By Christopher Miskimon

For the United States Army, the long road to Germany began in the mountainous deserts of Tunisia in mid-November 1942. Earlier in the month thousands of GIs had come ashore in the Vichy French territories of Morocco and Algeria. After the brief fighting with French troops ended and a political settlement had been reached, the Americans turned their attention to the east, toward the Germans and Italians. On May 13, 1943, those enemies would capitulate, ending the North African campaign. Although their British allies were seasoned veterans of the desert war, the roughly six-month period between landing and surrender would be a tough one for the U.S. forces. The newly resurgent U.S. Army was taking its first, tentative steps into the realm of modern warfare.

These soldiers had courage, ingenuity, and motivation. What they lacked was experience in ground combat against a battle-hardened, mechanized opponent. Mistakes were made and blunders committed. The GIs learned as they went and suffered accordingly, though they were fast learners. It is actually a testament to them that their first bloody lessons didn’t break them; in a few instances, their perhaps naïve boldness paid off in victory.

A sterling example of such victory is the two-day offensive of Company B, 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion. Part of the first tank destroyer unit to see combat in North Africa, it garnered an impressive tally of enemy tanks knocked out, prisoners seized, and ground taken. What makes this feat even more astounding is that it did so without any support from its higher headquarters; no infantry, armor, or artillery support; and no intelligence whatsoever. The company commander, Captain Gilbert A. Ellman, called it the “absolute absence of any information on the enemy forces.” Nevertheless, Company B was ordered forward to carry out its mission.

Company B was organized along the standard lines of a tank destroyer company of the time. It contained three platoons, each with two sections of two tank destroyers each, for a total of four per platoon and 12 per company. Two platoons were “heavy,” equipped with the M3 tank destroyer, basically a half-track mounting a 75mm Model 1897 cannon (the famous French 75 of World War I) adapted as an antitank gun. A shield was mounted on the cannon to protect the crew from small-arms fire. The other platoon was classified as “light,” using the M6 tank destroyer, a three-quarter-ton truck that mounted a 37mm antitank gun in the bed, also with a thin armored shield.

Earlier in November, an order had been issued to replace the light tank destroyers with the larger, more effective M3s. That order came too late for the units going to North Africa, and they deployed with their M6s, which had only been intended as training vehicles rather than for combat use. Each platoon also had a headquarters section, a two-gun antiaircraft section, and a 12-man security section meant to protect the tank destroyers from enemy infantry. During the company’s mission, it also had a reconnaissance platoon attached from the battalion recon company.

Developed as a response to the whirlwind victories of the German blitzkrieg tactics used so effectively earlier in the war, tank destroyer doctrine of the period dictated that units would block enemy armor penetrations by quickly moving to the point of the breakthrough and using their firepower and mobility to stop the attacking tanks. This doctrine proved flawed in the face of actual German tactics, which were not simple tank attacks but combined arms assaults, with tanks acting in concert with infantry, artillery, antitank guns, and aircraft. It also assumed that field commanders, unschooled in tank destroyer doctrine, had the necessary communications links set up to warn of an enemy breakthrough and could clear jammed rear-area roads for their movement when needed and that a unit of self-propelled guns could simply sit around waiting for such an attack during combat operations.

None of these assumptions proved realistic, and it was the failure of the last assumption that resulted in Company B’s attack. As the U.S. Army moved into Tunisia, it felt its way along, hoping to seize territory and population centers as quickly as possible. This required units with mobility and speed.

By doctrine, Company B had been organized to destroy enemy armor and nothing else, but it did have some hidden strengths. While its tank destroyers were stopgap designs hurriedly placed into service until a more ideal design could be produced, the company did possess a large amount of firepower. Though lightly armored, all its guns were indeed mobile, and the security sections each platoon possessed could double as infantry in a pinch, at least in the view of those unschooled commanders. The tank destroyer men themselves were equally eager for a mission, even one that went against their training.

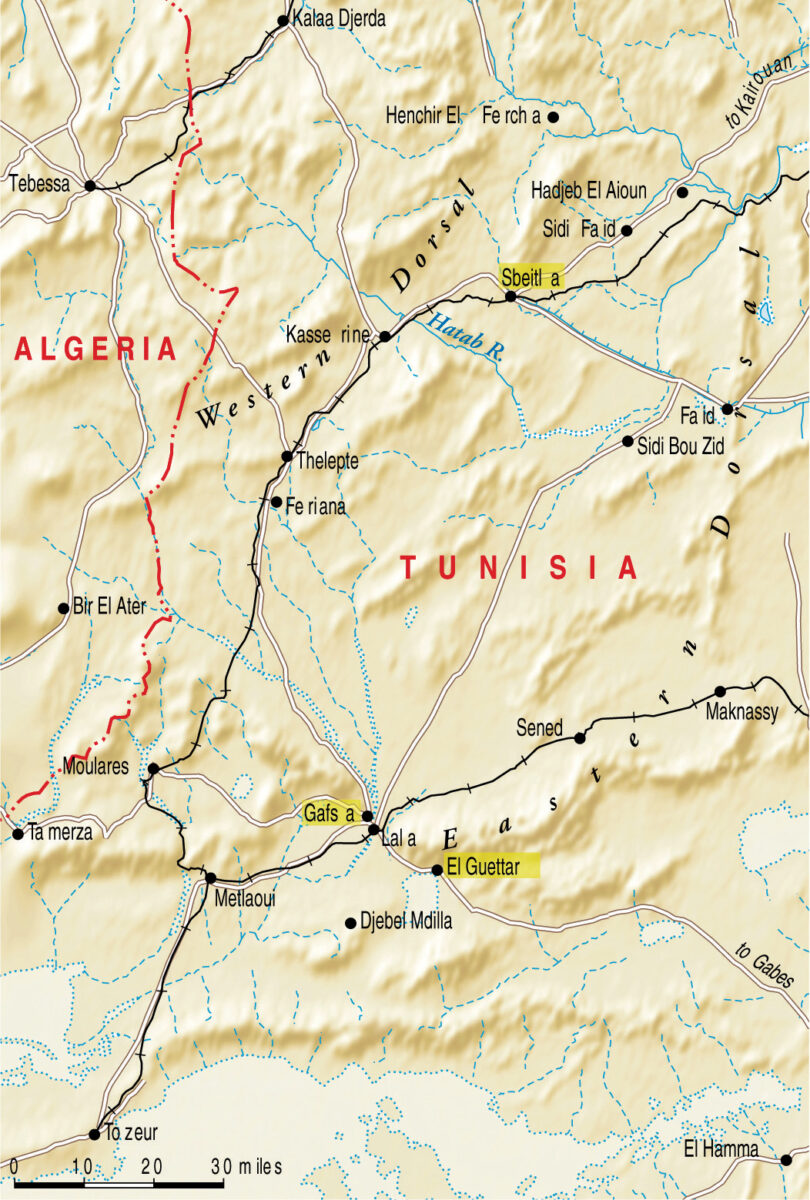

And so it was that Captain Ellman received his orders to take the town of Gafsa on November 22, 1942. His company had just arrived in the area of Feriana, some 47 miles northwest of Gafsa, during the night of the 21st. The previous six days had seen the company moved 1,000 miles from Oran, Algeria. The attack was ordered for dawn. Ellman prepared his unit, refueling and loading ammunition. When finished, the men were able to rest for only a mere half hour before proceeding to the targeted town in a night road march.

Gafsa lies in central Tunisia and is a road junction for routes east to Sfax, southeast to El Guettar and Gabes, and north to the various towns around Kasserine, soon to become famous for the American defeat there. An oasis and a French barracks were located at Gafsa. Ellman had no idea whether anyone even occupied the town, though it was a good bet someone was there. For this first attack, two Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters were to strafe the town before Company B’s assault. Accompanying the tank destroyers was a pair of ancient French armored cars.

The captain organized his company with the two heavy platoons leading the attack, with the light platoon and its vulnerable M6s kept in reserve. Ellman’s account states he had two platoons of M6s, rather than the normal one. Possibly they were attached from another company of the 701st Battalion. There was no cover on the approach to the town, so speed was a key. According to Ellman, “We made the best of a bad situation.”

