By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

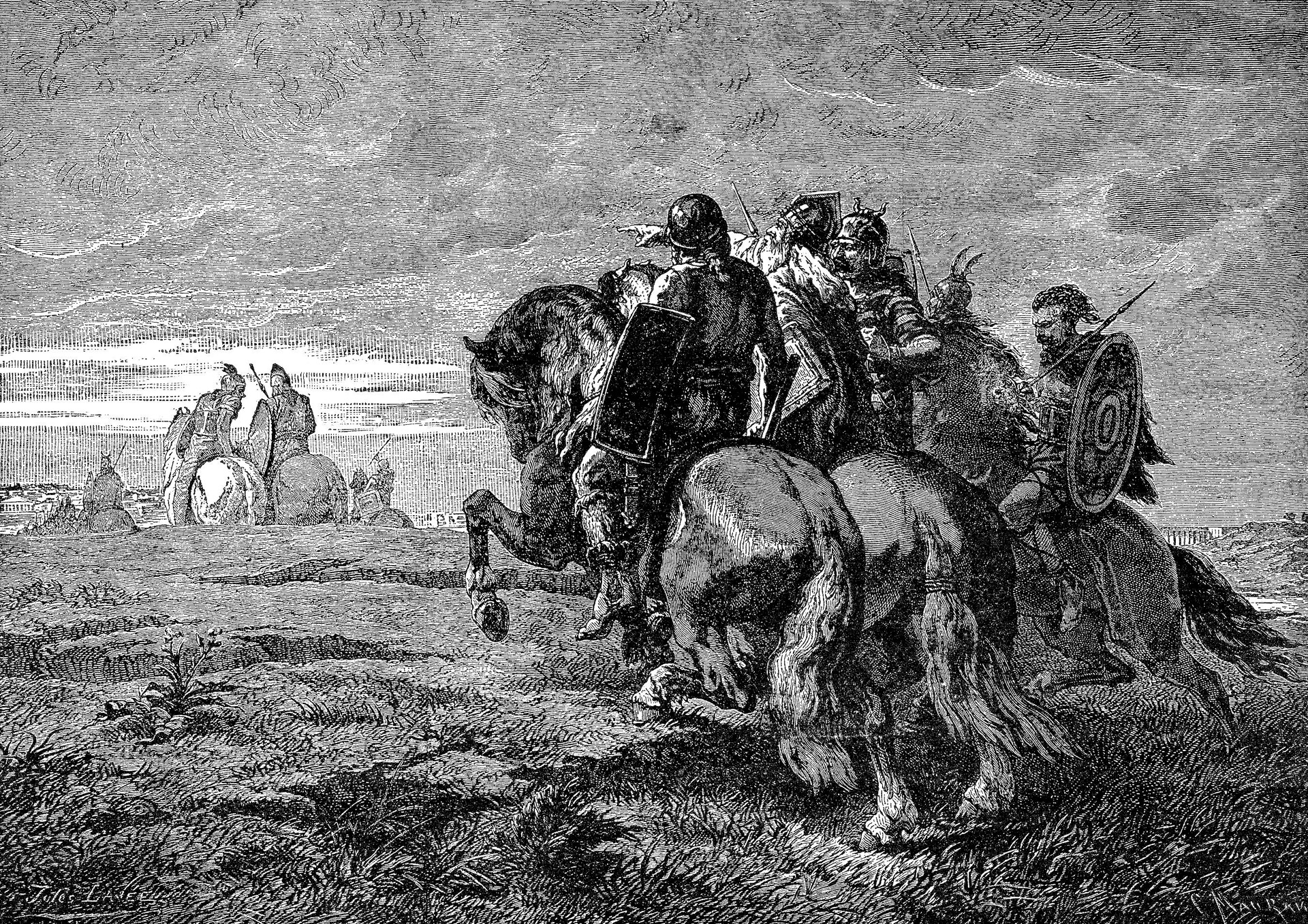

Gigantic clouds of dust rose from the sun-baked plain. The ground shook under the hoofs of thousands of cavalry. The young Roman commander Publius urged on his steed. Ahead of him fled the Parthian cavalry that had assailed the army of his father, Marcus Licinius Crassus. In 54 bc, the elder Crassus had led his legions into Parthian-held Mesopotamia. Despite having been shook by civil wars, the Roman Republic continued to expand. Empires and kingdoms, fierce barbarian tribes, all had succumbed. Publius heartily shouted that the enemy fled in fear. His bold words raised the spirits of his men, fierce barbarians from Gaul, allies of Rome, alongside cavalry levies from Syria. To Publius it looked as if the Parthians were destined to fall against the might of Rome just like all other foes.

Although the Parthian Empire had been around for centuries, relations with Rome had remained peaceful for a long time. The rise of Parthia began in the mid-3rd century bc when the Parni, a nomadic tribe related to the Persians, settled on the northern edge of the Persian plateau. The region they settled in was known as Parthia. The Parni nobles, the Arsacids, built Parthia into a powerful kingdom. The Arsacids were fortunate that the dominant power in Persia, the Seleucids, was in decline.

One of the successors of Alexander the Great, the Seleucid kingdom became fatally weakened in a war with Rome early in the 2nd century. But since Roman interests in the Middle East remained limited, the Parthians were left free to wrest Persia from the Seleucids. In 129 bc, the Arsacids set up their royal residence at Ctesiphon, across the River Tigris from Seleucia, the kingdom’s former capital. By the end of the 2nd century bc, the Parthians lorded over Mesopotamia. By subjugating vassal states, the Arsacids had built an empire.

In 66 bc Parthia allied itself with Rome against the common foe of Armenia; however, after Armenia’s defeat, the Roman commander, Gnaeus Pompeius (Pompey), rescinded on his promise to restore Mesopotamian lands occupied by Armenia to Parthia. From that point on there was bad blood between Rome and Parthia. In 56 bc, Gabinius, the governor of Roman Syria, supported a rival claimant to the Parthian throne but undertook no military intervention. But in 54 bc a new governor arrived in Syria, one who was eager for military laurels. Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of the most powerful men in Rome, had come to conquer Parthia in a bid to burnish his reputation as a commander and further his personal glory.

In 115 bc, the elder Crassus was born into the old and respected plebeian gens Licinia. Crassus had a distinguished career and was a gifted political orator but his chief asset was his immense wealth. In the First Civil War, Crassus had sided with Lucius Cornelius Sulla against his rival Gaius Marius. The latter unleashed a killing spree in Rome that claimed the lives of Crassus’ father and brother. Crassus hid out in a Spanish seaside cave, and then rejoined Sulla in the Second Civil War. At the Colline Gate, Crassus clinched Sulla’s decisive victory over the Marian faction.

During Sulla’s dictatorship, Crassus profited from those despoiled of their possessions. Crassus bought property on the cheap, which had been destroyed by fire or which had collapsed. Controlling a fire brigade made up of his slaves, Crassus let buildings burn until the owner agreed to sell. Crassus made a fortune through land speculation, silver mines, and immense farms. Crassus’ greatest material assets were his slaves. His slave holdings included not only countless laborers, but also hundreds of architects, artisans and other skilled professionals. Upon receiving the consulship in 70 bc, Crassus sacrificed one-tenth of his wealth to Hercules, gave public feasts and paid the basic expenses of every Roman for three months. The vast expenditure hardly dented Crassus’ fortune, which still amounted to 7,100 talents.

Crassus crushed the slave uprising of Spartacus in the Third Servile War, but it was Pompey who, after carrying out mop-up operations, got most of the credit. Crassus was frustrated that Pompey, to whom he otherwise bore no malice, had become known as Magnus while Crassus was unable to attain the same martial renown. In 60 bc, Crassus joined Pompey and the rising political star, Gaius Julius Caesar, in the First Triumvirate. For seven years, the triumvirs practically ran the Senate and the course of the empire. At the conference of Luca in 56 bc, the triumvirs agreed to extend Caesar’s pro-consulship in Gaul for five more years. Pompey and Crassus in turn would share the consulship in 55 bc and thereafter receive pro-consular appointments over Spain and Syria, respectively.

To Crassus, command over Syria seemed the best fortune he had had in his 60 years of life. Great riches were to be found in the East, where the Parthians drew wealth from trade routes and from the agricultural lands of Mesopotamia and Babylonia. Crassus boasted that he would capture the Parthian King Orodes II. He also bragged that he would make Pompey’s campaign in the Third Mithridatic War “seem [like] mere child’s play,” wrote Plutarch. Caesar wrote from Gaul, approving of Crassus’ intentions. Yet many condemned the idea that Rome should wage war on a people with whom they had treaty relations. When Crassus set out for Syria in the late winter or early spring 54 bc, he was confronted by an angry crowd of citizens barring his way out of Rome. Crassus had to call on Pompey to open a way through the mob. At the city gate, the chief agitator, the tribune Aetius, lit a brazier and invoked curses against Crassus. Aetius summoned “strange and dreadful gods,” Plutarch said.

Crassus continued on to Brundisium, from where he set out by ship despite warnings of stormy weather. The rough seas forced Crassus to disembark prematurely and complete his journey overland, through the Roman provinces and protectorates of western Anatolia. Arriving at Antioch, the capital of Roman Syria, Crassus promptly led his army into Mesopotamia. He defeated the paltry troops of satrap Silaces near Ichnae. Wounded in battle, Silaces escaped to alert Orodes. Unfortunately for Orodes, his army depended on feudal levies and would take time to muster.

In the meantime, Crassus took possession of the cities along the Euphrates River and its tributary, the Balissus. Many of the Hellenistic cities, including Nicephorium, switched to the Roman side on their own accord. Settled by colonists after Alexander’s conquests, the Greek cities had no love for their Parthian overlords. At Zenodotia, though, 100 Roman soldiers were treacherously killed after being invited as friends. Crassus punished the city by looting it and selling its population into slavery.

Saluted as imperator by his soldiers, Crassus left 7,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry to garrison strategic strongpoints and returned to Syria for the winter. Crassus’ first campaign had allowed him to secure supply bases and to build local alliances. Crassus was looking forward to having his son join him in the decisive campaign the next summer. Freshly decorated with military honours in Caesar’s Gallic wars, Publius was coming from Gaul. He was bringing with him 1,000 cavalry from allied Gallic tribes. To help finance war expenses, Crassus spent the winter of 54-53 bc extorting money from towns and ransacking the temple of Jerusalem.

In spring 53 bc, King Orodes sent his renowned general Surena into Mesopotamia. Surena was to carry out raids, feel out the Roman garrisons and harass any further offensives by Crassus. The main Parthian army would in the interim be led by Orodes against Armenia. Envoys were sent to Crassus, who had just assembled his army from its winter quarters. The envoys told Crassus that there could be no truce if Rome had declared war on Parthia. Yet if Crassus’ personal ambitions were to blame for the hostilities, then King Orodes might be more forgiving. Crassus retorted that he would give answer when he stood victorious in Seleucia. The envoy pointed to the palm of his hand and replied, “O Crassus, hair will grow there before thou shalt see Seleucia,” wrote Plutarch.

Standing in Crassus’ way would be Surena. Second only to the king, the Parthian nobleman Surena hailed from one of Parthia’s most esteemed families. It was his hereditary privilege to carry out the king’s coronation. Statuesque and handsome, Surena was just under 30 years old. His valor and skill in battle were reckoned unequalled. Surena was first on the walls when he recaptured Seleucia from Orodes’ brother and rival. It was on the open plain, though, where Surena would be able to use the Parthian army to its greatest advantage.

In keeping with their steppe heritage, the Parthians grew to manhood in the saddle. They were attuned to the heat and adept at conserving and finding water. Parthian armies brought with them droves of extra horses so that they had access to fresh mounts. The mainstay of the Parthian army was light archers mounted on Arabian-like steeds. Plutarch claimed that only the Scythians surpassed the Parthians in shooting their bows while riding. The Parthian elite made up the heavy cavalry, the cataphracts, whose horses were bred for weight and strength. The main cataphract weapon was a long pike or spear known by the Greek name as the kontos. The infantry of the Parthians was typically small and of lesser quality, mostly archer serfs from the estates of the lords. Parthians were averse to undertaking offensives in the winter, when the moister air loosened bowstrings. They also avoided cavalry actions at night.

Surena’s force consisted of his personal retainers and levies. Made up entirely of cavalry, it was ill-suited to retaking cities, but it excelled at making the countryside unsafe. Behind their walls, the Roman garrisons in Mesopotamia remained secure, but it was another matter if they ventured outside. Those that brought news to Crassus did so at great peril. They told of a Parthian army so swift that there was no escaping or catching them, of arrows that struck from afar and pierced everything, of armor-clad horsemen who could break through, or hold back, anything. Such talk demoralized the Roman soldiers. They had expected to deal as easily with the Parthians as the late Lucius Lucullus had done with the Armenians and Cappadocians. Now instead of easy plunder, it looked like a real war. Many counselled Crassus to call off the campaign, including one of his chief commanders, the quaestor Caius Cassius Longinus.

His determination unshaken, Crassus set forth for Mesopotamia in late April 53 bc With him were 36,000 fighting men organized into seven legions, each numbering around 4,000 men. The legions were not at their full strength because some of their numbers remained in garrisons in Syria and in Mesopotamia. Crassus also had with him 4,000 cavalry and 4,000 light infantry, including 500 archers. Most were likely Syrian levies, but among them were also the 1,000 Gallic horsemen of his son Publius.

The Roman army had not reached the Euphrates yet when a large body of Armenian cavalry rode up to Crassus’ camp. King Artavasdes of Armenia had come with 6,000 mounted guards, offering to summon another 10,000 cavalry and 30,000 infantry to fight beside the Romans. Artavasdes seemed to have an inkling of the imminent Parthian invasion of his kingdom. Accordingly, he tried to coax Crassus into making a united stand in Armenia, where the hilly country favoured infantry over cavalry. Crassus, though, was set on capturing Seleucia and Ctesiphon. Advancing through Mesopotamia along the Euphrates would also make it easier to supply the army. Furthermore, the Roman garrisons in Mesopotamia awaited relief. Upon hearing his, Artavasdes and his cavalry returned to their lands.

Crassus entered Mesopotamia through Zeugma (Birecik) on the western bank of the Euphrates. During the crossing of the river a thunderstorm blew up. Lightning flashed, and wind and waves caused serious damage to the pontoon bridge. The storm continued to lash the Roman army as it set up its camp on the eastern bank. To make it clear that there would be no retreat, Crassus gave orders for the bridge to be dismantled. Crassus then made the customary purification sacrifice for the army. Accidentally dropping the viscera handed to him by the seer, Crassus smiled and blamed his old age. He assured the distressed bystanders that no weapon shall fall from his hands.

The Roman army headed south along the left bank of the Euphrates. Scouts reported that the land was devoid of men, but there were tracks of a large cavalry force, which had turned about as if pursued. To Crassus this proved the timidness of the Parthians. Around this time, Abgar II, an Arab sheik of the Osroeni and King of Edessa, vis-ited the Roman camp. Abgar had aided Pompey and was known as a friend of Rome. Abgar enticed Crassus with a strategy that would see the Romans turn away from the river and venture eastward into the plain towards the Balissus. The gist of Abgar’s argument was that Surena was nearby, gathering up his loot and was preparing to flee. No one had heard of the king, so it was best to strike before he could gather his forces. Why waste time marching for Seleucia, reasoned Abgar, when the decisive blow could be struck now against Surena?

Heeding Abgar’s advice, Crassus sought out the enemy away from the Euphrates River. The change in plans must have necessitated a transfer of supplies from the river transports to the legions. However, the bulk of the equipment, especially the heavier items such as siege engines, and the majority of the camp followers, would have remained behind. This way Crassus’ army could order a forced march if needed. Presumably, Crassus planned to reconvene with the transports after defeating Surena.

As the Romans marched on, trees and shrubs became scarcer and eventually even grasses disappeared. The merciless sun sapped the spirits of the men. Cassius berated the Arab king for leading Crassus into an “abysmal desert … following a route fit for a nomad robber chief,” wrote Plutarch. Messengers arrived from Artavasdes, bringing the news that Orodes had invaded Armenia and that no Armenian reinforcements could be expected for Crassus. Enraged, Crassus refused to reply. Abgar then rode away from the army, having convinced Crassus that he was leaving in order to manipulate Surena in Crassus’ interests. Abgar had lied; he was spying for Surena.

Several days after leaving the Euphrates, the Romans entered the arid Urfa Harran (Edessa-Carrhae) plain. On the morning of May 6, many of the scouts failed to return. Those that did fearfully reported of brazen enemy cavalry approaching in great numbers. A major engagement appeared imminent. Cassius recommended that the army be deployed in a wide and narrow front with cavalry on the wings. Crassus at first gave orders for Cassius’ plan, then changed his mind and reformed his army into a hollow square. Twelve cohorts protected each side, leaving a score of additional cohorts inside; alongside the baggage, carts and draft animals and remaining followers. Crassus commanded the front and back of the square, with Cassius and Publius on either side, and advanced in tight formation.

Late in the morning, the Roman army reached the Balissus. To the thirsty, sun-burned soldiers, the stream must have been a welcomed sight. The officers thought the army should now make camp and scout out the position and strength of the enemy. After spending the night by the stream, they would then set out fresh in the morning. Urged on by his son, who could not wait to engage the enemy, Crassus thought otherwise. The men were to eat and drink while standing in the ranks and then continue at the same relentless pace as before.

Twenty miles south of Roman-held Carrhae (Harran) and away from the Balissus, the enemy came within sight around noon. Aware that he was vastly outnumbered, Surena sought to confuse and intimidate his opponents. At first the Romans spotted only a small vanguard. Surena had his men cover up their armor and spear points, so that from afar the Parthian army disappeared into the haze of the heat. Having closed in, the Parthian commanders signalled to troops to prepare for battle. The Parthians let out “a deep and terrifying roar,” wrote Plutarch, noting that “a low and dismal tone, a blend of wild beast’s roar and harsh thunder peal,” reverberated from the Parthian ranks, where drummers beat on hollow drums of hide covered in bells.

The Parthians now unveiled their weapons and armor. Their Magianian steel glittered in the sun. The Romans beheld some 10,000 archer light cavalry and 1,000 cataphracts. The horse archers wore their hair long, bunched over their foreheads, in the style of the Scythians, to look taller and more intimidating. Most impressive of all, in their gleaming armor, were the cataphracts. Leading them was Surena, tall and fair, “although his effeminate beauty did not well correspond to his reputation for valour … he was dressed more in the Median fashion, with painted face and parted hair” wrote Plutarch.

The cataphracts dipped their long kontoi and thundered upon the Roman lines, intent on splitting them asunder. However, the legionaries remained steady behind their wall of shields. Horses will only with difficulty be driven to hurl themselves upon a solid wall of infantry. Seeing how deep the Roman ranks were and that they were not about to break in panic, the cataphracts swerved. After them came the rest of the Parthian cavalry, a tumultuous wave of dust, horses, and men, breaking on the rock of the Roman square and flowing around its sides.

Crassus sent forth his light troops, but they were met by a storm of arrows. Shot from powerful composite reflex bows, made of wood, horn, and sinew, whose limbs bent forward when unstrung, the iron arrowheads struck with deadly velocity. The Roman light troops fled back to the legionary lines and nearly threw them into disorder. In their testudo formation, a wall and roof of shields, and further protected by bronze helmets and mailed tunics, the legionaries were nearly impervious to arrows. Arrows stuck quivering into the ground, thudded into wooden shields, or glanced off armor. Still, the sheer number of arrows ensured that a good number hit exposed eyes, faces, throats, hands, and limbs. The arrowheads were barbed and when pulled out ripped apart flesh, sinews and veins.

The Romans hoped that their foes would run out of arrows and then be either forced to fight at close quarters or flee. To prevent such an occurrence, Surena had brought camels carrying loads of ammunition. With no end in sight to the missile barrage, Crassus sent forth Publius with his 1,000 Gallic cavalry, supported by another 300 cavalry, probably Syrians auxiliaries. In addition, 500 foot archers and eight infantry cohorts of roughly 3,200 legionaries would follow the cavalry, to lend support once the enemy was engaged.

When the Parthians took to flight, Publius heartily pressed on in pursuit. The lighter Parthian horsemen appear to have scattered. Publius carried on after the cataphracts. The armored horses of the cataphracts not only were slower than those of the Gauls, but Surena was among them. After the last of the legionaries following Publius had disappeared from Crassus’ sight, the chase came to an end.

At that point, the cataphracts suddenly wheeled around while Parthian light cavalry galloped in from different directions. The Parthian retreat had been a feint. Publius reigned in his cavalry and waited for the infantry to catch up. Bows twanged and arrows swooshed as the Parthians concentrated their fire on Publius’ legionaries. No longer mentioned in the sources, the Roman archers were probably hopelessly outmatched. The horses raised a tremendous cloud of dust, obscuring the vision of both parties.

The Romans were so densely packed that the Parthians could scarcely miss. Riding by at close range, the Parthian arrows even penetrated shields and mail. The Romans fell back upon each other, stumbled, and dropped to the ground transfixed by arrows. Alarmed, Publius sent messengers to his father for urgent reinforcements.

Once again, Publius charged his cavalry at the cataphracts. This time a savage fight ensued. Maneuvering their horses with their knees, the cataphracts gripped their kontoi in a two-handed underarm fashion. The 12-foot-long lances took a terrible toll on the unarmored horses of the Gauls. In contrast, the Parthian steeds were protected with caparisons of iron or bronze scales and head and neck armor. The cataphracts sported bronze or iron helmets and body armor of either scale, mail, or lamellar. They also had neck, arm, and thigh guards and wore mailed gauntlets.

Not all of the cataphracts could afford the whole panoply of protective equipment, though, and those in the rear ranks probably made due with less. The Gauls appear to have fought in their traditional style, making use of round shields, spears, swords, and axes. Given their extensive combat record, a fair number had likely equipped themselves with helmets and mail shirts. Tall and powerful, the Gauls seized the shafts of the kontoi with both hands. Despite the heavy Parthian armor, the Gauls grappled their foes and pushed or pulled them off their horses. Other Gauls leapt off their own steeds and stabbed the horses of their foes in the bellies. Mortally wounded horses lurched and toppled, crushing both their rider and the attacking Gaul.

Heat and thirst combined to weaken the northern tribesmen so that the cataphracts gained the upper hand. Publius was heavily wounded and broke off the engagement. The decimated cavalry rejoined what remained of the infantry and pulled back to a nearby sandy hillock. They secured their horses in the centre at the top of the knoll. The Romans likely kept their wounded here as well, as far out of the range of the arrows as possible. Around the sloping sides of the hillock, the legionaries reformed their shield wall. The legionaries thought that the high ground would give them an advantage; instead, it further exposed the rear ranks, which were higher up on the slope, to the Parthian archers.

Publius could see his legionaries succumbing to the enemy arrows. The end was only a matter of time. Among Publius’ followers were some local Greeks, who knew the lay of the land. They offered to safely guide him out while his men remained behind. Publius answered that no death held such terror as to make him abandon his men. He would not be taken alive. An arrow had pierced his hand, making it difficult for Publius to carry out his final act. Presenting his side to his shield-bearer, Publius ordered him to strike. Most of the other notable Romans with Publius followed his example. When the onslaught of arrows finally abated, there were no longer enough battle-worthy Romans left to resist the pikes of the cataphracts. Only 500 of Publius’ men survived to be taken captive.

With the Parthians having set off after Publius, Crassus was able to retreat up some nearby sloping ground. Most of Publius’ messengers had been killed, but a few barely got through. Hearing of Publius’ plight, Crassus was torn between the life of his son and the survival of his army. He chose his son and ordered the advance when the enemy returned in great numbers. The Parthians hollered war cries, brandished their weapons, and beat their drums. A Parthian herald rode up, holding high a spear with Publius’ head transfixed on it. Surely, this head could not be Crassus’ son, said the herald, for it belonged to one noble and valorous, while Crassus was the basest of cowards.

Crassus rose to the occasion. After all, even after Publius’ losses he retained most of his cavalry and light troops, alongside the bulk of the legions. Riding up and down the ranks, Crassus implored the men to avenge the death of his son. He reminded them that Rome had been in perilous situations in the past and through valour had triumphed all the more gloriously. But Crassus’ oration, usually so effective in the Senate, failed to rouse the confidence of his soldiers. When Crassus called for a war cry, their voices were feeble.

The Parthian mounted archers again drew back their bow strings and sent their arrows screeching at the Roman lines. The cataphracts joined in the attack, steadily advancing then thrusting their long kontoi at the Romans. Designed to slay horses, the kontos easily sundered the links of Roman mail. At times, the long pikes skewered up to two Romans at once. The two pila javelins typically carried by the legionaries appear to have been quickly used up. Their remaining gladius short swords were ineffective against either the archers or against the kontoi. Gripped by fear, the Romans in the front ranks pushed back upon their comrades behind them. The broken Roman formations were then hit hard by missile fire. Although the sources are conflicted, the Romans may have also been set upon by Abgar’s Osroëni, who now appeared and attacked from the rear.

Outfought and outnumbered, Crassus’ light infantry and cavalry were unable to defend the vast perimeter of the legionary lines from missiles and enemy cavalry. The withering Roman ranks were slowly pushed into an ever tightening area. Roman corpses littered the ground. Dying wounded gushed blood and gasped for air. At nightfall the Parthians called off their attack. Quivers were empty, bow strings had snapped, and blades had become blunted. Men and horses were exhausted. A Parthian herald shouted at the Romans; Crassus was to be granted one night to lament his son’s death. The next day, he could either surrender and be brought to their king or be taken to him as a corpse.

The Parthians set up camp nearby. The Romans could hear the boasting of their warriors. An estimated third of the Roman army had been lost. The demoralized legionaries left their dead where they had fallen and even neglected to help their wounded. Although the men blamed Crassus, they wished he would offer them a glimmer of hope. But Crassus was sprawled out on the ground in his tent in utter despair.

With Crassus wallowing in despair, Cassius and a legate named Octavius assembled the officers. It was agree that anyone able to walk would silently depart for Carrhae under cover of the night. A general panic nearly erupted when the cries of the heavily wounded, pleading not to be abandoned, were thought to have alerted the Parthians. The Parthians, though, were loath to pursue in the dark, giving the Romans a head start.

The first contingent to reach Carrhae at midnight consisted of 300 Roman cavalry under the command of Ignatius. He called to the sentinels on the walls, telling them of a great battle between Crassus and the Parthians but little else. Ignatius then rode off to Zeugma, saving his own skin and that of his men. Coponius, the garrison commander of Carrhae, discerned that something bad had happened. He therefore set out at once to find Crassus and Roman survivors and escort them back to Carrhae.

At the break of day, the Parthians slaughtered the 4,000 wounded at the Roman camp. They then set off after the fleeing Romans, killing and capturing many. Other Romans died in their tracks, too weak or wounded to continue. Four cohorts of legate Vargonteius got separated from the main body and lost their way. Caught by the Parthians, Vargonteius’ cohorts made a last stand on a rise of ground. All were slain but 20 men, who tried to force their way through. The Parthians were so impressed by their bravery that they let these soldiers reach Carrhae unmolested.

When Surena learned that Crassus had survived and had reached Carrhae, he demanded that both Crassus and Cassius be handed over in chains. In turn, Surena offered a truce. But the legionaries were not about to give up their commanders. Crassus was hoping that help would arrive from the Armenians, but his men convinced him that their best chance lay in another escape attempt.

Marching west over the open plain to Syria would make the Roman infantry easy pickings for the Parthian horse archers. Accordingly, Crassus decided to strike for Armenia to the north. Only a night’s march away, the plain of Carrhae ascended to what was known as the Sinnaca hill country. This was likely the Tektek Mountains to the northeast, where the rough and steep ground was ill suited for cavalry. Unbeknownst to Crassus, his guide, a certain Andromachus, was conspiring with Surena. Setting out in the dark, Crassus and a small number of men got separated from the main column. Andromachus purposely led Crassus astray into wetlands and irrigation ditches.

Cassius, who was with Crassus, became suspicious and returned to Carrhae during the same night. Like Ignatius, Cassius then made for Syria, taking with him 500 cavalry. Meanwhile, the bulk of the legionaries under Octavius had climbed into the Sinnaca hills before day break. Crassus had found the road to Sinnaca only in the day light. He had almost reached the point where the road led up to Octavius’ position when he was set upon by Parthian cavalry. Crassus and his men made a stand on a nearby knoll.

Looking down from the heights, Octavius could see Crassus and the Parthians one and a half miles down the ridge on a low adjoining hill. Led by Octavius’ example, the legionaries hastened down to aid their commander. Like an unstoppable whirlwind, Octavius’ men swept the Parthians from the low hill. “[They] covered him [Crassus] with their shields,” wrote Plutarch, “boldly declaring that no Parthian missile should smite their imperator until they had all died fighting in his defense.”

Surena realized that the legionaries had a real chance of retreating up the broken ground. Because of this, Surena pulled back his forces and released a number of Roman prisoners. These had been made to overhear that the Parthian king desired friendship. Figuring that the prisoners had told Crassus of his purported sentiments, Surena calmly rode up the slope. Reaching the outskirts of the Roman lines, Surena admitted that he had attacked them against the wishes of his own king. Safe passage would be given if the Romans withdrew and abandoned the land east of the Euphrates. Crassus ended up agreeing to meet Surena, with an equal number of men, halfway between the two armies. Crassus and his entourage, among them Octavius, walked down the slope to where Surena and followers came riding towards them. Surena informed Crassus that King Orodes would accept a truce if it were ratified in writing.

Seeing that Crassus had come on foot in the Roman fashion, Surena presented him with a splendidly caparisoned horse. Crassus mounted the steed, but Parthians ran alongside and hit the horse, urging it to bolt. Octavius seized the bridle to get the animal under control and was joined by the other Romans who crowded in to protect Crassus. A scuffle ensued, becoming more violent. Octavius drew his sword and slew one of the Parthians, but then was cut down from behind. Crassus was also killed, either by the enemy or by his own men trying to prevent his capture. The Romans fighting around Crassus were slain as well. Crassus’ corpse was decapitated and his right hand also was cut off. The Parthians allegedly later poured gold down Crassus’ mouth to mock his greed for wealth.

Surena announced to the Romans on the hill that Crassus had met his just deserts, but that they could surrender without fear of being killed. Some did and were taken into captivity; others fled during the night. Although a few reached friendly territory, most were hunted down by Arabs. Approximately 20,000 Romans perished in the whole campaign and another 10,000 were captured, according to Plutarch. Some of the latter settled in northeastern Parthia at the oasis of Margiana (Merv).

Surena sent the hand and head of Crassus to King Orodes in Armenia. At the same time, Surena sent false word to Seleucia that he was bringing Crassus back alive. Upon Surena’s arrival at Seleucia, a captive who resembled Crassus was forced to act the part and dress in a woman’s royal robe for a mock procession. Behind Crassus followed captured lictors to whose axes were fastened severed Roman heads. Musicians sang songs of Crassus’ effeminacy and cowardice.

Meanwhile, Orodes had reached a settlement with Artavasdes and sealed it with the marriage of Orodes’ son to Artavasdes’ sister. The two kings were enjoying a festive banquet when, in the midst of applause for an actor, Surena’s messengers arrived and cast forth Crassus’ head. The Parthians hollered in joy as the actor picked up the head, singing and gesturing as if the head was singing the verses of a female character in the tragedy. With such ridicule, Crassus’ tale came to an end.

Surena recaptured the Roman-held towns between the Balissus and the Euphrates, but his achievements did not gain him Orodes’ favor. Orodes became jealous of Surena and wound up putting his greatest general and potential rival to death. Fortune then turned against Orodes, whose body was ravished by disease. A Parthian invasion of Syria that he conducted in 51 bc ended in failure. Thwarted by the walls of Antioch, the Parthians were lured into an ambush by Cassius, the veteran of Carrhae. In 38 bc another Parthian invasion resulted in the death of Orodes’ son Pacorus. The Parthians suffered defeat after failing in their assault on a heavily fortified Roman camp. Orodes’ other son Phraates then turned against him, first trying to poison Orodes and then, when this failed, strangling him.

At Rome, news of the disaster at Carrhae was shrugged off as the failure of Crassus’ own ambitions and not as a national defeat. Crassus’ death nevertheless proved disastrous for Roman politics. His removal as a counterpoise to the other two triumvirs unravelled the triumvirate. Caesar and Pompey turned against each other, unleashing another civil war. Caesar emerged the victor and planned to invade Parthia but was assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 bc Cassius was one of Caesar’s assassins.

Carrhae revealed the tactical shortcomings of an army dominated by heavy infantry against one of mobile horse archers. The Parthians cavalry could retreat whenever it wanted, while the opposite was true for the Roman infantry. The Roman army addressed its limitations by adding sufficient auxiliary cavalry, slingers and archers. The aura of Parthian invincibility that had grown up after Carrhae was eventually broken. Subsequent defeats suffered by the Parthians caused a shift in their strategy from large battles to skirmishes and raids against supply lines. The Roman standards captured at Carrhae were returned to Rome during the reign of Emperor Augustus.

Emperor Trajan had nearly conquered Parthia when it slipped out of his grasp just before his death. In the Roman-Parthian War during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the Parthians initially wiped out a legion, but Rome countered by sacking Seleucia and Ctesiphon. The greatest obstacle to a Roman conquest of Parthia turned out to be not its horse archers but the massive logistics required for supply lines and garrisons. Moreover, climate and disease also sapped the strength of the Roman soldiers. Weakened by their wars with Rome, the Parthians were overthrown by the Persian Sassanids early in the 3rd century.

Much of the credit for the Parthian victory at Carrhae must be given to Surena. Unfazed by the size of the Roman army, Surena skilfully used a combination of horse archers and heavy cavalry to wear the Romans down and then finish them off. Surena also made use of superior intelligence, being aided by informers that had gained Crassus’ confidence. They successfully misled the Romans into situations where the Parthians had the tactical advantage. The result was that at Carrhae, ancient Rome suffered one of the most disastrous defeats in its entire history.