By Pedro Garcia

On the night of August 4, 1864, in the cabin of his flagship the USS Hartford, Admiral Farragut read his Bible, arriving at ultimate assurance that God was on his side. There was a knock on his door.

“Admiral,” asked an officer, “won’t you give the sailors a glass of grog in the morning—not enough to get them drunk—but just enough to make them fight well?”

“No Sir!! I never found that I needed rum to enable me to do my duty. I will order two good cups of coffee to each man at 2 am, and at 8 am I will pipe all hands to breakfast in Mobile Bay.”

Much farther north and east, in Richmond, Va., Confederate States President Davis also resorted to prayer and wired the defenders of the environs of Mobile, Ala., “May our Heavenly Father shield and direct you, so as to divert the threatened disaster.”

In the city of Mobile, newspapers confidently predicted that Farragut could fire until the end of the war, but the forts guarding the harbor would still stand. The men inside Fort Morgan bragged that because they could hit a bobbing barrel at a thousand yards, they could knock the Hartford out of the water.

Mobile was by far the most important Gulf of Mexico port used by blockade-runners, New Orleans having fallen to Northern forces in April 1862. At first, running the blockade had been easy. Mobile was infused by a giddy and gay atmosphere in those days: Young men in flashy uniforms were leaving for army camps accompanied by colorful celebrations and grandiose oratory and levity; schoolboys toting wooden guns drilled in the streets; and anxious businessmen of Northern loyalty quietly left town. Southerners could afford to joke about the Union blockade in 1861: Equipped with 50 warships, more or less, the U.S. Navy had to cover 3,550 miles of Southern coastline, 189 harbors or inlets, and nine major seaports.

Odds of Capture by the Blockade Were One in Three

But by the summer of 1864 Southerners found nothing humorous about the blockade—almost 500 warships patrolled the coastline and rivers. Eluding capture was not an easy task for runners; the odds of capture—1 in 10 in 1861—-were now 1 in 3. Yet, Mobile was even more difficult to blockade than the Carolina ports. The distance from Pensacola to the Rio Grande is about 600 miles, not counting the Mississippi River delta. Behind this coast is an intricate network of inland waterways in which shallow-draft craft could move safely to find an exit or inlet not covered by blockaders.

The Federal warships patrolling outside Mobile Bay were part of Farragut’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron, and duty was routinely mundane and monotonous, punctuated by moments of high drama. Aboard each ship, a deck officer posted aloft in the boson chair scanned the dark horizon, moonless nights being favored by blockade-runners, straining to spot the silhouette of a runner or a distant plume of smoke. If a runner was sighted, a signal rocket would streak through the night, sending seamen to their battle stations, and with steam up, the chase was on. Firing rocket after rocket to mark the runner’s path, the blockaders would pursue their quarry. Hurriedly shoveling pitch pine and rosin chunks into the ship’s furnace, the ship’s firemen stoked a hotter fire to build speed. Aboard the harried blockade-runner, firemen would fuel the ship’s furnace with sides of bacon or turpentine-soaked cotton to gain enough speed to outdistance the enemy. Narrow escapes were common, but when capture seemed imminent, a captain would heave to and surrender. More often, he would turn toward shore and try to beach his vessel in the breakers, hoping his cargo could be salvaged later.

Cornered Captains Beached Their Own Ships

Now and again a lighter moment highlighted the chase. In October 1862, the Caroline was captured after a six-hour chase off Mobile. When brought aboard the Hartford, her captain protested vehemently to Farragut that he was not headed for Mobile but for Matamoros, Mexico, as his clearance papers revealed. To this fantastic claim the old admiral replied, “I do not take you for running the blockade, but for your damn poor navigation. Any man bound for Matamoros from Havana and coming within 12 miles of Mobile Point has no business to have a steamer.”

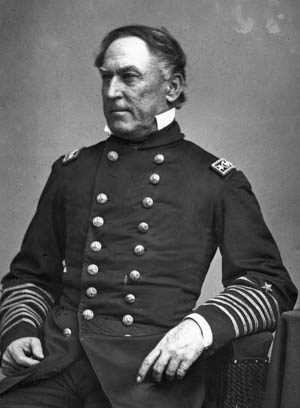

When Farragut was ordered to capture New Orleans in January 1862, the order from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles specifically mentioned the capture of Mobile as a follow-up measure. Accordingly, the Union occupation of the Crescent City was barely days old when Farragut began planning his operation at Mobile Bay. But President Lincoln and Welles postponed this event until the opening of the Mississippi had been completed, and sent Farragut upriver to cooperate with Flag Officer Charles H. Davis. Farragut hated the river—it was no place for his sloops of war—but there he stayed until Port Hudson and Vicksburg surrendered in July 1863. All but broken in health from the arduous service in the malaria-ridden lower Mississippi, he took a leave of absence.

By the summer of 1864, Northerners and Southerners alike believed that action was long overdue at Mobile. As David Dixon Porter, a Union naval officer, once put it, “Mobile is so ripe now, that it would fall to us like a mellow pear.” If Rear Adm. Farragut had had his way, it would have been closed off from the sea in 1862. Writing in 1887, an officer who served on board Farragut’s flagship said, “It is easy to see now the wisdom of his plan. Had the operation against Mobile been undertaken promptly, as he desired, the entrance into the bay would have been effected with much less cost of men and materials, Mobile would have been captured a year earlier than it was, and the Union cause would have been spared the disaster of the Red River campaign of 1864. At this late date it is but justice to admit the truth.”

Grant’s Proposed Attack on Mobile Was Repeatedly Denied

In addition, shortly after his capture of Vicksburg, Ulysses S. Grant proposed that he attack Mobile with the help of the Navy. He thought it would be an ideal base for operating in the deep South. The request was refused, not once but three times. After his successful operations at Chattanooga, he renewed his proposal and once again it was denied. General Nathaniel Banks at New Orleans also proposed that he attack Mobile, but he was ordered into Texas on what would turn out to be the ill-fated Red River operation.

Then in January 1864, a recuperated and rejuvenated Farragut resumed command, and his first act was to make a personal reconnaissance of Mobile. Taking charge of a gunboat in his fleet, he ordered the vessel in close, “where I could count the guns and the men who stood by them.”

Unlike New Orleans, Mobile had prepared well for the onslaughts of the Union fleet. This, however, was due less to Rebel tenacity than to the Union’s attention to other objectives. Indeed, viewed from afar, a heavy mist of ripeness hovers over the opening days of summer 1864.

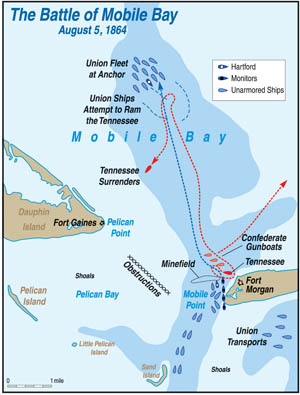

Yet, during the long months that the Confederates had been left in comparatively peaceful possession of Mobile, an elaborate system of fortifications had been created for guarding the entrances to the broad but shallow sandy shoals of the bay. The city itself was at the head of Mobile Bay, about 20 miles from the ocean. On the tip of Mobile Point was erected the pentagonal Fort Morgan, garrisoned by 700 men and 79 guns, which easily commanded the shipping channel, half a mile wide and 21 feet deep. About three miles to the westward rose Dauphin Island, on the eastern point of which was Fort Gaines with 26 guns, which commanded Pelican Channel, actually a shallows projecting two miles toward the shipping channel.

“If I Had One Ironclad I Could Destroy Their Whole Force”

To strengthen and improve the defenses, the Confederates had thrown up obstructions, extending in the shallows from Fort Gaines eastward toward Fort Morgan. Off the obstructions, in deeper water, a row of black buoys marked three staggered lines of mines, which were then called torpedoes. They reached directly across the main channel to within 500 yards of Mobile Point, so that passing ships, in order to skirt the minefield, had to pass directly under the guns of Fort Morgan. Farragut well understood the full significance of the ominous black buoys, but he was confident that the submersibles, encrusted with barnacles, their powder damp, were waterlogged and powerless. He also believed a good many had drifted from their moorings. But the danger could not be ignored or taken lightly, and with that in mind Farragut sent boat crews out at night to find the buoys, then fumble around until they located the mines anchored a few feet under the water. When found, they would be either sunk or removed.

Formidable as it all looked, the old admiral was not impressed. “I am satisfied,” he wrote to Secretary Welles, “that if I had one ironclad at this time I could destroy their whole force in the bay,” and with 5,000 cooperating soldiers from the army, “reduce the forts at my leisure.” The Tennessee native, who was perhaps the best naval officer on either side, based his superb tactics on an analysis of his shortcomings as well as those of his opponent. This 54-year veteran of the Navy understood the limitations of land fortifications, and both on the Mississippi River and at Mobile Bay he used this tactical understanding flawlessly. It is revealing that in all of his communications with Secretary Welles during this period, Farragut’s first consideration was the condition of his opponents, and even more revealing that he was willing to act upon his perception of their weaknesses.

All Confederate Hope was Pinned on the Famed Ironclad Tennessee

This was another indication of Farragut’s best-case or optimistic approach to the conduct of war. It was easy to see an opponent’s strengths, but Farragut took a step beyond and tried to comprehend his opponent’s problems and limitations. He was also very aware that, about 130 miles north of Mobile—at Selma—the Confederates had built one of their largest naval stations. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory, intent that Mobile not be lost and responding to cries of alarm from the governor of Alabama, contracted for two floating batteries in May 1862, the Huntsville and the Tuscaloosa. Originally planned as ironclads, their engines proved inadequate. Barely able to stem the weak current, the ships clearly could not confront the enemy in open battle, but they might work as floating batteries. Moreover, in the fall of 1862 other contracts had been closed, one of which was a powerful screw ship that would become one of the most powerful and famed Confederate ironclads, the Tennessee. All hope was staked on her.

Rear Admiral and historian Alfred Thayer Mahan called the Tennessee “the most powerful ironclad built from the keel up by the Confederacy.” She was probably the most potent craft that sailed from a Confederate navy yard during the war. Her displacement was 1,273 tons; she was 209 feet long with a 48-foot beam, and was fitted with a casemate 79 feet long. The internal structure of the casemate was of yellow pine 18.5 inches thick, augmented by 4 inches of oak. This was covered by 5 inches of iron plate, increasing to 6 inches forward. Her outer decks were armored with 2-inch sheet iron. The lower reaches of the casemate descended under the waterline and formed a solid angle that would make it very difficult to ram the ship. She carried a battery of six Brooke rifles; two of 7.5 inches forward and astern, pivoted so that they could be fired either from a porthole in front or from two ports on the sides. She carried the other four, of 6 inches, in broadsides. Her shallow draft would allow her to find refuge in the broad expanses of 14-foot water that was not accessible to Farragut’s heavy warships.

Nevertheless, the Tennessee had some serious flaws that would impair her at critical times. First, she was very slow because her engines, recovered from a river steamer, had been patched together and adapted by a system of connecting gears to give her screw propulsion, resulting in a great dissipation of power. Even though in her engine trials she had logged 8 knots, when fully loaded she could barely make 6. Second, her port shutters, 5 inches thick, were hinged high; under enemy fire they might fall and obstruct the portholes. Last and most serious, through some unbelievable oversight, the tiller chains passed over the deck astern and were therefore fully exposed to enemy fire. As her captain said, “We were compelled to take the consequences of the defect, which proved to be disastrous.”

The South Desperately Cannibalized Machines for Makeshift Repairs

The South had little to work with: Old locomotive boilers were cut and pressed together in new shapes to serve new purposes while once-careful mechanics looked the other way in embarrassment at their tired handiwork; and fatigued machinery of memorable steamers was dismembered and made to serve purposes its designers could not have foreseen. Furthermore, the Tennessee’s advantage of shallow draft could be checkmated if Farragut had monitors of similar or even lighter draft.

After the loss of New Orleans, the South’s hero of Hampton Roads, Admiral Franklin Buchanan, had been ordered to Selma to supervise the building of the Tennessee and the creation of a fleet that would break the Federal blockade. Mallory originally had sent his most aggressive senior officer to Mobile, not only to raise the blockade off that city, but also to cooperate in a combined effort to regain New Orleans and the lower Mississippi. Therefore, his building operations were essentially offensive in motive, but were defensive in fact. For “Ol’ Buck” Buchanan, the battle to come meant victory or defeat for the entire Southern navy. The Mississippi was lost, for which Galveston and other Texas ports were useless; Charleston and Savannah were bottled up and would stay that way.

During the night of May 17, Buchanan succeeded in getting the Tennessee over Dog River bar below Mobile and into the lower bay. His plan was to run through the blockade and capture nearby Fort Pickens and Pensacola, Fla. But the ironclad ran hard aground in the lower bay after crossing the sandbar, and was discovered by blockaders the next morning. Anxious days passed, but neither belligerent made a move. Buchanan seemed overawed by the Union fleet and, believing an attack was imminent, dropped all pretense of offensive action, preparing for the expected blow. Farragut fully believed that Buchanan, who had been refloated at high tide, was waiting for a dark night and smooth sea to renew his sortie.

”The Trial Must Be Made. So Goes The World.”

“No doubt is felt of his success. Coming on the heels of the rebel successes on the Red River, the public mind is in such a state of excitement,” Farragut wrote to Welles. It was believed that if the ram destroyed the blockade off Mobile in the wake of General Bank’s failure on the Red River, New Orleans would panic and might be lost to the Union. Thus a naval stalemate developed off Mobile that was to last for the next month and a half. In addition to the Tennessee, Buchanan had three wooden gunboats somewhat comparable to Farragut’s lighter ships. They were the Morgan, Gaines, and Selma, with a total of 22 guns, including four very effective Brooke rifles, yet they had been converted from river steamers, and their light construction made them poorly suited for the rigors of battle. The greatest faith was in the Tennessee. She was a very powerful ironclad—but her most serious deficiency was that she was alone. The South held absurdly high hopes for her. Buchanan wrote to a friend, “Everybody has taken it into their heads that one ship can whip a dozen, and if the trial is not made, we who are in her are damned for life, consequently the trial must be made. So goes the world.”

Tennessee was a formidable obstacle, which Farragut would find across his path on the day he determined to attack. To his son, the admiral wrote, “Buchanan has a vessel which he says is superior to the Merrimac, with which he intends to attack us.… So we are to have no child’s play.”

By the spring of 1864, the Yankees bossed the Mississippi River system, West Virginia, Tennessee, Virginia north of the Rapidan River, parts of Louisiana, and most of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. But the bulk of the Confederacy was still intact. Rebel arms controlled the Shenandoah Valley, and two powerful armies—Lee’s in Virginia and Joe Johnston’s in Georgia—remained defiant. Grant with an army twice the size of Lee’s advanced toward Richmond, but was repulsed with bloody losses in May at the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, and in June at Cold Harbor. General Sherman and his “bummers,” 80,000 strong, pushed off from Chattanooga, plunging into the Deep South toward Atlanta. With Atlanta in sight, Sherman wanted to prevent the Confederate troops in southern Alabama from moving to Johnston’s aid.

Although not yet prepared to roll the dice, Farragut was at least ready to shake them and, eager to help, he decided he could assist Sherman by pretending to force an entrance into Mobile Bay. On February 13, he sent six mortars to the west of Dauphin Island to attack the small, weak, and unfinished Fort Powell. The mortars, supported by four gunboats, put up a fierce display. Confederate General Dabney Maury, military commander of the district, bought the ruse, panicked, and asked Richmond for more troops. Thus, any intention of siphoning off troops from Mobile to defend against Sherman was dropped, and Farragut had accomplished something at the cost of a few mortar shells.

2,100 Tons, 225 Feet Long, Heavily Armored, and Capable of Firing 430-Pound Projectiles

Farragut, who up to this time had been scornful of ironclads and now faced an imminent meeting with one, had a touch of “ram fever.” His reports to Secretary Welles of the appearance of the Tennessee in the lower bay produced prompt action. Welles ordered the ironclad Manhattan to leave the naval yard at Norfolk and report to Farragut; soon a second ironclad, the Tecumseh, received the same orders. Furthermore, Admiral David Porter was ordered to send Farragut two light-draft ironclads from the Mississippi Squadron—the Winnebago and Chickasaw.

All were formidable vessels of the Monitor class, but much more powerful than the famed prototype. The Manhattan and Tecumseh displaced 2,100 tons, were 225 feet long, and had much stronger armor than had been used earlier. Their most important asset was their ordnance—each had two gigantic 15-inch Dahlgrens—the same caliber used by the 40,000-ton battleships of World War II—capable of firing projectiles weighing more than 430 pounds. The twin-turreted, quadruple-screwed river monitors, although built to operate in shallow inland waters, would prove themselves extremely efficient. They were 229 feet long, displaced 1,300 tons, and held four 11-inch Dahlgrens.

The arrival of the first monitor was the signal for Farragut to prepare his ships in earnest for the attack. The old admiral must have sensed that fortune had brought the well-nigh impossible of three months ago within the reach of his courageous grasp, and so convinced was he of the ripeness of the moment, he refused to procrastinate. To increase pressure on Joe Johnston’s army, early in June Sherman wired General Edward Canby, who had relieved Banks after his dismal Red River campaign, and asked him to raise a ruckus with Farragut at Mobile. On June 17 General Canby conferred with Farragut, and on July 3 sent him General Gordon Granger with 2,400 troops, to land in the rear and invest Fort Gaines. They were all that could be spared at the time, because General Canby had been ordered to send reinforcements to the Army of the Potomac, which would eventually operate in the Shenandoah Valley under General Phil Sheridan.

General Page, who commanded at Fort Morgan, was convinced his firepower was inadequate, although General Maury was certain that the forts, obstructions, and the Tennessee would obliterate Farragut’s squadron. Farragut was obviously expecting the hottest contest of his career. “I know Buchanan and Page, both officers of known merit in the old navy, will do all in their power to destroy us, and we will reciprocate the compliment. I hope to give them a fair fight, if I once get inside,” he wrote to his son.

“They Will Do All in Their Power to Destroy Us, and We Will Reciprocate the Compliment”

Fort Morgan, built in 1818 as part of the coastal defense program begun after the disastrous British landing in the War of 1812, was obsolete in 1864 and unable to withstand the fire of powerful rifled guns. However, the weakest aspect of the fort was the Mobile Point peninsula. Low and sandy, it presented no obstacle to the landing of troops seeking to take Fort Morgan from the rear. Moreover, despite the fear the torpedoes inspired, they were the weakest point of the Mobile Bay defenses. According to the Confederate commander of the Corps of Engineers, the Prussian Victor von Sheliha, they were anchored on shifting sands and unstable gravel. Furthermore, the Confederates had also been obliged to leave a 500-yard gap between Fort Morgan and the torpedo field to allow passage of blockade-runners.

Admiral Mahan later correctly observed that if the Confederates had laid electrical torpedoes, they would have been able to close the whole bay and channel. Because they did not they were limited to obstructing the western part of the channel by a triple line of contact torpedoes that they hoped would force enemy ships under Fort Morgan’s guns. Had they been used, electrical torpedoes could have been connected to Fort

Morgan by cable for turning on and off depending on what sort of ship was approaching. Instead, contact torpedoes, which can become ineffective from prolonged immersion, were laid in three lines along the western part of the channel and were marked with black buoys. To avoid this threat ships entering the bay were forced to pass under the guns of Fort Morgan.

Farragut’s fleet prepared for action. They stowed superfluous spars below, rigged splinter nets on the starboard sides, barricaded the helms with sails and hammocks, heaved hempen fenders over the inboard sides, and spread chains and sandbags around the deck machinery. To prevent disabled craft from jamming up the battle line, the smaller gunboats were lashed side by side with chains and were to run up to the forts in pairs, just as Farragut had done at New Orleans and Port Hudson. The spearhead of the attack was to be the four monitors and was to proceed in advance off the starboard bow of the main column of seven pairs of wooden ships carrying a broadside of 75 guns. The lead monitor, Tecumseh, had orders to hug Mobile Point and lead them to the right of the most eastern buoy, which marked the minefield. Although the column of wooden ships was not to pass at such close range to Fort Morgan, it also was to clear the eastern end of the ominous markers.

Farragut made his plans and the Confederates made theirs. On July 28, the Tennessee cruised the bay, majestically, calmly, engaged in target practice; and from the deck of the Hartford, Farragut watched 400 miserably clad, half-drilled cadets from Mobile, boys 14 to 18, arrive at Fort Gaines to reinforce the garrison. On the western end of Dauphin Island, Granger’s troops, on August 3, landing with difficulty in the heavy surf, lugged six 3-inch Rodman rifles seven miles through sand and planted them 1,200 yards from Fort Gaines. Trenches were shoveled. Watching them, Farragut wrote: “I can lose no more days. I must go in day after tomorrow morning, or a little later. It is a bad time, but when you do not take fortune at her offer, you must take her as you can find her.”

An Omen of Victory?

Farragut fretted all day long on August 4, waiting for sight of the Tecumseh, which had not arrived from Pensacola. He slept poorly. Of the grave ponderings that may have troubled his mind, or the dreams that visited his sleep, history cannot say. It rained hard about sundown, cleared, and under a half-moon and a high black sky salted with shimmering stars, a comet flashed across the sky. Even the most hard-bitten salt, filled with the superstitions of the sea, had to admit that the heavens were offering an omen of victory. For whom, Farragut or Buchanan, was an issue that would be decided presently.

About 3 am, Farragut awoke, dressed, and breakfasted with his chief of staff. As he sipped hot tea, he sent his steward to ascertain the direction of the wind and the condition of the weather. When informed that there was a light wind from the southwest and the sea was all but a dead calm, he put his fork down and quietly declared, “Well, Drayton, we might as well get under way.”

Aboard the Tennessee, conditions were horrendous. The officers and crew had lived atrociously since crossing into the lower bay. Rains came nearly every day and with them, said Surgeon Daniel Conrad, “the terrible moist, hot atmosphere, simulating that oppressiveness which precedes a tornado.” Sleep was impossible. “From the want of properly cooked food, and the continuous wetting of decks at night, the officers and men were rendered desperate.” All hands looked forward to the impending battle, whatever the outcome, “with a positive feeling of relief.”

“Like Prize Fighters Ready for the Ring”

For weeks Conrad had watched the Federal ships multiply outside the bay. Stripped for action, they “appeared like prize fighters ready for the ring.” At daybreak on August 5, the doctor and his admiral were roused by the quartermaster and informed that the “enemy’s fleet is under way.” They climbed to the hurricane deck, Buchanan painfully limping from wounds suffered at Hampton Roads. Upon seeing Farragut making for the main channel, Buchanan nodded and turned to the skipper. “Get under way, Mr. Johnston,” he said. “Head for the leading vessel of the enemy and fight each one as they pass us.” If there was valor and superlative fighting mettle to be shown, these sons of the Confederacy would show it. If David Farragut wanted the title of hero, he would have to earn it.

With a bright sun rising in a cloudless sky, August 5 promised to be a typical summer’s day. In fact, it had, indeed, produced ideal conditions for Farragut. The southwesterly wind would carry the smoke of the battle into the eyes of the gunners at Fort Morgan, and there was an early morning flood tide that would carry damaged ships past the fort into the bay. As the fleet swung into motion, a solitary Yankee gun signaled Granger’s troops on Dauphin Island to commence firing on Fort Gaines. Infantrymen, sweating and blackened, threw off their clothing, cursed the boiling sun, and poured shot and shell into the Rebel earthwork. The curtain was now raised on this drama.

The Dramatic Naval Battle Begins

At 6:22 the Tecumseh, which had arrived at 2 am, leading the monitor line, opened the battle, firing a ranging shot from each of her monster 15-inch guns. Farragut signaled for closer order, each pair of vessels a few yards apart, echeloned a bit to starboard and, helped by the flood tide, swept majestically onward. At 7:06, range half a mile, Fort Morgan opened fire, immediately answered by the leading Brooklyn with her forward Parrot rifles. “It is a curious sight to catch a single shot from so heavy a piece of ordnance,” observed a surgeon on the USS Lackawanna, recalling the impression left from the view of the first shell from Fort Morgan. “First you see a puff of white smoke upon the distant ramparts, and then you see the shot coming, looking exactly as if some gigantic hand had thrown in play a ball toward you. By the time it is half way, you get the boom of the report, and then the howl of the missile, which apparently grows so rapidly in size that every green hand on board who can see it is certain that it will hit him between the eyes. Then, as it goes past with a shriek like a thousand devils, the inclination to do reverence is so strong that it is impossible to resist it.”

“Soon after this,” Farragut wrote, “the action became lively.”

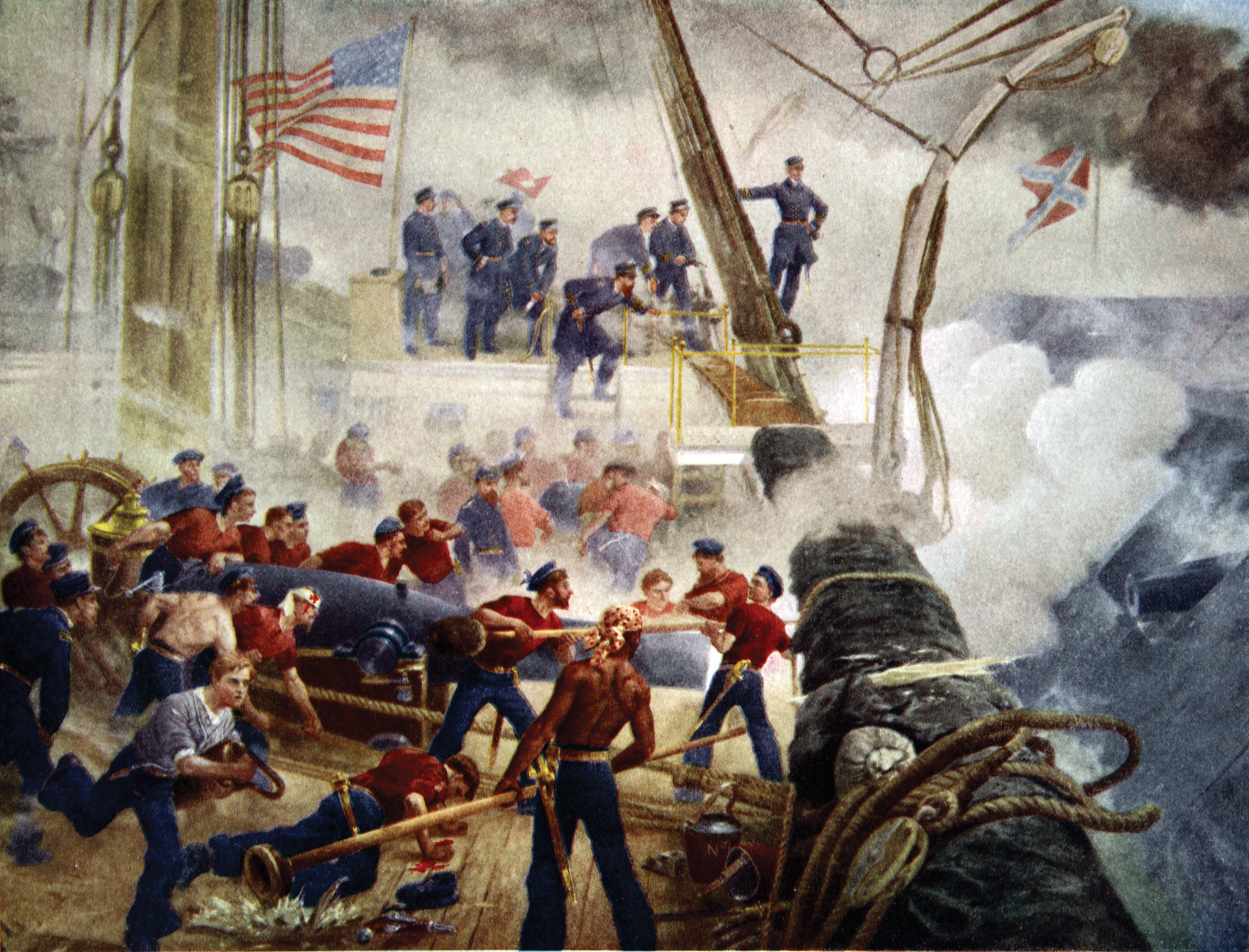

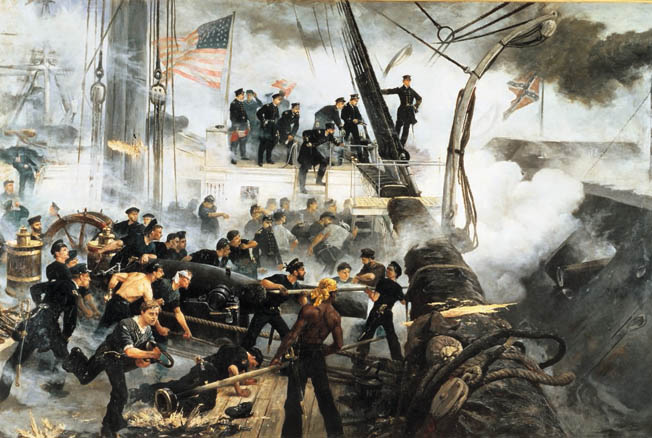

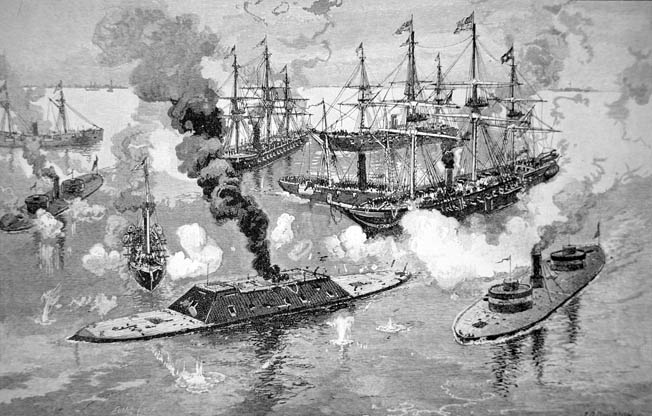

As the monitor division approached Fort Morgan, the Tennesseeand the gunboats Selma, Gaines, and Morgan steamed from under the shelter side of Mobile Point and took position across the main channel, but behind the minefield. Buchanan had executed the classic naval maneuver of crossing Farragut’s “T.” In minutes, a galling and murderous raking fire was loosed down the long axis of the Federal line. Meanwhile, the column of wooden ships was coming up on the port quarter of the monitor division, sailing into positions where they belched a stunning barrage upon Fort Morgan—Confederate fire slackened appreciably. Farragut, in order to discern the course of the battle in the resulting pall of smoke, climbed high into the main rigging, and as the smoke grew heavier ascended rung by rung to just under the main top. Captain Drayton, who remembered that the admiral suffered mildly from vertigo, and fearing that he might have a bad fall if wounded, sent a quartermaster aloft to pass a line around him and secure him to the rigging.

Thus originated the story that Farragut went into the battle “lashed to the mast.” This much publicized incident was merely a safety precaution while the admiral was in an exposed position to get a better view of what was going on. The pilot was also in the main rigging for the same reason, and he had a voice tube to the captain on deck. Farragut had hardly gained this position when he saw the impetuous Tecumseh among the line of buoys that marked the minefield.

Craven Saves the Heaviest Charges for the Tennessee

Captain Tunis Craven of the Tecumseh looked through the heavy grilled port of his tiny smoke-filled conning tower, and is alleged to have decided that there was not room for him to pass to the right, or eastward, of the designated buoy. He clanged four bells to the engine room and tried to pass the rows at full speed. It seems that, confident of the vessel’s invulnerability and the destructive power of her enormous 15-inch Dahlgrens, he was intent on being the first to get at the Tennessee. It is definitely known that after he fired the one round from each of his guns at the pestiferous Fort Morgan, he immediately reloaded them with the maximum possible charges of powder, holding them for the Tennessee.

As Catesby ap R Jones had recommended, artillerists at Fort Morgan fired calmly, accurately, and below the waterline at the Union ironclads. He had been a lieutenant on board the CSS Virginia and had commanded the ram after Buchanan fell. Now as head of the Selma Cannon Foundry, he had supplied the fort with a few of the revolutionary Brooke rifles, and had written to General Page with his well-considered views.

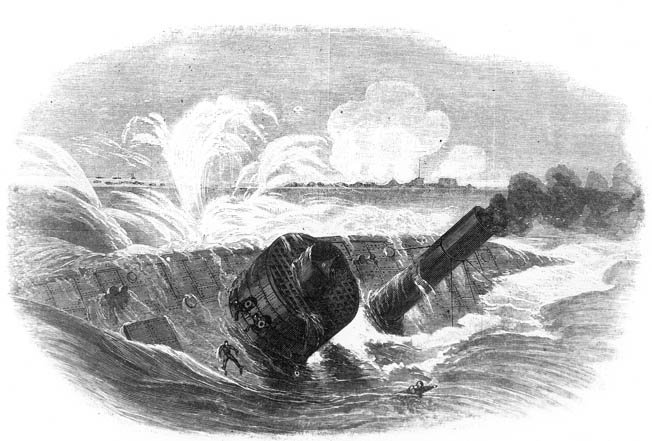

At 7:30 the Tecumseh, abreast of the fort, was hit by at least two steel-cored armor-piercing projectiles. It veered off course, steaming farther into the torpedo field. Suddenly there was a fearful explosion and instantly a towering geyser of water shot from the bow. Her hull smashed, the ironclad lurched and heeled to port, “as from an earthquake shock.” For one brief, coruscating moment, sinking by the bow, her propeller could be seen racing madly in the air, then she foundered, dragging into the chasm her captain and 92 men.

“Immediately,” said Surgeon Conrad of the Tennessee, “immense bubbles of steam, as large as cauldrons, rose to the surface of the water … only eight human beings could be seen in the turmoil.”

John Collins, the Tecumseh’s pilot, was one of them. He and Captain Craven stood at the ladder of the turret roof. “After you, pilot,” said the captain. “There was nothing after me,” Collins said later. “When I reached the utmost rung of the ladder, the vessel seemed to drop from under me.” Some men leaped from the side and swam away from the suction. Everywhere, for a few moments, an eerie silence took hold as men stared. At Fort Morgan, General Page ordered his gunners to hold their fire against the boats that were rescuing survivors.

Sailors Stared Through Smoke in the Eerie Silence

While the Tecumseh was rushing to her doom, she was involving the leading screw sloop Brooklyn in a situation that threatened disaster for the whole fleet. One of her lookouts reported shoal water to port, in the direction of the minefield, a stretch of water that was out of bounds. Then “a row of suspicious looking buoys directly under our bow” was spotted—empty shell boxes from Fort Morgan. Unsure of whether to stop or press on, Captain James Alden of the Brooklyn backed engines to clear the hazard, threatening collision along the entire battle line. In any case, stalled in the Tecumseh’s mess, Brooklyn made the whole fleet, brought into a confused huddle in the narrow channel, a stationary point-blank target. The Rebel gunners in Fort Morgan, recently driven to shelter by the fleet’s broadsides, returned to their pieces, unleashing a wilting counterfire that cut down scores of sailors. Furthermore, from such a disordered formation, as compressing the van hindmost onto center, the fleet could not return an effective counterfire, or even withdraw without confusion and loss.

At this critical moment, a naval officer observed, “The batteries of our ships were almost silent, while the whole of Mobile Point was a living line of flame.” Lieutenant Kinney of the Hartford remembered, “The sight was sickening beyond the power of words to portray. Shot after shot came through the side, mowing down the men, deluging the decks with blood, and scattering mangled fragments of humanity.” From ahead came the relentless raking fire of the Confederate squadron, against which Farragut could not reply.

“The Sight was Sickening Beyond the Power of Words to Portray”

The battle was turning on the edge of a razor. The slightest flinching by Farragut was critical. A great commander by nature, every bit as bold and intelligent as the transcendent Nelson, Farragut’s qualities of leadership carried the day. From his lofty position just below the main top, he asked the pilot if there was sufficient depth of water for Hartford to pass to the port of Brooklyn. Receiving an affirmative, with propeller churning ahead, the flagship pivoted on her heel and shot past the confused Brooklyn. There are several versions of just what Farragut said and did next. It is alleged that as the Hartford passed the Brooklyn, someone aboard Brooklyn cried out a warning of torpedoes to the admiral, in answer to which he shouted the famous words, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” Most Farragut biographers and historians of the battle give full credence to the episode and his words, yet they were attributed to him 14 years after the event. That an oral order from his position high in the rigging could be heard on deck through the din of battle is doubtful. What is certain is that by order, gesture, or in some form, the spirit of that command was transmitted, and the Hartford lay a course straight for the minefield.

A less heroic and probably more accurate account was presented by Lieutenant Kinney of the 13th Connecticut Infantry, who at that moment was serving in one of Hartford’s tops. He was one of a detachment of army signalmen distributed among the fleet in order to facilitate cooperation with Granger’s land forces. He declared that, “as a matter of fact, there was never a moment when the din of battle would not have drowned out any attempt at conversation between the two ships, and while it is quite probable that the Admiral made the remark, it is doubtful if he shouted it to the Brooklyn.” Be that as it may, the admiral’s action suited the words. The battle now witnessed the remarkable sight of the Hartford and her lashed consort, Metacomet, leading the column of ships directly across the minefield.

Among the papers found after his death, Farragut had written in a memorandum, “Allowing the Brooklyn to go ahead was a great error. It lost not only the Tecumseh, but many valuable lives, by keeping us under the guns of the fort for thirty minutes.”

Farragut Rushes Into Mine-Infested Water

Rushing westward of Brooklyn was a bold and courageous decision to make, but it paid off handsomely, because no ship in his formation struck a mine, or at least none exploded. “Some of us,” one sailor said, “expected every moment to feel the shock of an explosion … and to find ourselves in the water.” Mines could be heard bumping against the ships’ copper bottoms, and several times the snapping of primers could be heard. But as Farragut had surmised, these particular mines had been so long under water that they were not effective.

By his firm and quick decision the momentum of running past the fort was not lost. From the moment of Hartford’s turn, her starboard battery, followed by those of Brooklyn and the ships behind, spat a torrent of flame, smoke, and flying iron at Fort Morgan, again driving the gunners to their bombproofs. The fleet poured in 491 projectiles but inflicted little damage—the elevation of the Yankee guns had been too high. At this moment, the Union ironclads which, in obedience to orders, had delayed before the fort, occupying its guns until the fleet had passed, drew near the rear wooden ships and opened up on Tennessee.

Having entered the lower bay, Hartford now appeared before the Tennessee, which steered to ram her, meanwhile firing shells at her that killed 10 men and wounded five. Yet, the slowness of the Confederate ironclad and the mobility of the sloop caused the attempted ramming to fail.

A Shot Tore Into the 8-Inch Gun, Killing its Captain

The Rebel gunboats, however, were hitting their enemies with a terribly accurate, methodical, and sustained barrage. From the Morgan the sloop Oneida received a shell in her starboard boiler, engulfing the engine room in scalding steam, cutting down the entire watch: eight men dead and 30 wounded. Topside, fragments tore off the captain’s arm, decapitated a marine, and critically wounded the men at the 9-inch gun. Another shot tore into the 8-inch gun, killing its captain and sponger; a third cut the wheel ropes and set fire to the deck above the forward magazine. Disabled, she had to be towed from the action. The Selma repeatedly pummeled the Hartford, whose decks, according to a marine on board, looked like a slaughter pen.

Indeed, it was in this phase of the battle that the Hartford and Metacomet lost more men and were most seriously damaged. But according to Captain Drayton, not a man faltered. “There might perhaps have been a little excuse,” he said, “when it is considered that a great part of four gun crews were at different times swept away … in every case the killed and wounded were quietly removed, the injuries at the guns made good, and in a few moments except for traces of blood nothing could lead me to suppose that anything out of the ordinary had happened.”

It was Hampton Roads all over again—where the small Confederate ships, protected by the Virginia, had inflicted severe blows on the Federal ships—or so it seemed. While the Tennessee, protected by her armor, exchanged shot and shell with the wooden ships, causing them heavy damage, she again tried in vain to ram the Brooklyn, and also the Richmond and the Lackawanna. But she was too slow, and the blows were avoided. “The ram received from us three full broadsides of nine-inch solid shot, each broadside being eleven guns,” said Captain Thornton Jenkins of the Richmond. “They were well-aimed and all struck.” When he examined the ram the next day, all he found were some scratches.

Meanwhile, the ironclad turned about, but her circle brought her under Fort Morgan, and in this fashion the Confederate gunboats were temporarily isolated. As successive pairs of the fleet crossed the minefield, and out of range of Fort Morgan, the light gunboats cast off their lashings and were sent in pursuit of their tormentors. In addition, the Gaines and Morgan, off Farragut’s starboard bow, received a withering fire from Hartford’s cannon.

Union Sailors Find the Confederates in Complete Disarray

With guns barking, Metacomet, Lt. Cmdr. James Jouett commanding, cast off from the flagship and dashed for the Selma, the Port Royal joining the chase to make the contest completely uneven. The Rebel gunboat attempted a prudent retreat up the bay, but was overhauled, punctured with shot and, hopelessly outclassed in every respect, surrendered. Boarding her, Union sailors found a complete mess. Fifteen men lay mangled and one lieutenant, his bowels ripped out, flapped over the breach of a cannon. When Lieutenant Patrick Murphey of Selma, his arm in a sling, came aboard to surrender, he drew up before his old friend and stiffly said, “Captain Jouett … the fortunes of war compel me to tender you my sword.” Jouett would have no part of such formality and replied, “Pat, don’t make such a damned fool of yourself. I have had a bottle on ice for you for the last half hour.”

The Gaines, hit in 17 places, her rudder disabled, and leaking badly, sought refuge near Fort Morgan and Tennessee, but foundered 400 yards short. The Morgan, momentarily grounded, freed herself and gained a position under the guns of Fort Morgan. Later, under cover of darkness, she escaped to fight another day. Likewise, the Tennessee contented herself to lie under the guns of Fort Morgan and fire at the approaching vessels. In this position, Farragut’s natural assumption was that Buchanan would either aid the fort to prevent a future exit of his fleet from the bay, or he would steam to sea and play havoc with the transports and light gunboats. In any case, the prevailing opinion of the fleet’s officers was that Ol’ Buck would seek no general action against the intruding Yankees away from the supporting guns of Fort Morgan.

The Hartford anchored about four miles northwest of Fort Morgan, due east from Fort Powell, at about 8:35, the rest of the fleet anchoring astern of her. When Farragut disengaged himself from his lashings and came down to the poop deck, Captain Drayton approached him, “What we have done has been well done, sir, but it all counts for nothing so long as the Tennessee is there under the guns of Fort Morgan.” The admiral agreed, ”I know it, and as soon as these people have had their breakfast, I am going for her.”

“Grim, Silent and Rigid”

Across the way, the hero of Hampton Roads, limping up and down the deck impatiently, pacing in perplexity, knew he had a decision to make. His ram had been inspected and found to be generally undamaged, but the Tennessee had been hit several times in the smokestacks, and the perforations had reduced her draft so that she could not attain anything like maximum speed. Still, she had not been built for speed anyhow, and as long as she could move at all, Admiral Buchanan was content. In this quiet interlude the men of the Tennessee also breakfasted on hardtack and coffee. Surgeon Conrad remembered “the men all eating standing, creeping out of the ports on the after decks to get fresh air,” and he described Ol’ Buck as “grim, silent and rigid.”

After some 15 minutes, Buchanan called out to the captain, “Follow them up, Mr. Johnston, we cannot simply let them go this way.” As the fact penetrated, and the surgeon heard muttered comments from every rank, he ventured to ask the question himself, “Are you going into that fleet, admiral?” Instantly came the reply, “I am, Sir!”

Turning toward another officer, Conrad whispered under his breath, “Well, we’ll never come out of there whole.” Afterward he learned the reason for this apparently suicidal decision. The Tennessee had only six hours of coal, and Buchanan meant to burn it fighting to the end. “He did not mean to be trapped like a rat in a hold, and made to surrender without a struggle.” As naval historian William M. Still, Jr., correctly supposes, Buchanan was counting on surprise (the enemy was at anchor) to inflict the maximum damage possible, then retreat again under the guns of Fort Morgan and act like a floating battery.

Farragut had been planning his own next move and had come to the conclusion that he would wait for dark, then board the Manhattan and personally lead the three Union monitors, exploiting their shallow draft and gigantic Dahlgrens, in attack against the Tennessee.

Ol’ Buck’s Gamble

Buchanan saved him the trouble. For a few minutes a heavy rain squall passed over, and when pushed away by the wind, a call, at about 8:45, came down from aloft the flagship, “The ram is coming for us.” Farragut refused to believe it, thinking, “I did not think Ol’ Buck was such a fool.”