The P-38s roared overhead, their cannons and machine guns blazing as they strafed the town’s defenders. Company B attacked right on the heels of the fighters, hoping to deny the defenders any time to recover from the aerial assault. The first objectives were two clusters of buildings outside Gafsa itself, on each side of the road leading out of town toward the west and Feriana. One platoon moved to each and immediately began to take fire from German snipers. In response, the tank destroyers began hitting the occupied buildings with 75mm high-explosive rounds. Most of the buildings collapsed after one hit. Continuing past these ruined structures, the two platoons ran into a line of trenches that had been thrown across the road and continued to each side of it. The two French armored cars stayed on the road as they advanced. Both opened fire on these trenches.

This time Ellman and one platoon paralleled the road to the south to avoid mines and advanced directly on the town from the west. The other platoon was sent on a flanking maneuver to the north. Sniper fire continued from the town itself as the tank destroyers moved past the entrenchments. Both of the armored cars, still moving along the road, hit mines. The resulting explosion blew all four wheels off one vehicle, and both were disabled.

Careful to skirt the minefield, Ellman and the accompanying platoon entered the town. Once there, a youthful French civilian approached the GIs and volunteered to show them where the German positions were. Ellman readily agreed, and the boy lived up to his word. As before, high-explosive rounds and machine gun fire answered the German snipers, and the town’s defenders were quickly overwhelmed. The Germans had armed some 300 Arabs to assist in the defense of the town. These men fled into the oasis and groves in and around the settlement, where the Americans had to round them up and disarm them. After a few hours of combat, Gafsa had fallen.

Ellman now took stock of his situation. There were several roads leading to enemy-held territory, so he positioned tank destroyers at each of them to guard against counterattacks. Word of this expected counterattack came just after noon. A German armored column had been spotted moving toward Gafsa from the southeast along the road that led to El Guettar and Gabes. It was quickly decided that Gafsa was not the place to meet a German armored attack because of its terrain, which was not advantageous for a defensive fight. At 2:30 pm, the company advanced toward El Guettar, hoping to find suitable terrain for a defense.

“We hoped to be able to pick our ground and surprise the tanks,” Ellman wrote. He placed his attached reconnaissance platoon in the lead with a heavy platoon behind it. His command group followed with the second heavy platoon behind it. The light platoon brought up the rear. This formation would prove an effective one for Company B throughout its fighting in North Africa.

The Americans covered the roughly 10-15 miles to El Guettar without contacting the enemy. The recon platoon continued through the town to scout the road eastward as the tank destroyers reached its western edge. As the recon vehicles crested a small hill on the eastern edge of town they received a shock. Spread out in front of them was the enemy armored column, its tanks on a second rise farther down the road. The American scouts beat a hasty retreat as the enemy opened fire. One jeep driver turned too quickly, and his jeep flipped over, throwing him and his two comrades into a ditch. They had to crawl back to the town but arrived safely.

The recon troops informed Ellman of the enemy contact, so he sent one platoon to the left of the road and one to the right through the town’s oasis. The light platoon was sent to the south to skirt around the Chott El Guettar, a salt lake outside the settlement. From there it could protect the company’s flank.

The German force contained 10 tanks, and these now proceeded to flank the town to their own right, directly into the path of the heavy platoon Ellman had sent around to his left. The two forces met, and first blood went to the Americans, whose gunners quickly knocked out four opposing tanks. Such heavy losses inflicted so rapidly compelled the German tankers to retreat the way they had come. Ellman’s group arrived at the eastern edge of the oasis just as the six remaining enemy tanks went past on the road. The GI gunners fired a number of 75mm rounds toward the enemy tanks, but they all succeeded in getting past. Though they did not know it at the time, the tank destroyer men had damaged several of the tanks, which were found a few days later, out of fuel.

It was now 1700 hours. With darkness approaching, the men of Company B reformed and went back to Gafsa, hoping for some time to work on their vehicles and get some rest. Unfortunately, it was not to be. As the unit rolled into Gafsa, the men found they had been selected for yet another difficult task. Some 120 miles north of Gafsa lay the town of Sbeitla, which had been occupied by French troops. Earlier in the day, the Germans had reportedly captured the town along with a large cache of supplies and two companies of French infantry. Apparently Company B’s successes had earned it a reputation as a force that could get the job done. The French commander now wanted Ellman to take his men to Sbeitla with a vague order to “do something about it.” Ellman later wrote that such vague commands were normal during the early days in Tunisia, particularly for the tank destroyer units.

The situation was again daunting. Just getting to Sbeitla required another night road march through an area where the front lines were still fluid. At the end of that march, Company B would again have to attack an enemy force of unknown composition and strength, which had been allowed some time to prepare its defenses. Still, the tank destroyer company was the only unit available to do the job, so the men topped off their gas tanks and started back to Feriana, which they reached at about midnight. The light platoon had been left behind to help defend Gafsa. Ellman and his troops got two hours of sleep before starting the final 76 miles of their journey to Sbeitla.

The company used the same formation as before, but with a few modifications to increase its security. The tank destroyers were staggered to each side of the road so each would have a field of fire to the front in case of another engagement like the one at El Guettar. The scouts of the reconnaissance platoon were sent forward and told to be particularly thorough. One M3 of the lead platoon was sent with the scouts so it could support them in case of enemy contact. Its alert crew kept a round in the chamber of its 75mm gun, ready to fire at a moment’s notice.

So disposed, Company B moved northeast, no doubt tense with expectation and fear at the idea of meeting another advancing enemy or, worse, passing one in hiding to find themselves ambushed or cut off. As they moved, the recon platoon checked every likely enemy hiding place for lurking Axis troops or tanks. Any buildings, wooded areas, even clumps of bushes were inspected. After a few hours with no enemy spotted, the unit reached the town of Kasserine. The locals told the Americans that the enemy had reached the town but then fallen back toward Sbeitla.

This increased the tension even more because it meant they were almost sure to find the enemy ahead. Pressing on, the scouts came upon a roadblock some five miles outside Kasserine. Stones had been piled on the road in the saddle between two hilltops. It was a good spot for the enemy to mount a defense to delay any advance on Sbeitla. The recon troops moved cautiously forward, probing for the expected enemy ambush, but found nothing. Inexplicably, the roadblock was not defended or even booby-trapped. The stones were moved off the road, and the company continued on its way.

Visibility grew poor as rain began to fall. After proceeding another 10 miles, the tank destroyer group came to a wrecked bridge that had once spanned a deep canyon. There was no apparent way across. The recon platoon fanned out and soon discovered another crossing point. The men of Company B knew from their maps that they were close to Sbeitla now, approaching from the southwest.

The maps were wrong, however. The road actually came into town from the northwest, a fact the GIs discovered only when the recon jeeps crested the rise of a north-south ridge and found Sbeitla spread out in front of them. An orchard was situated on the western edge of the town, extending from the south side of the road. An old Roman arch was located north of the road at the edge of the settlement. In the distance, another road led out of Sbeitla to the northeast, crossing a large wadi. No fire greeted the jeeps at the rise or as they proceeded toward the orchard. As the Americans later learned, the Italian troops in the town were fortuitously having a meal when Company B arrived. Either they had not bothered to post sentries or those posted were not alert.

The Americans’ luck could not last, though. Just as the approaching GIs began to make out the forms of camouflaged tanks, trenches, and machine gun pits in the orchard, an Italian tanker spotted the Americans and sounded the alarm. The 47mm guns of the Italian medium tanks began to spit shells at the jeeps, and machine guns joined in. The American machine gunners replied, and a fierce firefight developed as the rest of the company now raced to the aid of the scouts. The reconnaissance platoon leader’s half-track, still up near the rise, used its heavy .50-caliber machine gun to cover the jeeps as they pulled back. The attached tank destroyer then opened up with its cannon right over the heads of the men in the jeeps.

