By Robert F. Dorr

Ask a member of the 467th Bombardment Group whom they hated most and the answer won’t be Göring or Hitler. Ask a veteran of this B-24 Liberator group what they feared most and they won’t say German flak or fighters.

“It was no contest,” said former Staff Sgt. Vincent Re, an engineer gunner. “By a vote of 100 percent, the man we hated most was Colonel Albert J. Shower.”

During the war, the U.S. Army Air Forces, or USAAF, fielded 243 combat groups, including 125 bombardment groups, of which 72 were “heavy” (four-engined) groups. Of the 243 groups, it appears that only one––the 467th––was formed, trained, taken overseas, taken into battle, led to victory, and brought home by a single commander from start to finish—Shower.

“We hated him,” said Re.

As we shall see, the men’s attitude toward ramrod-stiff, iron-disciplined Shower (West Point, 1932) changed over time. But the object of their greatest fear never changed.

Long after they confronted flak and fighters at altitude over the Third Reich, long after they fought abominable weather, freezing temperatures, and massed Messerschmitts, after they lost friends and won the war, B-24 Liberator veterans of the 467th Group said that nothing terrified them so much as taking off and assembling over East Anglia for the flight to the target.

“We saw planes collide in fog,” said Re. “We saw guys go off the end of the runway and vanish in flames. At times, there were dozens of aircraft filling a very small space in the sky.” Not surprisingly, about half of all aircraft losses during World War II were attributed to noncombat causes. The sky around any bomber base in England was Danger Central.

To increase their chances of survival during a takeoff or assembly mishap, all crewmembers, except the two pilots, strapped themselves down in the Liberator’s waist position until the plane was at cruise altitude. “We huddled back there and we were scared,” said Re.

Bomber Commander

The 467th Bombardment Group (Heavy) was nicknamed the “Rackheath Aggies” after their airfield near Norwich. Among the group’s B-24s was one named “Witchcraft”—a plane so fondly remembered that a restored Liberator, today, is appearing at air shows wearing its markings.

From the moment the 467th Group was activated on August 1, 1943, at desolate Wendover Field, Utah, the atmosphere in the group was different. At other stateside bases, the Army Air Forces (AAF) lived up to its reputation for a casual disregard for military practices and customs.

But in Colonel Albert J. Shower’s outfit, young male adults learning to fly and fight in a 10-man, 32-ton, 215-mile-per-hour warplane bristling with bombs and guns felt they were being treated like boot-camp recruits.

“Here we were flying missions, working with bullets and bombs, and he was always on our backs,” said former 1st Lieutenant Ralph Davis, a B-24 pilot. “When you were not out on a training mission, he would make you fly one. When the weather was bad, he would put you in a Link trainer. We trained and trained and trained.”

Davis said a visiting general shook his head in disbelief at Shower’s insistence on rulebook military procedure, every day, all day. There was little saluting elsewhere in the laid-back AAF, but at Wendover, said the general, “I wear out my goddamned arm saluting whenever I come to this base.”

Here are the raw numbers on what Shower was preparing his B-24 crews for: The United States lost 10,000 bombers in World War II, most with 10 men aboard. The Army Air Forces lost 53,007 men killed in action during the war, more than the total (51,983) for the entire Navy (34,607) and Marine Corps (17,376) combined. Said Shower: “I figured that if being a little ‘too military’ would get one more man through the war alive, it was worth it.”

As with any epiphany that comes to many men, none of the veterans of the 467th Group can pinpoint, exactly, the date and time when Shower went from ogre to idol. After shipping overseas and arriving at Rackheath on March 8, 1944, the “Aggies” flew their first mission on April 10, against a German aircraft assembly plant at Bourges, France.

Though there were no flak or fighters that day, the men noticed something: Shower’s Liberator was leading the formation. The wisdom soon spread that, as Davis put it, “Shower wouldn’t order you to do something unless he could do it himself, and more.” Not every combat group had such a leader, but Shower believed in leading from the front.

As the Eighth Air Force grew and the American daylight bombing campaign broadened, Shower’s B-24 crews began to understand that they were caught up in a new kind of fighting.

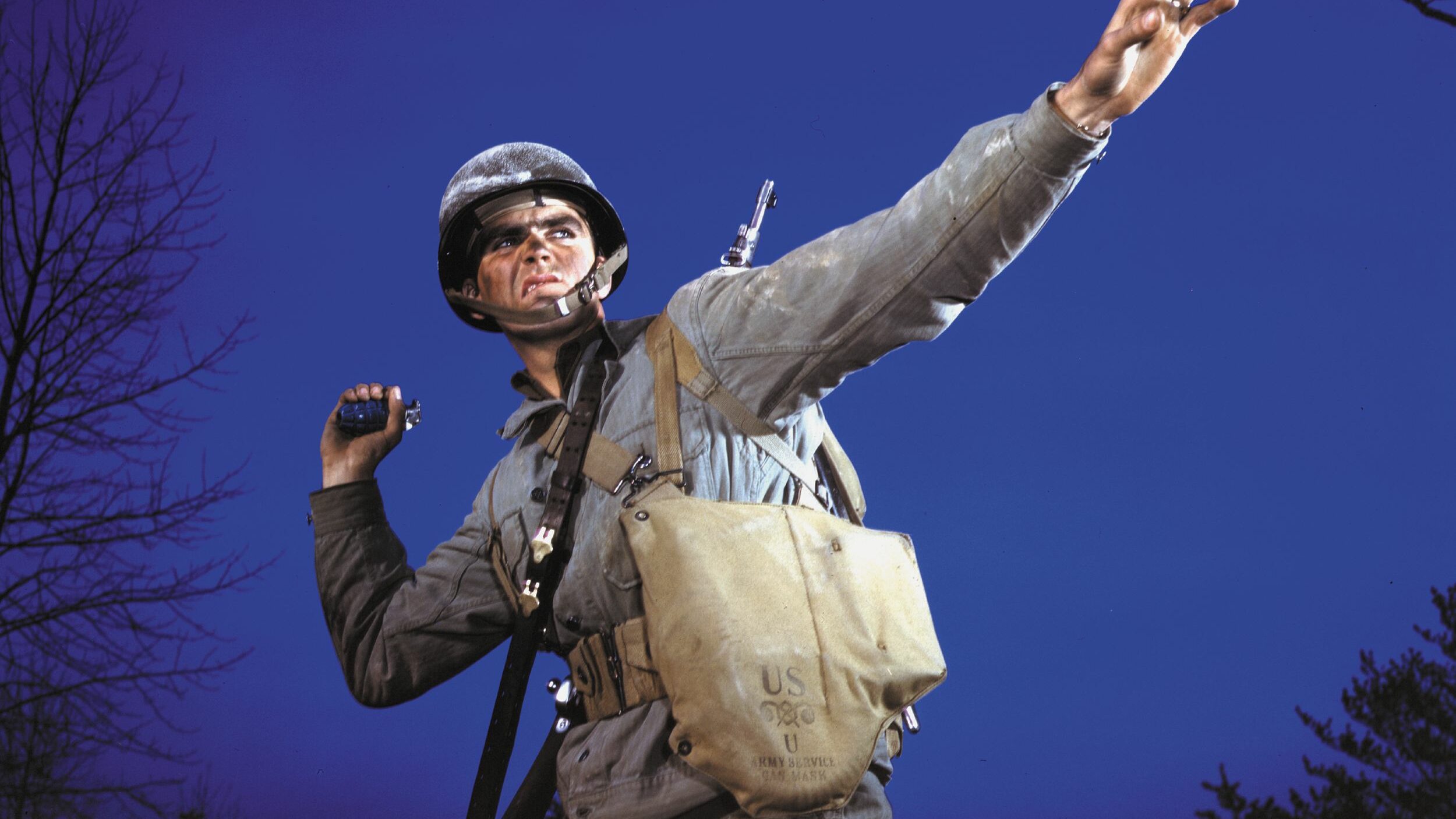

Re, Davis, Shower, and the others routinely waged war at altitudes three times higher than men had been in combat before, in a place where it was always cold, where the temperature could stay far below freezing for hours, and where the air outside the metal skin of their unpressurized aircraft was too thin for humans to breathe. Lose your oxygen and you could die. Lose the electrical connection to your light-blue (“blue bunny”) F-2 four-piece heated flying suit and you could die. Simply do your job while everyone in the Third Reich seemed to be throwing metal at you and you could die. How cold was it up there? One crewman had to tear his penis loose after it stuck fast to the frost-coated relief tube.

How cold was it, really? After a request by Eighth Air Force commander Maj. Gen. (later, General) Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz and endorsement from AAF chief General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, the War Department changed its regulations in September 1943 to define those wounds eligible for the award of the Purple Heart to include any “injury to any part of the body from an outside force, element, or agent sustained as the result of a hostile act of the enemy or while in action in the face of the enemy.” It was the only time in history that the Purple Heart was awarded for frostbite.

A great bomber general who was still a colonel when he introduced tactics over the Third Reich, Curtis E. LeMay, bristled with anger when his bomber missions were characterized as “raids.” The word raid was inadequate, LeMay said. Men in B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators were waging “full-scale battles, fought in the thin air, miles above the land.” By the final months of the war, a typical mission launched 1,400 bombers escorted by 948 fighters.

Pilot Davis witnessed the enormity of these massive air battles firsthand but wasn’t quite sure why he survived them until he bendt down and kissed U.S. soil upon his return from the crucible of the European air war. “Shower made us pilots handle a B-24 like it was a fighter,” Davis said. “Our crews survived when some in other bomb groups didn’t. When you got home [after the war], you began to realize what Colonel Shower had really done for you. Yes, he had been riding your ass constantly. Yes, he had been extremely demanding. But when you survived your tour of duty, you realized you owed your life to this great man.”

Bombing the Reich

After their baptism of fire, Shower’s “Rackheath Aggies” flew mission after mission, facing the cold, fighters, and flak. To a degree, it helped that the Luftwaffe, which was being supplied by German industry with more than enough fighter aircraft, was running desperately low on skilled pilots and struggling to find enough fuel. The really good Luftwaffe pilots, of whom there were far fewer as the war progressed—the Allies defeated the Luftwaffe not by inhibiting aircraft production, nor by shooting down planes, but by killing pilots—perfected a technique of attacking from straight ahead at an angle of 10 degrees above the path of the bomber. This was the location the Americans called “twelve o’clock, high” and its purpose was to kill the bomber pilots.

“But flak was scarier than a fighter,” said waist gunner Sergeant Harold Moore. “You could be hit suddenly. You could be blown apart, or have it happen to someone next to you. One of our B-24 navigators, unscathed by a shattering flak blast, had a crewmate’s severed head come flying into his lap.” And always there was the cold, the bitter, freezing cold that seemed to affect every aspect of existence inside the noisy, trembling B-24. Aboard one bomber, every machine gun froze and was useless just when a swarm of Focke-Wulfs attacked.

Years later, Liberator crew members would resent (or, in some cases, dismiss with a smile) the fact that the B-17 Flying Fortress was world famous. A national poll showed the B-17 to be the “most recognized” aircraft of all time, ahead of the Douglas DC-3, Boeing 747, and Supermarine Spitfire. In contrast, the B-24 seemed almost never to have existed. After the war, few remembered that it was in some ways the better of the two heavy bombers used in Europe.

The B-17 could fly higher, and was easier to handle, more comfortable, more survivable (especially in a water ditching), and unquestionably better looking. But the B-24 was built in far greater numbers (18,325 vs. 12,731), was faster, had greater range, and could carry more bombs. A B-24 flying on three engines could overtake and pass a B-17 chugging along on all four. To be sure, B-17s outnumbered B-24s in the European campaign, but there were 17 combat groups of B-24s, most with four squadrons each, in the theater.

Other facts have been swallowed up in a world of myth and misconception. It simply is not true that the B-17 had an extra crew position for a publicity agent. Rube Goldberg, the 1940s cartoonist who created elaborate machines that didn’t work, was not the designer of the B-24. The Germans in particular, and the Japanese to a lesser extent, made themselves familiar with the aircraft flown by their foes, but they never reached a consensus as to which bomber was easier to attack. Fighter pilots disliked guns on bombers and as the development process continued both the B-17 and B-24 bristled with guns. Neither, however, was regarded as significantly better defended than the other.

You could look in any reference book and get basic facts about the Liberator (first flight: December 28, 1939; power: typically four Pratt & Whitney R-1830-33 Wasp radial engines rated at 1,300 horsepower on takeoff driving a 11-foot, 7-inch, three-bladed Hamilton Standard “spider” propellers; gross weight: 68,500 pounds; maximum speed: 298 miles per hour). But only a 467th Bombardment Group veteran could describe the way the Liberator was transformed in the right hands. “With the right pilot, the plane could be smooth as silk in almost any maneuver,” said Moore. “That was especially true if you had the good fortune to fly with the group commander, Colonel Shower. On the ground, we viewed him as a tough taskmaster. Over a target in Germany, he suddenly handled our plane like magic.”

