By William E. Welsh

By the Summer of 1864, it was no longer likely the Army of Northern Virginia would invade the North a third time, would launch another major offensive, or even drive Union forces away from Richmond and Petersburg. The Army of Northern Virginia’s only real hope lay in inflicting enough casualties on the Union armies to force the U.S. government to the peace table.

While General Robert E. Lee focused on winning the war in the trenches, two Confederate agents explored ways they might inflict severe damage on the sprawling Union supply depot at City Point where General Ulysses S. Grant had established his headquarters. The supply depot, located at the confluence of the James and Appomattox Rivers, supported upward of 100,000 Union soldiers and 65,000 animals following the start of the siege of Petersburg in June 1864.

Approximately 225 ships arrived daily at the supply depot to unload ammunition, food, building materials, and other equipment needed by the Union Army. A long warehouse made of pine paralleled the wharf and ran the length of it. On the opposite side of the warehouse from the wharf was a railroad track. The tracks ran from the warehouse to the front lines at Petersburg. The supplies were unloaded from the ships into the warehouse and then onto the railroad cars. By August, 275 railcars had been sent by boat from Washington to be used to transport food, ammunition, and equipment to the front.

A short walk beyond the railroad track was a row of buildings that included a post office, quartermaster’s office, and Sanitary Commission office. In addition, sutlers had set up their tents and stalls in that location. Beyond the depot buildings at river level rose a tall bluff where the Eppes mansion was situated. The family had owned the tract for more than two centuries. Grant had established his headquarters on the grounds of the estate. The hilltop was covered with tents and frame cabins belonging to Grant’s staff and various other Union troops. The commissary troops kept three million pounds of food stored on site in an effort to ensure that soldiers and horses could be supplied for one month in case the Confederacy managed to launch a successful attack by land or sea on the Union Army’s supply lines.

The Union Army went to great effort to protect its massive supply depot from Confederate raiders. Union soldiers had built an impressive fortified line around it that was studded with redoubts and watch towers. Artillery emplacements covered all the approaches from the James River. Sentries were on duty around the clock, and during the daytime hours they used field glasses to scan the countryside and river from their high perches. A successful attack by a Confederate raiding party would be an extremely difficult venture with little hope of success. But subterfuge might succeed where direct assault was not feasible.

Not long after the Union Army ramped up the City Point depot to support the operations of the Army of the Potomac before Petersburg, Captain Z. McDaniel of Company A of the Confederate Secret Service ordered Scottishborn Virginian John Maxwell to carry out an attack against Federal shipping on the James River using horological torpedoes; that is, bombs set off with a timing device.

Maxwell was no neophyte when it came to attacks against Union targets. He had extensive experience raiding Union shipping on the Chesapeake Bay in 1863 with privateer John Yates Beall. The bold privateer had carried out attacks with a band of about 18 compatriots aboard two boats, the Raven and the Swan. Union forces captured Beall in November 1863, but he was exchanged on May 5, 1864, at which point he focused his efforts on targets in the Northeast. Maxwell had served under Beall during his raiding days on the Cheseapeake. Maxwell’s reputation preceded him, and the leadership of the Confederate Secret Service had complete faith in him.

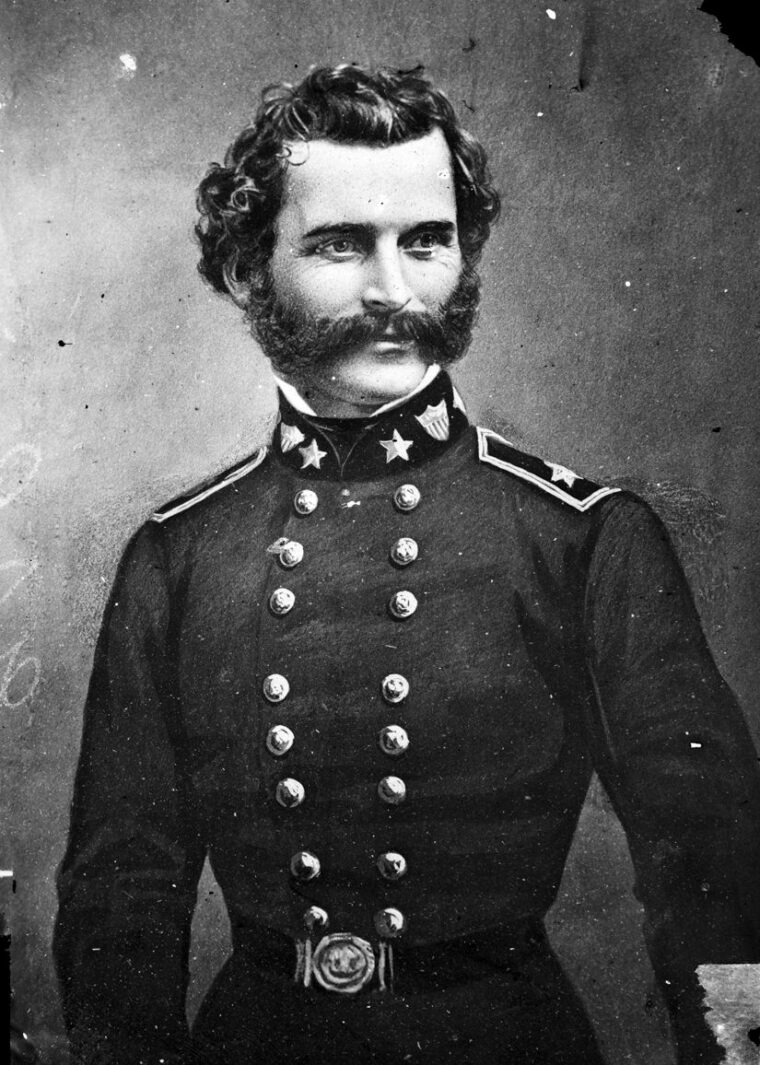

Brigadier General Gabriel James Raines of Noth Carolina headed the Confederate Torpedo Bureau. In Civil War lexicon, “torpedo” was a general term for naval and land mines. Raines, who graduated from West Point in 1827, showed an early aptitude for explosives. While serving as commandant of Fort King in central Florida in 1840 during the Seminole War, he constructed a torpedo designed to foil Indian ambushes. His device consisted of an artillery shell with a detonating device. He resigned from the U.S. Army and was commissioned on September 23, 1861, as a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. During the Peninsula Campaign, he commanded a division in the Army of the Peninsula.

mentations with mines between that point and the outbreak of the Civil War, he and his men deployed land mines, known as subterra shells, in the path of the Union advance as the Confederates began withdrawing from Yorktown on May 3. The following day Union soldiers inadvertently detonated some of Raines’ torpedoes. Raines designed and manufactured his own sensitive primers, which he attached to artillery shells to make land mines. Some members of the Confederate government and high command initially balked at the use of torpedoes in this manner, but they eventually embraced it as a way to offset the tremendous manpower and equipment advantages of the Union Army and Navy.

Raines was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. When General Robert E. Lee assumed command of Confederate forces around Richmond, he asked Raines to oversee the mining of the James River to prevent Union naval forces from penetrating it as far as Richmond. When the Confederate Congress established the Confederate Torpedo Bureau in October 1862, Raines was an obvious choice to head the nascent organization. He eventually was vested with the authority to oversee all mine warfare endeavors throughout the South. During his tenure, he developed a system of torpedoes and mines that were used to protect Southern-held waterways, cities and ports, and field fortifications. He also developed a functioning land mine.

While Raines directed the Confederacy’s Torpedo Bureau, his younger brother, George Washington Raines, directed operations at the preeminent Augusta Powder Works and Arsenal. Together, they became known as the Bomb Brothers. Naturally, the elder Raines could not personally oversee, much less carry out, all of the individual acts of laying naval and land mines for the Confederacy, and for that reason he and his staff trained and furnished materials for those who carried out individual efforts, particularly those bombing or booby-trap missions that were carried out as part of raids or sabotage against Union military infrastructure and equipment.

Brigadier General Raines ordered and approved the saboteur mission that Confederate Secret Service agent Maxwell would carry out against City Point. Captain McDaniel supplied Maxwell with a box loaded with 12 pounds of explosives and a timer. The explosives were stored in an innocuous candle box that had been purchased from a country store. Maxwell departed Richmond on July 26 accompanied by fellow agent R.K. Dillard, who had extensive knowledge of the James River environs. To elude Federal patrols, the two agents travelled under cover of night as much as possible.

The two agents wanted to cause as much damage as possible. On August 2 they learned that Federal ships were in the process of unloading a large shipment of supplies to City Point. Their slow progress from Richmond to City Point stands as proof of the difficulty they had infiltrating the tightly guarded river depot. It is safe to assume that they were assisted by other Confederate agents who lodged and fed them as they prepared to infiltrate the City Point depot. Maxwell’s aim was to inflict maximum damage to the cargo ships by placing his time bomb in close proximity to ammunition supplies.

On the morning of August 9, the two agents managed to penetrate the eastern perimeter of City Point by crawling through the lines in a way that avoided detection by the Union sentries. Maxwell told Dillard to wait a half mile from the pier while he attempted to smuggle the bomb aboard one of the vessels. Maxwell saw three vessels tied up at the pier. When the captain of one of the vessels went ashore, Maxwell strode confidently toward the vessel in an effort to blend in to the everyday foot traffic at the pier. Suddenly, a sentry on the wharf hailed him in German, inquiring as to his business. He responded in a thick Scottish accent. Maxwell used various hand gestures to indicate his mission, and the sentry allowed him to approach the vessel.

The ruse having worked, Maxwell hailed a man who clearly worked on the vessel. He told the crew member that the captain wanted the box he was holding taken below deck. The man complied without questioning the contents. Maxwell set the timer in motion with a subtle movement at approximately 10:30 AM and gave it to the man who dutifully carried it aboard the vessel. The vessel turned out to be an ammunition boat named the J.E. Kendrick. The other two ships were the General Meade and the Campbell. Maxwell then walked back to Dillard, and together the two agents walked a safe distance from the bomb to watch the explosion due to occur in an hour’s time.

The explosion at approximately 11:30 was devastating in its destruction and terrifying to everyone at the depot that morning, including the soldiers and officers at the Eppes estate. Lieutenant Morris Schaff, who ran the ordnance depot at City Point, wrote an account 35 years later that gives a comprehensive overview of the damage wrought by Maxwell’s time bomb that morning. The event was no smalltime endeavor. Raines and his agents had been perfecting their mines and bombs for three years, and the damage inflicted by the bomb was in some respects the culmination of many months of experimentation and of their efforts to fine-tune the tools of their trade.

At the time of the explosion, Schaff was relaxing and playing the card game known as Seven-up with three other officers. A 12-pound solid shot flew between them and slammed into a camp chest. The officers rushed to see what was happening. Ammunition stores on the J.E. Kendrick were cooking off, and those shells in turn ignited other piles of ammunition. The J.E. Kendrick had aboard it upward of 30,000 rounds of artillery ammunition and 100,000 rounds for small arms. All of the soldiers, sutlers, and civilians near the dock were stampeding away from the pier in an effort to put as much distance as possible between them and the expanding disaster.

“The sky looked as it does in the fall of heavy snowflakes,” wrote Schaff. “Just then a shell burst immediately above us. In an instant we were all running for dear life…. Suddenly a piece of shell came down over my shoulder. I could have stepped on the hole it made in the ground, but it brought me to my senses, and I at once turned and made my way to the wharf.”

In addition to the exploding shells, various other kinds of debris, such as rifles, rained onto the ground or into the river following the initial explosion. One of the more curious incidents involved a canal boat loaded with horse saddles that was situated in close proximity to the J.E. Kendrick when it exploded. The saddles had been turned in by Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s cavalry a few days before when they embarked for Washington to redeploy in the Shenandoah Valley. “The explosion sent those old cavalry saddles flying in every direction like so many big-winged bats,” said Schaff.

A New York Tribune correspondent was aboard a train waiting to go to the battlefront when he experienced the blast concussion. “A stunning and deafening shock, as if of the terrific explosion of a monster shell near me, and the concussion of the air, were bending me involuntarily over on the deck of the car, as a plant bending before the storm, and it seemed that the concussion would never cease ringing and swaying until it bred more and more danger,” he wrote. The freight train that he was aboard suffered damage to nearly every one of its cars, he said.

“My first thought was that an ammunition car had exploded just ahead of the one I was on, and that it would be of little use to try to escape the storm that had gone up and would come down [and] that one was about as safe at one place as another,” said the correspondent. “But the dread storm did commence coming down, and oh how it did rain and hail all the terrible instruments of war…. We could only shelter our heads with our hats and our hands as we walked aft.”

While nearly everyone was fleeing from the carnage, Schaff went to see if he could help the wounded and also prevent additional explosions. When he reached a vantage point from which he could see the full breadth of the devastation, Schaff was overwhelmed. “From the top of the bluff there lay before me a staggering scene,” he said. “[I saw] a mass of overthrown buildings, their timbers tangled into almost impenetrable heaps. In the water were wrecked and sunken barges, while out among the shipping, where there were many vessels of all sizes and kinds, there was a hurrying back and forth on the decks to weigh anchor, for all seemed to think something more would happen.”

He made his way to a wooden building that lay in ruins. He and some of the noncommissioned officers began digging out those who were trapped and crying out for help. A corporal shouted for help, and they pulled away heavy timber that had fallen on top of him and pinned him to the ground crushing his legs. Someone shouted that another explosion was going to happen any minute as fire was about to reach a stack of ammunition boxes. This started another stampede. But Schaff bravely rushed over to the fire and beat it back with his hat before it could ignite the stack.

Grant was sitting in front of his tent on the bluff overlooking the wharf when the bomb exploded. Ironically, the assistant provost marshal general had briefed the general earlier that morning on the suspected presence of Confederate spies on the depot grounds, and he also suggested methods for identifying and arresting them.

The explosion “vividly recalled the Petersburg mine,” said Horace Porter, Grant’s aide, referring to the explosion carried out by Union forces on July 30 against a portion of the Confederate earthworks at Petersburg in what ultimately was a failed effort to achieve a breakthrough. “There rained down upon the party a terrific shower of shells, bullets, boards and fragments of timber. The general was surrounded by splinters and various kinds of ammunition, but fortunately was not touched by any of the missiles.”

Grant reacted to the explosion with his customary stoicism. “The general was the only one of the party who remained unmoved,” wrote Porter. “He did not even leave his seat to run to the bluff with the others to see what happened.” Instead, Grant went to his camp desk and began drafting a report to Washington.

Grant promptly sent a quick report by telegraph informing Army Chief of Staff Henry Halleck of the incident. “Five minutes ago an ordnance boat exploded, carrying lumber, grape, canister, and all kinds of shot over this point,” wrote Grant. “Every part of the yard used as my headquarters is filled with splinters and fragments of shell. I do not know yet what the casualties are beyond my own headquarters…. The damage at the wharf must be considerable in both life and property.”

The ferocity of the explosion startled Maxwell, too. “I myself was terribly shocked by the explosion, but was not injured permanently,” he wrote. “Dillard, my companion, was rendered deaf by the explosion and never fully recovered from its effects.” Maxwell said he had one major regret. “[I learned] a party of ladies was killed,” he wrote. “Of course, we never intended anything of the kind, not being aware of their presence.”

The U.S. government estimated the damage at $2 million. Although the precise number of casualties is not known, the best estimate at the time was that 58 people were killed and 126 wounded. A boat had departed that morning for Baltimore, and if the explosion had occurred earlier in the day the casualties would have been much greater, said Schaff. At the time, the Union Army attributed the explosion to the mishandling of ammunition by the porters who were unloading it, said Porter. It was not until after the war that they learned it was a deliberate act of sabotage. It took Union army work crews only nine days to clean up the damage and repair the docks to the point that supplies could flow into the depot at the same rate they had before the explosion.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments