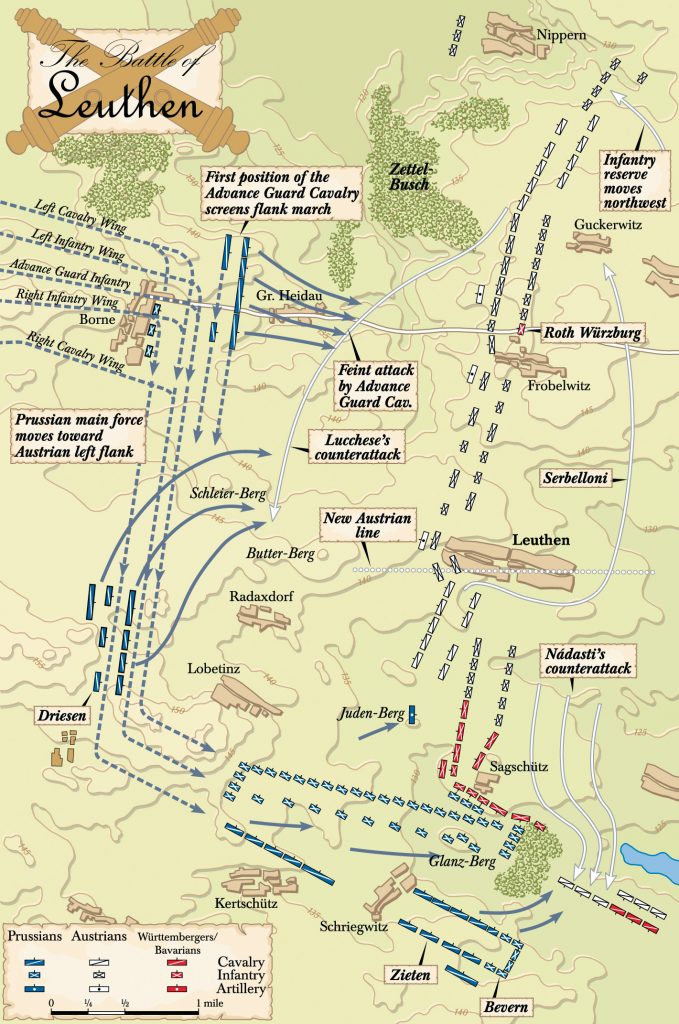

As soon as Borne was cleared of the enemy, Frederick mounted the heights east of the village for a better look at the Austrian position farther east. Prince Charles and Daun had chosen their ground reasonably well, taking advantage as best they could of rising ground and small villages that flanked the primary thoroughfare to Breslau. From the village of Nippern on the right to Sagschutz on the left, the Austrian line stretched for five miles.

In an effort to make their flanks less accessible to a Prussian turning movement, the Austrian commanders had placed their men in three ranks, rather than the customary four ranks. Although such a move did indeed seem to place the Austrian flanks beyond Prussian reach, it left the Austrian lines longer and thinner than normal. In the event that troops would have to be reshuffled to reinforce threatened sectors, the Austrians would be at a decided disadvantage. Moreover, the Austrian left fell far short of boggy ground that could have anchored that flank. South of the Austrian position, there was sufficient room for the maneuver of infantry.

From his vantage point on the high ground east of Borne, Frederick sized up his enemy’s dispositions. Indeed, the Prussians were quite familiar with the ground, having conducted maneuvers in the area the previous autumn. The king quickly realized a potential weakness in the Austrian position. To the east and south of Borne, the ground consisted of decidedly rolling terrain that could mask Prussian troop movements. True to form, Frederick opted for a grand turning movement against the Austrian left.

To distract the Austrian commanders, Frederick developed an audacious feint against his enemy’s right. Prussian cavalry deployed east of Borne, seemingly in preparation for a direct attack on the Austrian lines. On the Prussian left, Frederick ordered a series of pointless but noisy marches and countermarches, then deployed decoy units of his infantry in full view of the enemy.

The flurry of harmless activity nonetheless worked miracles. The commander of the cavalry on the Austrian right, Lt. Gen. Count Joseph Lucchesi d’Averna, became convinced that the full weight of the Prussian army was about to fall on him. He dispatched a desperate plea for reinforcements to Prince Charles and Daun. Both officers were observing the field from the vantage point of a windmill just north of the village of Leuthen in the Austrian center.

Although they initially demurred at Lucchesi’s request, they soon became convinced that Frederick intended to turn their right. They issued orders at midday for the army’s reserves under the command of Lt. Gen. Leopold d’Arenberg to reinforce the right wing.

In short order, d’Arenberg had his reserves, including eight battalions of crack German, Dutch-Walloon, and Hungarian troops, positioned to support the Austrian right. For his part, Daun eventually left the windmill in the army’s center in order to personally supervise defenses farther north. Prince Charles, who was increasingly convinced that the action would unfold on the right, stripped even more troops from his left by transferring that wing’s cavalry, under the command of Lt. Gen. Johann Baptist Graf Serbelloni, to the right wing.

Unfortunately for the Austrians, they had completely misread the Prussian king’s intentions. While Prince Charles prepared for an epic fight on his right, Frederick was making preparations to smash his left. Using the rolling terrain south of Borne to his advantage, Old Fritz marched his men south and east in a massive turning movement that would place the bulk of his army off the exposed Austrian left flank.

Although much of the flank march would be hidden from view, the Austrians nonetheless became aware that Frederick’s army was quitting its position in the vicinity of Borne. Under the firm belief that Frederick had initially intended to strike his right, Prince Charles simply could not entertain the notion that Frederick was seeking a fight elsewhere. Confident in his army’s superior numbers, Charles was delighted to discover that the Prussians were marching off to the south. Convincing himself that Frederick had been intimidated into quitting the field, Charles brushed off the Prussian movement. “Our friends are leaving, let them go in peace,” he said.

For the Austrian army, such misplaced confidence was a recipe for disaster. From his vantage point on the Austrian left, Lt. Gen. Franz Leopold Graf Nadasdy grew increasingly alarmed by the Prussian movements. With a better view of the field than his commanders, Nadasdy realized that, far from retiring from the field, the Prussians were preparing to attack his position. Nadasdy dispatched repeated requests for reinforcements, warning of an impending attack. Prince Charles, apparently considering Nadasdy’s warnings as little more than the unlikely fears of a hysterical subordinate, failed to act. In any event, the Austrian reserves had already been sent farther north.

The Prussians began arriving at midday at their assigned positions opposite the Austrian left. By making his approach march in two columns, Frederick would simply have to turn his troops left before launching his attack. Far on the Prussian right were six battalions of infantry, intended as flank security. To their left were 53 squadrons of cavalry under the command of an aggressive commander of horsemen, Lt. Gen. Hans Joachim von Zieten. The main body of Frederick’s infantry formed in two lines at an oblique angle to the Austrian flank. Additional cavalry was positioned on the left flank, with other horsemen positioned behind the army’s center as a general reserve.

The veteran Prussian infantry, under the command of Lt. Gen. Prince Moritz of Anhalt-Dessau, would provide the main thrust of the attack. Frederick’s front line consisted of a densely packed twenty battalions intended to provide a smashing blow against the Austrian flank. The second line was made up of a supporting eleven battalions who would exploit any potential breakthroughs. The attack would unfold en echelon from right to left. It would begin on the right with each battalion stepping off 50 paces ahead of its neighboring battalion to its left. The en echelon tactic ensured that as the attack developed it would gather increasing momentum against a weakened enemy.

In front of his main body, Frederick had placed the troops who would spearhead the assault. This force, commanded by Maj. Gen. Karl Heinrich von Wedel, consisted of some of the best troops in the Prussian army. Three battalions, two from the 26th Infantry and one from the 13th Infantry, were positioned ahead of the right front of the Prussian main line. The 26th Infantry was a Pomeranian outfit containing a good number of Slavic-speaking Wends with a reputation as fierce fighters. The 13th Infantry, recruited from Berlin, was a rigidly disciplined unit that had earned the nickname “Thunder and Lightning Regiment.”

Despite the Prussian predilection for wielding the bayonet, Wedel’s lead troops, who received 60 rounds of ammunition per man, were expected to deliver heavy fire as they advanced. As the troops readied themselves, Frederick rode to the front of Wedel’s three assault battalions to offer final instructions and a few words of encouragement. It was obvious that the lead troops would suffer heavy casualties. The pleasantries were interrupted by Prince Moritz, who was anxious to get moving. Moritz said that the winter sun would set quickly and that only a few hours of daylight remained to defeat the Austrian army.

Frederick gave the order to advance at 1:00 pm. Wedel’s three battalions, in the well-dressed lines that were the hallmark of the Prussian infantry, angled toward the Austrian left. Their initial objective was a slight hill, known as the Kiefernberg, which was situated near the village of Sagschutz. In front of the hill was a drainage ditch that would impede the Prussian assault.

Awaiting the Prussian onslaught, General Nadasdy had grown increasingly frustrated by the lack of support from the Austrian high command. The fiery Hungarian nobleman was widely regarded as the best cavalry commander in the Austrian service, and he did the best he could to prepare for a toe-to-toe infantry fight.

Unfortunately, the troops at his immediate disposal, the army’s Reichstruppen, were considered below par. The Reichstruppen, imperial regiments raised from smaller German states allied to Austria, had far less interest in fighting the Prussians than the native Austrian regiments. The troops positioned astride the Kiefernberg, 13 battalions of Wurttembergers, were supported on their right by 10 battalions of Bavarians.

As Wedel’s vanguard marched forward in crisp ranks, Austrian guns opened up with solid shot, tearing gaps in the Prussian line. True to form, Frederick’s tightly disciplined veterans closed ranks and pressed forward. Closing to musket range, the Prussians were greeted with a hail of musketry but kept moving, pausing only to unleash volleys of their own.

The inexperienced Wurttembergers traded a few volleys, but in the face of the determined assault, they began to drift away from the field. Sensing an opportunity, Wedel’s troops pressed through the gap. With Prussians pouring through the hole left by the retreating Wurttembergers, the Bavarian battalions on their right were forced to give way. In just 15 minutes of sharp fighting, the Austrian left collapsed.

Wedel, whose blood was up after overrunning the enemy so quickly, pushed his three battalions north in an attempt to maintain pressure on the enemy. Confused Austrian and Hungarian troops, caught up in the pell-mell retreat, fled north until reaching better ground. Rallying across the rising hill of the Kirchberg, the Austrians reformed to stem the tide of the Prussian advance.

The momentum of the Prussian attack, paired with robust artillery support, was proving unstoppable. The initial Prussian assault had gone remarkably well. It proved so successful that Frederick was forced to order Wedel to slow down in order to allow the main body to catch up. The king also ordered up artillery support to keep pace with the infantry. The Brummers, Prussian 12-pounders, were brought up to high ground from which they could bombard the new Austrian position atop the Kirchberg. With a storm of iron falling on their position and Prussian infantry lashing around their flanks, the Austrians were forced to retreat north for the next possible defensive position, the village of Leuthen.

Despite the stunning success of the initial Prussian breakthrough, Wedel’s three battalions had suffered heavy casualties during their attack. The heavy musketry also had depleted cartridge boxes, and some of the men were running out of ammunition. Eager to get the main body into action, Prince Moritz arrived at the front and encouraged Wedel’s men to fall back and make room for fresh troops. “Boys, you’ve won honor enough,” he shouted to Wedel’s troops. “Fall back to the second line!” Wedel’s exhausted shock troops, disinclined to give up the field, simply ignored the order and shouted for more ammunition.

Nadasdy was far from resigned to defeat. He had hoped to use the Austrian cavalry for a strike against the flank of the advancing Prussians. The Austrians, reinforced by Nostitz’ Saxon cavalry, swung around the Prussian right, but were badly hampered by the terrain east of Sagschutz. The ground was broken with a number of woodlots and thickets, which rendered large-scale cavalry maneuvers difficult.

A stern Prussian defense made matters worse. As the Austrians charged forward, they were greeted by a sheet of musketry from six Prussian infantry battalions which had been posted on the far right as flank security. The Prussian cavalry, under the command of Lt. Gen. Hans Joachim von Zieten, mounted a countercharge, and a swirling, confused cavalry fight developed. Wildly swinging his saber, Nostitz was in the thick of it and sustained 14 wounds. Left reeling in the saddle, the Austrian general was finally overpowered and captured by Prussian horsemen.

A brutal back-and-forth fight unfolded as each side temporarily gained the upper hand. At one point, Nadasdy’s hard-charging hussars worked their way around the Prussian flank and pitched into the rear of the Prussian 2nd and 11th Dragoons. Initially meeting with success, the hussars were driven off after a countercharge mounted by the 1st and 4th Prussian Dragoons secured the flank.

The Prussians finally gained the upper hand when the Cuirassier Brigade under the command of Maj. Gen. Robert von Lentulus charged across the field, clearing the ground of the exhausted Austrian cavalry and snapping up fifteen enemy artillery pieces. Austrian horsemen fled the field, leaving the ground open for Prussian cavalry to operate with impunity. Frederick’s horsemen fell on the rear of the demoralized Wurttemberg infantry, which was still in full retreat for the north. Unable to escape the deadly trap, 2,000 of them were captured.

With his left flank shattered, Prince Charles finally realized that the main Prussian thrust was coming from the south, not the north, and frantically scrambled to reform his entire army to confront the threat. Shuffling reinforcements to the left would be a difficult process, and the prince desperately needed to buy time. For the salvation of his entire army, he turned to the reserve cavalry.

He was nearly left in the lurch. Rather than risk his cavalry against massed Prussian infantry, Serbelloni pulled his command to relative safety behind Leuthen. But sensing the impending peril to the Austrian army, Brig. Gen. Adolf Nikolas, Baron Buccow, threw his men into the fight. Charging forward with a scratch force of cuirassiers, dragoons, and carabineers, Buccow succeeded in slowing down the Prussian steamroller. But with his command badly chewed up in the face of overwhelming infantry and artillery fire, Buccow was forced to quit the field. The high cost in casualties bought precious time for the Austrians.

Mass confusion reigned as the Austrian regiments arrived piecemeal at the hastily formed new Austrian position. D’Arenberg’s reserves, which had just marched to the right flank, were compelled to execute a forced countermarch in the opposite direction. As the troops arrived south of Leuthen, they ran into Prussian infantry units and were badly outmatched during a fierce exchange of musketry. Two Austrian units, disoriented and confused, experienced an unfortunate friendly-fire incident east of the town. Superior Prussian artillery, which had unlimbered on high ground in preparation for a renewed assault, wreaked havoc on the disorganized Austrian formations.

Prince Charles had used the narrow window of time to full advantage. The prince formed a new line, about two miles in length, just north of Leuthen. The Austrian left was now anchored on the forest known as Leuthener Busch, and stretched west to the main highway to Breslau. Additional units had been thrown forward into Leuthen itself, in the hopes that a stern infantry defense of the town would serve to break up the momentum of a renewed Prussian attack. Although the new line had been formed just in time to face the enemy, it was a badly disorganized position that left much to be desired. In some places confused Austrian infantrymen milled about in ranks 100 men deep.

Despite an overall Austrian numerical superiority, Frederick had succeeded in concentrating a preponderance of his highly disciplined army against a badly weakened Austrian flank. By 3:30 pm he was fully prepared to exploit the advantage. With soaring morale after a highly successful afternoon of battle, the Prussian infantry, reorganized in two lines for a fresh assault, marched forward to finish off Prince Charles’ army.

The Austrian infantry stationed in Leuthen, locked in a desperate fight for survival, gave a good accounting of themselves. Fighting fiercely from behind homes, fences, and outbuildings, the Austrians poured heavy fire into the ranks of the oncoming Prussians, who were forced to make their approach over open ground. Thrown back by sheets of well-directed musketry, the Prussians repeatedly reformed and went forward again. Ultimately the sheer weight of numbers began to tell, and as Prussian troops worked their way into the village, the Austrians began to lose their grip.

One outfit of diehards maintained a tenacious grip on the center of the village. A single determined battalion of the Rot-Würzburg Regiment was positioned in the yard of Leuthen’s Roman Catholic church. As their name implied, the Wurzburgers wore distinctive red uniforms and had the honor of their homeland at stake. More importantly, the Catholic churchyard, surrounded by formidable stone walls that sported round turrets in each corner, constituted a ready-made fortress. Well protected by a veritable masonry stronghold, the Wurzburgers were intent on exacting a heavy toll on the advancing Prussians. Their resolution would transform the holy ground of the churchyard into a scene of hellish fighting.

The Prussian 10th Infantry Regiment, which led the initial attack against the Wurzburgers, was badly mauled for the effort. Advancing into heavy fire that poured over the walls of the churchyard, the regiment faltered, broke, and made for the rear. The Prussians reformed and advanced again, but could make no headway against the occupants of the churchyard, who enjoyed excellent protection behind the stone walls. Demoralized and badly bled, the 10th Regiment was forced to fall back. During the day’s fighting, the regiment suffered 700 casualties.

Next to assault the churchyard were elements of an elite guard outfit, the Second and Third Battalions of the 15th Regiment. With a regimental reputation to uphold, the Prussians likewise suffered badly as they struggled to gain entrance into the churchyard. Repulsed with heavy losses, the two battalions reformed and attacked yet again. Finally making headway against the exhausted Wurzburgers in the churchyard, the Prussians succeeded in forcing their way behind the walls. While the third battalion scrambled through a hole in the front wall that had been opened by artillery fire, members of the second battalion forced their way into the churchyard through a side gate.

A bloody close-quarter melee broke out in the churchyard. While the trapped Wurzburgers scrambled to escape the killing ground, they were shot down or bayonetted by vengeful Prussians. The fight for the churchyard was a bloodbath. The two battalions of the 15th Regiment suffered at least 500 casualties in the desperate fight for the church. The Rot-Würzburg Regiment had been decimated: Just five officers and 33 men made it to the safety of the Austrian line. To their credit, the Wurzburgers succeeded in escaping with their regimental colors.

West of Leuthen, the Prussian attack had gone poorly. Lt. Gen. Wolf Frederick von Retzow, one of King Frederick’s favored commanders, nonetheless made little headway. Forced to send much of his own reserves to reinforce the assault on Leuthen, Restow was left short-handed for his own attack. Advancing into the teeth of heavy Austrian fire, his attack ground to a halt before his troops fell back.

On the Austrian right, the situation seemed ripe for a counterattack. General Lucchesi, anxious to get his cavalry back into the fight, observed the exposed Prussian infantry, as well as seemingly poorly defended Prussian guns atop the Butterberg, and decided to launch a full-scale attack with every horseman at his disposal. At 4:30 pm the Austrian cavalry swept down toward the Prussian flank. Lucchesi maintained the hope of crushing Frederick’s left and entirely halting the Prussian advance.

Unfortunately for the Austrian general and his men, the Prussian left-wing cavalry, under the command of Lt. Gen. George Wilhelm von Driesen, lay concealed behind the rolling hills of the Sophienberg. As the Austrian cavalry swung toward the flank of the Prussian infantry, they badly exposed their own right flank. Driesen was quick to pounce. As his men charged out from the cover of the Sophienberg, they caught the Austrians completely by surprise.

The resultant cavalry clash proved a disaster for the Austrians. Lucchesi was felled in the first few moments, and his squadrons were left at a decided tactical disadvantage. Attempting to turn and fight the Prussians that had caught them in the flank, the Austrian cavalry struggled gamely but suffered heavy casualties and were slowly pushed back. Disaster struck when Lt. Gen. Eugene, Prince von Wurttemberg, charged into the fight with 30 fresh Prussian squadrons. Under such overwhelming pressure, the Austrian cavalry finally broke and galloped for the rear in a good measure of confusion.

Close on their heels were exultant Prussian cavalry. Sweeping forward with little opposition, the Prussians crashed into the Austrian infantry’s unprotected right flank. Simultaneously, Prussian infantry on the opposite end of the field pressed forward, lashing around the eastern end of Leuthen and striking the Austrian left. After a day of confusion, reversal, and repeated setbacks, Austrian defenses largely collapsed in the face of such a devastating double envelopment.

The field resembled a charnel house. Prussian cavalry and infantry swept the field, eliminating stubborn pockets of enemy resistance. Isolated groups of Austrian troops fought bravely, but were overrun by superior numbers. Desperate to escape the field, terrified Austrian infantry ran north in a state of panic, littering the battlefield with arms, accoutrements, and their own wounded. A handful of Austrian officers, including the unflappable Nadasdy, kept their heads, rallied frightened troops, and attempted to cover the retreat. For Prince Charles, the battle had degenerated to a complete disaster.

Only nightfall brought a respite from the killing. After darkness fell, Frederick was keen to keep the Austrians from rallying farther north. Intent on seizing the strategically vital bridge over the Wistritz River, the king, joined by a small contingent of hussars and three battalions of grenadiers, pressed forward in the darkness. Narrowly surviving an Austrian ambush, Frederick and his men succeeded in seizing the bridge just before an Austrian detachment was able to set it afire.

The Battle of Leuthen, which is widely considered as Frederick the Great’s most remarkable battlefield achievement, had come at a heavy cost. Six thousand Prussian troops, which was roughly 20 percent of the Prussian army, lay dead or dying. Despite the tremendous cost in blood, Prussian soldiers remained dedicated to their seemingly invincible warrior-king. As his victorious troops marched northeast in pursuit of the Austrians, they spontaneously burst into a familiar song of thanksgiving, the Protestant hymn Now Thank We All Our God. Indeed, they had much for which to be thankful. In the matter of a month, the Prussians had defeated two armies, both of which outnumbered the Prussians two to one.

The magnitude of the disaster for the Austrians was enormous. Their army had lost 130 pieces of artillery and 55 battle flags. The human cost of the fighting was simply staggering. Austrian losses amounted to 3,000 killed, 7,000 wounded, and 12,000 captured. The Prussians forced the surrender of the 17,000 Austrian troops garrisoning Breslau on December 20. Since its field army was no longer effective, Maria Theresa had no choice but to abandon Silesia.

Frederick had distinguished himself as a great military commander on many fields, but Leuthen would come to be regarded as his greatest tactical triumph. No less an authority on military matters than French Emperor Napoleon would weigh in on the Prussian victory. The Prussian victory at Leuthen, asserted Napoleon, was “a masterpiece of maneuver and resolution.”