Conrad watched as “one after another of the big wooden frigates swept out in a wide circle.” With inferior speed and exposed tiller chains, Tennessee was not equipped for close-in fighting, and by attacking the whole Union squadron, Buchanan threw away his great defensive strengths.

According to Admiral Mahan, Buchanan should have exploited the light draft of his vessel, as well as the range of his Brooke rifles, by staying in shallow waters far from the Federal ships and battering them from afar. By attacking at close quarters, he was playing into Farragut’s hands. Mahan’s view makes sense. So how does one explain Buchanan’s decision to come to close quarters? First, if the Tennessee stayed in shallow waters, she could have stopped the three Union ironclads (whose draft was equal to or less than hers) from coming to close quarters. Second, from the whole battle, as well as from his report afterward, it is clear that Buchanan (thinking, perhaps, of his experience with the Virginia) trusted in the ram. This hope would prove his undoing. Experience had proven that a ship could not be rammed while in motion. Indeed, two years later at Lissa the Austrian ironclad Herzhborg Ferdinand Max would succeed in ramming the Italian Re d’Italia only after the latter, struck in the rudder, was lying still in the water.

11 Dead, 43 Wounded

When Farragut saw the Tennessee coming, he ordered all ships to steer for her at once, seizing the initiative and putting the Confederates on the defensive. The Brooklyn lunged first, firing steel-cored shot from her bow chasers. At the very last moment the Tennessee sheared off, giving her some heavy shots in passing. That ended the day for the Brooklyn, 11 dead and 43 wounded. Then the wooden ship Monongahela, with her consort Kennebec still lashed on her port side, separated from the circle of ships, and with a tower of white foam creaming from her iron prow, came running at full speed, “which we on board the Tennessee,” said Surgeon Conrad, “fully realized as the supreme moment of the test of our strength.”

The Monongahela struck the ironclad’s armored knuckle with tremendous but glancing impact, tearing away her own iron prow, shattering the butt ends of her planking. The shock threw most of the men in both ships to the deck. At the moment of impact, the Tennessee fired two shots that completely penetrated the hull and passed out the opposite side. The Monongahela responded with an impressive broadside that did no more damage than scrape the paint.

She was hardly away, reported the Tennessee’s Lieutenant Wharton, “when a hideous-looking monster came creeping up on our port side,” the monitor Manhattan, “whose slowly revolving turret revealed the cavernous depth of a mammoth gun. ‘Stand clear of the port side!’ I shouted. A moment after a thundering report shook us all, while a blast of dense, sulphurous smoke covered our port-holes, and 440 pounds of iron, impelled by 60 pounds of powder, admitted daylight through our side, where before it struck us there had been over two feet of solid wood, covered with five inches of solid iron … I was glad to find myself alive after that shot.”

The Tennessee vs. The Lackawanna

With hardly time to recover, the Tennessee now found herself the target of the sloop Lackawanna. Under a full head of steam, Lackawanna smashed at right angles into the after end of the ram’s casemate, crushing the wooden ship’s stem and causing a considerable leak. She struck with such force that the two vessels swung parallel head to stern, the Tennessee bringing two guns to bear on the Lackawanna, but the Union ship bearing only one. The bluejackets were close enough to hear the Rebels swearing at them, and from the Lackawanna were hurled a spittoon and a holystone to add to the shot and shell. The Tennessee sent two percussion shots that lit up the berth deck like a pinball machine, knocking down men by the bunch and setting fire to the magazine. This was answered with a shot that damaged Tennessee’s thinly protected tiller chains, jamming her steering gear to cause a lazy left turn. Another shot immobilized the after-port shutter. Buchanan sent for a repair party of firemen to clear it with sledgehammers. Two braced their backs against the casemate, holding the shutter bolt steady, while their mates slammed away.

“Suddenly,” said Surgeon Conrad, “there was a dull sounding impact, and at the same instant the men whose backs were against the shield were split in pieces. I saw their limbs and chests, severed and mangled, scattered about the deck, their hearts lying near their bodies.” Everyone including the admiral was “covered from head to foot with blood, flesh, and viscera.” Lost in the horror was Ol’ Buck, cut down by an iron splinter, alone in his agony. Conrad saw that one of Buchanan’s legs was twisted and crushed under his body. The medic diagnosed the wound as a compound fracture, and from every indication the leg would have to come off. Sending for the captain, in frightful pain Buchanan gasped, “Well, Johnston, they’ve got me. You’ll have to look out after her now. This is your fight, you know.”

Now the two flagships, Rebel and Yankee, warily approached each other bow to bow. Then the two ships rushed at one another in a struggle that became an awful, prolonged affair of violent give and take. The Hartford struck a glancing blow, which was further mitigated by her port anchor catching in the gunwale of the Tennessee. The flagship poured her whole port broadside into the ram, 980 pounds of smashing iron, but the solid shot merely dented the side and bounded harmlessly into the air. Incensed Yankee sailors fired revolvers into the enemy’s gun ports, one shot horribly mutilating the face of the chief engineer. The ram replied by sending a shell battering through Hartford’s berth deck and sick bay, killing eight. Locked in a death grip, the ships came port to port so close that an engineer on the Tennessee bayoneted a Union man on the Hartford, and a Union sailor put a pistol ball through the engineer’s shoulder at point-blank range.

“Can You Say ‘For God’s Sake’ by Signal?”

Farragut put his helm to starboard and circled to ram again, when the Lackawanna, misjudging the swiftly changing positions of a dozen vessels all converging on a single point, rammed the Hartford starboard aft, cutting a deep wound to within two feet of the waterline. For the moment, pandemonium reigned, some sailors believing the flagship was sliced through, and she might have been had the Lackawanna still carried her iron prow. Looking over the side, Farragut saw a few inches of plank above water and ordered Drayton to advance full speed at the enemy. Within a few moments of the order, the Lackawanna again loomed up on starboard.

The agitated admiral yelled to the army signal officer, Lieutenant Kinney, “Can you say ‘For God’s sake’ by signal?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then say to the Lackawanna, ‘For God’s sake, get out of our way and anchor!!’”

The Hartford steamed ahead. Surrounded on all sides, Tennessee became the target of the whole squadron. She had been rammed at least four times, but as her casemate construction was continued well below the waterline, the principal damage was suffered by the Union ships.

But the dauntless, if foolishly directed, Tennessee was in her death throes. The twin-turreted ironclads Chickasaw and Winnebago doggedly tormented her by placing themselves directly astern, “firing the two eleven-inch guns in their forward turret like pocket pistols.” The Tennessee’s armor began to crack. Then all the weak points of the ironclad began to fail; the port shutters, their chains shattered, blocked the portholes, making it impossible for gunners to fire. The rudder chains were smashed, making it impossible to steer.

With the Tennessee out of control, the Chickasaw was able to lie alongside, almost rail to rail, and begin hammering the casemate with all four of her guns. The funnel, knocked to pieces, caused steam pressure to fall to almost zero, and a suffocating smoke permeated the ironclad while the temperature in the engine room increased to 145 degrees. Incapable of steering, standing still, with water pouring in from leaks opened by repeated collisions with the enemy, the Tennessee was wholly disabled.

Confederates Solemnly Surrender

“Realizing our helpless condition,” convinced that the ship was “nothing more than a target,” Commander Johnston went below to inform Admiral Buchanan, who said with what must have been the bitterest gall, “If you cannot do further damage you had better surrender.” Johnston climbed to the hurricane deck, lowered the Confederate colors and, “decided with an almost bursting heart, to hoist the white flag.”

It was about 10 o’clock in the morning.

But the USS Ossipee was bearing down under a full head of steam, could not check herself in mid-career, and caromed into the helpless ram. Her skipper, Commander William LeRoy, a comrade from the old navy, hailed, “Hello, Johnston, how are you?” He sent a boat and Johnston came aboard, “I’m glad to see you, Johnston, here’s some ice water for you,” he said. They disappeared into his cabin to renew old times over a bottle.

For his part, Farragut acted properly, although not as generously as he might have. He did not go aboard the Tennessee to call on the wounded admiral, and demanded that a junior officer board the ram to take the admiral’s sword. This was the same sort of insult that years earlier had inspired the rage of his adoptive father, Captain David Porter, when a British junior officer tried the same during the surrender of his flagship at Valpariso Bay in the War of 1812, on which ship Farragut was then a midshipman. To the junior Confederate officers Farragut was polite, if distant; yet when the fleet surgeon visited Buchanan, who indicated no particular friendship for Farragut, the surgeon made it clear to Farragut that the admiral’s feelings had been hurt. General Page asked that Buchanan be sent under parole to Mobile, but Farragut refused.

After the battle, in writing to Secretary Welles, Farragut, a Southern man by birth and association, was far more gentle with Admiral Buchanan. But, he had a personal grudge against those officers who had been trained by the U.S. government, had supported that government, had been supported in turn by it, but had then turned in rebellion against it. He might have friends in the South, but personally his emotions were too involved to allow him to treat Buchanan as he might have.

Farragut also thanked the officers and men of the fleet, and mentioned that he “led” them into Mobile Bay. Captain Alden of the Brooklyn, who had been posted to lead the fleet in and who had nearly lost the battle for the Union, took offense at the admiral’s statement and went aboard the Hartford to protest. Farragut took the man below to his cabin, and what transpired there we know not, but ever afterward there was a coolness between the two men.

Casualties: 315 Killed and Wounded

Farragut had won a brilliant victory, but at what cost? Fifty-two officers and men had been killed and 170 wounded. Adding the losses of the Tecumseh, the number of killed increases to 145, and the total losses to 315 killed and wounded. Aside from the loss of an ironclad, the sloop Oneida had been disabled, the Hartford had been hit 20 times and the Brooklyn 59 times. Others had received serious damage except for the ironclads which, though they had been repeatedly hit (the Winnebago alone 19 times), had resisted well. A supply ship that tried to follow the fleet against orders was disabled by a shot from Fort Morgan, grounded, and later burned by the Confederates. The Southerners lost 12 killed and 20 wounded. Taken prisoner were 280, including Admiral Buchanan, whose leg would be saved. The Tennessee and Selma were captured, and the Gaines was gutted. Fort Morgan had only one killed and three wounded.

The press and the masses hailed Farragut as the greatest naval officer since Nelson. The dauntless manner in which he had damned the torpedoes and hurled the wooden prows of his cruisers against the iron-knuckled sides of the Tennessee brought praise from naval experts as well as from laymen. Admiral Mahan considered Mobile Bay the strongest evidence for Farragut’s audacity and naval genius, and wrote pages of praise on the tactical handling of the fleet, thus consciously or unconsciously obscuring the admitted fact that this battle was void of major strategic importance.

Rear Admiral Farragut Earns Well Deserved Accolades for Military Heroism

And perhaps it was just as well, for Farragut had not then, and has not yet, received full historical credit for his telling blows on the Mississippi River. President Lincoln considered the Southerner the best appointment made in either service. Secretary Welles wrote in his memoirs, “I considered him a great hero of the war.” Atlanta fell to Sherman on September 2, and combined with Farragut’s victory dramatically enhanced Lincoln’s prospects for reelection. Secretary of State William Seward came to the heart of the matter: “The victory at Atlanta comes in good time, as the victory in Mobile does, to vindicate the wisdom and energy of the war administration.”

Within a few hours after the surrender of the Tennessee (which was towed to New Orleans and pressed into Union service), the Chickasaw steamed westward and joined five gunboats in pummeling Fort Powell. The fort commander readily saw that his position was untenable and at about midnight the place was evacuated and blown up.

On Dauphin Island, the Federal army had not lagged. After a fierce exchange, Union batteries had silenced Fort Gaines and prevented the employment of its guns on the fleet. The fleet then joined Granger’s forces in the investment of the fort and, surrounded on three sides by the navy plus a fourth by the army, unfurled the white flag on August 7. General Page and his officers at Fort Morgan spat in the direction of Fort Gaines and cursed its commander, Charles DeWitt Anderson, for his half-hearted attempt to defend his position. General Page was not so easily dismayed. Workers, reservists, militia, two Louisiana artillery regiments, six companies of cavalry, and a battalion of convicts, 4,000 in all, girded themselves for the final assault.

The Confederate Army in Atlanta, fighting for its life against Sherman, ignored Mobile’s pleas. Only a handful of recruits responded to the call at Montgomery. The governor of Mississippi also was silent. Granger’s forces were transported to Mobile Point, and a siege train was brought from New Orleans. Farragut then stationed his ships, which now included the prize Tennessee, so that Fort Morgan was surrounded on land and sea. Determined to defend his post to the last extremity, the fiery 57-year-old Page responded to a request for surrender, “I am prepared to sacrifice life, and will only surrender when I have no means of defense.”

At daylight on August 22, a hundred Army and monitor guns opened a blistering, well-coordinated bombardment around the clock. The fort shook. The walls were breached in many places, its casemates crumbled, wooden buildings were set on fire, and all but two of its guns were knocked out. When a fire threatened the powder magazine around midnight, General Page had his entire powder supply wetted down. By daylight on August 23 he had taken enough, and he raised the white flag.

“We landed at Fort Morgan and went over the place,” reported journalist FitzGerald Ross. “I confess I did not like it at all. It is built in the old style…. When bricks fly about violently by tons’ weight at a time, which is the case when they come in contact with 15-inch shells, they make themselves very unpleasant to those who have trusted them for protection.”

The Problem of Mobile

Mobile was out of business. But the capture of the lower bay, and the complete closing of the port to blockade-runners, together with the absence of a major military movement in the hinterland that hinged upon the capture of Mobile, convinced Farragut that there was no point of immediately pressing up the bay and conducting a campaign against the city. In fact, he appears to have become a little cynical toward the whole war. “It [the city of Mobile] would be an elephant and take an army to hold it. And besides, all traitors and rascally speculators would flock to that city, and pour into the Confederacy the wealth of New York.”

As autumn wore on, Farragut’s subordinates began to worry about his health. He fainted while talking to Captain Perkins of the Chickasaw. Perkins attributed this to exhaustion, and the fact that “his health is not very good anyway.” Likewise, Captain Drayton of the Hartford began to become concerned over the admiral’s failing strength. In one of his letters home, Farragut himself seems to have concluded his days as a sea fighter were over. “This is the last of my work and I expect a little respite.” He sailed home from Pensacola at the end of November.

If adequate troops had accompanied Farragut’s naval force, the Union could have taken the city of Mobile after the surrender of the forts guarding the bay’s entrance, but the army felt it could not commit the necessary troops until early 1865. Eventually, a combined army and navy effort finally attacked and besieged the city in March and April of that year. Mobile surrendered on April 12th, three days after Appomattox, and four years to the day after the firing on Fort Sumter.

The Royal Navy could have broken the Union blockade and rescued the Confederacy within a month of an order being given.

History would have been very different in consequence.

In Britain, Palmerston was pro-Confederacy but the politically-conscious working classes and middle class were solidly pro-Union, taking the view that slavery was a sin against humanity.

And the British fleet would need a large naval base (city) on this side of the Atlantic.