Rackheath Record

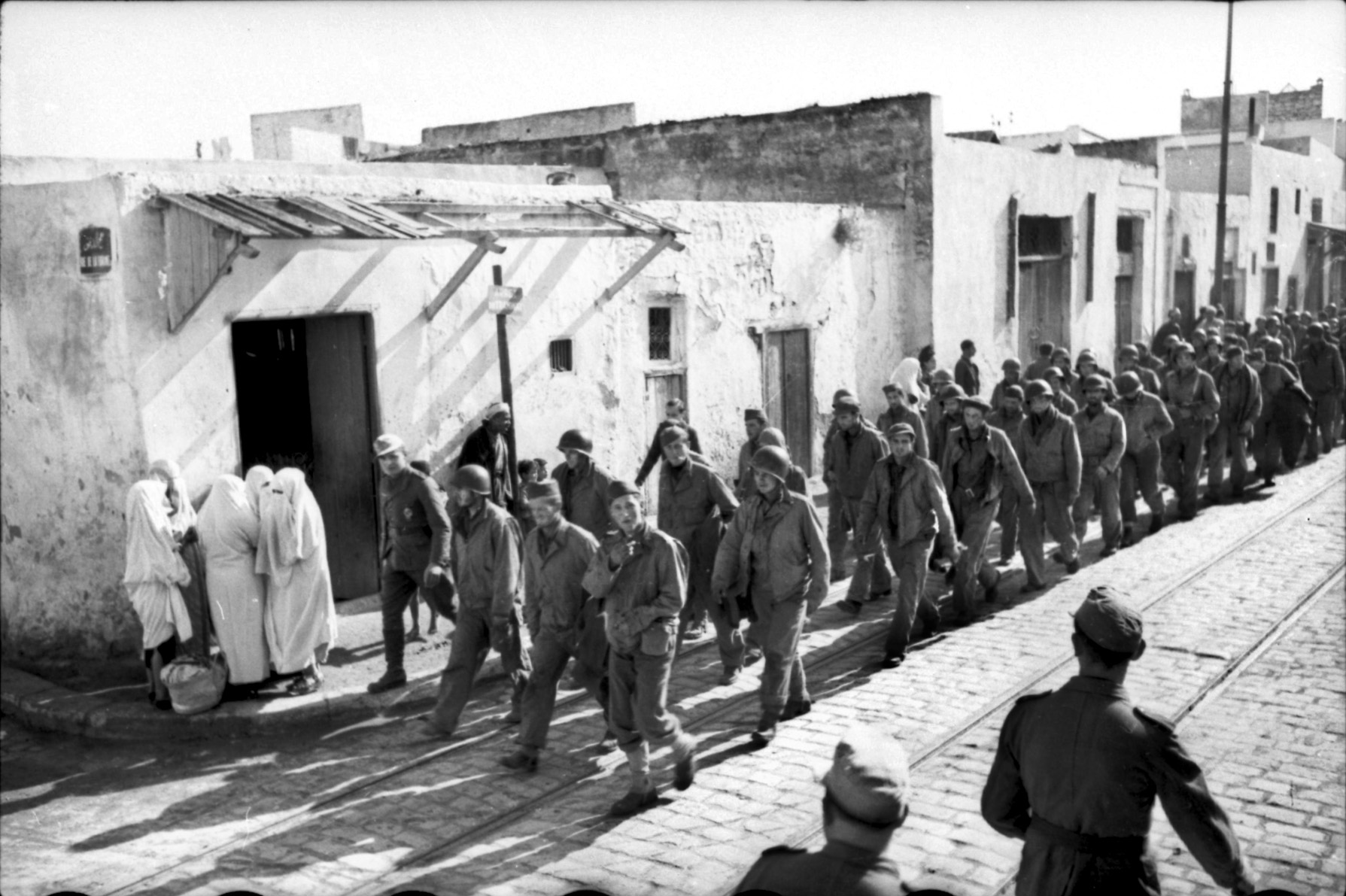

an engineer-gunner on a B-24 Liberator of the 467th Bombardment Group. Re was also a talented photographer who recorded the activities of the “Rackheath Aggies” and their bomber crews. Both men are now deceased.

Shower’s bomb group, its morale high from the moment it arrived in the combat zone, bombed Adolf Hitler’s Reich from April 1944 until the end of the European bombing campaign three weeks before the May 8, 1945, surrender. On April 15, the “Aggies’” final mission to Point de Grave set a record for bombing accuracy, with 24 Liberators dropping 2,000-pounders squarely on a German installation from 21,000 feet.

The Rackheath Aggies’ best-known bomber was “Witchcraft” (B-24H-15-FO 42-52534), which flew 130 sorties without an abort, due in part to hard work by crew chief Sergeant Joe Ramirez. Like so many mechanical veterans of the war, it was not saved after the war ended. However, the Collings Foundation’s Liberator (B-24J-85-CF 44-44052), which has previously worn the colors of two other wartime B-24s, is painted today to represent “Witchcraft.”

Altogether, B-24 Liberator crews of the 467th Group flew 212 missions and logged 5,538 sorties. When all bomb groups were tallied up, Liberators flew 226,775 sorties and dropped 462,508 tons of bombs in Europe.

All of the quotes in this article are from veterans of the 467th Bombardment Group who were interviewed numerous times and who provided documents, photos, and other materials. As we look back at the Rackheath Aggies and their B-24s from the vantage point of the year 2010, the youngest living veterans of World War II are beginning the ninth decade of their lives. Sadly, two who helped most with this article, retired Colonel Albert Shower and former Staff Sergeant Vincent Re, are no longer with us. But as long as Americans can see, hear, touch, and smell a B-24 Liberator, they will live on in our heritage and our hearts.

As an Air Force veteran, it is inspiring to read the thrilling & honorable stories about the exploits of these brave men that were the ones that blazed the trail that we were honored to follow. God bless them!