Ellman again decided to split his force by platoons, dividing the recon jeeps so they could use their machine guns to support the tank destroyers. One platoon flanked to the left, taking a position at the end of the ridge and opening fire on the orchard. The jeep’s machine gunners fired on the enemy tanks surrounded by the trees. This had a double effect. It kept the enemy tankers buttoned up in their tanks, reducing their visibility, and it marked the positions of the tanks for the tank destroyer crews as the tracer fire ricocheted off their hulls.

The second platoon then moved up to the crest of the ridge some 900 yards from the enemy and began firing on the troops in the orchard, distracting them from the first platoon. This enabled the first platoon to move up to the Roman arch by bounding, one section covering the other as it moved to the new position, where it then provided cover for the other to move. Both sections took up good firing positions near this arch.

Meanwhile, the second platoon had succeeded in knocking out every Italian tank visible in the orchard. The rest of the Italian tanks and infantry now began to retreat into the town. Caught in a deadly crossfire between the two American platoons, more tanks fell prey to the American gunners.

The enemy force was, in fact, a mixed unit of Germans and Italians. The Germans saw the battle turning against their allies and decided to pull out. Manning a number of trucks, they retreated through a rear gate to the northeast road. The three remaining Italian tanks quickly followed the Germans. One tank destroyer from the first platoon tried to move from its position near the arch to cut off the retreating enemy trucks and tanks, braving heavy machine gun fire. The enemy tanks opened fire and succeeded in disabling it, wounding one of the crewmen. This was the only casualty Company B sustained during the entire two-day operation.

A medic was summoned as the Germans and Italians made good their escape. The medic reached the wounded man on foot. Along the way, he had to jump a large ditch. To his surprise, this ditch was full of Italian troops, all of whom surrendered to the unarmed medic.

Ellman now ordered the rest of his tank destroyers to move into the town. They approached cautiously, firing at any enemy they saw. A number of the intersections in the town had enemy machine guns posted nearby. The half-track crews quickly silenced them, sometimes by actually running over the positions with their vehicles. Sbeitla’s remaining defenders surrendered. Company B had fought its third successful action in two days.

One platoon of M3s and a recon section were posted on the northeast road in case of a counterattack. Ellman sent a scout on a motorcycle to bring up a company of paratroopers that was supposed to be following Company B. About 100 Italian soldiers had been captured; these were searched and taken to the rear. Many of the townspeople had been rounded up and secured in two buildings, one for the men, and the other for the women. Curiously, the children had not been collected and many wandered the town, which some Arabs had taken the opportunity to loot. The GIs found a trio of these children wounded and hiding in an abandoned German truck; they were turned over to a town official who himself had just been freed.

A short time later, a French force consisting of a company of infantry supported by an artillery battery arrived to take up the defense of the town. Company B was told to return to Kasserine, where it was finally able to get some rest. Its actions during the preceding two days had resulted in 15 enemy tanks destroyed and more than 400 prisoners taken. The company had covered 400 miles in its movements from Feriana to Gafsa and El Guettar, then back to Feriana before advancing to Kasserine and Sbeitla and finally returning to Kasserine. That it accomplished all this with only one man wounded and two half-tracks lightly damaged is an impressive achievement, especially considering the company’s lack of support during most of its operations.

Company B’s success was also a tribute to the courage and spirit of its soldiers. For men as inexperienced as they were so early in the conflict, they moved with a speed and daring that no doubt contributed greatly to their victories. Certainly, their opponent’s lack of security and defensive preparations contributed to the American accomplishments, but the victories required men with a will to exploit such opportunities despite their relative rawness. Indeed, one could argue that more experienced troops would not have tried such risky endeavors in the same situation. In this case, their boldness paid off.

The towns Company B took and fought in would change hands, in some cases several times, during the remainder of the North African campaign. The ground the tank destroyer men had fought for was shortly to turn into a bloody proving ground for the United States Army, one that would see months of hard combat for the GIs. The small but whirlwind victories accomplished by Company B, 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion during two days of fighting in North Africa are a tiny yet proud moment in that epic conflict.

Christopher Miskimon writes from Denver, Colorado. He has served in both the Infantry and Field Artillery branches of the U.S. Army and is an avid and longtime student of military history. He is a graduate of the University of Maryland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments