By Eric Niderost

Generaloberst Erwin Rommel, commander of the Panzerarmee Afrika, was in his element, riding in an armored car at top speed through the desiccated plains of the Libyan desert. It was early evening of May 26, 1942, and Rommel was in the lead as usual, advancing with the vanguard of an armored spearhead he hoped would deliver a crushing defeat to the British enemy.

Rommel was already a legend in his own time, honored by friend and foe alike and dubbed the Desert Fox. He was a familiar figure to both his men and to the German public, thanks to the newsreel cameramen that always seemed to be around to record his deeds and embellish his growing legend. Goggles wrapped around his peaked cap, binoculars hung around his neck, the Iron Cross and the Blue Max—the latter a high award from the First World War—clustered at his throat.

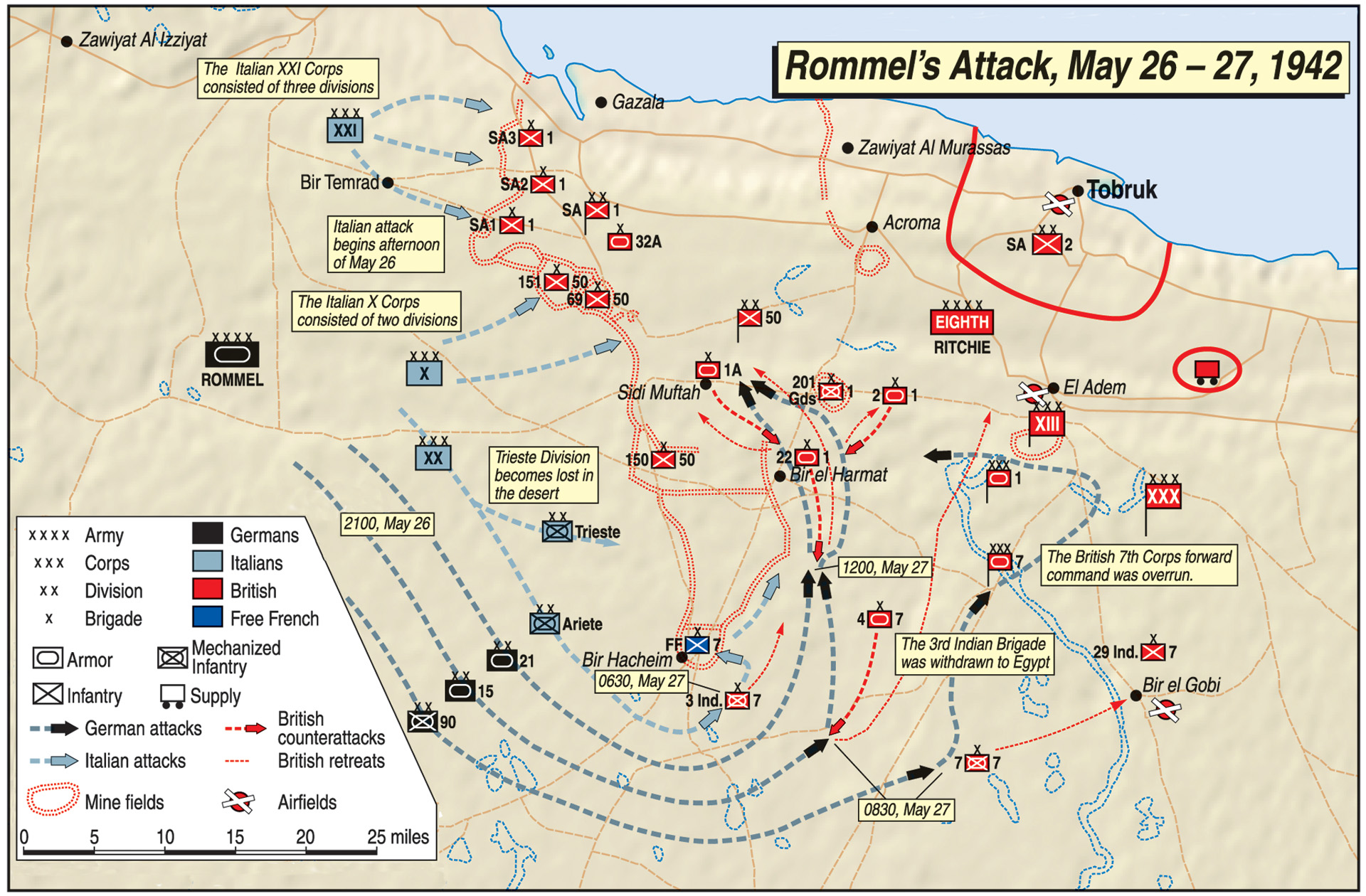

He was leading “Gruppe Rommel,” which consisted of four major elements, all travelling parallel to one another. From left to right there was the Italian 20th Corps, the 21st Panzer Division, the 15th Panzer Division, and finally the 90th Leiche (Light) Division. Counting tanks, armored cars, and support and supply trucks of every size, around 10,000 tracked and wheeled vehicles were following in Rommel’s wake.

The desert at night was usually quiet, but now the engine noises joined with the clattering, grinding, rumbling sounds of tank treads to produce a metallic cacophony that echoed and re-echoed through the night. And that wasn’t all: the leading tanks kicked up the fine-grained, powdery desert sand until great plumes ascended skyward to mark the armor’s rumbling passage.

But these sand clouds also stayed near the ground, a gritty “fog” that was made worse by a dark night. The tank drivers were all but blind in these conditions and had to be guided by tank commanders standing in open hatches, shouting down directions. The commanders themselves relied on compasses, but even so, visibility was so bad there were occasional collisions and near misses. If a vehicle was too badly damaged to continue, it was placed to one side, and the trek wore on. The Germans and Italians advancing with Rommel shared his optimism. He had pulled off near-miracles before—why not again?

The desert war began in 1940, when Italian dictator Benito Mussolini hoped to emulate the successes of Nazi Germany. Sensing a complete Axis victory, eager for his share of the spoils, Mussolini cast covetous eyes on British-occupied Egypt, right next door to the Italian colony of Libya. The British Western Desert Force there numbered only around 63,000, seemingly no match for the 200,000 Italian troops stationed in Libya under Marshal Rodolfo Graziani.

The Italians attacked Egypt in the fall of 1940, but a British counteroffensive quickly turned the tables on Mussolini’s legions. The Italians hardly knew what hit them, and they were sent packing in a headlong 400-mile retreat that did not stop until they reached Beda Fomm. But then the British offensive ran out of steam, in part because Prime Minister Winston Churchill was sending troops to Greece to support the tiny Balkan nation against the Nazis.

But it had still been a humiliating defeat for the Italians, and Hitler felt he must intervene to help his ally. In February 1941, the first elements of the Deutsches Afrika Korps (DAK), or German Africa Corps, arrived in Tripoli. They were commanded by Rommel, destined for desert greatness.

For the next year, the British and Germans fought a see-saw battle in the sun-baked plains of North Africa. Rommel’s first offensive was successful, and he pushed the British back to Egypt, but they reposted with an attack codenamed Operation Crusader. Crusader forced the Germans and Italians to retreat back to Libya. Rommel ended up at his starting point for the 1941 campaign.

There was some fighting in early 1942, but for the most part both sides paused to gather strength for the next round, a clash that might well determine the course of the war in the Middle East. The British Commander in Chief Middle East was General Sir Claude Auchinleck, a man who was widely respected as a good soldier. Unfortunately, he lacked experience in armored warfare, and tanks were the principle means of victory in the desert.

General Auchinleck, affectionately nicknamed “the Auk,” was a man who believed in thorough, even meticulous, preparation before attempting any offensive action. Most of his officers were of the same mind. Unfortunately, Auchinleck had to deal with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was always ready to sack generals if they didn’t share his pugnacious instincts. Churchill knew the war was going badly for the Allies and felt a victory was needed to assuage morale.

The Prime Minister put enormous pressure on “the Auk,” all but demanding an offensive be launched against Rommel at once. When the general demurred, Churchill sent him a curt message that went straight to the point: “Comply or resign.” Almost against his better judgement, Auchinleck promised an offensive in June 1942. It was obvious that the Germans also were going to launch an offensive sometime in the future—but when?

To guard against any sudden German attacks,the Gazala Line was established. This arrangement was a far cry from the unbroken lines of trenches, bunkers and forts that characterized warfare on the Western Front during World War I. Instead, a series of self-contained, self-sufficient strongpoints were strung out like a “necklace” from Gazala on the Mediterranean coast to Bir Hacheim, a distance of some 43 miles.

Each strongpoint, called a “box,” was manned by a full brigade, and each was further protected by tangles of prickly barbed wire and vast stretches of minefields. It was recognized that the Gazala Line could not go on forever, and whatever “box” anchored the end would be of crucial importance to the overall defense. Bir Hacheim was that anchor and was manned by the First Free French Brigade under General Marie Pierre Koenig.

The boxes, sometimes called “keeps” in memory of medieval castle fortifications, had enough food, water, gasoline, and ammunition to be self-sufficient for a week. Each was about one to two miles in circumference, and the minefields and barbed wire were supplemented by slit trenches and pillboxes. Besides the all-important Bir Hacheim, other boxes included strong points at El Adem, Knightsbridge, and Commonwealth Keep.

The Gazala Line was certainly formidable and made the best use of available British forces, but it had a number of inherent weaknesses. The line was long, but it lacked depth. In fact, a second line was starting construction, but the Germans attacked before it could seriously be put in hand. The boxes were also too far apart to be mutually supportive of one another. For example, the 150th infantry box was 16 miles away from Bir Hacheim.

Though “the Auk” was the supreme commander in the Middle East, the British Eighth Army was led by his subordinate, Lt. Gen. Neil Ritchie. Ritchie was another infantryman with no experience in the tactical use of armor in warfare. There was a difference of opinion between Auchinleck and Ritchie when it came to determining German moves. This differing of opinion was going to impact the course of the battle in its early stages.

Richie was of the opinion that Rommel was going to stage a demonstration along the coast road, then head south to go around Bir Hacheim and outflank the entire Gazala line. Auchinlek disagreed, feeling the main German/Italian thrust would be in the north, along the coast road by the Mediterranean. Subsequent events were to prove Richie right.

The Eighth Amy had 100,000 men, with the bulk of the infantry in the strongpoint boxes. The British XIII Corps, largely infantry, included the 50th (Northumberland) Division, the 1st South Africa Division, and the Second South Africa Division. The XXX Corps, Lt. Gen. C.W.M. Norrie commanding, contained the 1st and 7th Armored Divisions.

The Eighth Army had more tanks than Rommel, but the quality was uneven. Some British tank models were prone to mechanical failures, and the main gun was the 2-pounder (40mm), an absurdly lightweight weapon with poor penetrating power for the effective ranges of most battles.

However, the British now had the American made M-3 Grant, which had thick armor, mechanical reliability, and a powerful 75mm gun—better than most German tanks had at the time. It was a stopgap tank, quickly designed and put into production to serve emergency needs. At the time, American industry was still gearing up for war and couldn’t yet manufacture a full turret. For that reason, the 75mm gun was placed in a side mounting called a sponson.

Rommel decided that his offensive would involve two major components: Group Cruwell and Group Rommel. Group Cruwell, commanded by General Ludwig Cruwell, would have the task of staging an attack in the north, along the coast road, exactly where most British officers though it would come. In reality, Cruwell’s advance would be only a feint, a diversion, to disguise the fact that the real blow was going to come via a flanking movement further south.

While Cruwell occupied British attention in the north, Rommel would take the main strike force and head south toward Bir Hacheim under the cover of darkness. Once he circled around and got behind the boxes, he would defeat any armor the British might have in the area and proceed northward. Those infantry strongpoint boxes, outflanked and outmaneuvered, would be helpless to stop him.

Rommel’s immediate objective was Tobruk, the port city on the Mediterranean that had been a thorn in his side in 1941. If it could be captured by the Germans and held, it might then be used as a staging area for the capture of Malta. The possibility that the Eighth Army might be destroyed and a path to Egypt and the Suez Canal be opened were added bonuses.

Rommel’s plans reflected the man himself—bold, innovative, often brilliant, and willing to take calculated risks. But his scheme also had flaws, blind spots that nearly became his undoing. He had absolutely no idea that the British had those new hard-hitting Grant tanks. His ideas on supplying his troops were based on faulty assumptions and bad intelligence reports.

The main strike force was allotted only enough gasoline for 300 miles of offensive action and enough supplies for 96 hours. The Germans envisioned a supply corridor between the northern boxes and Bir Hacheim via the desert tracks of Trigh Capuzzo and Trigh el Abid. Rommel did not know of the existence of the 150th Group Box, which covered those paths.

Rommel also assumed that Bir Hacheim would fall fairly quickly, thus shortening his supply “umbilical chord.”

Rommel’s offensive began with an attack by General Cruwell in the northern section of the Gazala Line, specifically British positions between Gazala and Sidi Mufah. A German artillery barrage started the action, and Luftwaffe Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers plummeted again and again, screaming like metal birds of prey as they bombed and strafed British positions. Cruwell’s force was mainly Italian, consisting of the Sabratha, Trento, Brescia, and Pavia Divisions, supported by a brigade from the German 90th Light.

The tanks kicked up huge clouds of dust, but as the sun sank into the western horizon and the shadows deepened into night, the panzers were replaced by trucks carrying aircraft engines. It was all part of Rommel’s plan to make the British think Cruwell’s attack was the main German offensive. The aircraft engine propellers stirred up massive amounts of sand and debris, resulting in massive cloud plumes that simulated formations of tanks on the move.

Rommel’s push south began seemingly without a hitch. By first light, his panzers had executed a left wheel just south of Bir Hacheim, using that fortress as kind of a pivot. Though Rommel convinced himself that this massive move was undetected, in fact the movement had been spotted much earlier by the 4th South African Armored Car Regiment, which subsequently followed the invaders and relayed every move to headquarters.

Unfortunately, forewarned is not always forearmed, and little was done for hours after reports filtered in. Both General Ritchie and his subordinate General Norrie of XXX Corps were plagued by an indecisiveness that often is fatal in war. Norrie was the one with the bulk of Eight Army’s tanks and armored vehicles and the best chance to stop Rommel’s advance. Both Ritchie and Norrie hesitated, unsure if Rommel’s drive south was a feint.

German and Italian tanks and troops successfully completed the left wheel without incident and were soon speeding northward on paths that were east of the Gazala Line. But they were not going to be unopposed, at least not for long. Scattered elements of the 7th Armored Division, Major General Frank Messervy commanding, were in the area, ensuring a major confrontation in the south.

In the morning hours just before dawn some British units were in the dark both literally and figuratively. The 4th Armored Brigade had been told to move forward at 2:30 in the morning, the better to support both the 7th Motor Brigade and the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade. The 3rd Indian was surprised when attacked by the 21st Panzer and the Italian Ariete Division.

Around 6:30 on the morning of May 27, the British finally got the idea that this southern push was no feint. Brigadier General Anthony A. E. Filose, commanding the 3rd Indian, radioed his superior General Messervy that he faced “a whole bloody German armored division.” They were actually Italian tanks from the Ariete Division, but the comment wasn’t too far off the mark.

The Italians hit hard and fast, and within a half hour the 3rd Indian was wiped out. A few managed to escape, but 450 officers and men were now stunned POWs. The 3rd Indian Motor Brigade’s war diary laconically notes its “positions were overrun.” Happy, and even ebullient, over their victory, the Ariete Division moved on to Bir Hacheim, where they were to find the Free French an entirely different proposition.

The German 90th Light Division made contact with the 7th Motor Brigade about this time, and the results were much the same. Surprised and outnumbered, the 7th Motor tried to regain the initiative by withdrawing into their strongpoint “keep,” the Retma Box. It did little good. The Germans steamrolled their way into Retma with relative ease, capturing the post and sending what remained of the 7th Motor in headlong retreat in a northeasterly direction.

This was Auchinleck’s worst nightmare. Earlier, he had insisted that British armor should not attack piecemeal, in “penny packets” as the saying went, where small unsupported units could be defeated in succession. But this was exactly what was happening, in part because of the surprise of Rommel’s move—it was suspected to be a feint at first—and the size of his southern offensive.

Things were happening so fast General Messervy found it hard to make sense of it all. Confusion reigned; radio reports told of a German advance that was seemingly coming in all directions. The 7th Armored Division’s headquarters were not at a fixed location, but consisted of the general and his staff riding in five armored command vehicles. Merservy got word that German armored cars were coming in his direction, and about the same time shells started to explode around his command car, the dirty blossoms of flame and smoke coming perilously close with each hit.

Three of the command vehicles managed to escape, but a fourth was hit and was quickly engulfed in flames. Moments later a German 30mm shell slammed into Merservy’s car, killing the driver. There wasn’t much more Meservy and his two staff companions could do but surrender. Luckily, they had just enough time to destroy the cypher code books, and the general removed all badges of rank.

Stripped of his insignia and dressed in a shirt and shorts, Merservy pretended to be a simple private, perhaps an orderly to an officer. The ruse worked, though he was almost discovered when a German officer noted his greying hair. “Aren’t you a bit old to be a private?” “Yes,” answered Merservy without a pause, “It’s a bloody disgrace they’ve called me up at my age!” In a scenario that seems more Hollywood than reality, Merservy and his companions actually escaped German captivity the next day.

So far, the German had had things their way. Now, for the first time, they were about to encounter the new M3 Grant tanks in battle. These were tanks of the 4th Armored Brigade, specifically from the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment. The Grants began firing their 75mm guns to good effect, and even when they came within range, the lighter German shells just bounced off the thick metal hides of these lumbering metallic beasts.

Panic started to spread among the men of the 15th Panzer, and Rommel himself later admitted, “The advent of the new American tank tore great holes in our ranks.” Panzer after panzer was “brewed up,” reduced to twisted metal hulks engulfed in flames. The Grants were neutralized to an extent by a flank attack by the deadly German 88mm artillery, so the 3rd Tank Regiment was forced to withdraw to the north.

The 8th Hussars and 5th Royal Tank Regiments came up in succession, and they, too, gave a good account of themselves before being compelled to withdraw. Even with the Grants, single battalions fighting in piecemeal fashion against entire panzer divisions was not the way to victory. But the Germans had been taught a sharp lesson and had lost many tanks in the process.

The 7th Armored Division was essentially out of the action, with many formations destroyed or scattered and badly in need of regrouping. The 1st Armored was the Eighth Army’s last hope, and it did rise to the occasion. After very heavy fighting, it managed to blunt, if not altogether stop, Rommel’s drive.

The Desert Fox’s plans were starting to unravel just when he seemed to be on the brink of his greatest success. His panzers were running perilously low on fuel and ammunition, and even water—that key ingredient in desert warfare—was in short supply. Bir Hacheim had not fallen, which meant the Germans had to travel extra miles to avoid that dangerous obstacle, and also meant waiting extra time for depleted stores to be replenished.

The next day, May 28, the fighting resumed with new intensity. The Germans ignored their supply problems, if only for the moment, and pushed on. The 21st Panzer reached Commonwealth Keep, a box that was near the Sidra Ridge, but still short of the Mediterranean by about five miles. There was some small good news: the Italian Motorized Division “Trieste” had cleared a path through an undefended minefield just north of Bir Hacheim. It was a narrow trail, but a shorter route for supply trucks to get through to Rommel.

The new path helped, but the trickle was still not enough to fully ease the increasingly critical supply situation. The bulk of Rommel’s forces were still east of an undefeated and generally unbroken Gazala Line. Rommel had delivered a series of powerful blows, but even after tank losses the British still outnumbered him in men, materiel, and armor. And the Panzerarmee Afrika had not emerged unscathed; perhaps a third of its panzers were out of action.

Rommel’s men were also running out of water, and not enough was getting through to supply basic needs. A British POW, Major Archer Shee, personally complained to Rommel that he and his fellow prisoners were only getting a half a cup of water a day. “It’s the same as we get,” replied Rommel, “but I agree this can’t go on forever. If we can’t get a convoy in tonight, I’ll have to ask General Ritchie for terms.”

Some water and supplies did reach the Panzerarmee, and at one point Rommel personally led a supply convoy through to his troops. But the Desert Fox was at bay, and it was during this period—around May 28 to June 1—that he was at his most vulnerable. But timing is everything in war, and Ritchie launched major counterattacks on June 3, which were repulsed with heavy fighting.

Necessity is supposed to be the mother of invention, and it certainly must have seemed that way to Rommel. He decided to “fort up,” going on the defensive with British boxes and minefields all around him. He wanted German engineers to clear a broader supply path to the west, an action that would simultaneously breech the Gazala Line. While the engineers worked feverishly to accomplish this task, a ring of German 88mm artillery would fend off any British armor attacks from the east.

But there was a major problem—the path the engineers were carving out was perilously close to 150 Box. Artillery shells from that box rained down constantly, slowing progress and producing German casualties. While Ritchie dithered, trying to decide the best course of action in light of an ever-changing situation, Rommel threw the whole weight of the Afrika Korps on 150th Brigade box, which fell after heroic resistance on June 1.

British responses were also hampered by the weather. Howling winds kicked up powerful sandstorms on June 1-2, the yellow clouds of sand particles obscuring everything in their path. A major Eighth Army counteroffensive, Operation Aberdeen, was launched on June 5, but it ended up a fiasco of major proportions. Something like 150 tanks were lost, victims of the deadly German 88s, and 4,000 men were taken prisoner.

Rommel now turned his attention to Bir Hacheim, determined to remove that thorn in his side once and for all. There were around 3,600 men at Bir Hacheim, many of them in the celebrated French Foreign Legion, and they were determined to erase the shame of the 1940 defeat at the hands of the Germans.

General Koenig was a tough old soldier, as determined to hold out as his men, but he did have had some further comfort in his chauffeur and lover, Mary Travers. She was English, daughter of a wealthy businessman, and before the war had been a beautiful socialite addicted to parties, champagne, and lovers. But when the war broke out, she turned serious, and became a nurse and later a chauffeur. Though Travers and Koenig became lovers, she refused to be left behind when he was assigned Bir Hacheim.

Day after day, the Germans pounded Bir Hacheim with artillery and Stuka dive bombing attacks, followed up by land assaults. The fighting was often hand-to-hand, and though the defensive perimeter shrank, it did not break. The British somehow managed to get a trickle of supplies and ammunition into the beleaguered garrison, but it was clear the Germans had the upper hand.

On June 10, General Ritchie ordered the Free French to withdraw from Bir Hacheim. Evacuation was done under the cover of darkness, but eventually the Germans discovered the movement and all hell broke loose. The French had to run the gauntlet of German machine-gun fire and artillery shells. General Koenig’s car, Mary at the wheel, at one point paused at a large shell hole, and in the darkness the passengers heard German voices all around them.

Travers later recalled, “Tracer fire started coming at us … We had to drive as fast as we jolly well could in the pitch dark … We got through, almost the entire brigade. I had eleven bullet holes in my car, but we made it.” The fall of Bir Hacheim was a major psychological blow to British morale. British counterattacks had been badly timed and badly executed, though fought with great courage.

Both sides were exhausted, but Panzerarmee Afrika now had the momentum for victory. The British XXX Corps was down to 70 tanks and seemed to be on the verge of collapse. Panzerarmee Afrika had even fewer, with the Germans fielding just 44 tanks and the Italians around 14. But Rommel had smelled victory, and nothing was going to stop him now. A few days later, Tobruk, that symbol of British resistance, fell to the Germans.

Auchinleck felt the battered Eighth Army needed precious time to rest and reorganize, so he ordered a withdrawal to Egypt, there to secure a line between the Qattara Depression and El Alamein. As the British withdrew to the east, their headlong flight was dubbed the “Gazala gallop.” By June 30, 1942, all British units that were capable of escape had done so.

Gazala was Rommel’s greatest triumph, but even his tactical genius and audacity could not overcome logistics and geography. Adolf Hitler was preoccupied with the Russian front and looked on North Africa as a sideshow scarcely worthy of his attention.

And in Egypt, the great Qattara Depression meant that the bold flanking moves that the Desert Fox relished would be a thing of the past. That November, Rommel was decisively defeated at El Alamein.

Author Eric Niderost is a frequent contributor to WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in Union City, California, where he is also a college history professor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments